Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Impact of ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 On Standardisation of Social Responsibility-An Inside Perspective

Uploaded by

Janak Valaki0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views14 pagesThis paper aims to investigate what views ISO member body delegations and invited participants had about the divergence from the meta-standard approach towards a guidance standard. It will shed light on the perception of ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 that are held by standard developers.

Original Description:

Original Title

1-s2.0-S0925527307003106-main

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis paper aims to investigate what views ISO member body delegations and invited participants had about the divergence from the meta-standard approach towards a guidance standard. It will shed light on the perception of ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 that are held by standard developers.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views14 pagesThe Impact of ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 On Standardisation of Social Responsibility-An Inside Perspective

Uploaded by

Janak ValakiThis paper aims to investigate what views ISO member body delegations and invited participants had about the divergence from the meta-standard approach towards a guidance standard. It will shed light on the perception of ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 that are held by standard developers.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 14

Int. J.

Production Economics 113 (2008) 7487

The impact of ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 on standardisation of

social responsibilityan inside perspective

Pavel Castka

a,

, Michaela A. Balzarova

b

a

Department of Management, University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch, New Zealand

b

Lincoln University, Christchurch, New Zealand

Accepted 20 February 2007

Available online 13 November 2007

Abstract

Following a growing interest in corporate social responsibility, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

announced plans for development of the ISO 26000guidance standard for social responsibility. Despite initial signals

that ISO 26000 will be built on the intellectual and practical infrastructure of ISO 9000 and ISO 14000, the Advisory

Group on Social Responsibility set a different direction: a guidance standard and not a specication standard against

which conformity can be assessed. This paper aims to investigate what views ISO member body delegations and invited

participants in international standardisation of social responsibility had about the divergence from the meta-standard

approach towards a guidance standard. To answer the research question, the discussions at the ISO International

Conference on Social Responsibility, where ISO member body delegations and approximately 40 invited organisations

commented on this matter, have been analysed. As a result of this understanding, not only will insight into the rst steps of

standardisation of social responsibility be provided, but it will also shed light on the perception of ISO 9000 and ISO 14000

that are held by standard developers.

r 2007 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: ISO 26000; ISO 9000; ISO 14000; Corporate social responsibility; Management systems; Standardisation

1. Introduction

In the past, companies were facing growing

demands from customers, who hugely impacted on

the way they operated, whereas todays demands

have shifted toward addressing a wider spectrum of

stakeholders (Rosam and Peddle, 2004). This

evolution of business and societal environment is

bringing quality management closer with other

elds, such as corporate social responsibility

(CSR), corporate governance and business ethics.

Many scholars have started to point towards this

evolutionary trend and some of them argue that for

quality to remain a viable concept in the 21st

century, it must embed more deeply and rmly the

issues of virtue (Ahmed and Machold, 2004). As

CSR is gaining its momentum, other scholars point

to obvious parallels in quality and CSR evolution

(Peddle and Rosam, 2004; Waddock and Bodwell,

2004; Castka et al., 2004a, b) as well as assert the

convergence of these two elds of study.

Indeed, this convergence is happening at many

levelsone of which is the arena of international

ARTICLE IN PRESS

www.elsevier.com/locate/ijpe

0925-5273/$ - see front matter r 2007 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2007.02.048

Corresponding author. Tel.: +64 3 364 2987x8617;

fax: +64 3 364 2020.

E-mail addresses: pavel.castka@canterbury.ac.nz (P. Castka),

balzarom@lincoln.ac.nz (M.A. Balzarova).

standardisation. In the 1980s, following on from

British Standard BS 5750, the International Orga-

nization for Standardization (ISO) developed ISO

9000a generic quality management systems stan-

dard (MSS), which became accepted globally.

Followed by the ISO 14000 environmental manage-

ment system in 1996, a similar scenario has been

happening with the social responsibility eld. In

2004, ISO announced a new work item: ISO 26000-

guidance standard for social responsibility to be

introduced by 2008. The pre-standardisation pre-

paratory work suggested that the impact of ISO

9000 and ISO 14000 on the standardisation of social

responsibility is likely to be substantial. ISO/

Bulletin (2002) informed that ISO standard for

social responsibility would evolve from quality and

environmental standards (ISO 9000 and ISO

14000). Specically, the ISO Committee on Con-

sumer Policy (ISO COPOLCO, 2002) recommended

a meta-standard approach to the social responsi-

bility standard against which rms could self-

declare compliance or could seek certicates from

authorised third parties. However, the Advisory

Group on Social Responsibility, which was estab-

lished as a result of Resolution 78/2002 and given

the purpose of determining whether ISO should

proceed with the development of ISO deliverables in

the eld of corporate social responsibility, recom-

mended that a guidance document, and therefore

not a specication document against which con-

formity can be assessed should be developed (ISO/

AG/SR, 2004a, b). As the next step in this pre-

standardisation work, ISO held the ISO Interna-

tional Conference on Social Responsibility and

invited ISO member body delegations and other

international organisations to debate recommenda-

tions made by the Advisory Group on Social

Responsibility.

We conducted our research at this stage of

the process of the social responsibility standardisa-

tion, i.e. before the process of the development

of ISO 26000 started. Our aim was to investigate

the question what impact has ISO 9000 and

ISO 14000 had on the direction of the develop-

ment of ISO 26000 guidance standard for social

responsibility? In particular, we aimed to investi-

gate what views ISO member body delegations

and invited participants had on the proposal to

move from the meta-standard approach towards a

guidance standard. To answer our research ques-

tion, we analysed the discussions at the ISO

International Conference on Social Responsibility,

where ISO member body delegations and approxi-

mately 40 invited organisations commented on this

matter.

The paper has the following structure. Firstly,

we look at ISO MSS and discuss the situation

in this area. Secondly, we shift the focus towards

social responsibility standardisation and present

recent developments within the ISO related to

social responsibility standardisation. Thirdly, we

describe in detail our research engagement.

Fourthly, the results are presented, analysed

and concluded with a discussion of social

responsibility standardisation, limitations of

our research and implication for future develop-

ments in the arena of social responsibility standar-

disation.

2. ISO management systems standards: state-of-the-

art

Uzumeri (1987) explains that in the late 1980s

standards bodies made major breakthroughs in

management standardisation by developing MSS.

These standards emerged in elds as diverse as

product quality, nancial controls (the COSO

Framework), white-collar crime prevention and

environmental management. The most prominent

are ISO MSS, namely ISO 9000 and ISO 14000. By

developing this voluntary set of standards, ISO

aimed to facilitate international exchange of goods

and services as well as simplify business-to-business

operations. In order to be certied, organisations

have to comply with the requirements described in

these standards. This compliance is veried by a

third-party audit carried out by an accredited

certication agency.

ISO 9000 is designed as an MSS, i.e. a system to

establish policy and objectives as well as a way to

achieve these objectives. Uzumeri (1987) refers to

ISO 9000 as a meta-standarda standard based on

a list of design rules to guide the creation of entire

classes of management systems. Since its introduc-

tion in 1987, ISO 9000 has been revised in 1994 and

2000 (Kartha, 2002; Laszlo, 2000; Struebing, 1997).

Of paramount importance is the 2000 revision that

further strengthened the focus on a systems

approach to management, which was less empha-

sised in previous versions. The revised ISO

9000:2000 family of standards includes a model

of a process-based quality management system and

a much stronger emphasis on systems nature of the

standard. Furthermore, ISO 9000:2000 promotes a

ARTICLE IN PRESS

P. Castka, M.A. Balzarova / Int. J. Production Economics 113 (2008) 7487 75

set of eight principles (customer focus, leadership,

involvement of people, process approach, systems

approach to management, continual improvement,

factual approach to decision making and mutually

benecial supplier relations), which form a basis for

the quality management principles within the ISO

9000 family and beyond. ISO 14000, introduced in

1996 and revised in 2004, shares the same approach

and principles with ISO 9000. Moreover, both

standards contain appendices that directly demon-

strate the link between respective clauses of these

standards.

Both standards have spread globally. In 2004, the

ISO reported over 670,000 ISO 9000 certicates in

154 economies and over 90,000 ISO 14000 certi-

cates in 127 economies (ISO/Survey, 2004). Indeed,

many inuential organisations adopted the

standard, despite the fact that ISO 9000/14000

are voluntary and not a mandatory directive

(Brunsson and Jacobsson, 2000). This in turn

forced others (directly or indirectly) to adopt ISO

standards. Indeed, the research into the diffusion

of ISO 9000/14000 standard demonstrates that the

role of multinational networks here is crucial

they are viewed as key actors responsible for

coercive isomorphism (Guler et al., 2002; Neumayer

and Perkins, 2005; Corbett and Kirsch, 2001).

The diffusion mechanisms usually involve contrac-

tual requirements imposed by multinationals, the

industry or key players in the supply chain.

Cohesive trade relationships between countries

(Guler et al., 2002) play a similar role. In the

domestic context, the number of past adoptions,

share of manufacturing GDP and level of education

are positively correlated with the adoption of ISO

9000. However, bureaucracy and/or corrupt reg-

ulatory interventions by governments are reported

as key deterrents in the diffusion (Neumayer and

Perkins, 2005). Hence this popularity of the

standard does not necessarily originate from its

appropriateness. This is one of the major criticisms

of ISO 9000. ISO 9000 is often imposed upon

organisations and organisations are also seen to be

opportunistic in pursuing certication to increase

sales rather than to improve quality (Abraham

et al., 2000).

Related to previous discussion is the question

whether ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 actually bring any

value for certied organisations. Many studies

strongly advocate for the benets that organisations

gain from ISO 9000 certication (Sharma, 2005;

Briscoe et al., 2005). For instance, Poksinska et al.

(2003) summarise the following benets stemming

from ISO 9000 and ISO 14000:

Internal performance benets (cost reductions,

environmental/quality improvements,

increased productivity, improved employee

morale)

Relations benets (improved relations with

communities and authorities)

External marketing benets (improved corpo-

rate image, increased market share, increased

customer satisfaction, increased on-time deliv-

ery)

However, recent discussions on ISO 9000 (both

academic and from practitioners) report contra-

dictory and ambiguous ndings and opinions. For

instance, van der Wiele et al. (2005) report

improvements in companies perception of the ISO

9000 standard, whilst Casadesu s and Karapetrovic

(2005) argue that benets that organisations obtain

from the ISO certication are eroding. Corbett et al.

(2005) found that ISO 9000 certication leads to

improved nancial performance measured by return

on asset. On the other hand, studies set up to

conrm that the market values ISO 9000 (Martinez-

Costa and Martinez-Lorente, 2003; Aarts and Vos,

2001) did not reveal any linkage. In a similar vein,

Corbett and Klassen (2006) argue that the link

between nancial performance and environmental

management is inconclusive after more than three

decades of research. More important is to look at

factors moderating successful implementation. Here

some studies conclude that the ones who benet

from ISO 9000 are those who learn (Naveh et al.,

2004) and that the certication provides little

guarantee of high-performance outcomes unless it

is accompanied by transformational and transac-

tional change (Abraham et al., 2000; Briscoe et al.,

2005; Balzarova et al., 2006; Castka et al., 2004c).

This is further emphasised by Takakusa (2005), who

warns that the benets of ISO 9000 could be

constrained by the way different organizations

implement the QMS standard and how committed

they are to an ISO 9000-based system. Indeed,

organisations differ in sizes, have different structur-

al and infrastructural designs and ownership ar-

rangements. All of these factors inuence the

approach toward adoption of ISO 9000 standards.

This stems from the meta-standard nature of the

standard (Uzumeri, 1987), which is clearly a double-

edged sword: on the one hand it makes the standard

ARTICLE IN PRESS

P. Castka, M.A. Balzarova / Int. J. Production Economics 113 (2008) 7487 76

generic in nature and gives organisations freedom to

translate it into their unique settings. On the other

hand, the consistency and quality of this transla-

tion becomes problematic.

To assure this consistency, the ISO certication

process includes a third-party certication audit

carried out by an accredited verication body. The

aim is also to reduce the number of second-party

audits, assist organisations in creating networks and

facilitate the business-to-business operations. How-

ever, the credibility of certication has become

increasingly criticised by organisations, consultants

and members of the ISO community. For example,

Lal (2004) states:

Judging by the views expressed in various

forums, one cannot help but conclude that ISO

9000 certication has fallen short of expectations.

The main reason for laxity and malpractice in

ISO 9000 certication is that what was originally

meant to be a service to industry is increasingly a

business motivated by prot.

Lal (2004), similar to Seddon (2000), furthermore

summarises the weakness of the present system:

The commercial nature of the relationship

between the certier and the audited organisa-

tion

The technical competence of auditors

Accountability of the certication body to the

nal customers and end users of the audited

companys products and services

In conclusion, there is a large body of literature

on ISO 9000 and ISO 14000, which provides

rich evidence on various aspects of these two

standards. However, there seems to be one

signicant difference between empirical studies

(such as Briscoe et al., 2005; Casadesu s and

Karapetrovic, 2005; Corbett et al., 2005; Naveh

et al., 2004; van der Wiele et al., 2005) and

views expressed by practitioners (Dalgleish, 2005;

Lal, 2004; Seddon, 2000). Whereas the authors

of empirical studies in general agree that ISO

9000 certication is benecial (even Casadesu s

and Karapetrovic, 2005 conclude in this way

despite their overall criticism), many practitioners,

deriving from largely anecdotal evidence, argue

against ISO 9000 (Seddon, 2000) and claim

that ISO 9000 proves ineffective (Dalgleish,

2005).

3. Towards ISO 26000

With over a decade of delay after ISO 9000 and

shortly after the introduction of ISO 14000, the rst

attempts were made to provide standards for social

responsibility. Similar to quality, where a national

standard produced by the British Standards Institu-

tion (BS5750, 1987) led to an international stan-

dardisation of quality management, the rst social

responsibility standards were developed by the

National Standards Bodies in Australia, France,

Mexico, Japanto name but a few. Furthermore,

other standards outside National Standards Bodies

were developed, such as AA 1000 (1999) and SA

8000 (2001). In ISO/Bulletin (2002), the ISO

announced its intention to grasp the area of social

responsibility with further possibility to develop a

standard. Firstly, ISO formed the ISO Committee

on consumer policy (ISO COPOLCO), which

announced that a trio of ISO management stan-

dardsISO 9001, ISO 14001 and ISO corporate

social responsibility MSS (CSR MSS)would

support business efforts to show that an organisa-

tion cares about quality, environment and the social

effects of a production or activity (ISO COPOLCO,

2002). In their report, the committee has, amongst

other issues, recommended that (ISO COPOLCO,

2002):

ISO CR MSSs would constitute an internation-

ally agreed-upon framework for operationaliza-

tion of corporate responsibility commitments,

capable of producing veriable, measurable out-

puts. The ISO CR MSSs would build on the

intellectual and practical infrastructure of ISO

9000 quality MSSs and ISO 14000 MSSs, and the

momentum associated with close to one-half

million rms certied as compliant with these

standards. As with ISO 9000 and ISO 14000,

rms could self-declare compliance with the

proposed ISO CR MSSs or could seek certicates

from authorized third parties. It should be

emphasized, however, that ISO CR MSSs would

be insufcient by themselves to assure that a rm

has developed and implemented an effective CR

approach. Thus, ISO CR MSSs would be one

piecealbeit a fundamental building blockof

effective CR approaches.

Where ISO COPOLCOs report shows the link

between social responsibility standard, ISO 9000,

ISO 14000 and MSS approach, the lately formed

ISO Advisory Group on Social Responsibility

ARTICLE IN PRESS

P. Castka, M.A. Balzarova / Int. J. Production Economics 113 (2008) 7487 77

(AG SR) dismissed this intent and recommended a

guidance document, and not a specication docu-

ment against which conformity can be assessed

(ISO/AG/SR, 2004b):

for use by business and other organisations,

that emphasises results and performance im-

provement,

that adopts a common terminology in this area,

that assists organisations in effectively addres-

sing their social responsibilities in various

cultures, societies and environments,

that can complement other relevant instruments

and tools,

that is not intended to reduce the governments

authority to address the social responsibility of

organisations,

that is of use to business and other organisations

of all sizes,

that provides practical guidance on methods

and options for operationalising social respon-

sibility, identifying and engaging with stake-

holders, enhancing credibility in claims made

about social responsibility, that should be

written in clear and understandable language.

By this step, ISO 26000 has taken a different

approach in comparison to ISO 9000 and ISO

14000. Apart from a shift from the meta-standard

approach and from third-party certication, ISO

26000 has a much broader content (see Table 1

key elements). It not only gives guidance for

organisations to implement social responsibilities

(SRs), but also provides guidance on SR context,

SR principles and guidance on core SR subjects/

issues.

4. Research engagement

As a new standard for social responsibility

emerges, the inevitable question arises: is the

standardisation in social responsibility fundamen-

tally different from quality and environment? What

are the similarities and differences between quality,

environment and social responsibility? What can we

expect from social responsibility standardisation?

Apparent parallels can be identied that would

suggest that standards in social responsibility,

quality and environment should show certain

similarities. All of these concepts are somehow

elusive and multiple meanings and denitions

exist (Waddock and Bodwell, 2004; ISO/AG/SR,

2004a; Lockett et al., 2006). According to Waddock

and Bodwell (2004), this was a problem in the early

days of quality movement and consequently many

managers questioned whether quality was measur-

able and whether there was a business case for

qualitysimilarly to social responsibility. In other

words, these concepts are organisation and sector

specic and a standard needs to take this into

consideration. In the case of ISO 9000 and ISO

14000, a meta-standard approach provided a solu-

tion. ISO 26000 also aims to assist organisations to

deal with social responsibility and also aims to be

generic. Hence from the perspective of design, we

would expect that ISO 26000 would be built on the

ARTICLE IN PRESS

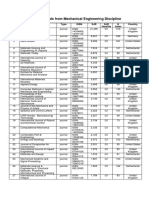

Table 1

A comparison of ISO 9000, ISO 14000 and ISO 26000

Standard ISO 9000 ISO 14000 ISO 26000

General description Quality management systems

standard

Environmental management

systems standard

Guidance on social

responsibility

Third-party certication Yes Yes No

Key elements Quality management

system

Management

responsibility

Resource Management

Product realization

Measurement, analysis

and improvement

Environmental policy

Planning

Implementation and

operation

Checking

Management review

The SR context in which

all organisations operate

SR principles relevant to

organisations

Guidance on core SR

subjects/issues

Guidance for

organisations

implementing SR

Note: Key elements of ISO 26000 are based on the Design Specication (ISO/TMB/WG SR N49, 2005).

P. Castka, M.A. Balzarova / Int. J. Production Economics 113 (2008) 7487 78

intellectual and practical infrastructure of ISO 9000

and ISO 14000, as well as be designed as a meta-

standard.

However, social responsibility requires a much

wider stakeholder base to be considered in compar-

ison to quality. The ISO 9000 quality management

standard is focused predominantly on the customer

and meeting the customers requirements. Social

responsibility, in contrast, considers stakeholders

ranging from customers to society in large. A

further difference is the control and feedback

mechanism. Quality is much more market driven

and customers can mostly directly assess the quality

of products and services. However, this is different

for social responsibility as well as environment. As

Terlaak (2002) asserts, for stakeholders to distin-

guish and to make informed decision on whether

ISO 14000-certied rms outperform in environ-

mental terms than those that are not certied is

difcult. Despite possible differences between qual-

ity and social responsibility, with respect to control

mechanisms of organisational quality and social

performance, there are clear similarities between

social responsibility and environment. Social re-

sponsibility performance, which is similar to

environmental performance, is often less transpar-

ent than quality. This suggests that environmental

and social responsibility standards should be result

based. However, ISO 14000 (developed through the

same standard development process as ISO 26000)

is designed as a process-based standard and not as a

result-based standard. Therefore, we expect ISO

26000 to be closely aligned with ISO 14000 and to

require organisations to develop their management

systems around their social responsibility aspects

and impacts. Similarly, we expect ISO 26000 to be

based on processes as ISO/AG/SR (2004b) state

that ISO has to recognise that it does not have either

the legitimacy or the authority to set social

obligations that are dened by governments.

The work on international standardisation in-

evitably brings with it a conict of interests and

principles (Hallstrom, 2004). In comparison to ISO

9000, the development of ISO 26000 requires a

much wider stakeholder base to be involved. This

includes stakeholders that have different expecta-

tions, benets and views on social responsibility

standardisation. Since the ISO process of interna-

tional standards development is based on a con-

sensus of involved parties, we expect that the nal

product, a guidance standard for social responsi-

bility, will reect this. The preceding review of the

literature on benets from ISO 9000 and ISO 14000

certication not only highlighted certain decoupling

of empirical ndings and practitioners perception

of ISO MSS, but also showed that practitioners are

rather doubtful about the empirical results. We

therefore expect that the standard development

agenda will be largely politically driven and that

participants will show contradictory views based on

their interests and personal beliefs.

This last point led us to an exploratory design for

this study. Hence, we aim to answer the what and

why questions stated previously. In our quest to

investigate the research question what impact has

ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 had on the direction in the

development of ISO 26000 guidance standard for

social responsibility?, we investigate what views

ISO member body delegations and invited partici-

pants (further referred to as standard developers)

had on the proposal to move from the meta-

standard approach towards a guidance standard.

We conduct this inquiry in the three research areas

(RAs) that capture the difference between the ISO

9000, ISO 14000 approach and that of ISO 26000:

RA1MSS,

RA2process approach,

RA3certication.

In other words, we want to understand what are

the views of the standard developers in terms of

MSS, process approach and certication. In parti-

cular, who supports/dismisses these approaches and

why as well as what alternatives are available. Our

overall aim is to explore this area and provide an in-

depth picture of the views surrounding this matter.

4.1. Sample

Our sample consists of ISO member body

delegations, invited international groups and orga-

nisations at the ISO International Conference on

Social Responsibility. The conference took place in

Stockholm, Sweden, on June 2004. It drew together

355 participants from 66 countries, including 33

developing countries, representing the following

stakeholder groups:

national standards bodies,

industry,

government,

labour,

consumers,

ARTICLE IN PRESS

P. Castka, M.A. Balzarova / Int. J. Production Economics 113 (2008) 7487 79

international and nongovernmental organisa-

tions (NGOs).

4.2. Data gathering

The conference consisted of plenary sessions,

stakeholder presentations, panel discussions and

parallel breakout sessions. The rst two (plenary

session and stakeholder presentations) consisted of

presentations from the Advisory Group on Social

Responsibility members and invited speakers, while

the remaining two were made up of round-table

discussions. We tape-recorded all presentations and

discussions, which were then transcribed verbatim.

We did not take part in the discussions, allowing the

participants to express their views openly. Our

approach was to analyse what was said, rather than

force the discussion or use of other means, such as

individual interviews, to collect additional data.

This would undoubtedly strengthen our research

design, yet it was physically and politically impos-

sible.

4.3. Data analysis

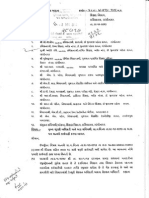

For the purposes of data analysis, we have used

the coding system depicted in Fig. 1. We had three

high-level codes that corresponded to the main

research areas (RAs 13; discussed previously).

Secondly, for each cluster, we used a second tier

of codes that consisted of stakeholder group,

stakeholder position and stakeholder rationale

(all described in Fig. 1).

At the rst stage of data analysis, we reviewed the

whole transcript and selected the data that were

applicable to this research (i.e. statements from the

participants related specically to issues in RA 13).

Consequently, we worked independently from each

other and used the high-level codes to cluster the

data. Afterwards, we came together and compared

our results. We followed the advice of Miles and

Huberman (1994) as well as Druskat and Wheeler

(2003) to assess the inter-rater reliability, i.e. a

number of agreements divided by the sum of the

total number of agreements and disagreements. The

initial result was 0.91, which exceeded the minimal

level set by Miles and Huberman (1994). We

concluded that this was because (a) the coding

scheme was set at a high level (we had only three

coding clusters as described above); (b) we are both

experienced coders; and (c) we have both prior

experience in this area and therefore were able to

understand the jargon used by the participants. We

have furthermore decided to resolve the discrepan-

cies.

After this initial clustering, we coded the in-

formation using the second tier of codes (see Fig. 1).

We used an identical coding system for all clusters.

For instance, the statement I fully agree with [the

previous speaker] about PDCA [Plan Do-Check

Act]. It has the operational element companies

want by a participant from industry was coded as

[Stakeholder groupindustry], [Stakeholder posi-

tionagreement], and the statement it has the

operational element companies want was coded as

[Stakeholder rationalejustication].

At this stage of the data analysis, we also

discussed the possibility of introducing a more

detailed coding system. This idea was however

dismissed. The discussions (hence the data) ap-

peared to be rather generic without needing a great

level of detailed analysis. In general, participants

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Management

System Standards

Certification Process Approach

Stakeholder groups

Stakeholder position

(agreement vs. disagreement)

Stakeholder rationale

(justification of stakeholders

position)

national standard bodies

industry

government

labour

consumers

international and nongovernmental

organisations (NGOs)

Fig. 1. Coding system for the study.

P. Castka, M.A. Balzarova / Int. J. Production Economics 113 (2008) 7487 80

expressed their agreement or disagreement with the

issue of MSS, process approach and certication, as

well as provided a short explanation (see example

above). Here our coding system proved sufcient. In

some cases, however, we were not able to use the

very element in our coding system. For instance,

discussions based around certication in many cases

brought statements such as certication would not

bring any value without either rationale behind the

statement or justication. However, this was in line

with our expectation that the process of ISO 26000

development is in its infancy and also that it would

be politically driven. Hence at this stage, standard

developers would focus predominantly at clarica-

tion of their positions and general views. In Table 2,

we present extracts from the data to illustrate the

nature of the data. In the following sections, we

present the results of this study.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Table 2

Excepts from the data

Management systems

standard

The advisory group recommends guidance not a specication document against which the conformity can

be assessedyy. The background, the discussion of this topic was that classical management system

approach not promotedyenhancing credibility that is the area where ISO can add valuey. ISO guidance

document must be more than addressing management systems standard, it should give the practical

guidance on diversity of issues and how to handle them, business needs (small and medium, different sizes),

national regulations.

AG Member, ISO Advisory Group on Social Responsibility

I like very much the concept of SA 8000 standard, which uses the concept of conventions and that is the

correct one for the companies. And I think that is a good approach because at the one hand it fulls the

recommendation of the report that the existing laws are not changed and are taken as they are, and make

the requirements for the companies.

Participant, Plenary

ya management system framework is not agreeable.

Participant, NGO

I heart my colleague that he is seeking the certiable standard in order to supersede SA 8000 and its

requirements with the presumption that ISO has a powerful enough brand to supersede these other

requirements. That is the question to answer whether ISO has the powerful enough brand. And whether it

will just become another requirement.

Participant; Industry session

I do not agree with ICC what they said yesterday and I do not agree with SIEMENS. Yes it will be difcult

and yes it is a complex area. If ISO will not do it, we will have others who will produce international,

national, local difcult initiatives that will all make this area and make it more difcult to move around.

ISO needs to take this forward not just as a guidance document but also as a standard documenty.

Denitely the standard, we need to take discussions.

Participant, Plenary

I fully agree with [the previous speaker] about PDCA. It has the operational element companies want.

Maybe multinationals do not want the standardy. it is a well-known methody. we need to give

[companies] a tool to prioritize because companies cannot address these issues at the same time.

Participant; Industry session

Process approach Over last 2 years we have benchmarked many standards, Australian, Spain, Japan, Mexico; if go to

AA1000 or SA 8000, what is the main component? PDCA.

Participant; Industry session

As we discussed in the AG, this PDCA method smells much too much as a future management system

standard, this is not the way to tackle CSR. CSR needs some better tools, some better guidance than a

classical management system standard. This is why the recommendations say this is not the subject to

guidance document.

AG Member; ISO Advisory Group on Social Responsibility

Certication There is a very strong concern within the NGO community that ISO document will become the alibi

document to use the standard for advertising purposes and that is the reason why we want to have a

standard that contains ethical requirements and not the management system standard. A management

system standard would be hardly agreeable with the NGO.

Participant, NGO

P. Castka, M.A. Balzarova / Int. J. Production Economics 113 (2008) 7487 81

5. Results

5.1. Management systems standard (MSS)

The topic of the MSS approach, as a basis for the

social responsibility standard, became a leitmotif

throughout the entire conference. Overall, our data

shows that the participants were polarised into two

groups. There were those who favoured the MSS

approach and those who opposed it. This polarisa-

tion was predominantly inuenced by (a) a personal

stance towards meta-standards, (b) belonging to a

particular stakeholder group and (c) demography-

developed versus developing countries.

Advocates (including past ISO 9000 and ISO

14000 developers, consultants, company representa-

tives, etc.) pointed to the benets that companies

obtain from ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 certication

such as improved performance, acquiring of

best practices or improved communication in

the supply chain. Furthermore, ISO 9000 was

presented as an established platform that could

contribute to the dissemination of, and learning

about, social responsibility standard as well. The

opponents representing NGOs, Labour and some

Industry, especially large multinational corpora-

tions, strongly dismissed the idea of MSS. Industry

representatives argued that an MSS is not necessary

because the industry has their own solutions to deal

with social responsibility and ethical issues. Further-

more, it was mentioned that ISO 9000 often does

not full the internal requirements of multinational

corporations, and yet another standard would

only increase the cost with little impact on

improvement of social responsibility in organisa-

tions. In case of NGOs and Labour participants,

they were against an MSStheir alternative being a

guidance document.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Table 2 (continued )

You cannot have any system without some kind of process of verication. However, I think that the

problem with the certication has been, that it is one process of verication and there many different

processes of verication that are dependant upon who is relying on claims; and the size of the organisation

and the purpose of making the claims, so I think that one of the benets of the document or standard

document might be to set out alternative methods of verication so that they match the organisation and so

they match the intent, of what the claim is being used for and who is being relying it upon.

Participant, Others

I think to set a standard for this matter would be a huge mistake. Because what is a standard? We put a

standard in place in order to prevent people from doing things that should not have been done or to give the

guidance how they should do things they do not know. Now, in this subject matter, we need to give

guidance to different corporation how to be leaders in this world by giving example of leadership to other

corporation, suppliers, environment, to the public.

Participant, Motorola

yCertication would not bring any value for the company and its suppliers and that they would only put

millions into certication.

Participant, siemens

I know that there might be a cost [for certication] that customers will have to pay but they are also paying

$200mil nes for doing bad marketing. So we need to discuss what is ethical pay and what is SR for

organisations not just companies. And also take into consideration countries where governments dont

have the same strengths and same resources for doing this. We need to be fair as organisations. We need to

help each other to move this forward because it is our responsibility.

Participant, Industry

The key question is how to make it credible. And I am afraid that there are no options available than to go

for 3rd party certication.

Participant, Industry

I fundamentally disagree with the notion of guidance document being satisfactory. Regardless of whether

or not the certication has been done up to date, there are ways to verication [agrees with previous

speaker] to getting this credibility, perhaps better than it exists.

Participant, National Standards Body

Note: Language in the quotes was not corrected; PDCA Plan Do Check Act; NGO non-governmental organisations; AG Advisory

Group; CSR Corporate Social Responsibility.

P. Castka, M.A. Balzarova / Int. J. Production Economics 113 (2008) 7487 82

Participants from developing countries showed

considerable agreement on the benet of having an

international standard for social responsibility.

Some of these explicitly pointed out that an MSS

would be preferable. The major argument was that

many CSR standards are imposed on suppliers

from developing countries. These organisations

have to comply with them and that is a prerequisite

for these organisations to enter some markets and

networks. Here, as one participant said, it would

be better to have one leader [ISO] than hundreds of

different schemes. Furthermore, participants from

developing countries emphasised the need to involve

their representatives in the ISO 26000 development

process. They typically stated that with ISO

developing countries can at least inuence the

standard.

The participants showed disunity over the funda-

mental approach to standardisation of social

responsibility. Some were in favour of guidance

standard, while others were in favour of manage-

ment systems standard. Whilst the plenary was asked

to indicate by vote who was in favour of these

approaches, the result was a 50:50 split.

5.2. Process approach

Process approach is one of the eight quality

principles (ISO 9004) and a fundamental building

block of ISO 9000/ISO 14000. Therefore, it was

another key theme of the discussions. Similar to the

discussions around the suitability of the MSS

approach, the participants remained divided in their

opinions.

Firstly, it was argued by the member of the

Advisory Group on Social Responsibility that the

process approach is not suitable for social respon-

sibility standardisation:

ISO must focus on results. Not on process. ISO

14000 is a processit does not work with social

responsibility. That is why we are talking about

the guidance documenty [we need to] provide

practical methods and guidance for operationa-

lizing SR, fullling the expectations of the

society, identifying and engagement with stake-

holders.

Even though many participants acknowledged

that the process approach does not a priori ensure

results, they also pointed out possible drawbacks

embedded in the results approach such as introdu-

cing uniformity of views on social responsibility,

the danger of ignoring local differences, forcing

the focus on results instead of on improvement.

Furthermore, many of these drawbacks were closely

discussed in relation to the differences in regulatory

systems, which limited the success of reinforcement

of international law in many countries and the

legitimacy of ISOs social responsibility standard. It

was generally acknowledged that these were clearly

the forces constraining, and signicantly affecting,

the design of the social responsibility standard.

Secondly, the PDCA approach, mostly used by

quality practitioners and advocated by leading

quality experts, is a critical mechanism in ISO

9000 and ISO 14000, became another controversial

topic in the discussion. Here again, it was the

dismissive position of the Advisory Group on Social

Responsibility towards the PDCA that triggered the

debate. Many participants expressed their support

for the PDCA approach explicitly. They had two

common arguments: (a) it is a well-established

mechanism to learn and (b) many national and

other standards employed this approach. The

former argument was that PDCA has the opera-

tional elements that companies want, it is a well

known method and we need to give companies

the tool to prioritise because they cannot address

these issues at the same time. The latter arguments

linked the PDCA to other standards like SA8000,

AA1000 or national initiatives/standards in coun-

tries such as Australia, Spain, Japan, Mexico.

5.3. Certication

The issue of certication came across hand in

hand with the discussion on the feasibility of an

MSS and experience with the ISO 9000/ISO 14000

certication. Here, the credibility of certication

was often questioned and many participants com-

mented sarcastically about the verication indus-

try or a small number of consultants having jobs

out of that. The following themes, underlying most

of the arguments, are addressed below.

Firstly, some participants expressed a fear

about a possible misuse of certication. Especially,

NGOs and labour participants were very vocal in

dismissing the idea of certication, which they felt

could become an alibi document for advertising

purposes rather than a real commitment to social

responsibility. At the other side of the spectrum,

some industry participants pointed out that if

some activist groups start to mandate that you

can sell and must have a SR standard on this or that

ARTICLE IN PRESS

P. Castka, M.A. Balzarova / Int. J. Production Economics 113 (2008) 7487 83

market, it will become quasi-mandatory to do a

business.

Secondly, it was often reported that the nature of

MSS drives the behaviour towards compliance

with minimal requirements rather than seeking

improvements or encouraging a genuine effort into

improvement-related activities. Many participants

strongly asserted that social responsibility standar-

disation should be voluntary and based on leading

by example, not by imposing rules and require-

ments:

y to set a standard in this matter would be a

huge mistakey leadership is never imposed.

Leadership is earned and therefore we should not

do the standard and [force] corporations to be

the leaders of so and so. The right way is to let

corporations earn the leadership. The right way

is to give an opportunity to guide smaller

organisation and public in order to get the right

results. We should provide the guidance for

organisations to be leaders in the world.

Many participants were pointing out that if there

are no requirements in ISO 26000, it would be very

difcult to judge organisations commitment to

social responsibility and ISO 26000. As one

participant put it:

it is a risk for ISO itself and its reputation if

organisations will claim that they follow ISO

guidance. We will not know because of the

missing requirements.

However, the representatives of multinationals

pointed out that ISO 9000/ISO 14000 requirements

are often not sufcient for their business and that

their corporations require more from their suppli-

ers. They also stressed that certication would not

bring any value for the company nor the suppliers,

and would just put millions into the certication

industryincreasing the cost for their customers

and suppliers.

However, other participants, even though ac-

knowledging that the certication process was not

fully satisfactory thus far, probed further discussion

into how to improve the certication process and, in

fact, redesigning it in order to suit the changing

societal needs. Firstly, it was mentioned that ISO

should come with alternative methods of verica-

tionto match different needs of various organisa-

tions. Here participants mentioned, for instance,

that social responsibility intensity in various in-

dustries differswith some organisations and some

industry sectors having rarely problems with ethical

issues and others having those more often (see also

the quote in Table 2). Secondly, it was suggested

several times that ISO can establish a web-site

listing organisations following the standard and

their resultsa proposition favoured by some and

regarded as not sufcient by others.

6. Discussion

Through this study we have conrmed that the

standard development agenda in its initial stages has

been driven by politics and the participants have

shown contradictory views based on their personal

interests and beliefs. At the same time, the study

provided a rich picture of the views of standard

developers on the divergence from a meta-standard

towards a guidance standard. The study also

highlighted the impact of ISO 9000 and ISO 14000

on the development of ISO 26000.

Our rst conclusion from this study is that

standard developers have polarised opinions over

the nature of the future social responsibility

standard. Our research shows that despite the

existence of ISO 26000 development primary as a

guidance standard, there is a large percentage of

standard developers who strongly advocated a

management systems approach and third-party

certication, which would be similar to ISO 9000

and ISO 14000. What should also be noticeable is

the disparity of views of different stakeholder

groups on these issues; as shown, there was a strong

opposition from the labour and NGO stake-

holder group, as well as a division of opinions

amongst industry stakeholders. However, third-

party certication was almost unanimously seen as a

problematic areano matter whether participants

supported certication or not. Proponents of

certication typically argued that there was no

better way whilst the opponents dismissed certica-

tion pointing at disfunctionality, malpractice and

disreputable practices in the certication industry.

Overall, the disagreement of standard developers

over the issue of third-party certication is probably

one of the major forces towards a different direction

for standardisation of social responsibility.

Our second conclusion was that the shift toward a

guidance standard (as opposed to MSS) was largely

a politically driven decision. The direction set by the

Advisory Group on Social Responsibility was to

develop a guidance standard, and therefore not a

specication standard against which conformity

ARTICLE IN PRESS

P. Castka, M.A. Balzarova / Int. J. Production Economics 113 (2008) 7487 84

could be assessed. This has been maintained even

though a large percentage of standard developers

expressed different points of view. From this we

conclude that the decision to develop a guidance

standard rather seems to be a platform for a

consensus of involved parties and not necessarily a

directive to develop a substantial standard for social

responsibility. As shown, politics played a signi-

cant role in the early stages of ISO 26000 develop-

ment. Here, our conclusion is echoed by Bowers

(2006):

The International Labor Organization (ILO) is

participating, but only under the security of its

memorandum of understanding [effectively giv-

ing ILO veto power over labor related sections in

the standard]. The Global Reporting Initiative

(GRI), a privately organized and funded NGO

that develops standards, is participating, but

certainly in part to protect its own interests.

Other NGOs and consumers who are participat-

ing would prefer a mandatory minimum stan-

dard that could be more demanding than a

national labor or environmental standard. Gov-

ernments, to the limited extent they are partici-

pating, are either protecting their turf or seeking

powers they do not have statutorily or nan-

cially.

Our nal conclusion from this research study is a

call for future research in the arena of ISO

management standards. Some of the arguments

and opinions of standard developers that were used

to inuence the development of ISO 26000 deserve

attention and empirical investigation. In particular,

the arguments over the malpractice in third-party

certication and inefciencies of ISO management

systems standards in general require further inquiry.

Our experience, from working with practitioners

and professional bodies in quality in several

countries and with the ISO community, conrms

the somewhat negative attitude amongst practi-

tioners towards ISO management system standards

and third-party certication. However, apart from

this anecdotal evidence, we have not found any

empirical study that has credibly dealt with these

issues.

7. Limitations of the research

There are some limitations to our research that

we would like to acknowledge. This research is

limited to the investigation of the impact of ISO

9000 and ISO 14000 on the development of social

responsibility standard. Hence, other topics that are

closely related (such the role of governments, the

role of legislation, legislative enforcement in devel-

oping countries, alignment with ILO Conventions)

are outside the scope of this paper. Furthermore, it

should be noticed that the data collected in this

research were focused largely at the high-level

issues, such as the feasibility of an MSS or

credibility of certication. The research at this stage

did not allow for deeper inquiry into further

explanations. Hence this research should be seen

as a reection of the rst stages in the development

of social responsibility standards and as a basis for

future investigations.

Further limitation of this research is in the choice

of the participants for our study. This study

provides an inside perspective on the standard

development and includes its direct participants.

The study, therefore, relies on the appropriateness

of the nomination process of the ISO, and hence

inevitably has its limitation. For instance, some

countries choose not to get involved, some stake-

holder groups can be under-represented (Hallstrom,

2000) and the whole process of standardisation is

inuenced by self-interest of standard developers

and their respective stakeholder groups (Bowers,

2006; Hallstrom, 2000; Seddon, 2000). Nevertheless,

our research aimed to investigate those views, so it

may only be appropriate for the purpose of this

study.

8. Future research

The introduction of ISO 26000 will inevitably

bring fruitful ground for future research. Amidst the

plethora of options, we would like to highlight and

recommend several areas. Firstly, studies into

diffusion patterns of ISO 26000, which determine

why, under what circumstances and which organi-

sations and supply chains adopt ISO 26000, will

shed more light on the role of ISO 26000 in the

pursuit of the SR agenda. Here, the work on

diffusion of ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 (i.e. Corbett,

2006) and rst predictions on the diffusion of ISO

26000 (Castka and Balzarova, 2007) can serve as

useful starting points. Secondly, since ISO 26000

will not be certiable, evaluations of claims made in

relation to ISO 26000 will also be necessary. Here

researchers can initially focus on the theoretical

developments and debates (before the introduction

of ISO 26000) and later on the evaluation of the

ARTICLE IN PRESS

P. Castka, M.A. Balzarova / Int. J. Production Economics 113 (2008) 7487 85

claims organisations will make in relation to ISO

26000. Thirdly, recent debates within ISO suggest

that there is a willingness in ISO to tighten

certication and accreditation practices (Wade,

2002; Lal, 2004). The International Accreditation

Forum and ISO stepped forward to address the

criticism by revisions of the requirements for

accreditation bodies, who accredit conformity, and

for auditor competences (Feary, 2005). Future

studies can focus on analysis and evaluation of

these activities to determine whether this can bring

ISO 26000 towards third-party certication.

9. Conclusion

ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 signicantly inuenced

the rst steps in standardisation of social responsi-

bility. Indeed, the global diffusion of both of these

standards and its meta-standard approach to

standardisation of management practice gave the

initiators of social responsibility standardisation an

approach to grasp the social responsibility agenda

(ISO/Bulletin, 2002). This is true not only for

national standards such as DR03028 (2003) and

SII10000 (2001), but also for standards such as

SA8000 (2001) and AA1000 (1999). SA8000 was

designed as an auditable standard for a third-party

verication system and AA1000 is an accountability

standard, focused on securing the quality of social

and ethical accounting, auditing and reporting.

Both of these are built around notions of policies,

audits, management reviews and continuous im-

provement, which are typical elements of ISO 9000

and ISO 14000.

ISO 26000 avoided third-party certication, yet

this can cause problems and raise further questions.

Research shows that guidance documents are often

widely unknown and their purpose is unclear (Boys

et al., 2004). The risk here is that a guidance

document, without a clear purpose and question-

able credibility, can hamper the adoption and

diffusion process of ISO 26000. Indeed, third-party

certication can provide at least some level of

condence even if it is perceived as having eroded

credibility. Hence ISO 26000 will have to nd other

ways to insure that the standard is not misused. One

of the ways would be to use the approach of UN

Global Compact and require companies to disclose

information about the ways it supports ISO 26000

and its principles. Other approaches can encompass

different certication schemes tailored to the type of

claims that the organisation makes. Developments

in these areas are necessary for ISO 26000 to add

value to the uptake of the social responsibility

agenda.

References

AA1000, 1999. AA 1000 Standard, AccountAbilityInstitute of

Social and Ethical Accountability, London.

Aarts, F.M., Vos, E., 2001. The impact of ISO registration on

New Zealand rms performance: A nancial perspective. The

TQM Magazine 13, 180.

Abraham, M., Crawford, J., Carter, D., Mazotta, F., 2000.

Management decisions for effective ISO 9000 accreditation.

Management Decision 38, 182.

Ahmed, P.K., Machold, S., 2004. The quality and ethics

connection: Toward virtuous organizations. Total Quality

Management & Business Excellence 15, 527.

Balzarova, M., Castka, P., Bamber, C., Sharp, J., 2006. How

organisational culture impacts on the implementation of ISO

14001:1996a UK multiple-case view. Journal of Manufac-

turing Technology Management 17, 89.

Boys, K., Karapetrovic, S., Wilcock, A., 2004. Is ISO 9004 a path

to business excellence? Opinion of Canadian standards

experts. The International Journal of Quality & Reliability

Management 21, 841.

Bowers, D., 2006. Making social responsibility the standard.

Quality Progress 39, 35.

Briscoe, J.A., Fawcett, S.E., Todd, R.H., 2005. The implementa-

tion and impact of ISO 9000 among small manufacturing

enterprises. Journal of Small Business Management 43, 309.

Brunsson, N., Jacobsson, B., 2000. The contemporary expansion

of standardization. In: Brunsson, Jacobsson (Eds.), A World

of Standards. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 117.

BS5750, 1987. Quality Systems. British Standards Institution,

London.

Casadesu s, M., Karapetrovic, S., 2005. The erosion of ISO 9000

benets: A temporal study. The International Journal of

Quality & Reliability Management 22, 120.

Castka, P., Balzarova, M., 2007. ISO 26000 and supply chains

on the diffusion of the social responsibility standard and

practices. International Journal of Production Economics,

doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2006.10.017.

Castka, P., Bamber, C., Bamber, D., Sharp, J.M., 2004a.

Integrating corporate social responsibility (CSR) into ISO

management systemsin search of a feasible CSR manage-

ment system framework. The TQM Magazine 16, 216.

Castka, P., Bamber, C., Sharp, J.M., 2004b. Implementing

Effective Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate

GovernanceA Framework. British Standards Institution,

London.

Castka, P., Balzarova, M., Bamber, C., Sharp, J., 2004c. How

can SMEs effectively implement the CSR agendaa UK case

study perspective. Corporate Social Responsibility and

Environmental Management 11, 140.

Corbett, C.J., 2006. Global diffusion of ISO 9000 certication

through supply chains. Manufacturing and Services Opera-

tions Management 8, 330.

Corbett, C.J., Kirsch, D.A., 2001. International diffusion of ISO

14000 certication. Production and Operations Management

10, 327.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

P. Castka, M.A. Balzarova / Int. J. Production Economics 113 (2008) 7487 86

Corbett, C.J., Klassen, R.D., 2006. Extending the horizons:

Environmental excellence as key to improving operations.

Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 8, 5.

Corbett, C.J., Montes-Sancho, M.J., Kirsch, D.A., 2005. The

nancial impact of ISO 9000 certication in the United States:

An empirical analysis. Management Science 51, 10461059.

Dalgleish, S., 2005. ISO 9001 proves ineffective. Quality 44, 16.

DR03028, 2003. Corporate Social Responsibility-Draft Austra-

lian Standard, Committee MB-004. Standards Australia,

Sydney.

Druskat, V.U., Wheeler, J.V., 2003. Managing from the

boundary: The effective leadership of self-managing work

teams. Academy of Management Journal 46, 435.

Feary, S., 2005. Effective accreditation is essential for audit

competence. ISO Management Systems 5, 1822.

Guler, I., Guillen, M.F., Macpherson, J.M., 2002. Global

competition, institutions, and the diffusion of organizational

practices: The international spread of ISO 9000 quality

certicates. Administrative Science Quarterly 47, 207.

Hallstrom, T.K., 2000. Organizing the process of standardiza-

tion. In: Brunsson, Jacobsson (Eds.), A World of Standards.

Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 8599.

Hallstrom, T.K., 2004. Organizing International Standardiza-

tion. ISO and IASC in Quest of Authority. Edward Elgar,

Cheltenham.

ISO/AG/SR, 2004a. Working Report on Social Responsibility.

ISO Advisory Group on Social Responsibility, International

Organization for Standardization, Geneva.

ISO/AG/SR, 2004b. Recommendations to the ISO Technical

Management Board, Document: ISO/TMB AG CSR N32.

International Organization for Standardization, Geneva.

ISO/Bulletin, 2002. A Daunting New ChallengeAre Standards

the Right Mechanism to Advance Corporate Social Respon-

sibility. ISO Bulletin.

ISO COPOLCO, 2002. The desirability and feasibility of ISO

Corporate Social Responsibility Standards. Final Report by

the Consumer Protection in the Global Market Working

Group of the ISO Consumer Policy Committee (COPOLCO),

May 2002. International Organization for Standardization,

Geneva.

ISO/Survey, 2004. The ISO Survey of ISO 9000 and ISO 14000

Certicates. Fourteens cycle: up to and including 31

December 2004. International Organization for Standardiza-

tion, Geneva.

ISO/TMB/WG SR N49, 2005. ISO Guidance Standard on Social

ResponsibilityISO 26000, ISO/TMB/WG SR. International

Organization for Standardization, Geneva.

Kartha, C.P., 2002. ISO9000: 2000 quality management systems

standards: TQM focus in the new revision. Journal of

American Academy of Business, Cambridge 2, 1.

Lal, H., 2004. Re-engineering the ISO 9001:2000 certication

process. ISO Management Systems 4, 15.

Laszlo, G.P., 2000. ISO 90002000 version: Implications for

applicants and examiners. The TQM Magazine 12, 336.

Lockett, A., Moon, J., Visser, W., 2006. Corporate social

responsibility in management research: Focus, nature,

salience and sources of inuence. Journal of Management

Studies 43, 115136.

Martinez-Costa, M., Martinez-Lorente, A.R., 2003. Effects of

ISO 9000 certication on rms performance: A vision from

the market. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence

14, 1179.

Miles, M.B., Huberman, A.M., 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis.

Sage, London.

Naveh, E., Marcus, A., Moon, H.K., 2004. Implementing ISO

9000: Performance improvement by rst or second

movers. International Journal of Production Research 42,

18431863.

Neumayer, E., Perkins, R., 2005. Uneven geographies of

organizational practice: Explaining the cross-national

transfer and diffusion of ISO 9000. Economic Geography

81, 237.

Peddle, R., Rosam, I., 2004. Finding the balance. Quality World,

1826.

Poksinska, B., Dahlgaard, J.J., Eklund, J.A.E., 2003. Implement-

ing ISO 14000 in Sweden: Motives, benets and comparisons

with ISO 9000. The International Journal of Quality &

Reliability Management 20, 585.

Rosam, I., Peddle, R., 2004. Implementing Effective Corporate

Social Responsibility and Corporate GovernanceA Guide.

British Standards Institution, London.

SA8000, 2001. Social Accountability. Social Accountability

International, London.

Seddon, J., 2000. The Case Against ISO 9000. Oak Tree Press,

Dublin.

Sharma, D.S., 2005. The association between ISO 9000 certica-

tion and nancial performance. The International Journal of

Accounting 40, 151.

SII10000, 2001. Social Responsibility and Community Involve-

ment. Draft Standard. Standards Institution Israel, Tel Aviv.

Struebing, L., 1997. Changes to ISO 9000 in the year 2000.

Quality Progress 30, 19.

Takakusa, H., 2005. Fast forwardJapanese perspective on ISO

9001 advocates implementation knowledge-sharing. ISO

Management Systems 5, 30.

Terlaak, A.K., 2002. Exploring the adoption process and

performance consequences of industry management stan-

dards: The case of ISO 9000. Ph.D. Thesis, University of

California, Santa Barbara.

Uzumeri, M.V., 1987. ISO 9000 and other metastandards:

Principles for management practice? The Academy of

Management Executive 11, 21.

van der Wiele, T., Iwaarden, J.V., Williams, R., Dale, B., 2005.

Perceptions about the ISO 9000 (2000) quality system

standard revision and its value: The Dutch experience. The

International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management

22, 101.

Waddock, S., Bodwell, C., 2004. Managing responsibility: What

can be learned from the quality movement? California

Management Review 47, 25.

Wade, J., 2002. Is ISO 9000 really a standard? ISO Management

Systems 2, 127.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

P. Castka, M.A. Balzarova / Int. J. Production Economics 113 (2008) 7487 87

You might also like

- Iso 26000Document2 pagesIso 26000ToanNguyen100% (1)

- Determinants of CSR Standards Adoption: Exploring The Case of ISO 26000 and The CSR Performance Ladder in The NetherlandsDocument22 pagesDeterminants of CSR Standards Adoption: Exploring The Case of ISO 26000 and The CSR Performance Ladder in The NetherlandsYamashitaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Quality Management Systems OnDocument5 pagesImpact of Quality Management Systems OnRegalado SheilaNo ratings yet

- ISO 26000 Among Other ISO Standards: Przedsiebiorczosc I Zarzadzanie. Entrepreneurship and Management October 2018Document17 pagesISO 26000 Among Other ISO Standards: Przedsiebiorczosc I Zarzadzanie. Entrepreneurship and Management October 2018Azizah Wani TanjungNo ratings yet

- ISO 26000 - A Standardized View on Corporate Social Responsibility: Practices, Cases and ControversiesFrom EverandISO 26000 - A Standardized View on Corporate Social Responsibility: Practices, Cases and ControversiesNo ratings yet

- ISO 14000 Standards - IntroductionDocument2 pagesISO 14000 Standards - IntroductionDexter John Gomez JomocNo ratings yet

- Guidance ISO 26000 CSR Versi INDDocument3 pagesGuidance ISO 26000 CSR Versi INDGuntur Ekadamba Adiwinata0% (1)

- Iso26000 PDFDocument5 pagesIso26000 PDFAsfa JaVedNo ratings yet

- ISO 26000 For Corporate Social Responsibility How To Get StartedDocument14 pagesISO 26000 For Corporate Social Responsibility How To Get StartedH Kurniawan K100% (2)

- Iso 26000Document17 pagesIso 26000Shikha PopliNo ratings yet

- ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 Towards A ResearcDocument19 pagesISO 9001 and ISO 14001 Towards A ResearcMiren Heras SánchezNo ratings yet

- CSR - Iso-26000Document14 pagesCSR - Iso-26000Adelson AradoNo ratings yet

- Discussion On ISO 26.000Document8 pagesDiscussion On ISO 26.000Marcelo MonteverdeNo ratings yet

- International Standard Organization 26000.docx - RecoveredDocument31 pagesInternational Standard Organization 26000.docx - RecoveredMandira PriyaNo ratings yet

- CSR and Total QualityDocument10 pagesCSR and Total QualityUmerNo ratings yet

- ISO 9001 Guide for Quality Management SystemsDocument8 pagesISO 9001 Guide for Quality Management SystemshariNo ratings yet

- The New Management System ISO 21001:2018: What and Why Educational Organizations Should Adopt ItDocument9 pagesThe New Management System ISO 21001:2018: What and Why Educational Organizations Should Adopt IttarrteaNo ratings yet

- ISO 26000 Social ResponsibilityDocument4 pagesISO 26000 Social ResponsibilityStakeholders360No ratings yet

- ISO 26000 - Social ResponsibilityDocument5 pagesISO 26000 - Social ResponsibilityGihan TalgodapitiyaNo ratings yet

- Iso 14000 Series of Standards by Cynthia MartincicDocument9 pagesIso 14000 Series of Standards by Cynthia MartincicJohn Lloyd JuanoNo ratings yet

- Unit 9 RMDocument7 pagesUnit 9 RMMariaNo ratings yet

- Setting international HR standardsDocument7 pagesSetting international HR standardsNoha_Moustafa59No ratings yet

- A Review of The Impact of ISO 9000 and ISO 14001 Certifications - LERDocument10 pagesA Review of The Impact of ISO 9000 and ISO 14001 Certifications - LERAderlanio CardosoNo ratings yet

- Iso 9001 and The Field of Higher Education Proposal For An Update of The Iwa 2 Guidelines PDFDocument6 pagesIso 9001 and The Field of Higher Education Proposal For An Update of The Iwa 2 Guidelines PDFYunusNo ratings yet

- Applic ISO 14000Document79 pagesApplic ISO 14000danni1No ratings yet

- ISO 9001 Quality Management Systems through the lens of Organizational CultureDocument7 pagesISO 9001 Quality Management Systems through the lens of Organizational CulturePaulderdice CostaNo ratings yet

- ISO 26000 Guide on Social ResponsibilityDocument16 pagesISO 26000 Guide on Social Responsibilityochadew100% (2)

- ISO 26000 Guidance ExplainedDocument54 pagesISO 26000 Guidance ExplainedPrakhar GuptaNo ratings yet

- ISO 9000 - 2000 Digs Own Grave PDFDocument4 pagesISO 9000 - 2000 Digs Own Grave PDFVCNo ratings yet

- 18 - (2013) Heras-Saizarbitoria & Boiral - IsO 9001 and ISO 14001Document19 pages18 - (2013) Heras-Saizarbitoria & Boiral - IsO 9001 and ISO 14001Toño BalderasNo ratings yet

- IsO 9004 2000, Quality Management Systems - Guidelines For Performance ImprovementsDocument7 pagesIsO 9004 2000, Quality Management Systems - Guidelines For Performance Improvementschitti409No ratings yet

- Tqm-Iso 14000Document20 pagesTqm-Iso 14000kathirvelanandhNo ratings yet

- Anttila 2017Document17 pagesAnttila 2017Anass CherrafiNo ratings yet

- Iso 14000Document7 pagesIso 14000Sailaja Sankar SahooNo ratings yet

- Developing A Knowledge Management Policy For ISO 9001: 2015: John P. Wilson and Larry CampbellDocument17 pagesDeveloping A Knowledge Management Policy For ISO 9001: 2015: John P. Wilson and Larry Campbelljanrivai adimanNo ratings yet

- Iso 26000Document83 pagesIso 26000Miguel Carranza Cuesta100% (3)

- ISO 26000 Basic Training Material Annexslides 2017Document59 pagesISO 26000 Basic Training Material Annexslides 2017Averyl Lei Sta.Ana100% (2)

- Module 9 Iso 9000 Quality Management SystemDocument14 pagesModule 9 Iso 9000 Quality Management SystemCharlotte maeNo ratings yet

- Who We Are: What Is ISO?Document23 pagesWho We Are: What Is ISO?Anand AroraNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting The Implementation Effectiveness of ISO 9000Document13 pagesFactors Affecting The Implementation Effectiveness of ISO 9000Devesh UpadhyayaNo ratings yet

- ISO 9001 in Education SectorDocument4 pagesISO 9001 in Education Sectorpremala61No ratings yet

- Jurnal InternasionalDocument14 pagesJurnal InternasionalFadwa GhaidaNo ratings yet

- 3 Pecb - Seven Core Subjects Covered by Iso 26000Document4 pages3 Pecb - Seven Core Subjects Covered by Iso 26000Mary Joy OcampoNo ratings yet

- Josip Britvić, M.ADocument9 pagesJosip Britvić, M.ADennis LamNo ratings yet

- Effects of ISO 9000 Certification on ProfitabilityDocument7 pagesEffects of ISO 9000 Certification on ProfitabilityzahidNo ratings yet

- ISO DiscussionDocument8 pagesISO DiscussionAnonymous icKjy2agNo ratings yet

- ISO 26000 (2) Contents 2009-06Document21 pagesISO 26000 (2) Contents 2009-06guhatto100% (3)

- History of ISO 14000Document2 pagesHistory of ISO 14000Deblina Dutta0% (1)

- 10 1108 - MRR 02 2019 0054 2Document27 pages10 1108 - MRR 02 2019 0054 2Salma ChakrounNo ratings yet

- Topics in Lean Management ISO 900 ISO 14000Document45 pagesTopics in Lean Management ISO 900 ISO 14000Katrina Amore VinaraoNo ratings yet

- 2011-05-19 Ungc DS 49001Document16 pages2011-05-19 Ungc DS 49001Kim ChristiansenNo ratings yet

- Esearch Aper Eries: in Search of ISO: An Institutional Perspective On The Adoption of International Management StandardsDocument53 pagesEsearch Aper Eries: in Search of ISO: An Institutional Perspective On The Adoption of International Management Standardsazniwani83No ratings yet

- Guidance On - Auditing Climate Change Issues in ISO 9001Document10 pagesGuidance On - Auditing Climate Change Issues in ISO 9001GMNo ratings yet

- Iso - International Organization For StandardizationDocument15 pagesIso - International Organization For StandardizationRiyas ParakkattilNo ratings yet

- QualityDocument30 pagesQualityAdelina Burnescu50% (2)