Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Green Paper On Housing Policy: Hong Kong SAR

Uploaded by

KB Borthwick0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

177 views28 pagesAnalysis of market conditions and subsequent review of policy decisions with recommendations.

Original Title

Green Paper on Housing Policy : Hong Kong SAR

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentAnalysis of market conditions and subsequent review of policy decisions with recommendations.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

177 views28 pagesGreen Paper On Housing Policy: Hong Kong SAR

Uploaded by

KB BorthwickAnalysis of market conditions and subsequent review of policy decisions with recommendations.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 28

Green Paper on Housing Policy

The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

Kyle Bryce-Borthwick REAL/BEPP 236

The Wharton School

7 May 2014

Executive Summary

The Hong Kong property market faces a critical imbalance between demand

and supply whilst affordability worsens to critical levels;

As of yet, existing measures have been inadequate:

To combat this, the Government has introduced extensive cooling measures on the

demand-side (Further Measures), and such measures have been successful in curbing

further price growth. However such measures, including substantial hikes in ad

valorem stamp duty targeting specific market actions, are inadequate as a sustainable

long-term solution. Volumes of sales have plummeted and affordability has worsened

as transaction costs have increased substantially and access to credit has weakened.

A supply-led strategy should be adopted:

The response to the imbalance should instead be supply-led, with new unit construction

increasing the balance of public assisted housing over market produced outcomes. To

further this, the Home Ownership Scheme should be reinstated in tandem with

increased deliverance of Public Rental Housing to achieve a target ratio of 60:40 in

government assisted to private market units. On a material level, such would include

the introduction of 250,000 assisted-ownership new units over the next decade, or an

addition of 0.89% annually to total housing stock. Around 200,000, or around 0.7%

additional stock annually, should be added to PRH stock over the next decade. In the

private sector, steady supply of new land as well as the easing of restrictive zoning

policies, should be implemented to add on another 300,000 to 400,000 over the next

decade. In total, present government estimates should be revised from an inadequate

1.77% annualized increase in stock to around 3% in additional stock annually until

2025.

Severe market inelasticity is a long-term concern:

To this end, the Government should expand increased infrastructure development in a

tailored, specific manner that will meaningfully lead to multi-primate outcomes

addressing issues of severe market inelasticity. Long-term demand for property,

although difficult to predict, is healthy whilst present issues of critical unaffordability

harm Hong Kongs development as a financial, technological, and educational

powerhouse. Given Hong Kongs unique regulatory and governance framework, its

institutional strengths and strategic location embedded into Chinas economic

heartland, regional competition remains limited and demand for property development

will continue to increase substantially.

The Governments multifaceted role is rare and conflicting;

The Governments role as a de facto monopolist in the real estate industry is unique

both across sectors and by international standards. Resultantly, the government faces a

tradeoff between keeping prices high as a means of extracting revenue (resultantly,

keeping other forms of taxation low) and ensuring the general public has access to

affordable housing. Existing policy provides for the lowest 30% of households through

Public Rental Housing and another 20% through previous assisted ownership schemes,

while the private market caters for around 30% of households. Consequently,

suggested government policy should address the remaining 20% who are not catered

for by either mechanism, the sandwich class, as well as future generations who may

not be grandfathered into existing units.

Government Priorities

In developing a comprehensive housing policy, the Government has explicitly

focused on two primary objectives (i) housing affordability and (ii) maintaining a

healthy and financially stable real estate market that may lean against cycles and

withstand heavy external shocks. The existence of a third objective, however, is much

accounted for in public policy but seldom unexplained in official discourse. The Hong

Kong property market is unique in its role a key pillar in the territorys economy.

Stamp duty and auction proceeds additionally comprise a substantial proportion of

around 25 30% of total Government revenues (Appendix I). Measures that may

destabilize long-term transaction volumes and price levels could eradicate a significant

source of government revenue that would otherwise have to be compensated by

increased taxation on personal income and profits.

The real-estate market structure is highly concentrated with a small number of

developers controlling the market, a situation comparably unique in an international

perspective. The territorys density, high prices and size of developments, however,

require substantial economies of scale that present challenges to more traditional,

localized structures present in other markets. With this in mind, the small number of

market participants and high market concentration make the market particularly

vulnerable to anticompetitive practices. Developers may choose to withhold stock and

act in a visible, coordinated manner whilst narrowly skirting regulations against such

practices. The recent sizeable fall in transaction volume accompanied oddly with

modest rises in price levels indicates a situation where such practices may have had

adverse effects on affordability despite the imposition of cooling measures.

The State of the Market

Housing prices in Hong Kong are by all measures, one of, if not the highest in

the world. Prices per square meter in the residential sector are estimated to be $20,660,

second only to Monaco and first among world cities. In the 2012 edition of the Knight

Frank Global Index measuring house price change, Hong Kong not only topped 55

housing markets but also accounted for the fastest pace of price growth since Q3 2008

(Knight Frank 2012). By 2013, however, Government instituted cooling measures had

led to a drop to 17

th

place only a 7.7% rise compared to previous years 23.6%

(Knight Frank 2013). This does tell the whole story. Transactions in the next quarter

following the imposition of the measures dropped 67%, falling below even 2008

levels. Annualized figures account for the highest drop in 10 years, surpassing

recorded drops for even the Eurozone, Banking and SARS Crises. Despite the 48.6%

drop in transactions, price levels still increased by a substantial 7.7% and occupancy

costs remain the worlds highest. In a 2013 Survey by Savills, relocation costs

(measuring residential and office costs) for 14 employees were the highest in Hong

Kong for the fourth consecutive year, topping other world-cities such as New York and

London (Savills). Retail and office rents are similarly world beating, with two Hong

Kong districts accounting for positions 1 and 4 in the office market respectively as well

as Hong Kong holding a substantial lead over New York as the most expensive retail

property market overall (Appendixes III and IV ). Across all market segments, there is

a severe market imbalance between demand and supply. This is not simply a problem

specific to housing or housing finance, but an imbalance present across all sectors of

the industry.

Prices in the private market, however, do not carry across to all segments of

society. Former Chief Executive Donald Tsang noted that around 50% live in

government subsidized housingthe housing issue is not one that is [endemic] to the

disadvantaged groups (Long Term Housing Strategy). The sandwich class, those

who earn more than that allowed by government housing but not enough to withstand

high prices within the housing sector, constitute the most affected segment of society

by persistently high prices. Government priorities in housing have been driven by a

desire to minimize intervention within the market as well as promote the fair and stable

development of the private market. Nonetheless, affordability is still a critical issue for

first-time buyers. House prices remain the worlds most unaffordable at almost 15

times higher than the Median Annual Income, more than three times higher than the

multiple given for Singapore a regime with similar supply characteristics

(Demographia). The territory, however, does have a relatively high owner-occupancy

rate at 52% but below government targets of 70%. This figure is particularly

interesting given that around 30% of housing units are Public Rental Units, leaving

around 20% potentially comprising the sandwich-class who are not catered for by

the market and government policy.

Access to housing is not the only concern of policy makers and the general

public; the investment characteristics of property are of particular significant to

methods of wealth transfer and accumulation in a territory characterized by high

private savings rates

1

. The question of fairness applies more in the mind of equal

treatment across society by the government than of equal outcomes enjoyed by Hong

Kong residents. The Government has consistently maintained its policy of positive

non-interventionism espousing minimum intervention in the private sector whilst

materially safeguarding only the needs of the most needy.

Government Assisted Housing Policy

Public rental housing (PRH) constitutes the lionshare of government assisted

housing- comprising some 30% of total supply of housing units. The provision of

assistance to those with genuine housing needs has always been the heart of the

Governments housing policy. As at 31 March 2013, about 2.09 million people (about

30% of the population) lived in PRH flats. The PRH stock was about 766,300 units.

1

Gross savings (% of GDP) 28% in 2012, 30% - 32% in the years prior. Source: The World Bank

The Government intends to continue to assist low-income families who cannot

afford private rental accommodation through PRH. The target is to keep the average

waiting time for Waiting List general applicants at around three years. As of March

2013, there were about 116,900 general applications and 111,500 non-elderly one-

person applicants under the Quota and Points System on the Waiting List for PRH. The

average waiting time for PRH general applicants is around 2.7 years.

The Government has implemented the following requirements when assessing

the genuine need of PRH recipients:

- A Waiting List is operated for the allocation of new or refurbished PRH flats to eligible

applicants in accordance with the order of registration;

- Non-elderly one-person applicants are subject to the Quota and Points System, under which

points will be assigned to them based on their age when the applications are registered,

whether they are PRH tenants and their waiting time. The more points the applicant scores, the

earlier the applicant will be offered a flat, subject to the fulfilment of all the PRH eligibility

criteria;

- To be eligible, applicants and their family members must undergo comprehensive means tests

covering both income and assets, and must not own or co-own or have an interest in any

domestic property in Hong Kong or have entered into any agreement ot purchase any domestic

property in Hong Kong or hold more than 50% of shares in a company which owns, directly or

through its subsidiaries, any domestic property in Hong Kong. At the time of allocation, at least

half of the family members included in the application must have lived in Hong Kong for seven

years and all family members must be still living in Hong Kong;

- Public rental tenancies cannot be passed on automatically from one generation to the next.

When a tenant passes away, a new authorised person (other than the surviving spouse) is

subject to a comprehensive means test; and

- Long-term tenants (i.e. those who have stayed in public rental housing for 10 or more years)

with income and assets exceeding prescribed limits are required to pay additional rent or

vacate their flats.

(Housing Factsheet)

It is a long-established policy of the Housing Authority to set PRH rents at

relatively affordable levels. As per the Housing Ordinance, the Housing Authority

conducts reviews of rents biannually and adjusts all-inclusive PRH rents according to

the changes in the overall household income of PRH. As of March 2013, PRH rent

ranged from $290 to HK$3,880, whilst the average rent was about HK$1,540 per

month a relatively small percentage of income earned by qualifying classes.

The Housing Authority originally implemented the policy as a relief measure from

the effects of the 1953 Shek Kip Mei fire which had left 50,000 squatter-dwelling

residents homeless. At the time, the territory had been facing massive waves of

immigration from the then newly established Peoples Republic of China, and

resultantly, settlement by these refugees-turned-residents was haphazard informal.

Government policy stemmed from a need to replace inadequate housing with

formalized forms in a way that did not increase the burden of housing on this low-

income sector of society significantly.

Today, whilst still maintaining the objective to target inadequate housing, the

rationale of the Housing Authority has developed as a means to also target specific,

disadvantaged groups (i.e. the elderly, families) whilst maintaining incentive structures

for working population to continue to better themselves. Contributions are capped vary

with means but are capped at 15%, limiting wage pressures on the lower end of the

income spectrum in the territory. Strangely enough, the Government has maintained its

longstanding free-market policies by intervening in the market to safeguard the interest

of the grassroots mitigating the impact it has as a monopolist.

Overview of Subsidized Home Ownership

Whilst issues of informality and inadequate housing had largely been addressed

with the imposition of PRH, the sandwich class of those who did not qualify for

PRH and also are not adequately catered for by the private market comprise a second

area necessitating government policy. Government targets were set to increase

homeownership from relatively low levels of around 30% in the late 1970s to an

optimistic 70%. To meet this demand, the Government pursued a policy of acting as

the developer for this segment of the market.

Since 1978, about 467 800 (as at March 2013) subsidized flats have been sold

to low- to-middle income households at discounted prices under the various subsidized

home ownership schemes, including the Home Ownership Scheme (HOS), the Private

Sector Participation Scheme (PSPS) and the Tenants Purchase Scheme (TPS)

introduced by the Housing Authority, as well as the Flat-For-Sale Scheme and

Sandwich Class Housing Scheme of the HKHS. Such schemes provided relatively

affordable housing with discounts set at around 30 40% under market conditions.

Owner-occupancy ratios increased substantially since policy implementation,

reaching 53% by the policys sunset period in 2002. However, substantial debate had

centered on the relevance and fairness of such a policy considering some households

only temporarily qualified for such benefits and was able to resell their properties for

substantial profit. Additionally, price shocks following the 1998 and 2001 crashes

depressed property values to a state where affordability was no longer a prime issue in

the minds of the general public. Subsequently in 2002, the Government decided to end

assisted ownership policies and a permanent moratorium on the Home Ownership

Scheme was instituted:

Under the repositioned subsidised housing policy in 2002, the objectives of the

Governments housing policy are to provide public rental housing (PRH) to low-

income families who cannot afford private rental housing, withdraw from playing

the role of a property developer, cease the production and sale of subsidised sale

flats, and minimise intervening in the market. Encouraging the public to purchase

homes is no longer an objective of the Governments housing policy

(Relaunching of Home Ownership Scheme)

The Government held the view that increasing homeownership rates to the

target of 70% was no longer paramount if the public sector had to play as the

developer and intervene substantially in the market where prices and profits of

property developer had become substantially depressed compared to previous periods.

Yet in 2012, in response to substantial increases in price levels partnered with

severely deteriorating levels of affordability, the incoming government led by CY

Leung reexamined subsidized home ownership policies. Planning objectives were set

to provide some 17 000 new HOS flats over the four years from 2016/17 onwards, and

thereafter an annual average of 5 000 HOS flats. It is expected that the first batch of

about 2 100 new HOS units will be completed in 2016/17, and the pre- sale will take

place in end-2014.

Demand continues to increase;

Population growth in Hong Kong has largely been stable over the past ten

years, remaining below 1%. Recent data indicates growth in population to be 1.17%, a

much lower figure than in Singapore but higher than that in China as a whole.

Immigration can be broken down into (1) One-way entry permits issued to Mainland

Chinese (2) Targeted immigration available through the General Employment Scheme,

Capital Investment Scheme and other initiatives.

The volume of One-way entry permits has remained constant since 1997

capped at 150 daily or 54,750 annually. At 62% of total migration, one-way permits

comprise the majority of immigration flows into Hong Kong. Such inflows usually

represent family reunions or cases of marriage in a way that does not alter natural

household formation substantially, particularly as such inflows act as a substitute for

the territorys birthrate of 0.9 per woman the lowest such figure worldwide.

Consequently, the stability and substitutability this source of immigration exerts does

not pose extraneous consequences for demand levels within the market sector.

Immigration under schemes intended to attract talent has risen substantially, the

large bulk from the General Employment Scheme (28,625 admitted in 2012, or 0.4%

of total population). Net outflows remain small, generating a net gain of around 0.3%.

It is not only the volume of migration entering into the territory that may affect demand

in the private market, but the quality and specific demands characteristic of it. Foreign

professionals who comprise the bulk of net migration into Hong Kong tend to have

smaller households (1-2 persons) and demand larger spaces than that is commonplace

for Hong Kong locals. Such will have an outsized footprint in expansions of demand in

the territory.

Non-local buyers account for a third source of demand for properties. In 2011,

19.5% of transactions for new properties and 6.8% in the second-hand market were

from foreign (primarily Mainland Chinese) buyers.

The effect of Mainland Chinese buyers has had an outsized impact on the Hong

Kong real estate market. In Q3 2011, PRC buyers made up 53.9% of all new sales by

value. However, after the suspension of eligibility for residency status by property

acquisition, this figure declined to 31.2% by Q3 2012. Further measures, including the

imposition of a special stamp duty on non-permanent Hong Kong residents, led to a

decline in this proportion to around 6% by the second quarter of 2013. However, the

special stamp duty and other recent cooling measures are only temporary. Speculative

and second-home demand in the territory will continue to persist in the long-run. Such

demand has only been diverted to second-choice markets other than Hong Kong and

Singapore, leading to substantial rises in property prices in Sydney and London due to

substantial increases in transactions from Mainland buyers following the imposition of

cooling measures.

Supply is severely restrained;

The natural geography has severely limited the extent which supply can

operate. The city has a mountainous terrain with most of the land remaining free from

development. Subsequently, Over 40% of the territory is protected under the Country

Parks Ordinance whilst a further 20% remains undeveloped. The land that is developed

has taken to extreme rates of density, with Hong Kong home to 2,354 buildings over

100 meters more than triple the next highest, New York at 725 (CBTUH).

Nonetheless, Hong Kong can become increasingly innovative at looking at

constructing even taller buildings and rezoning areas where buildings are capped at

certain heights. Substantial maneuvering exists on this end of the spectrum, as zoning

has been uneven across the territory and building regulations overly strict considering

the critical imbalance between demand and supply. Prices in the territory are incredibly

high and nonetheless, could support the financial health of increasingly innovative

solutions to the supply problem.

As of present, the Government allocates the bulk of its land by which it offers

to the housing market through auctions. In the long term, however, this method will not

appropriately address the housing crisis. Land auction phase out small developers and

encourage high prices as means of distributing costs of the land back to the

Government. With this strategy, the government has curtailed the proliferation of

smaller developers stimying competition in a sector that requires much greater

oversight. Hong Kong developers are disproportionately represented amongst the

worlds largest, with players Sun Hung Kai, Henderson Land, New World

Development, Hang Lung Group and Wheelock all possessing a market capitalization

over $5 billion (Forbes). This situation raises questions as to whether developers are

abnormally large and enjoy an oligopolistic market structure in a sector that is

traditionally more localized and more competitive.

Anticompetitive practices have proliferated with regards to the real estate

market. The territory has been target of a slew of scandals, including the 2011 39

Conduit Road in which Henderson Land lied about sales in order to push up prices.

However the most jarring of scandals has been one involving the co-chairmen of Sun

Hung Kai properties who are currently undergoing trial for indirect payments made to

high profile government figures with regards to land auctions (Yung). Such actions

suggest market malpractice and that further competition and regulation in this sector is

needed in order to best accommodate and fair and healthy real estate sector. The

government should perhaps look into expanding the use of tenders and involving non-

price considerations in land allocation policies moving away from traditional land

auctions.

The Government has entered the market insofar that it has operated the Urban

Renewal Authority. Such measures, however, need to be expanded and targeted at

regions with particularly exacerbated issues of affordability. Older areas across Eastern

and Central Kowloon still require substantial redevelopment, with removal of

substandard tenement housing an issue that requires substantial government

intervention. The Government, in this case, can take the role as market leader in

adopting innovative practices that may lead to better prices. For example, split-market

developments where buildings are divided amongst affordable, market and luxury

portions has yet to proliferate in the Hong Kong market despite its popularity in other

regions, notably in the United States.

The largest such measure the Government should intervene is the further

expansion of infrastructure networks as well as proper use of existing infrastructure

developments that will lead to multi-primate outcomes within the city ultimately

increasing sorely-needed elasticity. The development of North Lantau, in tandem with

the construction of the HK-Zhuhai-Macau link and improvement of existing the

Airport link, is capable of providing 200,000 -300,000 new units that may relieve

pressure from the city center. These road and rail connections, however, need to be

carefully completed with an explicit emphasis on time reduction. The Government

should nto be afraid of using through-train or express services to outer regions, cutting

commute time, even if it does cannibalize price growth in more centrally located

precincts.

A last suggestion targeting increased supply is to build up retail centers across

the edge of Hong Kongs northern land border with the Mainland. Developments at

Lok Ma Chau and Lo Wu could act to absorb demand specific to the substantial

number of day-trippers, a source of some 28 million users of Hong Kong malls

annually. These measures would not only cater to demand, but also reduce congestion

and undue pressure on primarily residential areas of the city (Wong)

Financing is largely adequate in the private market;

Presently, the current system of mortgage financing is largely robust and

affordable. Interest rates are low and the small number of banks competes heavily by

lowering lending rates further. In addition, Hong Kong has one of the most developed

mortage markets in the region with a participation rate of 47% (Hofinet?).

However, the Governments recent use of financing as method to curb demand

(see Appendix II) has been ineffective and unfair in addressing price growth. One of

the most significant sources of demand has been the purchase of second-homes

through cash only instruments. Reducing access to credit most severely affects first-

time buyers and members of the sandwich class. As such, it is recommended that the

Government restore LTV ratios from 70 to 80% - whilst maintaining existing

restrictions on properties valued over HK$10 million. The territorys present low

delinquency ratios partnered with small number of robust banks may lend the market

well to restore 90% LTV specifically targeting first time buyers with good credit

scores. However such measures must be compliant Basel III Capital Rules, and the

feasibility of such a policy should be examined.

The interest spread is also relatively high (see Appendix VII) considering low

delinquency rates encountered by mortgage banks. Recent competition through the

underpricing of lending rates is perhaps a natural development to the sector. Bank

profitability is not a concern in the territory, however anti-competitive strategies are.

The market has been supported by a rigorous regulatory framework learned lessons

learned from 1998 Asian Financial Crisis. The territory has a proven track record

showing that is able to sustain future shocks. However, caution should be given

considering how dependent Hong Kong is on the international economic environment.

Specifically, the US Dollar peg makes the territory particularly dependent to actions

undertaken by the Federal Reserve.

Real estate plays an outsized role in the territory;

Hong Kong is unique in that the real Estate industry comprises a substantial

pillar in the territorys economy. Although the sector has traditionally seen as a

cronyist sector, helping secure Hong Kongs 1

st

place in The Economists Crony

Capitalism Index, this does not do the industry justice in terms of the role and

innovation the industry has played in territorys economy. Notably, the Value Capture

Model by which the Hong Kong Metro uses increased property prices as means of

subsidizing itself has gained international praise ( ). The use of mixed-use

developments is also notable, particularly as cities in Mainland Chinese embrace the

same strategies Hong Kong has in improving accessibility and dealing with severe

shortages of space. The real estate market also benefits from being highly liquid with

good accounting and legal practices inherited from the UK jurisdiction

Yet with all that being said, the sector is prone to anti-competitive practices that

may have reduced efficiency in the market. In addition, around 25 35% of public

finances is dependent on revenue from the real estate market. It is clear that the

government is dependent on the property markets ability to maintain its health in order

to keep taxation through forms low. As a result, Hong Kong has maintained

competiveness through low profits and income taxation supported by high property

prices.

On the flip side, this precise dynamic also threatens Hong Kong development

as an international hub of innovation and commerce. Occupancy costs have become

exorbitantly high, exceeding even London and New York. Figures show that costs to

locate to Hong Kong are 60% higher than they are in Singapore, a territory which has

been able to have more elastic stock benefiting its development in sectors ancillary to

finance. Hong Kong (As well as Singapore) face difficulty in that industries cannot

simply move to the suburbs or to nearby centers but still enjoy similar benefits in

which businesses located in the center may achieve. The regulatory framework and tax

regime that have made Hong Kong so successful extend only to its borders and cannot

be compensated in quite the same way as is the case in other centers should

development on the Mainland occur. This phenomenon threatens attempts to diversity

the regions economy, and thus skews development unnaturally in favour of industries

that can withstand Hong Kongs high costs, notably finance. Creative industries will

find it particularly difficult to survive in a market where costs are so high. Similarly,

the Governments interest in positioning Hong Kong as a hub for innovation and tech-

based start-ups may only surmount to token gestures with no real opportunity for

natural development.

Ultimately, however, the greatest concern is the role in which high prices

continue to lead to tremendous issues of unaffordability. Similarly, Hong Kong

residents cannot be expected to move out to the suburbs or to another city. This

market is simply not just another city in China or Asia for that matter, and cannot be

easily replaced by another location for Hong Kongs residents. Housing provision in

Hong Kong particularly necessitates a social function. While government has been

successful in catering for the lower end of the market, ensuring the development of a

robust and fair mortgage sector, and developing effective infrastructure in promoting

multi-primate centers, affordability in the private sector is severely limited. As the

most unaffordable market in the world by some margin (see Appendix V), the

Government needs to cater for the sandwich class as well as future generations who

are not grandfathered into existing units.

Concluding Remarks and Policy Recommendations

Hong Kong is an exceedingly fascinating case of a world city, akin to New

York and London, but one that encounters definite, regulatory limits to its territory

rendering its market as severely supply inelastic. Despite the territorys small size,

population and domestic market, this inelasticity has led to the highest property prices

across all sectors in the world.

This situation is particularly problematic, as Hong Kongs permanent residents

cannot merely relocate to areas that suit their budgets, they themselves comprise a

relatively static market that cannot be compared to the populations in other world cities

save for Singapore. Resultantly, Hong Kong faces an affordability crisis, and in

particular, a demographic gap that is left unaccounted for both in the private and public

markets. Nonetheless, the affordability question is not entirely understood. Home

ownership rates in territory are at 52% whilst those catered by public housing comprise

a second 30% of the market. Resultantly, further studies should focus on establishing

the needs of the remaining 18% . Are they indeed struggling young families with little

hope of attaining home ownership? Or does this remainder comprise of temporary

members whose lack of home-ownership is transitory and a natural development?

These questions deserve further analysis.

These questions, however, should delay efforts to combat the evident demand

and supply imbalance. The Hong Kong Government is in a rare situation producing

consistent budget surpluses, and thus capable of implementing substantial policy

initiatives. Ultimately, elasticity needs to be improved substantially. Tung Chee Wahs

administration saw a reversal in levels of unaffordability caused dramatic increases in

housing stock, with around 80,000 made available annually. More than ten years later,

the situation today only sees around half of such stock made available. Similarly,

Singapore, a city with broadly similar characteristics, has annual stock generation at

around 3%. Hong Kong currently operates at a measly 1%.

Resultantly, the following policy actions are strongly recommended:

The construction of 250,000 government-assisted ownership units over the next

decade, an annual addition of 0.89% to total housing stock.

Around 200,000, or around 0.7% additional stock annually, should be added to

Public Rental Housing stock over the next decade.

Supply to the private sector should be increased, leading to 300,000 to 400,000

over the next decade.

In sum, present government estimates of future stock generation should be revised

from an inadequate 1.77% annualized increase to 3% until 2024.

Works Cited

10

th

Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey: 2014.

Demographia. Oct 2013. URL: http://demographia.com/dhi.pdf

Factsheet Public Finance. Hong Kong Government. Jan 2014.

URL<http://www.gov.hk/en/about/abouthk/factsheets/docs/public_finance.pdf>

General Housing Policies on Application for Public Housing, Subsidised Home

Ownership Schemes and Estate Management. Hong Kong Government. CB(1)1604/12-

13(01). 1 April 2013.

HOMES FOR HONG KONG PEOPLE INTO THE 21

st

CENTURY. Hong

Kong Government. Feb 1998. URL: <

http://www.cityu.edu.hk/hkhousing/pdoc/ewht.pdf>

Housing Factsheet. Hong Kong Government. Jan 2014. URL:

<http://www.gov.hk/en/about/abouthk/factsheets/docs/housing.pdf>

Knight Frank Global House Price Index. Knight Frank. Q4 2013. URL:

<http://resources.knightfrank.com/GetResearchResource.ashx?versionid=2243&type=

1>

Knight Frank Global House Price Index. Knight Frank. Q4 2012. URL

<http://resources.knightfrank.com/getnewsresource.ashx?id=c802b446-9d21-49ec-

b338-0b06ec826d98&type=1>

Legislative Council Panel on Housing Home Ownership Scheme. Legislative

Council of Hong Kong. CB(1) 591/02-03(03). URL: <http://www.legco.gov.hk/yr02-

03/english/panels/hg/papers/hg0106cb1-591-3-e.pdf>

Legislative Council Panel on Housing Relaunching of Home Ownership

Scheme and Tenants Purchase Scheme. Legislative Council of Hong Kong. CB(1)

669/08-09(03). URL: <http://www.legco.gov.hk/yr08-

09/english/panels/hg/papers/hg0202cb1-669-3-e.pdf>

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BRIEF. Further Measures to Address the

Overheated Property Market. Legislative Council of Hong Kong. 26 Oct 2012. URL:

<http://www.cityu.edu.hk/hkhousing/pdoc/2012.10_Further_Measures_to_address_ove

rheated_property_markte_fahg1102-thb201210-e.pdf>

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BRIEF. New Measures to Address the Overheated

Property Market. Legislative Council of Hong Kong. 22 Feb 2013. URL:

<http://www.cityu.edu.hk/hkhousing/pdoc/2013.2_New_Measures_to_address_overhe

ated_property_market_fahg0326-fstb201302-e.pdf>

Liu, Yvonne. Growing land supply likely to cool home market in Hong Kong.

SCMP. 26 April 2014. URL: <http://www.scmp.com/property/hong-kong-

china/article/1497264/growing-land-supply-likely-cool-home-market-hong-kong>

Long Term Housing Strategy Consulatation Document. Long Term Housing

Strategy Steering Committee HKSAR Government. Sept 2013. URL:

<http://www.cityu.edu.hk/hkhousing/pdoc//2013.9.3_LTHS_consultation_doc_e.pdf>

Long Term Housing Strategy Report on Public Consultation. Long Term

Housing Strategy Steering Committee. Hong Kong Government. February 2014.

URL:<http://www.cityu.edu.hk/hkhousing/pdoc/LTHS_Report_on_Public_Consultatio

n_e_2014.2.17.pdf>

"Our Crony-capitalism Index: Planet Plutocrat." The Economist [London] 14

Mar. 2014: n. pag. Print.

Padukone, Neil. "The Unique Genius of Hong Kong's Public Transportation

System." The Atlantic [New York] 10 Sept. 2013: n. pag. Print.

Wong, Kelvin. "Day-Trippers Underpin Hong Kong Mall Rents: Real Estate."

Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 10 Sept. 2013. Web. 07 May 2014.

Savills Insights World Cities Review. Savills. H2 2013. URL:

<http://pdf.euro.savills.co.uk/residential---other/insights-world-cities-review-h2-

2013.pdf>

Ten-Year Statistical Summary. The Land Registry HKSAR Government. URL:

http://www.landreg.gov.hk/en/monthly/10years.htm

"The World's 50 Tallest Urban Agglomerations." The World's 50 Tallest Urban

Agglomerations. Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, Dec. 2009. Web. 07

May 2014.

"The World's Biggest Public Companies." Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 2014.

Web. 07 May 2014.

Stephen, Craig. Taper threatens Hong Kong property. Wall Street Journal. 26

Jan 2014.

Vallecillo, Francys. Volume of Property Deals Plunges in Hong Kong. World

Property Channel. Commercial News Asia Pacific. 30 Aug 2013. URL:

<http://www.worldpropertychannel.com/asia-pacific-commercial-news/property-

investment-falls-in-hong-kong-hong-kong-property-savills-property-deals-luxury-

residential-office-market-industrial-space-7286.php>

Vincy, Chan, and Wong, Kelvin. H.K. Builders Fall as Non-Locals Property

Tax Imposed. Bloomberg. 29 Oct 2012.

Yung, Chester. "Hong Kong Property Tycoons Face Trial." Wall Street Journal

[New York] 7 May 2014: n. pag. Print.

Appendixes

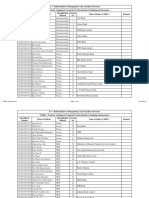

Appendix I: Overview of Sources of Government Revenue

2008-

2009

2009-

2010

2010-

2011

2011-

2012

2012-

2013

Operating

revenue

Direct

taxes

Earnings and

profits tax

Interest tax

- - - - -

Profits tax

104,1

51

76,60

5

93,18

3

118,6

00

125,6

38

Personal assessment 2,151 3,656 3,922 4,512 4,078

Property tax 833 1,678 1,647 1,949 2,259

Salaries tax

39,00

8

41,24

5

44,25

5

51,76

1

50,46

7

Indirect

taxes

Bets and sweeps tax 12,62

0

12,76

7

14,75

9

15,76

1

16,56

5

Entertainments tax - - - - -

Hotel accommodation tax (1) 223 - - - -

Stamp duties 32,16

2

42,38

3

51,00

5

44,35

6

42,88

0

Air passenger departure tax 1,626 1,617 1,813 1,947 2,029

Cross Harbour Tunnel passage tax - - - - -

Duties 6,047 6,465 7,551 7,725 8,977

General rates

7,175 9,957 8,956 9,722

11,20

4

Motor vehicle taxes 4,981 4,816 6,657 7,070 7,466

Royalties and concessions 2,389 1,596 2,452 4,849 2,736

Fees and charges (tax-loaded fees) (2) 4,870 4,895 5,113 6,769 5,127

Other

revenue

Fines, forfeitures and penalties 1,006 1,183 1,159 2,660 1,208

Properties and investments 12,48

3

12,60

1

15,80

6

16,97

1

19,26

8

Loans, reimbursements, contributions and

other receipts 3,305 3,277 2,887 3,425 3,404

Utilities 3,320 3,438 3,483 3,573 3,687

Fees and charges (excluding tax-loaded

fees) (2) 5,600 5,592 6,250 6,450 6,463

Investment

income

General revenue

account

23,35

2

17,89

3

17,82

4

20,10

5

20,02

4

Land Fund

14,18

3

11,19

6

11,07

8

11,21

6

11,12

6

Total operating revenue 281,4

85

262,8

60

299,8

00

339,4

21

344,6

06

Capital

revenue

Indirect

taxes

Estate duty

176 185 213 94 137

Taxi concessions - - - - -

Other

revenue

Land transactions - - - - -

Recovery from Housing Authority 471 864 142 163 230

Others

3,488 5,946 1,212 2,359

15,85

3

Funds Capital Works

Reserve Fund

Land premium (3)

16,93

6

39,63

2

65,54

5

84,64

4

69,56

3

Others 6,219 2,245 2,797 3,822 4,675

Capital Investment Fund 1,917 1,232 1,357 1,386 1,482

Disaster Relief Fund 5 12 4 9 1

Loan Fund 2,101 2,276 2,238 2,389 2,240

Civil Service Pension Reserve Fund 1,745 1,377 1,363 1,379 1,369

Innovation and Technology Fund 416 323 272 240 214

Lotteries Fund (3) 1,603 1,490 1,538 1,817 1,780

Total capital revenue 35,07

7

55,58

2

76,68

1

98,30

2

97,54

4

Total Government revenue 316,5

62

318,4

42

376,4

81

437,7

23

442,1

50

Appendix II: History of LTV Policy

Source: HOFINET

Appendix III: Global Office Indices Marketview

December 2013

Appendix IV:

June 2013

Source: CBRE

Appendix V: Annual International Housing Affordability Survey

Source: Demographia

Appendix VI: Global Retail Indices Marketview

Appendix VII: Hong Kong Interest Rate Policy

Index Hong

Kong

Singapore

Square Meter

Prices

$20,660 $17,709

Rental Yields 3.00 2.41%

Rents $6,198 $4,276

Price/Rent Ratio 33 yrs 41 yrs

Price/GDP per

Cap

60.07 34.92

Roundtrip Cost 2.77% 4.67%

Rental Income

Tax (Effective)

12.16% 15.13%

Capital Gains Tax

(Effective)

0.00 0.00

House Price

Change 1 year

6.3% 3.47

House Price

Change 5 years

94.89% 50.92%

House Price

Change 10 years

160.30% 77.74

Landlord and

Tenant Law

Pro

Landlord

Pro

Landlord

Economic

Freedom Rating

89.68 87.18

Economic

Freedom 5 years

10.82% -8.19%

Competitiveness

Rating

5.36 5.63

Property Rights

Index

90 90

Currency +/-

value

$0.70 $0.85

Taxes on

Residents (Av.)

n.a. n.a.

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Chapter One Extinction of ObligationsDocument46 pagesChapter One Extinction of ObligationsHemen zinahbizuNo ratings yet

- 7 Audit of Shareholders Equity and Related Accounts Dlsau Integ t31920Document5 pages7 Audit of Shareholders Equity and Related Accounts Dlsau Integ t31920Heidee ManliclicNo ratings yet

- CH 18Document15 pagesCH 18Damy RoseNo ratings yet

- Rental Agreement TemplateDocument2 pagesRental Agreement TemplateytrdfghjjhgfdxcfghNo ratings yet

- Saln-Eugene Louie G. Ibarra Fy2023Document3 pagesSaln-Eugene Louie G. Ibarra Fy2023eugene louie ibarraNo ratings yet

- Valuation of Bonds and SharesDocument39 pagesValuation of Bonds and Shareskunalacharya5No ratings yet

- Eliminating Emotions With Candlestick Signals: by Stephen W. Bigalow The Candlestick ForumDocument122 pagesEliminating Emotions With Candlestick Signals: by Stephen W. Bigalow The Candlestick Forumbruce1976@hotmail.comNo ratings yet

- Finex ServicesDocument3 pagesFinex Servicesggn08No ratings yet

- Financial Report (October 2017)Document2 pagesFinancial Report (October 2017)Marija DukićNo ratings yet

- Akuntansi 11Document3 pagesAkuntansi 11Zhida PratamaNo ratings yet

- Fraud in Banking SectorDocument30 pagesFraud in Banking SectorRavleen Kaur100% (1)

- Non Face To Face Form With AMB Declaration PDFDocument10 pagesNon Face To Face Form With AMB Declaration PDFrohit.godhani9724No ratings yet

- Cityam 2010-10-29Document52 pagesCityam 2010-10-29City A.M.No ratings yet

- Loan and Security Agreement 10Document170 pagesLoan and Security Agreement 10befaj44984No ratings yet

- Tax Invoice/Bill of Supply/Cash Memo: (Original For Recipient)Document1 pageTax Invoice/Bill of Supply/Cash Memo: (Original For Recipient)raviNo ratings yet

- Courier C129303 R6 TDK0 CADocument15 pagesCourier C129303 R6 TDK0 CARohan SmithNo ratings yet

- Research Paper - MN559990 - Batch35 - PDFDocument17 pagesResearch Paper - MN559990 - Batch35 - PDFkhushboo sharmaNo ratings yet

- Accounting For Income TaxDocument14 pagesAccounting For Income TaxJasmin Gubalane100% (1)

- Solutions For End-of-Chapter Questions and Problems: Chapter TenDocument29 pagesSolutions For End-of-Chapter Questions and Problems: Chapter Tenester jofreyNo ratings yet

- Summer Traning Report of Working Capital Manegment (CCBL)Document62 pagesSummer Traning Report of Working Capital Manegment (CCBL)PrabhatNo ratings yet

- MIS ReportDocument15 pagesMIS ReportMuhammad RizwanNo ratings yet

- Disclosure No. 132 2016 Top 100 Stockholders As of December 31 2015Document6 pagesDisclosure No. 132 2016 Top 100 Stockholders As of December 31 2015Mark AgustinNo ratings yet

- Monetary Policy and Central Banking PDFDocument2 pagesMonetary Policy and Central Banking PDFTrisia Corinne JaringNo ratings yet

- Pi IPSAS Is Cash Still King v5Document50 pagesPi IPSAS Is Cash Still King v5Grecia Dalina Vizcarra VNo ratings yet

- Fiscal Policy of EUROPEDocument11 pagesFiscal Policy of EUROPEnickedia17No ratings yet

- Iblr220800068978 PDFDocument1 pageIblr220800068978 PDFMURALI HNNo ratings yet

- IB - 19 - PetitionerDocument30 pagesIB - 19 - PetitionerKushagra TolambiaNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument3 pagesUntitledapi-234474152No ratings yet

- Transaction 0876004311Document3 pagesTransaction 0876004311โอภาส มหาศักดิ์สวัสดิ์No ratings yet

- List of Groups and Topic For Practical Assignment 1Document5 pagesList of Groups and Topic For Practical Assignment 1pareek gopalNo ratings yet