Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Pain Education Programme

Uploaded by

api-2442306640 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

68 views13 pagesOriginal Title

a pain education programme

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

68 views13 pagesA Pain Education Programme

Uploaded by

api-244230664Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 13

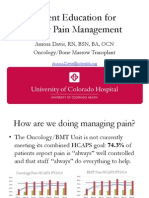

PAI N MANAGEMENT

A pain education programme to improve patient satisfaction with

cancer pain management: a randomised control trial

Pi-Ling Chou and Chia-Chin Lin

Aim. The purpose of this study was (1) to evaluate the effectiveness of a pain education programme to increase the satisfaction

of patients with cancer with regard to pain management and (2) to examine how patient satisfaction with pain management

mediates the barriers to using analgesics and analgesic adherence.

Background. The patients satisfaction with pain management is not merely an indicator, it is actually a contributor to med-

ication adherence. However, very few studies investigate methods for improving patient satisfaction with pain management.

Design. This study used an experimental and longitudinal design.

Methods. A total of 61 patientfamily pairs (n = 122) were randomly assigned to either experimental or control groups. The

instruments included the American Pain Society outcome questionnaire, the Barriers Questionnaire-Taiwan form, self-reporting

evaluations of analgesic adherence and the Pain Education Booklet. The experimental group (n = 31) participated in a pain

education programme, while those in the control group (n = 30) did not. The two groups were compared using generalised

estimation equations after the second and fourth weeks. A Sobel test was used to examine the mediating relationships among

patient satisfaction with pain management, barriers to using analgesics and analgesic adherence.

Results. The experimental group showed a signicant improvement in the level of satisfaction they felt for physicians and nurses

regarding pain management. For those in the experimental group, satisfaction with pain management was a signicant mediator

between barriers to using analgesics and analgesic adherence.

Conclusions. This research provides evidence supporting the effectiveness of a pain education programme for patients and their

family members in increasing patient satisfaction with regard to the management of cancer pain.

Relevance to clinical practice. It is important for health providers to consider patient satisfaction when attempting to improve

adherence to pain management regimes in a clinical setting.

Key words: barriers to pain management, cancer pain, mediator, nurses, nursing, pain education programme, pain management,

patient satisfaction

Accepted for publication: 9 January 2011

Introduction

Cancer pain is a serious clinical problem and improving the

means by which it is treated is an issue of critical importance

(Gordon et al. 2002, Jain et al. 2008). Assuring the quality of

cancer pain management by systematically evaluating the

methods employed in such treatment can enhance the effec-

tiveness of pain control in patients with cancer (Ward et al.

1998). The patients satisfaction with pain control is an

essential indicator in assessing the quality of cancer pain

management (Sterman et al. 2003, Panteli & Patistea 2007);

however, very few researchers have adopted a longitudinal

Authors: Pi-Ling Chou, MS, RN, Doctoral Student, Graduate

Institute of Nursing, College of Nursing, Taipei Medical University;

Chia-Chin Lin, PhD, RN, Professor and Director, School of Nursing,

College of Nursing, Taipei Medical University and Wan-Fang

Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan

Correspondence: Chia-Chin Lin, Professor and Director, School of

Nursing, College of Nursing, Taipei Medical University, No.250,

Wuxing St., Taipei 11031, Taiwan. Telephone: + 886 2 2377 6229.

E-mail: clin@tmu.edu.tw

1858 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 18581869

doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03740.x

approach to studying pain education as it pertains to this

issue. Patient satisfaction with pain control is not merely an

important indicator. If patients are more satised with their

pain management, they more likely to comply with the advice

of health providers (Hirsh et al. 2005). Previous studies

related to pain intervention have focused on barriers to

changing analgesics and the resulting inuence on patient

adherence to such treatment (Lin et al. 2006, Syrjala et al.

2008). Unfortunately, the means by which these barriers

inuence adherence remains unclear. A deeper under-

standing of the mechanisms involved in patient satisfaction

that dissuade patients from adhering to the prescribed use

of analgesics could prove extremely valuable in clinical

practice.

Background

Patient satisfaction towards their treatment was dened by

Lebow (1982) as the extent to which treatment graties the

wants, wishes and desires of clients. Several studies have

adopted the satisfaction that patients feel towards pain

management as an indicator for assessing the effectiveness of

pain management (de Wit et al. 2001, Jain et al. 2008).

Merkouris et al. (1999) reported that patient satisfaction

might provide the means to evaluate outcomes and act as a

contributor to other outcomes (i.e. adherence), inuencing

the process of recovery. Several researchers have discovered

that patient satisfaction with medical management could be

used to forecast medical outcomes, in addition to acting as an

outcome indicator (Meakin & Weinman 2002). For instance,

studies focusing on older patients suffering from coronary

heart disease discovered that the degree to which patients

adhere to the instructions they received regarding their

medication improves proportionally to the patients satisfac-

tion feel towards an increase in medical management from

their physicians and nurses (Rich et al. 1996, Rybacki 2002,

Simpson et al. 2002). Similarly, if the adherence of patients

increases with medical management, studies could more

accurately predict the outcome of health care services. Most

researchers recognise that patientprovider relationships and

patient satisfaction with those relationships are important

factors in adherence to treatment regimes (Cameron 1996,

Bos et al. 2005). One study indicated that the more satised

patients are with their pain management, the more they

comply with the advice of health care providers (Hirsh et al.

2005). Another study on chronic pain in children revealed

that the satisfaction of parents and children is signicantly

correlated with patient adherence (Simons et al. 2010).

Interventions that improve patient satisfaction could have a

positive inuence on the outcome of treatment for cancer pain.

Adherence to analgesic regimens has become one of the

most signicant clinical problems in the management of

cancer pain (Miaskowski et al. 2001). The lack of adher-

ence to analgesics is a result of myths regarding their use

(Tzeng et al. 2008, Valeberg et al. 2008). In the past few

decades, promoting and maintaining adherence to prescribed

analgesic regimens has become an important intervention in

the treatment of patients with cancer (Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality 2001). As a result, many studies have

developed strict guidelines to ameliorate misconceptions

regarding pain and analgesics, and several of these interven-

tions have signicantly increased patient adherence to the

prescriptions of medical personnel (Ferrell et al. 1993, Lin

et al. 2006, Syrjala et al. 2008). Patients who had been

educated concerning pain intervention were less likely to self-

terminate their medication when the pain decreased. Pain

education programmes appear to be benecial in reducing

patient misconceptions regarding analgesics and improving

patient adherence to their analgesic regimens.

The cancer patients satisfaction feel towards pain manage-

ment programmes is a relatively new topic of discussion and

many of the implications are scarcely understood (Alalo &

Tselios 1996, Sherwood et al. 2000). Evaluating the level of

patients satisfaction with the management of their cancer

pain can provide a deeper understanding of their general

satisfaction with the treatment they receive from their

physicians and nurses. In a study by Sherwood et al.

(2000), patients with cancer who were dissatised with their

pain management perceived a lack of empathy among health

care professionals, who were slow to respond to their

complaints of pain. In addition, the same patients believed

that health care professionals did not have sufcient knowl-

edge or the skills required to properly manage their pain.

Dissatisfaction with pain management may be a reection of

poor pain management provided by health care professionals

(Sherwood et al. 2000).

Several studies have shown that interventions encourage

patients with cancer to overcome the barriers preventing

them from adhering to analgesics meant to reduce their pain.

However, the mechanisms involved in the reduction of such

barriers have never been explored. This study suggests that

patient satisfaction with pain management regimes is a

signicant factor inuencing medication adherence and fully

exploring these underlying mechanisms is crucial. This study

hypothesises that long-term education programmes address-

ing the issue of cancer pain management for patients and

their families would improve patient satisfaction. Patient

satisfaction with pain management could be a signicant

mediating factor among the various barriers to using anal-

gesics and analgesic adherence.

Pain management Pain education to improve pain management

2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 18581869 1859

Methods

Participants and settings

This study, part of which has been published elsewhere (Lin

et al. 2006), is one component of a large randomised control

study. It was conducted in the oncology outpatient clinics of

two hospitals in Taipei, Taiwan. A purposive sample

consisting of outpatients and their primary caregivers was

recruited. Patientfamily pairs enrolled in the study were

randomly assigned to the experimental group or control

group using a computer-generated randomisation scheme

developed by the researcher. Random allocation sequences

and sealed, opaque envelopes were used to ensure security.

Two participants in the experimental group and two partic-

ipants in the control group discontinued involvement in the

study during the second assessment and three participants

stopped treatment after the third assessment. Sixty-one

patientfamily pairs (n = 122) completed the analysis, of

which 31 pairs were in the experimental group and 30 pairs

were in the control group (Fig. 1). Participants had to meet

the following criteria: (1) diagnosed with cancer; (2) expe-

riencing pain due to cancer and currently taking oral

analgesics; (3) over 18 years of age; and (4) ability to

communicate in Mandarin or Taiwanese. Participants suffer-

ing from cognitive impairment or brain metastasis were

excluded from the study. This study used SSIZE SSIZE software

(Hsieh 1991) to estimate the size of the sample from the pilot

study. Scores regarding patient satisfaction were used as the

primary outcome; with a r value of 005 and a test power of

85%. Satisfaction scores in the pretest were 35 (slightly

dissatised) and after two weeks 45 (somewhat satised).

Each group had to be maintained at 30 samples with a

difference of 1 between the two groups.

Instruments

The American Pain Society (APS) outcome questionnaire

The APS outcome questionnaire was developed from qual-

ity assurance studies, using identical tools for exploring

patient satisfaction with regard to the treatment of cancer-

related pain (Ward & Gordon 1994, Miaskowski et al.

1994). The standards proposed by the Quality Assurance

Committee of the APS were adopted in the development of

the questionnaire used in this study. In addition, the views

of patients regarding the means by which their doctors and

nurses managed their pain were also included (Max et al.

1991, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research 1994).

The questionnaire was translated into Mandarin using a

translation and back-translation method to ensure accuracy.

This questionnaire included three parts: (1) a patient

assessment of their satisfaction with the method of pain

management employed by their physician(s); (2) a patient

assessment of their satisfaction with the method of pain

management employed by their nurse(s); (3) a patient

assessment of their satisfaction with the overall treatment

they received for the management of their pain. This study

was scored on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 6 for

very satised 1 for very dissatised to establish reli-

ability and validity (Lin 2000, Panteli & Patistea 2007).

The Barriers Questionnaire-Taiwan form (BQT)

Ward and Colleagues proposed the Barriers Questionnaire

(BQ), which was specically developed to measure barriers to

the use of analgesics in patients with cancer (Ward et al.

1993). The BQT was translated and modied specically for

Taiwanese participants. It comprises nine subscales with 34

items (Lin & Ward 1995). Based on the results of content

analysis of the Taiwanese population, several items were

added to the BQT. The subscale of fear of injection was

dropped; and a three-item subscale labelled religious fatal-

ism was added. Another three-item subscale labelled P.R.N.

was also added. The nal BQT consisted of nine subscales,

Declined participation

(n = 19)

Not interested (n = 10)

Felt too burdensome (n = 4)

Other reasons (n = 5)

Randomised (n = 68)

Allocated to the

experimental group

(n = 34)

Allocated to the

control group

(n = 34)

Completed

assessment at T1

(n = 34)

Complete follow up at

T2 (n = 32)

Too ill (n = 2)

Completed

assessment at T1

(n = 34)

Complete follow up at

T2 (n = 32)

Transferred to hospice ward (n = 1)

Did not wish to continue (n = 1)

Complete follow up at

T3 (n = 31) Did not

wish to continue (n = 1)

Complete follow up at

T3 (n = 30)

Died (n = 1)

Missed because researcher

was unavailable (n = 1)

Assessed for eligibility

(n = 87)

Figure 1 Flow chart of the trial.

P-L Chou and C-C Lin

1860 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 18581869

with 34 items (Lin 2001). These subscales included the fol-

lowing: (1) addiction (three items); (2) disease progression

(three items); (3) pain tolerance (three items); (4) fatalism

(three items); (5) religious fatalism (three items); (6) P.R.N. or

as needed (three items); (7) concern about side effects

(10 items); (8) fear of distracting physicians (three items); and

(9) a desire to be good (three items). The BQT asks patients to

rate the extent to which they agree with each item on a scale

from 0 (do not agree at all) 5 (agree very much). This study

used both subscale scores and total score in the analyses. The

reliability and validity of the BQT were previously estab-

lished (Chang et al. 2002, Lin et al. 2006).

The Taiwanese version of the Morisky Medication Adherence

Measure (MMAM-T)

A structured four-item self-reporting measure of analgesic

adherence developed by Morisky et al. (1986) was adminis-

tered to patients to measure their compliance with analgesics.

The theory underlying this measure is that errors of drug

omission can occur for any or all of the following reasons:

forgetfulness, carelessness, cessation of the drug when feeling

better and use of the drug when feeling worse. The sum of the

yes answers provided a composite measure of non-adher-

ence. The total score ranged from 04, with higher scores

indicating a greater degree of adherence. The group showing

a high degree of adherence received a total score of 4; the

group with moderate adherence received a score of 23 and

the group with low adherence received a score of 01. A

Taiwanese sample with cancer pain veried the reliability and

concurrent construct validity of this measure (Tzeng et al.

2008).

Brief Pain Inventory-Chinese version (BPI-C)

This study uses the BPI-C version to measure the intensity of

pain and the degree to which pain interfered with daily

activities (Wang et al. 1996). The rst part of the BPI com-

prised the following four, single-item measures of pain

intensity, with each item rated on a scale of 0 (no pain) 10

(the worst pain I can imagine): (1) worst pain, (2) least pain,

(3) average pain and (4) pain now. A Taiwanese sample with

cancer pain established the reliability and validity of this

measure (Wang et al. 1996, Lin et al. 2006, Tsai et al. 2007).

The Pain Education Booklet

The primary researcher in this study developed the Pain

Education Booklet using concise descriptions and illustra-

tions to provide important information specic to Taiwanese

patients with cancer and their family caregivers, addressing

concerns of reporting pain and using analgesics. This pocket-

sized booklet is 16 pages long and addresses nine common

concerns. A panel of experts validated the content of the Pain

Education Booklet. Further modications to the content of

this booklet were made according to comments from patients

and experts. Cancer outpatients previously used this booklet in a

pain education programme (Chang et al. 2002, Lin et al. 2006).

Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS)

This study used the KPS to assess the performance status of

patients. The KPS is rated on a scale of 1100, in steps of 10.

The KPS has demonstrated a high level of predictive validity

(Buccheri et al. 1996).

Procedure

A research assistant approached patientfamily groups to

describe the study and obtain informed consent. On the day of

the rst interview, the patients in the experimental group lled

out the APS outcome questionnaire, the BQT, the BPI-C and

the self-reported measure of analgesics. They also ll out a

demographic questionnaire. After the patients had completed

the questionnaire, the research assistant provided a pain

education intervention session for patients and family caregiv-

ers, using the Pain Education Booklet. Researchers conducted

the session in a private room at the outpatient unit, to avoid

interruptions. The research assistant discussed all of the

content covered by the booklet and encouraged patients and

family caregivers to ask questions. The pain education session

took approximately 3040 minutes to complete. Patients and

family caregivers were encouraged to call phone numbers

included the booklet, following the education session, if they

required answers to any questions. Each participant received a

copy of the pain education booklet. The second and third

interviews were conducted two and four weeks after the pain

education session, respectively. At each interview, the patients

were asked to complete the questionnaire again. Researchers

took the chance to answer any questions the patients or family

caregivers had and reviewed the information on pain educa-

tion. Patients and their family caregivers in the control group

received conventional care. Patients in the control group

individually and independently completed the questionnaires

on pain and demographic data during the rst interview. They

complete the questionnaires during the two- and four-week

follow-up interviews. The control group did not receive an

education programme. The research assistant only answered

questions asked by patients or family caregivers. If the

interviewer observed that a patient appears to be in pain or

distress, or if a patient verbalised pain or distress, the

assessment or follow-up would cease until the patient was

relieved fromthese symptoms. Noadverse events or side effects

resulted from the intervention.

Pain management Pain education to improve pain management

2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 18581869 1861

Data analysis

This study used complete analysis to interpret the collected

data. The generalised estimating equations (GEE) analyses

the effects of the pain education programme on patient

satisfaction, and the Sobel test under the SAS SAS system (version

8.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) assesses the mediating

role on the barriers to using analgesics and analgesic adher-

ence. To account for repeated measurement dependence that

might occur at the two- and four-week intervals (Liang &

Zeger 1986, Zeger & Liang 1992, Lin et al. 2006), GEE were

used to analyse whether the pain education programme

improved patient satisfaction with nurses and physicians.

The GEE analysis compensated for the baseline heterogeneity

(differences existing before the intervention) between the

experimental and control groups and the effects of maturation

(changes in outcome variables resulting from the passage of

time). To control for the effect of pain intensity on patient

satisfaction, this study factored the mean pain intensity (worst

pain + average pain + least pain + painnow/4) intothe analytic

model. As hypothesised in this study, patients in the experi-

mental group displayed a greater degree of satisfaction regard-

ing pain management. The patients satisfaction with regard to

pain management was a signicant mediator between barriers

to using analgesics and analgesic adherence. The Sobel test

described by Baron and Kenny (1986) and Preacher and Hayes

(2004) was used to examine the mediating effects of variables.

In this manner, we were able to estimate the direct, indirect and

total effects of the causal relationships involving this mediating

variable. In this study, the Sobel test under the SAS SAS system

(version 8.2) was used to assess the mediating role of patient

satisfaction on barriers to using analgesics and analgesic

adherence.

Ethical approval

This study obtained approval from the Human Subject

Committee of the hospital. All subjects signed written

informed consent forms.

Results

Demographic information

The participants in this study suffered from various forms of

cancer, including nasopharyngeal (21%), breast (18%), oral

(16%), liver (13%), lung (6%), colorectal (6%) and various

others (20%). In the experimental group, 61% of the

participants were women. The mean age was 55 (SD

1438). The mean years of education were 774 (SD 423).

The mean KPS score was 81 (SD 138). The mean pain

intensity score was 331 (SD 137) before intervention.

Among these participants in the experimental group, the

cancer identied in 77% of the test subjects had metastasised.

In the control group, 60% of the patients were women.

The mean age was 59 (SD 1660). The mean years of

education were 857 (SD 488). The mean KPS score was 85

(SD 114). The mean pain intensity score was 376 (SD 194)

before intervention. Among these participants in the control

group, the cancer identied in 70% of the test subjects had

metastasised. No signicant difference was displayed be-

tween the two groups regarding the prescriptions (ex:

NSAID, codeine/tramadol, morphine, fentanyl, adjuvant

drugs) provided by physicians. No signicant demographic

differences were noted between the two groups, with the

exception of treatment status (i.e. patients who received

chemotherapy or radiotherapy vs. those who received

neither), which reached signicance (p = 002).

Determining whether the pain education programme

improved patient satisfaction with the pain management

provided by nurses

There was no signicant difference at baseline (p = 01065) in

patients satisfaction levels between the two groups. The

control group showed a signicant maturation effect in the

second and fourth weeks (p = 00027 and p = 00073).

However, the elevation slope of the experimental group

was signicantly higher than that of the control group in both

the second (p < 00001) and fourth weeks (p = 00002),

after adjusting for the effects of treatment and mean pain

intensity. Clearly, the pain education programme signicantly

increased patient satisfaction with the nurses. The satisfac-

tion felt by the experimental group regarding the pain

management of nurses increased signicantly from 395

during the pretest to 518 by the fourth week. On the

contrary, the satisfaction felt by the control group was 428

during the pretest and 472 by the fourth week. Although

both groups displayed a signicant elevation in satisfaction

levels from the pretest to the fourth week, only a minimal

increase in patient satisfaction was observed between the

second week and the fourth week (Fig. 2; Table 1).

Determining whether the pain education programme

improved patient satisfaction with pain management

conducted by physicians

The baseline scores of the experimental group were signi-

cantly lower than the control group with regard to satisfac-

tion with the pain management conducted by physicians

P-L Chou and C-C Lin

1862 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 18581869

(p = 00002). The control group showed signicant matura-

tion in the second week (p = 00415). However, the elevation

slope of the experimental group was signicantly greater than

the control group in both the second (p < 00001) and the

fourth weeks (p < 00001) after adjusting for baseline

heterogeneity, the effect of treatment and mean pain inten-

sity. The pain education programme signicantly improved

patient satisfaction with physicians. The satisfaction felt by

the experimental group regarding the pain management of

physicians increased signicantly from 454 during the pretest

to 564 by fourth week. In contrast, the satisfaction felt by the

control group was 511 during the pretest and 545 by the

fourth week. Despite the signicant improvement in satisfac-

tion in both groups between the pretest and the fourth week,

only a slight improvement was observed in patient satisfac-

tion between the second week and the fourth week (Fig. 3;

Table 2).

Determining the mediating role of patient satisfaction

with nurses to barriers in using analgesics and adherence

to the prescribed use of analgesics

One of the objectives of this study was to determine whether

patient satisfaction with nurses was a mediating factor

between barriers to using analgesics and adherence to the

prescribed use of analgesics. The results revealed that in the

experimental group, patient satisfaction with pain manage-

ment was a mediator between barriers to using analgesics and

adherence to the prescribed use of analgesics (p < 00001),

accounting for 4773% of the observed mediation (Table 3).

However, no mediation relationship was observed in the

control group. Figure 4 shows a path analytic model of the

relationships related to patient satisfaction with nurses,

barriers to analgesic use and adherence to the prescribed

use of analgesics.

Determining the mediating role of patient satisfaction

with physicians on barriers to the use of analgesics and

adherence to the prescribed use of analgesics

This study examined patient satisfaction with physicians to

determine whether a mediating relationship existed between

satisfaction and barriers to the use of analgesics and

adherence to the prescribed use of analgesics. The results

showed that in the experimental group, patient satisfaction

with pain management was a mediator between barriers to

using analgesics and adherence to the prescribed use of

analgesics (p < 00001), accounting for 4556% of the

mediation (Table 3). However, no mediating relationship

Patients satisfaction with nurses (n = 61)

1

2

3

1

2 3

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Test time

S

c

o

r

e

Experimental group

Control group

Experimental

395 507 518

Control

428 47 472

1 2 3

Figure 2 Patients satisfaction score with nurses of Experimental

Group and Control Group (1 = pretest, 2 = second week, 3 = fourth

week). Note: Score was estimated with a generalised estimating

equations model of the patient satisfaction with nurses.

Table 1 Generalised estimating equations model of the patient satisfaction with nurses (n = 61)

Variable

Regression

coefcient

Standard

deviation Z p

Intercept 42817 02391 1791 <00001

Experimental vs. control group 02321 01438 161 01065

Second week vs. pretest 04204 01401 300 00027*

Fourth week vs. pretest 04358 01624 268 00073*

Interaction between second week and group 06991 01561 448 <0001*

Interaction between fourth week and group 07895 02134 370 00002*

Treatment status (yes vs. no) 02535 01539 165 00995

Mean pain intensity (worst pain + average pain + least pain + pain now/4) 00646 00421 153 01248

Interaction between second week and group shows the difference between the experimental and control groups in change between pretest and

second week. Interaction between fourth week and group shows the difference between experimental and control groups in change from pretest

to fourth week. The change in the experimental group is represented by the change in the control group plus the interaction term.

*p < 005.

Pain management Pain education to improve pain management

2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 18581869 1863

was evident in the control group. Figure 5 displays a path

analytic model of the relationships between patient satisfac-

tion with physicians, barriers to analgesic use and adherence

to the prescribed use of analgesics.

Discussion

Very few studies have examined the effectiveness of inter-

vention on patient satisfaction with pain management. Even

fewer studies have shown signicant improvements in patient

satisfaction with pain management, despite implementing

educational interventions. One long-term study (de Wit et al.

1997) conducted in the Netherlands in 1997 focused on 313

homecare patients with cancer. During hospitalisation, health

care professionals conducted face-to-face pain education

followed by a telephone-delivered reiteration of pain educa-

tion on the third and seventh days following discharge. The

researchers found no signicant improvement in satisfaction

with pain control, despite a reduction in pain intensity (de

Wit et al. 1997). Yates et al. (2004) conducted a pain

education programme with 189 homecare patients with

cancer. During the return visit, the health care professionals

administered a pain education session with the patients and

conducted a telephone interview one week after the visit.

Although the programme enhanced the perception of control

in the minds of patients, no signicant difference in patient

satisfaction with pain management was observed between the

rst week and second month following the intervention

(Yates et al. 2004). This may be attributed to the fact that the

interviews on pain education were conducted over the

telephone without face-to-face contact between patients and

medical staff. In addition, the education did not involve any

family members. In this study, however, pain education

consisted of an extended, face-to-face intervention involving

patients and family caregivers.

Previous studies have revealed that the level of patient

satisfaction with pain control might be inuenced by multiple

factors. Sherwood identied three factors inuencing the

patients satisfaction feel regarding pain management. These

factors included previous experience with pain (affecting

beliefs and attitudes regarding pain management and expec-

tations about pain); patient appraisals of health care profes-

sionals (if the health care professionals managed pain with

empathy, care, sufcient knowledge and technique); and

personal experience managing pain (such as the involvement

of family caregivers in the treatment plan and the develop-

ment of effective strategies to cope with pain) (Sherwood

et al. 2000). Studies have also investigated the satisfaction

felt by patients with terminal cancer regarding pain manage-

ment using phenomenology. These studies revealed three

1

2

3

1

2

3

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Test time

S

c

o

r

e

Experimental group

Control group

Experimental

group

454 552 564

Control

group

511 541 545

1 2 3

Patients satisfaction physicians (n = 61)

Figure 3 Patient satisfaction with physicians in the Experimental and

Control Groups (1 = pretest, 2 = second week, 3 = fourth week).

Score was estimated by generalised estimating equations model of

patient satisfaction with physicians.

Table 2 Generalised estimating equations model of patients satisfaction with physicians (n = 61)

Variable

Regression

coefcient

Standard

deviation Z p

Intercept 51124 01894 270 <00001

Experimental vs. control group 05722 01535 373 00002*

Second week vs. pretest 02970 01457 204 00415*

Fourth week vs. pretest 03396 01853 183 00069*

Interaction between second week and group 06812 01579 431 <00001*

Interaction between fourth week and group 07566 01953 387 00001*

Treatment status (yes vs. no) 00359 00875 041 06817

Mean pain intensity (worst pain + average pain + least pain + pain now/4) 01437 00371 387 00001

Interaction between second week and group shows the difference between the experimental and control groups in change between pretest and

second week. Interaction between fourth week and group shows the difference between experimental and control groups in change from pretest

to fourth week. The change in the experimental group is represented by the change in the control group plus the interaction term.

*p < 005.

P-L Chou and C-C Lin

1864 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 18581869

themes inuencing patient satisfaction with pain manage-

ment: communication, planning and trust. Patients expect

health care professionals to communicate in an open and

honest manner regarding pain management. After physi-

cians and nurses gain the trust of patients, patients show an

increased willingness to participate in the pain management

plan (Bostrom et al. 2004). Other factors that may con-

tribute to patient satisfaction with pain management

include a greater degree of social support (Jamison et al.

1993) and the physicianpatient relationship, manifesting

itself as an awareness of empathy and condence in

physicians and nurses (Jamison et al. 1993), such that

patients trust their health care providers (McCracken et al.

1997, Jensen et al. 2004). In addition, a recent study

revealed the four main factors inuencing satisfaction with

the quality of pain management. These included adminis-

tering treatment in a respectful manner, the provision of a

safety net, the efcacy of pain management and the

involvement of the patient as a partner. Among the four

factors, a collaborative relationship between patients and

health care professionals was the most important factor in

pain management determining the degree of control per-

ceived by patients (Beck et al. 2010).

In this study, several factors may explain how providing

pain education contributes to improving patient satisfaction

with pain management. Long-term engagements consisting of

multiple face-to-face visits with systematic pain education

provided patients with the opportunity to discuss how pain

management ought to be implemented. Such discussions

provided the opportunity to describe pain symptoms, evaluate

the effectiveness of medication and discuss the pain manage-

ment plan with physicians and nurses during every clinical

visit. In addition, researchers encouraged patients to take

an active role in their pain treatment and health care

BQT

score

Adherence

049* 085*

Without mediation: 087*

With mediation: 046*

Patient

satisfaction

with nurses

Figure 4 The mediation relationship of patient satisfaction with

nurses on the Barriers Questionnaire-Taiwan form score and anal-

gesic adherence in the experimental group. *p < 005.

BQT

score

Adherence

047* 084*

Without mediation: 087*

With mediation: 047*

Patient

satisfaction

with physicians

Figure 5 The mediation relationship of patient satisfaction with

physicians on the Barriers Questionnaire-Taiwan form score and

analgesic adherence in the experimental group. *p < 005.

Table 3 Sobel test for the mediation effects of patient satisfaction with nurses and physicians on the barriers adherence relationship in the

experimental group

Std b SE p-value

Test of mediation pathway of patient satisfaction with nurses

Barriers (predictor) adherence (outcome) 087 014 <00001

Barriers (predictor) satisfaction (mediator) 049 008 <00001

Satisfaction (mediator) adherence (outcome) 085 016 <00001

Barriers (predictor) adherence (outcome) with mediator 046 015 00028

Mediation results Per cent of the total effect

that is mediated:

4743%

Test statistic: 393 p-value: <00001

Test of mediation pathway of patient satisfaction with physicians

Barriers (predictor) adherence (outcome) 087 014 <00001

Barriers (predictor) satisfaction (mediator) 047 008 <00001

Satisfaction (mediator) adherence (outcome) 084 017 <00001

Barriers (predictor) adherence (outcome) with mediator 047 015 00022

Mediation results Per cent of the total effect

that is mediated:

4556%

Test statistic: 382 p-value: 00001

p-value at 005 level.

Std b, standardised beta coefcient; SE, standard error.

Pain management Pain education to improve pain management

2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 18581869 1865

professionals were expected to keep lines of communication

open regarding the outcomes of pain management interven-

tion. When patients experience care and empathy delivered in

a consistent manner, they perceive their relationship with

health care professionals as collaborative. These factors may

contribute to improving perceptions of pain management.

The factors that inuence adherence are multidimensional.

Several scholars have taken a socio-psychological perspective

in suggesting several factors that inuence patient adherence,

including the physicianpatient relationship, the communi-

cative skills of physicians, the provision of information and

social support (Cameron 1996, Ryan 1999, Lowe et al.

2000). The behaviour and attitudes displayed by health care

professionals can positively or negatively inuence the

adherence of patients (Cameron 1996). One important factor

contributing to the under-treatment of cancer pain is a lack of

adherence to the therapeutic regimen (Lin et al. 2006, Tzeng

et al. 2008, Valeberg et al. 2008). In previous studies, pain

interventions signicantly increased patients knowledge of

pain, but did not improve their adherence to taking analgesics

(Wells et al. 2003, Miaskowski et al. 2004). These results

indicate that merely enhancing patient knowledge with

regard to medication does not signicantly improve adher-

ence to taking prescribed medication. Patient adherence is

inuenced by multidimensional elements, such as socio-

psychological perspectives, which health care professionals

must consider when attempting to break down barriers that

prevent patients with cancer from taking analgesics. Such

considerations could be far more effective than merely

focusing on enhancing patient knowledge. Improving patient

satisfaction with medical care is another way to increase

adherence to prescribed analgesic use, thereby improving the

management of cancer pain.

Results of this study indicate that the implementation of

pain education noticeably increased satisfaction scores dur-

ing the second- and fourth-week follow-ups, compared with

the satisfaction scores in the pretest. Nevertheless, the scores

of the experimental group regarding satisfaction with pain

management provided by nurses signicantly improved from

507 in the second week to 518 by fourth week. In addition,

satisfaction with the pain management provided by physi-

cians increased from 552564 by the fourth week. How-

ever, this incremental improvement was insufcient to

achieve statistical signicance. This study adopted a Likert

six-point scale for the satisfaction questionnaire. Patients

satisfaction felt towards the pain management provided by

nurses was 395 during the pretest, which was between

somewhat unsatised and somewhat satised. In the

second week, the level of satisfaction signicantly increased

to display a score between satised and extremely satised.

On the other hand, patient satisfaction with their physician

was between somewhat satised and satised with a score

of 454 during the pretest, signicantly improving to a point

between satised and extremely satised by the second

week. The above results reveal that patients felt satised to

extremely satised by the second week of pain education.

However, no signicant difference in the change of satisfac-

tion felt by patients was observed during the fourth week.

Because this study only tracked patient satisfaction for four

weeks, no demonstrable change in follow-up satisfaction was

observed. This study suggests several possible explanations

for the lack of signicant changes in satisfaction between the

second and fourth weeks. First, the score regarding the

satisfaction of pain management displayed extremely right-

skewed distribution. Owing to the inuence of ceiling effect,

the margin of improvement was limited. In addition, long-

term follow-up investigation regarding the ongoing commu-

nication between cancer outpatients and physicians revealed

that dimensions such as interest/engagement or friendliness/

warmth were signicantly correlated with the patients

satisfaction felt towards physicians one week or three -

months after outpatient visits. In addition, the correlation

coefcient showed nearly no change, suggesting that there

were no signicant changes in patient satisfaction with

physicians over the short-term or the long-term (Ong et al.

2000). Other studies have also mentioned that testretest

reliability related to satisfaction with physicians was moder-

ately correlated after four weeks (r = 041) (Lam et al. 2005).

Meanwhile, the testretest coefcient regarding patient

satisfaction adopted by the consultation satisfaction ques-

tionnaire was 082 within three weeks (Baker & Whiteld

1992). These studies revealed that patient satisfaction

regarding physicians is relatively stable correlated across

time. Additionally, we must not exclude the degree to which

subsequent interaction with other staff members or patients

cloud these relationships. Because this study only collected

follow-up data for four weeks, we were unable to investigate

long-term changes with regard to satisfaction. Therefore, we

suggest a future study including long-term follow-ups to

gauge changes in the level of patient satisfaction with pain

management.

This study was limited by several factors. First, it was not a

double-blind study. Second, patient satisfaction with physi-

cians or nurses accounted for 45564773% of the mediation

effect on barriers to using analgesics and adherence to the

prescribed use of analgesics. Other factors, such as social

circumstances or medication side effects may have inuenced

these relationships, but remain unexplored. Third, the sample

size used to conduct the Sobel test used to estimate the

mediation effect was small.

P-L Chou and C-C Lin

1866 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 18581869

This is the rst study investigating pain education as a way

to improve the long-term patient satisfaction feel towards

pain management, with an examination of the mediating

effect of patient satisfaction on pain control. This study

found that systematic, face-to-face pain education involving

multiple visits with patients and family caregivers can result

in the long-term enhancement of patient satisfaction with

pain management.

Conclusions

This study veried that patient satisfaction is a mediator with

regard to the barriers to using analgesics and analgesic

adherence. The outcome of the study not only supports the

efcacy of pain education programmes among patients,

family caregivers and medical personnel to improve patient

satisfaction but also emphasises the important role of patient

satisfaction in improving analgesic adherence in patients with

cancer. This change in behaviour could ultimately result in

improvements in the management of cancer pain.

Relevance to clinical practice

Patient satisfaction with physicians and nurses operates

partially as a mediating factor and cannot be discounted

when attempting to improve adherence to the prescribed use

of analgesics. The results of this study show that with respect

to the control of cancer pain, the enhancement of patient

satisfaction can signicantly improve patient adherence. If

physicians and nurses attend only to the delivery of knowl-

edge concerning medication, they may fail to convey to

patients the respect, empathy and active listening patients

need to feel fully satised with their physicians and nurses and

improve patient adherence to the prescribed use of analgesics.

Acknowledgements

The NSC 89-2314-B-083-069 from the National Science

Council in Taiwan funded this study. The authors thank Ms

Denise Dipert for her careful review and for editing this

manuscript.

Contributions

Study design: PLC, CCL; data collection and analysis: PLC

and manuscript preparation: PLC, CCL.

Conict of interest

None declared.

References

Afilalo M & Tselios C (1996) Pain relief

versus patient satisfaction. Annals of

Emergency Medicine 27, 436438.

Agency for Health Care Policy and Research

(1994) Public Health Service. Manage-

ment of Cancer Pain. AHCPR publ. no.

94-0592, AHCPR, Public Health Ser-

vice, U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services, Rockville, MD.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Qual-

ity (2001) Management of Cancer Pain.

AHRQ Publication No. 02-E002.

Agency for Healthcare Research and

Quality, U.S. Department of Health

and Human Services, Rockville, MD.

Baker R & Whitfield M (1992) Measuring

patient satisfaction: a test of construct

validity. Quality in Health Care 1, 104

109.

Baron RM & Kenny DA (1986) The mod-

erator-mediator variable distinction in

social psychological research: concep-

tual, strategic and statistical consider-

ations. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology 51, 11731182.

Beck SL, Towsley GL, Berry PH, Lindau K,

Field RB & Jensen S (2010) Core as-

pects of satisfaction with pain man-

agement: cancer patients perspectives.

Journal of Pain and Symptom Man-

agement 39, 100115.

Bos A, Vosselman N, Hoogstraten J &Prahl-

Andersen B (2005) Patient compliance:

a determinant of patient satisfaction?

The Angle Orthodontist 75, 526531.

Bostrom B, Sandh M, Lundberg D &

Fridlund B (2004) Cancer-related pain

in palliative care: patients perceptions

of pain management. Journal of Ad-

vanced Nursing 45, 410419.

Buccheri G, Ferrigno D & Tamburini M

(1996) Karnofsky and ECOG perfor-

mance status scoring in lung cancer: a

prospective, longitudinal study of

536 patients from a single institution.

European Journal of Cancer 32, 1135

1141.

Cameron C (1996) Patient compliance: rec-

ognition of factors involved and sug-

gestions for promoting compliance with

therapeutic regimens. Journal of

Advanced Nursing 24, 244250.

Chang MC, Chang YC, Chiou JF, Tsou TS

& Lin CC (2002) Overcoming patient-

related barriers to cancer pain man-

agement for home care patients: a pilot

study. Cancer Nursing 25, 470476.

Ferrell BR, Rhiner M & Ferrell BA (1993)

Development and implementation of a

pain education program. Cancer 72,

34263432.

Gordon DB, Pellino TA, Miaskowski C,

McNeill JA, Paice JA, Laferriere D &

Bookbinder M (2002) A 10-year review

of quality improvement monitoring in

pain management: recommendations

for standardized outcome measures.

Pain Management Nursing 3, 116130.

Hirsh AT, Atchison JW, Berger JJ, Waxen-

berg LB, Lafayette-Lucey A, Bulcourf

BB & Robinson ME (2005) Patient

satisfaction with treatment for chronic

pain: predictors and relationship to

compliance. The Clinical Journal of

Pain 21, 302310.

Pain management Pain education to improve pain management

2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 18581869 1867

Hsieh FY (1991) SSIZE: a sample size pro-

gram for clinical and epidemiologic

studies. American Statistician 45, 338.

Jain PN, Myatra SN, Kakade AC & Sareen

R (2008) An evaluation of postopera-

tive epidural analgesia in acute pain

service in an Indian cancer hospital (a

preliminary experience of patient satis-

faction survey). Acute Pain 10, 914.

Jamison RN, Taft K, OHara JP & Ferrante

FM (1993) Psychosocial and pharma-

cologic predictors of satisfaction with

intravenous patient-controlled analge-

sia. Anesthesia and Analgesia 77, 121

125.

Jensen MP, Mendozac T, Hanna DB, Chen

C & Cleeland CS (2004) The analgesic

effects that underlie patient satisfaction

with treatment. Pain 110, 480487.

Lam WWT, Fielding R, Chow L, Chan M,

Leung GM & Ho EYY (2005) Brief

communication: the Chinese medical

interview satisfaction scale-revised

(C-MISS-R): development and valida-

tion. Quality of Life Research 14,

11871192.

Lebow J (1982) Consumer satisfaction with

mental health treatment. Psychological

Bulletin 91, 244259.

Liang KY & Zeger SL (1986) Longitudinal

data analysis using generalized liner

models. Biometrika 73, 1322.

Lin CC (2000) Applying the American Pain

Societys QA standards to evaluate the

quality of pain management among

surgical, oncology, and hospice in-

patients in Taiwan. Pain 87, 4349.

Lin CC (2001) Congruity of cancer pain

perceptions between Taiwanese patients

and family caregivers: relationship to

patients concerns about reporting pain

andusing analgesics. Journal of Painand

Symptom Management 21, 1826.

Lin CC & Ward SE (1995) Patient-related

barriers to cancer pain management in

Taiwan. Cancer Nursing 18, 1622.

Lin CC, Chou PL, Wu SL, Chang YC & Lai

YL (2006) Long-term effectiveness of a

patient and family pain education

program on overcoming barriers to

management of cancer pain. Pain 122,

271281.

Lowe C, Raynor DK, Purvis J, Farrin A &

Hudson J (2000) Effects of a medicine

review and education programme for

older people in general practice. British

Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 50,

172175.

Max M, Donoven M, Portenoy RK, Clee-

land CS, Ready LB, Carr DB, Edwards

WT, Simmonds MA & Evans WO

(1991) American Pain Society quality

assurance standards for relief of acute

pain and cancer pain. In Proceedings of

the IV th World Congress on Pain

(Bond M, Charlton J & Woolf C eds).

Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 186189.

McCracken LM, Klock PA, Mingay DJ,

Asbury JK & Sinclair DM (1997)

Assessment of satisfaction with treat-

ment for chronic pain. Journal of Pain

and Symptom Management 14, 292

299.

Meakin R & Weinman J (2002) The Med-

ical Interview Satisfaction Scale (MISS-

21) adapted for British general practice.

Family Practice 19, 257263.

Merkouris A, Ifantopoulos J, Lanara V &

Lemonidou C (1999) Patient satisfac-

tion: a key concept for evaluating and

improving nursing services. Journal of

Nursing Management 7, 1928.

Miaskowski C, Nichols R, Broady R & Sy-

nold T (1994) Assessment of patient

satisfaction utilizing the American Pain

Societys quality assurance standards on

acute and cancer pain. Journal of Pain

and Symptom Management 9, 511.

Miaskowski C, Dodd MJ, West C, Paul SM,

Tripathy D, Koo P & Schumacher K

(2001) Lack of adherence with the

analgesic regimen: a significant barrier

to effective cancer pain management.

Journal of Clinical Oncology 19, 4275

4279.

Miaskowski C, Dodd M, West C, Schum-

acher K, Paul SM, Tripathy D & Koo P

(2004) Randomized clinical trial of the

effectiveness of a self-care intervention

to improve cancer pain management.

Journal of Oncology 22, 17131720.

Morisky DE, Green LW & Levine DM

(1986) Concurrent and predictive

validity of a self-reported measure of

medication adherence. Medical Care

24, 6774.

Ong LM, Visser MR, Lammes FB & de

Haes JC (2000) Doctor-Patient com-

munication and cancer patients quality

of life and satisfaction. Patient Educa-

tion and Counseling 41, 145156.

Panteli V & Patistea E (2007) Assessing

patients satisfaction and intensity of

pain as outcomes in the management of

cancer-related pain. European Journal

of Oncology Nursing 11, 424433.

Preacher KJ & Hayes AF (2004) SPSS and

SAS procedures for estimating indirect

effects in simple mediation models.

Behavior Research Methods, Instru-

ments, & Computers 36, 717731.

Rich MW, Gray DB, BeckhamV, Wittenberg

C & Luther P (1996) Effect of a multi-

disciplinary intervention on medication

compliance in elderly patients with

congestive heart failure. The American

Journal of Medicine 101, 270276.

Ryan AA (1999) Medication compliance

and older people: a review of the liter-

ature. International Journal of Nursing

Studies 36, 153162.

Rybacki JJ (2002) Improving cardiovascular

health in postmenopausal women by

addressing medication adherence issues.

Journal of the American Pharmaceuti-

cal Association 42, 6371.

Sherwood G, Adams-McNeill J, Starck PL,

Nieto B & Thompson CJ (2000)

Qualitative assessment of hospitalized

patients satisfaction with pain man-

agement. Research in Nursing &

Health 23, 486495.

Simons LE, Logan DE, Chastain L & Ce-

rullo M (2010) Engagement in multi-

disciplinary interventions for pediatric

chronic pain: parental expectations,

barriers and child outcomes. The Clin-

ical Journal of Pain 26, 291299.

Simpson SH, Johnson JA, Farris KB &

Tsuyuki RT (2002) Development and

validation of a survey to assess barriers

to drug use in patients with chronic

heart failure. Pharmacotherapy 22,

11631172.

Sterman E, Gauker S & Krieger J (2003)

Continuing education: a comprehensive

approach to improving cancer pain

management and patient satisfaction.

Oncology Nursing Forum 30, 857864.

Syrjala KL, Abrams JR, Polissar NL, Hans-

berry J, Robison J, DuPen S, Stillman

M, Fredrickson M, Rivkin S, Feldman

E, Gralow J, Rieke JW, Raish RJ, Lee

DJ, Cleeland CS & DuPen A (2008)

Patient training in cancer pain man-

agement using integrated print and vi-

deo materials: a multisite randomized

controlled trial. Pain 135, 175186.

Tsai PS, Chen PL, Lai YL, Lee MB & Lin

CC (2007) Effects of electromyography

biofeedback-assisted relaxation on pain

in patients with advanced cancer in a

palliative care unit. Cancer Nursing 30,

347353.

P-L Chou and C-C Lin

1868 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 18581869

Tzeng JI, Chang CC, Chang HJ & Lin CC

(2008) Assessing analgesic regimen

adherence with the Morisky Medica-

tion Adherence Measure for Taiwanese

patients with cancer pain. Journal of

Pain and Symptom Management 36,

157166.

Valeberg B, Miaskowski C, Hanestad B,

Bjordal K, Moum T & Rustoen T

(2008) Prevalence rates for and predic-

tors of self-reported adherence of

oncology outpatients with analgesic

medications. The Clinical Journal of

Pain 24, 627636.

Wang XS, Mendoza TR, Gao SZ & Clee-

land CS (1996) The Chinese version of

the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI-C): its

development and use in a study of

cancer pain. Pain 67, 407416.

Ward SE & Gordon D (1994) Application

of the American Pain Society qual-

ity assurance standards. Pain 56, 299

306.

Ward SE, Goldberg N, Miller-McCauley V,

Mueller C, Nolan A, Pawlik-Plank D,

Robbins A, Stormoen D & Weissman

DE (1993) Patient-related barriers to

management of cancer pain. Pain 52,

319324.

Ward S, Donova M & Max MB (1998) A

survey of the nature and perceived

impact of quality improvement activi-

ties in pain management. Journal of

Pain and Symptom Management 15,

365373.

Wells N, Hepworth JT, Murphy BA, Wujcik

D & Johnson R (2003) Improving

cancer pain management through pa-

tient and family education. Journal of

Pain and Symptom Management 25,

344356.

de Wit R, van Dam F, Zandbelt L, van

Buuren A, van der Heijden K, Leenh-

outs G & Loonstra S (1997) A pain

education program for chronic cancer

pain patients: follow up results a ran-

domized controlled trial. Pain 73, 55

69.

de Wit R, van Dam F, Loonstra S, Zandbelt

L, van Buuren A, van der Heijden K,

Leenhouts G & Huijer Abu-Saad H

(2001) The Amsterdam Pain Manage-

ment Index compared to eight fre-

quently used outcome measures to

evaluate the adequacy of pain treatment

in cancer patients with chronic pain.

Pain 91, 339349.

Yates P, Edwards H, Nash R, Aranda S,

Purdie D, Najman J, Skerman H &

Walsh A (2004) A randomized con-

trolled trial of a nurse-administered

educational intervention for improving

cancer pain management in ambulatory

settings. Patient Education and Coun-

seling 53, 227237.

Zeger SL & Liang KY (1992) An overview

of methods for the analysis of longitu-

dinal data. Statistics in Medicine 11,

18251830.

The Journal of Clinical Nursing (JCN) is an international, peer reviewed journal that aims to promote a high standard of

clinically related scholarship which supports the practice and discipline of nursing.

For further information and full author guidelines, please visit JCN on the Wiley Online Library website: http://

wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/jocn

Reasons to submit your paper to JCN:

High-impact forum: one of the worlds most cited nursing journals and with an impact factor of 1194 ranked 16 of 70

within Thomson Reuters Journal Citation Report (Social Science Nursing) in 2009.

One of the most read nursing journals in the world: over 1 million articles downloaded online per year and accessible in over

7000 libraries worldwide (including over 4000 in developing countries with free or low cost access).

Fast and easy online submission: online submission at http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/jcnur.

Early View: rapid online publication (with doi for referencing) for accepted articles in nal form, and fully citable.

Positive publishing experience: rapid double-blind peer review with constructive feedback.

Online Open: the option to make your article freely and openly accessible to non-subscribers upon publication in Wiley

Online Library, as well as the option to deposit the article in your preferred archive.

Pain management Pain education to improve pain management

2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 18581869 1869

This document is a scanned copy of a printed document. No warranty is given about the accuracy of the copy.

Users should refer to the original published version of the material.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Effects of Market Orientation On Business Performance - Vodafone Ghana PDFDocument102 pagesThe Effects of Market Orientation On Business Performance - Vodafone Ghana PDFhortalemos100% (1)

- Recommendation From Jamie NordhagenDocument1 pageRecommendation From Jamie Nordhagenapi-244230664No ratings yet

- PPPPC Meeting Minutes 071614Document5 pagesPPPPC Meeting Minutes 071614api-244230664No ratings yet

- Recommendation From Renee AbdellaDocument2 pagesRecommendation From Renee Abdellaapi-244230664No ratings yet

- Signed Final Evaluation 2014Document3 pagesSigned Final Evaluation 2014api-244230664No ratings yet

- Thank You Patient 1Document2 pagesThank You Patient 1api-244230664No ratings yet

- Ce Record 2014 Aurora Davis v2Document1 pageCe Record 2014 Aurora Davis v2api-244230664No ratings yet

- Kudos Email 10 11 13Document1 pageKudos Email 10 11 13api-244230664No ratings yet

- Kudos Email 8 25 13Document2 pagesKudos Email 8 25 13api-244230664No ratings yet

- Thank You New Grad 1Document2 pagesThank You New Grad 1api-244230664No ratings yet

- Focuspdca 7 26 14Document2 pagesFocuspdca 7 26 14api-244230664No ratings yet

- Advisor Checklist CompletedDocument7 pagesAdvisor Checklist Completedapi-244230664No ratings yet

- Kudos Email 8 2 14Document1 pageKudos Email 8 2 14api-244230664No ratings yet

- Kudos Email 3 29 14Document1 pageKudos Email 3 29 14api-244230664No ratings yet

- Preceptor Council AttendanceDocument2 pagesPreceptor Council Attendanceapi-244230664No ratings yet

- Lo6 FeedbackDocument2 pagesLo6 Feedbackapi-244230664No ratings yet

- Preceptor Council AttendanceDocument2 pagesPreceptor Council Attendanceapi-244230664No ratings yet

- Hcahps BMT Data BeforeDocument1 pageHcahps BMT Data Beforeapi-244230664No ratings yet

- Kudos Email 1 13 14Document1 pageKudos Email 1 13 14api-244230664No ratings yet

- Pain Severity Satisfaction With Pain ManagementDocument10 pagesPain Severity Satisfaction With Pain Managementapi-244230664No ratings yet

- January Staff Meeting MinutesDocument3 pagesJanuary Staff Meeting Minutesapi-244230664No ratings yet

- PSC Meeting Agenda 4 2014Document1 pagePSC Meeting Agenda 4 2014api-244230664No ratings yet

- Hcahps Omg Data BeforeDocument1 pageHcahps Omg Data Beforeapi-244230664No ratings yet

- Pain Minutes 031914Document2 pagesPain Minutes 031914api-244230664No ratings yet

- Presentation of Pain Patient Education ToolDocument10 pagesPresentation of Pain Patient Education Toolapi-244230664No ratings yet

- Do Patients Beliefs Act As BarriersDocument13 pagesDo Patients Beliefs Act As Barriersapi-244230664No ratings yet

- Cancer Pain Part 2Document7 pagesCancer Pain Part 2api-244230664No ratings yet

- Cancer Patients Barriers To Pain ManagementDocument12 pagesCancer Patients Barriers To Pain Managementapi-244230664No ratings yet

- Email From Mandy 7 14 14Document1 pageEmail From Mandy 7 14 14api-244230664No ratings yet

- Daisy Nomination Bill ValentineDocument2 pagesDaisy Nomination Bill Valentineapi-244230664No ratings yet

- 1 +Endah+SetyowatiDocument11 pages1 +Endah+Setyowatiebdscholarship2023No ratings yet

- Project Management Framework Through Critical Success Factors For Delivering Power Transmission Construction ProjectDocument24 pagesProject Management Framework Through Critical Success Factors For Delivering Power Transmission Construction ProjectAchintya GhatakNo ratings yet

- SmartPLS UtilitiesDocument11 pagesSmartPLS UtilitiesplsmanNo ratings yet

- Analysis of The Influence of Company Size On The Timeliness of Financial Reporting by Mediating Profitability and Leverage in Companies Listed On The Indonesian Stock ExchangeDocument7 pagesAnalysis of The Influence of Company Size On The Timeliness of Financial Reporting by Mediating Profitability and Leverage in Companies Listed On The Indonesian Stock ExchangeInternational Journal of Business Marketing and ManagementNo ratings yet

- Process Anleitung Alle ModelleDocument90 pagesProcess Anleitung Alle Modellenarjirolu gcpNo ratings yet

- The Saving Behavior of Public Vocational High School Students of Business and Management Program in Semarang SitiDocument8 pagesThe Saving Behavior of Public Vocational High School Students of Business and Management Program in Semarang SitiDaniel Lee Eisenberg JacobsNo ratings yet

- 38 30 PBDocument8 pages38 30 PBMahusay Neil DominicNo ratings yet

- Edi Sugiono, Dewi SV. (2019) - Work Stress, Work Discipline and Turnover Intention On Performance Mediated by Job SatisfactionDocument6 pagesEdi Sugiono, Dewi SV. (2019) - Work Stress, Work Discipline and Turnover Intention On Performance Mediated by Job SatisfactionSiapa KamuNo ratings yet

- Morgades Bamba2019 PDFDocument7 pagesMorgades Bamba2019 PDFArif IrpanNo ratings yet

- Conclusion PDFDocument5 pagesConclusion PDFSamatorEdu TeamNo ratings yet

- Effects of Birth Ball Exercise On Pain and Self-Efficacy During Childbirth: A Randomised Controlled Trial in TaiwanDocument18 pagesEffects of Birth Ball Exercise On Pain and Self-Efficacy During Childbirth: A Randomised Controlled Trial in TaiwanRana Yuda StiraNo ratings yet

- Abdullah & Hwei - Acceptance Forgiveness and Gratitude (Jurnal)Document23 pagesAbdullah & Hwei - Acceptance Forgiveness and Gratitude (Jurnal)Siti Rahmah Budi AswadiNo ratings yet

- The Mediation Role of Organization Citizenship Behaviour Between Employee Motivation and Productivity: Analysis of Pharmaceutical Industries in KRGDocument13 pagesThe Mediation Role of Organization Citizenship Behaviour Between Employee Motivation and Productivity: Analysis of Pharmaceutical Industries in KRGMonika GuptaNo ratings yet

- SPSS and SAS Procedures For Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation ModelsDocument26 pagesSPSS and SAS Procedures For Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation ModelsUff NadirNo ratings yet

- Data Analysis TechniquesDocument16 pagesData Analysis TechniquesAltaf KhanNo ratings yet

- Determinant Analysis of Employee Performance and Organizational Commitment As An Intervening Variable in Building A Clean Serving Bureaucracy AreaDocument12 pagesDeterminant Analysis of Employee Performance and Organizational Commitment As An Intervening Variable in Building A Clean Serving Bureaucracy AreaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- The Role of Management and Trade Union Leadership On Dual Commitment: The Mediating Effect of The Workplace Relations ClimateDocument18 pagesThe Role of Management and Trade Union Leadership On Dual Commitment: The Mediating Effect of The Workplace Relations ClimateSK KHURANSAINo ratings yet

- Testing Mediation Using Medsem' Package in StataDocument17 pagesTesting Mediation Using Medsem' Package in StataAftab Tabasam0% (1)

- Measuring The Critical Effect of Marketing Mix On Customer Loyalty Through Customer Satisfaction in Food and Beverage Products PDFDocument12 pagesMeasuring The Critical Effect of Marketing Mix On Customer Loyalty Through Customer Satisfaction in Food and Beverage Products PDFINTESSO N.V.No ratings yet

- Irawan Et Al (2019) (Perilaku Organisasi)Document16 pagesIrawan Et Al (2019) (Perilaku Organisasi)Dinda PotabugaNo ratings yet

- Statistical Mediation Analysis Using Sobel Test and Process MacroDocument20 pagesStatistical Mediation Analysis Using Sobel Test and Process MacroxxproangelxxNo ratings yet

- The Mediation Role of Change Management in Employee DevelopmentDocument14 pagesThe Mediation Role of Change Management in Employee DevelopmentIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- 4 - The Influence of Social Media Promotion Strategies On Price Mediated Purchase Decisions (Case Study at PT. Lazada Bandung)Document8 pages4 - The Influence of Social Media Promotion Strategies On Price Mediated Purchase Decisions (Case Study at PT. Lazada Bandung)Haren Servis PrinterNo ratings yet

- Jurnal InternasionalDocument9 pagesJurnal InternasionalDwi Nur Cahyani AgustinNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Product Quality and Service Quality On Customer Loyalty Mediated by Customer Satisfaction (Evidence On Kharisma Store in Belu District, East Nusa Tenggara Province)Document14 pagesThe Effect of Product Quality and Service Quality On Customer Loyalty Mediated by Customer Satisfaction (Evidence On Kharisma Store in Belu District, East Nusa Tenggara Province)yuskaraNo ratings yet

- EN The Impact of Marketing Mix Towards Cust PDFDocument9 pagesEN The Impact of Marketing Mix Towards Cust PDFZe ArtNo ratings yet

- Enfermeras Taiwan Con Litwin y StringerDocument10 pagesEnfermeras Taiwan Con Litwin y StringerSebastián Andres Peña RojoNo ratings yet

- Mediation Analysis of Organizational Justice and Job SatisfactionDocument33 pagesMediation Analysis of Organizational Justice and Job SatisfactionAsif Khan NiaziNo ratings yet

- The Cross-Level Mediating Effect of PsychologicalDocument16 pagesThe Cross-Level Mediating Effect of PsychologicalFabián Henríquez CarocaNo ratings yet