Professional Documents

Culture Documents

What Forces Determine Whether A Country Can Maintain Its Debt GDP Ratio at Some Sustainable Level

Uploaded by

Zainorin AliOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

What Forces Determine Whether A Country Can Maintain Its Debt GDP Ratio at Some Sustainable Level

Uploaded by

Zainorin AliCopyright:

Available Formats

What forces determine whether a country can maintain its debt GDP ratio at some

sustainable level.

How would a rise in real interest rates affect a countrys international debt and its debt

GDP ratio. What would a nation have to do to maintain its debt GDP ratio under these

conditions? Use the Iceland case study to illustrate your answers.

Americans may remember that at the start of the 2008 financial crisis, Iceland literally went

bankrupt. The reasons were mentioned only in passing, and since then, this little-known

member of the uropean !nion fell back into obli"ion.#

In 200$ Iceland%s debt was e&ual to 200 times its '(), but in 200*, it was +00 percent. The

2008 world financial crisis was the coup de grace. To set this straight, Iceland%s debt ,as in The

-entral .ank/ was e&ual to 0*1 of the '2) in 200$ and fell to 3$1 of the '2) in 200*,

according to 4orld .ank 5and 2ata6arket7 statistics. In 200+, that percentage reached 8031.

(ow, if by Iceland the author meant Iceland%s banks, then it%s true that the banks% debt was

pretty big9astronomical really9and by 200*, Iceland%s banks did in fact reach + times the

'2), though that%s '2) not '().

Then there%s this: ;The three main Icelandic banks, <andbanki, =apthing and 'litnir, went belly

up and were nationali>ed, while the =roner lost 801 of its "alue with respect to the uro. At the

end of the year Iceland declared bankruptcy.# Again the statement, ;At the end of the year

Iceland declared bankruptcy# is wrong. And the Icelandic kr?nur lost more like 001 of its "alue

compared to the uro any way you look at it. ;-ontrary to what could be e@pected, the crisis

resulted in Icelanders reco"ering their so"ereign rights, through a process of direct participatory

democracy that e"entually led to a new -onstitution. .ut only after much pain.#

Then it says: ;'eir Aaarde, the )rime 6inister of a Bocial 2emocratic coalition go"ernment,

negotiated a two million one hundred thousand dollar loan, to which the (ordic countries added

another two and a half million. .ut the foreign financial community pressured Iceland to impose

drastic measures. The C6I and the uropean !nion wanted to take o"er its debt, claiming this

was the only way for the country to pay back Aolland and 'reat .ritain, who had promised to

reimburse their citi>ens.#

The constituent%s meetings are streamed on-line, and citi>ens can send their comments and

suggestions, witnessing the document as it takes shape. The constitution that e"entually

emerges from this participatory democratic process will be submitted to parliament for appro"al

after the ne@t elections.#

8

Defusing to bow to foreign interests, that small country stated loud and clear that the people are

so"ereign.#

Cirst of all, it%s nai"e to think that Iceland was able to stand up to the I6C. 4ith the I6C pro"iding

emergency currency support, it has had influence in di"erting Icelandic resources back toward

the financial sector. If Iceland had refused to share the I6CEs world"iew, it could ha"e been

denied funds necessary to implement capital controls and stop the =ronaEs tailspin. Cailure to

adhere to the I6CEs demands could ha"e also caused IcelandEs so"ereign credit rating to drop

significantly, which could ha"e isolated Iceland from international capital markets ,despite the

fact that credit ratings agencies, in the wake of 2008, are in need of urgent reform/.#

4hether or not influenced by the I6C, one might note that two of the three banks that Iceland

;let fail# because it couldn%t bail them out ,they were nine times the country%s '2)/, ha"e been

re-pri"atised and there is currently a debate about pri"atising the third. (ot to mention, there%s

the case of AB Frka, in which +8 percent of a publically owned geothermal energy company

was sold to -anadian company 6agma nergy ,now called GAlterra )ower%/, gi"ing it access to

geothermal energy in the DeykHanesbIr peninsula for J0 years with a renewal option for

another J0. Curthermore, while Iceland may seem like a symbol of sticking it to the financial

institutions that brought about the financial collapse, the people really ha"en%t escaped the

burden. According to an F-2 report Iceland has put more money into its failed financial

institutions than any other country e@cept Ireland. Bo in this way Iceland is not a model9the

people in Bpain need not wa"e Icelandic flags.In some places Iceland is held up as being a

model of how to sur"i"e an economic crisis and rebuild society. Cor most Icelanders this seems

totally wrong.

Q5. What forces determine whether a country can maintain its debtGDP ratio at some

sustainable level?

2

How would a rise in real interest rates affect a country!s international debt and its

debtGDP ratio? What would a nation have to do to maintain its debtGDP ratio under

these conditions? Use the Iceland case study to illustrate your answers.

Take, for example, a country such as Iceland in 1999. The medium term sustainability of the debt

of the country was highly unlikely and the country looked like it was insolvent. The explosive

growth of Icelandic firms has been financed by aggressive borrowings by Icelands three largest

banks and the total external debt of the economy is now more than times !"#, i.e. the

economy is highly leveraged. The negative debt position is partially explained by investment in

new power plant capacity, the rapid expansion of Icelandic firms abroad, high levels of outward

$"I, young population, consumer spending and, perhaps, misleading accounting.

In any case, it seems clear that the global credit crunch hit Iceland at a vulnerable time. Icelandic

banks, consumers and firms are suddenly faced with a falling currency and prohibitively high

borrowing costs. "oubts have been cast on the governments ability to support the Icelandic

banks, simply due to the fact that the combined balance sheets of the three largest banks were

%%&' of !"# at the end of ())&. The vulnerabilities of maintaining an independent monetary

policy have also become clear and debate has been vigorous on how to better defend the

currency or, alternatively, to adopt a stronger currency. !overnment officials point to a debt*free

government, healthy banks and a flexible economy as key buffers, but recession seems likely.

If foreign +public debt is very high, the market will price the probability that the debt may not be

serviced in full and in time. In this case, the level of interest rates and interest spreads on the debt

will reflect the possibility that ,partial default may occur. -uch as risk of default implies that the

risk*ad.usted interest rate on the debt will be higher than under no default risk and higher interest

rate will trigger a more rapid accumulation over time of a given stock of debt. -uch an increase

in spread may trigger a perverse debt dynamics in which, if the country tries to service its debt in

full at current high spreads, debt ratios grow even if the country+government is following policies

that are sound. -uch preserve dynamics becomes a serious issue for countries that are in a crisis

and being borderline between being insolvent and illi/uid. 0s there is broad uncertainty about

whether there is insolvency, markets will react to any increase in the ob.ective probability of

default by increasing the spreads on the country+government debt and thus worsening the debt

dynamics of the country+government. 0n otherwise solvent agent may thus be thrown in an

insolvency region if real interest rates on the debt become too high.

Currency Policy

Icelands currency remained strong during the countrys pre*crisis expansionary period in spite

of its enormous current*account deficit because of the large inflow of foreign funds. 1ith the

collapse of the banking system, that inflow stopped and the krona went into free fall. The decline

intensified the countrys economic problems. 2any households and businesses held foreign*

currency indexed debts that exploded in domestic cost. 0s noted above, the government worked

to minimi3e the economic harm from this development by forcing banks to restructure their loans

in domestic currency.

$

Icelands currency policy also includes the use of strict capital controls which make most

transnational capital movements illegal. These controls have blocked an estimated 4% billion,

roughly e/ual to ) percent of Icelands !"#, from leaving the country. 5ad the government not

taken action, the resulting outflow would no doubt have led to a complete currency meltdown.

Thanks to the controls, the krona, although lightly traded, soon strengthened and then stabili3ed.

Housing Policy

The government took strong steps to minimi3e the threat to household finances caused by the

collapse of the housing bubble and to restore stability to the housing market.

The government then introduced several new initiatives designed to provide more long term

relief. These lowered household debt and mortgage interest payments as well as provided support

for housing alternatives and renters. $or example, the government first pursued a strategy of

encouraging householders to directly negotiate write*downs with their lenders, often with the

assistance of an ombudsman. !iven the slow progress, the government introduced a debt*

forgiveness plan that wrote down underwater mortgages to 11) percent of a households assets.

To ensure that working people were the main beneficiaries of the plan, the amount of relief was

tied to the value of a modest house and family si3e. 2ore detailed financial examinations were

available for households in especially serious financial trouble, with the possibility of greater

write*downs.

Social Policy

The Icelandic government faced a serious fiscal challenge as a result of the crisis, with its budget

deficit rising to 16. percent of !"# in ())9. Impressively, it reduced overall spending and the

deficit to (.6 percent of !"# in ()11 while simultaneously strengthening key social programs.

$or example, the government increased unemployment benefits over the years ())& to ()1) and

also lengthened the period during which workers could receive unemployment benefits from

three to four years. In addition it significantly boosted the means*tested social assistance

allowance and the minimum pension benefit.

7ver the same period, the government also increased subsidies for mortgage interest payments

by 1)%.1 percent, far outstripping the 8).9 percent increase in mortgage costs. This increase

raised the average household subsidy for interest costs from approximately 16 percent to ()

percent of the total interest cost. 2oreover, the interest rebates were largely targeted at working*

class households, which meant :that about a third of the interest cost of lower and average

income households was paid by the government in ()1).;

3

You might also like

- Safety and Health Officer (SHO), Workplace Assignment WPA Paper 4 - HIRARC, NIOSH Malaysia.Document24 pagesSafety and Health Officer (SHO), Workplace Assignment WPA Paper 4 - HIRARC, NIOSH Malaysia.Zainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Good Negotiation Skills Can Give Your Career A BoostDocument2 pagesGood Negotiation Skills Can Give Your Career A BoostZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Safety and Health Officer (SHO), Workplace Assignment WPA Paper 4 - HIRARC, NIOSH Malaysia.Document24 pagesSafety and Health Officer (SHO), Workplace Assignment WPA Paper 4 - HIRARC, NIOSH Malaysia.Zainorin AliNo ratings yet

- HAZARD IDENTIFICATION RISK ASSESSMENT AND RISK CONTROL (HIRARC/HIRADC) Office HAZARD For Building SampleDocument10 pagesHAZARD IDENTIFICATION RISK ASSESSMENT AND RISK CONTROL (HIRARC/HIRADC) Office HAZARD For Building SampleZainorin Ali75% (36)

- How To Ask For A Pay Rise and Get A BonusDocument4 pagesHow To Ask For A Pay Rise and Get A BonusZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Factories and Machinery Act 1967 (FMA 1967) - Safety Related RegulationsDocument59 pagesFactories and Machinery Act 1967 (FMA 1967) - Safety Related RegulationsZainorin Ali87% (31)

- 33 Soalan Bocor Utk VIVADocument2 pages33 Soalan Bocor Utk VIVAZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Safety and Health Officer (SHO), Workplace Assignment WPA Paper 4 - HIRARC, NIOSH Malaysia.Document24 pagesSafety and Health Officer (SHO), Workplace Assignment WPA Paper 4 - HIRARC, NIOSH Malaysia.Zainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Safety and Health Officer (SHO), Workplace Assignment WPA Paper 4 - HIRARC, NIOSH Malaysia.Document24 pagesSafety and Health Officer (SHO), Workplace Assignment WPA Paper 4 - HIRARC, NIOSH Malaysia.Zainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Factories and Machinery Act 1967 (FMA 1967)Document24 pagesFactories and Machinery Act 1967 (FMA 1967)Zainorin Ali75% (4)

- Safety and Health Committee OSHA 1994. Safety and Health Officer SHO Malaysia. Mesyuarat Jawatankuasa Keselamatan Dan Kesihatan Pekerjaan. JKKP 1996Document25 pagesSafety and Health Committee OSHA 1994. Safety and Health Officer SHO Malaysia. Mesyuarat Jawatankuasa Keselamatan Dan Kesihatan Pekerjaan. JKKP 1996Zainorin Ali100% (8)

- Building Malaysia As An Islamic Finance HubDocument2 pagesBuilding Malaysia As An Islamic Finance HubZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Ergonomic and Manual HandlingDocument117 pagesErgonomic and Manual HandlingZainorin Ali100% (1)

- Under The Factories and Machinery Act 1967: Health RegulationsDocument43 pagesUnder The Factories and Machinery Act 1967: Health RegulationsZainorin Ali86% (7)

- Knowing Yourself BetterDocument2 pagesKnowing Yourself BetterZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- The Mark of A Good LeaderDocument3 pagesThe Mark of A Good LeaderZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Ways To Improve Your Interpersonal SkillsDocument2 pagesTop 10 Ways To Improve Your Interpersonal SkillsZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Valuing Women LeadersDocument4 pagesValuing Women LeadersZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Ways To Impress A Potential EmployerDocument10 pagesTop 10 Ways To Impress A Potential EmployerZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Ways To Maximise Social Media Impact For Your BusinessDocument2 pagesTop 10 Ways To Maximise Social Media Impact For Your BusinessZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of A Successful EntrepreneurDocument6 pagesCharacteristics of A Successful EntrepreneurZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Most Common Resume Mistakes That Could Cost You The JobDocument2 pagesTop 10 Most Common Resume Mistakes That Could Cost You The JobZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Ways To Combat StressDocument5 pagesTop 10 Ways To Combat StressZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Reasons Why Talents QUITDocument2 pagesTop 10 Reasons Why Talents QUITZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- 20 Good Work Habits To DevelopDocument2 pages20 Good Work Habits To DevelopZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Discuss The Product Cycle Theory As An Explanation For Why Comparative Advantage in Knowledge Intensive Products Shifts RapidlyDocument1 pageDiscuss The Product Cycle Theory As An Explanation For Why Comparative Advantage in Knowledge Intensive Products Shifts RapidlyZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Scarce Resources Will Be Consumed, and The World's Climate Will Continue To ChangeDocument2 pagesScarce Resources Will Be Consumed, and The World's Climate Will Continue To ChangeZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Suppose That AFTA(ASEAN Free Trade Area) is Expanded to Include China. This Will Increase Both Malaysian Imports of Land-Intensive and Labor-Intensive China’s Products and China’s Imports of Capital-Intensive Malaysian ProductsDocument3 pagesSuppose That AFTA(ASEAN Free Trade Area) is Expanded to Include China. This Will Increase Both Malaysian Imports of Land-Intensive and Labor-Intensive China’s Products and China’s Imports of Capital-Intensive Malaysian ProductsZainorin AliNo ratings yet

- The Global Economic Crisis Has Shattered Two Articles of Faith in Standard Economic Theory That Human Beings Usually Make Rational Decisions and That the Markets Invisible Hand Serves as a Trustworthy Corrective to Imbalance.Document6 pagesThe Global Economic Crisis Has Shattered Two Articles of Faith in Standard Economic Theory That Human Beings Usually Make Rational Decisions and That the Markets Invisible Hand Serves as a Trustworthy Corrective to Imbalance.Zainorin AliNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Residual Valuations & Development AppraisalsDocument16 pagesResidual Valuations & Development Appraisalscky20252838100% (1)

- Retail IndustryDocument3 pagesRetail IndustryakavinashkillerNo ratings yet

- Calculate employee wagesDocument29 pagesCalculate employee wagesPrashanth IyerNo ratings yet

- A Case For Economic Democracy by Gary Dorrien - Tikkun Magazine PDFDocument7 pagesA Case For Economic Democracy by Gary Dorrien - Tikkun Magazine PDFMegan Jane JohnsonNo ratings yet

- A Critically Compassionate ApproaDocument16 pagesA Critically Compassionate ApproaAna MariaNo ratings yet

- Guruswamy Kandaswami Memo A.y-202-23Document2 pagesGuruswamy Kandaswami Memo A.y-202-23S.NATARAJANNo ratings yet

- Citi Bank Kpi Summary 2021-2022Document5 pagesCiti Bank Kpi Summary 2021-2022tusharjaipur7No ratings yet

- ACCT4010 Group Assignment SolutionsDocument3 pagesACCT4010 Group Assignment SolutionsSin TungNo ratings yet

- Rajpur Garments and Textiles Limited: Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad IIMA/F&A0400Document4 pagesRajpur Garments and Textiles Limited: Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad IIMA/F&A04002073 - Ajay Pratap Singh BhatiNo ratings yet

- Hexaware TechnologiesDocument2 pagesHexaware Technologieshsolanke21No ratings yet

- Intercompany transactions elimination for consolidated financial statementsDocument13 pagesIntercompany transactions elimination for consolidated financial statementsicadeliciafebNo ratings yet

- Online BankingDocument38 pagesOnline BankingROSHNI AZAMNo ratings yet

- Berlin School Final Exam - Financial Accounting and MerchandisingDocument17 pagesBerlin School Final Exam - Financial Accounting and MerchandisingNarjes DehkordiNo ratings yet

- Practie-Test-For-Econ-121-Final-Exam 1Document1 pagePractie-Test-For-Econ-121-Final-Exam 1mehdi karamiNo ratings yet

- AgreementDocument16 pagesAgreementarun_cool816No ratings yet

- ACCT203 LeaseDocument4 pagesACCT203 LeaseSweet Emme100% (1)

- Finance A Ethics Enron Hyacynthia KesumaDocument1 pageFinance A Ethics Enron Hyacynthia KesumaCynthia KesumaNo ratings yet

- ICE Cotton BrochureDocument6 pagesICE Cotton BrochureAmeya PagnisNo ratings yet

- Calm Finance Unit PlanDocument7 pagesCalm Finance Unit Planapi-331006019No ratings yet

- Exclusive Investment Cheat Sheet: The Ultimate Wealth Creation SummitDocument14 pagesExclusive Investment Cheat Sheet: The Ultimate Wealth Creation SummitMohammad Samiullah100% (1)

- Public Expert - Trend IndicatorsDocument21 pagesPublic Expert - Trend Indicatorsrayan comp100% (1)

- 822 Taxation XI PDFDocument181 pages822 Taxation XI PDFPiyush GargNo ratings yet

- Final Exam/2: Multiple ChoiceDocument4 pagesFinal Exam/2: Multiple ChoiceJing SongNo ratings yet

- Solutions To End-of-Chapter Three ProblemsDocument13 pagesSolutions To End-of-Chapter Three ProblemsAn HoàiNo ratings yet

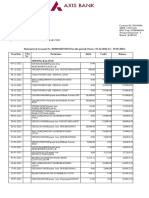

- Garima Axis Bank SDocument3 pagesGarima Axis Bank SSajan Sharma100% (1)

- Biz Cafe Operations Excel - Assignment - UIDDocument3 pagesBiz Cafe Operations Excel - Assignment - UIDJenna AgeebNo ratings yet

- Risk Management Options and DerivativesDocument13 pagesRisk Management Options and DerivativesAbdu0% (1)

- Mergers Acquisitions and Other Restructuring Activities 7th Edition Depamphilis Test BankDocument19 pagesMergers Acquisitions and Other Restructuring Activities 7th Edition Depamphilis Test Banksinapateprear4k100% (33)

- Coursebook Answers: Answers To Test Yourself QuestionsDocument5 pagesCoursebook Answers: Answers To Test Yourself QuestionsDonatien Oulaii85% (20)

- ACCT 1115 - Final Review SolutionsDocument13 pagesACCT 1115 - Final Review SolutionsMarcelo BorgesNo ratings yet