Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Before WWI: Theories on Airspace Sovereignty (39

Uploaded by

Patrick Jorge Sibayan0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

312 views3 pagesThe document discusses the evolution of international law governing airspace and outer space. It describes early theories on sovereignty over airspace that emerged before World War 1. The 1919 Paris Convention established that nations have complete sovereignty over their airspace and the right to regulate foreign flights. The 1944 Chicago Convention reaffirmed these principles and distinguished between scheduled and unscheduled flights. For outer space, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty and subsequent agreements established principles like no national appropriation of space and that space exploration must benefit all countries.

Original Description:

international aerial sovereignty

Original Title

Aerial Domain

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe document discusses the evolution of international law governing airspace and outer space. It describes early theories on sovereignty over airspace that emerged before World War 1. The 1919 Paris Convention established that nations have complete sovereignty over their airspace and the right to regulate foreign flights. The 1944 Chicago Convention reaffirmed these principles and distinguished between scheduled and unscheduled flights. For outer space, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty and subsequent agreements established principles like no national appropriation of space and that space exploration must benefit all countries.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

312 views3 pagesBefore WWI: Theories on Airspace Sovereignty (39

Uploaded by

Patrick Jorge SibayanThe document discusses the evolution of international law governing airspace and outer space. It describes early theories on sovereignty over airspace that emerged before World War 1. The 1919 Paris Convention established that nations have complete sovereignty over their airspace and the right to regulate foreign flights. The 1944 Chicago Convention reaffirmed these principles and distinguished between scheduled and unscheduled flights. For outer space, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty and subsequent agreements established principles like no national appropriation of space and that space exploration must benefit all countries.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

Before the First World War:

1. The theory of the Institute of International Law of

1906 that the air should be absolutely free for purposes of

aerial navigation by aviators of all countries.

2. The so-called zone theory, that though the air is free

the subjacent State should have a certain right of control up

to a certain height.

3. The theory of freedom of the air coupled with an

acknowledgment of the right of the subjacent State to control

it to an indefinite height for purposes of its own protection.

4. The theory of absolute sovereignty on a parity with that

recognized as to the land domain.

5. The theory of absolute sovereignty qualified by the

right of innocent passage.

The Paris Convention of 1919 (formally, the Convention Relating to the Regulation of Aerial

Navigation)

The following principles governed the drafting of the convention:[3]

1. Each nation has absolute sovereignty over the airspace overlying its territories and waters. A

nation, therefore, has the right to deny entry and regulate flights (both foreign and domestic) into

and through its airspace.

2. Each nation should apply its airspace rules equally to its own and foreign aircraft operating

within that airspace, and make rules such that its sovereignty and security are respected while

affording as much freedom of passage as possible to its own and other signatories' aircraft.

3. Aircraft of contracting states are to be treated equally in the eyes of each nation's law.

4. Aircraft must be registered to a state, and they possess the nationality of the state in which

they are registered.

The 1944 Chicago Convention reaffirms the basic principles of customary international air law.

It provides that every State has complete and exclusive sovereignty over the airspace above its

territory.[6]

It states the principle that aircraft have the nationality of the State in which they are registered

(notably, many rules governing aircraft, provided in the Convention, have been copied from the

rules governing ships).[7]

It makes a distinction between scheduled and unscheduled air services.

No scheduled international air service of one State may be operated over or into the territory of

another State, except with the special permission or other authorization of that State, and in

accordance with the terms of such permission or authorization.[8]

Aircraft not engaged in scheduled international air services have the right to make flights into or

in transit non-stop across the territory of another State, and to make stops for non-traffic

purposes without the necessity of obtaining prior permission of that State, subject, however, to

the right of the State flown over to require landing, or to impose certain restrictions, such as

routes and off-limit areas.[9]

The Chicago Conventions applies only to civil aircraft, not to State aircraft which are used in

military, customs and police services.[10] State aircraft have no right to fly over the territory of

another State or land thereon without authorization by special agreement or otherwise, and in

accordance with the terms thereof.[11]

Wherever outer space may begin, it is governed by International Law, including the Charter of

the United Nations. The international law of outer space consists mainly of the 1967 Outer

Space Treaty,[15] the 1968 Rescue of Astronauts Agreement,[16] 1972 Liability for Damage

Caused by Space Objects Convention,[17] the 1974 Registration of Objects in Space

Convention,[18] and the 1979 Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and

Other Celestial Bodies (the Moon Treaty)

The international law of outer space provides the fundamental principles relate to the outer space.

Among these principles are:

1. Prohibition of national appropriation: Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is

not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any

other means. Outer space is the common heritage of mankind (res communis).

2. Freedom of exploration: Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is free for

exploration and use by all States without discrimination and in accordance with International Law, and

there is free access to all areas of celestial bodies.

3. The province of all mankind: The exploration and use of outer space, including the moon and other

celestial bodies, shall be carried out for the benefit and interests of all countries, irrespective of their

degree of economic or scientific development.

4. Ban on weapons of mass destruction: It is prohibited to place in orbit around the earth any objects

carrying nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction, and to install such

weapons on celestial bodies, or station such weapons in outer space in any manner.

5. The demilitarization of the moon and other celestial bodies: The moon and other celestial bodies

shall be used by all States exclusively for peaceful purposes. The establishment of military bases,

installations and fortification, the testing of any type of weapons, and the conducting of any military

actions on the celestial bodies are forbidden.

6. The liability for damages: A State launching or procuring of launching of an object into outer space,

including the moon and other celestial bodies, and the State from whose territory or facility an object is

launched is internationally liable for damages caused to another State or to its nationals by such object

or its component parts on the earth, in air space or in outer space, including the moon and other

celestial bodies.

7. Ownership of objects launched into outer space is not affected by their presence therein, or by their

return to earth.

8. A State on whose registry an object launched into outer space is carried retains jurisdiction and

control over such object, and over any personnel thereof, while in outer space or on a celestial body.

9. The duty to avoid harmful contamination and adverse changes in the environment.

10. The duty to provide assistance to space vehicles and astronauts in distress, and to return them

safely and promptly to the State of registry of their space vehicle.

11. The duty to inform the Secretary-General of the United Nations as well as the public and the

international scientific community of the nature, conduct, locations and results of their activities in

outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies.

12. The duty to open all stations, installations, equipments and space vehicles on the moon and other

celestial bodies to representatives of other States for inspection.

Despite the growing body of rules of the international law of outer space, much remains to be done,

particularly in the field of military uses of outer space, space navigation, telecommunications, and the

unresolved question related to the boundary between the airspace and outer space.

You might also like

- 4 Contract of AntichresisDocument3 pages4 Contract of AntichresisPatrick Jorge Sibayan75% (4)

- Barangay Certification For First Time JobseekersDocument1 pageBarangay Certification For First Time JobseekersPatrick Jorge Sibayan90% (58)

- Complexity and The Misguided Search For Grand Strategy, by Amy B. ZegartDocument57 pagesComplexity and The Misguided Search For Grand Strategy, by Amy B. ZegartHoover Institution75% (4)

- CBRP Orientation Workshop SummaryDocument14 pagesCBRP Orientation Workshop SummaryPatrick Jorge Sibayan100% (1)

- Sample OrdinanceDocument2 pagesSample OrdinancePatrick Jorge Sibayan100% (5)

- Alan Jenkins FinalDocument2 pagesAlan Jenkins FinallibreybreroNo ratings yet

- International LawDocument5 pagesInternational LawROBINNo ratings yet

- Space Law Born from Sputnik LaunchDocument4 pagesSpace Law Born from Sputnik LaunchRustom IbanezNo ratings yet

- EVOLUTION of Air Laws in International Law1Document11 pagesEVOLUTION of Air Laws in International Law1kingNo ratings yet

- Basic Principles of International Space LawDocument7 pagesBasic Principles of International Space Lawsindhuja dhayananthanNo ratings yet

- International LawDocument11 pagesInternational LawadeebarahmanNo ratings yet

- Global Commons and Outer Space TreatyDocument10 pagesGlobal Commons and Outer Space TreatyDeepanshu VermaNo ratings yet

- Space Law TreatiesDocument4 pagesSpace Law TreatiesraitrisnaNo ratings yet

- The Outer Space Treaty of 1967Document5 pagesThe Outer Space Treaty of 1967Rey BenitezNo ratings yet

- Application of International Environmental Law in Outer SpaceDocument13 pagesApplication of International Environmental Law in Outer SpaceBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNo ratings yet

- Space LawsDocument5 pagesSpace LawsPooja VikramNo ratings yet

- Air LawDocument14 pagesAir LawSand M CNo ratings yet

- Outer Space LawDocument4 pagesOuter Space LawRaqeeb RahmanNo ratings yet

- Air SpaceDocument36 pagesAir SpaceAyush gargNo ratings yet

- Outer Space - Common HeritageDocument15 pagesOuter Space - Common Heritageleeni liniNo ratings yet

- Space Treaty 1967Document34 pagesSpace Treaty 1967Johan RadityaNo ratings yet

- Outer Space Treaty of 1967Document6 pagesOuter Space Treaty of 1967situationsNo ratings yet

- International Air and Space Law SovereigntyDocument6 pagesInternational Air and Space Law Sovereigntythet su sanNo ratings yet

- Airspace SovereigntyDocument13 pagesAirspace Sovereigntysindhuja dhayananthanNo ratings yet

- Outer Space TreatyDocument4 pagesOuter Space TreatyKunal GuptaNo ratings yet

- Law of Air SpaceDocument2 pagesLaw of Air SpaceliaseyieNo ratings yet

- Airspace Sovereignty and Innocent PassageDocument6 pagesAirspace Sovereignty and Innocent PassageKaran SinhaNo ratings yet

- International Law and SpaceDocument7 pagesInternational Law and SpaceSanel Sanela BejdicNo ratings yet

- Space Law Treaties and PrinciplesDocument10 pagesSpace Law Treaties and PrinciplesVAISHNAVI P SNo ratings yet

- Territory Land, Air and Outer Space ReportDocument33 pagesTerritory Land, Air and Outer Space ReportCarla Jade MesinaNo ratings yet

- International Law ViolationDocument7 pagesInternational Law ViolationRatri Ayudya SariNo ratings yet

- Malaysia Aviation LawDocument87 pagesMalaysia Aviation LawMartin GohNo ratings yet

- Air&Space Law 1st AssignmentDocument6 pagesAir&Space Law 1st AssignmentKaran SinhaNo ratings yet

- HUKUM UDARA & ANGKASADocument24 pagesHUKUM UDARA & ANGKASASamuel Mierza FahmyNo ratings yet

- Air Law, The Body Of: Law International Civil Aviation Organization PoliceDocument20 pagesAir Law, The Body Of: Law International Civil Aviation Organization PoliceShakil AhmedNo ratings yet

- Five-Freedoms of Air TransportDocument11 pagesFive-Freedoms of Air TransportJamnie AgduyengNo ratings yet

- Annotated-Ence 20421 20term 20paperDocument17 pagesAnnotated-Ence 20421 20term 20paperapi-668003208No ratings yet

- Space Law: Dr. Raju KDDocument32 pagesSpace Law: Dr. Raju KDRaju KDNo ratings yet

- Myint Nandar Thein 1Document5 pagesMyint Nandar Thein 1Naing Tint LayNo ratings yet

- The Tokyo Convention, 1963 The Geneva Convention, 1948Document32 pagesThe Tokyo Convention, 1963 The Geneva Convention, 1948Mohit Raj SinghNo ratings yet

- State Sovereignty On Territory in Air Space EditDocument16 pagesState Sovereignty On Territory in Air Space EditPMO YangonNo ratings yet

- The Chicago Convention 1944Document37 pagesThe Chicago Convention 1944Denuka Dhanushka Wijerathne100% (2)

- The Chicago Convention As A Source of Internatioinal Air LAWDocument18 pagesThe Chicago Convention As A Source of Internatioinal Air LAWmenotecNo ratings yet

- Moon Treaty: ContentDocument4 pagesMoon Treaty: ContentEmmanuel C. DumayasNo ratings yet

- Uncstd BGDocument16 pagesUncstd BGAditya MNo ratings yet

- Air and SpaceDocument13 pagesAir and SpaceArthi GaddipatiNo ratings yet

- ASPL633 Space Transportation RegimeDocument19 pagesASPL633 Space Transportation RegimeShirat MohsinNo ratings yet

- Air and Space Law6482Document33 pagesAir and Space Law6482mansavi bihaniNo ratings yet

- States' Legitimate Shares in International Air and Space LawDocument31 pagesStates' Legitimate Shares in International Air and Space LawYi-Ting ChoNo ratings yet

- The Law of The AirDocument10 pagesThe Law of The AirsumayaNo ratings yet

- The Chicago Convention As A Source of Internatioinal Air LawDocument18 pagesThe Chicago Convention As A Source of Internatioinal Air LawGalih MaulanaNo ratings yet

- ATPL Law 01Document18 pagesATPL Law 01Anuar SNo ratings yet

- What is the aerial domain and jurisdiction of states in airspace and outer spaceDocument2 pagesWhat is the aerial domain and jurisdiction of states in airspace and outer spaceRomeo BullequieNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Introduction To International Aviation LawsDocument84 pagesUnit 1 Introduction To International Aviation LawsArleigh Jan Igot PangatunganNo ratings yet

- Chicago ConventionDocument6 pagesChicago ConventionJashaswee MishraNo ratings yet

- Air and SpaceDocument45 pagesAir and SpaceupendraNo ratings yet

- 7freedoms of The Air Explained CtoDocument3 pages7freedoms of The Air Explained CtoSoriano Girlie MarieNo ratings yet

- Patents in The Field of Outer SpaceDocument8 pagesPatents in The Field of Outer SpaceNavyaChopraNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3295918Document21 pagesSSRN Id3295918Hadley PanNo ratings yet

- Conventions: The Chicago ConventionDocument12 pagesConventions: The Chicago ConventionAkanksha SinghNo ratings yet

- Freedoms of The Air Explained: by Arpad Szakal LL.M. (Leiden)Document3 pagesFreedoms of The Air Explained: by Arpad Szakal LL.M. (Leiden)Zian Lyle TolilicNo ratings yet

- Territory of A State in International LawDocument34 pagesTerritory of A State in International LawPremiNo ratings yet

- 03 Consuetudine Istantanea AG Ris 1962 (Outer Space)Document2 pages03 Consuetudine Istantanea AG Ris 1962 (Outer Space)winstongattaNo ratings yet

- Coastal States' Jurisdiction Over Foreign Flag ShipsDocument24 pagesCoastal States' Jurisdiction Over Foreign Flag ShipsVinod GuptaNo ratings yet

- Barangay Disiplina Brigade EODocument3 pagesBarangay Disiplina Brigade EOPatrick Jorge Sibayan100% (3)

- Republic Act NoDocument24 pagesRepublic Act NoCriz BaligodNo ratings yet

- Barangay RPRH Law Implementing TeamDocument3 pagesBarangay RPRH Law Implementing TeamPatrick Jorge Sibayan100% (5)

- Sibayan, Patrick Jorge - Weekly Accomplishment (July 8-14, 2019)Document2 pagesSibayan, Patrick Jorge - Weekly Accomplishment (July 8-14, 2019)Patrick Jorge SibayanNo ratings yet

- BADAC Functionality Audit FY 2018 ChecklistDocument2 pagesBADAC Functionality Audit FY 2018 ChecklistPatrick Jorge Sibayan100% (25)

- Sibayan, Patrick Jorge - Weekly Accomplishment (August 5-11, 2019)Document2 pagesSibayan, Patrick Jorge - Weekly Accomplishment (August 5-11, 2019)Patrick Jorge SibayanNo ratings yet

- Local Government Training ReportDocument2 pagesLocal Government Training ReportPatrick Jorge SibayanNo ratings yet

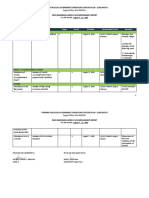

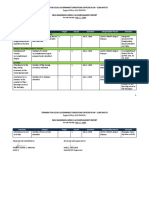

- 2017 CCPC Work and Financial PlanDocument7 pages2017 CCPC Work and Financial PlanPatrick Jorge SibayanNo ratings yet

- Abundo Vs ComelecDocument26 pagesAbundo Vs ComelecKramoel AgapNo ratings yet

- Notes March 2, 2019Document5 pagesNotes March 2, 2019Patrick Jorge Sibayan100% (1)

- Barangay Protection Order: (Date and Time)Document2 pagesBarangay Protection Order: (Date and Time)Patrick Jorge Sibayan100% (8)

- CSF - Write Up - Typhoon OmpongDocument21 pagesCSF - Write Up - Typhoon OmpongPatrick Jorge SibayanNo ratings yet

- Torts and Damages Case DigestDocument3 pagesTorts and Damages Case DigestPatrick Jorge SibayanNo ratings yet

- BCPC EoDocument3 pagesBCPC EoPatrick Jorge SibayanNo ratings yet

- Torts and Damages Case DigestDocument3 pagesTorts and Damages Case DigestPatrick Jorge SibayanNo ratings yet

- Lim Tong Lim v. Phil Fishing Gear IndustriesDocument10 pagesLim Tong Lim v. Phil Fishing Gear IndustriesPatrick Jorge SibayanNo ratings yet

- July 17, 2017 - Special Report - Declaration of Drug Unaffected Municipality With E-SigDocument2 pagesJuly 17, 2017 - Special Report - Declaration of Drug Unaffected Municipality With E-SigPatrick Jorge SibayanNo ratings yet

- Mapping and Road Network PlansDocument6 pagesMapping and Road Network PlansPatrick Jorge SibayanNo ratings yet

- 16-20 Orientation of MmtsDocument2 pages16-20 Orientation of MmtsPatrick Jorge SibayanNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court of the Philippines Rules on Registration of Panamanian Oil Company's Stock SaleDocument10 pagesSupreme Court of the Philippines Rules on Registration of Panamanian Oil Company's Stock Saleyelina_kuranNo ratings yet

- Reorganizing Barangay CommitteesDocument14 pagesReorganizing Barangay CommitteesPatrick Jorge Sibayan100% (23)

- Special Report - Declaration of Drug Unaffected MunicipalityDocument2 pagesSpecial Report - Declaration of Drug Unaffected MunicipalityPatrick Jorge SibayanNo ratings yet

- Mijares v. PiccioDocument3 pagesMijares v. PiccioPatrick Jorge SibayanNo ratings yet

- Rioferio vs. CADocument3 pagesRioferio vs. CAMaricel Caranto FriasNo ratings yet

- Assoc of LandDocument38 pagesAssoc of LandthefiledetectorNo ratings yet

- Pedro Palting v. San Jose PetroleumDocument2 pagesPedro Palting v. San Jose PetroleumPatrick Jorge SibayanNo ratings yet

- Wk2.Sex. Student HandoutDocument2 pagesWk2.Sex. Student HandoutteejmcdeeNo ratings yet

- The Core Principles of Good Corporate Governance: Let's Get Started!Document27 pagesThe Core Principles of Good Corporate Governance: Let's Get Started!Relena Darlian ObidosNo ratings yet

- Justo V GalingDocument5 pagesJusto V GalingCrmnmarieNo ratings yet

- Probation Law of 1976Document3 pagesProbation Law of 1976Roland MarananNo ratings yet

- Organization Associated With Biodiversity Organization-Methodology For Execution IucnDocument45 pagesOrganization Associated With Biodiversity Organization-Methodology For Execution IucnmithunTNNo ratings yet

- Fields IndictmentDocument8 pagesFields IndictmentJenna Amatulli100% (1)

- From Utopian Dream To Dystopian Reality George Orwell's Animal Farm, Bahareh Darvish & Mohammedreza NajjarDocument7 pagesFrom Utopian Dream To Dystopian Reality George Orwell's Animal Farm, Bahareh Darvish & Mohammedreza NajjardumbbeauNo ratings yet

- Republic of The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesRepublic of The PhilippinesMc SuanNo ratings yet

- CIVL5266 2019 Semester 1 Student-1Document5 pagesCIVL5266 2019 Semester 1 Student-1Dhurai Raj AthinarayananNo ratings yet

- (Torts) 67 - Rodrigueza V The Manila Railroad Company - LimDocument3 pages(Torts) 67 - Rodrigueza V The Manila Railroad Company - LimJosiah LimNo ratings yet

- Commercial Law DigestDocument19 pagesCommercial Law DigestJohndale de los SantosNo ratings yet

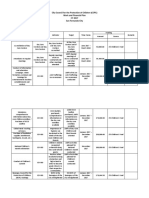

- Elvina B. Canipas Ipcrf 2015 2016Document21 pagesElvina B. Canipas Ipcrf 2015 2016LeonorBagnison67% (3)

- (Cô Vũ Mai Phương) Tài liệu LIVESTREAM - Tổng ôn 2 tuần cuối - Dự đoán câu hỏi Collocation trong đề thiDocument2 pages(Cô Vũ Mai Phương) Tài liệu LIVESTREAM - Tổng ôn 2 tuần cuối - Dự đoán câu hỏi Collocation trong đề thiMon MonNo ratings yet

- Sikolohiyang PilipinoDocument9 pagesSikolohiyang PilipinoMargielane AcalNo ratings yet

- By Deepak Mangal Harkesh Gurjar Sanjay GuptaDocument22 pagesBy Deepak Mangal Harkesh Gurjar Sanjay GuptaagyeyaNo ratings yet

- Montejo vs. Commission On Audit DigestDocument2 pagesMontejo vs. Commission On Audit DigestEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- History GabrielaDocument10 pagesHistory Gabrielaredbutterfly_766No ratings yet

- Management Ethics Guide: Meaning, Need, Importance & Best PracticesDocument11 pagesManagement Ethics Guide: Meaning, Need, Importance & Best PracticesAbdullah MujahidNo ratings yet

- Ethics and Values: A Comparison Between Four Countries (United States, Brazil, United Kingdom and Canada)Document15 pagesEthics and Values: A Comparison Between Four Countries (United States, Brazil, United Kingdom and Canada)ahmedNo ratings yet

- Book ReviewDocument2 pagesBook ReviewFong CaiNo ratings yet

- Principles of TQMDocument2 pagesPrinciples of TQMmacNo ratings yet

- BPI Vs Lifetime Marketing CorpDocument8 pagesBPI Vs Lifetime Marketing CorpKim ArizalaNo ratings yet

- 2.2 Razon V InciongDocument8 pages2.2 Razon V InciongSheena Reyes-BellenNo ratings yet

- A Terrible StateDocument20 pagesA Terrible StateAustin Macauley Publishers Ltd.No ratings yet

- Law and OrderDocument12 pagesLaw and OrderPraveen KumarNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Governance Among The Southern Afar (Ca.1815-1974), EthiopiaDocument25 pagesIndigenous Governance Among The Southern Afar (Ca.1815-1974), Ethiopiathitina yohannesNo ratings yet

- James Midgley Perspectives On Globalization and Culture - Implications For International Social Work PracticeDocument11 pagesJames Midgley Perspectives On Globalization and Culture - Implications For International Social Work PracticemasnoerugmNo ratings yet

- Group Interview Insights on University Social SpacesDocument2 pagesGroup Interview Insights on University Social SpacesFizzah NaveedNo ratings yet