Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jirtwe

Uploaded by

Kailash SreeneevasinOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jirtwe

Uploaded by

Kailash SreeneevasinCopyright:

Available Formats

In the popular imaginary, war is thought of as two gigantic armies clashing in titanic tests of

strength. World Wars One and Two are, in essence, what constitutes the intuitive sense of war. And yet,

for at least three decades, such conflicts have become anachronisms. The 1973 Yom Kippur War saw the

last major tank battle and the Iran-Iraq War of the Eighties was the last total war. Interstate wars not to

mention total wars are obsolete as an organizing dynamic in the capitalist world-system.

Contemporary wars have instead been couched in terms of humanitarian interventions to

protect vulnerable populations, rogue state interdictions or counterinsurgencies. That is, wars which are

not wars but take place between states or multilateral coalitions against nonstate actors or rogue states

declared criminal. Of these two, Im interested in armed conflict against non-state actors because I think

it typifies war in modern capitalism. It is not that the politics of rogue states is unimportant but rather

(1) post-intervention insurgencies tend to be much more important than the actual fight against rogue

states armies which are beaten relatively quickly (2) Projecting into the future, Western militaries

especially American military has turned away from interventionism toward drone warfare and the kinds

of combat that Im interested in.

In order to understand the logic of war, we must look at the combatants and battlefields of

modern war constituted by the class subjectivities of modern capitalism. In particular I want to isolate

the emergence of a globalized bourgeoisie as against a ghettoized surplus population. It is this latter

population which forms not only the cadre and political legitimacy of various insurgent groups but is

ultimately the object of managerial violence and policing.

First, I will look at the global bourgeoisie. Accounts of the rise of the bourgeoisie that has

escaped national boundaries is associated with the transnational capitalist class literature found in the

works of Leslie Sklair, William Robinson and others. While I agree with many of their claims regarding

the importance of trade and FDI flows, multinational production and especially the hegemony of finance

capitalism, I not only do not want to cover old ground but find their neo-Gramscian accounts to devolve

too much into class voluntarism. Instead, I want to provide a macro-history in which capitalism emerges

as a global social totality. While capitalism spread as a world-system during the industrial revolution and

arguably before, it did so through exchange and market relations. It is only in course of the 20

th

century

that social basis of production transforms globally and capital remakes the world in its own image.

The subsumption of society occurs earliest in nineteenth century Britain and America but

generalizes in 20

th

century Europe during postwar reconstruction when bourgeois hegemony totalizes.

Stalinist modernization was a powerful lever of primitive accumulation for a predominantly peasant

state and the Red Army extended state capitalist development into Eastern Europe. The final part of the

story is postcolonial independence since import-substitution modernization was the postcolonial states

attempt at transforming their societies into bourgeois capitalist societies proper. After World War II,

there were three main historical configuration of capitalism- Atlantic Fordism, Stalinism and Third World

developmentalism- all united by the logic of capital.

This was, however, not yet a world in which hegemonic rivalry had been superseded at a global

or regional level since neither Stalinist states nor Third World states had their societies subsumed by

capitalism but were rather in the transition. In the Soviet Union, the bureaucracy the role that an

organic bourgeoisie would have and the Third World was experiencing in the twentieth century its own

bourgeois revolution. And, I think it is in the stage of the transition to capitalism that hegemonic

rivalry is important either because (1) the bourgeoisie achieves dominance without hegemony and the

resultant alliances with pre-capitalist classes and centralized state-forms might translate to aggressive

foreign policies such as the Prussian Junker classes before World War I (2) leading states fall behind in

competition with new developers leading to imperialism or military balancing in order to recoup losses

such as 19

th

century Britain vis--vis Germany after the formers industrial base declined (3) societies

under the whip of external necessity to transform their production process engage in alliance behavior

in order to survive the military-geopolitical and economic pressures of advanced capitalist powers. An

example that James Allinson writes about is Hashemite Jordan. (4) states such as Israel where the

military is the only functioning institution for modernization leading to a state in which capitalism occurs

under the logic of war-driven accumulation.

The crisis of the 1970s began to transform this situation outside Europe. Land reform,

industrialization and importantly the turn to export-driven economic development led to dominance

WITH hegemony for the bourgeoisie in the ex-colonies. Increasingly, hegemonic rivalry became obsolete

and replaced by states committed to delivering high growth rates and political stability. But, I end in

1991 for a very important reason. While I think dtente and economic stagnation in the Soviet Union

effectively ended its battle for hegemony, there was still competition and proxy wars between the USSR

and the US in the eighties namely in Afghanistan. Furthermore, geopolitics in the colonies was in

transition from classical interstate rivalry into a world where armed combat is dominated by non-state

insurgents. So, India and Pakistan fight their last true war in 1971 but in 1986 India stages one of its

largest military mobilizations to which Pakistan responds. Camp David effectively ends the Arab-Israeli

conflict as a rivalry for dominance of the Middle East-North African regional system; however, the

Lebanese Civil War stands as a transition whereby Syria and Israel engage in combat but the real stakes

of that conflict are about decapitating the PLO and it is clear that Syria does not truly desire hegemony

except insofar as it can politically control Lebanon. It was the collapse of the USSR that marks the

political integration of the world into the capitalist international order by the Soviet bloc and it truly

pacifies postcolonial geopolitics by disqualifying a superpower patron.

Regardless, the result of the process whereby capital remakes society in its image has been the

pacification of rivalry over military and/or political leadership over a regional or global system even if

not geopolitical conflict in the form of policy incompatibilities. Instead, there has been a tendency

toward bilateral or multilateral treaties, densely interconnected institutions or security arrangements

military alliances, joint-defense pacts. At worst, there is a cold peace because formalized settlement is

domestically unviable or a cease-fire enforced by peacekeepers. All this has been led by the financial

and military power of the American state which is the most powerful state in the system of capitalist

states.

Ahh.. but poor capitalism it generalizes itself not through its prowess but crisis and it is out of

the logic of crisis that a more positive account of armed conflict in capitalism begins. The postwar

Bretton Woods systems initially saw the promotion of a liberal order in which trade and production

internationalization was associated with high rates of growth in all industrializing countries. The US ran

balance of payments deficits designed to stimulate the international economy and massive technology

transfers were given the Western European and East Asian states considered the frontline in the

defense against communism. Beginning in the mid-1960s, Western Europe and Japan completed their

economic recoveries saturating their internal markets which forced them to look to export markets to

sustain growth. The subsequent rise in worldwide competition led to a crisis whereby the global

economy became wracked by persistent overcapacity which it could not shake out. Despite

financialization of the economy and a reduction in the share of income going to labor, the rate of profit

has generally failed to recover in excess of the previous rate (outside a brief boom in the 1990s) instead

creating a trend toward higher unemployment or wage stagnation.

Overcapacity in manufacturing has underwritten system-wide deindustrialization. The latter

began in the US in the 1970s before generalizing in the 1980s and 1990s. Neoliberal reform hollowed

out industrial manufacturing as a share of GDP replaced by employment in the service sector and

informal economy. Deindustrialization has not been restricted to the core industrialized countries of the

West but even those countries considered industrializing whereby peak employment rates have been

proportionally smaller to those achieve by the early industrializers. Deindustrialization has been the

outcome of industrys very dynamism as labor-saving accumulations have thrown people out of the

formal sector creating a world in which, to quote Jan Breman, labor almost disappears from sight in a

landscape dominated by capital.

The subjectivity of these populations has variously been conceived of as the precariat or

immaterial labor but instead I will utilize Marxs concept of consolidated surplus population in Chapter

25 of Volume 1 and Im influenced by its interpretation by Aaron Benanav in Endnotes journal. Chapter

25 is initially an account of the determinations of the wage rate. Marx shows how the maintenance of a

level of employment keeps wages in line with the needs of accumulation. The industrial reserve army of

unemployed contractsa s the demand for labor rises causing wages to rise. Rising wages cut into

profitability causing accumulation to slow down. As demand for labor falls, the reserve army grows and

wage gains evaporate. However, if the industrial army regulates the labor market, the unemployed

increasingly outgrow this function reasserting themselves as absolutely redundant to the valorization

process. The dynamic growth of capitalism tends to throw off labor without it being absorbed back into

new industries. These populations are not completely outside capitalist social relations. Capital might

not need these workers, but they still need to work. They are thus thrust into abject forms of wage

slavery. This crisis expresses the fundamental contradiction of the capitalist mode of production. On the

one hand, it reduces people to workers. On the other hand, they cannot be workers since, by working,

they undermine the possibility of their reproduction as workers.

The general law has been taken up and abandoned as the immiseration thesis. It was held that

Marxs prediction of rising unemployment and immiseration had been contradicted by capitalisms

history. After Marxs death, the industrial working class both grew in size and saw its living standards

rise. The rise of new industries that were simultaneously labor- and capital-absorbent did put off the

decline of Marxs secular trajectory for more than half a century. Currently, surplus capital in money

markets masks some of the tendency toward absolute immiseration through working class debt and by

preventing the bottom from falling out on global aggregate demand. And yet, debt has not stopped

wage moderation or rising unemployment. Informal employment constitutes half to three-quarters of all

non-agricultural employment in the low-GDP countries and is increasing as a share of employment in

high GDP countries. Microelectronics or informational technologies have been unable to absorb labor in

replacement of industrial decline and indeed multiply the problem by making industrial production

more efficient. The industrial proletariat is increasingly a small share of the overall workforce. To quote

Jan Breman again: a point of no return is reached when a reserve army waiting to be incorporated into

the labor process becomes stigmatize as a permanently redundant mass, an excessive burden that

cannot be include now or in the future, in economy and society. This metamorphosis is, in my opinion at

least, the real crisis of world capitalism.

The logic of surplus population and the logic of warfare interact at least at three levels: First,

class relations underpin the cadres and political legitimacy for many insurgent groups. Economic

privatization has allowed the stoking of and fomenting of local antagonisms and the recruitment of the

unemployed especially the youth by warring parties as for example in various sub-Saharan African

conflicts. In India, the 2004 renaissance of the Naxalite rebellion emerges as peasants are threatened

with displacement from the countryside by giant hydro, logging and mining projects. The endangered

peasants form the core fighting strength of the rebllion. A more specifically urban context is Hezbollah.

Starting in the 1960s, the predominantly Shia peasantry were displaced and urbanized. The initial

reaction to rising poverty among the newly minted Shia urban poor were not along sectarian lines as

the Communist Party held influence along with the moderate Islamist Party Amal. During the mid-1970s,

the Lebanese economy declined as the 1975 Civil War negatively affected output and investment and

the Israeli invasion in 1982 further depressed the economy leading to deep recession in 1983-1984.

Furthermore, Israeli intervention in 1978 reinvigorated the Shia movement of the deprived and the

Amal party began fighting the PLO to defend the nation. However, Israels 1982 invasion cemented the

perception among the Shia poor that neither the Left nor moderate Islamism could defend their

interests. This is the condition under which Hezbollah declares itself to the world in 1985 and why it has

strong popular support among the Lebanese working class and urban poor.

The second interaction is warfare accelerating the process of creating surplus populations

through internally displaced peoples and refugees. Im thinking in particular of modern settler-

colonialism particularly Gaza where liberalization of the Israeli economy was met by the post-First

Intifada decoupling of Palestinian labor and what Sara Roy calls the de-development of Gaza. We see

the consequences today in which, since 2005, Gazans have been left to starve such that the UN predicts

it will be literally uninhabitable by 2020. Note, settler-colonialism deflects to a certain extent my

argument while simultaneously bringing it to a similar place because we cannot say that it is the

impersonal logic of the market that is operating here but the hellfire and brimstone of occupation.

The third connection is urbanization because the process of creating surplus populations is

primarily an urban process. The application of capital-intensive techniques to agriculture and saturation

of export markets for agricultural goods have forced a large-scale migration of the peasantry while

increased productivity in industry has displaced them from manufacture leaving them to languish in

slums and ghettoes. Those populations are considered chaotic threats in urban enclaves who must be

policed and managed. Hence, an antagonism between the metropole and the slum emerges leading to a

situation in which shanty settlements are bulldozed by government planners, paramilitaries go into

favelas to clear them for modern infrastructure or real estate development, to address the purported

threat of disease or crime or, as in the case of Brazil and the Olympics, to just make these people

disappear. Gaza has been constructed out of city-scale refugee camps and the war in Afghanistan has

underwritten mass flight into the cities. The future of warfare lies, according to former Major Ralph

Peters, in the streets, sewers, high-rise buildings, industrial parks, and the sprawl of houses, shacks,

shelters that form the broken cities of our world.

1

In Peters account, it is not only Hezbollah in Beirut

or the Somali National Alliance in Mogadishu, but protestors in Los Angeles who are among the dramatis

personae of modern warfare. Warfare operates as a kind of accumulation through spatial

transformation- the subsumption of space through militarization.

Accumulation of wealth at one pole is, at the same time, the accumulation of misery, agony of

toil, slavery, ignorance, brutality, mental degradation at the opposite pole i.e. on the side of the class

that produces its own product in the form of capital. The world-historic emergence of capitalism has

ended the era of war-driven rivalry between capitalist states without thereby ushering in an era of

perpetual peace as liberals so long for. Instead, the explosion of a surplus population in slums, favelas,

banlieues and ghettoes constitute a threatening mass which must be policed and managed to ensure

stability. Here, then, are the conditions of the possibility for the emergence of the figure of the insurgent

and the counterinsurgent who typify war in the neoliberal period. I want to, at the end, risk hyperbole. It

seems to me that this form of warfare is the capitalist form of warfare proper. The wars we saw

between capitalist states or between capitalism and its outside was violence of a world order in statu

nascendi. It is not the warfare between capitalists but rather between capitalists and the poor to

manage them either through impersonal coercion or outright brute force which is truly the geopolitics

of force within the bourgeois mode of production.

1

Ralph Peters, Our Soldiers, Their Cities, Paramenters, Spring 1991, pp. 43-50,

You might also like

- Kailash Revised Plan of I DissertationDocument2 pagesKailash Revised Plan of I DissertationKailash SreeneevasinNo ratings yet

- Kailash Srinivasan Political Theory ListDocument2 pagesKailash Srinivasan Political Theory ListKailash SreeneevasinNo ratings yet

- Bird - On The Poverty of TheoryDocument14 pagesBird - On The Poverty of TheoryKailash SreeneevasinNo ratings yet

- Descriptive StatisticsDocument5 pagesDescriptive StatisticsKailash SreeneevasinNo ratings yet

- PowerM AuditSocietyRitualsVerification 1997 p1-14 I68890382 OcrDocument17 pagesPowerM AuditSocietyRitualsVerification 1997 p1-14 I68890382 OcrKailash SreeneevasinNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Human Rights: Fall 2014 Prof. Inés Valdez Session 9: Critiques of RightsDocument18 pagesIntroduction To Human Rights: Fall 2014 Prof. Inés Valdez Session 9: Critiques of RightsKailash SreeneevasinNo ratings yet

- Russian PeasantryDocument20 pagesRussian PeasantryKailash SreeneevasinNo ratings yet

- 2013 Warfare State Kellogg Preprint LibreDocument30 pages2013 Warfare State Kellogg Preprint LibreKailash SreeneevasinNo ratings yet

- PowerM AuditSocietyRitualsVerification 1997 p1-14 I68890382 OcrDocument17 pagesPowerM AuditSocietyRitualsVerification 1997 p1-14 I68890382 OcrKailash SreeneevasinNo ratings yet

- Descriptive StatisticsDocument5 pagesDescriptive StatisticsKailash SreeneevasinNo ratings yet

- Russian PeasantryDocument20 pagesRussian PeasantryKailash SreeneevasinNo ratings yet

- Wendt Response Paper Systems Evolution ThouhtDocument5 pagesWendt Response Paper Systems Evolution ThouhtKailash SreeneevasinNo ratings yet

- Caverley HegemonyDocument17 pagesCaverley HegemonyKailash SreeneevasinNo ratings yet

- Kailash Srinivasan Quant Sequence 1 10/29/13 58)Document2 pagesKailash Srinivasan Quant Sequence 1 10/29/13 58)Kailash SreeneevasinNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- DFMA Lab 1Document13 pagesDFMA Lab 1roshni muthaNo ratings yet

- Job Desc - Packaging Dev. SpecialistDocument2 pagesJob Desc - Packaging Dev. SpecialistAmirCysers100% (1)

- Tugas 5Document17 pagesTugas 5Syafiq RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Bank StatementDocument1 pageBank StatementLatoya WilsonNo ratings yet

- Introduction To HRM (Supplementary Note) : (Type Text)Document11 pagesIntroduction To HRM (Supplementary Note) : (Type Text)Gajaba GunawardenaNo ratings yet

- Homework 5 - Gabriella Caryn Nanda - 1906285320Document9 pagesHomework 5 - Gabriella Caryn Nanda - 1906285320Cyril HadrianNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Financial Statements Project: GUL AHMAD Textile MillsDocument32 pagesAnalysis of Financial Statements Project: GUL AHMAD Textile MillsHanzala AsifNo ratings yet

- Presented by Gaurav Pathak Nisheeth Pandey Prateek Goel Sagar Shah Shubhi Gupta SushantDocument17 pagesPresented by Gaurav Pathak Nisheeth Pandey Prateek Goel Sagar Shah Shubhi Gupta SushantSagar ShahNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Adoption of Electronic Banking System in Ethiopian Banking IndustryDocument17 pagesFactors Affecting Adoption of Electronic Banking System in Ethiopian Banking IndustryaleneNo ratings yet

- BUS 1103 Learning Journal Unit 1Document2 pagesBUS 1103 Learning Journal Unit 1talk2tomaNo ratings yet

- Accountancy: Class: XiDocument8 pagesAccountancy: Class: XiSanskarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 Process ApproachDocument12 pagesChapter 7 Process Approachloyd smithNo ratings yet

- Scholarship Application 2024 1Document3 pagesScholarship Application 2024 1Abeera KhanNo ratings yet

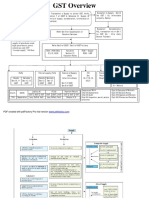

- GST OverviewDocument17 pagesGST Overviewprince2venkatNo ratings yet

- Creating Value in Service EconomyDocument34 pagesCreating Value in Service EconomyAzeem100% (1)

- Varun MotorsDocument81 pagesVarun MotorsRohit Yadav86% (7)

- Benifits Iso99901Document6 pagesBenifits Iso99901Jesa FyhNo ratings yet

- An Agile Organization in A Disruptive EnvironmentDocument14 pagesAn Agile Organization in A Disruptive EnvironmentPreetham ReddyNo ratings yet

- Ias 40 Icab AnswersDocument4 pagesIas 40 Icab AnswersMonirul Islam MoniirrNo ratings yet

- Cephas Thesis FinalDocument53 pagesCephas Thesis FinalEze Ukaegbu100% (1)

- EfasDocument2 pagesEfasapi-282412620100% (1)

- CH IndiaPost - Final Project ReportDocument14 pagesCH IndiaPost - Final Project ReportKANIKA GORAYANo ratings yet

- Live Case Study - Lssues For AnalysisDocument4 pagesLive Case Study - Lssues For AnalysisNhan PhNo ratings yet

- Government AccountsDocument36 pagesGovernment AccountskunalNo ratings yet

- Rural MarketingDocument40 pagesRural MarketingBARKHA TILWANINo ratings yet

- Govt ch3Document21 pagesGovt ch3Belay MekonenNo ratings yet

- SOP Guidelines For AustraliaDocument1 pageSOP Guidelines For AustraliaShivam ChadhaNo ratings yet

- FMCG Sales Territory ReportDocument21 pagesFMCG Sales Territory ReportSyed Rehan Ahmed100% (3)

- Marketing Plan For Ready-Made Canned Foo PDFDocument10 pagesMarketing Plan For Ready-Made Canned Foo PDFHussain0% (1)