Professional Documents

Culture Documents

J J Shirley The Culture of Officialdom An Examination of The Acquisition of Offices During The Mid 18th Dynasty Baltimore 2005

Uploaded by

Jonathan OwensOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

J J Shirley The Culture of Officialdom An Examination of The Acquisition of Offices During The Mid 18th Dynasty Baltimore 2005

Uploaded by

Jonathan OwensCopyright:

Available Formats

The Culture of Officialdom

An examination of the acquisition of offices during the mid-18

th

Dynasty

By

JJ Shirley

A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the

requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy

Baltimore, Maryland

March, 2005

2005 by JJ Shirley

UMI # 3172694

ii

Abstract

Stemming from Helcks Zur Verwaltung des Mittleren und euen Reichs and Der

Einfluss der Militrfhrer, studies on the configuration and development of the

administration of ancient Egypt have focused primarily on discussing the offices and the

duties attached to them, and only secondarily on the office-holders as they relate to their

positions. The current work examines the structure of ancient Egypts government

through a prosopographical and historical investigation of the officials themselves in

order to ascertain how they obtained their positions during the transition from the reign of

Thutmosis III to that of his son Amenhotep II, c.1450-1400 B.C.

The methodology employed reintegrates the titular, genealogical and biographical

information that was available for the officials with the historical context in which they

functioned. Issues relating to how and why these officials became visible are also

considered in order to gain a better understanding of the culture of officialdom. Three

questions are posed; 1) What were the means by which an ancient Egyptian could attain

office?; 2) What does this tell us about the underlying structure of the government during

the mid-18

th

Dynasty?; 3) What do these patterns (or lack thereof) indicate about an

officials or familys influence vis--vis the king in achieving and retaining a position?

The results of the current work demonstrate that the administrative structure

described by Helck, and essentially followed since, should be reevaluated. It now appears

that officials were able to obtain their positions in a variety of ways throughout the period

studied. Direct inheritance and familial nepotism were more prevalent during the reign of

Thutmosis III, while under Amenhotep II the families of his nurses and tutors benefited

iii

from the close relationship formed between the young prince and his caretakers.

Meritorious rise was also a possibility and did not require external circumstances, such as

wartime activity, to instigate it. While the particular men who made up the highest levels

of the administration changed, the elite status of their families did not. This indicates that

the underlying structure of the government was extremely fluid and that while at the

surface the alterations may appear dramatic, in fact they were not.

iv

Dedication

In 1988 I went to Egypt for the first time and fell in love with it the country, the people,

but especially the monuments. A few years later I began my professional academic

career as a student of Egyptian art, archaeology, history and language. This work is the

culmination of that process. It is dedicated to all the people who made my journeys,

adventures, and research possible.

But especially to those who ensured that I finished.

v

Acknowledgements

As is inevitably the case with a project that spans several years, there are a

number of people who have contributed in small and significant ways to the final

product. The project would not have begun without the advice and support of Dr. Betsy

Bryan, and the Department of Near Eastern Studies at The Johns Hopkins University.

Permission to work in Egypt was granted by the Supreme Council of Antiquities and its

directors, previously Prof. Dr. Gaballa Ali Gaballa, and currently Dr. Zahi Hawass. The

fieldwork was undertaken with financial backing from The Johns Hopkins University, an

Exploration and Field Research Grant from the Washington, D.C.-based Explorers Club,

and a USBECA Fellowship funded through The American Research Center in Egypt.

While working in Egypt, The American Research Center in Egypt provided

assistance that I am very grateful for. Special thanks go to Mme. Amira Khattab and Mr.

Amir Abdel Hamid. At the Cairo Museum, I am indebted to Mr. Adel Mahmoud. Salima

Ikram and Nicholas Warner ensured that my time in Cairo was always exciting. In Luxor,

Dr. Yehyia el-Misry, Dr. Mohammed el-Bialy, Mr. Nur Abd el-Gafar, my inspectors, Mr.

Ramadan Ahmed Ali and Mr. Mugi Mahmoud Selim, and the Necropolis guards were all

essential for the daily operations of my work. I could not have recorded some of the

tombs without the help of Chicago House. I would like to especially thank the Director,

Ray Johnson for the loan of ladders, as well as tea and dinners, Will Schenk and Emily

Napolitano for their epigraphic help and enthusiastic company, Yarko Kobylecky, Sue

Lezon, and Ellie Smith for their photographic assistance and Tina Di Cerbo for the loan

of her digital camera, as well as many fun afternoons. I cannot thank Deanna Kiser

enough for her company and coffee during the many months we both worked in Luxor.

vi

Many Egyptologists and Institutes generously shared their work with me. I would

especially like to mention Roland Tefnin, Luc Gabolde, Nigel Strudwick, and Peter

Piccione, all of whom allowed me to examine the tombs they are currently publishing. In

addition, Dimitri Laboury shared his own research on the viziers, while Annie Gasse and

Vincent Rondot allowed me to use their as yet unpublished work on the graffiti at Sehel.

At the Griffith Institute, I would like to thank Jaromir Malek and Elizabeth Miles for

granting me access to, and assistance with, the collection, and John Baines for facilitating

my stay in Oxford. My work at the Egypt Exploration Society in London was

accomplished with the help of Patricia Spencer and Chris Naunton, as well as a

wonderful phone conversation with T.G.H. James.

During the writing process I received constant advice, support, critiques, and

encouragement from both Betsy Bryan and Richard Jasnow. My colleagues and friends in

Baltimore and elsewhere were an important source of sanity while dissertating, and I

would like to especially mention Violaine Chauvet, Ronald Koder, Nicholas Picardo, and

Matthew D. Adams, as well as Susanna Garfein and Ross Garfinkel and their inn. The

last few months in Michigan were greatly helped along with the support of Janet

Richards. Finally, I must thank my dissertation committee, Matthew Roller, Betsy Bryan,

Richard Jasnow, Raymond Westbrook, and David OConnor for their participation and

valuable comments.

The support of my family has been constant from the very beginning, and I owe

them all a special thanks, but especially my mom and dad for always encouraging me to

pursue my dreams. A final thank you goes to Diane Kagoyire, for getting me back on

track, and to Raphael Cunniff, for keeping me there.

vii

Table of Contents

Title Page i

Abstract ii

Dedication iv

Acknowledgments v

Table of Contents vii

List of Figures xii

Abbreviations xv

Introduction: Attaining Office in the Time of 1-58

Thutmosis III and Amenhotep II

I. Purpose of Research 1

II. Historical Background 3

III. Prosopographical Studies 14

IV. Methodology 23

V. Data Analysis 27

VI. Structuring of the data 33-55

VIa. Appointment 34

VIb. Heredity 45

VIc. Nepotism 46

VId. Merit 52

VII. Data presentation 54

viii

Chapter 1 59-176

The Power of Heredity: Inheritance and Influence

I. Introduction 59-75

Ia. Lineage 60

Ib. Staff of Old Age (mdw iAw) 64

Ic. The imyt-pr, adoption, and other legal methods 69

of ensuring succession

Id. Appointment and Heredity 73

Ie. Conclusion 74

II. Officials 75-163

Ahmose-Aametu, his son User-amun and grandson Rekhmire 75

(Three generations of viziers)

Aametus extended family and later generations 95

(Involvement in the Amun priesthood)

Amenemhat (scribe and steward of the vizier) 101

Menkheperresoneb and his nephew Menkheperresoneb 110

(Two generations of high priests of Amun)

Minnakht and his son Menkheper(resoneb) 122

(Two generations of overseer of granaries)

Amunemhat, son of Itnefer 138

(mid-level priests)

Amenemhat 145

(A new high priest of Amun)

Min and his son Sobekhotep 152

(Two generations of treasurers; Three generations of mayor through marriage)

Excursus: A possible tomb for Min in Thebes 157

Userhat 160

(Two generations of Amun servants)

ix

III. Conclusions 163

Chapter 2 177-329

Influence as a Means of Obtaining Office: The Family and The King

I. Introduction 177

II. Family Influence 181-282

IIa. Familial Nepotism 181-199

The Family of Qen 181

(Karnak clergy and staff)

Amunhotep and his uncle Neferhotep 185

(Priests in the royal mortuary temples)

Baki and his father Bak[enamun] 190

(Mid-level priests)

Ahmose and his son Ra 193

(Priests at Karnak and in the royal mortuary temples)

IIb. The Family and the King 200-282

Taiunet and her son Menkheperresoneb 200

(A royal nurse and her son the high priest of Amun)

Iamnefer and his son Suemniut 205

(A regional mayor and tutor and his son the royal butler)

Usersatet, viceroy of Kush 216

(A man of elite origins)

The Family of the Mayor of Thebes Sennefer 240-259

A. The Parentage of Sennefer 240

B. Ahmose-Humay, his son Amenemopet (called Pairy) 246

and his nephew Sennefer

(A tutor, his son the vizier, and nephew the mayor of Thebes)

Hunay and her son Mery 259

(A royal nurse and her son the high priest of Amun)

Amenemipet and her son Qenamun 265

(A royal nurse and her son the steward of the king and steward of Perunefer)

x

III. Personal Influence 282-313

Nebamun and his son Paser 282

(Friendship with the king is more important than family)

Amenmose 290

(From the field to the court)

Montuiywy 297

(Royal butler and court follower)

Pehsukher 305

(A court-based military official)

IV. Conclusions 312

Chapter 3 331-431

Meritorious Rise to Office

I. Introduction 331

II. Officials 333-432

Sennefri 333

(His rise from a Sna in the Delta to overseer of the seal)

Iamunedjeh 351

(A controller of works abroad and in Egypt)

Userhat 367

(From idnw of the royal herald to Xrd n kAp of Amenhotep II)

Amenemheb-Mahu and Baky 380

(A career military man and his royal nurse wife)

Minmose 401

(An idnw for the king abroad and overseer of works in Egypt)

Dedy 418

(From soldier to royal messenger to chief of the Medjay)

Tjanuny 424

(From army scribe to overseer of the army of the king)

xi

III. Conclusions 432

Conclusions 444-457

Changing Continuity in the Movement of Office

Figures 458-510

Works Cited 511-544

xii

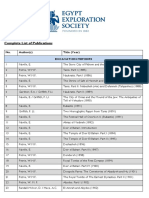

List of Figures

Fig. 1 Table of ancient Egyptian kinship terminology 458-59

with anthropological equivalents

Fig. 2 Genealogy of Aametu, indicating the line of viziers 460

and marriage into the priestly family of Ineni

Fig. 3 Gebel es-Silsilah Shrine 17 (after Caminos) 461

Fig. 4 Co-Installation Scene of User (after Dziobek) 462

Fig. 5 Co-Installation Text of User (after Dziobek) 463

Figs. 6-7 Rekhmires Family wall (after Davies) 464-5

Fig.8 Extended genealogy of Aametus family, indicating 466

their positions throughout the Amun priesthood

Fig.9 Genealogy of Amenemhat (after Davies) 467

Fig.10 Amenemhats Family wall (after Davies) 468

Fig.11 Menkheperresoneb (i)s Family 469

Fig. 12 Minnakht and Menkheper(resoneb) (after Guksch) 470

Figs. 13-15 Amenemhat (TT53) stele lunette 471-3

Figs. 16-18 TT143 474-6

Fig. 19 Qens family 477

Fig. 20 Amunhotep offers to his parents (rt.) 478

Amunhotep offers to his parents (left)

Fig.21 Baky offers to his parents 479

Fig. 22 Usersatet Semna stele (after der Manuelian) 480

Fig. 23 Usersatet Ras Sehel graffito (after Habachi) 481

Fig. 24a-b Gebel es-Silsilah Shrine 11 (after Caminos) 482

xiii

Fig. 25a-b Gebel es-Silsilah Shrine 11 (after Caminos) 483

Fig. 26 Ahmose-Humay, TT224, passage 484

Fig. 27 TT224 faade 485

Fig. 28 Qenamuns father, TT93 486

Fig. 29 Qenamuns mothers name, TT93 487

Fig. 30 Pehsukher in Qenamuns tomb (after Davies) 488

Qenamuns mother and the king

Fig. 31 Paser before Amunhotep II 489

Fig. 32 Amenmose in Syria (Authors photo) 490

Fig.33 Kings in Montuiywys tomb 491

Fig.34 Pehsukher and Neith before Amunhotep II 492

Fig. 35 Sennefri in Lebanon (after Strudwick) 493

Fig. 36 Iamunedjehs stele 494

Fig. 37 Marseille stele 495

Fig. 38 Iamunedjeh in TT56 of Userhat 496

Figs. 39-40 Userhat before Amenhotep II (after Beinlich-Seeber) 497-8

Fig. 41 Amenemheb-Mahu autobiography 499

Fig. 42 Baky offers to Amenhotep II 500

Fig. 43 Mahu and Baky with Amunhotep II 501

Fig. 44 Mahus garden estate 502

Fig. 45 Baky suckles young Amenhotep II 503

Fig. 46 Inscription of Baky owning a tomb 504

Fig. 47 Minmose statue BM2300 505

xiv

Fig. 48 Dedys funerary cones (after Davies & Macadam) 506

Fig. 49 Kings in Dedys tomb 507

Fig. 50 Radwan sketch of above scene 508

Figs. 51-2 Tjanuny records troops 509-10

xv

Abbreviations

A gyptologische Abhandlungen

AT gypten und Altes Testament

ACE Studies Australian Centre for Egyptology Studies

AEL Ancient Egyptian Literature

AEO Ancient Egyptian Onomastica

F gyptologische Forschungen

AL Anne Lexicographique. gypte Ancienne

AE Law A History of Ancient ear Eastern Law

ARCE American Research Center in Egypt

ASAE Annales du Service des Antiquits de l'gypte

ASE Archaeological Survey of Egypt

AV Archologische Verffentlichungen

BACE The Bulletin of the Australian Centre for Egyptology

BAR J.H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt

BASOR Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research

BdE Bulletin de l'Institut d'gypte

BES Bulletin of the Egyptological Seminar

Beitrge Bf Beitrge zur gyptischen Bauforschung und Altertumskunde

BIFAO Bulletin de l'Institut Franais d'Archologie Orientale du Caire

Bijdragen Tot Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land-, en Volkenkunde

BiOr Bibliotheca orientalis

xvi

BMMA The Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

BMRAH Bulletin des Muses Royaux d'Art et d'Histoire

BSFE Bulletin de la Socit Franaise d'gyptologie

CAA Corpus Antiquitatum Aegyptiacarum

CAH Cambridge Ancient History

CAE Civilizations of the Ancient ear East

CASAE Cahier, Supplment aux Annales du Service des Antiquits de

l'gypte

CdE Chronique d'gypte

Cnes Funraires G. Daressy,Recueil des cnes funraires, in: MMAF 8, Part 2

CRS Centre de Recherches d'Histoire Ancienne

CWS Centre of on-Western Studies

Corpus N. de G. Davies and M.F. Laming Macadam, Corpus of Inscribed

Egyptian Funerary Cones

CRIPEL Cahiers de Recherches de l'Institut de Papyrologie et

d'gyptologie de Lille

DE Discussions in Egyptology

EAZ Ethnographisch-archologische Zeitschrift

EEF Egypt Exploration Fund

EES Egypt Exploration Society

FIFAO Fouilles de l'Institut Franais d'Archologie Orientale du Caire

GM Gttinger Miszellen

HS Hamburger gyptologische Studien

HB Hildesheimer gyptologische Beitrge

JAOS Journal of the American Oriental Society

xvii

JARCE Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt

JEA The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology

JEOL Jaarbericht van het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch Gezelschap Ex

JESHO Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient

JES Journal of ear Eastern Studies

JSSEA The Journal of the Society of the Study of Egyptian Antiquities

KRI K. Kitchen, Ramesside Inscriptions

LAAA Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology

Ld Lexikon der gyptologie

LS Leipziger gyptologische Studien

MS Mncher gyptologische Studien

MU Mnchener gyptologische Untersuchungen

MDAIK Mitteilungen des Deutschen Instituts fr gyptische

Altertumskunde in Kairo

MIFAO Mmoires publis par les membres de l'Institut Franais

d'Archologie Orientale du Caire

MMAF Mmoires publis par les membres de la Mission Archologique

Franaise au Caire

MonPiot Fondation Eugne Piot, Monuments et mmoires

MRTO Military Rank, Title and Organization in the Egyptian ew

Kingdom

AWG achrichten von der Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Gttingen

OA Oriens Antiquus

OBO Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis

OED Oxford English Dictionary

xviii

Pd Probleme der gyptologie

PM B. Porter and R. Moss, Topographical Bibliography I.1

PMMA Publications of the metropolitan Museum of Art

PSBA Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology

RdE Revue d'gyptologie

RIDA Revue Internationale des droits de lantiquit

RPTMS Robb de Peyster Tytus Memorial Series

RT Recueil de travaux relatifs la philologie et l'archologie

gyptiennes et assyriennes

SAGA Studien zur Archologische und Geschichte Altgyptens

SAK Studien zur altgyptischen Kultur

SAOC Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization

SBL Writings Writings from the Ancient World, Society of Biblical Literature

SHCAE Studies in the History and Culture of the Ancient ear East

TIP K. Kitchen, Third Intermediate Period

TTS Theban Tomb Series

UGA Untersuchungen zur Geschichte und Altertumskunder gyptens

Urk. IV Urkunden des gyptischen Altertums, Abteilung IV, Heft 17-19

VA Varia Aegyptiaca

WB Wrterbuch der gyptischen Sprache

ZS Zeitschrift fr gyptische Sprache and Altertumskunde

1

Introduction

Attaining Office in the Time of Thutmosis III and Amenhotep II

I. Purpose of the research

The organization of the government

1

in ancient Egypt has long been a topic of

interest among scholars from all branches of the discipline of Egyptology. Discussions on

the structure of Egypts administration

2

have ranged from general historical overviews,

3

to the documentation available for a particular period,

4

or reign.

5

Previous scholars have

also focused on the organization and influence of particular areas of administration within

the overall government,

6

or on the development of a particular office over time.

7

1

In his entry for the Oxford Encyclopedia (Vol.3, pp.314-9) on the ancient Egyptian state, Wilkinson

says The structure of the state may be divided for convenience into three broad areas: the king and

members of the royal family; the government of Egypt; and the government of Egypts foreign

possessions (p.316). The entity which is the government of ancient Egypt is generally further subdivided

into state (or central), provincial, religious and military areas of administration. The term government is

thus used here as an overarching term for the entire (internal) system comprising several different units of

administration. The term administration can, however, encompass both the entire system or can refer to

discrete areas within the government, i.e., religious, civil (central and provincial), royal domain and

military, each of which had their own structure and administrative system. My use of this terminology

essentially follows the interpretation of the structure suggested by OConnor in: Social History, pp.204-18

and schematically outlined in Fig. 3.4. See also the entry by Wilkinson cited above; Quirke, in: Oxford

Encyclopedia Vol.1, pp.12-16; Doxey, in: Oxford Encyclopedia Vol.1, pp.16-20; Haring, in: Oxford

Encyclopedia Vol.1, pp.20-3.

2

See note 1.

3

See, for example, Edgerton, JES 6, pp.152-60; Kemp, in: Garnsey and Whittaker, Imperialism, pp.7-57

and 284-297; Leprohon, in: CAE I, pp.273-87; Trigger, et al., Social History.

4

Especially significant are the studies of Baer, Rank and Title; Helck, Beamtentiteln; Helck, Verwaltung;

Kanawati, Egyptian Administration; Kanawati, Governmental Reforms; Strudwick, Administration; Quirke,

Administration; Quirke, RdE 37, pp.107-30. See also McDowell, Jurisdiction (concerning Deir el-Medina);

Kadry, Officers and Officials. A list of the principal administrative documents, as well as a succinct

discussion of other types of sources that provide information about the administration of ancient Egypt can

be found in Quirke, in: Oxford Encyclopedia Vol.1, pp.23-9. Of the twenty-one sources he mentions, two

date to the Old Kingdom, five to the Middle Kingdom, three to the 18

th

Dynasty, ten to the Ramesside

Period, and one to the Third Intermediate Period.

5

These include Bryan, Thutmose IV; Bryan, in: Thutmosis III, forthcoming; der Manuelian, Amenophis II;

Murnane, in: Amenhotep III; Schmitz, Amenophis I.

6

Examples include Faulkner, JEA 39, pp.32-47; Gnirs, Militr; Hayes, in: CAH II.1,pp.353-72; Helck,

Einfluss; Kees, Priestertum; Kanawati, Akhmim; Leprohon, JAOS 113, pp.434-6; Schulman, MRTO;

Schulman, in: CAE I, pp.289-301.

2

Common to almost all of these studies is that their descriptions of the

configuration and development of the ancient Egyptian government have focused

primarily on discussing the offices themselves and the duties attached to them, and only

secondarily on the office-holders as they relate to the positions they held.

8

As a result,

officials have essentially been turned into symbols of their office(s), which have been

regarded as paramount. In reality however, ancient Egyptian officials were not

synonymous with their positions. Although a title- and function-based study of the

administration can provide a great deal of information about the organizational

components of the government,

9

it is much less able to contribute to our understanding of

how this structure was maintained or changed over time.

10

Another consequence of this

has been that when the officials are in fact discussed, it is only those who are the most

prominent and most visible. While this may be a factor of the available material, it is still

important to ask the question how did these men become visible? That is, why are they

known to us today and how did they attain a level which allows us to know about them?

11

7

New Kingdom studies include those by Bohleke, Double Granaries; Eichler, Verwaltung des Hauses

des Amun; Roehrig, Royal urse; van den Boorn, Duties.

8

The most obvious examples of this are Helcks two main works, Beamtentiteln and Verwaltung, and to a

lesser extent his Einfluss. This method has essentially been followed in more recent works on the Old and

Middle Kingdoms, e.g.., Kanawati, Egyptian Administration; Kanawati, Governmental Reforms;

Strudwick, Administration; Quirke, Administration. It is also noticeable in recent tomb publications of the

Archologische Verffentlichungen and Theben series. See also general studies such as those of Edgerton,

JES 6, pp.152-60; Leprohon, in: CAE I, pp.273-87; and in Trigger, et al. Social History. Research on

specific areas of the government, especially the military administration, also often takes this approach, e.g..,

Chevereau, Prosopographie du ouvel Empire; Faulkner, JEA 39, pp.32-47; Schulman, MRTO.

9

Thus Kemp, in: Social History (p.80), states in reference to the paucity of administrative documents from

the Old Kingdom: In their place we must rely heavily on the very numerous titles born by officials.

Likewise Leprohons conclusion that in the New Kingdom From the general lack of midlevel management

administrative titles, it seems as if the administration itself revolved more than ever around the person of

the king. (in: CAE I, pp.283-4).

10

On this issue see, for example, Cruz-Uribe, in: For His Ka, pp.45-53.

11

Baines and Eyre provide an interesting discussion of this from the point of view of literacy levels in

ancient Egypt; Baines and Eyre, GM 61, pp.65-96, esp. pp.65-77. On the topic of the literacy of women in

3

This study takes a rather different approach to examining the structure of ancient

Egypts government than has previously been applied. What follows is a

prosopographical and historical investigation of the officials themselves in order to

ascertain how officials obtained their positions during the transition from the reign of

Thutmosis III to that of his son Amenhotep II, c.1450-1400 B.C.

12

Three questions are

posed. First, what were the means by which an ancient Egyptian could attain office?

Second, what does this tell us about the underlying structure of the government during

this time period? For example, what positions were available to what types of individuals,

were there restrictions based on family or ones relationship to the court or king? Are

there trends that can be seen for particular areas of the government? Third, what do these

patterns (or lack thereof) indicate about an officials or familys influence vis--vis the

king in achieving and retaining a position? The originality of this dissertation lies in its

fresh, and in some respects less burdened, approach towards understanding the

underlying framework of Egypts administration.

II. Historical Background

The time frame of this examination is limited to the transition between the sole

reign of Thutmosis III and his son Amenhotep II for specific reasons. The first is that a

central tenet of the present work is that the composition of the government can be better

understood by focusing on the officials themselves, rather than on the titles they held. In

order to answer the questions raised above, each official needs to be examined in great

detail, and a circumscribed time period allows for this more than a broad survey of the

the New Kingdom, see Bryan, BES 6, pp. 17-32.

4

entire 18

th

Dynasty. Second, despite the narrow chronological focus, there is an extremely

rich body of data available within the cultural material belonging to the officials

themselves, specifically information found in tomb and shrine inscriptions and

decorations, statues, stelae, funerary cones and equipment, papyri and graffiti.

13

An important part in choosing this particular portion of the mid-18

th

Dynasty is

that this was a historically significant and dynamic period during which changes in

foreign affairs (i.e., ongoing campaigns in the Near East), as well as domestic

developments, appear to have had a considerable impact on the structure of the

government.

14

Thus, this brief review of the historical events leading up to the sole reign

of Thutmosis III will help to situate the current study.

At the end of Second Intermediate Period (c.1650-1550 B.C.), as the Hyksos were

being driven out of Egypt and the country once again became unified under a single

Egyptian king, Ahmose, founder of the 18

th

Dynasty, began the process of re-

organization.

15

On the military front, this involved a series of campaigns into southern

Palestine designed to drive out the remaining Hyksos, assert Egypts newfound strength,

and solidify Egypts borders with the southern Levant. In addition, campaigns were

12

These two kings reigned during the mid-18

th

Dynasty of the New Kingdom.

13

A quick review of Porter and Moss, Topographical Bibliography I.1, and Kampp, Die thebanische

ekropole, as well as the numerous monographs, articles and tomb publication that relate to this period,

clearly demonstrates this.

14

The burgeoning of the military and its influence during the New Kingdom in general has been widely

discussed; cf. Faulkner, JEA 39, pp.32-47; Gnirs, Militr; Helck, Einfluss; Sve-Soderbergh, avy;

Schulman, MRTO; Spalinger, Aspects. Most recently, Redford has re-visited foreign activity in the time of

Thutmosis III, while Spalinger has done the same with the New Kingdom military in general; cf. Redford,

Wars; Spalinger, War. On a variety of domestic developments, religious and civil, see, for example,

Assmann, Egyptian Solar Religion; Boorn, Duties; Dorman, Senenmut; Dziobek, Denkmler; Gitton, Les

Divines pouses; Robins, in: Images and Women, pp.65-78.

15

Vandersleyen is still the primary work on Ahmose; cf. his monograph Amosis, RdE 19, pp.123-59 and

RdE 20, pp.127-34, and also La valle du il ii. Also relevant are Bietak, Avaris; Lacovara, Deir el-Ballas;

Oren, The Hyksos; Smith and Smith, ZS 103, pp.48-76; Wiener and Allen, JES 57/1, pp.1-28. For recent

and succinct reviews of the period, cf. Bourrieau, in: Oxford History, pp.185-217, esp.210-17; Bryan, in:

Oxford History, pp.218-23; Quirke, in: Oxford Encyclopedia Vol.3, pp.260-5.

5

needed in the south in order to regain control of Lower Nubia and its resources, as well as

defeat the Kushite Kingdom which had risen during the Second Intermediate Period.

16

Domestically, Ahmoses concerns centered on establishing a strong dynastic line, re-

asserting royal control over the northern portion of Egypt (north from Cusae), which had

previously been under the rule of the Hyksos, and developing an administrative

organization to run the newly reunited country. Demonstrating devotion to the god

Amun, the chief god of Thebes and now the national deity, was also an important activity

for the Theban-based kings.

17

The prominent role that the royal women played in this early period is well known

and often discussed by scholars.

18

Ahhoteps apparent governance of Egypt and military

activity during her son Ahmoses minority is attested to on his year 18 Karnak stele.

19

The act of marrying ones (half-)sister was a policy begun by Ahmose whose goal was to

consolidate royal power and stabilize the familys control of the dynastic line.

20

The

Donation stele, also erected in Karnak by Ahmose, records the establishment of the office

Gods Wife of Amun (GWA) by Ahmose on behalf of his wife Ahmose-Nefertari. He

bequeaths the office and its associated holdings to Ahmose-Nefertari and her chosen

successors in perpetuity.

21

The GWA performed specific temple rituals as a priestess,

16

On this topic see most recently Morris, Imperialism, esp. pp.27-30, 38f., 41ff., 56ff.; cf. Kemp, in:

Imperialism, pp. 7-57 and 284-297; Redford, Egypt, Canaan and Israel, pp.98-122, 125-55; Weinstein,

BASOR 241, pp.1-10.

17

Bryan, in: Oxford History, p.218ff.

18

Tetishery, grandmother of Ahmose, was honored during his reign, while Ahhotep and Ahmose-Nefertari

were prominent in the reigns of their husbands and sons. See, for example, Bryan, in: Oxford History,

pp.226-30; Eaton-Krauss, Cd 65, pp.195-205; Gitton, Lpouse du dieu; Robins, Wepwawet 2, pp.10-14;

Robins, GM 62, pp. 67-77; Robins, Women, pp.42-52.

19

CGC 34001; cf. Urk. IV, 14-24.

20

Cf. Vandersleyen, Cd 52, pp.234ff.; Bryan, in: Oxford History, pp.226ff.

21

On the Donation stela and the office of Gods Wife in general, see Graefe, Gottesgemahlin; Harari, ASAE

56, pp.139-201; Menu, BIFAO 77, 89-100; and the various works by Gitton: Gitton, Les Divines pouses;

Gitton, Lpouse du dieu; Gitton, BSFE 75, pp.31-46; Gitton and Leclant, in: Ld II, cols. 792-812. See

6

which gave her religious power within the cult. In addition, the land holdings attached to

the position meant significant economic power.

22

By placing this office, which had its

own priesthood, land, and endowments, in the hands of the royal women, Ahmose not

only strengthened the link between the national deity and the royal family, but increased

the latters wealth as well.

23

In addition to strengthening the role of kingship, Ahmose was concerned with the

administration of his newly re-unified country. As van den Boorn has shown, the Duties

of the Vizier was composed sometime during the reign of Ahmose, and hence reflects the

administrative organization that he was attempting to establish.

24

According to van den

Boorn, this was to be a less complex, more direct type of government. His (i.e.,

Ahmoses) aim was apparently to establish a powerful and pervasive royal authority

based on an administration with more efficient, personal and direct ties between its

various echelons to transform it into an efficient and more direct system under a

strong and powerful kingship.

25

Van den Boorn suggests that once Ahhotep died,

Ahmose needed to replace this personal and trustworthy assistant, and that instead of

looking to the royal family he began a policy to seek the support of personal delegates

for the enactment of his reorganizations.

26

The establishment of the position Viceroy of

Kush to oversee the governance of Nubia, and the development of the viziers position

with regard to Egypt proper were the two most important officials for this purpose.

27

also Bryan, in: Mistress of House, pp. 31f.; Robins, Women, pp.44ff., 149-56; Robins, in: Images of

Women, pp.64-78.

22

Robins, in: Images of Women, pp.71, 73.

23

Redford, History and Chronology, pp.70ff.; Robins, in: Images of Women, p.66.

24

Boorn, Duties, pp.333-76; cf. the review by Lorton, Cd 70, pp.123-132.

25

Van den Boorn, Duties, p.349.

26

Van den Boorn, Duties, pp.347f., 355, 359, 370f.

27

Van den Boorn, Duties, p.355.

7

Van den Boorn interprets the Duties as a reflection of Ahmoses refocusing of the

vizierate to become essentially the main civil office supporting royal government,

28

granting the vizier authority as the director of the royal domain, head of the civil

administration and also making him the kings personal delegate.

29

It is the latter role that

the viziers close relationship with the king emerges, since the activities are those where

the vizier serves as a mediator, representative and spokesman on the kings behalf.

30

The

danger in installing too much power on one individual is of course that the individual will

assert his authority to a degree that becomes dangerous to the kings control. Van den

Boorn states that the daily salutation (and information) ceremony of section 3 of the

Duties demonstrates both Ahmoses concern over this possibility and how the king

remained in command of his extremely powerful vizier.

31

Yet this seems to be

contradicted by the fact that during or shortly after the reign of Ahmose, Aametu and his

two successors, User and Rekhmire, were able to form a vizierate dynasty, in a sense

creating the independent centre of power that Ahmose was attempting to prevent.

32

Van den Boorn resolves this by suggesting that the hereditary nature of the vizierate at

this time, as well as its possible family connection to the other major position, viceroy of

Nubia, may have been a planned policy on the part of the king a re-establishment of

the position of the vizierate of the 13

th

dyn. but now in support of a strong

monarchy.

33

28

Van den Boorn, Duties, p.375.

29

These are van den Boorns three main aspects, which he details in Duties, ch.3, pp.309-31.

30

Van den Boorn, Duties, ch.3.2.3, pp.320ff. with fig.11, and p.355f.

31

Van den Boorn, Duties, p.355.

32

The existence of this family of viziers is not new information, but was noted already by Dunham, JEA

15, pp.164-5 and Davies, Rekh-mi-R' I, p.101-2. See also the discussions by Caminos and James, Silsilah

I, pp.42-52, 57-63 and Helck, Verwaltung, pp.285-98, 433-41. This family is re-visited and discussed at

length in Chapter 1, see pp.74-100

33

Van den Boorn, Duties, p.370f. He in fact credits the family of Aametu with four generations of viziers,

8

Moving ahead to the mid-18

th

Dynasty and the events following the death of

Thutmosis II, Dziobek

34

would certainly agree with van den Boorns statement. The exact

length of Thutmosis IIs reign is uncertain, but it was quite likely short, since he died

when his heir, Thutmosis III, was still a young child.

35

The explanation for how

Hatshepsut was able to assume kingship, rather than remain as regent for her nephew and

stepson, is still not completely understood. Hatshepsuts self-legitimization strategy can

be seen in her Birth and Coronation scenes, which were placed on the walls of her

mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri.

36

Her divine birth as the daughter of the god Amun and

Thutmosis Is wife Ahmose, combined a hereditary claim with a divine right to the

throne. Hatshepsuts presentation, acceptance, and coronation before Amun and the gods

of Egypt, as well as Thutmosis I and the royal court demonstrated that she was the chosen

heir.

37

Although these scenes are extremely interesting for what they impart concerning

how Hatshepsut wished her assumption of royal power to be viewed by her subjects, they

tell us very little about how this was actually effected. Indeed, although Hatshepsut

presents herself as the chosen successor of Thutmosis I,

38

it is clear from other

monuments that this was not, in fact the case.

39

The different theories explaining Hatshepsuts accession were outlined by

the first being an unknown ancestor of Aametu; cf. Duties, pp.368ff.

34

I a referring here to his reconstruction of Users involvement in Hatshepsuts accession; cf. Dziobek,

Denkmler.

35

The only known date is for year one, though Thutmosis II is often credited with up to eleven years. On

this subject are several articles by Gabolde, e.g., SAK 14, 61-87; Karnak 9, 1-82.

36

Featured on the north side of the second colonnade in her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri. Cf. Urk. IV,

215-34, 255-58; BAR 2, 187-213, 215-242

37

This in fact draws upon an example set by her father, Thutmosis I, on his stele at Abydos, wherein the

priests of Osiris proclaim him as born of Osiris. Urk. IV, 94-103; BAR 2, 90-8.

38

Cf. the inscriptions found on the upper terrace of Deir el-Bahri, where there were chapels to both

Hatshepsut and Thutmosis I. Urk. IV, 241-74.

39

Murnane, Coregencies, p.116.

9

Dorman in his monograph on Hatshepsuts steward Senenmut.

40

Most scholars viewed

her as some sort of usurper to the throne, based in large part on the assumption that that

Thutmosis III carried out an immediate defacement of Hatshepsuts monuments, either as

an act of retribution,

41

or out of political necessity.

42

Dorman, however, convincingly

demonstrated that the intentional mutilation did not begin until much later in Thutmosis

IIIs sole reign, c. year 46, thus removing the motivation behind the earlier theories.

43

In

addition, inscriptions such as that from the tomb of Ineni (TT81) seem to indicate that her

assumption of power was fairly gradual.

44

Some scholars have suggested that

Hatshepsuts position as GWA was a prominent factor, or perhaps motivator, in her

ability to assume the throne as co-regent / king.

45

The high level of wealth and influence

that this title carried for both Ahmose-Nefertari and Hatshepsut is suggested by their self-

identification as GWA much more often than the various royal designations kings

daughter, king sister, great royal wife, or kings mother.

46

The extent of this

power is especially visible during Hatshepsuts tenure as gods wife

47

and during her

transition from regent to king, when she passes the title to her daughter Neferure and

links the management of the domain with that of the palace and the temple of Amun.

48

40

Dorman, Senenmut, Ch.1, pp.1-17, esp. pp.10-14.

41

For example, Helck, Verwaltung, p.542; Wilson, Burden,pp.175-7; Hayes, in: CAH II.1, pp.318-19.

42

Thus, Redford, History and Chronology, p.87.

43

Dorman, Senenmut, esp. Ch.3, pp.46-65. though I would mention that Bryan, following van Siclen (GM

79, p.53) has suggested that the late date of the defacement and its continuation b Amenhotep II may

indicate that Thutmosis III initiated it in order to ensure Amenhotep IIs succession to the throne; cf. Bryan,

in: Mistress, p.34 with notes 70-2, in: Oxford History, pp.243f., 248, and in: Amenhotep III, p.31 with note

20.

44

Bryan, Mistress, p.32; BAR 2, 341-42; Urk. IV, 59-61.

45

Thus, Redford, in: History and Chronology, Ch.4, pp.73ff.; Robins, in: Images of Women, pp.76ff.

46

Bryan, in: Mistress of House, p.31; Robins, Women, p.43f., 151f.; Robins, in: Images of Women, pp.73-6.

47

During the reign of her husband, Thutmosis II, Hatshepsut is visible performing cult activities throughout

Karnak with Neferure behind her. Bryan, Mistress, p.32; Robins, Women, fig.2.

48

As witnessed through the titulary of Senenmut, who serves as steward for all three, and as tutor to

princess Neferure, Hatshepsuts daughter and successor as gods wife. Bryan, Mistress, p.32. Cf.

Dorman, Senenmut, pp.201-11 for a list of Senenmuts titles, these three positions fall on pp.204-6.

10

These actions certainly make it plausible that Hatshepsut may have been able to utilize

her authority as GWA to consolidate a power base and create officials especially loyal to

her.

Although the idea that there were competing factions or parties, some that

were loyal to Hatshepsut and others who sided with the young Thutmosis III, has

generally been discarded,

49

Dziobek has recently revived the concept that there was some

type of bureaucratic involvement in Hatshepsuts rise.

50

According to Dziobek, faced

with a young child (Thutmosis III) as the king upon the death of Thutmosis II and a

potential crisis, the highest officials of the time came together and made a state

decision for the benefit of the entire country. Fearful of lengthy queen-regency and not

wishing to bring in a non-royal as Hatshepsuts new husband and co-regent for

Thutmosis III, these officials opted to install Hatshepsut herself as pharaoh. This

cabinet included men such as the vizier User, herald Intef, treasurer Djhuty, overseer of

granaries Minnakht, and steward Senenmut.

51

Dziobek believes that the late date of

Hatshepsuts proscription, as well as the fact that several of her officials, and also their

descendants, continue to serve under Thutmosis III, indicates that Hatshepsut was not a

usurper to throne. Rather, it further supports the idea that they helped to orchestrate

Hatshepsuts rise only out of necessity, and also ensured a smooth transition from the

regency of Thutmosis III to the co-regency with Hatshepsut and back again to his

49

Thus Redford, who is careful to distinguish his own theories from those of, for example, Hayes (CAH

II.1, pp.318-9). Cf. Redford, History and Chronology, Ch.4, p.57-87, esp. pp.62-5, 77. See on this issue

also Dorman, Senenmut, pp.10-14.

50

Dziobek, in: Thebanische Beamtennekropole, pp.134-6 and Denkmler, pp.131-48. Unless otherwise

noted, the statements made in the following paragraph all refer back to these pages.

51

The discussion of these men can be found in Dziobek, in: Thebanische Beamtennekropole, pp.132-4 and

Denkmler, pp.132-43. User and Minnkaht are included in the corpus of officials used in the present study.

See Ch.1, pp.79-87 and 121-32, respectively.

11

regency. For Dziobek, the implication is that Thutmosis III already had a well-established

elite formed at the court when the co-regency ended and Thutmosis III began his 32 years

of sole rule.

Much of the preceding discussion has focused on providing a brief review of

opinions concerning domestic developments within Egypt prior to the sole reign for

Thutmosis III. Yet, another important aspect of this time period was the military

activities. It has long been recognized that the expulsion of the Hyksos ushered Egypt

into a new phase militarily.

52

Generally referred to as Egypts Imperialistic Age, the

kings who were most involved in expanding Egypts influence over portions of Syria-

Palestine were Thutmosis I and Thutmosis III, and while essentially every pharaoh

campaigned in Nubia, it was Thutmosis I who finally removed the Kushite threat.

53

It is

also important to mention that certainly prior to the sole reign of Thutmosis III, and most

likely for some time thereafter, the evidence for a clear Egyptian presence, in the form of

garrison-towns and troops, in Syria is minimal, though the opposite was probably true for

the region of Gaza.

54

This is quite different from the Egyptian presence in Nubia, which

immediately resulted in the refurbishment of Middle Kingdom fortresses, and erection of

52

See the literature cited in notes 14-15 above. However, it should be noted that more recently Redford has

taken the view with regard to Syria-Palestine that prior to year 22 of Thutmosis III, i.e., the beginning of his

sole reign, the extent of Egyptian involvement in the early 18

th

Dynasty was modest and in many respects

traditional. Redford, Wars, p.185.

53

Kemp, in: Imperialism, pp. 7-57 and 284-297; Morris, Imperialism, pp.30ff., 48ff., 68ff., 115-29;

Redford, Egypt, Canaan and Israel, pp.148-62; Redford, Wars, pp.185-94.

54

Redford, Egypt, Canaan and Israel, pp.192-213; Redford, Wars, pp.185-94, 255-7; Morris, Imperialism,

Ch.2 pp.38ff., 136ff.; Murnane, in: Essays te Velde, pp.251-8. In Syria, this in fact does not clearly occur

until the Ramesside Period, or perhaps late 18

th

Dynasty around the reign of Horemheb; cf. Redford, Egypt,

Canaan and Israel, pp.203-7; Morris, Imperialism, pp.268ff., 339-42. However, Morris (pers. comm.) also

argues for a larger Egyptian presence in Syria-Palestine than is usually assumed during the reign of

Thutmosis III. She bases this in large part on the Horemheb Decree, interpreting his repeal of the practice

of garrisoning and providing for troops up and down the Nile River during the reign of Thutmosis III as

applying to foreign policy as well. For a recent translation of the text, see Murnane, Texts, pp.235-40, the

relevant section is on p.237f.

12

new temples and associated towns.

55

In general the campaigns of Thutmosis I into northern Syria have been viewed as

little more than skirmishes and a hunting expedition in Niye.

56

However, Redford has

taken a different approach. He characterizes Thutmosis Is expedition to the Orontes

River and northern Syria as a resuscitation (if not an outright innovation) of a concept of

military confrontation which involves something more than a mere razzia or punitive

attack.

57

Whether due to Thutmosis Is premature death, as Redford would interpret, or

because Thutmosis Is campaign still accomplished little more than a raid, there is little

doubt that it was not until after year 22 of Thutmosis III that the Egyptians could be said

to be in any way in control of large portions of Syria-Palestine.

58

Almost immediately upon starting his (second) regency in year 21, Thutmosis III

began a program of constant military activity that lasted throughout most of his thirty-two

years of sole rule.

59

Of all the pharaohs of the early to mid-18

th

Dynasty, Thutmosis III

was the most prolific in acquiring and retaining control of territory throughout the Near

East.

60

This new era of expansion necessitated a larger and more organized army than

Egypt had ever had, resulting in what Helck described as homines novi taken from out of

the military and placed in civil and court positions.

61

Helck also suggested that despite

55

Kemp, in: Imperialism, pp. 21-57 and 284-297; Morris, Imperialism, pp.68ff., 180ff.; OConnor, in:

Social History, pp.255ff.

56

For example, Bryan, in: Oxford History, p.234.

57

Redford, Wars, p.186.

58

As Redford strongly states; cf. Redford, Wars, p.193f., pp.255-7.

59

Morris, Imperialism, pp.115ff.; Redford, Egypt, Canaan and Israel, pp.155ff.; Redford, Wars, esp.

pp.191ff.; Weinstein, BASOR 241, pp.10-15.

60

Redford provides the most recent, and excellent, discussion of Thutmosis IIIs campaigns, the changing

nature of the relationship between Egypt, Syria-Palestine and the contemporary Near Eastern powers, and

comments of Thutmosis IIIs administration of the areas under Egypts sway; cf. Redford, Wars.

61

Most recently Bryan, in: Oxford History, p.247. Helck was the first to undertake a study of the

development and changes within the military during the 18

th

Dynasty, and his conclusions have essentially

been followed; cf. Helck, Einfluss, esp. pp.34ff.

13

the stronger military presence, during Thutmosis IIIs reign the top administrative

officials were primarily promoted up out of the priestly ranks, especially those of the

Amun temple at Karnak.

62

Furthermore, he asserted that familial connections were

important to determining who was granted high civil office.

63

Dziobek seems to have

affirmed this idea to some extent, suggesting that the elites paid increasing attention to

the continuation of their own families positions of power during this period.

64

More

recently, it has been suggested that although Thutmosis III had the established elite at his

disposal, to some degree he also made use of the men who accompanied him on his

campaigns.

65

Underlying all of these explanations is still the assumption that a division

existed between the established and the so-called new class of military elite in terms of

what types of offices they could hold. Thus, it is generally assumed that the highest

positions, such as vizier and overseer of the seal, were still reserved for men from

established families, while military officials could have court connections, but were not

involved in the administration of the palace per se.

66

Since the time of Helcks Verwaltung,

67

the view has been that the accession of

Amenhotep II in many respects revolutionized the makeup of the court. Helck argued that

there was an entirely clean break between the governments of Thutmosis III and

Amenhotep II, in which Amenhotep II eschewed the elite families of his father in favor of

childhood friends who were sons of his nurses, and children of the court.

68

He also

62

Helck, Verwaltung, pp.537-8.

63

Helck, Verwaltung, pp.537-8.

64

Dziobek, Denkmler, p.147.

65

Bryan, in: Thutmosis III, forthcoming.

66

Bryan, in: Thutmosis III, forthcoming; cf. Helck, Einfluss, pp.33, 41ff., 71f.

67

Helck, W., Zur Verwaltung des Mittleren und euen Reichs (Probleme der gyptologie 3), Leiden-Koln:

E.J. Brill, 1958. This massive volume, published in 1958, is still considered the standard work for the

period, despite the fact that it is largely out of date.

68

Helck, Verwaltung, pp. 537-8; Helck, Einfluss, pp.35-6, n.1, 66-71.

14

concluded that men who served in the military campaigns of Thutmosis III and

Amenhotep II, and became civil officials following their soldierly exploits, were the

benefactors of similar royal favor, and that they strove to conceal their military origins.

69

Der Manuelians work on the reign of Amenhotep II led him to the conclusion that

several military officials who began under the reign of Thutmosis III were kept on by

Amenhotep II because he recognized their worth and experience.

70

However he also

concurred with Helck that Amenhotep II had a newly initiated policy of surrounding

himself primarily with officials he had grown up with and knew personally.

71

The foregoing review has attempted to bring out the complexities of the situation

leading up to and, to some extent, during the period of Thutmosis IIIs sole reign to the

early years of Amenhotep II. The various conclusions that have been made about the

nature of the administration during this period, and how officials acquired and retained

their positions are precisely those that are being challenged in the current study.

III. Prosopographical Studies

As a study of both an individuals life and career, prosopography is an historical

inquiry that should encompass both genealogical and biographical research. However,

many prosopographical studies seem either to concentrate on only one of these, while the

second is afforded little or no serious attention, or to treat them as essentially separate

entities. This naturally results in a rather one-sided discussion, with the focus often on the

titles that pertain to an area of administration, and a lengthy list of officials appended to

69

Helck, Einfluss, p.71-3.

70

der Manuelian, Amenophis II, p. 168.

71

Der Manuelian, Amenophis II, p. 168.

15

the larger work.

72

A main goal of this dissertation is to reintegrate the different types of

information such that the career and family of each official can be presented as fully as

possible. This will make it possible to more clearly define the means by which officials

obtained office and begin to answer questions concerning the composition of the

government and possible tensions between well-placed families and the king.

Although the current examination represents a divergence from more traditional

prosopographical studies, it nonetheless draws upon the methodologies developed by this

earlier work. Thus, a review of some of these, especially those that deal with the New

Kingdom, is necessary. Since Helcks Verwaltung

73

is still considered the standard work

on the subject of the New Kingdom administrative structure, it will be examined first.

Following this is a discussion of more recent approaches, such as those of Bierbrier,

Kitchen, and Davies.

74

Helcks monumental Verwaltung in many ways set the tone for subsequent

discussions of the administration and the officials who formed it. The Verwaltung is

divided up into chapters that clearly demonstrate that although it is a book about the

administration of the Middle and New Kingdoms, it deals with selective portions of the

administration. Helck examines what are generally perceived as the main areas of

72

The classic example is Helcks Verwaltung. In a similar vein see also Chevereau, Prosopographie du

ouvel Empire; Englemann, ZS 122, pp.104-137; Gratien, Prosopograhie des ubiens; Kees,

Priestertum; Kees, Hohenpriester; Schulman, MRTO; Strudwick, Administration. Even the

prosopographical studies on which my own methodology is modeled follow this model to some extent; cf.

Davies, Whos who; Vittmann, Priester und Beamte. It is also a common method of presenting the officials

in a lager study on a particular kings reign, although in his case the abbreviated treatment is quite

understandable; cf. Bryan, Thutmose IV; der Manuelian, Amenophis II.

73

Helck, W., Zur Verwaltung des Mittleren und euen Reichs (Probleme der gyptologie 3), Leiden-Koln:

E.J. Brill, 1958. In addition, Helck deals with New Kingdom involvement in the Near East, the military in

the 18

th

Dynasty, and New Kingdom temple economy, respectively, in his monographs Beziehungen

gyptens, Einfluss and Materialien. Likewise, his Beamtentiteln is still a major resource for Old Kingdom

research.

74

Bierbrier, Late ew Kingdom; Bierbrier, in: Village Voices, pp.1-7; Davies, Whos Who; Kitchen, TIP.

16

administration, i.e., vizierate, treasury, palace and land.

75

Within each section he presents

a discussion of the titles, focusing on how they are defined, and the functions attached to

them.

76

Helck uses the titles to discuss the positions themselves, bringing in the officials

who held them when documenting inscriptions that demonstrate the variations in the

titles, or what duties were attached to it. In the few cases in which Helck includes the

people who held these offices in his analysis of the positions, the resulting discussion is

essentially chronological and without much additional information about the officials or

their families.

77

Helcks prosopographical notes on particular offices and the officials who held

them are a telling example of what are often considered the most important offices, and

generally the most discussed.

78

In the Verwaltung, the positions of vizier, treasurer, high

steward, overseer of granaries, overseer of the treasury, and mayor of Thebes are all

treated, despite the fact that the earlier portions of the Verwaltung in fact cover several

other areas and titles within the government. Helck also included a chapter providing

basic genealogical information for the officials treated in the prosopography. This method

of dividing the discussion and presenting a prosopography based foremost on titles has

since become the standard in the scholarly literature that deals with overall studies of the

government, the administration during a particular kings reign, and investigations on the

development of an area of administration or specific title over time.

79

75

Noticeably left out due to their treatment elsewhere, are the military (cf. Helck, Einfluss) and priesthood

(cf. Kees, Priestertum).

76

Helck, Verwaltung, Chapters 1-20, pp.1-285.

77

I.e., mayor (HAty-a), butler (wbA), fan-bearer and standard-bearer (TAy xw, TAy srit)

78

Helck, Verwaltung, Chapters 21-22.

79

See the literature cited in notes 3-6 above.

17

In the summary that completes the volume,

80

Helck makes several sweeping

conclusions about the evolution of New Kingdom administration. Some have been borne

out by subsequent studies,

81

while others have been modified.

82

A suggestion made by

Helck that is especially significant for the current study is one that has essentially been

accepted and integrated into following discussions about New Kingdom government.

This is Helcks conclusion that there is a sharp break between the administrations of

Thutmosis III and Amenhotep II.

83

He posited that up through the reign of Thutmosis III

administrative officials were primarily promoted up out of the priestly ranks, family

retention of position was not unusual, and officials that did not come from an established

family were uncommon. In contrast, Amenhotep II surrounded himself with boyhood

friends from the court who thus had personal relationships with their king. The theory

that at this time there was an introduction of new men into an established system has had

a great impact on all studies that came after Helck, and while some have admitted that

Helcks characterization is probably too simplistic, none have yet offered alternatives.

84

Similar conclusions that have come from Helcks volume on military influence during the

18

th

Dynasty,

85

include the theory that military officials came from a lower social strata,

could not pass on their positions, and are not found in ranks outside the military later in

80

Chapter 23, pp.532-47.

81

For example, Helcks remark that a reorganization of the administration was undertaken following the

expulsion with the Hyksos that included the creation of the office kings son of Nubia. Cf. Helck,

Verwaltung, p.537. In confirmation of this, see, for example van den Boorns comments in Duties,

pp.339ff. (obs.19), 349f., 368ff.

82

Such as Helcks assumption that the growth of the military during Thutmosis IIIs sole rule was in part

due to a reaction against the passive reign of Hatshepsut; cf. Helck, Verwaltung, p.537.

83

Helck, Verwaltung, pp.537-8.

84

The simplicity of Helcks statements has, to some extent, already been pointed out, though no

alternatives have yet been offered; cf. der Manuelian, Amenophis II, p.168 (who nonetheless essentially

follows Helck), and to a greater degree by Bryan, Thutmose IV, pp.353 ff.; Bryan, in: Thutmosis III,

forthcoming.

85

Helck, Der Einfluss der Militrfhrer in der 18. gyptischen Dynastie, (Untersuchungen zur Geschichte

18

life, while the so-called front soldiers moved into court and palace positions and hid

their military backgrounds.

86

Since the Verwaltungs publication in 1958 a significant amount of new material

has come to light through excavation, publication, and new research, all of which makes

Helcks work in need of re-assessment and revision.

87

Other scholars have taken this on

for particular offices, but none have yet attempted a wider-scale project for the New

Kingdom that encompasses multiple offices and officials.

88

A main goal of this study is

to reevaluate and re-examine the trends and changes that Helck suggested occurred

during the Thutmosis III Amenhotep II period. Although the system of government

may appear to be working along a particular line on the surface, by focusing on the

officials themselves, and utilizing a multi-dimensional examination that studies how

officials attained their positions, as well as their overall careers and their families,

nuances are more likely to be noticed that provide insights into the underlying framework

of job acquisition and the bureaucracy.

Although Helcks Verwaltung is the most relevant work to the present effort in

terms of time period and subject matter, there are other, more recent, prosopographical

studies whose methodologies are much closer to that being employed here. They each

follow the approach that the ability to draw historical conclusions from prosopographical

research relies on extensive genealogies, an understanding of the kinship terminology,

und Altertumskunder gyptens 14), Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs, 1939.

86

Helck, Einfluss, pp.28-33, 71-3.

87

Warbuton comments that the work is out of the[sic] date and based on speculative interpretations about

the character of the Egyptian state and the degree to which conclusions can be drawn from titles.

Warbuton, in: Oxford Encyclopedia Vol.3, p.583. Likewise, in a recent study on New Kingdom Memphis,

Martin has again drawn attention to the lack of a comprehensive New Kingdom prosopography for the

whole country. Martin, in: Abusir and Saqqara, pp. 102-3. See also his n.19 for a list of some publications

which have produced prosopographical information for the New Kingdom.

88

For example, Bohleke, Double Granaries; Bryan, ARCE 1981; Eichler, Verwaltung des Hauses des

19

and connections between private individuals and known historical figures through which

to establish a firm chronology.

89

Several of the more germane include those by

Vittmann, Kitchen, Bierbrier, and Davies. These will now be reviewed.

Vittmann undertook a genealogical and prosopographical study of priestly and

civil officials in Saite period Thebes.

90

He states in his introduction that while he had

intended to include all officials from the Saite Period, he was restricted to focusing on

Theban-based individuals due to the genealogical information available.

91

Further, the

methodology Vittmann followed allowed for the presentation of only those officials for

which extensive genealogical information was known, except in cases where their

inclusion was necessary for chronological purposes of tracing the particular office

through the Saite Period.

92

Thus, he omitted persons who were mentioned perhaps only

once with an obscure title and no filiation.

93

Vittmanns criteria still allowed him to

examine not just the highest office holders, such as viziers and high priests, but several

lower level families as well. The results of his investigation primarily concern

establishing genealogies of the various officials he was able to document. However, it

also produced important socio-historical information about the relationship between these

officials and the royal line from Osorkon II through Takelot III.

94

In addition, Vittmann

was able to demonstrate the ability of these Theban families to retain their titles, both

priestly and mayoral, though several generations.

Amun; Gnirs, Militr; van de Boorn, Duties.

89

Most explicitly stated by Bierbrier, in: Village Voices, p.1; Bierbrier, Late ew Kingdom, pp.xiii-xvi.

90

Vittmann, G. Priester und Beamte im Theben der Sptzeit. Genealogische und prosopographische

Untersuchungen zum thebanischen Priester- und Beamtentum der 25. und 26. Dynastie. Beitrge zur

gyptologie 1 Wien: Afro-Pub, 1978.

91

Vittmann, Priester und Beamte, p.1.

92

Vittmann, Priester und Beamte, pp.2-3.

93

Vittmann, Priester und Beamte, p.2.

94

Though, as Bierbrier notes in his review, Vittmann also tended to treat each family grouping in isolation

20

Kitchens work on the Third Intermediate Period (1100-650 B.C.) is one of the

most important studies on this difficult phase of Egyptian history.

95

He examined the

royal families, as well as the elite officials and families that were connected with them, or

represented the beginnings of other royal lines. The often confusing and overlapping

nature of the families and rulers present during this time, as well as the often concomitant

dynasties based in different cites or areas of Egypt, made Kitchens task enormously

complex. Especially important for his study were the high priests of Ptah in Memphis, the

Theban high priests of Amun, and other high-ranking dignitaries from Thebes and

Heracleopolis. For the Theban high priests of Amun and for the some of the Tanite kings

in the 21

st

Dynasty, much of the information on family relationships came from the

women involved. Kitchen was able to establish a relative chronology through his

reconstruction of the family lines, as well as the lines of succession in the offices held by

the families. By combining this relative chronology with the few absolute dates known

for some of the kings and elites, Kitchen was able to produce a much clearer version of

events for the Third Intermediate Period in terms of actual regnal lengths and the roles

that kings and various important officials (and their wives) played during this period.

96

His collection and use of the massive amount of material he gathered thus enabled him to

reconstruct the basic chronology of the 21st-25th Dynasties, and therewith to present an

historical outline.

97

Bierbriers studies

98

of some of the families represented in the Late New

rather than to construct an integrated schema. Bierbrier, BiOr 36, pp.306-9 with Table 1.

95

Kitchen, K.A., The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt, 110 - 650 B.C., Warminster: Aris & Phillips,

1986.

96

Kitchen, TIP, esp. Part I, Part III, Part IV.

97

Kitchen, TIP, p.xi.

98

Bierbrier, M.L. Terms of Relationship at Deir el-Medna, JEA 66 (1980), pp. 100-107; Bierbrier, M.L.

21

Kingdom at Deir el-Medina was undertaken to determine more exactly the possible

maximum lengths of some of the reigns in this period [Dynasties 19-26] and to illuminate

certain historical trends with regard to the priestly class.

99

The detailing of numerous

family histories for both the noblemen of Dynasties 19-25 and the workmen of Deir el-

Medina allowed Bierbrier to comment on two essentially different but equally important

broader issues: the accession of Ramesses II and the method of succession to office

during the Ramesside and early Third Intermediate Period.

Based on these histories, Bierbrier was able to contribute a generational timetable

to the period between Ramesses II and XI, allowing him to make significant contributions

to the discussion on the accession of Ramesses II.

100

In addition, he was able to

demonstrate that high offices during the Ramesside Period were essentially hereditary.

While occasionally these families fell out of power, they almost always regained their

standing within the given career at a later point, often through marriage. Moreover, these

positions were remembered down the line as later relatives claimed the right to be

installed in a particular office based on their family.

101

In his study of the workmen,

Bierbrier concludes that the hereditary method of succession did not stop with the

nobility, but also made its way into the lower levels of society, as demonstrated by the

position of chief workman on the right and left, which were each passed down through

The Late ew Kingdom in Egypt (c. 1300-664 B.C.): a genealogical and chronological investigation,

Warminster: Aris & Phillips, 1975; Bierbrier, M.L. Genealogy and Chronology: Theory and Practice, in:

R.J. Demare and A. Egberts (eds.), Village Voices: Proceedings of the Symposium "Texts from Deir el-

Medna and Their Interpretation", Leiden, May 31-June 1, 1991 (CNWS 13), Leiden: Centre of Non-

Western Studies, 1992, pp.1-7.

99

Bierbrier, Late ew Kingdom, p.xii.

100

Bierbriers findings enable him to discard the 1304 date, while lending further support to the 1279, and

1290 dates for Ramesses IIs accession; cf. Bierbrier, Late ew Kingdom, pp. 109-113.

101

Bierbrier, Late ew Kingdom, pp.1-18, 113-14.

22

multiple generations, and had connections with the office of deputy.

102

Bierbriers work clearly shows that when family and titular histories are examined

in conjunction, they become a valuable asset for investigating the bureaucratic system, as

well as providing further information on the amount of time that elapses between reigns

and even dynasties. Indeed, as Bierbrier states in his conclusion to The Late ew

Kingdom,

Apart from chronological information, the study of the careers of

individuals and families reveals certain interesting data about the officials

and the descent of offices in the late New Kingdom.

103

Davies prosopographical study on the numerous families of workmen known

from Deir el-Medina was aimed at examining the pedigrees of the major families from

the village of Deir el-Medina.

104

He was able to demonstrate that these offices were also

largely hereditary in nature, and extremely intertwined among the various families. As a

result, a much clearer picture was gained of the successions of the office holders, and

their functions.

105

Davies was also able to connect several officials and families with the

reigns of particular kings, providing better chronological information on the Late New

Kingdom.

106

The foregoing review of previous proposopographical work demonstrates that the

current study is not without scholarly predecessors. Although I am adapting the

methodologies developed and employed in the work of Bierbrier, Kitchen and others, a

102

Bierbrier, Late ew Kingdom, pp.19-44, pp. 113-116.

103

Bierbrier, Late ew Kingdom, p.113. Vittmann also found this to be the case, as for example in the case

of the overseer of the gods wife, where it became apparent that sons of apparently low ranking officials

were able to attain this rather upper level position, perhaps due to royal favor; cf. Vittmann, Priester und

Beamte, p.202.

104

Davies, Whos Who, p.xxiii.

105

This is especially true in the case of the scribal families; cf. Davies, Whos Who, Appendix A, pp.123-

23

fundamental basis for the research remains Bierbriers assertion that the ability to draw

historical conclusions from prosopographical investigation depends on the ability to

establish firm genealogies and chronological connections that connect the families with

known historical figures.

107

I am adding to this the assertion that in order to contribute

significantly to our socio-historical knowledge of ancient Egypt, the careers of the

officials examined must be considered in tandem with their family backgrounds. Linking

together these three topics will, it is believed, enable us not just to ask but also to answer

questions revolving around how offices were transmitted before, during, and after the

transition between kings.

IV. Methodology

Despite the narrow chronological period being studied, there is an extremely rich

body of data available within the cultural material belonging to the officials themselves,

specifically information found in tomb and shrine inscriptions and decorations, statues,

stelae, funerary cones and equipment, papyri and graffiti. While collecting and examining

this data, the titular, autobiographical and genealogical information contained within

these sources was always of primary interest. The quantity and clarity of these three types

of information helped to determine which officials to include for examination in this

dissertation. It must also be stated that the Theban tombs, which represent a significant

percentage of the overall data sources, were often unfinished in antiquity and are today in

varying states of preservation. This is a limitation of the data that is unavoidable and has

the result that in some cases our knowledge of an officials family and career would be

142.

24

substantially increased had the tomb autobiography or duty-related scenes been extant or

less damaged.

The original data set that was compiled contains every official known or thought

to have served during the Thutmosis III Amenhotep II period, and the list generated

includes over 100 individuals.

108

Each official was initially given the same treatment,

wherein all the available information about an official was collected. As mentioned

above, the material comes from both monumental and portable artifacts. The collection of

the data involved not only textual documentation, but also required particular attention to

the way in which these texts were displayed, namely, the associated and supplementary

decoration in tomb scenes, and the type and placement of other inscribed artifacts within

tomb, temple or secondary chapel. For Theban tombs, which the majority of the

examined officials owned, an eight-month field season was undertaken in order to