Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Comparative Studies in Germanic Syntax (Linguistik Aktuell 97)

Uploaded by

Trajano1234Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Comparative Studies in Germanic Syntax (Linguistik Aktuell 97)

Uploaded by

Trajano1234Copyright:

Available Formats

Comparative Studies in Germanic Syntax

<DOCINFO AUTHOR ""TITLE "Comparative Studies in Germanic Syntax: From A(frikaans) to Z(urich German)"SUBJECT "Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today, Volume 97"KEYWORDS ""SIZE HEIGHT "240"WIDTH "160"VOFFSET "4">

Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today

Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today (LA) provides a platform for original monograph studies

into synchronic and diachronic linguistics. Studies in LA confront empirical and theoretical

problems as these are currently discussed in syntax, semantics, morphology, phonology, and

systematic pragmatics with the aim to establish robust empirical generalizations within a

universalistic perspective.

Series Editors

Werner Abraham

University of Vienna

Elly van Gelderen

Arizona State University

Advisory Editorial Board

Cedric Boeckx

Harvard University

Guglielmo Cinque

University of Venice

Gnther Grewendorf

J.W. Goethe-University, Frankfurt

Liliane Haegeman

University of Lille, France

Hubert Haider

University of Salzburg

Christer Platzack

University of Lund

Ian Roberts

Cambridge University

Ken Sar

Rutgers University, New Brunswick NJ

Lisa deMena Travis

McGill University

Sten Vikner

University of Aarhus

C. Jan-Wouter Zwart

University of Groningen

Volume 97

Comparative Studies in Germanic Syntax: From Afrikaans

to Zurich German

Edited by Jutta M. Hartmann and Lszl Molnr

Comparative Studies

in Germanic Syntax

From Afrikaans to Zurich German

Edited by

Jutta M. Hartmann

Lszl Molnr

Tilburg University

John Benjamins Publishing Company

Amsterdam / Philadelphia

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements

8

TM

of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence

of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Workshop on Comparative Germanic Syntax (20th ; Tilburg, Netherlands)

Comparative studies in Germanic syntax : from Afrikaans to Zurich German /

edited by Jutta M. Hartmann, Lszl Molnr.

p. cm. (Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today, issn 01660829 ; v. 97)

Selected papers presented at the 20th Comparative Germanic Syntax

Workshop held in June, 2005, in Tilburg.

1. Germanic languages--Syntax--Congresses. I. Hartmann, Jutta. II.

Molnr, Lszl, 1971-

PD361 .W67 2005

435--dc22 2006050841

isbn 90 272 3361 6 (Hb; alk. paper)

2006 John Benjamins B.V.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microlm, or

any other means, without written permission from the publisher.

John Benjamins Publishing Co. P.O. Box 36224 1020 me Amsterdam The Netherlands

John Benjamins North America P.O. Box 27519 Philadelphia pa 19118-0519 usa

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 10:39 F: LA97CO.tex / p.1 (47-96)

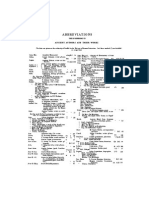

Table of contents

From Afrikaans to Zurich German: Comparative studies

in Germanic syntax 1

Jutta M. Hartmann & Lszl Molnr

I. Studies on predication

The Nom/Acc alternation in Germanic 13

Halldr rmann Sigursson

Shape conservation, Holmbergs generalization and predication 51

Olaf Koeneman

Quirky verb-second in Afrikaans: Complex predicates and head movement 89

Mark de Vos

Nominal arguments and nominal predicates 115

Marit Julien

II. Studies on the (pro)nominal system

Pronominal noun phrases, number specications, and null nouns 143

Dorian Roehrs

Toward a syntactic theory of number neutralisation:

The Dutch pronouns je you and ze them 181

Gertjan Postma

Long relativization in Zurich German as resumptive prolepsis 201

Martin Salzmann

III. Historical studies

Auxiliary selection and counterfactuality in the history of English

and Germanic 237

Thomas McFadden and Artemis Alexiadou

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 10:39 F: LA97CO.tex / p.2 (96-105)

v: Table of contents

The loss of residual head-nal orders and remnant fronting in Late

Middle English: Causes and consequences 263

Mary Theresa Biberauer and Ian Gareth Roberts

Syntactic sources of word-formation processes: Evidence from

Old English and Old High German 299

Carola Trips

Index 329

JB[v.20020404] Prn:22/09/2006; 8:33 F: LA97IN.tex / p.1 (46-118)

From Afrikaans to Zurich German

Comparative studies in Germanic syntax

Jutta M. Hartmann & Lszl Molnr

Tilburg University

The present volume contains a selection of papers presented at the 20th Com-

parative Germanic Syntax Workshop in Tilburg, June 2005. While following a

tradition of earlier CGSW-proceedings the contributions cover a wide range of

Germanic languages as well as a wide range of current topics in modern syntactic

theory, the selection also shows a strong comparative commitment. Such commit-

ment might seem evident. Indeed, the relevance of the comparative methodology

for modern syntax, and more specically for a theory of UG, can hardly be dis-

puted. To some extent, syntactic theorizing is meaningless without observing,

describing, comparing (and, in the ideal case, explaining) varieties or variations

of a specic language phenomenon occurring cross-linguistically or in different

historical stages of a given language. The aim is to nd and to control the cross-

linguistically relevant contrasts that do not go back to external factors, but can be

explained as reexes of the same difference in the grammar of the given languages,

contributing to our better understanding of the architecture of UG.

Yet, the editors of the present volume feel (and, as we believe, this sentiment

is shared by many) that the comparative aspect of CGSW has somewhat weakened

in recent years and needs to be addressed in a proper way. Only if comparative

studies offer more than just non-systematic side-glances to other languages can

important generalizations be captured and real explanatory power achieved (cf.

especially Haider 1993 or Abraham1995 in this regard). For that reason we wanted

to take the notion comparative and Germanic in the title of the Workshop

seriously, and asked for contributions that address at least two Germanic languages

(or different diachronic stages of the same Germanic language) in depth, or discuss

a specic grammatical phenomenon of a given language in the overall Germanic

perspective.

Heeding this truly comparative perspective, the essays in this volume celebrate

variety both with respect to the languages investigated and the topics addressed.

JB[v.20020404] Prn:22/09/2006; 8:33 F: LA97IN.tex / p.2 (118-177)

i Jutta M. Hartmann & Lszl Molnr

The editors particularly welcome that besides the usual suspects (i.e. English

and German) and recurring guests (i.e. the Scandinavia) of the CGSW-series,

we could include here studies on lesser-investigated languages such as modern

Afrikaans and Zurich German. The volume has also beneted from a strong his-

torical component, including studies on linguistic aspects of various diachronic

stages of English and German. Here, the emphasis often lies on intralinguistic,

rather than cross-linguistic variety, the methodology of comparison facing partic-

ular challenges in terms of adequate collection and evaluation of historical data

(see particularly McFadden & Alexiadous contribution in this respect).

While covering a wide range of current issues in linguistics, the present col-

lection of essays can be subsumed under three major thematic headings. The rst

part of the volume contains comparative studies on predication in Germanic, ad-

dressing issues such as case dependency in the domain of predication (Sigursson),

constraints of movement preserving or distorting thematic relations (Koeneman)

or a quirky case of complex predicate formation in Afrikaans (de Vos). The

second part of the volume contains papers on the (pro)nominal domain in Ger-

manic, including studies on the licensing conditions of pronominal noun phrases

(Roehrs), number neutralization in the Dutch pronominal system (Postma) and

resumptive pronouns in Zurich German (Salzmann). The last part of the vol-

ume looks at Germanic syntax from a diachronic perspective, taking up on issues

such as auxiliary selection in the history of English and, more generally, in Ger-

manic (McFadden & Alexiadou), remnant fronting in Middle English (Biberauer

& Roberts) and syntactic sources of word-formation processes in Old English and

Old High German (Trips). Thus, the volume presents a wide range of studies that

enrich both theoretical understanding and empirical foundation of comparative

research on the Germanic languages.

The Nom/Acc alternation in Germanic by Halldr rmann Sigursson de-

scribes the distribution of accusative case and discusses the nature of the nomi-

native/accusative distinction in the standard Germanic languages. In addition, it

illustrates and discusses the well-known fact that inherent accusatives and certain

other types of accusatives do not behave in accordance with Bruzios Generaliza-

tion. In spite of these Non-Burzionian accusatives, there is a general dependency

relation between the so-called structural cases, Nom and Acc, here referred to

as the relational cases, such that relational Acc is licensed only in the presence of

Nom (as has been argued by many). This relation is here referred to as the Sibling

Correlation, SC. Contrary to common belief, however, SC is not a structural cor-

relation, but a simple morphological one, such that Nom is the rst, independent

case, CASE1 (an only child or an older sibling, as it were), whereas Acc is the

second, dependent case, CASE 2, serving the sole purpose of being distinct from

Nom the Nom-Acc distinction, in turn, being a morphological interpretation

or translation of syntactic structure. It has been an unresolved (and largely a ne-

JB[v.20020404] Prn:22/09/2006; 8:33 F: LA97IN.tex / p.3 (177-233)

From Afrikaans to Zurich German

glected) problem that the Germanic languages split with respect to case-marking

of predicative DPs: nominative versus accusative (It is I/me, etc.). However, the

morphological approach to the relational cases argued for in this paper offers a

solution to this riddle: The predicative Acc languages have extended the domain

of the Sibling Correlation, such that it applies not only to arguments but also to

adjacent DPs in general. That is, the English type of predicative Acc is not default,

nor is it caused by grammatical viruses, but a well-behaved subtype of relational

Acc. The central conclusion of the paper is that one needs to abandon the struc-

tural approach to the relational cases in favor of a more traditional morphological

understanding. However, this is not a conservative but a radical move. It requires

that we understand morphology (and PF in general) not as a direct reection of

syntax but as a translation of syntax into an understandable but foreign code or

language, the language of morphology. Nom and Acc are not syntactic features

but morphological translations of syntactic correlations. It is thus no wonder that

they are uninterpretable to the semantic interface.

Olaf Koenemans Shape conservation, Holmbergs generalization and predi-

cation builds on all the previous approaches to Shape Conservation and tries to

solve some problems that arise with them (in particular, related to A-movement

in passive constructions). It is argued that Holmbergs Generalization is a syntac-

tic and not a phonological phenomenon. This view allows the author to generalize

over a larger set of facts in the following way: Within the thematic domain, it is im-

possible to invert the relationships of thematic categories, i.e. categories assigning

or receiving a -role. The reason is that the grammar wants the interface interpre-

tations at LF and PF to be uniform. It is shown that notorious counterexamples

to thematic isomorphism, such as passivization and short verb movement, can be

dealt with in a unied way by making reference to predication theory.

Mark de Vos Quirky verb-second in Afrikaans: complex predicates and head

movement discusses a special case of complex predicate formation in modern

Afrikaans. The central aim of the paper is to give a novel account for Quirky Verb

Second, a peculiar construction in Afrikaans which optionally pied-pipes a coordi-

nated verbal cluster to verb-second position. Afrikaans is a verb-second language

that also allows the formation of a coordinated verb cluster: [POSTURE VERB]

[AND] [LEXICAL VERB]. The construction is putatively pseudo-coordinative in

character and typically occurs with aspectual verbs of posture. Either the posture

verb may undergo verb-second individually or, alternatively, the entire coordi-

nated verbal complex may undergo verb second. This construction is puzzling

on a number of grounds. If verb second includes head movement from at V to

at least T (Den Besten 1989), then the optional pied-piping of a phrase-like el-

ement is puzzling. However, if verb-second involves phrasal remnant movement

(Mller 2004), then the optional ability of the posture verb to be extracted from a

coordinate structure (in violation of the Coordinate Structure Constraint (Ross

JB[v.20020404] Prn:22/09/2006; 8:33 F: LA97IN.tex / p.4 (233-288)

| Jutta M. Hartmann & Lszl Molnr

1967)) is equally puzzling. This dilemma places this construction in a unique

position of being able to distinguish between these two opposing views of verb-

second. The paper proceeds by outlining the properties of the pied-piped vs. the

non-pied-piped construction. It is demonstrated that the pied-piped coordinated

constituent is indeed a verbal head. It is also shown that the base, non-pied-piped

structure is phrasal. A variety of tests are used to provide converging evidence for

these claims. Crucial evidence fromseparable particle placement is used to demon-

strate that a remnant-movement analysis would be untenable. The analysis is

couched in terms of true coordination in other words, the pseudo-coordinative

character of the construction is derived from the properties of the phrase struc-

ture itself rather than the properties of the coordinator. Coordination is argued to

scope over individual aspectual features within the verbal cluster itself. This means

that under certain special conditions, individual phonological features are not

within the scope of coordination, allowing them to undergo verb-second without

violating the Coordinate Structure Constraint. Thus, it is argued that verbal head-

movement may indeed be phonological feature movement (Boeckx & Stjepanovic

2001; Chomsky 2000; Zwart 1997), but with the added caveat that it can also be

true syntactic movement in certain instances. The proposal has implications for

theories of head movement, excorporation and coordination.

In Nominal arguments and nominal predicates, Marit Julien argues that the

claim that predicative nominal phrases are structurally smaller than argumental

nominal phrases is not corroborated by Scandinavian. For one thing, singular

nominals without determiners, which are structurally smaller than DPs, can be

predicates or arguments. Even more strikingly, it appears that full DPs, and even

larger phrases, can also be predicates as well as arguments in Scandinavian. To

show this, Julien rst sets out to identify a number of predicate tests, and then

applies these tests to Scandinavian nominal phrases of various sizes. The conclu-

sion is that DPs can clearly be predicates, and so can phrases where a universal

quantier has a DP as its complement. Hence, the difference between nominal ar-

guments and nominal predicates cannot be linked to the presence or absence of

a D-projection. Nominal phrases containing demonstratives are however not ac-

ceptable as predicates. The reason might well be a purely semantic one, having to

do with the deictic content of the demonstrative. The conclusion will be that the

contrast between nominal arguments and nominal predicates is not structural but

semantic. If the lexical content of a nominal phrase is such that the phrase can get

a purely intentional interpretation, the phrase can be a predicate, but if its lexical

content requires an extensional reading, the phrase is necessarily referential and

cannot be used to predicate.

Dorian Roehrs Pronominal noun phrases, number specications, and null

nouns deals with the licensing conditions of pronominal nouns phrases in Ger-

manic. According to standard assumptions, the determiner and the head noun

JB[v.20020404] Prn:22/09/2006; 8:33 F: LA97IN.tex / p.5 (288-322)

From Afrikaans to Zurich German ,

in the DP exhibit morphological agreement. Adopting the Postalian view, Roehrs

starts with the observation that pronominal determiners require semantic, rather

than morphological, agreement. Concentrating on number, he demonstrates in

detail that these standard assumptions are not only too weak, allowing ungram-

matical cases such as *du verdammtes Pack you(SG) damn gang, but also too

strong, disallowing grammatical examples such as ihr verdammtes Pack you(PL)

damn gang. In order to provide a uniform and homogenous account of the de-

terminer system, he proposes that pronominal determiners must agree with their

head noun not only semantically but also morphologically. Morphologically dis-

agreeing nouns are argued to be in a Specier position and the head of the

extended noun phrase hosting that Specier is a null noun. Specically, Roehrs

proposes that both regular and pronominal determiners are the same with regard

to morphological agreement; however, they differ in their semantic denotations

and syntactic selectional features: while regular determiners are dened as general

totality extractors and may select AgrP and NP, pronominal ones pick out sin-

gle or multi-member sets and select not only AgrP and NP but also the phrase with

the dis-agreeing Specier. He concludes that regular determiners are less specied

pronominal determiners. More generally, arguing that semantic number is part

of the semantics, he proposes that morphological and semantic numbers are to

be dissociated from one another. Another consequence of the discussion is that

the inventory of null nouns is extended from null countable and mass nouns (cf.

Panagiotidis 2002) to collective nouns, pluralia tantum, and proper names.

Martin Salzmanns Long relativization in Zurich German as resumptive pro-

lepsis addresses the issue that, standing out among Germanic languages, Zurich

German (ZG) employs resumptive pronouns in relativization. There is an in-

triguing asymmetry in the distribution of resumptives: while resumptives are

limited to oblique positions in local relativization, they appear across the board

in long-distance relativization. This suggests that there is a fundamental differ-

ence between the two constructions. The paper reanalyzes a previous approach

by van Riemsdijk where long-distance relativization in ZG is re-interpreted as lo-

cal aboutness relativization plus binding. The construction can be shown to have

paradoxical properties: On the one hand, there is reconstruction into the position

occupied by the resumptive pronoun, on the other hand, the complement clause

turns out to be an island for extraction. This paradox is resolved by assuming a

tough-movement style analysis: Operator movement in the complement clause de-

rives a predicate and licenses an extra argument in the matrix clause, the proleptic

object. This in turn is A-moved and deleted under identity with the external head.

This predication analysis makes an alternative reconstruction strategy available as

in tough-movement and accounts for the opacity of the complement. The link be-

tween the proleptic object and the operator in the complement clause is an ellipsis

operation. Together with concomitant Vehicle Change effects this nicely explains

JB[v.20020404] Prn:22/09/2006; 8:33 F: LA97IN.tex / p.6 (322-376)

o Jutta M. Hartmann & Lszl Molnr

the intricate Condition C pattern in both the proleptic construction and in tough-

movement. The presence of a resumptive pronoun follows from a constraint that

requires specic chains to be phonetically realized in ZG. The entire structure rep-

resents what Salzmann calls resumptive prolepsis. On a more theoretical level,

this approach suggests a straightforward way of handling exceptional and hitherto

ill-understood cases of reconstructionwithin a theory that makes crucial use of full

copies of the antecedent. It unies resumptive prolepsis with tough-movement in

crucial respects and thereby provides a fresh look at the latter.

In Gertjan Postmas Toward a syntactic theory of feature neutralization

Kaynes (2000) syntactic theory of feature neutralisation is adopted and adapted to

account for two cases of number neutralisation in Dutch, as well as a correlation

across Germanic between the presence of number neutralisation in the nomina-

tive paradigm and the type of V2 attested in those languages. The weak Dutch

object pronoun, oblique pronoun, and possessive pronoun je you is both singu-

lar and plural. In traditional terms: je exhibits number neutralization. However,

this property of je is dependent on the syntactic context: only if je is bound, it

can be both singular and plural. If not, only the singular reading is retained. To

get a plural reading the use of the complex plural form jullie you.PL is the only

option. One way to handle this theoretically is to assume two distinct forms je

with the same phonological matrix, an anaphoric pronoun je which has number

neutralisation, and a pronominal pronoun je which is singular. It is shown that

this option leads to problems with the binding theory and needs various unattrac-

tive ad hoc stipulations. Postma follows Kayne (2000), who shows that Italian s

is part of the singular paradigm. Nevertheless, it can be used as a plural: it ac-

quires plural readings by an abstract distributor, DIST, which occupies a syntactic

slot and has syntactic properties, such as the requirement that it must be bound

by a plural antecedent. Kaynes theory can be considered as a syntactisation of

morphological neutralisation. This theory is straightforwardly applicable to the

Dutch data listed above. It predicts a deep link between anaphoric behaviour and

number neutralisation. The main objective of the paper is to apply Kaynes theory

to a diachronic problem. The Middle-Dutch 3rd person pronoun hem him dis-

played number neutralisation (it could mean both him and them), and could

be used anaphorically (himselves/themselves). Modern Dutch lost this prop-

erty. Recent data (Postma 2004) show that the loss of number neutralisation in

hem goes hand in hand with the loss of its anaphoric use. To ll the gap left by

anaphoric hem, Dutch borrowed the reexive zich from German border dialects.

This newly acquired form, once again, has number neutralisation. This conrms

the link between number neutralisation and anaphoricity, as suggested by Kayne.

In the paper Auxiliary selection and counterfactuality in the history of En-

glish and Germanic by Thomas McFadden and Artemis Alexiadou, the retreat

of be as perfect auxiliary is examined in a diachronic perspective. Corpus data

JB[v.20020404] Prn:22/09/2006; 8:33 F: LA97IN.tex / p.7 (376-429)

From Afrikaans to Zurich German

are presented showing that the initial advance of have was most closely connected

to a restriction against be in past counterfactuals. Other factors which have been

reported to favor the spread of have, are either dependent on the counterfactual ef-

fect, or signicantly weaker in comparison. It is argued that the effect can be traced

to the semantics of the be perfect, which denoted resultativity rather than ante-

riority proper. Related data from other older Germanic and Romance languages

are presented, and nally implications for existing theories of auxiliary selection

stemming from the ndings presented are discussed.

Theresa Biberauers and Ian Roberts The loss of residual head-nal orders

and remnant fronting in Late Middle English: causes and consequences is a fur-

ther contribution to the ongoing discussion of the possible triggers of word order

change in Middle English (ME). The primary empirical focus of the paper is the

residual head-nal orders found in ME. The usual chronology for the general

change from OV to VO in English situates it in Early ME (Canale 1978; van Ke-

menade 1987; Lightfoot 1991; Roberts 1997; Kroch & Taylor 1994; Fischer et al.

2000), but as various authors have pointed out, orders which are indicative of

some kind of persisting OV grammar are found, albeit at rather low frequency

and somewhat disguised by other factors, until the 15th century (see Fischer et al.

2000: 177 for a summary and references). Here the authors will propose an analysis

of these orders which supports the novel proposal in Biberauer & Roberts (2005;

henceforth: B&R) that the loss of residual head-nal orders is related to the in-

troduction of obligatory clause-internal expletives. The reason for this is that both

developments result from the loss of vP-movement to SpecTP and its replacement

by DP-movement to that position. The orders that are investigated include the so-

called Stylistic Fronting (Styl-F), SVAux sequences and what has been analysed as

Verb Projection Raising (VPR), i.e. AuxOV sequences. Following and developing

the proposals in B&R, new analyses of these orders are proposed. B&R also inte-

grate the observations and analysis of van der Wurff (1997, 1999) regarding the

last attested OV orders with non-pronominal DPs. Furthermore, it is shown how

the changes that B&R propose for Late ME created some of the preconditions for

the well-known development of a syntactically distinct class of modal auxiliaries

in the 16th century (Lightfoot 1979; Roberts 1985, 1993; Warner 1997; Roberts &

Roussou 2003; Biberauer & Roberts 2006a, b).

Carola Trips Syntactic Sources of word-formation processes surveys word-

formation from a diachronic perspective and the question of whether word-

formations are built by the same principles that govern syntax. It is assumed that

word-formations like compounds and derivations historically start out as syntac-

tic phrases and in the process of becoming morphological phrases lose structural

syntactic properties like maximal projections and functional categories as well as

semantic properties like e.g. referentiality. This is shown with diachronic data

from German and English focusing on the phenomena of the development of

JB[v.20020404] Prn:22/09/2006; 8:33 F: LA97IN.tex / p.8 (429-509)

8 Jutta M. Hartmann & Lszl Molnr

sufxes like Modern English -hood, Modern German -heit, and the rise of geni-

tive compounds. Based on these ndings it will be claimed that an analysis like

Lieber (1992) or Ackema (1999) assuming that morphological operations are gov-

erned by syntactic principles is not borne out and that word-formation operations

have to be attributed to an independent module of word-formation subject to its

own governing principles. Nevertheless, the rise of genitive compounds shows that

new syntactic structures can occur once old syntactic structures have developed

into morphological structures implying that there is interaction between syntax

and morphology. Thus, looking at word-formation from a diachronic perspective

provides new insights into the nature and place of morphology.

References

Abraham, W. (1995). Deutsche Syntax im Sprachenvergleich: Grundlegung einer typologischen

Syntax des Deutschen. Tbingen: Gunter Narr.

Ackema, P. (1999). Issues in Morphosyntax [Linguistik Aktuell/ Linguistics Today]. Amsterdam:

John Benjamins.

Biberauer, T. & Roberts, I. (2005). Changing EPP parameters in the history of English:

accounting for variation and change. English Language and Linguistics, 9, 546.

Biberauer, T. & Roberts, I. (2006a). Cascading parameter changes: Internally driven change

in Middle and Early Modern English. Forthcoming in T. Eythrsson & J. T. Faarlund

(Eds.), Grammatical Change and Linguistic Theory: the Rosendal Papers. Amsterdam and

Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Biberauer, T. & Roberts, I. (2006b). Subjects, tense and verb movement in Germanic in

Romance. Forthcoming in Proceedings of GLOW V in Asia.

Boeckx, C. & Stjepanovic, S. (2001). Head-Ing Toward PF. Linguistic Inquiry, 32, 345355.

Canale, M. (1978). Word Order Change in Old English: Base reanalysis in generative grammar.

PhD dissertation, McGill University.

Chomsky, N. (2000). Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In R. Martin, D. Michaels, & J.

Uriagereka (Eds.), Step by Step (pp. 89155). Cambridge MA: The MIT Press. Reprinted.

Den Besten, H. (1989). Studies in West Germanic Syntax. Ph.D. thesis, Katholieke Universiteit

Brabant, Tilburg, Amsterdam.

Fischer, O., van Kemenade, A., Koopman, W., & van der Wurff, W. (Eds.). (2000). The Syntax of

Early English. Cambridge: CUP.

Haider, H. (1993). Deutsche Syntax Generativ. Tbingen: Gunter Narr.

Kayne, R. S. (2000). Person morphemes and reexives in Italian, French and related languages.

In R. S. Kayne, Parameters and Universals [Oxford Studies in Comparative Syntax] (pp.

131162). Oxford: OUP.

van Kemenade, A. (1987). Syntactic Case and Morphological Case in the History of English.

Dordrecht: Foris.

Kroch, A. & Taylor, A. (1994). Remarks on XV/VX alternation in Early Middle English.

Unpublished ms., University of Pennsylvania.

Lieber, R. (1992). Deconstructing Morphology. Chicago IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Lightfoot, D. (1979). Principles of Diachronic Syntax. Cambridge: CUP.

JB[v.20020404] Prn:22/09/2006; 8:33 F: LA97IN.tex / p.9 (509-570)

From Afrikaans to Zurich German

Lightfoot, D. (1991). How to Set Parameters: Arguments from language change. Cambridge MA:

The MIT Press.

Mller, G. (2004). Verb-Second as vP First. Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics, 7, 179

234.

Panagiotidis, P. (2002). Pronouns, Clitics and Empty Nouns. Pronominality and licensing in

syntax. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Postma, G. (2004). Structurele tendensen in de opkomst van het reexief pronomen zich in het

15de-eeuwse Drenthe en de Theorie van Reexiviteit. Nederlandse Taalkunde, 9, 144168.

Roberts, I. (1985). Agreement parameters and the development of the English modal auxiliaries.

Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 3, 2158.

Roberts, I. (1993). Verbs and Diachronic Syntax. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Roberts, I. (1997). Directionality and word order change in the history of English. In A. van

Kemenade & N. Vincent (Eds.), Parameters of Morphosyntactic Change (pp. 397426).

Cambridge: CUP.

Roberts, I. &Roussou, A. (2003). Syntactic Change. Aminimalist approach to grammaticalization.

Cambridge: CUP.

Ross, J. R. (1967). Constraints on Variables in Syntax. PhD dissertation, Massachusetts Institute

of Technology.

Warner, A. (1997). The structure of parametric change and V-movement in the history of

English. In A. van Kemenade & N. Vincent (Eds.), Parameters of Morphosyntactic Change

(pp. 380393). Cambridge: CUP.

van der Wurff, W. (1997). Deriving object-verb order in late Middle English. Journal of

Linguistics, 33, 485509.

van der Wurff, W. (1999). Objects and verbs in Modern Icelandic and fteenth-century English:

A word order parallel and its causes. Lingua, 109, 237265.

Zwart, J. W. (1997). Morphosyntax of Verb Movement: A minimalist approach to the syntax of

Dutch [Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory]. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

JB[v.20020404] Prn:23/08/2006; 15:15 F: LA97P1.tex / p.1 (47-74)

v.v1 i

Studies on predication

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 12:01 F: LA9701.tex / p.1 (47-153)

The Nom/Acc alternation in Germanic

Halldr rmann Sigursson

Lund University, Sweden

This paper describes the distribution of accusative case and discusses the nature

of the nominative/accusative distinction in the standard Germanic languages. In

addition, it illustrates and discusses the well-known fact that inherent accusatives

and certain other types of accusatives do not behave in accordance with Bruzios

Generalization. In spite of these Non-Burzionian accusatives, there is a general

dependency relation between the so-called structural cases, Nom and Acc, here

referred to as the relational cases, such that relational Acc is licensed only in the

precense of Nom (as has been argued by many). This relation is here referred to

as the Sibling Correlation, SC. Contrary to common belief, however, SC is not a

structural correlation, but a simple morphological one, such that Nom is the

rst, independent case, case 1 (an only child or an older sibling, as it were),

whereas Acc is the second, dependent case, case 2, serving the sole purpose of

being distinct from Nom the Nom-Acc distinction, in turn, being a morphol-

ogical inerpretation or translation of syntactic structure. It has been an unre-

solved (and largely a neglected) problem that the Germanic languages split with

respect to case-marking of predicative DPs: nominative versus accusative (It is

I/me, etc.). However, the morphological approach to the relational cases argued

for in this paper offers a solution to this riddle: The predicative Acc languages

have extended the domain of the Sibling Correlation, such that it does not apply

to only arguments but to adjacent DPs in general. That is, the English type of

predicative Acc is not default, nor is it caused by grammatical viruses, but a

well-behaved subtype of relational Acc. The central conclusion of the paper is

that we need to abandon the structural approach to the relational cases in favor

of a more traditional morphological understanding. However, this is not a

conservative but a radical move. It requires that we understand morphology (and

PF in general) not as a direct reection of syntax but as a translation of syntax

into an understandable but foreign code or language, the language of morphol-

ogy. Nom and Acc are not syntactic features but morphological translations of

syntactic correlations. It is thus no wonder that they are uninterpretable to the

semantic interface.

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 12:01 F: LA9701.tex / p.2 (153-203)

:| Halldr rmann Sigursson

:. Introduction

*

In this paper I discuss the distribution of accusative case and the nature of the

nominative/accusative distinction in the Germanic languages. In generative ap-

proaches (Chomsky 1981; Burzio 1986, etc.), three different kinds of accusatives

have been generally assumed: Structural (object) accusatives, default accusatives,

and other non-structural accusatives, as described with English examples in (1):

(1) a. She saw me. structural Acc

b. It is me. default Acc

c. I arrived the second day. other non-structural Acc

The class other non-structural Acc includes not only adverbial accusatives but

also inherent accusatives.

I will here adopt a different view, arguing that there are basically only two ac-

cusative types: Relational Acc, and Non-relational Acc, where the notion relational

means dependent on the presence of a nominative DP. On this view, so-called de-

fault, predicative accusatives are a well-behaved subtype of Relational Acc. Many of

the Germanic languages, however, apply nominative case-marking of predicative

DPs. This predicative Nom/Acc variation is a central topic of this work.

In Section 2, I discuss Burzios Generalization (BG) and describe accusative

case-marking in the Germanic languages, concentrating on accusatives that are

apparent or real exceptions to BG, in particular accusative subjects and the above

mentioned predicative accusatives. Section 3 argues for a morphological, non-

syntactic understanding of the relational (structural) cases, where Nom is seen

* I would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for insightful comments. For helpful discus-

sions, comments and corrections, many thanks also to Anders Holmberg, Andrew McIntyre,

Cecilia Falk, Christer Platzack, Heidi Quinn, Janne Bonde Johannessen, Joan Maling, Jhanna

Bardal, Kjartan Ottosson, Lois Lopez, Marit Julien, and Verner Egerland. The ideas pursued

here have, to a varying extent, been presented at several occasions: The 19th Grammar in Focus

(GIF) in Lund, February 2005, CGSW 20 in Tilburg, June 2005, and the Linguistics Department

in Konstanz in July 2005. Many thanks to the organizers of these events and to the audiences.

In particular, I wish to express my gratitude to Ellen Brandner and her co-workers in Konstanz.

For generous help with data, many thanks to: Heidi Quinn, Andrew McIntyre, Joan Maling, Di-

anne Jonas (English), Marcel den Dikken, Sjef Barbiers, Hilda Koopman, Jan-Wouter Zwart

(Dutch), Jarich Hoekstra (North and West Frisian), Theresa Biberauer (Afrikaans), Beatrice

Santorini, Sten Vikner (Yiddish), Valentina Bianchi (Italian), Ellen Brandner, Gisbet Fanselow,

Josef Bayer, Markus Benzinger, Philipp Conzett, Ren Schiering (German and German vari-

eties), Marit Julien (Norwegian), and Ulf Teleman and other friends and colleagues in Lund:

Camilla Thurn, Cecilia Falk, Christer Platzack, David Hkansson, Henrik Rosenkvist, Martin

Ringmar, and Verner Egerland (Swedish and Swedish varieties). A preliminary version of this

work was published in Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax 76: 93133 (Accusative and the

Nom/Acc alternation in Germanic).

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 12:01 F: LA9701.tex / p.3 (203-256)

The Nom/Acc alternation in Germanic :,

as simply the rst, independent case, case1, and Acc as the second case, case2,

dependent on Nom being present in the structure. Section 4 argues that this mor-

phological understanding enables us to analyze the English type of predicative

Acc as involving an extension of the general Nom/Acc distinction between argu-

ments to DPs. In the concluding Section 5, I suggest, on the basis of the presented

facts and analysis, that we need to abandon the view that morpho(phono)logy is a

straightforward reection of syntax. Rather, we must see morphology and syntax

as distinct languages or codes, mutally understandable but foreign to each other.

That is, morphology does not mirror or show syntax, it translates it into its own

language, which is radically different from the language of Narrow Syntax (in

the sense of Chomsky 2000 and subsequent works).

i. The distribution of Nom/Acc across the Germanic languages

In this section, I will describe the distribution of accusative case and how it in-

teracts with nominative case in the Germanic languages, mainly the standard

ones. Three major domains will be considered. In 2.1, I discuss the relational or

structural cases in the sense of Burzio (1986) and the scope of his famous gen-

eralization. In 2.2, I discuss argumental and adverbial accusatives that do not fall

under BG, above all certain Icelandic accusative subjects that have sometimes been

considered to be mysterious and a major challenge to BG. Finally, in Section 2.3, I

describe the Germanic predicative Nom/Acc variation.

Sections 2.1 and 2.3 lay the foundations for the discussion in later sections,

whereas Section 2.2 is more of an intermezzo, a long detour I have been forced to

make in order to be able to later proceed on the main road, so to speak. Many of

the accusatives discussed in 2.2 are problematic and interesting, but those readers

who are only interested in the predicative Nom/Acc variation might opt for taking

a bypass more or less directly from Section 2.1 to Section 2.3.

The Germanic languages divide into (relatively) case-rich and case-poor lan-

guages, the former having (at least some) case-marking of full NPs, whereas the

latter have Nom/Acc marking of only pronouns. In addition, the case-rich lan-

guages have morphological dative and genitive case (to a varying extent).

Case-rich: Icelandic, Faroese, German, Yiddish

Case-poor: Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, North Frisian, English, West

Frisian, Dutch, Afrikaans

Many of the Germanic languages show considerable dialectal variation with re-

spect to the distribution of nominative and accusative case. Thus, some Swedish

and Norwegian varieties have partly neutralized the Nom/Acc distinction (see Ek-

lund 1982; Holmberg 1986), while other Swedish and Norwegian varieties have

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 12:01 F: LA9701.tex / p.4 (256-315)

:o Halldr rmann Sigursson

retained even dative case (Reinhammer 1973), some German varieties have some

instances of accusative instead of the general German type of nominative predica-

tive DPs, and so on. Also, many varieties that are often referred to as dialects are

more properly regarded as separate languages, from a linguistic point of view, in-

cluding for instance the Swedish lvdalsmlet (see Levander 1909) and the Ger-

man Cimbrian in northernmost Italy (see Tyroller 2003). I will however largely

limit the present study to the 12 above listed standard languages, only mentioning

other varieties occasionally.

i.: Germanic relational case-marking

All the standard Germanic languages show the core properties of accusative sys-

tems, assigning nominative to (non-quirky) subjects and accusative to most ob-

jects. This is illustrated below for three of the languages:

(2) a. She(/*Her) had seen me(/*I). English nom . . . acc

b. Hun(/*Hende) havde set mig(/*jeg). Danish nom . . . acc

c. Hn(/*Hana) hafi s mig(/*g). Icelandic nom . . . acc

A basic (and a generally known) fact about the standard Germanic languages is

that they all adhere to Burzios Generalization. The nontechnical version of BG is

as follows (Burzio 1986: 178; for exceptions, see below and, e.g., Burzio 2000):

(3) All and only the verbs that can assign a -role to the subject can assign

accusative case to an object

An alternative simple formulation of this correlation is given in (4):

(4) Relational Acc is possible only if its predicate takes an additional, external

argument

As I have argued in earlier work, however, the true generalization is evidently

not about the relation between the external role and the internal case, but be-

tween the cases themselves, nominative versus accusative. I have referred to this

as The Sibling Correlation (in e.g. Sigursson 2003: 249, 258), formulating it

as follows:

(5) (acc nom) & (nom acc)

In other words, a relational (structural) accusative is possible only in the presence

of a nominative, whereas the opposite does not hold true, i.e. the nominative is

the rst or the independent case (an only child or an older sibling, as it were). A

similar or a related understanding has been argued for by others, most successfully

by Yip et al. (1987), but also by, e.g., Haider (1984, 2000), Zaenen et al. (1985), and

Maling (1993). Importantly, however, the Sibling Correlation only makes sense if

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 12:01 F: LA9701.tex / p.5 (315-382)

The Nom/Acc alternation in Germanic :

it applies generally, in non-nite as well as in nite clauses (see Sigursson 1989,

1991). I will discuss the nature of the Sibling Correlation in Section 3.

In accordance with BG or SC, unaccusative (or ergative) verbs like arrive,

unergative verbs like run and raising verbs like seem take nominative rather than

accusative subjects in nominative-accusative languages like English. This is illus-

trated by the following examples.

(6) a. She arrived late. / *Her arrived late.

b. She ran home. / *Her ran home.

c. She seemed to be shocked. / *Her seemed to be shocked.

More tellingly, an accusative object argument of a transitive verb turns up as

nominative subject in passive and unaccusative constructions:

(7) a. They red her.

b. She was red. / *Her was red.

(8) a. They drowned her.

b. She drowned. / *Her drowned.

These facts are well-known and have been widely studied and discussed (for a re-

cent detailed study of case-marking in English, see Quinn 2005a). As one would

expect, much the same facts are found in the other Germanic languages. This is il-

lustrated belowfor only transitive/passive pairs in German, Swedish and Icelandic,

respectively:

(9) a. Sie

they

haben

have

ihn

him.acc

gewhlt.

chosen

They chose him.

b. Er

he.nom

wurde

was

gewhlt.

chosen

/

/

*Ihn wurde gewhlt.

*acc

(10) a. De

they

valde

chose

honom.

him.acc

b. Han

he.nom

valde-s.

chose-pass

/

/

*Honom valde-s.

*acc

He was chosen.

(11) a. eir

they

vldu

chose

hana.

her.acc

b. Hn

she.nom

var

was

valin.

chosen

/

/

*Hana var valin.

*acc

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 12:01 F: LA9701.tex / p.6 (382-441)

:8 Halldr rmann Sigursson

i.i Non-Burzionian accusatives

A priori, it is not clear why BG or SC should hold, that is, it is not obvious why the

subjects in the examples above cannot be accusative. It is appropriate to further

highlight this seemingly unexpected fact:

(12) a. *Her arrived late.

b. *Her ran home.

c. *Her seemed to be shocked.

d. *Her was red.

e. *Her drowned.

Why is this the case in not only the other Germanic languages but in accusative

languages (and accusative subsystems) in general? We shall return to this ques-

tion in Section 3. Irrespective of the answer, these facts illustrate a truly striking

generalization, and it is indeed proper that it has a name of its own.

As acknowledged by Burzio (1986, 2000), however, it is not the case that all

accusatives fall under his generalization. Adverbial accusatives in languages like

German and Icelandic are perhaps the most obvious case of Non-Burzionian

accusatives:

(13) a. Dann

then

regnete

rained

es

it

den

the.acc

ganzen

whole.acc

Tag

day

/

/

*der

*nom

ganze Tag.

Then, it rained all day.

b.

then

rigndi

rained

allan

all.acc

daginn

day.the.acc

/

/

*allur

*nom

dagurinn.

Then, it rained all day.

Accusative adverbial NPs most commonly have a temporal reading, as in these

examples, but local (path) readings also occur, as illustrated below for Icelandic:

(14) a. Hn

she

synti

swam

heilan

whole.acc

klmetra

kilometre.acc

/

/

*heill

*nom

klmetri.

b. Hann

he

gengur

walks

alltaf

always

smu

same.acc

lei

route.acc

/

/

*sama

*nom

lei.

As discussed by (Zaenen et al. 1985: 474475), path adverbials of this sort often

show up in the nominative in passives, thus behaving similarly as Burzionian ac-

cusatives.

1

In contrast to argumental accusatives, however, path accusatives may

also be retained in impersonal passives, that is, the Acc passive (?)a er/var gengi

essa smu lei til baka daginn eftir it is/was walked this same route.acc back the

:. In Finnish, this even applies to temporal adverbials (Maling 1993).

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 12:01 F: LA9701.tex / p.7 (441-496)

The Nom/Acc alternation in Germanic :

day after is fairly acceptable, whereas, e.g., *a er/var teikna essa smu lei it

is/was drawn this same route.acc is impossible.

2

Another type of Non-Burzioninan accusatives is accusative complements of

prepositions. As illustrated below for English, German, Swedish and Icelandic, in

that order, accusative prepositional complements are well-formed in the absence

of an external argument:

(15) a. There is much talking about him here.

b. Hier

here

wird

is

(*es)

(*it)

viel

much

ber

about

ihn

him.acc

gesprochen.

talked

c. Hr

here

talas

is-talked

(det)

(it)

mycket

much

om

about

henne.

her.acc

d. Hr

here

er

is

(*a)

(*it)

tala

talked

miki

much

um

about

hana.

3

her.acc

These types are not problematic for BG, as it is formulated specically for argu-

ments of verbs, but they illustrate that morphological accusatives can be used for

Non-Burzonian purposes, even in basically accusative systems.

On the other hand, quirky accusatives are unexpected under BG and SC.

Consider the Icelandic examples below:

(16) a. Mig

me.acc

vantar

lacks

peninga.

money.acc

I lack/need money.

b. Mig

me.acc

langar

longs

heim.

home

I want to go home.

c. Mig

me.acc

furar

surprises

in

essu.

this

Im surprised by this.

As seen, the accusatives in these exampels are well-formed irrespective of whether

their predicate takes an additional argument. That is, BG and SC would seem

to make a wrong prediction for these predicates (but see below for a different

interpretation).

i. This applies to my own grammar, which, as far as I can tell, is the standard variety in this re-

spect. In the so-called new passive variety, on the other hand, a er/var teikna essa smu

lei it is/was drawn this same route.acc would be grammatical (see, e.g., Maling & Sigur-

jnsdttir 2002).

. The d-example illustrates the well-known fact that the Icelandic expletive can only occur

clause-initially (Thrinsson 1979; see also Sigursson 2004a for a feature based approach to this

Clause Initial Constraint, CLIC).

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 12:01 F: LA9701.tex / p.8 (496-559)

io Halldr rmann Sigursson

Jnsson (1998: 35f.) lists almost 60 predicates that take an accusative sub-

ject in (standard) Icelandic. As demonstrated below, Faroese (Thrinsson et

al. 2004: 253f.) and German also have examples of this sort, albeit much less

frequently:

(17) a. Meg

me.acc

grunai

suspected

hetta.

this.acc

Faroese

I suspected this.

b. Mich

me.acc

hungert.

hungers

German

I am hungry.

The Germanconstruction is peripherical (see, e.g., Wunderlich 2003), and it seems

to be rapidly disappearing from Faroese as well (Eythrsson & Jnsson 2003). It is

also losing some ground in colloquial Icelandic, through so-called dative sickness,

whereby accusative experiencer subjects in examples like (16ac) are replaced with

datives (see Smith 1996 and the references there).

Icelandic has a second type of quirky accusative subjects, where the subject is

not an experiencer but a theme or a patient, as illustrated below(Zaenen & Maling

1984 and many since):

(18) a. Okkur

us.acc

rak

drove

a

to

landi.

land

We drifted ashore.

(drove = got-driven)

b. Btinn

boat.the.acc

fyllti

lled

in

augabragi.

ash

The boat swamped immediately.

(lled = got-lled)

c. Mig

me.acc

tk

took

t.

out

I was swept overboard.

(took = got-taken)

d. Mennina

men.the.acc

bar

carried

a

towards

in

essu.

that

The men arrived then.

(carried = got-carried)

As we shall see shortly, this second, theme/patient construction has an uncon-

trolled process or fate reading. For convenience, we may thus refer to the ac-

cusatives in (16)(17) versus (18) as Psych Accusatives and Fate Accusatives,

respectively.

4

While Psych Accusatives tend to get replaced by datives, Fate Ac-

cusatives often give way to the nominative in (mainly) colloquial Icelandic (see

|. As pointed out to me by Kjartan Ottosson, the notion fate may not be entirely satisfactory

here. The most common type of these predicates typically involves the natural forces as the

source or the hidden agent of the event (as discussed in Ottosson 1988). However, this does

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 12:01 F: LA9701.tex / p.9 (559-618)

The Nom/Acc alternation in Germanic i:

Eythrsson 2000), in which case they behave like ordinary unaccusatives in the

language (see below).

As discussed by Haider (2001) and Kainhofer (2002), German also has Fate

Accusatives of a similar sort, as illustrated in (19) (ex. (7a) in Haider 2001: 6):

(19) Oft

often

treibt

drives

es

it

ihn

him.acc

ins

into-the

Gasthaus.

bar

He often drifts into the bar.

However, the German construction has an expletive, which perhaps or even plau-

sibly may be analyzed as carrying nominative case.

5

An expletive is excluded in the

Icelandic construction:

(20) a. Mann

one.acc

hrekur

drives

stundum

sometimes

af

off

lei.

track

Sometimes one loses ones track/gets carried away.

b. *a

it

hrekur

drives

mann

one.acc

stundum

sometimes

af

off

lei.

track

Thus, the Icelandic construction differs from the German one. However, Icelandic

has another construction that is to an extent similar to the German construc-

tion. This is the Impersonal Modal Construction, IMC, discussed in Sigursson

(1989: 163ff.), with an arbitrary external role and an optional expletive (the expli-

tive is generally only optional in Icelandic, see Thrinsson 1979). IMC is exem-

plied in (21); as suggested by the postverbal position of the accusatives, they are

regular objects and not quirky subjects (in contrast to the quirky accusatives in

(16), (18) and (20)):

(21) a. a

it

has

a

to

byggja

build

hsi

house.the.acc

hr.

here

They are going to build the house here.

b. a

it

arf

needs

a

to

astoa

assist

hana.

her.acc

One needs to assist her.

c. Hr

here

m

may

ekki

not

reykja

smoke

vindla.

cigars.acc

One may not smoke cigars here.

not extend to all examples of this sort, for instance (18d) and (20) below. I therefore take the

liberty of using the notion fate as a cover term for forces that are not in human power.

,. This might extend to the new passive in Icelandic (type It was hit me.acc). I will not dis-

cuss this here, but see, e.g., Sigursson (1989: 355f.), Sigurjnsdttir & Maling (2001), Maling &

Sigurjnsdttir (2002).

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 12:01 F: LA9701.tex / p.10 (618-769)

ii Halldr rmann Sigursson

Possibly, however, both IMC and the German construction throw a light on the

origin of the Icelandic Fate Accusative, that is, it may have grown out of a similar

transitive construction, with an unexpressed fate subject, as it were.

As discussed by Zaenen & Maling (1984) and by Sigursson (1989), ordinary

unaccusatives have similar properties in Icelandic as in related languages, show-

ing the familiar Acc-to-Nom conversion when compared to homophonous or

related transitives, much like passives. Consider the following transitive-passive-

unaccusative triple:

(22) a. Hn stkkai garinn.

she enlarged garden.the.acc

Transitive: Nom-Acc

b. Garurinn var stkkaur.

garden.the.nom was enlarged

Passive: Nom

c. Garurinn stkkai.

garden.the.nom enlarged

Unaccusative: Nom

In contrast, Fate Accusative predicates, like the ones in (18), show an unexpected

and (what seems to be) a cross-linguistically very rare behavior, in taking an

unaccusative accusative, as it were:

(23) a. Hn fyllti btinn.

she lled boat.the.acc

Transitive: Nom-Acc

b. Bturinn var fylltur.

boat.the.nom was lled

Passive: Nom

c. Btinn fyllti.

boat.the.acc lled

Unaccusative: Acc!

In contrast, datives and genitives are regularly retained in both passives and unac-

cusatives:

6

(24) a. Hn seinkai ferinni.

she delayed journey.the.dat

Transitive: Nom-Dat

b. Ferinni var seinka.

journey.the.dat was delayed

Passive: Dat

c. Ferinni seinkai.

journey.the.dat delayed

Unaccusative: Dat

On a lexical approach to quirky and inherent case-marking, we would seem to be

forced to analyze the accusative in (23c) (and the ones in (18)) as lexical, that is,

as selected by an quirky case requiring feature or property of the predicate (see the

discussion in Sigursson 1989: 280ff.). As seen in (23b), however, this accusative

o. As opposed to nominalizations and the so-called middle -st construction (see Zaenen &

Maling 1984 and many since, e.g., Svenonius 2005).

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 12:01 F: LA9701.tex / p.11 (769-839)

The Nom/Acc alternation in Germanic i

is not retained in the passive, instead undergoing the Nom-to-Acc conversion reg-

ularly seen for ordinary relational, non-inherent accusatives, as in (22b). That is,

what would seem to be one and the same accusative shows paradoxical behavior.

We may refer to this state of affairs as the Fate Accusative Puzzle. As we shall

see soon, however, the puzzle is in a sense not real, as the unaccusative accusative

is arguably not the same accusative as the transitive one.

As recently discussed by McFadden (2004), McIntyre (2005) and Svenonius

(2005), there are reasons to believe that the inherent cases are in fact structurally

matched against syntactic heads or features rather than lexically licensed.

7

In this

vein, Svenonius (2005) argues for a structural solution to the Fate Accusative Puz-

zle, suggesting that the predicates in question have a cause component but only

an optional voice, in the sense of Kratzer (1996) and Pylkknen (1999) where

voice is the head that licenses agent. In addition, Svenonius (2005) suggests that

cause is implicated in the licensing of accusative case, and is absent from normal

unaccusatives. That is, predicates are varyingly complex, transitives having both

voice and cause, Fate Accusative predicates or accusative unaccusatives having

only cause, and regular unaccusatives having neither:

8

(25) a. [

VoicP

DP

nom

voic [

CausP

caus [

VP

V DP

acc

]]] Transitive Nom-Acc

b. [

CausP

caus [

VP

V DP

acc

]] Acc unaccusatives

c. [

VP

V DP

nom

] Nom unaccusatives

Dative taking unaccusatives, like seinka delay in (24c), also have the cause com-

ponent plus a special dative or dat feature, necessary for the assignment of da-

. Thus, as has been observed in the literature every now and then, there is generally no xed

linking between lexical roots and specic cases, as illustrated by numerous minimal pairs like

the following one (involving various types of predicates):

(i) a. Veri

weather.the.nom

er

is

kalt.

cold

b. Mr

me.dat

er

is

kalt.

cold

Im freezing.

(ii) a. Hsi

house.the.nom

var

was

loka.

closed

The house was (in the state of being) closed.

b. Hsinu

house.the.dat

var

was

loka.

closed

The house was (in the process of being) closed (by someone).

8. Svenonius assumes a slightly more complex analysis (where active versus passive or act and

pass play a crucial role), but the presentation in (25) is sufciently detailed for our purposes.

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 12:01 F: LA9701.tex / p.12 (839-902)

i| Halldr rmann Sigursson

tive case (ibid). The transitive and the dative unaccusative in (24a, c) thus have

roughly the following structures:

(26) a. [

VoicP

DP

nom

voic[

CausP

caus[

DatP

dat[

VP

VDP

dat

]]] Transitive Nom-Dat

b. [

CausP

caus [

DatP

dat [

VP

V DP

dat

]]] Dat unaccusatives

Icelandic has many kinds of datives (Bardal 2001; Maling 2002a, 2002b; Jns-

son 2003; Sigursson 2003: 230ff.), so we must understand dat as a shorthand for

an array of syntactic features (heads) or feature combinations, each such feature

or feature combination leading to dative case-marking in Icelandic morphology.

9

With that modication, it seems to me that Svenonius has developedan interesting

approach to many of the numerous facts known from the voluminous literature

on Icelandic case. However, while a structural approach to the inherent cases is

promising, such an approach to the relational, so-called structural cases (Burzio-

nian Nom/Acc) is fundamentally mistaken, I believe, contradictory as that may

seem (see also Sigursson 2003, 2006). I will return to the issue in Section 3.

As mentioned above, the peculiar accusative unaccusative construction in

Icelandic has a special uncontrolled process semantics, a get-passive fate reading

of a sort, hence the term Fate Accusative. Consider (18) = (27):

(27) a. Okkur

us.acc

rak

drove

a

to

landi.

land

We drifted ashore.

(drove = got-driven)

b. Btinn

boat.the.acc

fyllti

lled

in

augabragi.

ash

The boat swamped immediately.

(lled = got-lled)

c. Mig

me.acc

tk

took

t.

out

I was swept overboard.

(took = got-taken)

d. Mennina

men.the.acc

bar

carried

a

towards

in

essu.

that

The men arrived then.

(carried = got-carried)

Importantly, this fate reading is not shared by the transitive or passive counterparts

to these (or other Fate Accusative) predicates (as already pointed out by Ottosson

1988: 148). Thus, Icelandic we lled the boat and the boat was lled has much

the same expected readings as English We lled the boat and The boat was lled,

that is, it means that the boat was deliberately lled in some usual, expected man-

ner, with sh or some cargo. Icelandic the boat lled, in contrast, has only one

very specic meaning, namely that the boat unexpectedly and dangerously got

. The same features are arguably present in the syntax of languages, such as English, that keep

quiet about them in their morphology (cf. Sigursson 2003, 2004d).

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 12:01 F: LA9701.tex / p.13 (902-960)

The Nom/Acc alternation in Germanic i,

lled with water, i.e. that it swamped. Similarly, Icelandic Mig tk t in (27c), lit-

erally me took out, cannot possibly mean that somebody took me out. It has only

one, very specic meaning, the fate reading that I accidentally swept aboard. In all

cases of this sort, the transitive and passive versions have much the same general,

broad semantics as in English and other related languages, whereas accusative un-

accusatives always have a narrow, semi-idiomatic fate meaning, absent from the

transitive and the passive.

This important fact has not been generally noticed or highlighted, so one com-

monly sees pairs like the following in the literature (here taken from Sigursson

1989: 216, but see also similar examples in e.g. Zaenen & Maling 1984; Jnsson

1998; Svenonius 2005):

(28) a. Btinn

boat.the.acc

rak

drove

on

land.

land

The boat drifted ashore.

b. Stormurinn

storm.the.nom

rak

drove

btinn

boat.the.acc

on

land.

land

This description is however misleading. As pointed out already by Ottoson

(1988: 147f.), transitive clauses like (28a) are semantically anomalous, since tran-

sitive verbs like reka drive usually require an animate agent. The same holds for

other apparent pairs or sets of transtives/passives and accusative unacusatives, as

illustrated below for fylla ll:

(29) a. Btinn

boat.the.acc

fyllti

lled

(af

(with

sj).

sea)

The boat swamped.

b.

?

Sjrinn

sea.the.nom

fyllti

lled

btinn.

boat.the.acc

(30) a. Vi

we.nom

fylltum

lled

btinn.

boat.the.acc

We lled the boat (with cargo, sh, etc.).

b. Bturinn

boat.the.nom

var

was

fylltur.

lled

The boat was lled (with cargo, sh, etc.).

Thus, the accusative unaccusatives require a special fate or uncontrolled process

feature to be present or active in their clausal structure. Call this feature simply

fate. There is no doubt, as we have seen, that this feature is precluded in related

transitives and passives, and the natural interpretation of that fact is that fate is a

voice feature of a sort, blocking or turning off the usual voice feature that other-

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 12:01 F: LA9701.tex / p.14 (960-1004)

io Halldr rmann Sigursson

wise introduces agent in both transitives and passives.

10

As Ottosson (1988: 148)

puts it, Fate Accusatives occur in a construction that stands outside the regu-

lar voice system. That is, the nature of Fate Accusatives is quite different from

that of normal relational (not semantically linked) accusatives, and hence the Fate

Accusative Puzzle is not real.

The fate feature is largely (but not entirely) specic for the accusative un-

accusatives, that is, it is not generally active in structures with either regular un-

accusatives or dative taking unaccusatives. This is illustrated for the dative taking

ljka nish, end (discussed in, e.g., Sigursson 1989 and Svenonius 2005):

(31) a. Hn

she.nom

lauk

nished

sgunni.

story.the.dat

She nished the story.

b. Sgunni

story.the.dat

lauk.

nished

The story ended/came to an end.

The transitive means end/nish something, and the unaccusative also has the gen-

eral core meaning end, without any special reading being added. While Fate Ac-

cusative predicates yield information about the power (fate/natural forces) causing

the event, such semantically narrowing or specifying information is absent from

many or most other unaccusative predicates. It is of course logically possible that

an event expressed by predictes like ljka nish, end, seinka delay in (24) and

stkka enlarge in (22) can be due to fate or natural forces, but this reading is not

forced for these predicates, in contrast with Fate Accusative predicates.

In sum, there is no doubt that Fate Accusatives relate to semantics of a rather

special sort. However, this does not alter the fact that these peculiar accusatives are

like Psych Accusatives in that they do not comply with BG or the Sibling Correla-

tion. Restaurant Talk Accusatives, recently discussed by Wiese and Maling (2005),

on the other hand, can be anlyzed as involving deletion, as sketched below for

German and Icelandic, respectively:

11

:o. An issue of general theoretical interest is whether inactive features are syntactically absent,

or present but default or not activated. I assume the latter (following Cinque 1999: 127ff.; for a

general discussion, see also Sigursson 2004d).

::. Alternatively, one can assume silent functional categories in examples of this sort, including

the subject number and person, a modal head commonly expressed by verbs meaning want and

a silent main predicate commonly expressed by verbs meaning get. Under such an approach

(tallying with the approach to morphosyntactic silence argued for in Sigursson 2004d), the

problem of recoverability does not arise.

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 12:01 F: LA9701.tex / p.15 (1004-1089)

The Nom/Acc alternation in Germanic i

(32) a. Ich

I.nom

mchte

would-like

Einen

a

Kaffee

coffee.acc

bekommen,

get,

bitte.

please

One coffee, please

b. g

I.nom

vil

want

f

get

Tvo

two

stra

large

bjra,

beers.acc,

takk.

please

Similarly, accusatives in PRO innitives are unproblematic if nominative is active

in such innitives (as argued in Sigursson 1989, 1991):

(33) a. Mir

me.dat

graut

dreads

[PRO

PRO

den

the

Brief

letter.acc

zu

to

schreiben].

write

German

I nd it dreadful to write the letter.

b. Mr

me.dat

leiist

bores

[a

to

PRO

PRO

lesa

read

bkina].

book.the.acc

Icelandic

I nd it boring to read the book.

Icelandic has many predicates that take a dative subject and a nominative object

(Thrinsson 1979; Zaenen et al. 1985; Sigursson 1989, 1996, and many others),

and German has some similar Dat-Nompredicates (usually taken to have different

properties as regards subjecthood versus objecthood, but see Eythrsson & Bar-

dal 2005 and Bardal 2006 for a different view). In contrast, some related and/or

similar predicates in Faroese are Dat-Acc predicates, as illustrated in the examples

below (from Thrinsson et al. 2004: 255ff.):

(34) a. Mr

me.dat

lkar

likes

hana

her.acc

vl.

well

I like her.

b. Henni

her.dat

vantar

lacks

ga

good

orabk.

dictionary.acc

She needs a good dictionary.

The Icelandic equivalent of (34b) can in fact also be heard in substandard Ice-

landic. Conversely, Faroese also has some Dat-Nom predicates.

In Sigursson (2003), I argued that accusatives in examples of this sort are

relational, the structures in question involving an invisible nominative, triggering

or licensing the accusative (in accordance with the Sibling Correlation; for related

ideas see Haider 2001, but for a different approach, see, e.g., Woolford 2003). This

would seem to get support from the historical development in English in general

(Allen 1996) and partly in Faroese, where numerous predicates have altered their

case frames in the following manner:

(35) Dat

i

-Nom

j

> Dat

i

-Acc

j

(or Oblique

i

-Oblique

j

) > Nom

i

Acc

j

Alternatively, one might want to suggest that the accusative in Faroese Dat-Acc

constructions is licensed by the external dative or that it is some sort of a default

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 12:01 F: LA9701.tex / p.16 (1089-1148)

i8 Halldr rmann Sigursson

case, but that would seem to raise even more difcult problems and questions

than the invisible nominative case approach, most simply the question of why the

Faroese subject dative should license or allow object accusative any more than ex-

ternal datives in e.g. standard Icelandic, German and Old English. Also, invoking

the notion of default case amounts to giving up any hope of an insightful ac-

count. If Faroese resorts to default case in its Dat-Acc constructions, the question

arises why it does not in e.g. predicative constructions (see the next subsection).

Moreover, the change Dat

i

-Acc

j

> Nom

i

-Acc

j

would involve two changes on the

default case approach (inherent-default > relational-relational), whereas it involves

only one change on the relational case approach (inherent+relational-relational >

relational-relational). In addition, the accusative in the Faroese Dat-Acc pattern

seems to be like regular relational accusatives in not being semantically linked,

unlike both Psych Accusatives and Fate Accusatives.

Regardless of how we account for the exceptional Dat-Acc pattern in Faroese,

it is clearly unexpected under any straightforward morphological understand-

ing of Burzios Generalization (BG) and the Sibling Correlation (SC), like Psych

Accusatives and Fate Accusatives. Yet another type of unexpected argumental ac-

cusatives is found in a peculiar (and lexically a very limited) raising construction

in Icelandic (discussed in Sigursson 1989, e.g., 218f.), where accusative is retained

or fossilized, in contrast to, e.g., both German and English:

(36) a. laf/*lafur

Olaf.acc/*nom

var

was

hvergi

nowhere

a

to

nna

nd

__.

b. Er/*Ihn

he/*him

war

was

nirgends

nohwere

zu

to

nden

nd

__.

c. He/*Him was nowhere to be found __.

As mentioned above, adverbial and prepositional accusatives are not really prob-

lematic for BG or SC. On the other hand, all the argumental accusatives that are

well-formed in the absense of an external nominative argument are unexpected

under BG/SC:

Psych Accusatives in Icelandic and to an extent in German and Faroese

Fate Accusatives in Icelandic (and possibly in German varieties, depending on

whether or not the expletive carries nominative case)

The fossilized accusative in Icelandic examples like (36a) (perhaps only a

subtype of the Fate Accusative)

The accusative in Faroese Dat-Acc constructions

JB[v.20020404] Prn:25/09/2006; 12:01 F: LA9701.tex / p.17 (1148-1193)

The Nom/Acc alternation in Germanic i

Moreover, English allows (subject and) object accusatives in gerunds like the fol-

lowing ones (see e.g. Quinn 2005a: Section 8.6), where there is no visible well-

formed nominative:

12

(37) a. I was embarrassed [by him seeing me there].

b. [His accusing me] surprised me greatly.

c. [Him seeing me there] was unfortunate.

d. *[He seeing me there] embarrassed me.

There seems no doubt that the object accusative in examples of this sort is a regular

accusative, much as in subjectless gerunds and PRO innitives:

(38) a. Seeing me there suprised him.

b. To see me there surprised him.

On the relational view of the so-called structural cases, the object accusative

in all these cases is licensed by an active nominative case feature, even though