Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Prosecutor Reprimanded for Failing to Remit SSS Contributions

Uploaded by

Elly Paul Andres Tomas0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

47 views2 pagesThe Supreme Court reprimanded respondent Prosecutor Diosdado Ibañez for professional misconduct. Ibañez failed to remit over 1,800 pesos given to him by Encarnacion Pascual for her Social Security System contributions. While Ibañez eventually paid the money after a complaint was filed against him over a year later, his failure to promptly remit the funds and the presumption that he misappropriated it for his own use constituted gross violations of legal ethics. The Court held that lawyers, including those in public service, have a duty of honesty, integrity and to promptly account for any money received on behalf of clients.

Original Description:

p vs i

Original Title

Penticostes vs Ibanez

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe Supreme Court reprimanded respondent Prosecutor Diosdado Ibañez for professional misconduct. Ibañez failed to remit over 1,800 pesos given to him by Encarnacion Pascual for her Social Security System contributions. While Ibañez eventually paid the money after a complaint was filed against him over a year later, his failure to promptly remit the funds and the presumption that he misappropriated it for his own use constituted gross violations of legal ethics. The Court held that lawyers, including those in public service, have a duty of honesty, integrity and to promptly account for any money received on behalf of clients.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

47 views2 pagesProsecutor Reprimanded for Failing to Remit SSS Contributions

Uploaded by

Elly Paul Andres TomasThe Supreme Court reprimanded respondent Prosecutor Diosdado Ibañez for professional misconduct. Ibañez failed to remit over 1,800 pesos given to him by Encarnacion Pascual for her Social Security System contributions. While Ibañez eventually paid the money after a complaint was filed against him over a year later, his failure to promptly remit the funds and the presumption that he misappropriated it for his own use constituted gross violations of legal ethics. The Court held that lawyers, including those in public service, have a duty of honesty, integrity and to promptly account for any money received on behalf of clients.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

EN BANC

[A.C. CBD No. 167. March 9, 1999]

ATTY. PRUDENCIO S. PENTICOSTES, complainant, vs. PROSECUTOR DIOSDADO S. IBAEZ, respondent.

R E S O L U T I O N

ROMERO, J.:

Sometime in 1989, Encarnacion Pascual, the sister-in-law of Atty. Prudencio S. Penticostes (herein

complainant) was sued for non-remittance of SSS payments. The complaint was docketed as I.S. 89-353 and

assigned to Prosecutor Diosdado S. Ibaez (herein respondent) for preliminary investigation. In the course

of the investigation, Encarnacion Pascual gave P1,804.00 to respondent as payment of her Social Security

System (SSS) contribution in arrears. Respondent, however, did not remit the amount to the system. The

fact of non-payment was certified to by the SSS on October 2, 1989.

On November 16, 1990 or over a year later, complainant filed with the Regional Trial Court of Tarlac a

complaint for professional misconduct against Ibaez due to the latters failure to remit the SSS

contributions of his sister-in-law. The complaint alleged that respondents misappropriation of Encarnacion

Pascuals SSS contributions amounted to a violation of his oath as a lawyer. Seven days later, or on

November 23, 1990, respondent paid P1,804.00 to the SSS on behalf of Encarnacion Pascual.

In the meantime, the case was referred to the Integrated Bar of the Philippines-Tarlac Chapter, the court

observing that it had no competence to receive evidence on the matter. Upon receipt of the case, the

Tarlac Chapter forwarded the same to IBPs Commission on Bar Discipline.

In his defense, respondent claimed that his act of accommodating Encarnacion Pascuals request to make

payment to the SSS did not amount to professional misconduct but was rather an act of Christian charity.

Furthermore, he claimed that the action was moot and academic, the amount of P1,804.00 having already

been paid by him to the SSS. Lastly, he disclaimed liability on the ground that the acts complained were not

done by him in his capacity as a practicing lawyer but on account of his office as a prosecutor.

On September 3, 1998, the Commission recommended that the respondent be reprimanded, with a

warning that the commission of the same or similar offense would be dealt with more severely in the

future. On November 5, 1998, the Board of Governors of the Integrated Bar of the Philippines adopted and

approved its Commissions recommendation.

This Court adopts the recommendation of the IBP and finds respondent guilty of professional misconduct.

While there is no doubt that payment of the contested amount had been effected to the SSS on November

23, 1990, it is clear however, that the same was made only after a complaint had been filed against

respondent. Furthermore, the duties of a provincial prosecutor do not include receiving money from

persons with official transactions with his office.

This Court has repeatedly admonished lawyers that a high sense of morality, honesty and fair dealing is

expected and required of a member of the bar. Rule 1.01 of the Code of Professional Responsibility

provides that *a+ lawyer shall not engage in unlawful, dishonest, immoral or deceitful conduct.

It is glaringly clear that respondents non-remittance for over one year of the funds coming from

Encarnacion Pascual constitutes conduct in gross violation of the above canon. The belated payment of the

same to the SSS does not excuse his misconduct. While Pascual may not strictly be considered a client of

respondent, the rules relating to a lawyers handling of funds of a client is applicable. In Daroy v. Legaspi,[1]

this court held that (t)he relation between an attorney and his client is highly fiduciary in nature...*thus+

lawyers are bound to promptly account for money or property received by them on behalf of their clients

and failure to do so constitutes professional misconduct. The failure of respondent to immediately remit

the amount to the SSS gives rise to the presumption that he has misappropriated it for his own use. This is

a gross violation of general morality as well as professional ethics; it impairs public confidence in the legal

profession and deserves punishment.[2]

Respondents claim that he may not be held liable because he committed such acts, not in his capacity as a

private lawyer, but as a prosecutor is unavailing. Canon 6 of the Code of Professional Responsibility

provides:

These canons shall apply to lawyers in government service in the discharge of their official tasks.

As stated by the IBP Committee that drafted the Code, a lawyer does not shed his professional obligations

upon assuming public office. In fact, his public office should make him more sensitive to his professional

obligations because a lawyers disreputable conduct is more likely to be magnified in the publics eye.*3+

Want of moral integrity is to be more severely condemned in a lawyer who holds a responsible public

office.[4]

ACCORDINGLY, this Court REPRIMANDS respondent with a STERN WARNING that a commission of the

similar offense will be dealt with more severely in the future.

LET copies of this decision be spread in his records and copies be furnished the Department of Justice and

the Office of the Bar Confidant.

SO ORDERED.

Davide, Jr., C.J., Bellosillo, Melo, Puno, Vitug, Kapunan, Mendoza, Panganiban, Quisumbing, Purisima, Pardo,

Buena, and Gonzaga-Reyes, JJ., concur.

PENTICOSTES VS. IBANEZ 304 SCRA 281

FACTS: The sister-in-law of Atty. Penticostes was sued for non- remittance of SSS payments. The

respondent, Pros. Ibanez was given by the sister-in-law of Penticostes P1,804 as payment of her SSS

contribution arrears but said respondent did not remit the amount to the system. Complainant filed with

the RTC a complaint for professional misconduct against Ibanez due to the latters failure to remit to the SSS

her contribution and for respondents misappropriation of the amount.

ISSUE: Whether or not respondents act amounted to violation of his oath as a lawyer.

HELD: Yes. Non-remittance by a public prosecutor for over one year of funds entrusted to him constitutes

conduct in gross violation of Rule 1.01 of the Code of Professional Responsibility which provides that a

lawyer shall not engage in unlawful, dishonest, immoral, or deceitful conduct. Lawyers are bound to

promptly account for money or property received by them on behalf of their clients and failure to do so

constitutes professional misconduct.

You might also like

- Pervertible Practices: Playing Anthropology in BDSM - Claire DalmynDocument5 pagesPervertible Practices: Playing Anthropology in BDSM - Claire Dalmynyorku_anthro_confNo ratings yet

- Week 4-LS1 Eng. LAS (Types of Verbals)Document14 pagesWeek 4-LS1 Eng. LAS (Types of Verbals)DONALYN VERGARA100% (1)

- BASIC LEGAL & JUDICIAL ETHICS - The ClientsDocument14 pagesBASIC LEGAL & JUDICIAL ETHICS - The ClientsAppleNo ratings yet

- Team Roles EssayDocument7 pagesTeam Roles EssayCecilie Elisabeth KristensenNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument44 pagesCase DigestJoanne BayyaNo ratings yet

- Kargil Untold StoriesDocument214 pagesKargil Untold StoriesSONALI KUMARINo ratings yet

- Pale CompilationDocument19 pagesPale CompilationRay Wilson Cajucom TolentinoNo ratings yet

- SC Reprimands Prosecutor for Failing to Remit SSS FundsDocument1 pageSC Reprimands Prosecutor for Failing to Remit SSS FundsmimslawNo ratings yet

- Lawyer Suspended for Failing to Transfer Land TitlesDocument7 pagesLawyer Suspended for Failing to Transfer Land TitlesVic DizonNo ratings yet

- Bar Exam Leakage and Lawyer MisconductDocument19 pagesBar Exam Leakage and Lawyer MisconductNestNo ratings yet

- Belleza v. Macasa, A.C. No. 7815, 23 July 2009Document2 pagesBelleza v. Macasa, A.C. No. 7815, 23 July 2009athenabeatrizNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics Case Digest on Negligence and Duty of LawyersDocument11 pagesLegal Ethics Case Digest on Negligence and Duty of LawyersFrancisco MarvinNo ratings yet

- Isidra Barrientos vs. Atty. Elerizza Libiran-Meteoro, A.C. No. 6408, August 31, 2004Document2 pagesIsidra Barrientos vs. Atty. Elerizza Libiran-Meteoro, A.C. No. 6408, August 31, 2004Lizzy LiezelNo ratings yet

- Case Digest On Lawyer's Duty To The CourtDocument21 pagesCase Digest On Lawyer's Duty To The CourtAlyanna AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Gonzales Vs Alcaraz 2006Document8 pagesGonzales Vs Alcaraz 2006thelawyer07No ratings yet

- PENTECOSTESDocument2 pagesPENTECOSTESViceni AlbaNo ratings yet

- Ramos Vs MandaganDocument2 pagesRamos Vs MandaganHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics CasesDocument9 pagesLegal Ethics CasesRojie Bong BlancoNo ratings yet

- Public Personnel AdministrationDocument2 pagesPublic Personnel AdministrationElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- CANON 11 Script ReportDocument10 pagesCANON 11 Script Reportkaren mariz manaNo ratings yet

- Cases in PALEDocument330 pagesCases in PALEdonyacarlotta100% (1)

- Ethics Canon 18 Up CompilationDocument21 pagesEthics Canon 18 Up CompilationRomielyn Macalinao100% (1)

- Lawyers Duties in Handling Clients Case CompleteDocument23 pagesLawyers Duties in Handling Clients Case CompleteAnne Lorraine DioknoNo ratings yet

- IN RE Edellion Legal EthicsDocument18 pagesIN RE Edellion Legal EthicsRaymond Vera Cruz VillarinNo ratings yet

- 4.penticostes v. Ibanez DigestDocument2 pages4.penticostes v. Ibanez DigestVanityHughNo ratings yet

- ATTY. PRUDENCIO S. PENTICOSTES, Complainant, vs. Prosecutor Diosdado S. Ibañez, RespondentDocument4 pagesATTY. PRUDENCIO S. PENTICOSTES, Complainant, vs. Prosecutor Diosdado S. Ibañez, RespondentAlyanna CabralNo ratings yet

- A.C. No. 167Document2 pagesA.C. No. 167Synnove BagalayNo ratings yet

- Atty. Prudencio S. Penticostes vs. Prosecutor Diosdado S. Ibañez FactsDocument2 pagesAtty. Prudencio S. Penticostes vs. Prosecutor Diosdado S. Ibañez FactsPammyNo ratings yet

- Salazar V QuiambaoDocument7 pagesSalazar V QuiambaojiminNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Suspends Lawyer for Failing to Transfer Property Title and Return Client FundsDocument13 pagesSupreme Court Suspends Lawyer for Failing to Transfer Property Title and Return Client Fundsclaire beltranNo ratings yet

- Salazar v. QuiambaoDocument4 pagesSalazar v. QuiambaoANNA MARIE MENDOZANo ratings yet

- Rollon RevisitedDocument8 pagesRollon RevisitedmndzNo ratings yet

- Tejada vs. PalanaDocument4 pagesTejada vs. PalanaBowthen BoocNo ratings yet

- 1 A.C. No. 6424Document5 pages1 A.C. No. 6424Jessel MaglinteNo ratings yet

- Complainant Vs Vs Respondent: Third DivisionDocument3 pagesComplainant Vs Vs Respondent: Third DivisionVenice Jamaila DagcutanNo ratings yet

- Reflection Paper On PALE-finalDocument13 pagesReflection Paper On PALE-finalMA LOVELLA OSUMO100% (2)

- Spouses Lopez V Atty. LimotDocument2 pagesSpouses Lopez V Atty. LimotMariz EnocNo ratings yet

- Canon 2Document6 pagesCanon 2Jovz BumohyaNo ratings yet

- #56 SOCORRO T. CO, Complainant, vs. ATTY. GODOFREDO N. BERNARDINO, Respondent. FactsDocument12 pages#56 SOCORRO T. CO, Complainant, vs. ATTY. GODOFREDO N. BERNARDINO, Respondent. FactsBrian Zakhary SantiagoNo ratings yet

- ADM. CASE No. 5364 August 20, 2008Document3 pagesADM. CASE No. 5364 August 20, 2008isutitialex19.1No ratings yet

- PALE #1 CDsDocument9 pagesPALE #1 CDsKess MontallanaNo ratings yet

- 11663Document3 pages11663Edwin VillaNo ratings yet

- 05-Sps. Tejada v. Atty. Palaña A.C. No. 7434 August 23, 2007Document4 pages05-Sps. Tejada v. Atty. Palaña A.C. No. 7434 August 23, 2007Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- Lawyer Suspended for Neglecting Client CaseDocument15 pagesLawyer Suspended for Neglecting Client CaseMargarette Pinkihan SarmientoNo ratings yet

- A.C. No. 5082Document4 pagesA.C. No. 5082Analou Agustin VillezaNo ratings yet

- Remigio PDocument3 pagesRemigio PMona LizaNo ratings yet

- Petitioners Vs Vs Respondent: Second DivisionDocument5 pagesPetitioners Vs Vs Respondent: Second DivisionJoko DinsayNo ratings yet

- Salazar Vs Atty QuiambaoDocument7 pagesSalazar Vs Atty QuiambaoMyza AgyaoNo ratings yet

- Atty fails to file adoption caseDocument5 pagesAtty fails to file adoption caseJezra DelfinNo ratings yet

- Legal EthicsDocument4 pagesLegal EthicsBannylyn Mae Silaroy GamitNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics Case DigestDocument14 pagesLegal Ethics Case DigestBarbara MaeNo ratings yet

- Lopez Vs LimosDocument13 pagesLopez Vs LimosJustin YañezNo ratings yet

- Lawyer Suspended for Neglecting Legal MatterDocument5 pagesLawyer Suspended for Neglecting Legal MattersobranggandakoNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Suspends Lawyer for Falsifying ChecksDocument2 pagesSupreme Court Suspends Lawyer for Falsifying Checksiaton77No ratings yet

- LAW I.Q.: Case BriefDocument4 pagesLAW I.Q.: Case BriefZsazsaNo ratings yet

- PaleDocument10 pagesPaleMhayBinuyaJuanzonNo ratings yet

- 11 Go vs. Buri, AC No. 12296, December 4, 2018Document5 pages11 Go vs. Buri, AC No. 12296, December 4, 2018DeniseNo ratings yet

- Espiritu Vs Cabredo IVDocument5 pagesEspiritu Vs Cabredo IVKristine May CisterNo ratings yet

- Grande V de Silva (2003)Document4 pagesGrande V de Silva (2003)ChengNo ratings yet

- PALE - Money Matters - Comingling and Delivery of FundsDocument30 pagesPALE - Money Matters - Comingling and Delivery of FundsRonna Faith MonzonNo ratings yet

- Cariaga vs. People: Supreme Court Relaxes Rules to Forward Appeal to Proper CourtDocument6 pagesCariaga vs. People: Supreme Court Relaxes Rules to Forward Appeal to Proper CourtJhoanne PoncianoNo ratings yet

- Canon 12 - A Lawyer Shall Exert Every Effort and Consider It His Duty To Assist in The Speedy and Efficient Administration of JusticeDocument10 pagesCanon 12 - A Lawyer Shall Exert Every Effort and Consider It His Duty To Assist in The Speedy and Efficient Administration of JusticeMhayBinuyaJuanzonNo ratings yet

- Lorenzo Vs CaDocument3 pagesLorenzo Vs CaulticonNo ratings yet

- Admission To Practice 11-20Document15 pagesAdmission To Practice 11-20Von paulo AnonuevoNo ratings yet

- Soil PHDocument19 pagesSoil PHElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

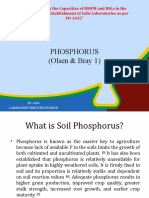

- Phosphorus (Olsen & Bray 1)Document34 pagesPhosphorus (Olsen & Bray 1)Elly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Organic MatterDocument11 pagesOrganic MatterElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Total NitrogenDocument14 pagesTotal NitrogenElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Payment of Claims - AuditChecklist - Template - DA12Document15 pagesPayment of Claims - AuditChecklist - Template - DA12Elly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Workshop 1 Interested PartiesDocument1 pageWorkshop 1 Interested PartiesElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Team Elly AuditPlan - IQA - DA12 - TemplateDocument4 pagesTeam Elly AuditPlan - IQA - DA12 - TemplateElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Standard IA ChecklistDocument23 pagesStandard IA ChecklistElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Workshop 4 ILD ProcessesDocument6 pagesWorkshop 4 ILD ProcessesElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Writing An Article Critique - UAGC Writing CenterDocument4 pagesWriting An Article Critique - UAGC Writing CenterElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- ISO 9001:2015 Self-Assessment Checklist: National Highway Authority (NHA)Document2 pagesISO 9001:2015 Self-Assessment Checklist: National Highway Authority (NHA)Elly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Team Elly Exercise 1Document1 pageTeam Elly Exercise 1Elly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Workshop 3 Sample Receiving Risk AssessmentdocxDocument2 pagesWorkshop 3 Sample Receiving Risk AssessmentdocxElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- LimingDocument11 pagesLimingElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Team Elly Exercise 1Document1 pageTeam Elly Exercise 1Elly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Hosting ScriptDocument4 pagesHosting ScriptElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- HeheheDocument2 pagesHeheheElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- SDS 204 - Environmental Laws NotesDocument4 pagesSDS 204 - Environmental Laws NotesElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Accreditation of CPD Provider and Program PRC 12Document35 pagesAccreditation of CPD Provider and Program PRC 12Elly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Updates, Trends and Outlook On The Fertilizer IndustryDocument24 pagesUpdates, Trends and Outlook On The Fertilizer IndustryElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Legume Green ManuringDocument2 pagesLegume Green ManuringElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Successful Registration PageDocument1 pageSuccessful Registration PageSamuel SchwartzNo ratings yet

- English BSWM BFS PresentationDocument19 pagesEnglish BSWM BFS PresentationElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Analytical ServicesDocument4 pagesAnalytical ServicesElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Records Management in ReviewDocument17 pagesRecords Management in ReviewElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Eqp.001 02 Thermometer CalibDocument4 pagesEqp.001 02 Thermometer CalibElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Successful Registration PageDocument1 pageSuccessful Registration PageSamuel SchwartzNo ratings yet

- Word Art FormatDocument1 pageWord Art FormatElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- InventDocument2 pagesInventElly Paul Andres TomasNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Manajemen IndonesiaDocument20 pagesJurnal Manajemen IndonesiaThoriq MNo ratings yet

- Daft Presentation 6 EnvironmentDocument18 pagesDaft Presentation 6 EnvironmentJuan Manuel OvalleNo ratings yet

- Group Assignment Topics - BEO6500 Economics For ManagementDocument3 pagesGroup Assignment Topics - BEO6500 Economics For ManagementnoylupNo ratings yet

- Decision Support System for Online ScholarshipDocument3 pagesDecision Support System for Online ScholarshipRONALD RIVERANo ratings yet

- SyllabusDocument8 pagesSyllabusrickyangnwNo ratings yet

- 0807 Ifric 16Document3 pages0807 Ifric 16SohelNo ratings yet

- Virtuoso 2011Document424 pagesVirtuoso 2011rraaccNo ratings yet

- 2-Library - IJLSR - Information - SumanDocument10 pages2-Library - IJLSR - Information - SumanTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Puberty and The Tanner StagesDocument2 pagesPuberty and The Tanner StagesPramedicaPerdanaPutraNo ratings yet

- Solar Presentation – University of Texas Chem. EngineeringDocument67 pagesSolar Presentation – University of Texas Chem. EngineeringMardi RahardjoNo ratings yet

- Term2 WS7 Revision2 PDFDocument5 pagesTerm2 WS7 Revision2 PDFrekhaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document11 pagesChapter 1Albert BugasNo ratings yet

- Ettercap PDFDocument13 pagesEttercap PDFwyxchari3No ratings yet

- Kristine Karen DavilaDocument3 pagesKristine Karen DavilaMark anthony GironellaNo ratings yet

- 01.09 Create EA For Binary OptionsDocument11 pages01.09 Create EA For Binary OptionsEnrique BlancoNo ratings yet

- Executive Support SystemDocument12 pagesExecutive Support SystemSachin Kumar Bassi100% (2)

- Pembaruan Hukum Melalui Lembaga PraperadilanDocument20 pagesPembaruan Hukum Melalui Lembaga PraperadilanBebekliarNo ratings yet

- Chemistry Sample Paper 2021-22Document16 pagesChemistry Sample Paper 2021-22sarthak MongaNo ratings yet

- Summer 2011 Redwood Coast Land Conservancy NewsletterDocument6 pagesSummer 2011 Redwood Coast Land Conservancy NewsletterRedwood Coast Land ConservancyNo ratings yet

- Zeng 2020Document11 pagesZeng 2020Inácio RibeiroNo ratings yet

- UAE Cooling Tower Blow DownDocument3 pagesUAE Cooling Tower Blow DownRamkiNo ratings yet

- Hand Infection Guide: Felons to Flexor TenosynovitisDocument68 pagesHand Infection Guide: Felons to Flexor TenosynovitisSuren VishvanathNo ratings yet

- SS2 8113 0200 16Document16 pagesSS2 8113 0200 16hidayatNo ratings yet

- Derivatives 17 Session1to4Document209 pagesDerivatives 17 Session1to4anon_297958811No ratings yet

- MCI FMGE Previous Year Solved Question Paper 2003Document0 pagesMCI FMGE Previous Year Solved Question Paper 2003Sharat Chandra100% (1)

- De Minimis and Fringe BenefitsDocument14 pagesDe Minimis and Fringe BenefitsCza PeñaNo ratings yet