Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Advertising of Service

Uploaded by

Kumar GouravOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Advertising of Service

Uploaded by

Kumar GouravCopyright:

Available Formats

http://jsr.sagepub.

com

Journal of Service Research

DOI: 10.1177/109467059921008

1999; 2; 98 Journal of Service Research

Banwari Mittal

The Advertising of Services: Meeting the Challenge of Intangibility

http://jsr.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/2/1/98

The online version of this article can be found at:

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Center for Excellence in Service, University of Maryland

can be found at: Journal of Service Research Additional services and information for

http://jsr.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://jsr.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions:

http://jsr.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/2/1/98 Citations

at SAGE Publications on May 20, 2009 http://jsr.sagepub.com Downloaded from

JOURNAL OF SERVICE RESEARCH / August 1999 Mittal / ADVERTISING SERVICES

The Advertising of Services

Meeting the Challenge of Intangibility

Banwari Mittal

Northern Kentucky University

Service advertisers often are confronted with the problem

of how best to communicate the intangible qualities of a

service to their target audiences. In this conceptual arti-

cle, the author describes what intangibility means, dis-

cusses how it influences the service advertising task, and

derives propositions to handle that task. The article (a)

identifies five conceptual properties of intangibility, (b)

describes the advertising challenge of each, (c) suggests

approaches to meet each challenge, and (d) elucidates

the power of transformational advertising in embedding

intangible service performance into a consumers life ex-

periences. The author argues that in services, intangibil-

ity can contribute to value rather than detract fromit and

that it is well within the advertisings special talent to

communicate intangibility. The author advances propo-

sitions to guide copy and creative strategy for service ad-

vertising managers.

It is by now a universally accepted proposition that the

marketing of services is different from the marketing of

physical goods. Shostack (1977) raised the issue first in a

Journal of Marketing article titled Breaking Free From

Product Marketing. Later, Berry (1980) reiterated that

Services Marketing Is Different. Since then, an impres-

sive body of literature has surfaced, idiosyncratic to ser-

vices (e.g., GAP model, SERVQUAL, servicescapes,

personalization), certifying the different-ness of service

marketing (Bitner 1992; Fisk 1981; Lovelock 1983; Mittal

and Lassar 1996, 1998; Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry

1988; Tripp 1997; Zeithaml, Parasuraman, and Berry

1990). This different-ness poses a challenge for all aspects

of marketing including advertising. It is argued that due to

the intangibility of services, communicating about ser-

vices becomes difficult and requires special considera-

tions in copy strategy and creative execution (Day 1992;

Grove, Pickett, and LaBand 1995; Legg and Baker 1987).

Because intangibility is widely cited as the root source of

service advertising difficulty, the question of exactly how

intangibility blocks effective communication requires fur-

ther examination. The purpose of the present article is to

understand intangibility as a characteristic of services, ex-

amine howit affects service advertising, and propose some

approaches to overcoming the challenge of communicat-

ing about the intangible aspects of services.

This article is organized as follows. First, it is argued

that all services do have some tangible elements. Accord-

ingly, service advertising can use the tangible aspects of

the service to create brand identity, to some extent. How-

ever, when the service brands competitive appeal lies in

the intangible (rather than the tangible) aspects of the ser-

vice, the task of communicating the intangible becomes

unavoidable. This calls for an understanding of the nature

of intangibility itself. Accordingly, froma reviewof litera-

ture, five properties of intangibility are identified: incorpo-

real existence, abstractness, generality, nonsearchability,

and mental impalpability. On closer scrutiny, however, it is

proposed that only the first of these five properties is inevi-

table; the other four often tend to be present but are not in-

trinsic to intangibility. It is argued that by following certain

strategies, the advertising of intangible service features

can overcome these undesirable properties. The article

outlines these strategies, whose effect is to transform the

Helpful comments fromJulie Baker andMargaret Myers, and fromthe journal editor and reviewers, are gratefully acknowledged.

Journal of Service Research, Volume 2, No. 1, August 1999 98-116

1999 Sage Publications, Inc.

at SAGE Publications on May 20, 2009 http://jsr.sagepub.com Downloaded from

abstract into the concrete, the general into the specific, the

nonsearchable into the searchable, and the mentally impal-

pable into the palpable. Then, it is argued that, in fact,

many physical products also appeal to consumers with

their intangible benefits and that advertising professionals

already have handled this challenge well. They accom-

plish this by employing a special type of advertising

called transformational advertising. This form of adver-

tising is discussed as a way of executing the service ad-

vertising strategies outlined earlier. The key points of the

article are summarized as a set of eight propositions, and

from these, managerial guidelines are derived and pre-

sented. The central lesson of the article is that rather than

bemoan intangibility, service marketers can leverage it in

their advertising.

THE INTANGIBILITY OF SERVICES

Whereas it is generally agreed that service marketing

is different (Deighton 1994; Mittal and Baker 1998; Rust

and Oliver 1994), the characterization of services as be-

ing intangible has been debated. Lovelock (1994), for ex-

ample, argues that most physical products are (or should

be) offered as product-plus; that is, some sort of service

is attached to the product such as an in-home appliance

maintenance service contract. On the other hand, many

services are accompanied by some physical product such

as an airline service that includes the airplane, in-flight

food, and the like. Thus, market offerings range widely

on a continuum of pure products to pure services (Rust

1995; Shugan 1994; Wright 1995). For this reason, ad-

vertisers of products and services alike face the choice of

featuring physical product elements and/or nonphysical

service elements. But physical product itself seldom suf-

fices as an effective consumer appeal; even pure products

often are sold on nonphysical product benefits such as the

prestige or trendy-ness of a brand of furniture, the mys-

tique of a brand of motorcycle, and the coolness of a

brand of shoes. If product advertising can communicate

such intangible benefits, then it should not be an insur-

mountable task for service marketers to effectively ad-

vertise the nonphysical aspects of their services. To

support this conclusion, this article examines the essen-

tial properties of intangibility (applied to service and

physical product benefits alike) and how each of those

properties influences the nature of communication tasks.

Before turning to a conceptual discussion of intangibility

per se, however, let us briefly reviewthe current literature

for cues on how intangibility is believed to affect the ad-

vertising of services.

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

The special challenges of service advertising have been

discussed by a number of service researchers. In one of the

early essays on the topic, George and Berry (1981) argue

that service advertising is problematic because of three

features of services, namely, that (a) service is a perfor-

mance delivered by service employees, (b) there is vari-

ability in the delivery of services, and (c) the service

product is intangible. In fact, however, even the first two

characteristics, performance and variability, are related to

intangibility; variability occurs because the service is not a

physical thing that can be subjected to tight design specifi-

cations and mass-produced on assembly lines. To address

these aspects of intangibility, George and Berry suggest a

number of guidelines for advertising. First, because ser-

vice is a performance, the service employees behavior

plays an important role; therefore, some of the advertising

should be directed at employees. Second, because of the

variability, service customers perceive a risk and, conse-

quently, seek word-of-mouth recommendations; there-

fore, service advertising should stimulate word of mouth.

Third, to handle the problem of intangibility, advertising

should make the service tangible by using tangible cues,

that is, concrete images such as the bull in Merrill Lynchs

advertisements and the umbrella in Travelers Insurance

advertisements. Later, it is shown that this last suggestion

is of limited utility. This is because these tangible aspects

help to create brand identity but often do little to convey

the intangible aspect of service.

Legg and Baker (1987) argue that the intangible nature

of services presents problems to consumers at both the

pre- and postpurchase stages. At the prepurchase stage,

consumers have difficulty understanding the service and

forming evoked sets; at the postpurchase stage, consumers

have difficulty evaluating the service experience. To help

the prepurchase assessment, Legg and Baker suggest

(echoing George and Berrys [1981] suggestions) the use

of vivid advertisementsachieving vividness by tangible

cues, concrete language, and/or dramatization. They fur-

ther suggest that service advertisements should feature

behind-the-scenes operations to indicate service quality

both before and after the purchase. Finally, they suggest

that an advertisement should present a service script

(i.e., a description of what will happen during the service)

toset (or correct) customer expectations about the service.

Addressing the same problem of intangibility, Berry

and Clark (1986) propose four strategies of tangibaliza-

tion: association, physical representation, documenta-

tion, and visualization. Association is the linking of the

service to an extrinsic person, place, or object (e.g., Merrill

Mittal / ADVERTISING SERVICES 99

at SAGE Publications on May 20, 2009 http://jsr.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Lynchs bull, Heather Locklear for Ballys Fitness). Physi-

cal representation is showing tangibles that are directly or

peripherally parts of a service (e.g., buildings, vans, em-

ployees). Documentation is the featuring of objective data

and factual information. Finally, visualization is a vivid

mental picture of a services benefits or qualities such as

showing passengers on a cruise ship having fun. This arti-

cle includes many of these ideas in an expanded set of sug-

gested advertising strategies.

Some recent literature has departed from suggesting

specific ad strategies to reflecting on howadvertising com-

municates meaning. In an illuminating literary analysis of

copy and visual elements, Stern (1988) shows howtwo dif-

ferent financial service companies (Merrill Lynch and Fi-

delity) communicate their individualistic and differentiated

personalitythe company mystique, as Stern calls it.

Sterns essay, presenting a critics interpretation rather

than the audiences interpretation, argues that a carefully

crafted advertisement is quite capable of communicating

the key (intangible) attributes of a service offering. Also

focusing on copy strategy, Padgett and Allen (1997) distin-

guish two types of ads: argumentative and narrative. Argu-

mentative ads present and persuade by using objectively

verifiable appeals and benefit claims. By contrast, narra-

tive ads persuade by a story, a set of events in time depicted

by actors or conveyed by another form such as a song,

dance, or mime. That is, a narrative ad, rather than an argu-

mentative one, dwells on the subjective human experience.

Because a service is essentially an experience that is sub-

jectively encoded by the customer, the narrative ad, Padg-

ett and Allen propose, is likely to be more effective for

service advertising.

The foregoing literature addresses the important issue

of intangibility, points to the difficulty it creates, and iden-

tifies several approaches to overcome it. However, the key

concept of intangibility has not been scrutinized closely, a

task germane to a more theoretical and systematic devel-

opment of advertising strategies to overcome the chal-

lenge of intangibility. To further this literature, the nature

of intangibility itself is examined more closely in the next

section.

INTANGIBILITY: THE CONCEPT AND

ITS PROPERTIES

The concept of intangibility as a characteristic of ser-

vices is recognized in virtually all writings in the service

literature. For example, Lovelock (1996) recognizes that

service performance itself is basicallyanintangible (p. 7).

Rust, Zahorik, and Keiningham (1996) describe intangibil-

ity as follows: Pure services . . . cannot be seen or touched.

They are ephemeral performances (p. 8). Zeithaml and

Bitner (1996) describe it as follows: Because services are

performances or actions rather than objects, they cannot be

seen, felt, tasted, or touched in the same manner that we

can sense tangible goods (p. 19). Later, Zeithaml and Bit-

ner allude to services being difficult for the consumer to

grasp even mentally (p. 19). In a more focused discussion

of intangibility, Breivik and Troye (1996) suggest three di-

mensions to intangibility: abstractness, generality, and

nonsearchability (discussed later). The present article

builds on these discussions of intangibility to formulate a

more formal description of the concept, identifying its key

properties.

A useful place to start a formal treatment of intangibil-

ity is with a dictionary definition of the term. Websters

NewWorld Dictionary (Prentice Hall, 1994) defines intan-

gibility as that which cannot be touched or grasped, is in-

corporeal, is impalpable (p. 701). From this definition,

two properties of intangibility are discerned: mental im-

palpability (which also was mentioned by Zeithaml and

Bitner 1996) and incorporeal existence. Adding to these

the Breivik and Troye (1996) list (which consists of ab-

stractness, generality, and nonsearchability) yields an ini-

tial list of five characteristics. Let us consider themone by

one.

Incorporeal existence. The first property refers to the

fact that the service product is not made out of physical

matter and does not occupy physical space. Note that the

intangible nature of the service itself is referred to here, not

the service delivery system, which might well be entirely

tangible. A banking service delivery system, for example,

has many tangible elements (e.g., branch building, auto-

matic teller machines, human tellers). However, the core

banking servicethe safekeeping of customers money

and other valuables with convenient, just-in-time access

itself is nonphysical (i.e., incorporeal).

Abstractness. Proposed by Breivik and Troye (1996),

abstractness refers to something that is thought of apart

from any particular instances or material objects (Pren-

tice Hall, 1994). Abstract paintings, for example, are those

that do not depict concrete objects in naturally occurring

configurations, as in Picassos paintings. By this defini-

tion, service benefits such as peace of mind, happiness,

and financial security all are abstract rather than concrete.

Because abstract images do not have one-to-one corre-

spondence with the objects of the material world, it be-

comes difficult to visualize and understand them.

Generality versus specificity. Generality, another di-

mension suggested by Breivik and Troye (1996), refers to

a class of things, persons, events, properties, or the like, as

opposed to specificity, which pertains to one specific ob-

ject, person, event, or the like. Whereas the opposite of ab-

stract is concrete, the opposite of general is specific. To

100 JOURNAL OF SERVICE RESEARCH / August 1999

at SAGE Publications on May 20, 2009 http://jsr.sagepub.com Downloaded from

differentiate the two, consider food on an airline. Food is

not an abstract entity, but it can be presented as a generality

(e.g., superior food) or as a specificity (e.g., Our en-

tres are made fromscratch). Abstractness and generality

are related but not identical; all abstract claims also are

general, but not all general claims are abstract. Thus, se-

curity and peace of mind as service benefits both are

abstract (i.e., not concrete) and general (i.e., not specific),

but superior food service and clear phone reception

are general but not abstract. Generality makes the service

benefit vague and, therefore, detracts from persuasion.

Nonsearchability. Darby and Karni (1973) advanced

the idea of three types of attributes: search, experience, and

credence. Search attributes are those that can be evaluated

before the purchase. Experience attributes require the con-

sumer to actually experience the product or service. Cre-

dence attributes can be neither searched nor evaluated by

experience; rather, they have to be taken on faith.

Because service is a performance, and it cannot be pro-

duced in advance for prepurchase inspection, it is said to

lack search quality (Zeithaml, 1981). Consider, for exam-

ple, a surgical procedure for a gallbladder removal. It is not

an abstract service, nor is generality an issue. It is just that

the skill of the surgeon is not searchable in that a con-

sumer cannot inspect or observe it directly.

Mental impalpability. This final property comes from

the dictionary definition cited earlier. Some services are

too complex, multidimensional, or nascent; consequently,

it is difficult to mentally grasp them. Although abstract-

ness and/or generality may contribute to this dimension,

there need be no one-to-one correspondence. A vacation

trip to a foreign country is neither abstract nor general; yet,

it is mentally impalpable, at least for persons not exposed

to foreign cultures. Likewise, a yoga class, a virtual reality

recreational game, financial trading in futures, a reengi-

neering consulting service, etcetera, are examples of ser-

vices that are relatively difficult to mentally grasp. Nor are

incorporeal existence and impalpability mutually redun-

dant, at least not entirely. Many physical phenomena may

be impalpable (e.g., experiments in physics and chemistry,

complex mechanical or electronic devices), and many

nonphysical events are palpable (e.g., the concepts of per-

jury, kindness, happiness). What causes impalpability is

the absence of prior exposure, familiarity, or knowledge

needed for interpretation.

Recap. What, then, is intangibility? The preceding dis-

cussion suggests that of the five properties discerned from

the literature, incorporeal existence is the inevitable and

defining property of intangibility; it is true by definition

(intangibility = incorporeal existence). The other four

properties arise from this fundamental property, although

not inevitably and not all of themsimultaneously. It is their

incorporeal existence that makes intangible service prod-

ucts nonsearchable and impalpable (and sometimes also

abstract and general). Intangibility lends itself more natu-

rally to these other properties; therefore, unmanaged, in-

tangible services and communications about them are

likely to become more abstract, general, nonsearchable,

and impalpable and, consequently, to prove ineffective in

persuasion. But communications about intangible ser-

vicesintangibility defined as incorporeal exis-

tencecan be managed to avoid or minimize these four

problem properties.

Advertising Strategies to Manage Intangibility

Advertising professionals employ a number of execu-

tion approaches (i.e., advertising strategies) such as dem-

onstration, comparison, testimonial, and slice of life

(Belch and Belch 1998, p. 275). To successfully communi-

cate the intangible service features, service advertisers

need a special set of advertising strategies. These strate-

gies are assembled in Table 1 along with the definitions of

various terms involved. Different strategies are called for

to override each specific property of intangibility, as dis-

cussed in what follows.

INCORPOREAL EXISTENCE

Incorporeal existence makes advertising difficult due

to a lack of any physical entity to photograph or even ver-

bally describe. This difficulty is resolved, with some suc-

cess, by using ancillary physical elements as tangible

symbols of the service product. Even when the core ser-

vice is itself intangible (e.g., education), the service deliv-

ery system often is tangible (e.g., the classroom, the

teacher), and it is this that forms the substance of at least

the visual images in much of service advertising. Thus, the

employees, their uniforms, physical plant, vehicles, com-

pany stationary, and the likeall woven in a unified color

and stylistic graphics (e.g., red for AVIS car rental, brown

for UPS)are used to give substance and form to service

advertising. This is the strategy that Berry and Clark

(1986) term physical representation.

What exactly does physical representation as an ap-

proach to tangibalization accomplish? A review of litera-

ture and various service advertisements suggests that the

tangibles shown in advertising help in three ways: (a) by

creating an identity for the service firm by consistently

showing the same visual images of the tangible elements;

(b) by serving as surrogate cues to quality (e.g., the profes-

sional appearance of employees or modern furnishings

and equipment might lead consumers to believe that the

firms core service itself might be of a high quality

(Zeithaml and Bitner 1996, p. 122); and (c) sometimes by

Mittal / ADVERTISING SERVICES 101

at SAGE Publications on May 20, 2009 http://jsr.sagepub.com Downloaded from

promoting an inference of some specific service attribute

(as opposed to an impression of overall quality), as in the

use of a bull to stand for bullish investing by Merrill Lynch.

That is, they might create what Aaker (1991) calls brand

associationsassociating a brand with a specific feature

or property. As Berry and Parasuraman (1991) suggest, a

brands meaning to the customer (i.e., what the brand

stands for) depends on a coherent presentation of various

visual elements of the service delivery system. Each of the

foregoing three effects, however, requires a careful selec-

tion of the tangible element. For identity, the ad must show

a unique visual image of the service firm. For quality of

service, the tangibles shown must themselves reflect qual-

ity. For specific brand associations, the selected tangible

element must cue the intended service attribute. Even

when these effects are attained, it should be recognized

that not all intangible service benefits (e.g., peace of mind)

lend themselves to be reflected in or cued by physical rep-

resentation.

Proposition 1a: In service advertising, featuring ancil-

lary physical elements of the service delivery system

serve as tangible symbols of the service. This physi-

cal representation strategy can help (a) by establish-

ing the service brand identity, (b) as a surrogate (i.e.,

indirect) indicator of quality, and (c) in conveying

brand associations.

Proposition 1b: These benefits of physical representa-

tion are not automatic; they require uniqueness for

identity, specific surrogate cues to signal quality,

and incorporation of specific physical elements to

build relevant brand associations.

Proposition 1c: The physical representation strategy does

not address the task of directly communicating those

intangible benefits that do not reside in or stem from

the tangible aspects of the service delivery system.

It is the second effect of tangibalization (i.e., an impres-

sion of quality) that renders physical things a role as an

evaluative dimension in SERVQUAL, a scale to assess

customer-perceived service quality (Parasuraman,

Zeithaml, and Berry 1988). This recommendation (i.e.,

tangibalization by physical representation) is the most

cited remedy in service communications literature (Berry

and Clark 1986; Shostack 1977; Stafford 1996). Yet, it

should not be assumed that using such physical props ren-

ders the intangible service itself or its intangible benefits

fully communicated. For example, the physical represen-

tation by showing a five-star hotels lobby would do noth-

ing to communicate the hotels responsive housekeeping

service. This brings us to a discussion of other properties

given that these tend to accompany intangibility.

GENERALITY

The solution for generality is to make the message

claimspecific. Punctuality of an airline (a benefit stated as

a generality) can be made specific, for example, by show-

ing a comparative chart of scheduled versus actual arrival

times for a sample of flights (i.e., by depicting specific in-

102 JOURNAL OF SERVICE RESEARCH / August 1999

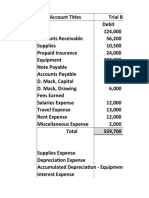

TABLE 1

Definitions of Basic Terms and Strategies in Services Advertising

Basic terms

Objective claim A message claim that can be verified objectively (e.g., on-time delivery)

Subjective claim A message claim that is experienced only subjectively by the perceiver because it cannot be measured objectively

(e.g., courteous service)

Service feature A characteristic or quality of the service input or process (e.g., punctuality)

Customer benefit The benefit the customer receives from the service, that is, an outcome of the service (e.g., secure future)

Concept An idea that exists in the mind (e.g., a responsive service, financial security)

Episode An empirical event that unfolds in the real world, that is, an instance of responsive service being delivered

Documentation Showing facts and figures

Service process A sequence of activities of the service delivery system and employees

Service performance A specific service event in the service process (e.g., the completion of registration at a hotel, the arrival of a plane)

Service consumption The activity of customers in their consumption role

Advertising strategies

Physical representation Showing some visual components of the service

System documentation When the facts and statistics pertain to the service delivery system (e.g., number of planes an airline has)

Performance documentation When the statistics pertain to service performance (e.g., average lost baggage statistic)

Consumption documentation A consumer documenting his or her experience (e.g., testimonial)

Service process episode A depiction of the entire service delivery process

Case history process episode A variant of the service process episode; presents a case history of one service performance delivered to a

specific client

Service performance episode A specific event being performed by the service system

Service consumption episode A service being received and its experience being enjoyed by the consumer

at SAGE Publications on May 20, 2009 http://jsr.sagepub.com Downloaded from

stances of on-time performance). This strategy is termed

documentation, borrowing from Berry and Clark (1986),

but it is limited here to its literal meaning of showing facts

and figures (and excluding other forms of documentation

such as episode filming). Furthermore, and more specifi-

cally, this approach it termed system documentation when

the facts and statistics pertain to the service delivery sys-

tem (e.g., number of planes the airline has) and perfor-

mance documentation whenthe statistics pertaintoservice

performance (e.g., average lost baggage statistic).

However, not all intangible benefits are performance

facts or objective claims. Some are subjective claims

such as responsive housekeeping service in a hotel. The

generality of such subjective claims can be overcome by

depicting a particular service performance episode that

contains a specific enactment of the claimed service fea-

ture such as a hotels staff getting a guests suit dry-cleaned

at an odd hour and on short notice.

Proposition 2a: If the message needs to focus on objec-

tive service features, then the generality of these

service features can be made specific by presenting

statistics on delivery system resources or system

performance (i.e., the system or performance docu-

mentation strategies).

Proposition 2b: If the message needs to focus on subjec-

tive features, then their generality can be made spe-

cific by depicting a specific service episode that

exemplifies the subjective feature claim, that is, by

using a service performance episode strategy.

SEARCHABILITY

Basically, because intangibles cannot be directly

searched before purchase and use, one seeks evaluations

from others who have experienced the service in the past.

That is, the experience quality of intangible services is

communicated to new customers by communicating the

experience of past customers (e.g., by testimonials) or by

facilitating this communication from past users (e.g., by

word of mouth). These two approaches are termed con-

sumption documentation. Also, the credence quality of the

intangible service can be communicated by the service

marketer by documenting its success history or independ-

ently audited performance claims, a strategy termed per-

formance documentation here (e.g., 800 laser surgeries

done, complication rate .03%).

Proposition 3a: Nonsearchability of intangibles can be

addressed by documenting prior success record if

the message pertains to an objective feature that can

be summarized as a statistic (performance docu-

mentation strategy).

Proposition 3b: Nonsearchability of intangibles can be

addressed by obtaining client testimonials and

stimulating word of mouth if the message pertains to

a subjective outcome/benefit such as customer satis-

faction (consumption documentation strategy).

ABSTRACT SERVICE

Abstract service benefits (e.g., happiness) can be made

concrete by evoking particular instances of those benefits.

Happiness can be concretized, for example, by depicting

concrete instances of service recipients made happy. In

general, then, abstract service benefits can be made con-

crete by depicting what are termed service consumption

episodes. In this strategy, consumers are depicted con-

suming the service and, as an outcome, receiving the fo-

cal intangible benefit. This is akin to Berry and Clarks

(1986) visualization, except that it need not be limited to

the visual mode. Vivid prose or poetry can make incorpo-

real and/or abstract experience come alive. For example, a

recent Amtrak ad uses a narrative to convey the joy of

spending quality time with ones loved ones (Exhibit 1).

Proposition 4: Abstractness of service benefits can be

made concrete by depicting a service benefit epi-

sode, here termed the service consumption episode

strategy.

IMPALPABILITY

Finally, how to overcome impalpability? The root

source of impalpability is unfamiliarity rather than intan-

gibility; intangibility keeps entities from becoming famil-

iar because one rarely is exposed to them in everyday life

(e.g., one does not see laser surgery that others might have

undergone). An approach to making such services men-

tally graspable is to reveal exactly what will transpire or

enumerate exactly what benefits will accrue. This can be

done via a staged exhibition of a service delivery process,

say, captured on a videotape (e.g., videotapes of medical

procedures). This approach is termed a service process

episode. This is the mass advertising equivalent of what

Bitner et al. (1996, 1997), in interpersonal communica-

tions, call service previews; the service staff review the

procedure with the customer. Arelated approach is to pre-

sent a case history showing or narrating what the firm did

for a specific client and in what way it solved the clients

problem. This approach is termed a case history process

episode.

Proposition 5: Mental impalpability of services is ame-

liorated by presenting a step-by-step depiction or

explanation of the service process. This depiction is

situated either in a hypothetical episode (service

process episode) or, when client identity can be re-

vealed, in a client-specific history (case history pro-

cess episode).

Mittal / ADVERTISING SERVICES 103

at SAGE Publications on May 20, 2009 http://jsr.sagepub.com Downloaded from

EXHIBIT 1 1

0

4

a

t

S

A

G

E

P

u

b

l

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

s

o

n

M

a

y

2

0

,

2

0

0

9

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

j

s

r

.

s

a

g

e

p

u

b

.

c

o

m

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

In the process episode of either subtype, the category of

service itself is being demystified, regardless of whether it

refers to the total service (e.g., What is benchmarking

consulting service?) or a specific portion of it (e.g., How

does remote hotel check-in work?).

For illustration, consider a recent print ad by Andersen

Consulting. The ad shows a large picture of an elephant

with the headline, OK, nowfloor it. The body copy goes

on to explain that often the change efforts initiated by top

management fail to reach lower levels and that Andersen

Consulting helps management to create a seamless link-

age of all the essential enterprise components: strategy,

technology, process, and people. The ad and its pictorial

depiction refreshingly echo the management challenge of

taming an organizations stodginess. Yet, it sheds no light

on what exactly the consulting firmdoes offer, thereby do-

ing nothing to reduce impalpability. By contrast, Sprint

uses a case history approach in one of its recent ads, an ap-

proach that makes its business network service relatively

more palpable (Exhibit 2).

Table 2 summarizes these strategies, grouped under

three broad categories: physical representation, documen-

tation, and episodes. Documentation has three subtypes:

system, performance, and consumption documentation.

Episode has four subtypes: consumption, performance,

process, and case history episodes. Each of the eight strate-

gies addresses a particular property of intangibility. Like

the four properties they seek to overcome, these strategy

solutions can remain distinct in practice. For example,

consumption documentation such as a testimonial from a

successful recipient of brain surgery helps to overcome

nonsearchability but does not make it less impalpable,

whereas a step-by-step depiction of the service process

(service process episode) makes it palpable but does not

address nonsearchability (e.g., Is the surgeon any

good?).

Note that the strategies defined in these propositions

address the properties that generally attach themselves to

intangible services; they do not do away with the need for

communicating the intangible (i.e., incorporeal) service

benefits to the customer. Indeed, all the strategies except

physical representation embrace intangibles. Of these, the

three documentation strategies are relatively straightfor-

ward to implement. In these strategies, the feature or as-

pect of service is reduced to an objective fact or document,

and these facts are simply presented in the advertise-

ment in a descriptive copy (what Padgett and Allen 1997

call argumentative copy). Their believability depends, of

course, on the credibility of the documents source, just as

the communication of the tangibles does (e.g., This shoe

is made of genuine leather), but at least the problemprop-

erties of intangibility are resolved by the factual nature

of message content by itself. By contrast, the four episode

strategies depend on effective execution, even to fully

overcome the problem properties of intangibility. This is

because the intangible service aspect contained in the epi-

sode still is subjective, and howthe episodes are presented

influences whether or not the concreteness, specificity,

and palpability are achieved. This requires an understand-

ing of the creative platform that advertising employs to

communicate the subjective and the intangible. That plat-

form is transformational advertising, discussed next.

Transformational Advertising: The Key

to Intangible Communication

Transformational advertising is image advertising that

changes the experience of buying and consuming the prod-

uct (Puto, 1986; Wells, Burnett, and Moriarty 1995). Im-

age is an association with a personality, lifestyle, use/

occasion, prestige level, custom/culture, or mood. Image

advertising generally takes two forms, one grounded in the

Mittal / ADVERTISING SERVICES 105

TABLE 2

Services Advertising Strategies Matched

With the Properties of Intangibility

Property of

Advertising Strategy Intangibility Proposition Description

Physical representation Incorporeal existence 1 Show physical components of service

Documentation

System documentation Generality 2a Objectively document physical system capacity

Performance documentation Generality 2a Document and cite past performance statistics

Nonsearchability 3a Cite independently audited performance

Consumption documentation Nonsearchability 3b Obtain and present customer testimonials

Episodes

Service consumption episode Abstractness 4 Capture and display typical customers benefiting from the service

Service performance episode Generality 2b Present a vivid story of an actual service delivery incident

Service process episode Impalpability 5 Present a vivid documentary on the step-by-step service process

Case history episode Impalpability 5 Present an actual case history of what the firm did for a specific client

at SAGE Publications on May 20, 2009 http://jsr.sagepub.com Downloaded from

EXHIBIT 2

1

0

6

a

t

S

A

G

E

P

u

b

l

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

s

o

n

M

a

y

2

0

,

2

0

0

9

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

j

s

r

.

s

a

g

e

p

u

b

.

c

o

m

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

tangible product and one independent of the tangible prod-

uct. In the first form, the image being created is anchored

in the physical composition of the product. That is, without

the product being what it is, the image could not be sus-

tained; advertising merely, but importantly, communicates

and advances that image (e.g., BMW as an ultimate driv-

ing machine). The second type of image advertising, the

one more extreme, is where the physical composition of

the product has nothing to do with the experience that im-

age advertising strives to create (Aaker and Stayman 1992;

Shimp 1997, pp. 268-69). A prime example is Marlboros

image of an outdoorsy, individualistic personality. It is the

Marlboro advertising that transforms the experience of

smoking the brand. Transformational advertising is an in-

vitation to escape into a world that is necessarily subjective

and perceptual as well as necessarily intangible. It is the

transformational advertisings unique power to communi-

cate symbols and depict visual/verbal images that makes

the much valued intangibles understood. Transforma-

tional advertising has been employed effectively to com-

municate intangible and subjective benefits of

product/brand use. Therefore, it can achieve the same ef-

fects for communicating the subjective aspects of services

entailed in the episode strategies outlined earlier.

Proposition 6: Transformational advertising is an effec-

tive execution tool for the four episode strategies.

HOW TRANSFORMATIONAL ADVERTISING WORKS

What techniques does transformational advertising em-

ploy to make the intangible real? Consider the well-known

Michelin tire ad that shows a cute baby inside the tire ring

with the caption, When so much is riding on your tires.

The tire attribute being advertised here is safety. Michelin

promotes it by invoking the image of a loved one. Some

might consider this an example of intangible (safety) made

even more intangible (emotional arousal). And love for

ones loved ones and desire for their safety is as intangible

as it can get. Yet, there is nothing unreal about a babys cute

face, and there is nothing unfathomable or mentally impal-

pable about how a car accident due to an inferior tire can

take away ones loved ones. These feelings and images, al-

though invisible to the physical eye, are easily seen in the

minds eye (Pylyshyn 1973). They are made mentally

graspable by relating them to the consumers life experi-

ences. Most life experiences are intangible as wellorigi-

nally enjoyed holistically, relived in memory, seen by the

minds eye (rather than by the physical eye). It is by con-

necting an intangible product or service feature to the simi-

larly intangible life experience that the intangibles are

communicated intelligibly and understood naturally. They

are understood naturally in that the consumer is able to re-

late themto his or her own life, is able to vicariously place

himself or herself in the situation, and is able to feel the

immediacy of the intangible and subjective benefit be-

ing promoted. When this connection (between the service

benefit and the consumers life experience) is made

poorly, the intangible advertising fails. When it is done

skillfully, intangibility adds value rather than detracting

from it.

Intangible benefits belong, by definition, in a con-

sumers social and psychological worlds. A consumers

social world consists of his or her relationships with others

including the enjoyment of interpersonal exchanges and

the esteem in which others hold the consumer (cf. Levy

1959). The psychological world pertains to a consumers

self-concept and self-identity as well as to hedonic plea-

sure and/or experiential consumption (Holbrook and

Hirschman 1982; Sirgy 1982). Because subjective bene-

fits ultimately are experienced in the social and psycho-

logical worlds (Friedmann and Zimmer 1988), it is to these

experiences that the subjective aspects of service con-

tained in the episode messages ought to be linked.

The real challenge of service advertising, then, is how

to capture these subjective experiences effectively, that is,

how to execute subjective episodes effectively. To capture

subjective experiences effectively in advertising is tanta-

mount to making the ad (a) vivid or rich in detail, (b) realis-

tic, and (c) vicariously rewarding. Realistic here means

that the consumer views them as occurring in the world

surrounding him or her and accepts them as being within

his or her reach. Vicariously rewarding here means that the

life experience itself is substantial rather than trivial, is

positive rather than negative or neutral, and has a motiva-

tional attraction to it. For illustration, remembering ones

first day in college class is perhaps trivial for many stu-

dents; it is perhaps also neutral (if not negative) and most

likely has no motivational properties (i.e., it does not make

one want to re-live it). By contrast, remembering ones

first prom date is substantial, positive, and motivational;

consequently, it is vicariously rewarding.

Proposition 7a: Intangible service benefits can be com-

municated effectively by linking them to consum-

ers life experiences.

Proposition 7b: Life experience executions are effec-

tive when they are vivid, realistic, and vicariously

rewarding.

Proposition 7c: Life experience executions are vicari-

ously rewarding when they are nontrivial, positive,

and motivational.

Consider an actual ad for a luxury hotel. Its copy used

phrases such as orchestrating memorable conferences,

highest levels of personal service, architectural integ-

rity, and character and spirit of the surrounding area.

Mittal / ADVERTISING SERVICES 107

at SAGE Publications on May 20, 2009 http://jsr.sagepub.com Downloaded from

These phrases, and the service concepts they reflect, are

likely to lack any grounding in a typical consumers life

experiences. They make the intangible benefits even more

abstract, general, and mentally impalpable. By contrast,

consider the Amtrak ad (Exhibit 1) that visually and ver-

bally captures a life experience and does so vividly, realis-

tically, and in a vicariously rewarding way. Consider the

following copy in the ad: . . . That night, dinner in a dining

car with linen, china, and chefs. You hold hands under the

table. Could anyone blame you? The lights darken. A

movie is playing in the lounge. You watch the movie and

then the stars. . . . One can see in ones minds eye exactly

what the real experience will be, the experience appears

within the realm of possibility, and imagining oneself in it

already has begun to offer a vicariously rewarding experi-

ence. As employed in the Amtrak ad (Exhibit 1), transfor-

mational advertising is perhaps the most potent method of

capturing and conveying a life experience that subjective

service features or outcomes promise inanepisode strategy.

Proposition 8: By presenting the four episode strategies

as life experiences that are vivid, realistic, and vi-

cariously rewarding, transformational advertising

can execute them effectively.

SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION

A service product possesses both tangible and intangi-

ble attributes, but featuring tangible attributes in advertis-

ing does not substitute for intangible attributes, especially

if the core promise of the service brand resides in its intan-

gible aspects. Intangibility means, by definition, incorpo-

real existence. The latter is the intangibilitys defining

property. Four other properties that generally stem from

intangibility are abstractness, generality, nonsearchability,

and mental impalpability. This article has argued that these

properties can be overcome by using sound advertising

strategies, as summarized in Table 2.

Specifically, three groups of strategies have been de-

fined: physical representation, documentation, and epi-

sodes. This pool of strategies resembles the Berry and

Clark (1986) scheme with two enhancements. First, fur-

ther subgroups are identified in documentation and epi-

sode strategies. Specifically, documentation has three

subtypes (system, performance, and consumption docu-

mentation), and episode has four subtypes (consumption,

performance, process, and case history episodes). Second,

each strategy is linked to a property of intangibility for

which it is effective. It is from a contemplation of each

property, and of how the message would have to be pre-

sented to overcome that property, that a particular commu-

nication strategy is identified and given a name. The

resulting convergence (in broad terms) with Berry and

Clarks scheme signals compatibility with an important

essay in the literature.

Other essays in the literature also are congruent with

the present article. For example, George and Berrys

(1981) suggestion of stimulating word-of-mouth recom-

mendation is captured in the present strategy of consump-

tion documentation (i.e., user testimonials), and the

present performance episode invariably will feature ser-

vice employees, whomGeorge and Berry identify as a tar-

get audience. Similarly, Legg and Bakers (1987)

suggestion of using tangible cues, concrete language,

and/or dramatization parallels the physical representation,

documentation, and episode strategies, respectively, in the

present article. Furthermore, Legg and Bakers sugges-

tions of using behind-the-scenes operations and presenta-

tion of service scripts are broadly captured in the present

service process episode and case history process episode

strategies, respectively. Finally, Padgett and Allens

(1997) distinction of argumentation and narrative parallels

the present documentation and episode strategies, respec-

tively. But rather than reject argumentation in favor of the

narrative as Padgett and Allen do, the present framework

stipulates the utility of each; that is, argumentation is use-

ful and effective in documentation strategies, but its use

would be ill advised in episode strategies, which demand

the narrative style.

All cited authors emphasize vividness as a desirable

characteristic of communications about intangibles. Legg

and Bakers (1987) dramatization, Berry and Clarks

(1986) visualization, and Padgett and Allens (1997) nar-

ratives would demand, for their efficacy, vividness in pre-

sentation. This vividness (i.e., the quality of something

being real or lifelike) is a hallmark of a particular type of

advertising, namely, transformational advertising. Trans-

formational advertising is used for physical products to

communicate an intangible benefit of product use. Like-

wise, the present article argues that transformational ad-

vertising can be an effective advertising form to

implement the episode strategies whose goal is to trans-

form the abstract, general, and impalpable service attri-

butes into the concrete, specific, and palpable ones.

The strategies summarized in Table 2 are general prin-

ciples that link a specific property of intangibility to a spe-

cific advertising strategy. In the following section, the

foregoing framework is used to deduce a set of managerial

guidelines.

MANAGERIAL GUIDELINES

For years, academics have argued that services are in-

tangible and that advertising should attempt to make them

108 JOURNAL OF SERVICE RESEARCH / August 1999

at SAGE Publications on May 20, 2009 http://jsr.sagepub.com Downloaded from

tangible (Berry and Clark 1986; Hill and Gandhi 1992;

Turley and Kelley 1997). Service advertisers have heard it

loud and clear, or so it would seem.

Consider a print ad of a few years ago by Vanstar, a

communications network design company (since merged

into Inacom). In this particular ad, the company was trying

to promote the flexibility of its network system. Flexibility

is an intangible benefit, and the company tried to tangibal-

ize it by showing, in a side-by-side comparison, a stiff pair

of pants and a flexible pair of pants. Mission accom-

plished, or was it? Consider this: What business network

buyer does not know what network flexibility is? And if

there are any such buyers, would any of thembe helped by

this analogy with a pair of pants? Is this what is meant by

tangibalization? The analysis of intangibility in the pres-

ent article would suggest that intangibility is, by defini-

tion, incorporeal and that property cannot be undone by an

analogy with a corporeal object such as a pair of pants

and it need not be undone. Rather, it is the other properties

of intangibilityabstractness, generality, nonsearchabil-

ity, and impalpabilitythat can and must be overcome.

The tangibalization ploy in the Vanstar ad seems to be di-

rected at impalpability, but it fails to reduce impalpability,

that is, to explain what network flexibility means. One ef-

fective way in which to address impalpability, according to

the present article, would have been to employ a case his-

tory process episode approach (i.e., showing how Vanstar

delivered flexibility to a specific client), as suggested in

Proposition 5. With this example as a backdrop, a set of

managerial guidelines is outlined that stem from the theo-

retical propositions in this article.

Agood starting point for managerial guidelines is to an-

swer two interrelated questions: What is the goal of the

proposed advertising, and what aspect of service is to be

advertised? Although any list of goals is arbitrary, for pres-

ent purposes, possible goals are organized into three broad

categories: brand identity, brand positioning, and demand

creation. Likewise, possible aspects of service to feature in

advertising fall into three broad groups: inputs, processes,

and outcomes. Let us consider each goal in turn.

Brand Identity

Brand identity is an important and minimal goal of any

advertisement, and physical products often use a visual

image of the tangible product to create brand identity. For

intangible services, it is important to recognize that most

services do have certain tangible components, namely, the

service delivery systemthe physical facilities, materials,

and people. Featuring these tangible components in adver-

tising (an approach termed physical representation) cer-

tainly is an effective approach to tangibalizing the

otherwise intangible service product. But physical repre-

sentation can help brand identity only if the physical ele-

ment s shown are uni que i n vi sual appearance

(Propositions 1a and 1b). Thus, the brown UPS vans and

the yellow storefronts of Midas Mufflers car repair shops

serve to advance brand identity, whereas the look-alike

smiling faces of airline hostesses and the shots of swim-

ming pools or hotel lobbies do not. An extension of physi-

cal representation is the use of a distinct brand mark based

on an intrinsic element of the physical delivery system

(e.g., McDonalds golden arches), a physical object extrin-

sic to the service product (e.g., an umbrella for Travelers

Insurance), or a visual symbol (e.g., the Greek letter delta

for Delta Airlines); these also serve to advance the brand

identity. Many services, lacking such unique physical ele-

ments or symbols (e.g., many banks), are deprived of even

this simple tool.

Brand Positioning

Brand positioning entails defining the brands place in

the category, differentiating it from some or all competi-

tors (Ayer Press 1976). Service brands can position them-

selves by highlighting the differentiation on service

inputs, processes, or outcomes. First, consider differentia-

tion by inputs. The role of physical representation for

brand identity was discussed in the preceding paragraph.

Now, note that when physical elements of the service are

not unique (and will not help brand identity), they still can

help brand positioning by serving as cues to quality and/or

by building certain brand associations (Proposition 1b).

Physical representation sometimes can signal overall

quality such as plush hotel lobbies for first-class hotels and

tuxedoed waiters for upscale restaurants. Furthermore,

physical representation can create specific brand associa-

tions. For example, the casually attired crew members of

Southwest Airlines connote their informal and fun behav-

ior. Note, however, that only a limited number of brand as-

sociations can be built by physical representation; brand

associations that do not have a logical connection with any

of the physical elements of the service delivery system

cannot be advanced by the physical representation strat-

egy, as Proposition 1c states. To position a brand by asso-

ciations that have no connection with any physical

elements (e.g., network flexibility), one must look else-

where, as Propositions 2 to 8 suggest.

A second means of differentiating ones service is by

some differentiating feature(s) of ones service processes

such as speed, responsiveness, friendliness, failure-proof,

creative, or efficiency. All of these are intangibles. To

communicate them, service managers have a couple of

choices. First, if the process lends itself to some way of ob-

jective summarization, then the advertiser should present

objective data on process performance such as past punc-

Mittal / ADVERTISING SERVICES 109

at SAGE Publications on May 20, 2009 http://jsr.sagepub.com Downloaded from

tuality or safety record for an airline. This approach has

been termed performance documentation. Second, if the

process cannot be objectively summarized (e.g., respon-

siveness, friendliness), then the advertiser should depict a

representative service event characterized by that qual-

ity of the process (e.g., an example of responsive or

friendly service being delivered). This approach has been

termed performance episode.

A key difference between the documentation and epi-

sode strategies should be noted because sometimes the

service processes (or, for that matter, outcomes as well)

can lend themselves to either approach. Documentation

uses factual information and cites it in a descriptive copy

style. For this reason, its appeal is rational. By contrast,

episodes are events that occur in space and time, and they

are presented in visual and/or verbal narrative copy. For

this reason, they are capable of capturing and engendering

emotions. Agood example of this strategy is a recent ad by

Allstate Insurance (Exhibit 3). Here, the power of the per-

formance episode strategy is unmistakable. It effortlessly

overcomes all four undesirable properties of intangibility

of Allstates message.

Lastly, some service advertisers might seek to position

their brand by outcomes, that is, customer benefits of the

service. Sometimes, of course, service benefits are tangi-

ble (e.g., clean carpet from a cleaning service). Often,

however, service benefits can be intangible (e.g., peace of

mind from an insurance company). Essentially, these in-

tangible benefits can be communicated by depicting the

service consumer enjoying the benefits, that is, by employ-

ing what has been termed a service consumption episode

such as the one in the Amtrak ad (Exhibit 1).

Demand Creation

The final goal of service advertising can be demand

creation, both primary and secondarydemand for the

service category itself and demand for the specific service

brand, respectively (Belch and Belch, 1998, p. 18). Some

demand creation occurs, of course, by service positioning.

But often, demand is hampered because prospective cus-

tomers do not internalize the service benefits adequately

(i.e., the intangible benefits remain abstract, and prospec-

tive customers do not see the services salience and signifi-

cance to their lives personally [In what circumstances

would I need peace of mind?]), because they cannot

fathom what the service is (i.e., intangibility produces im-

palpability [What is network flexibility?]), or because

they do not know how to select the right service brand or

supplier (i.e., due to nonsearchability of the intangible

service [Which stockbroker is trustworthy?]). Abstract

service benefits and impalpable service features tend to

hinder the primary demand itself; nonsearchability hin-

ders selective demand or, correspondingly, postpones the

primary demand.

The messages aimed at demand creation tend to focus

on service outcomes, that is, service benefits that will ac-

crue to customers. Lacking tangibility, these benefits tend

to be abstract. If an ad were to simply state this benefit in a

descriptive copy (e.g., An Amtrak trip will let you relive

those romantic moments), then that would leave the in-

tangible service benefit quite abstract. The suggested solu-

tion, as Proposition 4 states, is to use a consumption

episode strategy, of which the previously described Am-

trak ad (Exhibit 1) is an excellent example. Likewise,

many service benefits, although not abstract, tend to be

general. Many service advertisements err by merely citing

these benefits in a descriptive ad copy (e.g., Our hotel will

do everything to satisfy you); instead, the suggested solu-

tion to overcome generality is to show the service com-

pany actually delivering those benefits to a specific client

(e.g., a dissatisfied hotel guest actually receiving a full re-

fund), that is, by employing a service performance epi-

sode, as suggested by Proposition 2b. Likewise, it is a mis-

taken practice to simply make performance/outcome

claims (e.g., Lose those unwanted pounds) without ac-

companying evidence to overcome nonsearchability in the

form of either performance documentation (Proposition

3a, e.g., the number of past clients who actually lost

weight) or consumption documentation (Proposition 3b,

e.g., featuring representative client testimonials). Finally,

when service outcomes are impalpable, rather than using

extraneous physical objects to drawan analogy, a case his-

tory approach (Proposition 5) is the effective solution, a

strategy exemplified by the Sprint ad described earlier

(Exhibit 2). Arelated example of the case history approach

is a snapshot of a representative event, a practice illus-

trated by the current print campaign for Hilton Hotels with

the theme It happens at the Hilton (Exhibit 4).

It may be clarified that the boundary between some pro-

cesses and outcomes is blurred. Auseful guideline is that a

behind-the-scenes activity usually is a clear example of

process. By contrast, for service activities performed in the

customers presence in which the customer is receiving the

benefit of the process instantaneously, the process also is,

fromthe customers perspective, outcome. The distinction

in such cases might lie in the message choice of whether to

depict the featured aspect of service from the service per-

formers or the customers vantage point. In either case,

the advertising strategy collectively calls on either docu-

mentation (when the process/outcome is objectively docu-

mentable) or episode strategies (when the process/

outcome is subjective). Arecent ad by Renaissance Hotels

offers a good example of documentation of service per-

formance by citing a J. D. Power and Associates Guest

Satisfaction Study ranking. The same ad, however, does

110 JOURNAL OF SERVICE RESEARCH / August 1999

at SAGE Publications on May 20, 2009 http://jsr.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Mittal / ADVERTISING SERVICES 111

EXHIBIT 3

at SAGE Publications on May 20, 2009 http://jsr.sagepub.com Downloaded from

EXHIBIT 4 1

1

2

a

t

S

A

G

E

P

u

b

l

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

s

o

n

M

a

y

2

0

,

2

0

0

9

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

j

s

r

.

s

a

g

e

p

u

b

.

c

o

m

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

not do as good a job of communicating another message

appeal it contains, namely, At Renaissance, hospitality is

king. This message demands, as Table 3 suggests, a per-

formance episode strategy. Instead, it relies on descriptive

body copy (as opposed to the narrative copy of an episode)

and, as if to tangibalize, on the photo of a famous king

(Henry VIII). These two elements do nothing to make

clear and vivid the otherwise impalpable, abstract, and

general service feature of kingly hospitality.

Consider, by contrast, a recent ad by Wyndham Hotels

(Exhibit 5). The ads selling appeal is the Wyndhamway,

which in this ad is translated as the hotel staffs readiness

to go the extra mile, so to speak. The ad conveys this effec-

tively by employing a performance episode strategy (as

Table 2 recommends). The Wyndhamway is an intangi-

ble service claim that is as abstract, general, and impalpa-

ble as it can get. Wyndham makes that differential

advantage concrete and palpable through a series of differ-

ent performance episodes.

These managerial guidelines are summarized in Table 3.

They represent merely an illustrative framework. Depend-

ing on what the advertising goal is and what service aspect

(input, process, or outcome) is entailed in that goal, a man-

ager should ask which specific property of intangibility is

potentially present in the chosen message. Each of the four

properties calls for a separate strategy, as the propositions

and resulting strategies summarized in Table 2 suggest.

These strategies do not depend on any tangible (i.e., physi-

cal) props. The idea of using tangible props such as physi-

cal objects unrelated to the core service to tangibalize an

intangible attribute is a misguided one. Vanstars pair of

pants, Arthur Andersens elephant, and Renaissance Ho-

tels king might well be judged creative and even success-

ful in achieving other goals (or these ads other elements

might well achieve still other goals), but so far as tackling

intangibility is concerned, their attempt at tangibalization

seems artificial and forced. This is because they attempt to

use as props the corporeal objects that are at best tangen-

tially related to the service benefits. (Arthur Andersens

more recent global best practices print campaign pru-

dently uses tangible visuals that are directly relevant to the

service, e.g., a pizza delivery boy as an example of best de-

livery service practice). The incorporeal existence is an in-

escapable property of intangible messages; it cannot and

need not be undone. What needs to be tackled are the other

four properties of intangibility, and the tangible images of

a pair of pants, an elephant, and a king do nothing to over-

come those. By contrast, the ads by Amtrak, Wyndham

Mittal / ADVERTISING SERVICES 113

TABLE 3

Managerial Guidelines for Service Advertisers

Advertising Goals Suggested Strategy Description/Illustration

Brand identity Physical representation:

Service system Show unique visuals of service system (e.g., UPSs brown vans)

Brand mark Show unique symbols associated with the service brand (e.g.,

McDonalds golden arches)

Brand positioning

By differentiation on:

Inputs Physical representation Even if not unique, show visuals of service system that might

signal quality and/or other associations (e.g., show casual/friendly

crew of Southwest Airlines to position it as a fun airline)

Processes Performance documentation Cite objective data on past performance (e.g., past punctuality of

airline: 98%)

Performance episode Depict the story of a typical performance incident (e.g., how an

insurance agent delivered superior service in a particular instance)

Outcome Service consumption episode Show vivid images of customers enjoying the service (e.g., cruise

passengers enjoying leisure time)

Demand creation

By service outcome

To make the outcome less:

Abstract Service consumption episode Present vivid vignettes of customers realizing the benefit (e.g., a mature

couple having a romantic time on Amtrak)

General Service performance episode Present specific past incident of service delivering the benefit (e.g., a

hotel guest reporting a specific dissatisfaction received a full refund)

Nonsearchable Service consumption documentation Present a testimonial from a satisfied customer (e.g., a plastic surgery

recipient showcasing his or her postsurgery face)

Impalpable Service case history episode Document and present a past case of how the firm offered service to a

specific client (e.g., the Sprint ad, the Wyndham Hotels ad)

at SAGE Publications on May 20, 2009 http://jsr.sagepub.com Downloaded from

114 JOURNAL OF SERVICE RESEARCH / August 1999

EXHIBIT 5

at SAGE Publications on May 20, 2009 http://jsr.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Hotels, Sprint, Hilton Hotels, and Allstate Insurance strive

to make the intangible service claims concrete, specific,

searchable, and/or palpable.

CONCLUSION

Past literature cites intangibility as the principal source

of challenge for service advertising. The real challenge, in-

stead, is one of choosing a message strategy. Intangibility,

defined as incorporeal existence, does not hurt service ad-

vertising. What hurts are unthoughtful message strategies

(e.g., basing the message on tangible components of the

service delivery system just to avoid the challenge of han-

dling the intangible), ill-conceived creative executions

(e.g., relying merely on descriptive copy without docu-

mentation so that it accentuates generality and abstract-

ness), and failure to embed intangible service performances

or outcomes in realistic consumer life experience epi-

sodes. Whereas most services have some tangible compo-

nents, their differentiating appeal might well lie in some

intangible aspect of service process or outcome. There is

no need to shirk from using such intangible appeals. In-

deed, handling intangibility is advertisings special talent.

Transformational advertising has countless times elevated

mere mortal products into the realm of incorporeal, intan-

gible, psychosocial life experiences. There is no denying

that conveyingintangible features or benefits of the service

is a challenging task. But that is a challenge substantially

tackled by a careful analysis of the nature of intangibility

(i.e., which quality a specific intangible message claim

has) and then choosing a matching advertising strategy as

identified here. In the services literature, principles or

guidelines for advertising are but few. It is hoped that the

propositions advanced here will stimulate a discourse,

among managers and researchers alike, on this important

topic.

REFERENCES

Aaker, David A. (1991), ManagingBrandEquity. NewYork: Free Press.

and Douglas M. Stayman (1992), Implementing the Concept of

Transformational Advertising, Psychology & Marketing, 9 (May-

June), 237-53.

Ayer Press (1976), Ayers Dictionary of Advertising Terms. Philadelphia:

Ayer Press.

Belch, George E. and Michael A. Belch (1998), Advertising and Promo-

tion: An Integrated Marketing Communications Perspective, 4th ed.

Boston: Irwin/McGraw-Hill.

Berry, Leonard L. (1980), Services Marketing Is Different, Business,

30 (May-June), 24-29.

and Terry Clark (1986), Four Ways to Make Services More Tan-

gible, Business, 36 (October-December), 53-54.

and A. Parasuraman (1991), Marketing Services: Competing

through Quality. New York: Free Press.

Bitner, Mary Jo (1992), Servicescapes: The Impact of Physical Sur-

roundings on Customers and Employees, Journal of Marketing, 56

(April), 57-71.

, William T. Faranda, Amy R. Hubbert, and Valarie Zeithaml

(1996), Quality and Productivity in Service Experiences: Custom-

ers Roles, in Advancing Service Quality: A Global Perspective, Bo

Edvardsson, Stephen W. Brown, Robert Johnston, and Eberhard E.

Scheuing, eds. NewYork: St. Johns University, International Service

Quality Association, 289-98.

, , , and (1997), Customer Contributions

and Roles in Service Delivery, International Journal of Service In-

dustry Management, 8 (3), 193-205.

Breivik, Einer and Sigurd Villads Troye (1996), Dimensions of Intangi-

bility and Their Impact on Product Evaluations, Developments in

Marketing Science, vol. 19, E. Wilson and J. Hair, eds. Miami, FL:

Academy of Marketing Science, 56-59.

Darby, M. R. and E. Karni (1973), Free Competition and the Optimal

Amount of Fraud, Journal of LawandEconomics, 16(April), 67-88.

Day, Ellen (1992), Conveying Service Quality through Advertising,

Journal of Services Marketing, 6 (Fall), 53-61.

Deighton, John (1994), Managing Services When the Service Is a Per-

formance, in Service Quality: New Directions in Theory and Re-

search, Roland T. Rust and Richard L. Oliver, eds. Thousand Oaks,

CA: Sage, 123-38.

Fisk, Raymond P. (1981), Toward a Consumption/Evaluation Process

Model for Services, in Marketing of Services, J. H. Donnelly and W. R.

George, eds. Chicago: American Marketing Association, 191-95.

Friedmann, Roberto and Mary R. Zimmer (1988), The Role of Psycho-

logical Meaning in Advertising, Journal of Advertising, 17 (1),

31-40.

George, William R. and Leonard L. Berry (1981), Guidelines for the

Advertising of Services, Business Horizons, 24 (July-August),

52-56.

Grove, Steven J., Gregory M. Pickett, and David N. LaBand (1995), An

Empirical Examination of Factual Information Content among Ser-

vice Advertisements, Service Industries Journal, 15(April), 216-33.

Hill, Donna J. and Nimish Gandhi (1992), Services Advertising: A