Professional Documents

Culture Documents

On Dead Certainties

Uploaded by

scribd4tavo0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

35 views11 pagesHow do we preserve the integrity of the trial process when historians accept a relativist epistemology, says Reuel Schiller. According to Farber, historical relativism, post-modernism, multiculturalism, and critical legal studies are the four horsemen of the apocalypse, he says. Schiller: falsehoods, myths, and ideologically-biased narratives are more corrosive of the political and legal

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentHow do we preserve the integrity of the trial process when historians accept a relativist epistemology, says Reuel Schiller. According to Farber, historical relativism, post-modernism, multiculturalism, and critical legal studies are the four horsemen of the apocalypse, he says. Schiller: falsehoods, myths, and ideologically-biased narratives are more corrosive of the political and legal

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

35 views11 pagesOn Dead Certainties

Uploaded by

scribd4tavoHow do we preserve the integrity of the trial process when historians accept a relativist epistemology, says Reuel Schiller. According to Farber, historical relativism, post-modernism, multiculturalism, and critical legal studies are the four horsemen of the apocalypse, he says. Schiller: falsehoods, myths, and ideologically-biased narratives are more corrosive of the political and legal

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 11

Faculty Publications

UC Hastings College of the Law Library

Author: Reuel E. Schiller

Title: The Strawhorsemen of the Apocalypse: Relativism and the Historian as Expert

Witness

Source: Hastings Law Journal

Citation: 49 Hastings L.J. 1169 (1998).

Originally published in HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL. This article is reprinted with permission from

HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL and University of California, Hastings College of the Law.

Schiller Reuel

The Strawhorsemen of the Apocalypse:

Relativism and the Historian as Expert

Witness

by

REUEL E. SCHILLER*

What happens, Daniel Farber asks in his fascinating contribution

to this symposium, when expert witnesses belong to a discipline that

is no longer committed to objective notions of the truth? In particu-

lar, how do we preserve the integrity of the trial process when histo-

rians who are called upon to testify about historical facts accept a

relativist epistemology that allows them to manipulate the truth to

suit their ideological needs? According to Farber, historical relativ-

ism, post-modernism, multiculturalism, and critical legal studies have

emerged as the four horsemen of the apocalypse, forming an unholy

alliance that threatens to disrupt truth-finding in the judicial system.

The problem with Farber's paper is that these are not the four

horsemen of the apocalypse but rather the four strawhorsemen. Re-

ports of objectivity's demise, at least within the historical profession,

are premature. Furthermore, the nature of the trial process prevents

the abuses that Farber fears. By focusing his attack on these straw-

horsemen, Farber ignores a more serious threat to the integrity of the

past: falsehoods, myths, and ideologically-biased narratives mas-

querading as truths under the banner of objectivity. These are more

corrosive of the political and legal discourse than the intellectually

opaque theories about the subjective nature of truth that trouble

Farber.

Since Peter Novick's That Noble Dream was published in 1988,

there has been much talk among historians about how our profession

* Assistant Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of the

Law. B.A., Yale College; J.D., University of Virginia; Ph.D. (history), University of Vir-

ginia. I would like to thank Jo Carrillo, Mark Lambert, Roger Park, Suzanne Robinson,

and Jane Williams for their comments and suggestions and Nissa Strottman for providing

research assistance.

[11691

HeinOnline -- 49 Hastings L.J. 1169 1997-1998

HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL

is awash in subjectivist history. Yet, finding a genuinely "subjectivist

historian" is rather like searching for a unicorn. After seven years in

graduate school and at least as many attending history conferences, I

have yet to meet a historian who claimed that his scholarship was

nothing more than fiction or that his "version" of the events he stud-

ied was not an attempt to ascertain the truth. The historical profes-

sion is, at its core, profoundly committed to a search for truth about

the past. Consider, for example, the story of David Abraham that

Farber briefly mentions.' Abraham was an untenured history profes-

sor who was driven out of the profession by two eminent historians.

Their indictment against Abraham was that his book about the rela-

tionship between big business and the rise of National Socialism in

Germany contained numerous factual errors. Though Abraham cor-

rected his errors and demonstrated that they did not affect the valid-

ity of his thesis, his detractors saw his sloppy archival research as

symptomatic of the willingness of leftist historians to put political

ideology above historical truths in their research. Even assuming this

was what Abraham intended to do, which I do not,

2

the story does

not indicate that believers in objective historical truth are under siege

in the profession. Quite the contrary. Abraham's detractors won

out. "Objectivity" was a potent weapon in their successful campaign

to drum him out of the profession.

Consider also the profession's response to Simon Schama's book

Dead Certainties. Schama decided that he would write a work of fic-

tion based on historical research he had done. He wished to specu-

late on the results of his research without the usual restrictions re-

garding proof and evidence imposed on historical monographs.

Despite his disclaimers,

3

the profession reacted to the book as if it

were poison. As Schama put it, he was "held guilty of committing a

fiction."

4

Dead Certainties, its detractors claimed, undermined objec-

1. See Daniel A. Farber, Adjudication of Things Past: Reflections on History as

Evidence, 49 HASTINGS L.J. 1009, 1026 (1998).

2. There is no evidence that Abraham was committed to any sort of relativist epis-

temology or that he purposely misreported facts in order to support an ideological

agenda. Indeed, many have accused his detractors of furthering their own ideological in-

terests-which seem to have been to rid the profession of Marxist historians-at the ex-

pense of historical truths about the fall of the Weimar Republic. See PETER NOVICK,

THAT NOBLE DREAM: THE "OBJECTIVITY QUESTION" AND THE AMERICAN

HISTORICAL PROFESSION 619 n.60 (1988).

3. SIMON SCHAMA, DEAD CERTAINTIES: (UNWARRANTED SPECULATIONS) 320

(1991).

4. Gordon Wood, Novel History, N.Y. REVIEW OF BOOKS, June 27, 1991, at 12 (re-

[Vol. 49

HeinOnline -- 49 Hastings L.J. 1170 1997-1998

STRAWHORSEMEN OF THE APOCALYPSE

tivity, made a farce of genuine scholarship, and weakened the pub-

lie's faith in historians.

5

Unlike Abraham, Schama had tenure as well

as a reputation that could weather the storm of criticism he received.

Abraham's and Schama's experiences hardly indicate that historians

are no longer committed to finding historical truths. Indeed, the exis-

tence of objective truth seems to be something that a historian can

question only at great peril.

Since the profession is committed to the pursuit of truth, where

do these accusations of subjectivity come from? Why do Farber and

other non-historians, as well as many historians, seem to fear that his-

tory departments are soon to be abolished, their faculties incorpo-

rated into fiction writing programs? I believe there are four answers.

to this question.

1. The Success of That Noble Dream

In That Noble Dream, Novick examines how American histori-

ans' beliefs about the existence of historical truths changed from the

late nineteenth century to the present. The book is well-written,

thoughtfully researched, and powerfully argued. It is also full of de-

lightful academic gossip. This combination of appealing attributes

guaranteed it a wide readership among historians. Accordingly, the

"objectivity

debate" received a very wide airing.

6

That Noble Dream

revealed, as does Farber's piece, that there are some scholars in the

profession who disparage the idea of searching for historical truths.'

This fact does not indicate how influential these ideas are or whether

they affect the work of a majority of practicing historians. However,

by exposing their existence and discussing their ideas seriously, No-

vick caused a negative reaction among historians concerned with the

reputation of their profession.' Suddenly, an "objectivity crisis" as-

viewing SIMON SCHAMA, DEAD CERTAINTIES (1991)).

5. See Wood, supra note 4; see also Linda Colley, Fabricating the Past, TIMES

LITERARY SUPP., June 14, 1991, at 5 (reviewing SIMON SCHAMA, DEAD CERTAINTIES

(1991)).

6. Novick's discussion of contemporary historians' movement away from objectivist

epistemologies is but a small part of his larger study of how American historians have

thought about truth since the late nineteenth century. I can only imagine Novick's con-

sternation that the last quarter of his book generated such controversy while the first

three quarters went essentially undiscussed.

7. See Novick, supra note 2, at 599-605.

8. Colley's review of DEAD CERTAINTIES demonstrates a notable fear for the dis-

cipline's reputation. See Colley, supra note 5.

Apr. 1998]

HeinOnline -- 49 Hastings L.J. 1171 1997-1998

sumed titanic proportions.

2. The Widespread Recognition that Getting at the Truth is

Difficult

While a vast majority of historians view their scholarship as a

search for truth, they also recognize that finding the truth can be

problematic. Subjectivity must be distinguished from healthy skepti-

cism. Farber quotes Novick: "The notion of objectivity promotes an

unreal and misleading distinction between historical accounts 'dis-

torted' by ideological assumptions and history free of these traits."

9

I'm not sure that this quote indicates an abandonment of objective

truth. Rather, it recognizes that the truth can be hard to discern.

Typical graduate training in history has an objective component

and a subjective component. The objective component consists of re-

searching and writing a dissertation-searching for a historical truth

in a particular area. The subjective component is historiography-

reading the works of historians and examining how they have

differing, sometimes opposing, interpretations of historical events.

Studying historiography also involves examining how the conscious

and subconscious biases of historians affect their work. The purpose

of this subjective component of graduate education is not to turn

graduate students into radical anti-foundationalists. Instead, it

teaches skepticism and critical reading skills. It teaches you to be

cautious of your own biases and to be suspicious of others'.

Uncovering the truth is not impossible, but it is very difficult.

Indeed, the debates going on at the trials that Farber recounts are

historiographical ones that, because of their stakes, have taken on an

acrimony that rarely arises in a seminar room. The existence of these

debates, or the fact that each side accuses the other of bias, is not a

denial of the existence of objective truth. It is just a dialogue (or

screaming match) among historians who are taught to be wary of

other people's biases.

3. Bringing in New Voices

While the success of Novick's book and the difficulty of the his-

torian's enterprise are two reasons why people have begun to doubt

9. See Daniel A. Farber, Adjudication of Things Past: Reflections on History as

Evidence, 49 HASTINGS L.J. 1009, 1025 (1998) (quoting NOVICK, supra note 2, at 6).

HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 49

HeinOnline -- 49 Hastings L.J. 1172 1997-1998

STRAWHORSEMEN OF THE APOCALYPSE

the profession's commitment to objectivity, alone they are not a suf-

ficient explanation. Both phenomena are too parochial in nature to

affect the public's perception of what historians do. Instead, the

public's image of historians has been more dramatically affected by

changes in the types of history that scholars are interested in and the

political consequences of these changes. Starting in the early 1960s,

historians began bringing new voices into historical narratives." The

existing narratives were devoid of poor people, women, African-

Americans, and other racial and ethnic minorities. By studying these

groups, historians sought to complete these narratives by adding ac-

tors to the drama. This trend towards expanding the scope of the his-

torical inquiry was an attempt to produce a more objective historical

narrative-a complete history rather than a partial one.

As part of this enterprise, many historians sought to understand

the people they were studying by examining how they perceived

events. Thus, the history they wrote was perspectival in that it ex-

plored how certain groups interpreted the world around them: what

slaves thought about being enslaved, what immigrants thought about

the process of immigration and assimilation, what southern whites

thought about the trial of the Scottsboro Boys." This was getting at

the truth, but a different truth than more traditional history sought

out. These historians wished to learn the truth about people's beliefs

and impressions, not the truth about some external event. They

wished to know, for example, whether southern whites thought the

Scottsboro Boys were guilty, not whether they actually were.

Certain segments of the public reacted negatively to this new

type of historical inquiry. By bringing in new voices, it undermined

many of America's most cherished myths. Was America a melting

pot or a place where immigrants were coercively assimilated? What

was a Native American to make of Manifest Destiny? Were the rail-

roads miracles of modern technology that brought the United States

limitless prosperity or dangerous machines that mangled human

limbs and disrupted traditional economic relationships? Historians

who explore these questions are engaged in the process of truth

seeking. Yet they are accused of revisionism, political correctness,

10. This story has been told many times, most recently by Joyce Appleby in her

presidential address to the American Historical Association. See Joyce Appleby, The

Power of History, 103 AMER. HIST. REV. 1, 4-5 (1998).

11. See EUGENE D. GENOVESE, ROLL, JORDAN, ROLL: THE WORLD THE SLAVES

MADE (1974); Gary Gerstle, Liberty, Coercion, and the Making of Americans, 84 J. AM.

HIST. 524 (1997); JAMES E. GOODMAN, STORIES OF ScOTrSBORO (1995).

Apr. 1998]

HeinOnline -- 49 Hastings L.J. 1173 1997-1998

HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL

and subjectivity.

2

The sad fact is that many Americans have no de-

sire to learn a historical truth if it contradicts a preconception that

they hold about the past.

3

Accordingly, they berate historians who

seek out these uncomfortable truths and explore the perceptions of

people who have existed outside of the mainstream of American his-

tory. The tactic they frequently use is an accusation of subjectivity.

Historians are not seeking the truth but are instead out to hide it,

driven by an ideological desire to write "victims' history" and dispar-

age our nation. In fact, the truth is often hard to take, and the pro-

fession has paid the price, in accusations of subjectivity, for aggres-

sively seeking it.

12. See GARY B. NASH, CHARLOTTE CRABTREE, AND Ross E. DUNN, HISTORY ON

TRIAL: CULTURE WARS AND THE TEACHING OF THE PAST (1997). These accusations

are part of the huge literature about "political correctness" in the American academy.

The grandpere of this genre is Dinesh D'Souza's quasi-factual ILLIBERAL EDUCATION:

THE POLITICS OF RACE AND SEX ON CAMPUS (1991). For critiques noting D'Souza's

tendency to play fast and loose with facts see JOHN K. WILSON, THE MYTH OF

POLITICAL CORRECTNESS: THE CONSERVATIVE ATTACK ON HIGHER EDUCATION 69-

72 (1995); John Weiner, What Happened at Harvard, in BEYOND P.C. TOWARDS A

POLITICS OF UNDERSTANDING 97-106 (Patricia Auferheide ed., 1992). Even a sympa-

thetic reviewer of ILLIBERAL EDUCATION admitted that "the book turned out to contain

some serious and irresponsible factual errors." C. Vann Woodward, Freedom and the

Universities, in BEYOND P.C. TOWARDS A POLITICS OF UNDERSTANDING, supra. at 27.

D'Souza attacks multi-culturalism in ILLIBERAL EDUCATION, supra, at 59-93. For other

examples of accusations of political correctness, subjectivity, and revisionism aimed at

those who would expand the historical or literary canon, see MARTIN ANDERSON,

IMPOSTORS IN THE TEMPLE 145-57 (1992); ROGER KIMBALL, TENURED RADICALS:

How POLITICS HAS CORRUPTED HIGHER EDUCATION 27-33, 63-75, 166-89 (1990):

ALLAN BLOOM, THE CLOSING OF THE AMERICAN MIND 356-82 (particularly 366 n.17)

(1987); Thomas Short, "Diversity" and "Breaking the Disciplines": Two New Assaults on

the Curriculum, in ARE YOU POLITICALLY CORRECT? DEBATING AMERICA'S

CULTURAL STANDARDS 91-117 (Francis J. Beckwith & Michael E. Bauman eds., 1993)

[hereinafter POLITICALLY CORRECT]; Irving Howe, The Vahte of the Canon, in

POLITICALLY CORRECT, supra, at 133, 133-46; Allan Bloom, Western Civ--and Me: An

Adress at Harvard University, in POLITICALLY CORRECT, supra, at 147, 147-61; John R.

Searle, Is There a Crisis in American Higher Education?, in OUR COUNTRY, OUR

CULTURE: THE POLITICS OF POLITICAL CORRECTNESS (Edith Kurzweil & William Phil-

lips eds., 1994) at 227, 227-43; David Sidorsky, Multiculturalism and the University, in

OUR COUNTRY, OUR CULTURE, supra, at 244,244-57.

13. The controversy surrounding the Enola Gay exhibition at the Smithsonian is a

good, if profoundly depressing, example of this phenomena. See History and the Public:

What Can We Handle? A Round Table About History After the Enola Gay Controversy.

82 J. AM. HIST. 1029-1144 (1995).

[Vol. 49

HeinOnline -- 49 Hastings L.J. 1174 1997-1998

STRAWHORSEMEN OF THE APOCALYPSE

4. Historians in the Courtroom

The final factor that has contributed to this image of a subjectiv-

ist historical profession was a series of encounters between the legal

system and historians. Indeed, it is these incidents-the Sears sex

discrimination case, the Webster brief, the Colorado gay rights

case-that seem to give Farber the most concern. If historians are

not committed to seeking objective truths, then how can they claim to

be experts? Farber is worried that they have become nothing more

than advocates who use their authority as historians to hide the fact

that they are willing to make up whatever facts they need because

they do not believe that an objective truth exists.

Farber's concern is misplaced. Surely "Law Office History" or,

as one historian has eloquently put it, "the illicit relationship between

Clio and the Court,"'

4

existed long before the rise of relativist episte-

mologies. As long as advocates exist, so will warped history. Con-

sider Justice Taney's opinion in Dred Scot

t 5

or Justice Black's dissent

in Adamson v. California.

1 6

Each is an example of the misuse of his-

tory-or perhaps I should say the use of fake history-to justify a

particular outcome. Yet nobody would accuse Taney or Black of

being epistemological relativists.

In addition to this age-old temptation to mold history to suit the

needs of litigants, the nature of the historian's search for truth-even

when such a search is completely bona fide-often does not mesh

well with the needs of the legal profession. When Alice Kessler-

Harris wrote about her experience testifying for the plaintiffs in the

Sears trial, she did not write about the need to shape her testimony to

the needs of the EEOC.

7

Instead, she wrote about her intense frus-

tration with a trial process that did not allow her to explain the com-

plexities of the evolution of gendered conceptions of work.'

8

A trial

often demands more than a historian can offer. It asks for definitive

answers when a historian may prefer to give cautious, conditional an-

14. Alfred H. Kelly, Clio and the Court: An Illicit Love Affair, 1965 SuP. Cr. REV.

119.

15. Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1857).

16. Adamson v. California, 332 U.S. 46, 69-92 (1947) (Black, J., dissenting).

17. As Kessler-Harris pointed out, she would not have been asked to testify if her

findings were incompatible with the position of the plaintiffs. Alice Kessler-Harris, Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission v. Sears, Roebuck and Company: A Personal Ac-

count, 35 RADICAL HIST. REv. 57, 63 (1986).

18. See id. at 72-75.

1175

Apr. 1998]

HeinOnline -- 49 Hastings L.J. 1175 1997-1998

swers. The law needs black and white, while historians often deal in

shades of gray. The currents of historical causation are multifaceted,

profoundly complicated, and often contradictory. Yet a trial has no

time for these subtleties. Indeed, discussing them leaves oneself open

to attack on cross-examination. As Kessler-Harris wrote:

Testimony had a double-edged quality. In this case, once given and

written, it had a life of its own, at the mercy of cross-examining

lawyers, and not subject to qualification. Because it constituted the

boundaries within which examination could happen, it had to en-

compass the totality of my expertise: broad enough to meet the

needs of the plaintiff, and yet sufficiently restrained as to offer few

loopholes that the defendants could use to undermine it. What sort

of claims to truth could be justified by such expertise?

9

Perhaps the problem is not that historians no longer believe in the

existence of historical truth, but instead that a trial is not always the

best way to discover it.

There is no doubt that historians came out of the trials that Far-

ber recounts looking bad. Furthermore, there is no excuse for the

behavior of the historians who seek to silence others who uncover

ideologically inconvenient truths. Yet, despite inflamed passions on

the part of the historians, the lesson I draw from these cases is that

the adversarial process is an excellent buffer against those who would

abuse historical truths in the interests of their client. Through the use

of rival experts and impeaching cross-examination, lawyers put histo-

rians' testimony through a crucible that uncovers biases, flawed data,

laughable interpretations, and outright deceit. That unicorn-like

creature, the relativist historian, who blatantly shapes the facts to suit

the needs of his client, may warp young minds in the classroom, but

he will be challenged and discredited in the courtroom. While histo-

rians debate the merits of Derridian relativism in their ivory tower,

the legal process is safe.

Farber ends his paper by stressing the potentially liberating na-

ture of historical inquiry. Objective truth, not historical relativism, is

the ally of democracy and the enemy of totalitarianism.

2

' I whole-

19. 1d. at 74.

20. It seems to me that, contrary to the stories that Farber recounts, it is usually the

right that is coercing the left into silence. See JOHN K. WILSON, THE MYTH OF

POLITICAL CORRECTNESS 31-63 (1995); James Boyle, The P.C. Harangue, 45 STAN. L.

REV. 1457-60 (1993). Also, consider the story of David Abraham, supra note 2.

21. The association of post-modernism with fascism is a common trope in the writ-

ings of those who attack relativist epistemologies. To the extent that post-modern

HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 49

HeinOnline -- 49 Hastings L.J. 1176 1997-1998

STRAWHORSEMEN OF THE APOCALYPSE

heartedly agree with Farber. So I was forced to ask myself why por-

tions of his paper irked me so. Ultimately, I am disturbed by the ten-

dency of both liberal and conservative critics to make mountains of

relativist fascism from molehills of postmodem leftism. Where is the

inquiry about the other side in this so-called "culture war"? Who is

John Finnis and why does he seem to show up in a surprising number

of legal cases involving historical testimony, always on the same, con-

servative side? What about Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, another fre-

quent foot soldier in the culture wars, whose lapsed left-wing creden-

tials make her an attractive talking head for those opposed to the

"excesses of political correctness"?

What about the hundreds of

other scholars, funded by the Olin Foundation or the Heritage Foun-

dation, whose scholarship-surprise, surprise-supports a particular,

conservative world View?' Trendy, left-wing relativism makes such

an easy target that we seem to have forgotten about the other side.

Farber's article presents the "problem" of instrumentalist schol-

arship as if it is only a phenomenon of the left. Perhaps the real

problem is that only the left attempts to rationalize its assaults on the

truth with zany epistemological models, more easily ridiculed than

understood. The right undertakes its campaign of misinformation

under the banner of objectivity, thereby hiding its biases. These

right-wing assaults on historical truths are more potent than those

propagated'by the left-leaning academics who, quite candidly, most

Americans had not heard of until Dinesh D'Sousa and Rush Lim-

baugh exposed their alleged depredations. Indeed, the right's abuses

of the truth are committed by those with a wide audience and a great

deal more media savvy, economic support, and political clout than

Peter Novick, Hayden White, or Gary Peller. Is it not time we dis-

cussed them? Let us not stay trapped in an ivory tower where liber-

als and leftists attack each other over issues of objectivity while the

rest of society listens to a well-financed and uncontested stream of

historical half-truths.

thought owes as much to Deweyan pragmatism as it does to Heiddeger or Paul De Man

this connection is mystifying. See generally RICHARD RORTY, PHILOSOPHY AND THE

MIRROR OF NATURE (1979); RICHARD RORTY, THE CONSEQUENCES OF PRAGMATISM

(1982); RICHARD RORTY, CONTINGENCY, IRONY, AND SOLIDARITY (1989). This guilt

by association is like dismissing modem American poetry as totalitarian because of the

importance of Ezra Pound within the canon.

22. See JEAN STEFANIC AND RICHARD DELGADO, NO MERCY: How

CONSERVATIVE THINK TANKS AND FOUNDATIONS CHANGED AMERICA'S SOCIAL

AGENDA passim (1996); see also Wilson, supra note 20, at 26-30; Boyle, supra note 20, at

1460.

Apr. 1998]

HeinOnline -- 49 Hastings L.J. 1177 1997-1998

HeinOnline -- 49 Hastings L.J. 1178 1997-1998

You might also like

- Historical Truth and Lies About the Past: Reflections on Dewey, Dreyfus, de Man, and ReaganFrom EverandHistorical Truth and Lies About the Past: Reflections on Dewey, Dreyfus, de Man, and ReaganRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (2)

- Wilson 1998Document15 pagesWilson 1998Fatimat SanusiNo ratings yet

- Slavery: A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual LifeFrom EverandSlavery: A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual LifeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (9)

- What Is History?: History Describes Carr's Book As "Still Unsurpassed As A Stimulating and Provocative Statement by ADocument6 pagesWhat Is History?: History Describes Carr's Book As "Still Unsurpassed As A Stimulating and Provocative Statement by AAdil Mehtab100% (1)

- Unsolved History: Investigating Mysteries of the PastFrom EverandUnsolved History: Investigating Mysteries of the PastRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Holachek 2010 The Berlin-Carr DebateDocument131 pagesHolachek 2010 The Berlin-Carr DebatejerweberNo ratings yet

- Historical Narrative and Truth in The BibleDocument16 pagesHistorical Narrative and Truth in The BibleFenixbrNo ratings yet

- Hoax: Hitler's Diaries, Lincoln's Assassins, and Other Famous FraudsFrom EverandHoax: Hitler's Diaries, Lincoln's Assassins, and Other Famous FraudsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Reviews in History - What Is History - 2012-03-08Document8 pagesReviews in History - What Is History - 2012-03-08Arka ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Reframing Rhetorical History: Cases, Theories, and MethodologiesFrom EverandReframing Rhetorical History: Cases, Theories, and MethodologiesNo ratings yet

- SEC AssignmentDocument5 pagesSEC AssignmentbitchNo ratings yet

- Is Historical Knowledge Neutral or PositionedDocument9 pagesIs Historical Knowledge Neutral or PositionedSritamaNo ratings yet

- Old Historians, New Historians, No Historians: The Derailed Debate on the Genesis of IsraelFrom EverandOld Historians, New Historians, No Historians: The Derailed Debate on the Genesis of IsraelNo ratings yet

- Historia HistoriaDocument83 pagesHistoria HistoriaPdro Huamn ZuritaNo ratings yet

- People of Plenty: Economic Abundance and the American CharacterFrom EverandPeople of Plenty: Economic Abundance and the American CharacterRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- To What Extent Does History Combine Fact and Fiction EssayDocument6 pagesTo What Extent Does History Combine Fact and Fiction Essaytoddie2609No ratings yet

- The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom: A comprehensive historyFrom EverandThe Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom: A comprehensive historyNo ratings yet

- History As Moral ReflectionDocument12 pagesHistory As Moral ReflectionaydogankNo ratings yet

- 1 Millard. Story, History, TheologyDocument28 pages1 Millard. Story, History, TheologyCordova Llacsahuache LeifNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of War: A Study of Its Role in Early SocietiesFrom EverandThe Evolution of War: A Study of Its Role in Early SocietiesRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Historical ImaginationDocument10 pagesHistorical ImaginationFernandaPiresGurgelNo ratings yet

- Apocalypse against Empire: Theologies of Resistance in Early JudaismFrom EverandApocalypse against Empire: Theologies of Resistance in Early JudaismRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Pseudo-Archaeology as State Supported IdeologyDocument17 pagesPseudo-Archaeology as State Supported Ideologymaltigre0% (1)

- Defending William Miller-The Midnight CryDocument241 pagesDefending William Miller-The Midnight CrySeventhnoticeNo ratings yet

- The Hand of History: An Anthology of Quotes and CommentariesFrom EverandThe Hand of History: An Anthology of Quotes and CommentariesNo ratings yet

- Stolen Generations Testimony: Trauma, Historiography, and The Question of Truth'Document16 pagesStolen Generations Testimony: Trauma, Historiography, and The Question of Truth'HermanNo ratings yet

- The Secret of Three Bullets: How New Nuclear Weapons Are Back on BattlefieldsFrom EverandThe Secret of Three Bullets: How New Nuclear Weapons Are Back on BattlefieldsNo ratings yet

- Was The Civil War Inevitable EssaysDocument4 pagesWas The Civil War Inevitable Essaysafibavcbdyeqsx100% (2)

- Descent Into Discourse: The Reification of Language and the Writing of Social HistoryFrom EverandDescent Into Discourse: The Reification of Language and the Writing of Social HistoryNo ratings yet

- Revisionism RevisitedDocument8 pagesRevisionism RevisitedJackie LiangNo ratings yet

- Epistemologiado ArmárioDocument262 pagesEpistemologiado ArmárioBeano de BorbujasNo ratings yet

- Isaiah 40-55 as an Anti-Babylonian PolemicDocument16 pagesIsaiah 40-55 as an Anti-Babylonian PolemicShristirajenNo ratings yet

- Excerpt From 'These Truths'Document5 pagesExcerpt From 'These Truths'OnPointRadio50% (2)

- Pseudohistory: Distorting the Historical RecordDocument7 pagesPseudohistory: Distorting the Historical RecordSorinNo ratings yet

- Raymond P Ojserkis Beginnings of the ColDocument76 pagesRaymond P Ojserkis Beginnings of the Colspena5923No ratings yet

- A Beautiful Argument About War Paul MonkDocument7 pagesA Beautiful Argument About War Paul MonkJacek RomanowNo ratings yet

- ANE Mythography and The BibleDocument31 pagesANE Mythography and The BibleYoussefNo ratings yet

- Quests MerkleyDocument15 pagesQuests Merkleymilkymilky9876No ratings yet

- SWT Critical BibliographyDocument12 pagesSWT Critical Bibliographyapi-609705702No ratings yet

- Anbalakan. Objectivity in History. An Analysis.Document13 pagesAnbalakan. Objectivity in History. An Analysis.Jorge Cano MorenoNo ratings yet

- Books in Summary: Germans and The Holocaust at The Beginning of 1996, Few Historians Expected A New HisDocument4 pagesBooks in Summary: Germans and The Holocaust at The Beginning of 1996, Few Historians Expected A New HisBogdan-Alexandru JiteaNo ratings yet

- Berlin 2001Document13 pagesBerlin 2001ToNo ratings yet

- Genesis of World Wa 00 HarrDocument796 pagesGenesis of World Wa 00 Harrafonsoarch9232No ratings yet

- University of Pennsylvania PressDocument12 pagesUniversity of Pennsylvania PressNelson DubonNo ratings yet

- Peter Gay - Freud For HistoriansDocument273 pagesPeter Gay - Freud For HistoriansRenato Moscateli100% (9)

- Critical Review of Peter Novick's 'That Noble DreamDocument9 pagesCritical Review of Peter Novick's 'That Noble DreamEsteban ZapataNo ratings yet

- Plotting The Sixties 297136Document208 pagesPlotting The Sixties 297136Lobo Solitario100% (1)

- Cambridge University Press, British Association For American Studies Journal of American StudiesDocument23 pagesCambridge University Press, British Association For American Studies Journal of American StudiesvalesoldaNo ratings yet

- Works and Lives, The Anthropologist As Author, C. Geertz (1988)Document164 pagesWorks and Lives, The Anthropologist As Author, C. Geertz (1988)EskimOasis100% (2)

- Truth and ObjectivityDocument23 pagesTruth and ObjectivityRadja GorahaNo ratings yet

- Jesus and his Cast of ArchetypesDocument22 pagesJesus and his Cast of Archetypesbuster301168No ratings yet

- Witz and Rassool - Making HistoriesDocument10 pagesWitz and Rassool - Making HistoriesEclipse_83No ratings yet

- CRITIQUEPAPERDocument5 pagesCRITIQUEPAPERNeil B. Matu-ogNo ratings yet

- Sedgwick Eve Kosofsky Epistemology Closet PDFDocument262 pagesSedgwick Eve Kosofsky Epistemology Closet PDFpriteegandhanaik_377No ratings yet

- Political Studies As Narrative and Science, 1880-2000Document24 pagesPolitical Studies As Narrative and Science, 1880-2000RafaelSerraNo ratings yet

- Neumann - Diplomacy in Star TreckDocument22 pagesNeumann - Diplomacy in Star TreckJoezac DecastroNo ratings yet

- Noise Industrial ProcessDocument8 pagesNoise Industrial Processscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Fractals DiffusionDocument11 pagesFractals Diffusionscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Noise Industrial ProcessDocument8 pagesNoise Industrial Processscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- New Complex Solutions To The Nonlinear Electrical Transmission Line ModelDocument8 pagesNew Complex Solutions To The Nonlinear Electrical Transmission Line Modelscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Chiltosan TelmisartanDocument7 pagesChiltosan Telmisartanscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- WNT B Catenin Pathway in Human Fibrioman-Like DiseasesDocument14 pagesWNT B Catenin Pathway in Human Fibrioman-Like Diseasesscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Prediction and Parametric Optimization of SurfaceDocument9 pagesPrediction and Parametric Optimization of Surfacescribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Vacuum EvolutionDocument10 pagesVacuum Evolutionscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Information Technology Telecommunications and Information ExchangeDocument48 pagesInformation Technology Telecommunications and Information Exchangescribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Absortion SpectometryDocument6 pagesAbsortion Spectometryscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Second Harmonic Imaging of Plasmonic Pancharatnam Phase MetasurfacesDocument10 pagesSecond Harmonic Imaging of Plasmonic Pancharatnam Phase Metasurfacesscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Multiagent Based AlgorithmDocument6 pagesMultiagent Based Algorithmscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Diffraction Modeling PDFDocument6 pagesDiffraction Modeling PDFscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Darkfield Colors From Multi-Periodic Arrays of Gap Plasmon ResonatorsDocument13 pagesDarkfield Colors From Multi-Periodic Arrays of Gap Plasmon Resonatorsscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Experiential Learning in Soil SciencesDocument5 pagesExperiential Learning in Soil Sciencesscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Homeomorphisms of Hashimoto TopologiesDocument10 pagesHomeomorphisms of Hashimoto Topologiesscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Modal Gain Analysis of Transverse Bragg ResonanceDocument7 pagesModal Gain Analysis of Transverse Bragg Resonancescribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Early Determinants of DevelopmentDocument7 pagesEarly Determinants of Developmentscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Coalbed MethaneDocument10 pagesCoalbed Methanescribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Thermodynamics Properties of A Regular Black HoleDocument11 pagesThermodynamics Properties of A Regular Black Holescribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Transport and Structure in Semimetallic PolymersDocument8 pagesTransport and Structure in Semimetallic Polymersscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Engineers As Problem-Solvers PDFDocument7 pagesEngineers As Problem-Solvers PDFscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Brain DevelopmentDocument13 pagesBrain Developmentscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Spin Interaction Under The Collision of Two-Kerr (-Anti) de Sitter Black HolesDocument17 pagesSpin Interaction Under The Collision of Two-Kerr (-Anti) de Sitter Black Holesscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Efficient Charging of SupercapacitorsDocument11 pagesEfficient Charging of Supercapacitorsscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Riesssman Narrative AnalysisDocument8 pagesRiesssman Narrative AnalysispmjcsNo ratings yet

- The Theory and Practice of Welfare PartershipDocument20 pagesThe Theory and Practice of Welfare Partershipscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Fibroblast Growth Factor 9 Regulation by microRNASDocument22 pagesFibroblast Growth Factor 9 Regulation by microRNASscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Identification of Criteria and Indicators For Sustainable Community Forest ManagementDocument64 pagesIdentification of Criteria and Indicators For Sustainable Community Forest Managementscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- HaitiDocument36 pagesHaitiscribd4tavoNo ratings yet

- Social Psychology 12th Edition Myers Test BankDocument28 pagesSocial Psychology 12th Edition Myers Test Bankcoreymoorenemxdfgiwr100% (11)

- Introduction To Philippine History and Its SourcesDocument16 pagesIntroduction To Philippine History and Its SourcesChindie DomingoNo ratings yet

- Essay 3 LetterDocument3 pagesEssay 3 Letterapi-577077653No ratings yet

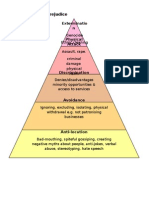

- Allports Scale of PrejudiceDocument1 pageAllports Scale of PrejudicebmckNo ratings yet

- Write Effective Demand LetterDocument26 pagesWrite Effective Demand Letteramazing_pinoy100% (5)

- Toward Understanding Understanding: The Importance of Feeling Understood in RelationshipsDocument22 pagesToward Understanding Understanding: The Importance of Feeling Understood in RelationshipsevelyneNo ratings yet

- Types of Bias in Psychometric Test TranslationDocument4 pagesTypes of Bias in Psychometric Test Translationposonona100% (1)

- Halo Effect and Related StudiesDocument3 pagesHalo Effect and Related StudiesKumarSatyamurthyNo ratings yet

- Crisis Response Task Force Final Report: President's Council On Diversity, Inclusion, and RespectDocument16 pagesCrisis Response Task Force Final Report: President's Council On Diversity, Inclusion, and RespectinforumdocsNo ratings yet

- Palaroan Theorypaper1Document7 pagesPalaroan Theorypaper1api-438185399No ratings yet

- Grade-11-Philo - Q1 Mod 2 Method of Philospphizing v3Document26 pagesGrade-11-Philo - Q1 Mod 2 Method of Philospphizing v3Lani Bernardo Cuadra83% (93)

- What Not Taught in SchoolDocument7 pagesWhat Not Taught in Schoolbukester1No ratings yet

- The Complexity of Multiparty Negotiations: Wading Into The MuckDocument9 pagesThe Complexity of Multiparty Negotiations: Wading Into The MuckIvan PetrovNo ratings yet

- Reason and Impartiality As Requirements For EthicsDocument11 pagesReason and Impartiality As Requirements For EthicsSkyNayvieNo ratings yet

- Berger, Kellermann - 1994 - Acquiring Social InformationDocument41 pagesBerger, Kellermann - 1994 - Acquiring Social InformationAvimar Junior100% (1)

- A Taxonomy and Treatment of Uncertainty For Ecology and Conservation BiologyDocument11 pagesA Taxonomy and Treatment of Uncertainty For Ecology and Conservation BiologyJorge LopRomNo ratings yet

- Design, User Experience, and Usability: Marcelo M. Soares Elizabeth Rosenzweig Aaron MarcusDocument500 pagesDesign, User Experience, and Usability: Marcelo M. Soares Elizabeth Rosenzweig Aaron MarcusJosé Carlos Gamero LeónNo ratings yet

- RoB 2.0 Guidance Parallel TrialDocument68 pagesRoB 2.0 Guidance Parallel TrialOscar PonceNo ratings yet

- Analyze Intention of Words or Expressions Used in Propaganda TechniquesDocument5 pagesAnalyze Intention of Words or Expressions Used in Propaganda TechniquesChristian Joseph HerreraNo ratings yet

- The Code Contains Six CanonsDocument30 pagesThe Code Contains Six CanonsRaymond Vera Cruz VillarinNo ratings yet

- Boutique Build Australia: Code of EthicsDocument4 pagesBoutique Build Australia: Code of EthicsSam Patel100% (1)

- Donald T. Campbell - Methods For The Experimenting Society - 1Document38 pagesDonald T. Campbell - Methods For The Experimenting Society - 1Pablo Menese CamargoNo ratings yet

- Case Study On AI in Finance SectorDocument4 pagesCase Study On AI in Finance Sectortejas pawarNo ratings yet

- EXAMINING AUTHORIAL BIASESDocument13 pagesEXAMINING AUTHORIAL BIASESAna Mae DusaranNo ratings yet

- August 9, 2010 INTENDED APPELLANT's Submission Used To Successfully Argue For Leave To Appeal. The Court of Appeal of N.B. File Number 82/10/CA ANDRE MURRAY v. BETTY ROSE DANIELSKIDocument105 pagesAugust 9, 2010 INTENDED APPELLANT's Submission Used To Successfully Argue For Leave To Appeal. The Court of Appeal of N.B. File Number 82/10/CA ANDRE MURRAY v. BETTY ROSE DANIELSKIJustice Done Dirt CheapNo ratings yet

- Racial Literacy - Final Lessons Grade 7Document31 pagesRacial Literacy - Final Lessons Grade 7pandrenNo ratings yet

- Methodological DiscussionDocument11 pagesMethodological DiscussionMihaela DIACONUNo ratings yet

- Barriers To CommunicationDocument7 pagesBarriers To CommunicationkhanNo ratings yet

- Systematic Error (Bias) : Types of Bias Non-Response Bias Healthy Worker Effect Berkson BiasDocument4 pagesSystematic Error (Bias) : Types of Bias Non-Response Bias Healthy Worker Effect Berkson BiasMarion SanchezNo ratings yet

- English 8-Q3-M1Document17 pagesEnglish 8-Q3-M1Eldon JulaoNo ratings yet

- The Ugly History of Beautiful Things: Essays on Desire and ConsumptionFrom EverandThe Ugly History of Beautiful Things: Essays on Desire and ConsumptionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (7)

- The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionFrom EverandThe Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (811)

- They Thought They Were Free: The Germans, 1933-45From EverandThey Thought They Were Free: The Germans, 1933-45Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (159)

- Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of TerroristsFrom EverandTalking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood, and the (Un)Making of TerroristsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- First Steps: How Upright Walking Made Us HumanFrom EverandFirst Steps: How Upright Walking Made Us HumanRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- The Age of Wood: Our Most Useful Material and the Construction of CivilizationFrom EverandThe Age of Wood: Our Most Useful Material and the Construction of CivilizationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (95)

- Generations: The Real Differences between Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, Boomers, and Silents—and What They Mean for America's FutureFrom EverandGenerations: The Real Differences between Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, Boomers, and Silents—and What They Mean for America's FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (43)

- The Best Strangers in the World: Stories from a Life Spent ListeningFrom EverandThe Best Strangers in the World: Stories from a Life Spent ListeningRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (31)

- The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and LoveFrom EverandThe Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and LoveRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (383)

- Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat: Why It's So Hard to Think Straight About AnimalsFrom EverandSome We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat: Why It's So Hard to Think Straight About AnimalsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (85)

- The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist RuinsFrom EverandThe Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist RuinsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (139)

- Play: How it Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the SoulFrom EverandPlay: How it Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the SoulRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (96)

- The Book of Yokai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese FolkloreFrom EverandThe Book of Yokai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese FolkloreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (40)

- Sea People: The Puzzle of PolynesiaFrom EverandSea People: The Puzzle of PolynesiaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (210)

- Eight Bears: Mythic Past and Imperiled FutureFrom EverandEight Bears: Mythic Past and Imperiled FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human SocietiesFrom EverandGuns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human SocietiesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (642)

- The Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017From EverandThe Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (43)

- The Wheel of Time: The Shamans of Mexico Their Thoughts about Life Death and the UniverseFrom EverandThe Wheel of Time: The Shamans of Mexico Their Thoughts about Life Death and the UniverseRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (81)

- The Web of Meaning: Integrating Science and Traditional Wisdom to Find our Place in the UniverseFrom EverandThe Web of Meaning: Integrating Science and Traditional Wisdom to Find our Place in the UniverseRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (12)

- The Status Game: On Human Life and How to Play ItFrom EverandThe Status Game: On Human Life and How to Play ItRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- A Pocket History of Human Evolution: How We Became SapiensFrom EverandA Pocket History of Human Evolution: How We Became SapiensRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (71)

- The Geography of Genius: A Search for the World's Most Creative Places from Ancient Athens to Silicon ValleyFrom EverandThe Geography of Genius: A Search for the World's Most Creative Places from Ancient Athens to Silicon ValleyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (65)

- Life: The Leading Edge of Evolutionary Biology, Genetics, Anthropology, and Environmental ScienceFrom EverandLife: The Leading Edge of Evolutionary Biology, Genetics, Anthropology, and Environmental ScienceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (34)

- The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell StoriesFrom EverandThe Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (115)

- The Hidden Life of Life: A Walk through the Reaches of TimeFrom EverandThe Hidden Life of Life: A Walk through the Reaches of TimeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)