Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Christoph Gantenbein2

Uploaded by

Häuser Trigo0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views5 pages'Typology transfer' is a design method, based on our understanding of architecture. 'Architecture and urbanism cannot be separated,' says Christoph Gantenbein.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document'Typology transfer' is a design method, based on our understanding of architecture. 'Architecture and urbanism cannot be separated,' says Christoph Gantenbein.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views5 pagesChristoph Gantenbein2

Uploaded by

Häuser Trigo'Typology transfer' is a design method, based on our understanding of architecture. 'Architecture and urbanism cannot be separated,' says Christoph Gantenbein.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

Architecture and Education | Interview 3

Christoph Gantenbein | January 2012

Samuel Penn: You practice in Basel with Emanuel Christ and run a unit at the ETH as assistant

Professors. The programme is called Typology Transfer, which examines the creation of new

architecture based on established types. I wonder whether you could explain what the motivation was

behind creating a programme like this?

Christoph Gantenbein: The Typology Transfer is a design method, based on our understanding of

architecture. And of course these two aspects cannot be separated. Let me first talk about

architecture, and then how we teach design. Architecture means to us primarily: urban typologies. So

far we have studied them in four cities Hong Kong, modern Rome, New York and Buenos Aires. We

focused on building types, not by simply portraying them but by analysing the buildings that are

relevant in terms of specificity and mass the building types out of which these cities are built. We try

to understand the city through its architecture. We absolutely believe, and this comes from our

practice, that architecture and urbanism cannot be separated. In our office when we look back over

the last thirteen years of our practice, we can clearly see that we are starting every design even of a

small house or building by the relationship it creates with its context. We always try to make urban

architecture. This is our belief, its not very new because Aldo Rossi was talking about similar things

that architecture is deeply linked into the city and that architecture itself is an expression of the urban.

This may be surprising, because you come from Scotland and perhaps expect a typically Swiss

position. There is of course another culture that isnt so close to us the Alpine understanding of the

nearly classicist object in the landscape. This is a different culture that we dont consider ourselves to

be part of. We focus on the city, and we think there is a huge crisis in the city. This might sound

strange, as theres an immense amount of research on the actual development of cities being done

by several architects, from Rem Koolhaas to Herzog & de Meuron at their ETH Studio Basel. We

think this analysis is very worthwhile, as it is necessary to be able to understand the city. But when it

comes to the level of creating the city through buildings, then we notice that architects are completely

lost. Based on this view of things, we developed a design method in our unit at the ETH where we

teach the students that a design of a building, that whatever you do as a creative individual, is linked

to an existing culture. We are convinced that the modernist idea of the architect as a genius is a lie.

This understanding of the architect claims the development of a design out of nothing but his own

imagination, and any outcome cannot really be understood by anyone except by himself. This idea

is a clich that has become attached to the architectural profession and we think that this is a

dangerous tendency we see that in this very misunderstood freedom lies a strong limitation to

creativity. Creating out of nothing doesnt lead to more freedom. I would say the opposite is true.

Complete freedom makes your inventions meaningless. But if you can deal with existing knowledge,

an existing culture of architecture, you can go much further. It was interesting in Hong Kong, you see

these buildings that are much more radical than the expressionist fantasies by Hermann Finsterlin or

by Hans Scharoun. The architecture is so fantastic in terms of how it sits in the landscape, its sheer

dimensions and also in its aesthetic. It doesnt mean to be radical and is in reality a very pragmatic

expression of conditions. Thats what we want to teach our students. Have a look at what exists. Try

to analyse it, to understand it, and try to understand the rules of its architecture, how its developed

and try to generate your own expressive project out of these rational rules.

SP: Id like to pick up on the the study of urbanism, which as you say broadly means the study of

context not just the physical but also the cultural context. There seem to be two ways to deal with

that approach. The pragmatic collection of data, and proposing that by collecting data we can

somehow derive what form should come from it. This is broadly an objective exercise. Then theres

the other way that Jacques Herzog, Pierre de Meuron, Marcel Meili and Roger Diener are pursuing at

Studio Basel that is an overall study of urban form in Switzerland and now other countries. The

conversations Ive had so far with both students and teachers at the institute in Basel pivot exactly on

the interesting point you made about the architect being lost. They can study urbanism, they can

study the context and all the data, they can compile it, bring it together, but then theyre lost when it

comes to the actual architecture. Thats a very interesting proposition and insight that you made. I

guess that your programme is somehow trying to bridge that gap, fill that void to mediate between

the realisation that architecture still depends on human judgement, and that there is therefore

creation, but that there is also a lost transmission, nothing we can instantly recognise as a tradition,

and so instead architects have to return to the cold, cool objects of the discipline or art, to somehow

find a language to develop their own voice within. Do you think thats a fair assessment or do you

think it might be a bit of a dystopian view of how we relate to history or how you and your practice

might relate to architecture?

CG: Thats exactly the point: The effect of conditions, described through facts and data on the one

hand and the architecture with its own autonomous rules on the other. This is the challenging

character of architecture, and we want to study it through examples that we generally find in

anonymous urban architecture. How architecture reacts to the climate, how it occupies the territory,

how it reacts to traffic or political development, all these conditions are recognisable in a building. On

the other hand, architecture has its own eternal rules. With this question in mind we created our

personal collection of facts and plans of these four cities. We studied the architecture of these

modern cities that are a result of urbanisation during and after industrialisation. We felt that historic

cities like Venice for instance wouldnt give us the answers to contemporary questions. It was both a

logical and intuitive decision to focus on modern cities intuitive inasmuch as we like the four cities

and have an immediate emotional connection to their architecture. For instance in Hong Kong we felt

the buildings were fantastic and in our guts that we wanted to understand how they came into being,

to figure out how the whole system worked. What we do with the typological research is very scientific

but also artistic at the same time. I dont think its possible to make architecture without an emotional

understanding of it, or without a comprehension of its culture. Our appreciation at this level comes

partly from our teachers. Hans Kollhoff opened our eyes to the wonders of the historic city and we

have transferred that enthusiasm to our analysis of modern cities. Cultivating an architectonic

sensibility is probably the most important aspect for an architect to develop in their working life and

its equally important that a teaching architect is able to pass on their grasp of architecture at that

level to their students. I think that might answer the first part of your question. The second part of your

question is about history.

SP: Yes, but rather than it being a scenographic approach to history, whereby motifs are sampled

and reused, I sense in your work that the relationship with history and the built form is deeper?

CG: Emanuel and I are atypically interested in history. After our diploma we both won a fellowship to

Italy to study Renaissance, Baroque and Rationalist architecture. I am also interested in the history of

politics that helps me personally to understand the relationship between architecture in a historico-

political context. Its almost impossible to understand architecture without gaining insights into the

social, economical and technological systems it was created in. Once you grasp these factors it is

easier to understand the other side of historic architecture which is what I eluded to before the

emotional. When you have studied Renaissance architecture and have seen it personally then you

start to get to know it, then you begin to feel the individual approaches of the figures that designed

them. When you visit the buildings of Michelangelo and Brunelleschi at San Lorenzo in Florence for

instance, you start to appreciate the different sensibilities of the architects and also the individual

forces and ideas that shape their work. I get an incredible sense of connection five hundred years

ago an individual was compelled to create a special work, of course they were in a particular context,

you have to know the context to be able to feel the individual part then you can get close to these

designers, they had the same love for material, for form, for proportion. One could say that we are

interested in this non-historic part of historic architecture.

SP: Whats interesting about your approach is that it is kind of anti art history?

CG: Yes. What makes us positively nervous is the notion of pure architecture. To be able understand

it in a pure way you have to abstract it from its historic and social context.

SP: The context in which these individuals worked and were taught was very different. They would

have been working in a specific milieu and I wonder whether they would have had the same

preoccupations with history as we do? Would they have been as intent on gathering or analysing

information as we are, or would they have strived toward a pure architecture and adjusted it to fit the

flow and ebb of the context they were working in. Im interested in this misconception that somehow

through gathering a lot of information, the building starts to shape itself, rather than using individual

genius or invention, a series of objective parameters determines the architecture. Do you think that

any of that information actually has an impact on what ends up being designed, or do you think that

there is a discipline of architecture, a canon of work so to speak, with particular lessons that give us

our understanding of what is appropriate to design. I think we should be honest about what we do and

instead of hiding behind veils of information.

CG: Of course: The knowledge of facts cannot automatically be translated into an architectonic or

urbanistic form. Architecture is not an automatic process of feeding facts and harvesting a form!

Thats why we think that the digital data and digital production opens a lot of possibilities but it is not

an interesting design method. It can create wonderful objects but for us this isnt relevant. So to be

able to design an object where I can bring in my abilities as a designer and my individual passions I

need to work with something that I find relevant. Working in the abstract makes us nervous and

Michelangelo was clear about this. In St. Peters and in the Palazzo Farnese he invented architecture

to re-establish the architectonic power of Rome that had become an unimportant city. He was in the

position to coin the future of that city. Where do we see this potential today? We feel at the moment

that there is a huge crisis in the city, that urbanity is a very undefined word, and that we have to

establish an idea of what urbanity can mean in this age. From our point of view it was so clear what it

meant in 19th century France, the bourgeois society, the avenue, these very formal spaces. Urbanity

has meant different things in different times and we just experience the complete absence of positive

ideas about the city today. Its a common idea that the modernist city is a model that is out of date

and is problematic, but nevertheless we hear a lot of criticism but no suggestion of a positive answer

to the real problems of the city. So when we collect the information we do in the cities we visit, which

is by the way not just the collection of statistics or data but real buildings. We then test these buildings

by using them in our own designs with the question of what they could contribute in the development

of a contemporary city. In this research there is somehow a simple idea that density is not just an

economical or ecological value but that it is mandatory in the creation of urbanity. We think that this

closeness of the activity of people is a conditio sine qua non for urbanity and that urbanity has to do

with real physical space and with people and that it is not affected by all the virtual social networks

of today that contemporary urbanity will happen in the public space of the city, but what we regard

to be public space is something that has to be developed and to be clarified. We believe that it could

be closer to the 19th century city. Hong Kong which was mainly built in the 60s and 70s has physical

and spatial qualities which have similarities to those of 19th century traditional European cities. So,

we need a clear idea of what we are looking for to be able to deploy our creative energy effectively.

SP: Its obvious that you are interested in 19th century urbanity because you tend to study cities that

display those tendencies politically. Hong Kong is an especially good example. The typical 19th

century city is a place of huge industrial expansion. It was at this point that architecture and planning

became professional disciplines it was also the point at which the profession had to start dealing

with risk and moved away from the previous position as artistic individuals to one of being public

servants and the sense of the medieval plot, or how a plot was developed changed radically. The

city expansion and the more medieval plot driven model are both quite easy to get to grips with.

When you go to Hong Kong there seems to be a bit of both. A tendency to get the most out of a plot

and the huge city extension plans. Its an incredible mix of vibrant planning ideologies. My question,

as always, is what the architects role is in all of this? Our role has shifted. In the 19th century

architects and engineers were still planning cities, in our contemporary context planning has become

a separate discipline, a defined body of knowledge (in the UK). Its difficult to place where our

responsibility now lies. It would seem that in reality the architect has a small part to play in the

creation of the city and that commercial forces determine the shape of the urban context. The

architect then works in a very confined space to get the most out of their plot. The expression of that

kind of city is just a selection of architectural exercises determined by the boundaries of a specific plot

and the regulations that impede upon it. I suspect that the planning of Hong Kong is not being

undertaken by architects. They are not thinking of what building would be best to reference on this

site or thinking what Michelangelo would do in this situation, and yet this situation creates what you

describe to be an incredibly dynamic urban form. Should we let go of the traditional notion of the

architect and become like ants unconsciously building ant-hills, or do we somehow still determine

within a discipline how we should live or do you think that this is no longer relevant?

CG: It is important that we as architects make proposals for the vision of our cities. I speak now as an

architect working in Switzerland where we have a very weak tradition of urban culture and the design

of cities. Thats why we look toward cities like Hong Kong, New York and Buenos Aires cities where

there was a huge economical pressure, established rules and a highly developed urban culture.

These are cities where the architect is almost unnecessary. In Buenos Aires you feel that the rules

are so clear that the buildings are authorless, without the hand of an architect. And its often those

designed without an architect that are the best. To compare those architects, or even constructers, to

ants, misses the point: They were professionals like us, working intelligently and hard and with a lot of

skills and traditions. But they were not designers in our individualistic and arty understanding of the

profession. The rules are very clear, the geometry of the streets and building plots mixed with the

huge pressure to build at that time results in a reduced freedom for the architecture. Having to deal

with these clear sets of rules leads to amazing buildings even if there is a bad architect behind them.

Its clear that good architects make better looking buildings, but because the urban rules are so clear

even the bad architects can create remarkable buildings in those cities. What we realised was that

this constraint is valuable in the creation of the city. A city needs these rules, and Hong Kong has

these rules, as do all the cities we have studied. What we miss here in Switzerland are these precise

rules. Building laws here are very defensive. They try to reduce the building height and create the

maximum distance between the buildings and in doing this they somehow avoid urbanity. This comes

from an intention to avoid the creation of what we would call a city. Zurich has some interesting block

neighbourhoods from the 19th century. There was a regulation in 1893 that proposed these block

formations following the example of Berlin, and then in 1914 they replaced those rules with the ones

aligned to the garden city. You can see the results in the city today. It is a very un-urban city in terms

of its form. It was an intentional change led by the architects of that time. So we shouldnt

underestimate the position and influence of the architect in these processes its not the investors

who want to make a profit and dont care too much about the form its the architect that gives form

to these forces.

SP: So, on the one hand the architect is irrelevant because the rules are so well established and on

the other the architect is central to the culture of the rule making process. In the first we can assume

that the profession is no longer required, that a house builder could create the city to a set of rules

defined by architects/planners but conversely the good buildings still need to be designed by

architects. It could be that we are somehow arguing ourselves out of a job. In fact we are in a peculiar

period architecturally. In the past cities were mostly built from pattern books and a more concerted

authorship was invested in the most significant public buildings nodal points of social importance

that held the city together. In fact artists and sculptors not architects built significant buildings during

the Renaissance. Commonplace buildings were not given the same exposure and if they were it

would perhaps only be the faade that was beautified. We are now in something of a strange position

as architects one in which we have tried to grasp too much and on the other hand one in which we

have given away some of the responsibilities we probably shouldnt have. My question is whether we

should have to do everything?

CG: No we dont have to do everything. I think we need a clear idea of what the city is today, which in

itself is a big task. This is perhaps the opposite of designing. We are dealing with some of the

remnant ideas of modernism which considers the architect as a genius, supported by the way Le

Corbusier presented himself as an inventor of a new world from painting, to building, to the city

everything. If every architect was to consider themselves to be the inventor of a new world we would

find ourselves with a problem. Even today in master plans for cities we see that architects and

planners are enthralled by this way of working which is a huge problem. You cant go about

constantly inventing the city because it is something that is common, something common to society,

and in order to make it work its rules have to be accepted by the people who use it. If an architect is

given the task to design a piece of a city over a few thousand square meters then it has follow the

rules established by how people actually use the city. We need less invention and a better

understanding of our common culture.

SP: We have to be careful when we use the word invention because of course invention is also very

positive. If we take away invention and ingenuity, even in small-scale things like a window detail then

we would be poorer for it. Perhaps its better to say that we should be careful of self-interested

expression that overrides common expression.

CG: When I use the word invention in a negative sense I mean the nave self-over-estimation where

individuals propose their own private ideas in society.

SP: The idea of private will is worth thinking about. Can we as architects still aspire to serve the

purposes of a common society?

CG: Its a fundamental human question about how we integrate ourselves as unique human beings,

with unique histories, together to form society. This connection is fundamentally a cultural one how

we create things together. I havent thought about it much but probably each generation has to

redefine this relationship. The individuals of the modern age of heroism, of architects and artists, who

had the courage to invent a new world would find themselves with a totally different set of problems

today. Our age is one of a complex globalised society, very different from the world of the 19th

century. We have to acknowledge that not everyone will be as singularly important a figure as Le

Corbusier, but that the role of the architect is one in which we can still propose visions for the

problems of today through each specific project. The only way to find out about the reality of our

common society is to work on the ground with real projects, and to study real functioning cities. We

do this at the ETH. We teach our students that rules are important and that we can learn from rules

from other cities that our creativity has to engage with objective rules, and that objective rules are

not a problem or a restriction for creativity but that they can be create a fertile ground for creation.

Likewise we look at our work in the same way, we ask questions about individual expression and the

author and how they meet with the rules of society and architecture.

SP: Going back to the question of urbanity, you speak about the need for uniformity, not in a bad

sense but more in the sense of a costume, in defining the roles that define our common urban realm.

Then of course there are a whole set of other rules, architectural rules commonly called principles

which you study through the observation of type rules like spatial organisation, structure and maybe

even proportion and composition. Do you deal with those principles in the same way as the larger

planning or urban rules? Does the method of studying the city transpose to the study of the singular

object in the city or do you then revert to a more common approach to learning about architecture at

that level?

CG: What we try to do with the student is to approach the design in a very coherent and logical way.

For instance we check the potential of an urban building type to create public space: What kind of

space, what functional potential, what scenario is linked to this type? And on the other hand: What

kind of architecture does this type produce? How is his structure expressed through a faade? That

means, we somehow try to build up a coherent system of space, type and expression. So far its very

rational. At the same time, I know that in reality, in our office, there are some disturbing elements that

can be absolutely contradictory that bring a completely different angle to the design. Talking of

being honest, of course to be so rational is in some sense a pretence. We follow the logic of a design

up to a point, but there comes a certain stage in which a design can be enriched by contradictory

elements that are completely individually motivated because I want it which is legitimate. We

dont tend to reinvent architecture. Architecture is always about the same issues.

SP: Up until now we have been talking about the rules in quite an abstract way. When I recently met

Peter Mrkli we spoke about the grammar of architecture. He explained that the grammar of a

building is something akin to a language, like the alphabet, that can be understood and therefore

learned. Apart from the most rudimentary principles afforded to it by climate and site conditions, could

you see anything in architecture that relates, like he does, to a common language? At the beginning

of this interview you said something very interesting, about how at a certain point, when it came to

designing a building, the architects/students were suddenly lost. It makes me think that the we just

need to study architecture, study buildings, like you did when you immersed yourself in the buildings

of Northern Italy.

CG: When we study building types from these cities they tend to be anonymous buildings. They are

often pragmatic and in that way tell the student a lot about the rules of architecture, because they

follow a technological, economical and functional logic. They are not singular buildings but merely

representative of a huge group that has evolved over generations or even centuries. The knowledge

of how they dealt with the constraints is condensed in very intelligent solutions. So, studying these

examples with the students is very worthwhile because the objects explain a lot about the rules of

form how a body ties to a faade with openings and how all the components come together. A lot of

these buildings are the opposite of a manifesto, they are not there to prove something, but are the

result of an intelligent considerations, they also happen to be architectonically beautiful in my opinion.

They have clear rules, and I think these clear rules lead to a clear tectonic expression. In those

examples we can learn a lot about the grammar of architecture and of bringing the tectonic elements

together.

SP: Many of the motifs that are adopted by common stock buildings, the pediment, an architrave or a

particular window head detail have generally been derived from model architecture created at the

apex of a culture. In a way the grammar of architecture has come from there. However, our link with

this archaic language is broken. Do you think we can build a new grammar and where do you think

we should start?

CG: Because we live in a very complex society where there arent such clearly defined rules of

perception anymore, the way I perceive a building is very basic, direct and physical. I see the house

as a body and in the body I see elements like openings that are a disturbance of this body and

maybe I wouldnt call it a grammar rather than physical rules that determine how these openings are.

They can be harmonious or disturbing or boring, thats how architecture works through our optical

physical perception and that is why it has rules rules governed primarily by the culture of our own

human body.

You might also like

- Towards an anthropological theory of architecture: Eliminating the gap between society and architectureDocument18 pagesTowards an anthropological theory of architecture: Eliminating the gap between society and architectureEvie McKenzieNo ratings yet

- Typology As A Method of Design Jing-ZhongDocument6 pagesTypology As A Method of Design Jing-ZhongMonica RiveraNo ratings yet

- What Did Dell Upton Mean by Landscape HistoryDocument5 pagesWhat Did Dell Upton Mean by Landscape HistoryAderinsola AdeagboNo ratings yet

- Technological Institute of The Philippines: 938 Aurora BLVD., Cubao, Quezon CityDocument6 pagesTechnological Institute of The Philippines: 938 Aurora BLVD., Cubao, Quezon CityBianca EtcobañezNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Architecture in A Historical Context: January 2013Document20 pagesContemporary Architecture in A Historical Context: January 2013Jubel AhmedNo ratings yet

- Building The DrawingDocument9 pagesBuilding The Drawingdamianplouganou50% (2)

- De SOLA MORALES, Manuel (1992) - Periphery As ProjectDocument7 pagesDe SOLA MORALES, Manuel (1992) - Periphery As ProjectevelynevhNo ratings yet

- A New Theory of Urban Design: Christopher Alexander Hajo Neis Artemis AnninouDocument7 pagesA New Theory of Urban Design: Christopher Alexander Hajo Neis Artemis AnninouHarriet Minaya IngunzaNo ratings yet

- Okan University: Morphogenesis of Space - A Reading of Semiotics in ArchitectureDocument8 pagesOkan University: Morphogenesis of Space - A Reading of Semiotics in ArchitectureLeoCutrixNo ratings yet

- Representation and Context Based DesignDocument10 pagesRepresentation and Context Based DesignIpek DurukanNo ratings yet

- Visuality for Architects: Architectural Creativity and Modern Theories of Perception and ImaginationFrom EverandVisuality for Architects: Architectural Creativity and Modern Theories of Perception and ImaginationNo ratings yet

- About How Eisenman Use DiagramDocument7 pagesAbout How Eisenman Use DiagramPang Benjawan0% (1)

- Size, Image and Architecture of Neo-Liberal EraDocument3 pagesSize, Image and Architecture of Neo-Liberal EraDr Hussein ShararaNo ratings yet

- The Solitude of BuildingsDocument5 pagesThe Solitude of BuildingsMaria Daniela AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- ADS5: Ambiguous Architecture - Royal College of ArtDocument8 pagesADS5: Ambiguous Architecture - Royal College of ArtFrancisco PereiraNo ratings yet

- Research For Research - Bart LootsmaDocument4 pagesResearch For Research - Bart LootsmaliviaNo ratings yet

- John Hejduk's Pursuit of an Architectural Ethos Through Imaginary ProjectsDocument16 pagesJohn Hejduk's Pursuit of an Architectural Ethos Through Imaginary ProjectsАнжела ХайдарNo ratings yet

- Spaces and Events: Bernhard TschumiDocument5 pagesSpaces and Events: Bernhard TschumiRadoslava Vlad LNo ratings yet

- Sara's PortfolioDocument27 pagesSara's PortfolioSara FaeziNo ratings yet

- Architecture Through Cognitive Mapping Capturing and Defining The Experienced AtmosphereDocument6 pagesArchitecture Through Cognitive Mapping Capturing and Defining The Experienced AtmosphereGugu KabembaNo ratings yet

- Brendan Josey Journal FinalDocument119 pagesBrendan Josey Journal FinalÍtalo NevesNo ratings yet

- Drawing Theory: An Introduction: Footprint January 2010Document9 pagesDrawing Theory: An Introduction: Footprint January 2010Bruno SanromanNo ratings yet

- Space: RuangDocument5 pagesSpace: RuangKania Irianty Riahta Br SembiringNo ratings yet

- Cuthbert 2007# - Urban Design... Last 50 YearsDocument47 pagesCuthbert 2007# - Urban Design... Last 50 YearsNeil SimpsonNo ratings yet

- Behind The Postmodern FacadeDocument228 pagesBehind The Postmodern FacadeCarlo CayabaNo ratings yet

- Architectural Models: Legacy and Critical Perspectives: Les Cahiers de La Recherche Architecturale Urbaine Et PaysagèreDocument19 pagesArchitectural Models: Legacy and Critical Perspectives: Les Cahiers de La Recherche Architecturale Urbaine Et PaysagèreHenry JekyllNo ratings yet

- Everyday Urbanism in Amsterdam PDFDocument17 pagesEveryday Urbanism in Amsterdam PDFPhillipe CostaNo ratings yet

- Structuralism in Architecture A DefinitionDocument7 pagesStructuralism in Architecture A DefinitionvikeshNo ratings yet

- Jiamengli 4738217 Position Paper For AR3A160Document7 pagesJiamengli 4738217 Position Paper For AR3A160gkavin616No ratings yet

- Phenomenology and its Problematic Visual RepresentationDocument4 pagesPhenomenology and its Problematic Visual RepresentationXiangyu LiNo ratings yet

- The Hidden Geometry of NatureDocument8 pagesThe Hidden Geometry of NatureChris GrengaNo ratings yet

- On Meaning-Image Coop Himmelb L Au ArchiDocument7 pagesOn Meaning-Image Coop Himmelb L Au ArchiLeoCutrixNo ratings yet

- Moussavi Kubo Function of Ornament1Document7 pagesMoussavi Kubo Function of Ornament1Daitsu NagasakiNo ratings yet

- Drawing Theory An IntroductionDocument9 pagesDrawing Theory An IntroductionCultNo ratings yet

- bEN VAN BERKELDocument5 pagesbEN VAN BERKELsiyue huNo ratings yet

- RadicalityDocument7 pagesRadicalityAlaa RamziNo ratings yet

- Performance/Architecture: An Interview With Bernard TschumiDocument7 pagesPerformance/Architecture: An Interview With Bernard TschumiMohammed Gism AllahNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Practice - Research and Pedagogy in Art, Design, Creative Industries, and Heritage - Vol. 1: Department of Art and Design, The Hang Seng University of Hong KongFrom EverandConceptual Practice - Research and Pedagogy in Art, Design, Creative Industries, and Heritage - Vol. 1: Department of Art and Design, The Hang Seng University of Hong KongNo ratings yet

- Reader 3Document3 pagesReader 3alexNo ratings yet

- Arch 0094 - Architecture An IntroductionDocument385 pagesArch 0094 - Architecture An IntroductionKhant Shein Thaw100% (1)

- Architecture and The SensesDocument3 pagesArchitecture and The SensesMina DrekiNo ratings yet

- Introduction To DisertatieDocument33 pagesIntroduction To DisertatieAndreea BernatchiNo ratings yet

- Architecture as a Cultural PracticeDocument12 pagesArchitecture as a Cultural PracticeAnda ZotaNo ratings yet

- Diagrams On ArchitectureDocument23 pagesDiagrams On ArchitecturearthurzaumNo ratings yet

- Research On Architectural ImaginationDocument8 pagesResearch On Architectural ImaginationCon DCruzNo ratings yet

- Constructs 2011 FallDocument28 pagesConstructs 2011 FallAron IoanaNo ratings yet

- Interview With Bruno LatourDocument9 pagesInterview With Bruno Latourbp.smithNo ratings yet

- 02.toward An Architecture of Humility - Pallasmaa PDFDocument4 pages02.toward An Architecture of Humility - Pallasmaa PDFMadalina GrecuNo ratings yet

- Research in Art and Design: An Analyzing Essay by Andreas SjöbergDocument3 pagesResearch in Art and Design: An Analyzing Essay by Andreas SjöberghejandreijNo ratings yet

- Wolfflin, From A To A Psychology of ArchitectureDocument4 pagesWolfflin, From A To A Psychology of ArchitectureNicoletta Rousseva100% (1)

- The City Is Not A Postcard - PerezGomezDocument3 pagesThe City Is Not A Postcard - PerezGomezRichard ten BargeNo ratings yet

- In The Manuscript Right: Master'S DissertationDocument30 pagesIn The Manuscript Right: Master'S DissertationMəleykə HüseynovaNo ratings yet

- The New Urban Question Interwiev SecchiDocument9 pagesThe New Urban Question Interwiev SecchiA Bao A QuNo ratings yet

- Unromantic Castle and Other Essays (London: Thames and Hudson, 1990), Pp. 257Document5 pagesUnromantic Castle and Other Essays (London: Thames and Hudson, 1990), Pp. 257roxanaNo ratings yet

- 0.1 HistoriographyDocument31 pages0.1 HistoriographyAnu KumarNo ratings yet

- Aldo Rossi - Chapter 3Document13 pagesAldo Rossi - Chapter 3Daniel BerzeliusNo ratings yet

- 3 - VenturiDocument4 pages3 - VenturiChris MorcilloNo ratings yet

- The Big Rethink - Lessons From Peter Zumthor and Other Living MastersDocument16 pagesThe Big Rethink - Lessons From Peter Zumthor and Other Living MastersJames IrvineNo ratings yet

- Egyptian Architecture-Columnar Style & Massive TombsDocument5 pagesEgyptian Architecture-Columnar Style & Massive Tombsvartika chaudharyNo ratings yet

- F009-Loading TableDocument2 pagesF009-Loading Tableloc khaNo ratings yet

- 2022.11.04 Chlorination BuildingDocument5 pages2022.11.04 Chlorination BuildingathavanNo ratings yet

- Types of Pavements - Flexible Pavements and Rigid PavementsDocument2 pagesTypes of Pavements - Flexible Pavements and Rigid PavementsHitesh YadavNo ratings yet

- General Line Products: Rapid-Lok Connection Plate SystemsDocument3 pagesGeneral Line Products: Rapid-Lok Connection Plate SystemsGuilherme MendonçaNo ratings yet

- Arch-3.1-Aluminium Doors and WindowsDocument3 pagesArch-3.1-Aluminium Doors and WindowsSherazNo ratings yet

- 1 Furniture Layout PlanDocument1 page1 Furniture Layout PlanAhmad Ashraf AzmanNo ratings yet

- Conclusion: Every System Has Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument1 pageConclusion: Every System Has Advantages and DisadvantagesOAV DaikinNo ratings yet

- Full Inspection Report of The Richards Covered Bridge in Columbia CountyDocument61 pagesFull Inspection Report of The Richards Covered Bridge in Columbia CountyPittsburgh Post-GazetteNo ratings yet

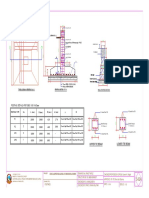

- Foundation footing detailsDocument1 pageFoundation footing detailsBibek BasnetNo ratings yet

- Design documentation for residential homeDocument30 pagesDesign documentation for residential homeMohd GhifaryNo ratings yet

- Dar (Civil) IIDocument888 pagesDar (Civil) IIShyam Kumar100% (1)

- M.aitchison PublicationsDocument2 pagesM.aitchison PublicationsRuxandra VasileNo ratings yet

- AD6 - Major Plate #1 Research PaperDocument14 pagesAD6 - Major Plate #1 Research Papervicente3maclangNo ratings yet

- A1-Boundary & Septic Tank DetailsDocument1 pageA1-Boundary & Septic Tank DetailsFleming MwijukyeNo ratings yet

- Diaphargm Wall Construction DetailsDocument48 pagesDiaphargm Wall Construction DetailsAkshay Joshi100% (1)

- Industrial Design For ArchitectureDocument3 pagesIndustrial Design For ArchitectureRadhikaa ChidambaramNo ratings yet

- Construction Drawing: Wet Kitchen Dry Kitchen Dry KitchenDocument1 pageConstruction Drawing: Wet Kitchen Dry Kitchen Dry KitchenrajavelNo ratings yet

- Sathyaprakash - FC and Demolition QuoteDocument4 pagesSathyaprakash - FC and Demolition QuoteSad JokerNo ratings yet

- House ExtensionDocument2 pagesHouse ExtensionChristian HindangNo ratings yet

- BQS401 Specification - Alcove Condominium Sime DarbyDocument48 pagesBQS401 Specification - Alcove Condominium Sime DarbyMOHAMAD AMIR BIN HALID0% (1)

- Building Enclosure Commissioning: Standard Practice ForDocument19 pagesBuilding Enclosure Commissioning: Standard Practice ForAdán Cogley CantoNo ratings yet

- BoqDocument21 pagesBoqKline Sky J Line100% (2)

- Concrete MixesDocument2 pagesConcrete MixesRm1262No ratings yet

- February 28, 2014: Continuous Load Path: Wall BracingDocument15 pagesFebruary 28, 2014: Continuous Load Path: Wall BracingIonFlorentaNo ratings yet

- Resale: Honey, I'm HomeDocument1 pageResale: Honey, I'm HomeSarahMagedNo ratings yet

- Liter Tank DetailDocument281 pagesLiter Tank DetailrkpragadeeshNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Solids and Structures Volume 2 Issue 2 1966 (Doi 10.1016/0020-7683 (66) 90018-7) Jacques Heyman - The Stone Skeleton PDFDocument43 pagesInternational Journal of Solids and Structures Volume 2 Issue 2 1966 (Doi 10.1016/0020-7683 (66) 90018-7) Jacques Heyman - The Stone Skeleton PDFManuelPérezNo ratings yet

- Reinforced Concrete Standards UpdateDocument5 pagesReinforced Concrete Standards Updatemnoim5838No ratings yet