Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Mini-Clinical Evaluation Exercise

Uploaded by

Fernando SalgadoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Mini-Clinical Evaluation Exercise

Uploaded by

Fernando SalgadoCopyright:

Available Formats

The Mini Clinical

Evaluation Exercise

(mini-CEX)

John J. Norcini, Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and

Research (FAIMER

)

INTRODUCTION

T

he mini Clinical Evaluation

Exercise or mini-CEX is a

method for simultaneously

assessing the clinical skills of

trainees and offering them feed-

back on their performance. It is a

simple modication of the tradi-

tional bedside oral examination

and because of that, it relies on

the use of real patients and the

judgments of skilled clinician

educators. This article describes

the mini-CEX, recounts how it was

developed, and then illustrates its

use in the Modernising Medical

Careers (MMC) Foundation Pro-

gramme Assessment.

BACKGROUND

How the mini-CEX works

In the mini-CEX, a single faculty

member observes the trainee

interact with a patient in any of a

variety of settings including the

hospital, outpatient clinic, and

A&E. The trainee conducts a

focused history and physical

examination and after the

encounter provides a diagnosis

and treatment plan. The faculty

member scores the performance

using a structured document and

then provides educational feed-

back. The encounters are intended

to be relatively short, about 15

minutes, and to occur as a routine

part of the training programme.

Each trainee should be evaluated

on several different occasions by

different faculty examiners.

Development of the mini-CEX

For the rst four decades of its

existence, the American Board of

Internal Medicine administered a

traditional bedside oral examina-

tion as part of its certication

process. By 1972, the problems of

assessing thousands of doctors

annually had become so great

that the oral examination was

discontinued. In its place, the

Board asked training programme

directors to assess the clinical

competence of candidates for

certication and recommended

the use of a clinical evaluation

exercise, or CEX, for trainees in

their rst postgraduate year.

The CEX was based on the

bedside oral examination that was

part of the certication process. A

single faculty member evaluated

the trainee as he or she performed

a complete history and physical

examination on a pre-selected

patient in the hospital. Trainees

were then expected to reach diag-

nostic and therapeutic conclu-

sions, present their ndings, and

produce a written report of the

The CEX

evaluates the

trainees

performance

with a real

patient

Practical

Assessment

June 2005 | Volume 2 | No 1| www.theclinicalteacher.com THE CLINICAL TEACHER 25

patient. The faculty member then

assessed the trainees performance

along several dimensions. The CEX

took about two hours and by the

early 1990s the vast majority of

rst year internal medicine train-

ees in the United States were being

assessed by this method.

The CEX has at least three

important strengths.

It evaluates the trainees per-

formance with a real patient.

In medical school, the Objec-

tive Structured Clinical Exam-

ination (OSCE) is often used

and it does an excellent job of

assessing clinical skills. As

trainees approach entry to

practice, however, their edu-

cation and assessment needs

to be based on performance

with real patients who exhibit

the full range of conditions

seen in the clinical setting.

The trainee is observed by a

skilled clinician-educator who

both assesses the performance

and provides educational

feedback. This enhances the

validity of the results and

ensures that the trainee

receives the type of

constructive criticism that

should result in a reduction of

errors and an improvement in

quality of care.

The CEX presents trainees with

a complete and realistic clin-

ical challenge. They have to get

all of the relevant information

from the patient, structure the

problem, synthesise their nd-

ings, create a management

plan, and communicate this in

both oral and written form.

Despite its strengths, a grow-

ing research literature through

the 1980s and 1990s showed that

the results of CEX were not likely

to generalise very far beyond the

single encounter that was ob-

served. This conclusion was based

on numerous studies of the

assessment of doctors.

The research showed that

trainees performances with

one patient were not a very

good predictor of their per-

formances with other patients.

Consequently, they needed to

be observed on different

occasions with different

patients before drawing

The CEX

presents

trainees with a

complete and

realistic clinical

challenge

26 THE CLINICAL TEACHER June 2005 | Volume 2 | No 1| www.theclinicalteacher.com

reliable conclusions about

their competence. Observing

each trainee with several

patients was also desirable

from an educational perspec-

tive, since different patients

require different skills from

trainees and this signicantly

broadens the range and rich-

ness of feedback they receive.

The research showed that the

assessors did not agree with

each other even when they

were observing exactly the

same performance. Training of

assessors is helpful to some

degree but much larger

improvements in the reliabil-

ity and validity of the ratings

was achieved by including

different faculty members in

the overall assessment of each

trainee. This was also useful

from the perspective of edu-

cation, since trainees received

feedback from different asses-

sors, each with their own

specialties, strengths, and

perspectives.

In terms of the method itself,

the CEX focused on the trai-

nees ability to be thorough

with a single new patient in a

hospital setting that is unin-

uenced by time constraints.

In contrast, different patients

pose different challenges and

the tasks or competencies

required of doctors vary con-

siderably depending on the

setting in which care is ren-

dered. Further, most patient

encounters are much shorter

than two hours so the CEX

does not assess the trainees

ability to focus and prioritise

diagnosis and management.

The mini-CEX is a response to

some of the shortcomings of the

CEX and it is based on the educa-

tional interactions faculty rou-

tinely have with trainees during

teaching rounds. As in the CEX, one

faculty member observes a trainee-

patient encounter. However, the

encounter is focused, lasts roughly

15 minutes, and several encoun-

ters are included in the overall

assessment of a trainee. The

encounters will portray a broader

range of challenges because they

can occur in a variety of settings

(i.e., ambulatory/out-patient,

The assessor

and trainee

must agree to

and record an

educational

plan of action

June 2005 | Volume 2 | No 1| www.theclinicalteacher.com THE CLINICAL TEACHER 27

primary care, A&E department,

and inpatient). The fact that

several encounters are observed

increases the quality of both the

assessment and the educational

feedback. It also offers the oppor-

tunity to include different faculty

members in any one trainees

evaluation.

Foundation Programme

Assessment

The mini-CEX has been used in a

variety of countries, specialties,

clinical settings, and levels of

training. It is currently being

evaluated as part of the National

Health Services Modernising

Medical Careers Foundation

Assessment Programme and its

use in this programme illustrates

many of the issues involved in

implementing the mini-CEX.

What does the mini-CEX assess?

Consistent with the quality

improvement model used in the

Foundation Programme, the mini-

CEX is intended to identify areas

of strength and weakness. The

competencies assessed and

descriptions of them can be seen

in Table 1.

What must the trainees do?

Over the period of a year, the

trainees must get at least six

different doctors (SpRs, Specialist

Associate/Staff Grades, consult-

ants, GPs) to assess them towards

the end of their rotation through

different posts. For example,

trainees could ask a doctor to

observe them with the last

patient on a ward round or the

next patient coming to the GP

surgery. They should be perform-

ing a task routinely expected of

them (e.g. clerking a new patient)

and the six encounters must cover

the main areas of the curriculum

(http://www.mmc.nhs.uk/

curriculum). After the encounter,

trainees keep one copy of the

structured evaluation form for

their portfolios, give one to their

educational supervisor, and one

goes to the Trust Foundation

Coordinator for forwarding to the

central administrative centre.

What must the assessors do?

The assessor must ensure that the

patient is aware of the mini-CEX

and is typical of the trainees

workload. After observing the

encounter, the assessor completes

the form in Table 1. As can be

seen, all of the competencies are

rated on a six-point scale where 1

and 2 are below expectations, 3

is borderline, 4 is meets expec-

tations, and 5 and 6 are above

expectations for the end of the

second foundation year.

The assessor is also required

to give the trainee feedback

immediately following the

assessment. He or she must note

particular strengths and sugges-

tions for development on the

form. In addition, the assessor

and trainee must agree to and

record an educational plan of

action. This feedback structure

is in line with evidence-based

good practice.

The assessor is also respon-

sible for recording information

about the encounter itself. This

information ensures that there is

sufcient coverage of the curri-

culum, provides some notion of

the nature and complexity of the

patients problems, and provides

information on mini-CEX know-

ledge and experience. There is

also research indicating that some

of these factors are related to

performance on the mini-CEX. For

example, previous work has shown

that assessors tend to overcom-

pensate by giving higher grades

when the patients problems are

more complicated.

What guidance is given?

Written guidance is given to both

the trainees and the assessors. A

description of the Foundation

Assessment Programme can be

found at http://www.mmc.

nhs.uk/. Trainees are provided

with a description of the mini-

CEX, advised about whom they

should invite to be the assessor,

what they should be assessed

doing, when it should be used,

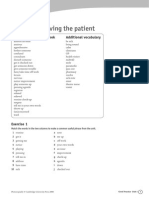

Table 1

Competence Descriptor of a Satisfactory Trainee

History Taking Facilitates patients telling of story, effectively

uses appropriate questions to obtain accurate,

adequate information, responds appropriately to

verbal and non-verbal cues.

Physical Exam Follows efcient, logical sequence; examination

appropriate to clinical problem, explains to

patient; sensitive to patients comfort, modesty.

Professionalism Shows respect, compassion, empathy, establishes

trust; Attends to patients needs of comfort,

respect, condentiality. Behaves in an ethical

manner, awareness of relevant legal frameworks.

Aware of limitations.

Clinical Judgment Makes appropriate diagnosis and formulates a

suitable management plan. Selectively orders/

performs appropriate diagnostic studies,

considers risks, benets.

Communication skill Explores patients perspective, jargon free, open

and honest, empathetic, agrees management

plan/therapy with patient.

Organisation/Efciency Prioritises; is timely. Succinct. Summarises.

Overall Clinical Care Demonstrates satisfactory clinical judgment,

synthesis, caring, effectiveness. Efciency,

appropriate use of resources, balances risks and

benets, awareness of own limitations.

Routine

discussion

among faculty

will improve the

quality of the

assessments

28 THE CLINICAL TEACHER June 2005 | Volume 2 | No 1| www.theclinicalteacher.com

and how it should work. They are

given copies of the forms that

need to be completed and

responsibility for having them

done in a timely fashion.

Assessors are also given writ-

ten guidance that contains a

description of the mini-CEX and

how it works. They receive infor-

mation about the development of

the method, its purpose, and its

place in the overall Foundation

programme. The competences to

be assessed are listed and des-

cribed for the satisfactory trainee

Mini-Clinical Evaluation Exercise (CEX). Courtesy of Department of Health, England.

June 2005 | Volume 2 | No 1| www.theclinicalteacher.com THE CLINICAL TEACHER 29

and special stress is placed on the

feedback to be given to trainees.

Details of the administration are

also provided.

Although exhaustive training

of the assessors is unlikely to be

productive, a workshop to start

the process and routine discus-

sion among faculty will improve

the quality of the assessments

and the feedback. Evidence-based

training should focus on four

aspects of the process.

Reducing common errors (e.g.

being too severe or too

lenient)

Understanding the dimensions

being assessed and the

standard of assessment

Improving the accuracy of

ratings

Improving the detection and

recall of performance

A number of national training

days have been provided and

further training is planned.

What happens with the results?

Each of the rating forms is

returned to a central location and

the data are entered into the

computer. When six encounters

have been completed, the data

are collated for the whole year

and returned to the trainee via

his/her programme director. The

educational supervisor will dis-

cuss the feedback with the trai-

nee. In addition, the mini-CEX

results will be incorporated into

an overall assessment prole for

each trainee.

CONCLUSION

The mini-CEX is a way of simulta-

neously assessing the clinical

skills of trainees and offering

them feedback intended to en-

hance their future performance.

Its validity and reliability derives

from the fact that trainees are

observed while engaged with a

series of real patients in different

practice setting and judgments

about the quality of those

encounters are made by skilled

educator-clinicians. Its educa-

tional effect is based on a signi-

cant increase in the number of

occasions on which trainees are

directly observed with patients

and offered feedback on their

performance.

FURTHER READING

Norcini JJ, Blank LL, Arnold GK, Kimball

HR. The Mini-CEX (Clinical Evaluation

Exercise): A preliminary investigation.

Ann Intern Med 1995; 123: 79599.

Norcini JJ, Blank LL, Duffy FD, Fortna G.

The mini-CEX: A method for assessing

clinical skills. Ann Intern Med

2003;138:476481.

Day SC, Grosso LG, Norcini JJ, Blank LL,

Swanson DB, Horne MH. Residents per-

ceptions of evaluation procedures used

by their training program. J Gen Intern

Med 1990;5:421426.

Elstein AS, Shulman LS, Sprafka SA.

Medical problem solving: An analysis of

clinical reasoning. Cambridge, MA: Har-

vard University Press, 1978.

Noel GL, Herbers JE, Caplow MP, Cooper

GS, Pangaro LN, Harvey J. How well do

internal medicine faculty members

evaluate the clinical skills of residents?

Ann Intern Med 1992;117:757765.

Holmboe ES. The importance of faculty

observation of trainees clinical skills.

Acad Med 2004; 79: 1622.

Holmboe ES, Hawkins RE, Huot SJ. Direct

observation of competence training: a

randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern

Med 2004; 140: 87481.

Holmboe ES, Yepes M, Williams F, Hout

SJ. Feedback and the mini clinical eval-

uation exercise. J Gen Intern Med 2004;

19(5 Pt 2): 55861.

30 THE CLINICAL TEACHER June 2005 | Volume 2 | No 1| www.theclinicalteacher.com

You might also like

- The Ultimate Medical School Collection: Tips and advice for securing the best work experience, writing a peerless UCAS personal statement, & anticipating interview questions for any UK medical schoolFrom EverandThe Ultimate Medical School Collection: Tips and advice for securing the best work experience, writing a peerless UCAS personal statement, & anticipating interview questions for any UK medical schoolNo ratings yet

- Mini Clinical Examination (Mini-CEX)Document21 pagesMini Clinical Examination (Mini-CEX)Jeffrey Dyer100% (1)

- Exams NAC Guideline Rating ScaleDocument2 pagesExams NAC Guideline Rating ScaleM.Dalani100% (1)

- Anking Interview Questions You Will Be AskedDocument6 pagesAnking Interview Questions You Will Be AskedKevanNo ratings yet

- Step 1 USMLE ContentDocument9 pagesStep 1 USMLE ContentGeorge BestNo ratings yet

- Manuscript of Step 2 CsDocument8 pagesManuscript of Step 2 CsJason SteelNo ratings yet

- Usmle Step CKDocument10 pagesUsmle Step CKNitish SinhaNo ratings yet

- New Pathways Call To Action - Leadership ResponseDocument10 pagesNew Pathways Call To Action - Leadership Responseapi-582672055No ratings yet

- Medical Student Performance Evaluation For جيرخلا مسا ماعلاريدقتلا / وينوي) وأ (ربمسيد ةعفدلاDocument6 pagesMedical Student Performance Evaluation For جيرخلا مسا ماعلاريدقتلا / وينوي) وأ (ربمسيد ةعفدلاeolhc rezarfNo ratings yet

- Personal Statement Guide by Doctor Laska PDFDocument3 pagesPersonal Statement Guide by Doctor Laska PDFSteve JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Choosing A Medical Specialty Resource Guide 2Document141 pagesChoosing A Medical Specialty Resource Guide 2MohamedZeyadNo ratings yet

- Sample Personal Letter Ophthalmology 1Document1 pageSample Personal Letter Ophthalmology 1John Christian Mirasol RnNo ratings yet

- OsceDocument11 pagesOscedocali11No ratings yet

- Residencymanual 2015 2016 PDFDocument53 pagesResidencymanual 2015 2016 PDFcelecosibNo ratings yet

- Accruing LORsDocument7 pagesAccruing LORssamNo ratings yet

- Class of 2019 MSPE Noteworthy Characteristics QuestionnaireDocument23 pagesClass of 2019 MSPE Noteworthy Characteristics QuestionnaireAmir Ali100% (1)

- Sample MSPE - EditedDocument11 pagesSample MSPE - EditedGunjan KhuranaNo ratings yet

- OSCE Stations ChecklistDocument51 pagesOSCE Stations ChecklistAnonymous A0uofxhUNo ratings yet

- Psychiatry Guidebook 2022Document13 pagesPsychiatry Guidebook 2022Sarah MeskalNo ratings yet

- A Primer of Personal StatementsDocument14 pagesA Primer of Personal StatementsAli TotoNo ratings yet

- Case Report TemplateDocument3 pagesCase Report TemplateChairul Nurdin AzaliNo ratings yet

- CaRMS Guide: The Application ProcessDocument26 pagesCaRMS Guide: The Application Processbicodoc100% (1)

- CKD PocketGuideDocument2 pagesCKD PocketGuidelayzierainNo ratings yet

- Step 2 Cs Core CasesDocument39 pagesStep 2 Cs Core CasesjNo ratings yet

- MyERAS - Personal StatementsDocument2 pagesMyERAS - Personal StatementsDaniel GonzalezNo ratings yet

- EPP InterviewQuestions TipsDocument5 pagesEPP InterviewQuestions TipsAbdul HaziqNo ratings yet

- 99 Day Study Schedule For USMLE Step 1Document22 pages99 Day Study Schedule For USMLE Step 1Den IseNo ratings yet

- "Usmle Cs2Document27 pages"Usmle Cs2Drbee10No ratings yet

- OSCE Preparation TipsDocument18 pagesOSCE Preparation TipsMin Maw100% (1)

- LOR Guide For StudentsDocument2 pagesLOR Guide For StudentsHema LaughsalotNo ratings yet

- Iserson's Getting Into A Residency: A Guide For Medical StudentsDocument3 pagesIserson's Getting Into A Residency: A Guide For Medical StudentsRatnam hospital0% (3)

- Penile Catheterisation OSCE Mark SchemeDocument2 pagesPenile Catheterisation OSCE Mark Schemeabdisalan aliNo ratings yet

- Mental State Exam OSCE Mark SchemeDocument2 pagesMental State Exam OSCE Mark SchemeoluseyeNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Writing CVDocument1 pageGuidelines For Writing CVanwar933No ratings yet

- Residency Interview Advice, Tips, and QuestionsDocument3 pagesResidency Interview Advice, Tips, and QuestionsRoy WakninNo ratings yet

- "Dos and Don'Ts" of Residency InterviewingDocument35 pages"Dos and Don'Ts" of Residency InterviewingShashwat Singh PokharelNo ratings yet

- List of Programs - IM - Early DraftDocument285 pagesList of Programs - IM - Early DraftAbs Sarry100% (1)

- Crushing The Residency Interview 2017Document27 pagesCrushing The Residency Interview 2017FerasNo ratings yet

- GoodPractice WL U01ReceivingPatientDocument3 pagesGoodPractice WL U01ReceivingPatientReka Kutasi100% (1)

- OET Official Blog NotesDocument12 pagesOET Official Blog NotesMehmet Şevki UyanıkNo ratings yet

- 10 GP ConsultationsDocument4 pages10 GP ConsultationsDev KumarNo ratings yet

- Canadian Screening GuidelinesDocument8 pagesCanadian Screening GuidelinesaayceeNo ratings yet

- Homsi Amer Surgery Personal Statement FinalDocument1 pageHomsi Amer Surgery Personal Statement Finalamh2013No ratings yet

- Check Unit 556 December Digestive PDFDocument33 pagesCheck Unit 556 December Digestive PDFdragon66No ratings yet

- Review of SystemsDocument3 pagesReview of SystemsCarrboro Family Medicine100% (1)

- Plab2 Stations Topics New Old PDFDocument6 pagesPlab2 Stations Topics New Old PDFBeaulahNo ratings yet

- IVMS ICM-Communication Skills in Clinical Medicine-10-17 UpdatedDocument38 pagesIVMS ICM-Communication Skills in Clinical Medicine-10-17 UpdatedMarc Imhotep Cray, M.D.No ratings yet

- History Taking FormDocument2 pagesHistory Taking FormMaria Santiago100% (1)

- Gynaecology and Obstetrics PDFDocument50 pagesGynaecology and Obstetrics PDFabdulmoiz92No ratings yet

- PP Report SheetDocument2 pagesPP Report SheetTrina EagalNo ratings yet

- NSG 6340 Final Exam 1.........Document9 pagesNSG 6340 Final Exam 1.........Tom0% (1)

- My Step 2 CK Experience of 255Document2 pagesMy Step 2 CK Experience of 255bajariaa100% (3)

- Tubes, Lines, and Drains Basics: Harmacy Ompetency Ssessment EnterDocument11 pagesTubes, Lines, and Drains Basics: Harmacy Ompetency Ssessment EnterJeremy HamptonNo ratings yet

- Essential Cases for GP TraineesDocument3 pagesEssential Cases for GP TraineesTahir AliNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Initial Patient HistoryDocument11 pagesPediatric Initial Patient HistoryLinh TrịnhNo ratings yet

- Research Work Experience-GuideDocument5 pagesResearch Work Experience-GuideRaja Shakeel Mushtaque, M.D.100% (2)

- Tips for Effective Communication: A Vital Tool for Trust Development in HealthcareFrom EverandTips for Effective Communication: A Vital Tool for Trust Development in HealthcareNo ratings yet

- (65521479) AMEE Medical Education Guide No 24 Portfolios As A Method of Student AssessmentDocument19 pages(65521479) AMEE Medical Education Guide No 24 Portfolios As A Method of Student AssessmentFernando SalgadoNo ratings yet

- 2 FullDocument11 pages2 FullFernando SalgadoNo ratings yet

- 2 FullDocument11 pages2 FullFernando SalgadoNo ratings yet

- Xerox WorkCentre 3550 20130408152940Document1 pageXerox WorkCentre 3550 20130408152940Fernando SalgadoNo ratings yet

- Reflective Practice and Professional DevelopmentDocument3 pagesReflective Practice and Professional DevelopmentAnca Terzi MihailaNo ratings yet

- Unit 6.5 Strategic Marketing Level 6 15 Credits: Sample AssignmentDocument2 pagesUnit 6.5 Strategic Marketing Level 6 15 Credits: Sample AssignmentMozammel HoqueNo ratings yet

- DELTA OverviewDocument2 pagesDELTA OverviewlykiawindNo ratings yet

- Final Exam EssayDocument3 pagesFinal Exam Essayapi-520640729No ratings yet

- Instructional Planning for Triangle CongruenceDocument4 pagesInstructional Planning for Triangle CongruencePablo JimeneaNo ratings yet

- 020 - Cis - Dp734 - Cis Ms BecDocument2 pages020 - Cis - Dp734 - Cis Ms BecAnonymous waLfMudFYNo ratings yet

- Competency Based GuideDocument3 pagesCompetency Based GuideHafie JayNo ratings yet

- Bon Air Close Reading WorksheetDocument4 pagesBon Air Close Reading Worksheetapi-280058935No ratings yet

- DLL Mathematics 6 q4 w6Document7 pagesDLL Mathematics 6 q4 w6Enrique100% (1)

- Wilmington Head Start IncDocument10 pagesWilmington Head Start Incapi-355318161No ratings yet

- Santrock Section 5 (Chapter 9) Middle and Late ChildhoodDocument7 pagesSantrock Section 5 (Chapter 9) Middle and Late ChildhoodAssumpta Minette Burgos100% (2)

- Teacher ProfessionalismDocument6 pagesTeacher ProfessionalismBechir SaoudiNo ratings yet

- Final Portfolio EssayDocument7 pagesFinal Portfolio Essayapi-340129196No ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae-Sadia TasnimDocument3 pagesCurriculum Vitae-Sadia TasnimSadia Tasnim JotyNo ratings yet

- Verbal Abuse-Irony RaftDocument8 pagesVerbal Abuse-Irony Raftapi-282043501No ratings yet

- Teaching Methods and Instructional StrategiesDocument20 pagesTeaching Methods and Instructional Strategiescyril glenn jan auditorNo ratings yet

- Stewart K-Edid6512-Design-ProspectusDocument18 pagesStewart K-Edid6512-Design-Prospectusapi-432098444No ratings yet

- 27824Document47 pages27824Sandy Medyo GwapzNo ratings yet

- SDO Camarines Norte: Facilitating Dreams, Valuing AspirationsDocument6 pagesSDO Camarines Norte: Facilitating Dreams, Valuing AspirationsSalve SerranoNo ratings yet

- Home Guitar PraticeDocument3 pagesHome Guitar PraticekondamudisagarNo ratings yet

- Effective FCE Use of English: Word FormationDocument8 pagesEffective FCE Use of English: Word FormationYozamy TrianaNo ratings yet

- Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation From A Self-Determination Theory Perspective - Deci & Ryan (2020)Document31 pagesIntrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation From A Self-Determination Theory Perspective - Deci & Ryan (2020)Ngô DungNo ratings yet

- Comparative Education in Developing CountriesDocument16 pagesComparative Education in Developing CountriesPoppi HSNo ratings yet

- Correlational Research DesignDocument18 pagesCorrelational Research Designfebby100% (1)

- 7690-3638 High School Science Biology Student Resource Book 08-09Document240 pages7690-3638 High School Science Biology Student Resource Book 08-09Megaprofesor100% (3)

- Professional Reading Reflection EPPSP Phase I: SummaryDocument3 pagesProfessional Reading Reflection EPPSP Phase I: Summaryapi-508196283100% (1)

- Point of Entry: The Preschool-to-Prison PipelineDocument25 pagesPoint of Entry: The Preschool-to-Prison PipelineCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- 1389692008binder3Document35 pages1389692008binder3CoolerAdsNo ratings yet

- Instrument Flying Handbook PDFDocument371 pagesInstrument Flying Handbook PDFAshmi ShajiNo ratings yet

- Saint John's School Lesson Plan on Logarithm and Exponential EquationsDocument4 pagesSaint John's School Lesson Plan on Logarithm and Exponential EquationsRicky Antonius LNo ratings yet