Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lazarte SUPREME COURT CASE

Uploaded by

Raymart Zervoulakos Isais0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

533 views14 pagesSCRA

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentSCRA

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

533 views14 pagesLazarte SUPREME COURT CASE

Uploaded by

Raymart Zervoulakos IsaisSCRA

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 14

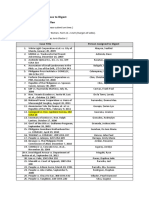

Consolidated case digests for Criminal Procedure

Maria Victoria Z. Matillano, Set 1 Final Half

People vs. Odilao

Facts: Herein respondent David S. Odilao, Jr.

together with Enrique Samonte and Mario Yares,

was charged with Estafa in an Information[2] filed

by the Asst. City Prosecutor Feliciano with the

RTC of Cebu City.

the said accused, conniving, confederating and

mutually helping with one another, having

received in trust from Trans Eagle Corporation a

luxury car known as Jeep Cherokee Sport 4wd

valued at P1,199,520.00 with the agreement that

they would sign the document of sale if they are

interested to buy the same and with the

obligation to return the said car to Trans Eagle

Corporation if they are not interested, the said

accused, once in possession of the said luxury car,

far from complying with their obligation, with

deliberate intent, with intent to gain, with

unfaithfulness and grave abuse of confidence, did

then and there misappropriate, misapply and

convert into their own personal use and benefit

the same or the amount of P1,199,520.00 which

is the equivalent value thereof, and inspite of

repeated demands made upon them to let them

comply with their obligation to return the luxury

car, they have failed and refused and instead

denied to have received the luxury car known as

Jeep Cherokee Sport 4WD and up to the

present time still fail and refuse to do so, to the

damage and prejudice of Trans Eagle Corporation

in the amount aforestated.

Issue: W/N the court of appeals committed

reversible error in granting the injunction sought

by the respondent which enjoined the trial court

from implementing the warrant of arrest and

from further conducting proceedings in the case

until the petition for review of the reinvestigation

report of the city prosecutor is resolved by the

department of justice?

Held:

the Court enunciated the following ruling in

Crespo vs. Mogul,[23] to wit:

The preliminary investigation conducted by the

fiscal for the purpose of determining whether a

prima facie case exists warranting the

prosecution of the accused is terminated upon

the filing of the information in the proper court.

In turn, as above stated, the filing of said

information sets in motion the criminal action

against the accused in Court. Should the fiscal

find it proper to conduct a reinvestigation of the

case, at such stage, the permission of the Court

must be secured. After such reinvestigation the

finding and recommendations of the fiscal should

be submitted to the Court for appropriate action.

While it is true that the fiscal has the quasi judicial

discretion to determine whether or not a criminal

case should be filed in court or not, once the case

had already been brought to Court whatever

disposition the fiscal may feel should be proper in

the case thereafter should be addressed for the

consideration of the Court. The only qualification

is that the action of the Court must not impair the

substantial rights of the accused or the right of

the People to due process of law.

Whether the accused had been arraigned or not

and whether it was due to a reinvestigation by

the fiscal or a review by the Secretary of Justice

whereby a motion to dismiss was submitted to

the Court, the Court in the exercise of its

discretion may grant the motion or deny it and

require that the trial on the merits proceed for

the proper determination of the case.

However, one may ask, if the trial court refuses

to grant the motion to dismiss filed by the fiscal

upon the directive of the Secretary of Justice will

there not be a vacuum in the prosecution? . . .

The answer is simple. The role of the fiscal or

prosecutor as We all know is to see that justice is

done and not necessarily to secure the conviction

of the person accused before the Courts. Thus, in

spite of his opinion to the contrary, it is the duty

of the fiscal to proceed with the presentation of

evidence of the prosecution to the Court to

enable the Court to arrive at its own independent

Yes. The rule in this jurisdiction is that once a

complaint or information is filed in Court any

disposition of the case as its dismissal or the

conviction or acquittal of the accused rests in the

sound discretion of the Court. Although the fiscal

retains the direction and control of the

prosecution of criminal cases even while the case

is already in Court he cannot impose his opinion

on the trial court. The Court is the best and sole

judge on what to do with the case before it. The

determination of the case is within its exclusive

jurisdiction and competence. A motion to dismiss

the case filed by the fiscal should be addressed

to the Court who has the option to grant or deny

the same. It does not matter if this is done

before or after the arraignment of the accused

or that the motion was filed after a

reinvestigation or upon instructions of the

Secretary of Justice who reviewed the records of

the investigation.

Thus, in Perez vs. Hagonoy Rural Bank, Inc.,[24]

the Court held that the trial court judges

reliance on the prosecutors averment that the

Consolidated case digests for Criminal Procedure

Maria Victoria Z. Matillano, Set 1 Final Half

Secretary of Justice had recommended the

dismissal of the case against the petitioner was,

to say the least, an abdication of the trial courts

duty and jurisdiction to determine a prima facie

case, in blatant violation of this Courts

pronouncement in Crespo vs. Mogul .

IT BEARS STRESSING THAT THE COURT IS

HOWEVER NOT BOUND TO ADOPT THE

RESOLUTION OF THE SECRETARY OF JUSTICE

SINCE THE COURT IS MANDATED TO

INDEPENDENTLY EVALUATE OR ASSESS THE

MERITS OF THE CASE, AND MAY EITHER AGREE

OR DISAGREE WITH THE RECOMMENDATION OF

THE SECRETARY OF JUSTICE. RELIANCE ALONE ON

THE RESOLUTION OF THE SECRETARY OF JUSTICE

WOULD BE AN ABDICATION OF THE TRIAL

COURTS DUTY AND JURISDICTION TO

DETERMINE PRIMA FACIE CASE.

Verily, the proceedings in the criminal case

pending in the trial court had been held in

abeyance long enough. Under Section 11, Rule

116 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure,

the suspension of arraignment of an accused in

cases where a petition for review of the

resolution of the prosecutor is pending at either

the Department of Justice or the Office of the

President shall not exceed sixty days counted

from the filing of the petition with the reviewing

office. Although in this case, at the time that the

trial court deferred the arraignment in its Order

dated October 30, 2000, the Revised Rules of

Criminal Procedure had not yet taken effect and

there was as yet no prescribed period of time for

the suspension of arraignment, we believe that

the period of one and a half years from October

30, 2000 to June 13, 2002, when the trial court

ordered the implementation of the warrant of

arrest, was more than ample time to give private

complainant the opportunity to obtain a

resolution of her petition for review from the

DOJ. Indeed, with more than three years having

elapsed, it is now high time for the continuation

of the trial on the merits in the criminal case

below as the sixty-day period counted from the

filing of the petition for review with the DOJ,

provided for in Section 11, Rule 116 of the

Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure now

applicable to the case at bar, had long lapsed.

People vs. Oden

Facts: The Court is confronted with yet another

case where a home ceases being an abode of

safety and protection, this time to a motherless

daughter who has accused her own father, herein

appellant, of having repeatedly had carnal

knowledge of her "by means of force and

intimidation." Appellant Mario Oden was charged

with twelve (12) counts of "rape,".

"Due to fear, Anna Liza did not report to anyone

all the twelve (12) incidents of sexual

molestation.

"However, unknown to Anna Liza, her Ate Mercy

(wife of the complainants brother Arnold Oden)

witnessed the rape that took place on 08 January

2001. Ate Mercy saw through a small hole on the

wall inside the house - separating her bedroom

from that of Anna Lizas what accused had done

to her (Anna Liza). And it was not only Ate Mercy

who witnessed the rape. Arnold Oden (brother of

Anna Liza) also saw what the accused had done to

Anna Liza. Arnold was mad at accused; however

he was not able to do anything because he,

together with the rest of the siblings, were afraid

of their father (accused) - the reason being that

everytime accused would get angry, he would

beat all of them.

"Nonetheless, Ate Mercy reported to a neighbor,

Nanay Ludy, Anna Lizas harrowing experience on

08 January 2001. In turn, Nanay Ludy talked to

Anna Liza and directed her to report the incident

to the barangay. Anna Liza heeded Nanay Ludys

directive. She proceeded to the barangay -

together with her Ate Mercy and Ate Marilou

(wives of Anna Lizas older brothers) - and

reported her fathers outrageous wrongdoings.

On 28 January 2001, based on Anna Lizas sworn

statement, the barangay officials, together with

the police, arrested accused-appellant."2

After the prosecution had rested its case with the

testimony of its lone witness (the private

complainant), Atty. Harley Padolina (PAO)

manifested that the defense would not present

any evidence.

Issue: W/N the accused plea has been

improvidently made? YES

Held: In the review of his various cases by this

Court, appellant asserts that his plea of guilty has

been improvidently made on the mistaken belief

that he would be given a lighter penalty with his

plea of guilt.4 On this particular score, the

Solicitor General agrees.

THERE IS MERIT IN THE OBSERVATION.

Section 3, Rule 116, of the 2000 Rules of Criminal

Procedure is explicit on the procedure to be taken

when an accused pleads guilty to a capital

offense, viz:

"SEC. 3. Plea of guilty to capital offense; reception

of evidence. - When the accused pleads guilty to a

capital offense, the court shall conduct a

searching inquiry into the voluntariness and full

Consolidated case digests for Criminal Procedure

Maria Victoria Z. Matillano, Set 1 Final Half

comprehension of the consequences of his plea

and shall require the prosecution to prove his

guilt and the precise degree of culpability. The

accused may present evidence in his behalf."

The trial court is mandated (1) to conduct a

searching inquiry into the voluntariness and full

comprehension of the consequences of the plea

of guilt, (2) to require the prosecution to still

prove the guilt of the accused and the precise

degree of his culpability, and (3) to inquire

whether or not the accused wishes to present

evidence on his behalf and allow him to do so if

he desires. The records must show the events

that have actually taken place during the inquiry,

the words spoken and the warnings given, with

special attention to the age of the accused, his

educational attainment and socio-economic

status, the manner of his arrest and detention,

the attendance of counsel in his behalf during the

custodial and preliminary investigations, and the

opportunity of his defense counsel to confer with

him. All these matters should be able to provide

trustworthy indices of his competence to give a

free and informed plea of guilt. The trial court

must describe the essential elements of the

crimes the accused is charged with and their

respective penalties and civil liabilities. It should

also direct a series of questions to defense

counsel to determine whether or not he has

conferred with the accused and has completely

explained to him the legal implications of a plea

of guilt.5

The process is mandatory and absent any

showing that it has been duly observed, a

searching inquiry cannot be said to have been

aptly undertaken.6 The trial court must be extra

solicitous to see to it that the accused fully

understands the meaning and importance of his

plea. In capital offenses7 particularly, life being at

stake, one cannot just lean on the presumption

that the accused has understood his plea.8

While the records of the case are indeed bereft of

any indication that the rule has sufficiently been

complied with, the evidence for the prosecution

outside of the plea of guilt, nevertheless, would

adequately establish the guilt of appellant beyond

reasonable doubt.9 THE MANNER BY WHICH THE

PLEA OF GUILT IS MADE, WHETHER

IMPROVIDENTLY OR NOT, LOSES MUCH OF GREAT

SIGNIFICANCE WHERE THE CONVICTION CAN BE

BASED ON INDEPENDENT EVIDENCE PROVING

THE COMMISSION BY THE PERSON ACCUSED OF

THE OFFENSE CHARGED.10

THE PROSECUTION PRESENTED AT THE WITNESS

STAND ANNA LIZA. SHE RECOUNTED

STRAIGHTFORWARDLY AND IN SUFFICIENT

DETAIL THE TWELVE HARROWING AND

HUMILIATING INCIDENTS OF RAPE SHE HAD

SUFFERED IN THE HANDS OF HER OWN FATHER.

Soriano vs. People, BSP and PDIC

Facts: A bank officer violates the DOSRI 2 law

when he acquires bank funds for his personal

benefit, even if such acquisition was facilitated by

a fraudulent loan application. Directors, officers,

stockholders, and their related interests cannot

be allowed to interpose the fraudulent nature of

the loan as a defense to escape culpability for

their circumvention of Section 83 of Republic Act

(RA) No. 337. HILARIO P. SORIANO and

ROSALINDA ILAGAN, as principals by direct

participation, with unfaithfulness or abuse of

confidence and taking advantage of their position

as President of the Rural Bank of San Miguel

(Bulacan), Inc. and Branch Manager of the Rural

Bank of San Miguel-San Miguel Branch [sic], a

duly organized banking institution under

Philippine Laws, conspiring confederating and

mutually helping one another, did then and there,

willfully and feloniously by making it appear that

one Enrico Carlos filled up the

application/information sheet and filed the

aforementioned loan documents when in truth

and in fact Enrico Carlos did not participate in the

execution of said loan documents and that by

virtue of said falsification and with deceit and

intent to cause damage, the accused succeeded in

securing a loan in the amount of eight million

pesos (PhP8,000,000.00) from the Rural Bank of

San Miguel-San Ildefonso branch in the name of

Enrico Carlos which amount of PhP8 million

representing the loan proceeds the accused

thereafter converted the same amount to their

own personal gain and benefit, to the damage

and prejudice of the Rural Bank of San Miguel-San

Ildefonso branch, its creditors, the Bangko Sentral

ng Pilipinas, and the Philippine Deposit Insurance

Corporation.

The other Information 17 dated November 10,

2000 and docketed as Criminal Case No. 238-M-

2001, was for violation of Section 83 of RA 337, as

amended by PD 1795. The said provision refers to

the prohibition against the so-called DOSRI loans.

NOTE: 2 INFORMATION WAS FILED ESTAFA and

VIOLATION OF DOSRI LAWS

RULING OF THE COURT OF APPEALS

The CA denied the petition on both issues

presented by petitioner. On the first issue, the CA

determined that the BSP letter, which petitioner

characterized to be a fatally infirm complaint, was

not actually a complaint, but a transmittal or

Consolidated case digests for Criminal Procedure

Maria Victoria Z. Matillano, Set 1 Final Half

cover letter only. This transmittal letter merely

contained a summary of the affidavits which were

attached to it. It did not contain any averment of

personal knowledge of the events and

transactions that constitute the elements of the

offenses charged. Being a mere transmittal letter,

it need not comply with the requirements of

Section 3 (a) of Rule 112 of the Rules of Court. 30

The CA further determined that the five affidavits

attached to the transmittal letter should be

considered as the complaint-affidavits that

charged petitioner with violation of Section 83 of

RA 337 and for Estafa thru Falsification of

Commercial Documents. These complaint-

affidavits complied with the mandatory

requirements set out in the Rules of Court they

were subscribed and sworn to before a notary

public and subsequently certified by State

Prosecutor Fonacier, who personally examined

the affiants and was convinced that the affiants

fully understood their sworn statements. 31

AEScHa

ANENT THE SECOND GROUND, THE CA FOUND

NO MERIT IN PETITIONER'S ARGUMENT THAT THE

VIOLATION OF THE DOSRI LAW AND THE

COMMISSION OF ESTAFA THRU FALSIFICATION OF

COMMERCIAL DOCUMENTS ARE INHERENTLY

INCONSISTENT WITH EACH OTHER. It explained

that the test in considering a motion to quash on

the ground that the facts charged do not

constitute an offense, is whether the facts

alleged, when hypothetically admitted, constitute

the elements of the offense charged. The

appellate court held that this test was sufficiently

met because the allegations in the assailed

informations, when hypothetically admitted,

clearly constitute the elements of Estafa thru

Falsification of Commercial Documents and

Violation of DOSRI law. 32

On June 8, 2001, petitioner moved to quash 21

these informations on two grounds: that the

court had no jurisdiction over the offense

charged, and that the facts charged do not

constitute an offense.

Petitioners Motion for Reconsideration was

denied for lack of merit.

Issues:

1. Is a petition for certiorari under Rule 65

the proper remedy against an Order

denying a Motion to Quash?

2. Is a Rule 65 petition for certiorari the

proper remedy against an Order denying

a Motion to Quash?

1

st

Issued Held:

The second issue was raised by petitioner in the

context of his Motion to Quash Information on

the ground that the facts charged do not

constitute an offense. 43 It is settled that in

considering a motion to quash on such ground,

the test is "whether the facts alleged, if

hypothetically admitted, would establish the

essential elements of the offense charged as

defined by law. The trial court may not consider a

situation contrary to that set forth in the criminal

complaint or information. Facts that constitute

the defense of the petitioner[s] against the

charge under the information must be proved by

[him] during trial. Such facts or circumstances do

not constitute proper grounds for a motion to

quash the information on the ground that the

material averments do not constitute the

offense". 44 SaITHC

We have examined the two informations against

petitioner and we find that they contain

allegations which, if hypothetically admitted,

would establish the essential elements of the

crime of DOSRI violation and estafa thru

falsification of commercial documents.

In Criminal Case No. 238-M-2001 for violation of

DOSRI rules, the information alleged that

petitioner Soriano was the president of RBSM;

that he was able to indirectly obtain a loan from

RBSM by putting the loan in the name of

depositor Enrico Carlos; and that he did this

without complying with the requisite board

approval, reportorial, and ceiling requirements.

In Criminal Case No. 237-M-2001 for estafa thru

falsification of commercial documents, the

information alleged that petitioner, by taking

advantage of his position as president of RBSM,

falsified various loan documents to make it

appear that an Enrico Carlos secured a loan of P8

million from RBSM; that petitioner succeeded in

obtaining the loan proceeds; that he later

converted the loan proceeds to his own personal

gain and benefit; and that his action caused

damage and prejudice to RBSM, its creditors, the

BSP, and the PDIC. TEHIaD

Significantly, this is not the first occasion that we

adjudge the sufficiency of similarly worded

informations. In Soriano v. People, 45 involving

the same petitioner in this case (but different

transactions), we also reviewed the sufficiency of

informations for DOSRI violation and estafa thru

falsification of commercial documents, which

were almost identical, mutatis mutandis, with the

subject informations herein. We held in Soriano v.

People

that there is no basis for the quashal of the

informations as "they contain material allegations

Consolidated case digests for Criminal Procedure

Maria Victoria Z. Matillano, Set 1 Final Half

charging Soriano with violation of DOSRI rules and

estafa thru falsification of commercial

documents".

Petitioner raises the theory that he could not

possibly be held liable for estafa in concurrence

with the charge for DOSRI violation. According to

him, the DOSRI charge presupposes that he

acquired a loan, which would make the loan

proceeds his own money and which he could

neither possibly misappropriate nor convert to

the prejudice of another, as required by the

statutory definition of estafa. 46 On the other

hand, if petitioner did not acquire any loan, there

can be no DOSRI violation to speak of. Thus,

petitioner posits that the two offenses cannot co-

exist. This theory does not persuade us.

Petitioner's theory is based on the false premises

that the loan was extended to him by the bank in

his own name, and that he became the owner of

the loan proceeds. Both premises are wrong.

ACTISE

The bank money (amounting to P8 million) which

came to the possession of petitioner was money

held in trust or administration by him for the

bank, in his fiduciary capacity as the President of

said bank. 47 It is not accurate to say that

petitioner became the owner of the P8 million

because it was the proceeds of a loan. That would

have been correct if the bank knowingly extended

the loan to petitioner himself. But that is not the

case here. According to the information for

estafa, the loan was supposed to be for another

person, a certain "Enrico Carlos"; petitioner,

through falsification, made it appear that said

"Enrico Carlos" applied for the loan when in fact

he ("Enrico Carlos") did not. Through such

fraudulent device, petitioner obtained the loan

proceeds and converted the same. Under these

circumstances, it cannot be said that petitioner

became the legal owner of the P8 million. Thus,

petitioner remained the bank's fiduciary with

respect to that money, which makes it capable of

misappropriation or conversion in his hands.

The next question is whether there can also be, at

the same time, a charge for DOSRI violation in

such a situation wherein the accused bank officer

did not secure a loan in his own name, but was

alleged to have used the name of another person

in order to indirectly secure a loan from the bank.

We answer this in the affirmative. In sum, the

informations filed against petitioner do not

negate each other.

2

nd

Issue Held:

In fine, the Court has consistently held that a

special civil action for certiorari is not the proper

remedy to assail the denial of a motion to quash

an information. The proper procedure in such a

case is for the accused to enter a plea, go to trial

without prejudice on his part to present the

special defenses he had invoked in his motion to

quash and if after trial on the merits, an adverse

decision is rendered, to appeal therefrom in the

manner authorized by law. Thus, petitioners

should not have forthwith filed a special civil

action for certiorari with the CA and instead, they

should have gone to trial and reiterated the

special defenses contained in their motion to

quash. There are no special or exceptional

circumstances in the present case that would

justify immediate resort to a filing of a petition for

certiorari. Clearly, the CA did not commit any

reversible error, much less, grave abuse of

discretion in dismissing the petition.

People vs. Elarcosa and Orias

Facts: Jorge, Segundina, Jose and Rosemarie, all

surnamed dela Cruz, heard some persons calling

out to them from outside their house, which is

located Negros Occidental. Since the voices of

these persons were not familiar to them, they did

not open their door immediately, and instead,

they waited for a few minutes in order to observe

and recognize these persons first. It was only

when one of them identified himself as Mitsuel L.

Elarcosa (Elarcosa), an acquaintance of the family,

that Segundina lighted the lamps, while Jose

opened the door. 1 Elarcosa and his companion,

accused-appellant Orias, then entered the house

and requested that supper be prepared for them

as they were roving. Both Elarcosa and accused-

appellant Orias were Citizen Armed Forces

Geographical Unit (CAFGU) members. 2

Segundina and Rosemarie immediately went to

the kitchen to prepare food, while Jose and Jorge

stayed in the living room with Elarcosa and

accused-appellant Orias. 3

Since the rice was not cooked yet, Rosemarie first

served a plate of suman to Elarcosa and accused-

appellant Orias, who were then engaged in a

conversation with her father, Jorge, and her

brother, Jose. She heard accused-appellant Orias

asked her brother why the latter did not attend

the dance at Sitio Nalibog. Her brother replied

that he was tired. Suddenly thereafter, Elarcosa

and accused-appellant Orias stood up and fired

their guns at Jose and Jorge.

Segundina, who was busy preparing supper in the

kitchen, ran towards the living room and

embraced her son, Jose, who was already lying on

the floor. Elarcosa and accused-appellant Orias

then immediately searched the wooden chest

containing clothes, money in the amount of forty

Consolidated case digests for Criminal Procedure

Maria Victoria Z. Matillano, Set 1 Final Half

thousand pesos (PhP40,000) intended for the

forthcoming wedding of Jose in October, and a

registration certificate of large cattle. During this

time, Rosemarie escaped through the kitchen and

hid in the shrubs, which was about six (6)

extended arms length from their house. She

heard her mother crying loudly, and after a series

of gunshots, silence ensued. 5

Shortly thereafter, Rosemarie proceeded to the

house of her cousin, Gualberto Mechabe, who

advised her to stay in the house until the morning

since it was already dark and he had no other

companion who could help them. The following

morning, Rosemarie returned to their house

where she found the dead bodies of her parents

and her brother. 6 The money in the amount of

PhP40,000, as well as the certificate of

registration of large cattle, were also gone. 7

Eventually, Elarcosa and accused-appellant Orias,

as well as a certain Antonio David, Jr., were

charged with robbery with multiple homicide.

Issues:

1. W/N alibi of accused-appellant Orias

should be given wheight. NO

2. W/N there is duplicity of offense?

(ground for a MTQ) YES

Held:

1

st

Issue:

Although the alibi of accused-appellant Orias

appears to have been corroborated by a CAFGU

member by the name of Robert Arellano and by a

vendor present during the dance, said defense is

unworthy of belief not only because of its

inherent weakness and the fact that accused-

appellant Orias was positively identified by

Rosemarie, but also because it has been held that

alibi becomes more unworthy of merit where it is

established mainly by the accused himself, his

relatives, friends, and comrades-in-arms, 37 and

not by credible persons.

2

nd

Issue:

In the instant case, conspiracy is manifested by

the fact that the acts of accused-appellant Orias

and Elarcosa were coordinated. They were

synchronized in their approach to shoot Jose and

Jorge, and they were motivated by a single

criminal impulse, that is, to kill the victims. Verily,

conspiracy is implied when the accused persons

had a common purpose and were united in its

execution. Spontaneous agreement or active

cooperation by all perpetrators at the moment of

the commission of the crime is sufficient to create

joint criminal responsibility. 49

ACCUSED-APPELLANT ORIAS SHOULD BE

CONVICTED OF THREE (3) COUNTS OF MURDER

AND NOT OF THE COMPLEX CRIME OF MURDER

We, however, disagree with the findings of the CA

that accused-appellant Orias committed the

complex crime of multiple murder. Article 48 of

the Revised Penal Code, which defines the

concept of complex crime, states:

ART. 48. Penalty for complex crimes. When a

single act constitutes two or more grave or less

grave felonies or when an offense is a necessary

means for committing the other, the penalty for

the most serious crime shall be imposed, the

same to be applied in its maximum period. (As

amended by Act No. 4000.)

In a complex crime, although two or more crimes

are actually committed, they constitute only one

crime in the eyes of the law, as well as in the

conscience of the offender. Hence, there is only

one penalty imposed for the commission of a

complex crime. Complex crime has two (2) kinds.

The first is known as compound crime, or when a

single act constitutes two or more grave or less

grave felonies. The second is known as complex

crime proper, or when an offense is a necessary

means for committing the other.

CONSIDERING OUR HOLDING ABOVE, WE RULE

THAT ACCUSED-APPELLANT ORIAS IS GUILTY, NOT

OF A COMPLEX CRIME OF MULTIPLE MURDER,

BUT OF THREE (3) COUNTS OF MURDER FOR THE

DEATH OF THE THREE (3) VICTIMS.

Since there was only one information filed

against accused-appellant Orias and Elarcosa,

the Court observes that there is duplicity of the

offenses charged in the said information. This is

a ground for a motion to quash as three (3)

separate acts of murder were charged in the

information. Nonetheless, the failure of accused-

appellant Orias to interpose an objection on this

ground constitutes waiver. 55

Albert vs. Sandiganbayan and People

Facts: That in (sic) or about May 1990 and

sometime prior or subsequent thereto, in the City

of Davao, Philippines and within the jurisdiction

of this Honorable Court, accused RAMON A.

ALBERT, a public officer, being then THE

PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL HOME MORTGAGE

AND FINANCE CORPORATION (NHMFC),

Consolidated case digests for Criminal Procedure

Maria Victoria Z. Matillano, Set 1 Final Half

occupying the said position with a salary grade

above 27, while in the performance of his official

function, committing the offense in relation to his

office, taking advantage of his official position,

conspiring and confederating with accused FAVIO

D. SAYSON, then the Project Director of CODE

Foundation Inc. and accused ARTURO S.

ASUMBRADO, then the President of the Buhangin

Residents and Employees Association for

Development, Inc., acting with evident bad faith

and manifest partiality and or gross neglect of

duty, did then and there willfully, unlawfully and

criminally cause undue injury to the government

and public interest, enter and make it appear in

Tax Declarations that two parcels of real

property particularly described in the Certificate

of Titles are residential lands which Tax

Declarations accused submitted to the NHMFC

when in truth and in fact, as accused well knew,

the two pieces of real property covered by

Certificate of Titles are agricultural land, and by

reason of accused's misrepresentation, the

NHMFC released the amount of P4,535,400.00

which is higher than the loanable amount the

land could command being agricultural, thus

causing undue injury to the government. On 18

December 2000, pending the resolution of the

Motion to Dismiss, petitioner filed a Motion to

Lift Hold Departure Order and to be Allowed to

Travel. The prosecution did not object to the

latter motion on the condition that petitioner

would be "provisionally" arraigned. 6 On 12

March 2001, petitioner filed an Urgent Motion to

Amend Motion to Lift Hold Departure Order and

to be Allowed to Travel. The following day, or on

13 March 2001, the Sandiganbayan arraigned

petitioner who entered a plea of "not guilty". In

the Resolution dated 16 April 2001, the

Sandiganbayan granted petitioner's Urgent

Motion to Amend Motion to Lift Hold Departure

Order and to be Allowed to Travel. On 26

November 2001, the Sandiganbayan denied

petitioner's Motion to Dismiss and ordered the

prosecution to conduct a reinvestigation of the

case with respect to petitioner. In a

Memorandum dated 6 January 2003, the SPO

who conducted the reinvestigation recommended

to the Ombudsman that the indictment against

petitioner be reversed for lack of probable cause.

However, the Ombudsman, in an Order dated 10

March 2003, disapproved the Memorandum and

directed the Office of the Special Prosecutor to

proceed with the prosecution of the criminal

case. Petitioner filed a Motion for

Reconsideration of the Order of the

Ombudsman.

In a Resolution promulgated on 16 May 2003, the

Sandiganbayan scheduled the arraignment of

petitioner on 24 July 2003. However, in view of

the pending motion for reconsideration of the

order of the Ombudsman, the arraignment was

reset to 2 October 2003. HAICTD

In a Manifestation dated 24 September 2003, the

SPO informed the Sandiganbayan of the

Ombudsman's denial of petitioner's motion for

reconsideration. On even date, the prosecution

filed an Ex-Parte Motion to Admit Amended

Information. During the 2 October 2003 hearing,

this ex-parte motion was withdrawn by the

prosecution with the intention of filing a Motion

for Leave to Admit Amended Information. The

scheduled arraignment of petitioner was reset to

1 December 2003. 7

On 7 October 2003, the prosecution filed a

Motion for Leave to Admit Amended Information.

THE RULING OF THE SANDIGANBAYAN

In its Resolution of 10 February 2004, 9 the

Sandiganbayan granted the prosecution's Motion

to Admit Amended Information. At the outset,

the Sandiganbayan explained that "gross neglect

of duty" which falls under Section 3 (f) of RA 3019

is different from "gross inexcusable negligence"

under Section 3 (e), and held thus:

In an information alleging gross neglect of duty, it

is not a requirement that such neglect or refusal

causes undue injury compared to an information

alleging gross inexcusable negligence where

undue effect constitutes substantial amendment

considering that the possible defense of the

accused may divert from the one originally

intended. ATDHSC

It may be considered however, that there are

three modes by which the offense for Violation of

Section 3(e) may be committed in any of the

following:

1. Through evident bad faith;

2. Through manifest partiality;

3. Through gross inexcusable negligence.

Proof of the existence of any of these modes in

connection with the prohibited acts under said

section of the law should suffice to warrant

conviction. 10

However, the Sandiganbayan also held that even

granting that the amendment of the information

be formal or substantial, the prosecution could

still effect the same in the event that the accused

had not yet undergone a permanent arraignment.

And since the arraignment of petitioner on 13

March 2001 was merely "provisional", then the

prosecution may still amend the information

either in form or in substance.

Consolidated case digests for Criminal Procedure

Maria Victoria Z. Matillano, Set 1 Final Half

Issues:

1. WHETHER THE SANDIGANBAYAN

GRAVELY ABUSED ITS DISCRETION

AMOUNTING TO LACK OR EXCESS OF

JURISDICTION IN ADMITTING THE

AMENDED INFORMATION.

2. WHETHER THE SANDIGANBAYAN

GRAVELY ABUSED ITS DISCRETION

AMOUNTING TO LACK OR EXCESS OF

JURISDICTION IN FURTHER PROCEEDING

WITH THE CASE DESPITE THE VIOLATION

OF THE RIGHT OF THE ACCUSED TO A

SPEEDY TRIAL.

Held:

1

st

ISSUE: The original information filed against

petitioner alleged that he acted with "evident bad

faith and manifest partiality and or (sic) gross

neglect of duty". The amended information, on

the other hand, alleges that petitioner acted with

"evident bad faith and manifest partiality and/or

gross inexcusable negligence". Simply, the

amendment seeks to replace "gross neglect of

duty" with "gross inexcusable negligence". Given

that these two phrases fall under different

paragraphs of RA 3019 specifically, "gross

neglect of duty" is under Section 3 (f) while "gross

inexcusable negligence" is under Section 3 (e) of

the statute the question remains whether or

not the amendment is substantial and prejudicial

to the rights of petitioner. The test as to when the

rights of an accused are prejudiced by the

amendment of a complaint or information is

when a defense under the complaint or

information, as it originally stood, would no

longer be available after the amendment is made,

and when any evidence the accused might have,

would be inapplicable to the complaint or

information as amended. 26 On the other hand,

an amendment which merely states with

additional precision something which is already

contained in the original information and which,

therefore, adds nothing essential for conviction

for the crime charged is an amendment to form

that can be made at anytime. 27 In this case, the

amendment entails the deletion of the phrase

"gross neglect of duty" from the Information.

ALTHOUGH THIS MAY BE CONSIDERED A

SUBSTANTIAL AMENDMENT, THE SAME IS

ALLOWABLE EVEN AFTER ARRAIGNMENT AND

PLEA BEING BENEFICIAL TO THE ACCUSED. 28 As

a replacement, "gross inexcusable negligence"

would be included in the Information as a

modality in the commission of the offense. This

Court believes that the same constitutes an

amendment only in form. The Court held that a

conviction for a criminal negligent act can be had

under an information exclusively charging the

commission of a willful offense upon the theory

that the greater includes the lesser offense.

2

nd

Issue: Petitioner's contentions are futile. This

right, however, is deemed violated only when the

proceeding is attended by vexatious, capricious,

and oppressive delays; or when unjustified

postponements of the trial are asked for and

secured; or when without cause or justifiable

motive a long period of time is allowed to elapse

without the party having his case tried. 32 A

simple mathematical computation of the period

involved is not sufficient. We concede that

judicial proceedings do not exist in a vacuum and

must contend with the realities of everyday life.

After reviewing the records of the case, we

believe that the right of petitioner to a speedy

trial was not infringed upon. The issue on the

inordinate delay in the resolution of the

complaint-affidavit filed against petitioner and his

co-accused and the filing of the original

Information against petitioner was raised in

petitioner's Motion to Dismiss, and was duly

addressed by the Sandiganbayan in its Resolution

denying the said motion. It appears that the said

delays were caused by the numerous motions for

extension of time to file various pleadings and to

reproduce documents filed by petitioner's co-

accused, and that no actual preliminary

investigation was conducted on petitioner.

Dino vs. OIlivarez

Petitioners instituted a complaint for vote buying

against respondent Pablo Olivarez. Based on the

finding of probable cause in the Joint Resolution

issued by Assistant City Prosecutor Antonietta

Pablo-Medina, with the approval of the city

prosecutor of Paraaque, two Informations were

filed before the RTC on 29 September 2004

charging respondent Pablo Olivarez with Violation

of Section 261, paragraphs a, b and k of Article

XXII of the Omnibus Election Code .

On 11 October 2004, respondent filed a Motion

to Quash the two criminal informations on the

ground that more than one offense was charged

therein, in violation of Section 3(f), Rule 117 of

the Rules of Court, in relation to Section 13, Rule

110 of the Rules of Court. This caused the

resetting of the scheduled arraignment on 18

October 2004 to 13 December 2004.

Consolidated case digests for Criminal Procedure

Maria Victoria Z. Matillano, Set 1 Final Half

Before Judge Madrona could act on the motion to

quash, Assistant Prosecutor Pablo-Medina, with

the approval of the city prosecutor, filed on 28

October 2004 its "Opposition to the Motion to

Quash and Motion to Admit Amended

Informations." The Amended Informations sought

to be admitted charged respondent with violation

of only paragraph a, in relation to paragraph b, of

Section 261, Article XXII of the Omnibus Election

Code. CEaDAc

On 1 December 2004, Judge Madrona issued an

Order resetting the hearing scheduled on 13

December 2004 to 1 February 2005 on account of

the pending Motion to Quash of the respondent

and the Amended Informations of the public

prosecutor.

On 14 December 2004, respondent filed an

"Opposition to the Admission of the Amended

Informations," arguing that no resolution was

issued to explain the changes therein, particularly

the deletion of paragraph k, Section 261, Article

XXII of the Omnibus Election Code. Moreover, he

averred that the city prosecutor was no longer

empowered to amend the informations, since the

COMELEC had already directed it to transmit the

entire records of the case and suspend the

hearing of the cases before the RTC until the

resolution of the appeal before the COMELEC en

banc.

On 12 January 2005, Judge Madrona issued an

order denying respondent's Motion to Quash

dated 11 October 2004, and admitted the

Amended Informations dated 25 October 2004.

Respondent filed an Urgent Motion for

Reconsideration dated 20 January 2005 thereon.

On 1 February 2005, Judge Madrona reset the

arraignment to 9 March 2005, with a warning that

the arraignment would proceed without any

more delay, unless the Supreme Court would

issue an injunctive writ. aCIHAD

On 9 March 2005, respondent failed to appear

before the RTC. Thereupon, Judge Madrona, in

open court, denied the Motion for

Reconsideration of the Order denying the Motion

to Quash and admitting the Amended

Informations, and ordered the arrest of

respondent and the confiscation of the cash

bond.

On 11 March 2005, respondent filed an "Urgent

Motion for Reconsideration and/or to Lift the

Order of Arrest of Accused Dr. Pablo Olivarez,"

which was denied in an Order dated 31 March

2005. The Order directed that a bench warrant be

issued for the arrest of respondent to ensure his

presence at his arraignment.

On 5 April 2005, the Law Department of the

COMELEC filed before the RTC a Manifestation

and Motion wherein it alleged that pursuant to

the COMELEC's powers to investigate and

prosecute election offense cases, it had the

power to revoke the delegation of its authority to

the city prosecutor.

Issue:

1. W/N court erred in ruling the admission

of the two amended informations and in

dismissing his motion to quash. (YES the

court erred)

2. W/N the city prosecutor defied the order

or directive of the COMELEC when it filed

the amended informations. (YES CP

acted in excess of his authority)

1. Held:

As it stands, since there are no amended

informations to speak of, the trial court has no

basis for denying respondent's motion to quash.

Consequently, there can be no arraignment on

the amended informations. In view of this, there

can be no basis for ordering the arrest of

respondent and the confiscation of his cash bond.

For having been issued with grave abuse of

discretion, amounting to lack or excess of

jurisdiction, the trial court's orders dated 12

January 2005 denying the Motion to Quash and

admitting the amended information; 9 March

2005 denying the Motion for Reconsideration of

the Order denying the Motion to Quash,

admitting the amended informations, and

ordering the arrest of the respondent and the

confiscation of his cash bond; and 31 March 2005

denying respondent's Urgent Motion for

Reconsideration and/or to lift the Order of Arrest

are declared void and of no effect. Motion for

Reconsideration is Granted/

2. Held:

It cannot also be disputed that the COMELEC Law

Department has the authority to direct, nay,

order the public prosecutor to suspend further

implementation of the questioned resolution

until final resolution of said appeal, for it is

speaking on behalf of the COMELEC. The

COMELEC Law Department, without any doubt, is

authorized to do this as shown by the pleadings it

has filed before the trial court. If the COMELEC

Law Department is not authorized to issue any

directive/order or to file the pleadings on behalf

of the COMELEC, the COMELEC En Banc itself

would have said so. This, the COMELEC En Banc

did not do.

Consolidated case digests for Criminal Procedure

Maria Victoria Z. Matillano, Set 1 Final Half

The records are likewise bereft of any evidence

showing that the City Prosecutor of Paraaque

doubted such authority. It knew that the

COMELEC Law Department could make such an

order, but the public prosecutor opted to

disregard the same and still filed the Amended

Informations contrary to the order to hold the

proceedings in abeyance until a final resolution of

said appeal was made by the COMELEC En Banc.

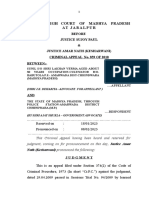

Lazarte vs. Sandiganbayan

Facts:

In June 1990, the National Housing Authority

(NHA) awarded the original contract for the

infrastructure works on the Pahanocoy Sites and

Services Project, Phase 1 in Bacolod City to A.C.

Cruz Construction. The project, with a contract

cost of P7,666,507.55, was funded by the World

Bank under the Project Loan Agreement forged

on 10 June 1983 between the Philippine

Government and the IBRD-World Bank.

A.C. Cruz Construction commenced the

infrastructure works on 1 August 1990. 5 In April

1991, the complainant Candido M. Fajutag, Jr.

(Fajutag, Jr.) was designated Project Engineer of

the project.

A Variation/Extra Work Order No. 1 was approved

for the excavation of unsuitable materials and

road filling works. As a consequence, Arceo Cruz

of A.C. Cruz Construction submitted the fourth

billing and Report of Physical Accomplishments

on 6 May 1991. Fajutag, Jr., however, discovered

certain deficiencies. As a result, he issued Work

Instruction No. 1 requiring some supporting

documents, such as: (1) copy of approved

concrete pouring; (2) survey results of original

ground and finished leaks; (3) volume calculation

of earth fill actually rendered on site; (4) test

results as to the quality of materials and

compaction; and (5) copy of work instructions

attesting to the demolished concrete structures.

The contractor failed to comply with the work

instruction. Upon Fajutag, Jr.'s further

verification, it was established that there was no

actual excavation and road filling works

undertaken by A.C. Cruz Construction.

On 2 October 2006, petitioner filed a motion to

quash the Information raising the following

grounds: (1) the facts charged in the information

do not constitute an offense; (2) the information

does not conform substantially to the prescribed

form; (3) the constitutional rights of the accused

to be informed of the nature and cause of the

accusations against them have been violated by

the inadequacy of the information; and (4) the

prosecution failed to determine the individual

participation of all the accused in the information

in disobedience with the Resolution dated 27

March 2005. 18

On 2 March 2007, the Sandiganbayan issued the

first assailed resolution denying petitioner's

motion to quash. We quote the said resolution in

part:

Among the accused-movants, the public officer

whose participation in the alleged offense is

specifically mentioned in the May 30, 2006

Memorandum is accused Felicisimo Lazarte, Jr.,

the Chairman of the Inventory and Acceptance

Committee (IAC), which undertook the inventory

and final quantification of the accomplishment of

A.C. Cruz Construction. The allegations of Lazarte

that the IAC, due to certain constraints, allegedly

had to rely on the reports of the field engineers

and/or the Project Office as to which materials

were actually installed; and that he supposedly

affixed his signature to the IAC Physical Inventory

Report and Memoranda dated August 12, 1991

despite his not being able to attend the actual

inspection because he allegedly saw that all the

members of the Committee had already signed

are matters of defense which he can address in

the course of the trial. Hence, the quashal of the

information with respect to accused Lazarte is

denied for lack of merit.

WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing, the Court

hereby resolves as follows:

(1) Accused Robert Balao, Josephine Angsico and

Virgilio Dacalos' Motion to Admit Motion to

Quash dated October 4, 2006 is GRANTED; the

Motion to Quash dated October 4, 2006 attached

thereto, is GRANTED. Accordingly, the case is

hereby DISMISSED insofar as the said accused-

movants are concerned.

(2) The Motion to Quash dated October 2, 2006

of accused Engr. Felicisimo F. Lazarte, Jr. is hereby

DENIED for lack of merit. Let the arraignment of

the accused proceed as scheduled on March 13,

2007.

Issues:

1. W/N the Information filed before the

Sandiganbayan insufficiently averred the

essential elements of the crime charged

Consolidated case digests for Criminal Procedure

Maria Victoria Z. Matillano, Set 1 Final Half

as it failed to specify the individual

participation of all the accused. NO

2. W/N the Sandiganbayan has jurisdiction

over the case. YES

Held: The Court is not persuaded. The Court

affirms the resolutions of the Sandiganbayan.

At the outset, it should be stressed that the denial

of a motion to quash is not correctible by

certiorari. Well-established is the rule that when a

motion to quash in a criminal case is denied, the

remedy is not a petition for certiorari but for

petitioners to go to trial without prejudice to

reiterating the special defenses invoked in their

motion to quash. Remedial measures as regards

interlocutory orders, such as a motion to quash,

are frowned upon and often dismissed. The

evident reason for this rule is to avoid multiplicity

of appeals in a single court. 31

This general rule, however, is subject to certain

exceptions. If the court, in denying the motion to

dismiss or motion to quash acts without or in

excess of jurisdiction or with grave abuse of

discretion, then certiorari or prohibition lies. 32

And in the case at bar, the Court does not find the

Sandiganbayan to have committed grave abuse of

discretion.

The fundamental test in reflecting on the viability

of a motion to quash on the ground that the facts

charged do not constitute an offense is whether

or not the facts asseverated, if hypothetically

admitted, would establish the essential elements

of the crime defined in law. 33 Matters aliunde

will not be considered.

Finally, the Court sustains the Sandiganbayan's

jurisdiction to hear the case. As correctly pointed

out by the Sandiganbayan, it is of no moment that

petitioner does not occupy a position with Salary

Grade 27 as he was a department manager of the

NHA, a government-owned or controlled

corporation, at the time of the commission of the

offense, which position falls within the ambit of

its jurisdiction.

The instant petition is DISMISSED. The

Resolutions dated 2 March 2007 and 18 October

2007 of the First Division of the Sandiganbayan

are AFFIRMED.

ALAWIYA y ABDUL vs. CA

Facts: On 18 September 2001, petitioners

executed sworn statements4 before the General

Assignment Section of the Western Police District

in United Nations Avenue, Manila, charging

accused P/C Insp. Michael Angelo Bernardo

Martin, P/Insp. Allanjing Estrada Medina, PO3

Arnold Ramos Asis, PO2 Pedro Santos Gutierrez,

PO2 Ignacio De Paz and PO2 Antonio Sebastian

Berida, Jr., who were all policemen assigned at

that time at the Northern Police District, with

kidnapping for ransom. The sworn-statements of

petitioners commonly alleged that at about 10:00

in the morning of 11 September 2001, while

petitioners were cruising on board a vehicle along

United Nations Avenue, a blue Toyota Sedan

bumped their vehicle from behind; that when

they went out of their vehicle to assess the

damage, several armed men alighted from the

Toyota Sedan, poked guns at, blindfolded, and

forced them to ride in the Toyota Sedan; that

they were brought to an office where

P10,000,000 and two vehicles were demanded

from them in exchange for their freedom; that,

after haggling, the amount was reduced to

P700,000 plus the two vehicles; that the money

and vehicles were delivered in the late evening of

11 September 2001; that they were released in

the early morning of 12 September 2001 in

Quiapo after they handed the Deed of Sale and

registration papers of the two vehicles.

On 24 January 2002, State Prosecutor Velasco

filed with the RTC of Manila an Information for

Kidnapping for Ransom against the accused with

no bail recommended.

On 28 January 2002, the trial court, upon motion

by the prosecution, issued a Hold Departure

Order against the accused.9 On even date, the

trial court issued a Warrant of Arrest against all

the accused.10

Meanwhile, on 8 February 2002, the accused filed

a petition for review of the Resolution of State

Prosecutor Velasco with the Office of the

Secretary of Justice.

On 18 February 2002, the accused moved for the

quashal of the Information on the ground that

"the officer who filed the Information has no

authority do so."11

Issue: Whether the accused policemen can seek

any relief (via a motion to quash the information)

from the trial court when they had not been

arrested yet.

Held: NO. At any rate, the accuseds motion to

quash, on the ground of lack of authority of the

filing officer, would have never prospered

Consolidated case digests for Criminal Procedure

Maria Victoria Z. Matillano, Set 1 Final Half

because as discussed earlier, the Ombudsmans

power to investigate offenses involving public

officers or employees is not exclusive but is

concurrent with other similarly authorized

agencies of the government.

When the accused had not been arrested yet

People v. Mapalao,27 as correctly argued by the

OSG, does not squarely apply to the present

case. In that case, one of the accused, Rex

Magumnang, after arraignment and during the

trial, escaped from detention and had not been

apprehended since then. Accordingly, as to him

the trial in absentia proceeded and thereafter the

judgment of conviction was promulgated. The

Court held that since the accused remained at

large, he should not be afforded the right to

appeal from the judgment of conviction unless he

voluntarily submits to the jurisdiction of the court

or is otherwise arrested. While at large, the

accused cannot seek relief from the court as he is

deemed to have waived the same and he has no

standing in court.28 In Mapalao, the accused

escaped while the trial of the case was on-going,

whereas here, the accused have not been served

the warrant of arrest and have not been

arraigned. Therefore, Mapalao is definitely not on

all fours with the present case.lavvphil.net

Furthermore, there is nothing in the Rules

governing a motion to quash29 which requires

that the accused should be under the custody of

the law prior to the filing of a motion to quash on

the ground that the officer filing the information

had no authority to do so. Custody of the law is

not required for the adjudication of reliefs other

than an application for bail.30 However, while the

accused are not yet under the custody of the law,

any question on the jurisdiction over the person

of the accused is deemed waived by the accused

when he files any pleading seeking an affirmative

relief, except in cases when the accused invokes

the special jurisdiction of the court by impugning

such jurisdiction over his person.

There is no clear showing that the present case

falls under any of the recognized exceptions.

Moreover, as stated earlier, once the information

is filed with the trial court, any disposition of the

information rests on the sound discretion of the

court. The trial court is mandated to

independently evaluate or assess the existence of

probable cause and it may either agree or

disagree with the recommendation of the

Secretary of Justice. The trial court is not bound

to adopt the resolution of the Secretary of

Justice.34 Reliance alone on the resolution of the

Secretary of Justice amounts to an abdication of

the trial courts duty and jurisdiction to determine

the existence of probable cause.35

Considering that the Information has already

been filed with the trial court, then the trial court,

upon filing of the appropriate motion by the

prosecutor, should be given the opportunity to

perform its duty of evaluating, independently of

the Resolution of the Secretary of Justice

recommending the withdrawal of the Information

against the accused, the merits of the case and

assess whether probable cause exists to hold the

accused for trial for kidnapping for ransom.36

WHEREFORE, we REMAND this case to the

Regional Trial Court, Branch 41, Manila, to

independently evaluate or assess the merits of

the case to determine whether probable cause

exists to hold the accused for trial.

Los Banos vs. Pedro

The petition seeks to revive the case against

respondent Joel R. Pedro (Pedro) for election gun

ban violation after the CA declared the case

permanently dismissed pursuant to Section 8,

Rule 117 of the Rules of Court.

Pedro was charged in court for carrying a loaded

firearm without the required written

authorization from the Commission on Elections

(Comelec) a day before the May 14, 2001 national

and local elections.

The accusation was based on Batas Pambansa

Bilang 881 or the Omnibus Election Code (Code)

after the Marinduque Philippine National Police

(PNP) caught Pedro illegally carrying his firearm at

a checkpoint at Boac, Marinduque.

Pedro filed a Motion for Preliminary Investigation,

which the RTC granted. 7 The preliminary

investigation, however, did not materialize.

Instead, Pedro filed with the RTC a Motion to

Quash, arguing that the Information "contains

averments which, if true, would constitute a legal

excuse or justification 8 and/or that the facts

charged do not constitute an offense." 9 Pedro

attached to his motion a Comelec Certification

dated September 24, 2001 that he was

"exempted" from the gun ban. The provincial

prosecutor opposed the motion.

The RTC quashed the Information and ordered

the police and the prosecutors to return the

seized articles to Pedro. 10 IHCSET

The petitioner, private prosecutor Ariel Los Baos

(Los Baos), representing the checkpoint team,

moved to reopen the case, as Pedro's Comelec

Certification was a "falsification", and the

prosecution was "deprived of due process" when

Consolidated case digests for Criminal Procedure

Maria Victoria Z. Matillano, Set 1 Final Half

the judge quashed the information without a

hearing. Attached to Los Baos' motion were two

Comelec certifications stating that: (1) Pedro was

not exempted from the firearm ban; and (2) the

signatures in the Comelec Certification of

September 24, 2001 were forged.

The RTC reopened the case for further

proceedings, as Pedro did not object to Los

Baos' motion. 11 Pedro moved for the

reconsideration of the RTC's order primarily

based on Section 8 of Rule 117, 12 arguing that

the dismissal had become permanent. He likewise

cited the public prosecutor's lack of express

approval of the motion to reopen the case.

THE COURT OF APPEALS DECISION

The CA initially denied Pedro's petition. For

accuracy, we quote the material portions of its

ruling: The petition lacks merit.

To summarize this ruling, the appellate court,

while initially saying that there was an error of

law but no grave abuse of discretion that would

call for the issuance of a writ, reversed itself on

motion for reconsideration; it then ruled that the

RTC committed grave abuse of discretion because

it failed to apply Section 8, Rule 17 and the time-

bar under this provision.

Issue: The issue is ultimately reduced to whether

Section 8, Rule 117 is applicable to the case, as

the CA found. If it applies, then the CA ruling

effectively lays the matter to rest. If it does not,

then the revised RTC decision reopening the case

should prevail.

Held: We find the petition meritorious and hold

that the case should be remanded to the trial

court for arraignment and trial.

In People v. Lacson, 21 we ruled that there are

sine qua non requirements in the application of

the time-bar rule stated in the second paragraph

of Section 8 of Rule 117. We also ruled that the

time-bar under the foregoing provision is a

special procedural limitation qualifying the right

of the State to prosecute, making the time-bar

an essence of the given right or as an inherent

part thereof, so that the lapse of the time-bar

operates to extinguish the right of the State to

prosecute the accused.

c. Their Comparison

An examination of the whole Rule tells us that a

dismissal based on a motion to quash and a

provisional dismissal are far different from one

another as concepts, in their features, and legal

consequences. While the provision on

provisional dismissal is found within Rule 117

(entitled Motion to Quash), it does not follow

that a motion to quash results in a provisional

dismissal to which Section 8, Rule 117 applies. A

first notable feature of Section 8, Rule 117 is that

it does not exactly state what a provisional

dismissal is. The modifier "provisional" directly

suggests that the dismissals which Section 8

essentially refers to are those that are temporary

in character (i.e., to dismissals that are without

prejudice to the re-filing of the case), and not the

dismissals that are permanent (i.e., those that bar

the re-filing of the case). Based on the law, rules,

and jurisprudence, permanent dismissals are

those barred by the principle of double jeopardy,

22 by the previous extinction of criminal liability,

23 by the rule on speedy trial, 24 and the

dismissals after plea without the express consent

of the accused. 25 Section 8, by its own terms,

cannot cover these dismissals because they are

not provisional. A second feature is that Section 8

does not state the grounds that lead to a

provisional dismissal. This is in marked contrast

with a motion to quash whose grounds are

specified under Section 3. The delimitation of the

grounds available in a motion to quash suggests

that a motion to quash is a class in itself, with

specific and closely-defined characteristics under

the Rules of Court. A necessary consequence is

that where the grounds cited are those listed

under Section 3, then the appropriate remedy is

to file a motion to quash, not any other remedy.

Conversely, where a ground does not appear

under Section 3, then a motion to quash is not a

proper remedy. A motion for provisional dismissal

may then apply if the conditions required by

Section 8 obtain. AHCcET

A third feature, closely related to the second,

focuses on the consequences of a meritorious

motion to quash. This feature also answers the

question of whether the quashal of an

information can be treated as a provisional

dismissal. Sections 4, 5, 6, and 7 of Rule 117

unmistakably provide for the consequences of a

meritorious motion to quash. Section 4 speaks of

an amendment of the complaint or information, if

the motion to quash relates to a defect curable by

amendment. Section 5 dwells on the effect of

sustaining the motion to quash the complaint

or information may be re-filed, except for the

instances mentioned under Section 6. The latter

section, on the other hand, specifies the limit of

the re-filing that Section 5 allows it cannot be

Consolidated case digests for Criminal Procedure

Maria Victoria Z. Matillano, Set 1 Final Half

done where the dismissal is based on extinction

of criminal liability or double jeopardy. Section 7

defines double jeopardy and complements the

ground provided under Section 3 (i) and the

exception stated in Section 6.

The failure of the Rules to state under Section 6

that a Section 8 provisional dismissal is a bar to

further prosecution shows that the framers did

not intend a dismissal based on a motion to

quash and a provisional dismissal to be confused

with one another; Section 8 operates in a world

of its own separate from motion to quash, and

merely provides a time-bar that uniquely applies

to dismissals other than those grounded on

Section 3Conversely, when a dismissal is pursuant

to a motion to quash under Section 3, Section 8

and its time-bar does not apply.

To recapitulate, quashal and provisional dismissal

are different concepts whose respective rules

refer to different situations that should not be

confused with one another. If the problem relates

to an intrinsic or extrinsic deficiency of the

complaint or information, as shown on its face,

the remedy is a motion to quash under the terms

of Section 3, Rule 117. All other reasons for

seeking the dismissal of the complaint or

information, before arraignment and under the

circumstances outlined in Section 8, fall under

provisional dismissal.

Thus, we conclude that Section 8, Rule 117 does

not apply to the reopening of the case that the

RTC ordered and which the CA reversed; the

reversal of the CA's order is legally proper.

The grounds Pedro cited in his motion to quash

are that the Information contains averments

which, if true, would constitute a legal excuse or

justification [Section 3 (h), Rule 117], and that the

facts charged do not constitute an offense

[Section 3 (a), Rule 117]. We find from our

examination of the records that the Information

duly charged a specific offense and provides the

details on how the offense was committed. 28

Thus, the cited Section 3 (a) ground has no merit.

On the other hand, we do not see on the face or

from the averments of the Information any legal

excuse or justification. The cited basis, in fact, for

Pedro's motion to quash was a Comelec

Certification (dated September 24, 2001, issued

by Director Jose P. Balbuena, Sr. of the Law

Department, Committee on Firearms and Security

Personnel of the Comelec, granting him an

exemption from the ban and a permit to carry

firearms during the election period) 29 that Pedro

attached to his motion to quash. This COMELEC

Certification is a matter aliunde that is not an

appropriate motion to raise in, and cannot

support, a motion to quash grounded on legal

excuse or justification found on the face of the

Information. Significantly, no hearing was ever

called to allow the prosecution to contest the

genuineness of the COMELEC certification. 30

aATEDS

Thus, the RTC grossly erred in its initial ruling

that a quashal of the Information was in order.

Pedro, on the other hand, also misappreciated

the true nature, function, and utility of a motion

to quash. As a consequence, a valid Information

still stands, on the basis of which Pedro should

now be arraigned and stand trial.

You might also like

- Malachite GreenDocument5 pagesMalachite GreenChern YuanNo ratings yet

- Case Study #3Document4 pagesCase Study #3Annie Morrison AshtonNo ratings yet

- Rule XIX 2009 DARAB Rules of ProcedureDocument2 pagesRule XIX 2009 DARAB Rules of ProcedureavrilleNo ratings yet

- MS 1 - 3 ReportDocument19 pagesMS 1 - 3 ReportNauman Mithani100% (1)

- CommRev FRIA CasesDocument23 pagesCommRev FRIA CasesCarene Leanne BernardoNo ratings yet

- Lao Vs CA: 119178: June 20, 1997Document16 pagesLao Vs CA: 119178: June 20, 1997Re doNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Suspends Lawyer for Failing to Transfer Property Title and Return Client FundsDocument13 pagesSupreme Court Suspends Lawyer for Failing to Transfer Property Title and Return Client Fundsclaire beltranNo ratings yet

- Life Is Beautiful: SummaryDocument5 pagesLife Is Beautiful: SummarymissalaineNo ratings yet

- Diamond V ChakrabartyDocument7 pagesDiamond V ChakrabartyIndiraNo ratings yet

- Bio-Zoology - Vol - 2 EM PDFDocument176 pagesBio-Zoology - Vol - 2 EM PDFmuraliNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument9 pagesIntroductionTonton ReyesNo ratings yet

- 109 Republic v. KatigbakDocument4 pages109 Republic v. KatigbakLizanne GauranaNo ratings yet

- Art AppreciationDocument28 pagesArt Appreciationbea0% (1)

- Spouses Tan Vs China Banking CorpDocument6 pagesSpouses Tan Vs China Banking CorpmichelledugsNo ratings yet

- Judge Ordered Release of Seized Rice Despite Pending CaseDocument6 pagesJudge Ordered Release of Seized Rice Despite Pending CasefilamiecacdacNo ratings yet

- Revision of Philippine Marine Pollution LawDocument3 pagesRevision of Philippine Marine Pollution LawNichole Patricia PedriñaNo ratings yet

- E12 Yeast Metabolism PostlabDocument4 pagesE12 Yeast Metabolism PostlabaraneyaNo ratings yet

- Rule 116Document20 pagesRule 116Leslie Ann DestajoNo ratings yet

- Essay On Air PollutionDocument1 pageEssay On Air PollutionJasvinder SinghNo ratings yet

- Dennis Gabionza Vs CADocument2 pagesDennis Gabionza Vs CAanailabucaNo ratings yet

- MMDA V Concerned Residents of Manila Bay (Environmental Law)Document16 pagesMMDA V Concerned Residents of Manila Bay (Environmental Law)OpsOlavarioNo ratings yet

- Deposit-Trust Receipts Compilation - BPI Vs IAC To Rosario TextileDocument16 pagesDeposit-Trust Receipts Compilation - BPI Vs IAC To Rosario Textile001nooneNo ratings yet

- Nippon Paint Employees Union-Olalia v. Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesNippon Paint Employees Union-Olalia v. Court of AppealsTJ CortezNo ratings yet

- Twentieth Century Music Corporation v. George Aiken, 422 U.S. 151 (1975)Document15 pagesTwentieth Century Music Corporation v. George Aiken, 422 U.S. 151 (1975)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chapter-2: Preparation of Samples For AnalysisDocument14 pagesChapter-2: Preparation of Samples For AnalysisAgegnehu TakeleNo ratings yet

- Corp. Case DigestDocument10 pagesCorp. Case DigestAldrin John Joseph De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- International Corporate Bank vs. GuecoDocument5 pagesInternational Corporate Bank vs. Guecopreiquency100% (1)

- Provisional Remedies GuideDocument30 pagesProvisional Remedies GuideJuno GeronimoNo ratings yet

- Zero Waste PRACRESEARCHDocument13 pagesZero Waste PRACRESEARCHSai ImboNo ratings yet

- Republic Act No 9745Document4 pagesRepublic Act No 9745Jonald Ritual BuendichoNo ratings yet

- Citihomes retains right to evict despite assignmentDocument10 pagesCitihomes retains right to evict despite assignmentPaolo Enrino PascualNo ratings yet

- In RE Atty Melchor RusteDocument5 pagesIn RE Atty Melchor RusteLeidi Chua BayudanNo ratings yet

- CRISTOBAL BONNEVIE, ET AL., Plaintiffs-Appellants, vs. JAIME HERNANDEZ, Defendant-Appellee. G.R. No. L-5837 FactsDocument2 pagesCRISTOBAL BONNEVIE, ET AL., Plaintiffs-Appellants, vs. JAIME HERNANDEZ, Defendant-Appellee. G.R. No. L-5837 FactsMayoree FlorencioNo ratings yet