Professional Documents

Culture Documents

AG Herring Response To Virginia Stay Request

Uploaded by

jsnow489Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

AG Herring Response To Virginia Stay Request

Uploaded by

jsnow489Copyright:

Available Formats

No.

14A196

__________________________________________________________________

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

_____________

MICHLE B. MCQUIGG, IN HER OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS PRINCE WILLIAM

COUNTY CLERK OF CIRCUIT COURT, PETITIONER,

V.

TIMOTHY B. BOSTIC, ET AL., RESPONDENTS.

_____________

ON APPLICATION TO STAY THE MANDATE OF

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

_____________

MEMORANDUM BY STATE REGISTRAR JANET M. RAINEY

IN SUPPORT OF STAYING THE MANDATE AND REQUESTING

THAT THE MOTION TO STAY BE TREATED AS A CROSS-PETITION

FOR CERTIORARI IN RAINEY v. BOSTIC, No. 14-153

_____________

Mark R. Herring

Attorney General of Virginia

Trevor S. Cox

Deputy Solicitor General

Stuart A. Raphael

Solicitor General

Counsel of Record

OFFICE OF THE

VIRGINIA ATTORNEY GENERAL

900 East Main Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

(804) 786-7240

sraphael@oag.state.va.us

August 18, 2014

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................................................................................... iii

INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1

ARGUMENT .................................................................................................................................. 1

I. The traditional factors warrant a stay...................................................................................1

A. There is a reasonable probability the Court will grant certiorari. ........................2

B. The outcome is sufficiently in question to satisfy the fair prospect

standard. ...................................................................................................................2

C. Irreparable harm is threatened regardless of whether a stay is issued, but

the balance of hardship favors a stay. ......................................................................8

II. The Court should treat McQuiggs motion to stay as a cross-petition for certiorari

in Rainey v. Bostic, No. 14-153, and grant both petitions. ................................................12

CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................. 13

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ..................................................................................................... 14

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases

Bd. of Ed. v. Super. Court of Ca.,

448 U.S. 1343 (1980) .................................................................................................................. 2

Bishop v. Smith,

Nos. 14-5003 & 14-5006, 2014 U.S. App. LEXIS 13733 (10th Cir. J uly 18, 2014) .................. 7

Bowers v. Hardwick,

478 U.S. 186 (1986) ................................................................................................................ 3, 4

Conkright v. Frommert,

556 U.S. 1401 (2009) .............................................................................................................. 2, 8

DeBoer v. Snyder,

No. 14-1341, 2014 U.S. App. LEXIS 7259 (6th Cir. Mar. 25, 2014) ......................................... 7

Elrod v. Burns,

427 U.S. 347 (1976) .................................................................................................................... 8

Evans v. Utah,

No. 14-4060 (10th Cir. J uly 11, 2014) (ECF No. 01019277937) ............................................... 7

Herbert v. Evans,

No. 14A65, 2014 WL 3557112 (U.S. J uly 18, 2014) ................................................................. 7

Herbert v. Kitchen,

134 S. Ct. 893 (2014) .................................................................................................................. 6

Herbert v. Kitchen,

No. 14-124 (U.S. docketed Aug. 5, 2014) ................................................................................... 6

Hollingsworth v. Perry,

133 S. Ct. 2652 (2013) ................................................................................................................ 2

Hollingsworth v. Perry,

558 U.S. 183 (2010) .................................................................................................................... 1

Kitchen v. Herbert,

961 F. Supp. 2d 1181 (D. Utah 2013) ................................................................................... 5, 10

Latta v. Otter,

No. 14-35420 (9th Cir. May 20, 2014) (ECF No. 11) ................................................................ 7

Lawrence v. Texas,

539 U.S. 558 (2003) ................................................................................................................ 3, 4

Loving v. Virginia,

388 U.S. 1 (1967) ........................................................................................................................ 3

Maryland v. King,

133 S. Ct. 1 (2012) .................................................................................................................. 2, 8

iv

Michael H. v. Gerald D.,

491 U.S. 110 (1989) .................................................................................................................... 3

New Motor Vehicle Bd. of Cal. v. Orrin W. Fox Co.,

434 U.S. 1345 (1977) .................................................................................................................. 8

Nken v. Holder,

556 U.S. 418 (2009) .................................................................................................................. 12

Nken v. Mukasey,

555 U.S. 1042 (2008) ................................................................................................................ 12

Planned Parenthood of Se. Pa. v. Casey,

505 U.S. 833 (1992) .................................................................................................................... 3

Romer v. Evans,

517 U.S. 620 (1996) ................................................................................................................ 3, 4

Rostker v. Goldberg,

448 U.S. 1306 (1980) .................................................................................................................. 8

Turner v. Safley,

482 U.S. 78 (1987) ...................................................................................................................... 3

United States v. Windsor,

133 S. Ct. 2675 (2013) .................................................................................................. 3, 4, 5, 10

Zablocki v. Redhail,

434 U.S. 374 (1978) .................................................................................................................... 3

Statutes

Va. Code Ann. 64.2-200 (2012)................................................................................................. 10

Va. Code Ann. 64.2-307 (2012)................................................................................................. 11

Other Authorities

BLAG Merits Br., United States v. Windsor,

133 S. Ct. 2675 (2013) (No. 12-307) ......................................................................................... 4

David Ingram,

Obama administration recognizes Utah same-sex marriages, Reuters (J an. 10, 2014) ............. 6

Gates Amicus Br.,

Bostic v. Schaefer, 2014 WL 3702493 (4th Cir. J uly 28, 2014) (No. 14-1167) (ECF 169-1) .. 10

Marissa Lang,

Same-sex couples shatter marriage records in Utah, The Salt-Lake Tribune (Dec. 26, 2013) .. 6

Petn for Certiorari, Rainey v. Bostic,

No. 14-153 (U.S. docketed Aug. 12, 2014) ........................................................................ passim

State Defs. Br. on Future Proceedings,

Fisher-Borne v. Smith, No. 1:12-CV-589 (M.D.N.C. Aug. 13, 2014) (ECF No. 104) ............ 11

Stephen M. Shapiro, et al.,

Supreme Court Practice (10th ed. 2013) ................................................................................... 12

v

U.S. Census Bureau,

State & County Quick Facts, at http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/index.html ............................ 9

WAVY News, Video: Tony London, Tim Bostic talk about gay marriage case

(4 p.m. ed., Aug. 14, 2014) ..........................................................................................................9

1

INTRODUCTION

Shortly after taking office in J anuary 2014, Virginia Attorney General Mark R. Herring

advised the district court that (1) he had determined that Virginias same-sex-marriage ban violates

the Fourteenth Amendment, but (2) State Registrar J anet M. Rainey would continue to enforce the

ban until a definitive judicial ruling can be obtained. The Attorney General concluded that this

approach is faithful to his oath to support the Constitution of the United States, and consistent with

the obligation of the Executive Branch of the Virginia State government to enforce the ban while

its validity is adjudicated. See Petn for Certiorari at 6-7, 203a-212a, Rainey v. Bostic, No. 14-153

(U.S. docketed Aug. 12, 2014) (App. A). Although it is painful to keep Virginias same-sex

couples and their children waiting any longer to enjoy the rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment, the rule of law requires that this Court be afforded the time needed to settle the

question. Irreparable harm is threatened whichever way the Court decides the stay request,

although determining if the harm is irreparable depends on whether Virginias ban is

unconstitutional. Under these circumstances, the balance of hardships favors a stay. The

unintended consequences and injury to third parties if this Court were to permit the district courts

injunction to take effect prematurely and later uphold Virginias ban are greater than the injury to

the named plaintiffs if the stay is granted but the ban is later invalidated. Either way, however, the

most responsible course of action is to decide the constitutionality of Virginias ban as quickly as

possible. Accordingly, the Court should grant the stay, treat the stay application as a cross-petition

for certiorari in No. 14-153, and grant both petitions at the Courts earliest opportunity.

ARGUMENT

I. The traditional factors warrant a stay.

The Court follows familiar standards, Hollingsworth v. Perry, 558 U.S. 183, 190 (2010)

(per curiam), in determining whether to stay a lower courts mandate pending petition for

2

certiorari. To warrant that relief, [the movant] must demonstrate (1) a reasonable probability

that this Court will grant certiorari, (2) a fair prospect that the Court will then reverse the

decision below, and (3) a likelihood that irreparable harm [will] result from the denial of a stay.

Maryland v. King, 133 S. Ct. 1, 2 (2012) (Roberts, C.J ., in chambers) (quoting Conkright v.

Frommert, 556 U.S. 1401, 1402 (2009) (Ginsburg, J ., in chambers)).

A. There is a reasonable probability the Court will grant certiorari.

As set forth in Raineys petition for certiorari, this case raises an exceptionally important

question on which the Court granted certiorari in Hollingsworth v. Perry, 133 S. Ct. 2652, 2661

(2013), but was unable to decide because the petitioners there lacked standing, id. at 2667-68.

Rainey Petn for Certiorari at 14-19 (App. A). It is also a question on which State and federal

courts are divided. The Fourth and Tenth Circuits have held that same-sex-marriage bans violate

the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses; the Eighth Circuit, and the highest courts of several

States, have held the opposite. Id. at 20-21. Lower courts are also divided on whether heightened

scrutiny applies to laws that discriminate against gay people, and on whether same-sex-marriage

bans constitute gender classifications that, for that reason alone, warrant heightened scrutiny. Id.

at 25-33. These factors make it reasonably probable that the Court will grant certiorari to resolve

the split on the question presented. King, 133 S. Ct. at 3.

B. The outcome is sufficiently in question to satisfy the fair prospect standard.

The fair-prospect-of-reversal consideration is more difficult. The Circuit J ustice must try

to predict the probable outcome of the case if certiorari were granted, which requires some skill

in the reading of tea leaves as well as in the process of legal reasoning. Bd. of Ed. v. Super. Court

of Ca., 448 U.S. 1343, 1347 (1980) (Rehnquist, J ., in chambers). Although Rainey agrees with the

Bostic and Harris respondents that the Fourth Circuits ruling was correct, sufficient uncertainty

lurks in the Courts tea leaves to satisfy the fair prospect standard.

3

To be sure, there is good reason to think that a majority of this Court will hold that State

same-sex-marriage bans violate the Fourteenth Amendment. Two lines of precedent converge on

that result. The first involves cases holding that marriage is of fundamental importance for all

individuals. Zablocki v. Redhail, 434 U.S. 374, 384 (1978). The Court has not limited the right

of marriage to the context in which it was historically exercised. That is why the Fourteenth

Amendment bars Virginia from banning interracial marriage, Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, 12

(1967), despite that interracial marriage was illegal in most States when the Fourteenth

Amendment was adopted, Planned Parenthood of Se. Pa. v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833, 847-48 (1992).

The fundamental right in question here is the right to marriage, not the right to marry as it was

historically practiced. If the rule were otherwise, there would be no right to interracial marriage;

no right of people owing child support to marry, Zablocki, 434 U.S. at 388-91; and no right of

prison inmates to marry, Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78, 94-99 (1987). Casey, in fact, specifically

rejected the narrowest-historical-context theory that J ustice Scalia once proposed as a limitation on

fundamental-rights analysis. See 505 U.S. at 847-48 (disavowing Michael H. v. Gerald D., 491

U.S. 110, 127-28, n.6 (1989) (opinion of Scalia, J .)). See also Rainey Petn for Certiorari at 22-25

(App. A).

The second line of precedent in this historical convergence has rejected efforts by the

government to discriminate against gay people. United States v. Windsor, 133 S. Ct. 2675, 2696

(2013); Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558, 573-74 (2003), overruling Bowers v. Hardwick, 478

U.S. 186 (1986); Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620, 632-36 (1996). Although those cases did not

resolve the level of scrutiny that applies to such laws, the Court found no legitimate governmental

interest sufficient to uphold any of the laws in question. Indeed, the justifications offered to save

3 of the Defense of Marriage Act in Windsorencouraging responsible procreation and

4

childrearing

1

and preserving traditional marriage

2

are the same justifications offered by J udge

Niemeyer and Clerk McQuigg in support of Virginias refusal to allow gay people to marry or to

recognize their marriages lawfully celebrated outside of Virginia. See McQuigg Mot. to Stay at

16-17. The majoritys decision in Windsor that no legitimate purpose supported DOMA seems

to require the same conclusion here. 133 S. Ct. at 2696. See Rainey Petn for Certiorari at 26-27

(App. A).

In attempting to predict how five J ustices will rule on this question, one cannot overlook

J ustice Scalias opinions; he has repeatedly predicted that this Courts decisions in Romer,

Lawrence, and Windsor will require the Court to strike down State laws banning same-sex

marriage. Colorados constitutional ban on anti-discrimination laws protecting gay people, which

the Romer majority found inexplicable by anything but animus toward the class it affects, 517

U.S. at 632, were defended at the time on the ground that Bowers permitted States to criminalize

homosexual conduct; if the States could do that, the argument went, surely it is constitutionally

permissible for a State to enact other laws merely disfavoring homosexual conduct, 517 U.S. at

641 (Scalia, J ., dissenting). In other words, Coloradans [were] . . . entitled to be hostile toward

homosexual conduct. Id. at 644 (Scalia, J ., dissenting). When Lawrence overruled Bowers and

held that the Constitution protects the intimate choices of gay people, J ustice Scalia said that the

opinion dismantle[d] the structure of constitutional law that has permitted a distinction to be made

between heterosexual and homosexual unions, insofar as formal recognition in marriage is

concerned. 539 U.S. at 604 (Scalia, J ., dissenting). And when Windsor held that the federal

government could not refuse to recognize same-sex marriages that were validly entered into in

1

BLAG Merits Br. at 11, United States v. Windsor, 133 S. Ct. 2675 (2013) (No. 12-307) (quoting

H.R. Rep. No. 104-664, at 12, 13 (1996)).

2

Id. at 10, 46.

5

another jurisdiction, J ustice Scalia said that the view that this Court will take of state prohibition

of same-sex marriage is indicated beyond mistaking by todays opinion . . . . How easy it is,

indeed how inevitable, to reach the same conclusion with regard to state laws denying same-sex

couples marital status. 133 S. Ct. at 2709 (Scalia, J ., dissenting).

Despite those predictions, however, the legal question here remains fraught with

uncertainty. The majority in Windsor expressly declined to address the question presented in this

case, id. at 2696, a point the Chief J ustice took pains to underscore. Id. at 2697 (Roberts, C.J .,

dissenting). And J ustice Alito, joined by J ustice Thomas, wrote in dissent that the Constitution

does not choose among what he called two viable views of marriage: one that he termed the

traditional or conjugal view, and the newer view that he termed the consent-based vision

of marriage. Id. at 2718. J ustice Alito found the Constitutions silence on that question enough

to end the matter as far as the judiciary is concerned, id., and he would not presume to enshrine

either vision of marriage in our constitutional jurisprudence, id. at 2719. So it appears from the

dissents in Windsor that at least three J ustices are receptive to the arguments raised by J udge

Niemeyer in the court of appeals, arguments capably taken up by Clerk McQuigg in this Court.

That the Court views the controversial question posed here as an open one is also

buttressed by reasonable inferences drawn from the fact that the Court has twice stayed lower court

rulings that would have allowed same-sex marriages to proceed in Utah before this Court could

have the final say. The Court issued no opinion either time and no J ustice dissented. It is difficult

to conceive of a rational explanation for those stays that would square with refusing to stay the

Fourth Circuits mandate here.

On December 20, 2013, a district court struck down Utahs same-sex-marriage ban and

enjoined its enforcement. Kitchen v. Herbert, 961 F. Supp. 2d 1181, 1216 (D. Utah 2013)

6

(Kitchen I). Both the district court and the Tenth Circuit declined to stay the injunction pending

appeal. On Utahs emergency motion, the Court stayed the injunction on J anuary 6, 2014, pending

disposition of Utahs appeal to the Tenth Circuit. Herbert v. Kitchen, 134 S. Ct. 893 (2014)

(Kitchen II).

In the week that followed the district courts ruling, local clerks issued more than 900

marriage licenses to same-sex couples.

3

During the 17-day window in which marriage licenses

were issued, approximately 1,400 gay couples got married in Utah.

4

Four of those newlywed couples then filed suit to require Utah to recognize their marriages.

On May 19, 2014, the Utah district court issued a preliminary injunction ordering just that. Evans

v. Utah, No. 2:14-cv-55, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 69177, at *57 (D. Utah May 19, 2014). The

district court denied Utahs request to stay the injunction, although it allowed a temporary reprieve

for Utah to seek review in the Tenth Circuit. Id. at *50-51.

In the meantime, on J une 25, 2014, the Tenth Circuit issued its judgment in Kitchen,

affirming the district courts ruling striking down Utahs same-sex-marriage ban under the

Fourteenth Amendment. Kitchen v. Herbert, No. 13-4178, 2014 U.S. App. LEXIS 11935, at *97

(10th Cir. J une 25, 2014) (Kitchen III). Citing the Supreme Courts stay in Kitchen, the Tenth

Circuit stayed its mandate pending the disposition of any subsequently filed petition for certiorari.

Id. Utahs petition for certiorari is now pending. Herbert v. Kitchen, No. 14-124 (U.S. docketed

Aug. 5, 2014).

3

Marissa Lang, Same-sex couples shatter marriage records in Utah, The Salt-Lake Tribune (Dec.

26, 2013), at http://www.sltrib.com/sltrib/news/57310957-78/sex-county-marriages-

couples.html.csp.

4

David Ingram, Obama administration recognizes Utah same-sex marriages, Reuters (J an. 10,

2014), at http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/01/10/us-usa-gaymarriage-utah-justice-

idUSBREA090WI20140110.

7

Having decided that Utahs marriage ban was unconstitutional, the Tenth Circuit, on J uly

11, 2014, denied Utahs request to stay the injunction in Evans, but permitted a ten-day window

for Utah to seek another stay from this Court. Evans v. Utah, No. 14-4060 (10th Cir. J uly 11,

2014) (ECF No. 01019277937). J udge Kelly would have issued the stay, explaining that the

panels haste complement[ed] the chaos begun by the district court in Kitchen and warning that

undoing what is about to be done will be labyrinthine. Id. at 2, 3 (Kelly, J ., concurring in part

and dissenting in part).

On J uly 18, 2014, this Court granted Utahs motion to stay the injunction in Evans pending

disposition of the appeal to the Tenth Circuit. Herbert v. Evans, No. 14A65, 2014 WL 3557112

(U.S. J uly 18, 2014). Given that the Tenth Circuit had already struck down Utahs marriage ban,

the stay in Evans makes sense only if this Court is reserving to itself the final decision on whether

the Constitution prohibits States from denying gay people the right to marry.

The Fourth Circuit below did not reconcile its refusal to stay the mandate with this Courts

stays in Kitchen and Evans; no reasonable distinction presents itself. Other circuits, by contrast,

have taken the cue. The Tenth Circuit panel that struck down Oklahomas ban, on the same day

the Court issued its stay in Evans, concluded sua sponte that a stay was appropriate pending the

disposition of petitions for certiorari. Bishop v. Smith, Nos. 14-5003 & 14-5006, 2014 U.S. App.

LEXIS 13733, at *71 (10th Cir. J uly 18, 2014) (citing Kitchen III). The Sixth Circuit similarly

stayed the injunction striking down Michigans same-sex-marriage ban, likewise finding this

Courts stay in Kitchen to be controlling. DeBoer v. Snyder, No. 14-1341, 2014 U.S. App. LEXIS

7259, at *4 (6th Cir. Mar. 25, 2014) (finding no apparent basis to distinguish Kitchen II). And

the Ninth Circuit likewise stayed the injunction striking down Idahos same-sex-marriage ban.

Latta v. Otter, No. 14-35420 (9th Cir. May 20, 2014) (ECF No. 11). J udge Hurwitz read this

8

Courts stay in Kitchen as having virtually instructed courts of appeals to grant stays in the

circumstances before us today. Id. at 3 (Hurwitz, J ., concurring).

In short, given the views expressed in Windsor by at least three J ustices, and in light of the

unmistakable signals from this Courts stays in Kitchen and Evans, the fair-prospect-of-reversal

consideration should be treated as satisfied here.

C. Irreparable harm is threatened regardless of whether a stay is issued, but the

balance of hardship favors a stay.

The irreparable-harm analysis is complicated here because whether a stay will cause

irreparable injury depends on how the Court decides the underlying legal question. If Virginias

same-sex-marriage ban violates the Fourteenth Amendmentwhether because it impinges upon a

fundamental right, fails strict or heightened scrutiny, or lacks a rational basisthe continued

withholding of Plaintiffs right to marry is irreparable. Cf. Elrod v. Burns, 427 U.S. 347, 373

(1976) (The loss of First Amendment freedoms, for even minimal periods of time, unquestionably

constitutes irreparable injury.). On the other hand, if the ban survives constitutional scrutiny, then

their constitutional rights have not been infringed and letting the injunction take effect would pose

a different kind of irreparable harm. [A]ny time a State is enjoined by a court from effectuating

statutes enacted by representatives of its people, it suffers a form of irreparable injury. King, 133

S. Ct. at 3 (quoting New Motor Vehicle Bd. of Cal. v. Orrin W. Fox Co., 434 U.S. 1345, 1351

(1977) (Rehnquist, J ., in chambers)).

Because irreparable injury is threatened either way, it is appropriate to balance the

equitiesto explore the relative harms to applicant and respondent, as well as the interests of the

public at large. Conkright v. Frommert, 556 U.S. 1401, 1401 (2009) (Ginsburg, J ., in chambers)

(quoting Rostker v. Goldberg, 448 U.S. 1306, 1308 (1980) (Brennan, J ., in chambers)) (internal

quotation marks omitted). That balance favors staying the mandate.

9

The Plaintiffs here are two couplesTimothy Bostic and Tony London, and Carol Schall

and Mary Townley. Bostic and London have lived together for 25 years and wish to marry; Schall

and Townley wish to have their California marriage recognized so Schall can adopt Townleys

sixteen-year-old biological daughter, and so Schall and Townley can both be listed as parents on

their daughters birth certificate. Rainey Petn for Certiorari at 5-6 (App. A).

If the injunction takes effect, it is unlikely that Bostic and London will rush to take

advantage of it by marrying right away, or that Schall and Townley will quickly move for Schall to

adopt their daughter. These well-represented couples, no doubt, are attuned to the risk that doing

that could moot this case before they have finished the important work they started. In fact, on

August 14, 2014, one day after the Fourth Circuit declined to stay the mandate, Bostic and London

appeared on their local television station and announced that they do not intend to marry right

away. Bostic said weve waited 25 years for this, so waiting another six months so we can do it

right is not that big of an issue for us. WAVY News, Video: Tony London, Tim Bostic talk about

gay marriage case, at 1:33 (4 p.m. ed., Aug. 14, 2014), at http://wavy.com/2014/08/14/video-tony-

london-tim-bostic-talk-about-gay-marriage-case/.

By contrast, it would be a very big issue for the Commonwealth and third parties who

must rely on presumptively valid marriages. For starters, Virginia will likely see many more

same-sex marriages than the 1,400 performed in Utah in the 17-day window in Kitchen. Virginias

population is 2.8 times as large as Utahs (8.2 million compared to 2.9 million).

5

If this Court

denies the stay, marriages will be performed during a period extending far longer than 17 days.

And if the Court ultimately were to uphold Virginias ban, the hundreds or thousands of marriages

taking place in the interim would be rendered doubtful.

5

See U.S. Census Bureau, State & County Quick Facts, at

http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/index.html.

10

It would be one thing if the burden fell only on those same-sex couples willing to assume

the legal risk of having their marriage invalidated. But it would not. Not only might their

marriages have to be unwound, but all of the legal relationships and transactions of third parties

who pass through their orbit would have to be untangled.

Children would be at greatest risk for having their lives disrupted. Morethan 2,500 same-

sex couples in Virginia are raising more than 4,000 children younger than age 18.

6

The biological

children of one spouse who are adopted by the other parent (as Schall wishes to do) could well

have to be un-adopted. And same-sex spouses who adopt children together could face having their

adoptions dissolved. Such scenarios are not fanciful. One of the same-sex couples in Evans, who

had previously wed in the District of Columbia, commenced adoption proceedings in Utah just

days after the ruling in Kitchen I, seeking to have the non-biological parent adopt the couples

four-year-old son. 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 69177, at *9. To be sure, Virginias same-sex-marriage

ban already denigrates the children of same-sex couples. It deprives them of the incalculable

benefit and security of having two legal parents and makes it more difficult for the children to

understand the integrity and closeness of their own family and its concord with other families in

their community and in their daily lives. Windsor, 133 S. Ct. at 2694. But permitting these

children to be adopted, only to have the State say it was just kidding, would heap another gross

indignity upon them.

Countless other third parties will be affected by an un-stayed ruling that is later reversed.

Employers and insurers who pay benefits to the same-sex spouse of an employee or of an insured

might have to seek restitution or, alternatively, might lack any remedy to recover the value of

benefits paid. A same-sex spouse whose partner dies intestate would have a superior claim to the

6

Br. of Amicus Curiae Gary J . Gates in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellees and Intervenors at 5,

Bostic v. Schaefer, 2014 WL 3702493 (4th Cir. J uly 28, 2014) (No. 14-1167) (ECF 169-1).

11

estate, but if this Courts ruling invalidated the marriage, the statutory heirs could contest the

spouses inheritance. See Va. Code Ann. 64.2-200 (2012) (governing descent of property

passing by intestate succession). The spouses right to remain in the family residence pending

settlement of the estate would likewise be jeopardized. Id. 64.2-307 (2012). And the Virginia

Department of Taxation would likely have to rescind tax returns filed by same-sex couples,

married filing jointly, and require the parties to file separate returns and to pay any resulting

deficiencies.

Virginia will not be the only State affected. A decision allowing the injunction to take

effect in this case will signal lower federal courts to follow suitthe opposite signal sent by the

stays in Kitchen and Evans. The Attorney General of North Carolina has already informed a

federal district court that North Carolinas same-sex-marriage ban is indistinguishable from

Virginias under the circuit precedent established in this case.

7

And circuit courts hearing cases in

the Fifth, Sixth, Seventh and Ninth Circuits, see Rainey Petn for Certiorari at 15-17 & nn. 7-17

(collecting cases) (App. A), likely would not stay any forthcoming rulings striking down same-sex-

marriage bans if this Court signaled that such stays are now unnecessary.

By no means would refusing to stay the mandate spell disaster. If this Court ultimately

were to rule that same-sex-marriage bans are unconstitutional, permitting marriage equality in the

interim would be like speeding without a seatbelt; if no accident occurs, the passengers will be just

fine. Some will be quite thrilled; others may feel nervous. But if this Courts decision should go

the other way, same-sex couples, their children, and innumerable third parties who interact with

them risk being thrown from the car. The status quo ante could not be restored, and putting the

pieces back together would pose a wrenching and insurmountable task.

7

State Defs. Br. on Future Proceedings at 4, Fisher-Borne v. Smith, No. 1:12-CV-589 (M.D.N.C.

Aug. 13, 2014) (ECF No. 104).

12

The Attorney General of Virginia has concluded that Virginias ban is unconstitutional and

that a majority of this Court is likely to strike it down. But the responsible course is to maintain

the status quo until this Court can definitively decide the question. It takes time to decide a case

on appeal. Sometimes a little; sometimes a lot . . . . A stay does not make time stand still, but does

hold a ruling in abeyance to allow an appellate court the time necessary to review it. Nken v.

Holder, 556 U.S. 418, 421 (2009).

II. The Court should treat McQuiggs motion to stay as a cross-petition for certiorari in

Rainey v. Bostic, No. 14-153, and grant both petitions.

Although this Court cannot make time stand still, it should recognize that time is of the

essence. In urging the Court to grant certiorari in No. 14-153, Raineys petition for certiorari asks

how much longer must these citizens and their children wait to realize the promise of equal

justice under law? Rainey Petn for Certiorari at 39 (App. A). Given the huge stakes involved

and the threat of irreparable harm regardless of how the stay question is decided, the Court should

reach and decide the merits as quickly as the rule of law will permit.

The Court may treat an application [for a stay] as a petition for certiorari and grant the

petition, either at the suggestion of the party or on its own motion. Stephen M. Shapiro et al.,

Supreme Court Practice ch. 17.9, at 891 (10th ed. 2013) (collecting cases). The Court did that in

Nken v. Mukasey, 555 U.S. 1042 (2008), when an alien who fled persecution in Cameroon faced

deportation. It should do that here as well, to resolve as quickly as possible what many view as the

most important civil rights issue of our time.

McQuiggs motion to stay the mandate lays out the same deep division among lower courts

that Rainey described in her own petition for certiorari. Rainey disagrees with McQuigg about

how the question presented should be answered. But they agree that this Court alone can provide a

definitive answer, and that it should grant certiorari to do that. There is no need to require

13

McQuigg to file a cross-petition for certiorari when her stay motion serves the same purpose.

With the completion of briefing on this motion, the table is set and the necessary participants are

present. And as shown in Raineys petition for certiorari, this case is the ideal vehicle to resolve

the controversy. Rainey Petn for Certiorari at 33-38 (App. A).

CONCLUSION

The Court should stay the mandate of the court of appeals, treat the stay application as a

cross-petition for certiorari in No. 14-153, and grant both petitions at its earliest opportunity.

Respectfully submitted,

By: /s/ Stuart A. Raphael

Stuart A. Raphael

Solicitor General of Virginia

Office of the Attorney General

900 East Main Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

(804) 786-7240 Telephone

(804) 371-0200 Facsimile

sraphael@oag.state.va.us

Mark R. Herring

Attorney General of Virginia

Trevor S. Cox

Deputy Solicitor General

E-mail: tcox@oag.state.va.us

14

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that on August 18, 2014, a copy of this paper was served by e-mail and U.S. mail

on the following counsel:

Counsel for Petitioner Michle McQuigg:

Byron J . Babione

Counsel of Record

David A. Cortman

David Austin R. Nimocks

J ames A. Campbell

Kenneth J . Connelly

Kellie M. Fiedorek

J . Caleb Dalton

ALLIANCE DEFENDING FREEDOM

15100 North 90th Street

Scottsdale, AZ 85260

bbabione@alliancedefendingfreedom.org

Counsel for Respondent Joanne Harris,

et al.:

J ames D. Esseks

J oshua A. Block

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

FOUNDATION

125 Broad Street, 18th Floor

New York, New York 10004

jesseks@aclu.org

jblock@aclu.org

Counsel for Respondent George E. Schaefer, III:

David B. Oakley

J effrey F. Brooke

POOLE MAHONEY P.C.

860 Greenbrier Circle, Suite 401

Chesapeake, VA 23320

doakley@poolemahoney.com

jbrooke@poolemahoney.com

Counsel for Respondents Timothy Bostic, et al.:

Theodore B. Olson

Matthew D. McGill

Amir C. Tayrani

Chantale Fiebig

Gibson Dunn & Crutcher LLP

1050 Connecticut Avenue, NW

Washington, DC 20036

tolson@gibsondunn.com

By: /s/ Stuart A. Raphael

Stuart A. Raphael

You might also like

- SB50 - Fix To Indiana's RFRADocument3 pagesSB50 - Fix To Indiana's RFRAEric HallNo ratings yet

- DOJ EEOC ComplaintDocument21 pagesDOJ EEOC ComplaintSusan SvrlugaNo ratings yet

- EO 45 DiscriminationDocument2 pagesEO 45 DiscriminationHelen BennettNo ratings yet

- DOJ Amicus Brief On Gay MarriageDocument46 pagesDOJ Amicus Brief On Gay MarriageRyan J. Reilly100% (1)

- 8:14-cv-00356 #54 - Nebraska Memo and OrderDocument34 pages8:14-cv-00356 #54 - Nebraska Memo and OrderEquality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- Tyler Clementi Higher Education Anti-Harassment Act of 2015Document10 pagesTyler Clementi Higher Education Anti-Harassment Act of 2015jsnow489No ratings yet

- 14-556 167 Members of The House of Representatives and 44 US SenatorsDocument60 pages14-556 167 Members of The House of Representatives and 44 US SenatorsDowning Post NewsNo ratings yet

- Kosilek Cert PetitionDocument46 pagesKosilek Cert Petitionjsnow489No ratings yet

- Social Security and Marriage Equality ActDocument2 pagesSocial Security and Marriage Equality Actjsnow489No ratings yet

- Held v. Colvin ComplaintDocument35 pagesHeld v. Colvin Complaintjsnow489No ratings yet

- Kenneth B. Mehlman Et AlDocument68 pagesKenneth B. Mehlman Et AlZeke MillerNo ratings yet

- Alabama Chief Justice Moore Memo To Probate JudgesDocument27 pagesAlabama Chief Justice Moore Memo To Probate Judgesjsnow489No ratings yet

- State Marriage Defense ActDocument3 pagesState Marriage Defense Actjsnow489No ratings yet

- Petition GrantedDocument148 pagesPetition GrantedEquality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- Alabama Gay MarriageDocument10 pagesAlabama Gay MarriagemolliereillyNo ratings yet

- Granting InjunctionDocument8 pagesGranting InjunctionChad PetriNo ratings yet

- Student Non-Discrimination ActDocument15 pagesStudent Non-Discrimination Actjsnow489No ratings yet

- 1:14-cv-00424 #29 - OrderDocument4 pages1:14-cv-00424 #29 - OrderEquality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- U.S. Supreme Court Declines To Block Same-Sex Marriages in AlabamaDocument3 pagesU.S. Supreme Court Declines To Block Same-Sex Marriages in AlabamaLGBTQ NationNo ratings yet

- Alabama Chief Justice Moore Letter To Probate JudgesDocument4 pagesAlabama Chief Justice Moore Letter To Probate Judgesjsnow489No ratings yet

- The People's BriefDocument47 pagesThe People's Briefjsnow489No ratings yet

- International Human Rights Defense Act (2015)Document19 pagesInternational Human Rights Defense Act (2015)jsnow489No ratings yet

- Alabama Same-Sex Marriage StayDocument6 pagesAlabama Same-Sex Marriage Stayjsnow489No ratings yet

- SPLC Complaint Against Chief Justice Roy MooreDocument10 pagesSPLC Complaint Against Chief Justice Roy Moorejsnow489100% (1)

- Michigan Marriage Recognition DecisionDocument47 pagesMichigan Marriage Recognition Decisionjsnow489No ratings yet

- Roy Moore LetterDocument3 pagesRoy Moore Letterjsnow489No ratings yet

- 14-823 Supreme Court Petition North Carolina Marriage CaseDocument93 pages14-823 Supreme Court Petition North Carolina Marriage CaseEquality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- Gambia Letter To President ObamaDocument2 pagesGambia Letter To President Obamajsnow489No ratings yet

- South Dakota Gay Marriage DecisionDocument28 pagesSouth Dakota Gay Marriage DecisionAshley AlmanNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- (PASTRANA) How To Write A Position PaperDocument3 pages(PASTRANA) How To Write A Position PaperNJ GeertsNo ratings yet

- Assignment #2 (The Philippines Past) RPHDocument6 pagesAssignment #2 (The Philippines Past) RPHCARL ADRIAN GUNDAYAONo ratings yet

- Metcalf & Eddy, Inc. v. Sewer Authority, 1st Cir. (1993)Document25 pagesMetcalf & Eddy, Inc. v. Sewer Authority, 1st Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Philippines vs. Lugod rape confession inadmissibleDocument1 pagePhilippines vs. Lugod rape confession inadmissibleRica100% (1)

- Cbi Deputation 1 PDFDocument8 pagesCbi Deputation 1 PDFapfc epfoNo ratings yet

- Garland Memo DOJ IG RequestDocument4 pagesGarland Memo DOJ IG RequestMaurA Dowling100% (1)

- Law Enforcement Against Use of Roadside by Street VendorsDocument13 pagesLaw Enforcement Against Use of Roadside by Street VendorsAxcellino FernandoNo ratings yet

- Nast - Corpuz OD The Roots of The Filipino Nation Vol II - 455Document7 pagesNast - Corpuz OD The Roots of The Filipino Nation Vol II - 455Kaye E. Sapungen100% (1)

- Pakistan ResolutionDocument4 pagesPakistan ResolutionImran ShehzadNo ratings yet

- Reconstituting Polomolok's Local Child Protection CouncilDocument4 pagesReconstituting Polomolok's Local Child Protection CouncilLeonard BalabatNo ratings yet

- Philippine Supreme Court Rules MIAA Airport Lands Exempt from Local Property TaxesDocument46 pagesPhilippine Supreme Court Rules MIAA Airport Lands Exempt from Local Property TaxesRYWELLE BRAVONo ratings yet

- Belgrade and Pristina: Lost in Normalisation?: by Donika Emini and Isidora StakicDocument8 pagesBelgrade and Pristina: Lost in Normalisation?: by Donika Emini and Isidora StakicRaif QelaNo ratings yet

- 19TH Century Philippines As Rizal's ContextDocument8 pages19TH Century Philippines As Rizal's Contextjaocent brixNo ratings yet

- The İdeology of Ba'ath PartyDocument7 pagesThe İdeology of Ba'ath Partyelifcevik7No ratings yet

- LIBRARYLISTOFADMINACCOUNTBOOKSDocument4 pagesLIBRARYLISTOFADMINACCOUNTBOOKSVajjala HimajaNo ratings yet

- MD Mahfuzul HaqueDocument2 pagesMD Mahfuzul HaqueMahfuz Law RuNo ratings yet

- PMMSI vs. CADocument1 pagePMMSI vs. CAKurisuchan Damnit100% (2)

- Talaroc v. Uy, The Case Relied Upon by The Lower CourtDocument2 pagesTalaroc v. Uy, The Case Relied Upon by The Lower CourtKringNo ratings yet

- Gen Ed Day 5Document9 pagesGen Ed Day 5luisgelacio19No ratings yet

- Peace and Public Safety Planning GuideDocument130 pagesPeace and Public Safety Planning GuideJose Mari TrinidadNo ratings yet

- RAMISCAL, JR. vs. SANDIGANBAYANDocument2 pagesRAMISCAL, JR. vs. SANDIGANBAYANAnn Catalan100% (1)

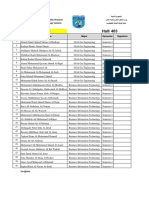

- IUT Twintech student attendance sheetDocument1 pageIUT Twintech student attendance sheetMustafa A. AlakhaliNo ratings yet

- Case Digest Loc GovDocument3 pagesCase Digest Loc GovHazel Joy Dicang TorresNo ratings yet

- Nepali Legal System IDocument1 pageNepali Legal System IDiksha PaudelNo ratings yet

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law UniversityDocument20 pagesDamodaram Sanjivayya National Law UniversitySusmita TripathyNo ratings yet

- Brokenshire V Minister of LaborDocument2 pagesBrokenshire V Minister of LaborChristian RoqueNo ratings yet

- Motion DocumentDocument8 pagesMotion DocumentNBC 10 WJARNo ratings yet

- Reflection Paper - How Logic Will Help You Develop A Legal MindDocument1 pageReflection Paper - How Logic Will Help You Develop A Legal MindStephanie Rose MarcelinoNo ratings yet

- Trade Union Movement in Nepal - Brief HistoryDocument12 pagesTrade Union Movement in Nepal - Brief HistoryRobinhoodNo ratings yet