Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Coursematerials

Uploaded by

Mohamed Elmasry0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

98 views65 pagesASCP - Transfusion Practice, WAIHA

Original Title

coursematerials

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentASCP - Transfusion Practice, WAIHA

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

98 views65 pagesCoursematerials

Uploaded by

Mohamed ElmasryASCP - Transfusion Practice, WAIHA

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 65

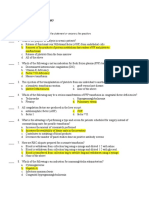

6730 Transfusion PracticesWarm Autoimmune

Hemolytic Anemia, Transfusion Triggers, and Managing

Blood Component Recalls and Withdrawals

Kimberly W. Sanford, MD, FASCP, MT(ASCP)

Phillip J. DeChristopher, MD, PhD, FASCP

Glenn E. Ramsey, MD, FASCP

2010 Annual Meeting San Francisco, CA

AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR CLINICAL PATHOLOGY

33 W. Monroe, Ste. 1600

Chicago, IL 60603

Program Content and Disclosure

The primary purpose of this activity is educational and the comments, opinions, and/or recommendations expressed by the faculty or authors

are their own and not those of the ASCP. There may be, on occasion, changes in faculty and program content.

In order to ensure balance, independence, objectivity, and scientific rigor in all its educational activities, and in accordance with ACCME

Standards, the ASCP requires all individuals in positions to influence and/or control the content of ASCP CME activities to disclose whether they

do or do not have any relevant financial relationships with proprietary entities producing health care goods or services that are discussed in the

CME activities, with the exemption of non-profit or government organizations and non-health care related companies. These relationships are

reviewed and any identified conflicts of interest are resolved prior to the activity. Faculty are asked to use generic names in any discussion of

therapeutic options, to base patient care recommendations on scientific evidence, and to base information regarding commercial

products/services on scientific methods generally accepted by the medical community. All ASCP CME activities are evaluated by participants for

the presence of any commercial bias and this input is utilized for subsequent CME planning decisions.

The individuals below have responded that they have no relevant financial relationships with commercial interests to disclose:

Course Faculty:

Kimberly W. Sanford, MD, FASCP, Phillip J . DeChristopher, MD, PhD, FASCP and Glenn E. Ramsey, MD, FASCP

Annual Meeting/ Weekend of Pathology & Educational Course Planning Committee/ Commission Members and Staff:

N. Volken Adsay, MD, FASCP Carolyn Burns, MD, FASCP Francois Cady, MD, FASCP

Michele L. Best, MT(ASCP), MASCP Nikolaj Lagwinski, MD Sondra Moran, MT(ASCP)

Cyril Fisher, MD, DSc, FRCPath, FASCP Steven H. Kroft, MD, FASCP Stacy Kiff, MT(ASCP)

Syed A. Hoda, MD, FASCP William E. Schreiber, MD, FASCP Suzanne Ziemnik, M.Ed.

Monica I. Ruiz, MD Daniel D. Mais, MD, FASCP

Kimberly W. Sanford, MD, FASCP Robert A. Goulart, MD, FASCP

Peggy Soung Sullivan, MD, FASCP Karen A. Brown, MS, MLS(ASCP)

Neil Crowson, MD, FASCP Lynnette G. Chakkaphak, MS, MT(ASCP

Syed Ali, MD, FASCP Amy J . Wendel, SCT(ASCP)

The individuals below have disclosed the following financial relationships with commercial interests:

Course Faculty:

Planning Committee/ Commission Members and Staff:

Elizabeth A. Wagar, MD, FASCP Becton Dickinson Honorarium Scientific Advisory Board

David J . Dabbs, MD, FASCP USLabs; Ventana Med Systems; Consultant service fees; Consulting

Dako

Dennis P. OMalley, MD, FASCP Clarient Salary, Stock Options Employee

David Grignon, MD, FASCP Integrated Lab. Automation Stock Shareholder

Solutions

Eric D. Hsi, MD, FASCP Allos; BD; Eli Lilly; Honorarium; Research Consultant

Facet Biotech Support

Charles Lombard, MD, FASCP Broncus Tech; Asthmatx; Stock Consultant

Neomend

Michael D. Feldman, MD, PhD, FASCP Aperio Technology, Inc., CRI Stock Options; Advisory Board; Consultant

Bioimagene Sponsored Research &

License Patents

Peter Banks, MD, FASCP Aperio Technology, Inc. Future Stock Options; Advisory Board; Consultant

Cambridge Past Stock Options

Andrew Churg, MD, FASCP Various Law Firms Regarding Consulting Fee Consultant/Expert Witness

Asbestos Disease

J oel Greenson, MD, FASCP Glaxo Smith Kline; Roche/ Consulting Fee Consultant

Genentech; Millennium Pharam;

Genetics Squared

Copyright 2010 by the American Society For Clinical Pathology

All Rights Reserved. Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form

or by any means - electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise

without the prior written permission of the publisher.

6730 Transfusion PracticesWarm Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia, Transfusion Triggers, and

Managing Blood Component Recalls and Withdrawals

Review the complex serologic findings of warm autoantibodies and recommendations for transfusion

and communication with clinicians for these patients. You will learn about current transfusion targets,

data that indicate that transfusion triggers may be dangerous, and how to manage blood component

recalls and withdrawals to ensure patient safety. You will leave with the ability to:

Recognize, evaluate and assess serologic findings of patients with autoantibodies and warm

autoimmune hemolytic anemias and discuss transfusion recommendations.

Review current transfusion targets and analyze the data of why transfusion triggers may be

dangerous.

Review management of blood component recalls and withdrawals.

Directors:

Kimberly W. Sanford, MD, FASCP, MT(ASCP)

Virginia Commonwealth University

Phillip J . DeChristopher, MD, PhD, FASCP

Loyola University Medical Center

Glenn E. Ramsey, MD, FASCP

Northwestern University Medical School

3.0 CME Credits

TM

MOC: MK PC PBL

1

Warm autoimmune hemolytic

anemia and transfusion

American Society for Clinical Pathology

S F i San Francisco

Course 6730

Kimberly W. Sanford, M.D.

Department of Pathology

Virginia Commonwealth University

Kimberly W. Sanford, M.D.

Department of Pathology gy

Virginia Commonwealth University

CME Disclosure:

No relevant financial interests

Objectives to Learn

Etiologies of autoimmune hemolytic

anemia (AIHA)

Pathogenesis of warm autoantibodies &

drug induced hemolytic anemia drug induced hemolytic anemia

Lab tests evaluating warm autoantibodies

Complications of pretransfusion testing

Communicating transfusion

recommendations

2

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia

(AIHA)

IgG and/or IgM antibodies bind to red blood cell

(RBC) antigens and initiate destruction of

autologous RBCs

Complement (C) system

Reticuloendothelial system y

Does not require exposure to allogenic blood

Alloimmune hemolytic anemia

Exposure to allogenic RBC required

Pregnancy

Transfusion

AIHA

Incidence

1:80,000 100,000 annually

Affects all ages

Peak: 4-5

th

decade

Primary AIHA

Idiopathic Idiopathic

Secondary AIHA

Lymphoproliferative disorders

Systemic Lupus Erythematous (SLE)

Females higher incidence of primary and secondary

AIHA

Classification of AIHA by frequency

Warm AIHA (WAIHA): 70%

primary (idiopathic)

secondary

Cold AIHA (CAIHA): 15%

primary (idiopathic)

secondary

Drug induced immune hemolytic anemia: 12%

Paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria : 2%

*Petz LD, Garratty G. Acquired immune hemolytic anemias. New York:

Churchill Livingstone, 1980.

3

Responsible Antibodies

41 % Warm autoantibodies (autoabs)

32% Cold autoabs

18% Drug induced abs

7% Mixed abs

2% PCH/DL abs

*Sokol RJ, Hewitt S, Stamps BK. Acta Haematol 1983;69:266-74

Warm Autoimmune Hemolytic

Anemia

Primary idiopathic

Most common

Typical testing pattern

Panreactivity

60%autoabs detected in saline 60% autoabs detected in saline

90% autoabs detected in PEG, gel or solid phase.

30% also have cold autoabs

Normal titers at 4 C

No reactivity at 30-37C

*Petz LD, Garratty G. Acquired immune hemolytic anemias. New York: Churchill

Livingstone, 1980.

Warm autoantibodies

Antibody detection methods that use PEG,

enzymes, columns, or solid-phase red

cell adherence generally enhance g y

autoantibodies.

*Leger RM. The positive direct antiglobulin test and immune-mediated

hemolysis. In: Roback J. ed: Technical Manual 16

th

edition.

4

WAIHA Pathophysiology

Microspheroctye in

C

C

C

Intravascular

hemolysis

Spleen

Remain

sequestered

Microspheroctye in

circulation

Phagocytosis by

macrophage

RBC autoab

Ab reacts with intrinsic RBC antigens

May or may not cause pathological effects in vivo

Study performed at UCLA

100 autoabs

29% hemolytic

Presence or absence of alloabs and hemolysis was

significant different

*Blackall DP, Wheeler CA. Transfusion 2007; 47:1332.

Presentation of patients with warm

autoabs

Highly variable

Asymptomatic

No decreased RBC survival No decreased RBC survival

Life threatening anemia

Fatigue, dizziness, pallor, palpitations, dyspnea

Dependent on marrow response

5

Etiologies of Autoabs

Immunoregulation breakdown

Loss of T-cell suppressor regulation

Overactive B cells

Leads to emergence of autoabs

.

Triggers for autoab formation

Infections

Increase ability of macrophages to phagocytose

coated RBC

Inflammatory process/disease a ato y p ocess/d sease

Lymphoproliferative disorder

Medications

Fludarabine

* Borthakur G, OBrien S, Wierda WG, et al. Br J Haematol

2007;136:800-5

Transfusion Stimulated Antibodies

Transfusion can stimulate allo-abs and autoabs

RBC autoimmunization recognized 60 years ago

*Dameshek W, Levine P. NEJM 1943;228:641-4.

Average incidence of alloimmunization after

t f i i 2 10% transfusion is 2-10%

*Hewitt, PE, et al. Br J Haematol 1988. 69:541-4.

*Schonewille H, et al. Transfusion 2006. 250-6.

Chronically transfused patients alloimmunization

rate 18-60%

*Rosse WF, et al.Blood 1990. 76:1431-7.

*Vichinsky EP, et al. NEJM 1990. 322:1617-21

6

Transfusion stimulated Autoabs

8535 patients transfused, 34 cases of +DATs

25% of eluates were panreactive

Autoab formation

Persisted beyond life span of transfused RBC

abs adsorb onto recipients antigen-negative RBC

Conclusions:

Alloimmunization stimulant for autoab formation

Autoab production after transfusion is higher than

reported.

*Ness PM, et al. Transfusion 1990. 30:688-93

2004 study by Young et al.

2618 patients transfused

121 patients developed autoabs

Positive direct antiglobulin test (DAT) and indirect antiglobulin

test (IAT)

41 patients developed alloabs and autoabs

12 developed autoabs temporally associated

with alloimmunization

80 ti t d l d t b 80 patient developed autoabs

Conclusions

Autoimmunization complication of transfusion

Conservative transfusion practices

*Young PP, et al Transfusion 2004. 44:67-72.

Antibodies coating RBC

Quantity and type of immunoglobulin coating RBC

influences hemolysis

IgG1 and IgG3 versus IgG2 and IgG4

Macrophage receptors for IgG1 and IgG3

IgG1 major subclass in AIHA

Complement on RBC accelerates removal

Spleen and liver remove coated RBC

*Gehrs BC, Friedberg RC. American Journal of Hematology 2002

7

Lab detection of autoabs

Ab screens and panels are panreactive.

Negative if high binding constant or low titer.

Autocontrol is positive

Patient RBC & patient plasma

DAT results for warm autoab

IgG positive +/- C3b

The predictive value of positive DAT

83% in a patient with hemolytic anemia

1.4% in patient without hemolytic anemia

*Kaplan HS, et al. Diagnostic Med 1985;8:29-32

DAT: sensitized RBCs + AHG

AHG reagent

Patient RBC

Patient RBC

Patient RBC

Antibody coating RBC

in vivo

DATs

Healthy adults

50-90 IgG molecules/RBC

5-40 C3d molecules/RBC

*Garratty G. Transfus Med Rev 1987;47-57.

*Freedman J. Transfus Med Rev 1987; 58-70

DAT detection

100-500 molecules of IgG per RBC

400-1100 molecules of C3d per RBC

1-15% of hospital patients have positive DATs

*Petz LD, Garratty G. Immune hemolytic anemias. 2004

8

Causes of positive DATs

Positive DATs with/without shortened RBC survivial

Autoabs to intrinsic RBC antigens

Alloabs bound to transfused donor RBC

Passively acquired alloabs

Maternal alloabs on fetal RBC

Abs against drugs bound to RBC membrane.

IgG or complement coating of cells due to

medications.

Adsorbed proteins/immunoglobulins on RBC

Hypergammaglobulinemias

IVIg

Investigating +DAT AABB Technical

Manual 15

th

ed

Elutions

Perform on all samples with IgG positive DAT

No need to perform eluate on C3 positive only

DAT DAT

Eluates can concentrate small amounts of IgG

antibody undetectable in plasma.

9

Elutions

Ab dissociates

from RBC

Elution

methods:

1. Heat

2. Lui Freeze-thaw

3. Acid elution

4. Digitonin acid

Test eluate with panel of cells

Alloantibody specificity

Delayed serologic transfusion reactions (DSTR)

Acute or delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions

(DHTR)

Hemolytic disease of the fetus or newborn (HDFN)

Panreactive eluates

Autoantibody

Eluate in WAIHA

Warm autoabs confirmed by elution

upon initial diagnosis

during pretransfusion testing during pretransfusion testing

Eluate reacts with virtually every cell tested.

10

Autoab specificity

Typically panreactive

Specificity for simple Rh antigens

D C E c e D, C, E, c, e

More commonly detected in LISS

Other specificities include

LW, Kell, Kidd, Duffy and Diego

Non reactive eluates

Eluate is Anti- A or B abs

Test A

1

and B cells with eluate.

Ab to low incidence antigen

79 % of hospital patients with + DATs have 79 % of hospital patients with DATs have

nonreactive eluates

One explanation for this is the non-specific uptake

of proteins on RBC especially in patients with

increased gamma globulin levels.

Medication

*Toy PT, Chin CA, Reid ME, Burns MA. Vox San 1985; 49:215-20.

3 Mechanisms of drug induced HA

Drug adsorption

Drug dependent Drug dependent

Autoimmune

induction

AABB Technical Manual 15th edition

11

Drug Adsorption Mechanism

Medication/metabolites bind to RBC

Penicillin covalently binds to RBC proteins

Anti-medication IgG ab sensitizes cell for

immune clearance immune clearance

DAT usually positive for IgG, eluate negative

Rarely causes hemolysis

7 days before hemolysis starts

Extravascular hemolysis

Drug adsorption Mechanism

AABB Technical Manual 15

th

edition

Drug-dependent Ab Mechanism

Medication/metabolite

binds transiently to

proteins on RBC

surface

Creates immunogen

Ab production Ab production

Binds to

drug/metabolites on

RBC

IgG /IgM can activating

C

Small amount of drug

required in sensitized

patients

AABB Technical Manual 15th edition

12

Drug dependent mechanism

Hemolysis abrupt, severe

Hours or days

Intravascular hemolysis

Massive hemoglobinemia/hemoglobinuria

Renal failure, DIC, shock

Medications

2

nd

and 3

rd

generation cephalosporins

NSAIDs

Autoimmune induction mechanism

Medication induces RBC

autoab

Medications

- Methyldopa, levodopa,

procainamide

11-36% of patients form

+DAT after 3 6 months +DAT after 3-6 months

<1% have clinical

hemolysis

Hemolytic anemia

Mild-moderate

extravascular hemolysis

Gradual anemia

Hemolysis may persist

weeks-months after drug

stopped

AABB Technical Manual 15th edition

Treatment for Drug induced HA

Withdraw the drug

Some instances hemolysis may persist but short

lived lived

Rarely requires treatment

13

Summary of Drug Induced HA

Type DAT +

due to

Serum Antibody Hematologic

Manifestations

Drug adsorption IgG, C3d Ab reacts with drug

coating RBC

Moderate

hemolysis,

extravascular

Drug-dependent C3d Ab to drug & RBC

membrane

Abrupt, severe

intravascular

hemolysis

Autoimmune

induction

IgG Autoab to RBC

membrane

Mild-moderate,

extravascular

hemolysis

Adsorption techniques

Detect underlying alloabs

Pretreatment of autologous cells to remove bound

autoab for adsorption of autoabs

Treatment:

Heat cells at 56C for 3-5 minutes and treatment with proteolytic

enzymes

ZZAP: mix of papain/ficin and DTT

PEG treatment

Treated cells incubated with plasma

Autoadsorptions

Multiple sequential autoadsorptions may be

necessary

Adsorbed plasma should have no reactivity with Adsorbed plasma should have no reactivity with

autologous RBC.

Perform full panels using absorbed plasma

14

Alloadsorptions

Patients transfused within 3 months

Reticulocyte harvest

Allogenic adsorptions

Use donor cells of different phenotypes to adsorb

autoabs autoabs

Only look to rule out clinically significant abs

Rh antigens, K, Fys, Jks, Ss.

R

1

R

1

, R

2

R

2

, rr

Abs to high frequency antigens cannot be excluded

since donor cells express antigen

Alloadsorption

Alloadsorption performed several times until nonreactive

>3 adsorptions can dilute specimen

React adsorbed plasma with panel cells p p

Phenotypes of adsorbing cells are known

If adsorb with Jk(a-) cell

Adsorbed plasma reacts with Jk(a+) panel cell

Interpret as underlying anti-Jk

a

Transfusion

Autoantibodies mask underlying

alloantibodies that increases the risk

of a hemolytic transfusion reaction of a hemolytic transfusion reaction,

therefore conservative transfusion

should be practiced

15

Selecting blood products

Adsorption techniques ruling out alloab before

transfusion

Underlying alloab, select ag negative blood

Autoab with ag specificity Autoab with ag specificity

Ag negative if active hemolysis

If no hemolysis, ag negative blood debatable

Even ag negative blood hemolyzed

Consider zygosity

Phenotypically matched RBC

Patient not chronically transfused

Not required

Chronically transfused patients

Patients with sickle cell anemia

C, E, K matched in sickle cell patients

Frequency of C, E, K, Fya, Fyb, Jkb and S ags different than

donors

Anti-C,E, K account for 60-98 % of allo-abs

Decreased alloimmunization rate from 3 to 0.5% per unit

*Vichinsky, EP et al. Transfusion 2001.1086-92

Crossmatching and Transfusion

Selecting blood products

Antigen neg for underlying alloabs

Perform autocontrol with full crossmatches

Least incompatible with autocontrol p

Transfusion should be reserved for life-threatening

anemia

Need to increase oxygen carrying capacity

Patients at risk

Cardiovascular disease

Cerebrovascular ischemia

16

Communication with clinicians

Direct contact with clinician

Gather patients history to assess risk of alloimmunization

Transfusion & pregnancy history

Determine need for transfusion Determine need for transfusion

Symtomatic anemia, bleeding, cardiovascular disease, other

comorbidities

Discuss investigation for underlying alloabs

Alloabs present or absent

Assure blood is ABO compatible

Risk of alloimmunization

Discuss laboratory investigation

Search for compatible blood is futile

Possibly phenotype patient

Clinician and blood bank physician together should

approve transfusion

Risk vs. benefit clinical decision

Conservative transfusion practice

Do not deprive patient of transfusions when anemia is severe

Transfuse slowly

If hemoglobin decreases consider underlying alloab

*Ness PM, Transfusion 2006. 46:1859-62.

Transfusing patients with WAIHA

Monitor closely & transfuse when medical team present

Patients with little in vivo destruction tolerate

transfusions

Survival of transfused RBC is similar to patient RBC

Suppress erythropoiesis Suppress erythropoiesis

Possibly intensifies autoantibody titer

Debatable

Increased risk of hemolysis

Hemolyze auto and transfused RBC

Increases complexity of serologic testing

Weigh risks vs. benefits of transfusion

17

Frequency of testing patient

AABB Standards require new sample every 3 days.

Some argue this is too frequent, unnecessary and

too costly for minimal reward.

Average incidence of alloimmunization after

transfusion is 2-10%

*Hewitt, PE, et al. Br J Haematol 1988. 69:541-4.

*Schonewille H, et al. Transfusion 2006. 250-6.

Alloimmunization rate in patients

with warm autoabs

Leger and Garratty demonstrated 40%

alloimmunization rate with alloantibodies after

transfusion

*Leger RM, Garraty G. Transfusion 1999:39:11-6

Branch and Petz reviewed 7 independent studies Branch and Petz reviewed 7 independent studies

demonstrated 12-40 % alloimmunization rate

*Branch DR, Petz LD. Transfusion 1999:39:6-10

Incidence of autoabs detected in coexistence with

newly detected alloab is up to 50%

*Wheeler CA, et al. Am J Clin Pathol 2004. 680-5

Summary of studies

Exclusion of underlying alloantibodies important

in this high risk group

I d ti it t l ith Increased reactivity not always seen with some

underlying alloantibodies.

18

Medical therapies

Glucocorticoids

Prednisone 60 mg/day for 10-14 days, then taper

70% demonstrate improvement

10% non-responders, can attempt 80-100 mg/day

Inhibits monocyte-RBC interaction in spleen

Rituximab

Monoclonal CD20 ab used to treat immune cytopenias

375mg/m

2

weekly for 4-6 weeks

Smaller maintenance dose in responders

Other therapies

Immunosuppressants

Cyclospoirine, mycophenolate, antithymocyte globulin

IVIG

Less effective with WAIHA vs. ITP

Blocks Fc receptors on macrophages in RES

Cytotoxic drugs Cytotoxic drugs

Use for patients not responding to steroids

Splenectomy is contraindicated

Azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil

Splenectomy

Delay until medical therapy fails

2/3 of patients demonstrate partial or complete response

Iron and Folate supplements

Conclusions

Patients with + autocontrols should have DATs

performed.

Positive broad spectrum DATs need monospecific IgG

and complement DAT performed.

Eluates

Adsorption techniques

Crossmatches

Communication with clinicians

Transfuse conservatively

Medical or surgical therapies

Treat underlying disease

19

References

Petz LD, Garratty G. Acquired immune hemolytic anemias. New York: Churchill

Livingstone, 1980

Sokol RJ, Hewitt S, Stamps BK. Autoimmune haemolysis: Mixed warm and cold

antibody type. Acta Haematol 1983;69:266-74

Blackall DP, Wheeler CA. Contemporaneous autoantibodies and alloantibodies.

Transfusion 2007;47:1332.

Borthakur G, OBrien S, Wierda WG, et al. Immune anaemias in patients with chronic

lymphocytic leukaemia treated with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab-

incidence and predictors. Br J Haematol 2007;136:800-5.

Dameshek W. Levine P. Isoimmunization with rh factor in acquired hemolytic anemia.

N Engl J Med 1943;228:641-4. g ;

Hewitt PE, Macintyre EA, Devenish A, et al. A prospective study of the incidence of

delayed haemolytic transfusion reactions following peri-operative blood transfusion.

Br J Haematol 1988;69:541-4.

Rossee WF, Gallagher D, Kinney TR, et al. Transfusion and alloimmuniztion in sickle

cell disease. The cooperative study of sickle cell disease. Blood 1990. 76:1431-7.

Vichinsky EP, Earles A, Johnson RA, Hoag MS, Williams A, Lubin B.

Alloimmunization in sickle cell anemia and transfusion of racially unmatched blood.

NEJM 1990. 332:1617-21.

Gehrs BC, Friedberg RC. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia. American Journal of

Hematology 2002; 69: 258-71.

Ness ONm Shirey RS, Thoman SK, et al. The differentiation of delayed serologic and

delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions: incidence, long-term serologic findings and

clinical significance. Transfusion 1990.30:668-93

References

Schonewille H, van de Watering LMG, Loomans DSE, et al. Red blood cell

alloantibodies after transfusion: factors influencing incidence and specificity.

Transfusion 2006; 46:250-6.

Kaplan HS, Garratty G. Predictive value of direct antiglobulin test results. Diagnostic

Med 1985;8:29-32.

Garratty G. The significance of IgG on the red cell surface. Transfus Med Rev

1987;1:47-57.

Freedman J. The significance of complement on the red cell surface. Transfus Med

Rev 1987;1:58-70.

Toy PT, Chin CA, Reid ME, Burns MA. Factors associated with positive direct

antiglobulin tests in pretransfusion patients: a case control study. Vox Sang 1985;

49:215-20

Vichinsky EP, Luban NLC, Wright E, et al. Prospective RBC phenotype matching in a

stroke-prevention trial in sickle cell anemia: a multicenter transfusion trial. Transfusion

2001;41:1086-92.

Leger RM, Garratty G. Evaluation of methods for detecting alloantibodies.

Transfusion 1999;39:11-16.

Wheeler CA, Calhoun L, Blackall DP. Warm reactive autoantibodies : clinical and

serologic correlations. Am J Clin Pathol 2004;122:680-5.

Ness PM. How do I encourage clinicians to transfuse mismatched blood to patients

with autoimmune hemolytic anemia in urgent situations. Transfusion 2006. 46:1859-

62.

Leger RM. The positive direct antiglobulin test and immune mediated hemolysis. In:

Roback J. Combs MR, Grossman B, et al. eds. Technical Manual. 16

th

edition.

Bethesda, MD: AABB Press 2008:489-521.

Duffy TP. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia and paryoxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

In: Simon TL, Snyder EL, Stowell CP, et al. eds. Rossis Principles of Transfusion

Medicine. 4

th

edition. Bethesda, MD: AABB Press 2009:321-43.

9/21/2010

1

Transfusion Practices:

Managing Blood Component

Recalls and Withdrawals

American Society for Clinical Pathology

San Francisco 2010

Course 6730

1

Course 6730

Glenn Ramsey, MD

Department of Pathology

Northwestern University

Chicago, Illinois

Transfusion Practices:

Managing Blood Component

Recalls and Withdrawals

American Society for Clinical Pathology

San Francisco 2010

Course 6730

2

Course 6730

Glenn Ramsey, MD

CME Disclosure:

No relevant financial interests

Transfusion Practices:

Managing Blood Component g g p

Recalls and Withdrawals

Glenn Ramsey, MD

Department of Pathology

Northwestern University, Chicago, IL

LochDunvegan, Isle of Skye, Scotland

9/21/2010

2

Outline

Recalls and market withdrawals

Biological product deviation reports

Estimated 1 in 320 blood components

General management

4

Compliance, SOP, training, rapid action

Physician notification

Tangible risk of infection or adverse effect

Selected problems

High-risk transfusion?

More emerging infections

Types Of Notices About

Issued Blood Components

Lookback--donor now has infection (HIV, HCV, etc)

Recallproduct in violation of law, subject to legal action

5

Market Withdrawalless significant violation

Quarantineisolate unit, pending above determination

But most units have been transfused before notices

Platelets 5 days, RBCs 42 days storage

HIV & HCV Lookbacks

21 CFR 610.47, revised 2008

New lookbacks for HIV+& HCV+donors found now:

Donor services--

Quarantine in-dated products within 3 days

If donor confirmed+, trace past units as far back

as records permit (unless >12 months before a

ti t t)

6

negative test)

Transfusion services--

Trace recipients within 12 weeks of receiving

notice: Reasonable attempts

Incompetent or minor patient: find legal rep or

relative

Deceased recipient: HCV notice not required

HIVnext of kin notified

9/21/2010

3

Lookback Reports from Blood Establishments to FDA

Lookback Rule Revised, 2008

300

400

500

600

HCV

HIV

7

0

100

200

300

FY05 FY06 FY07 FY08 FY09

FDA Bi ol ogi cal Product Devi ati on Report, FY09

HIV

HBV

Recalls

21 CFR 7.3, 7.40 et seq.

Remove or correct products in violation of FDA law and

subject to legal action

Consignees should carry out instructions immediately

Class I: reasonable probability of serious adverse

8

Class I: reasonable probability of serious adverse

consequences or death

Class II: temporary or reversible adverse consequences

or remote probability of serious adverse conseq.

Class III: not likely to cause adverse consequences

Published in FDA Enforcement Report weekly

Ramsey G, Sherman LA. Transfusion 39:473,1999;40:253,2000

Bozzo T. Transfusion 39:439, 1999

Market Withdrawals

Products with minor violations, not subject to legal action

May be beyond control of manufacturer

E.g., post-donation information about donor

Not published by FDA, numbers of withdrawals or units

i l d k

9

involved are unknown

Biological product deviations often lead to withdrawals

9/21/2010

4

2006 Recalls

FDA Enforcement Reports (weekly), 2006

Ramsey G, Transfusion 47(suppl):34A, 2007

1,130 blood component recalls of 13,758 units

10

About 1 in 2,000 available blood components recalled

Common Recal l Reasons Wi thin Categori es, 2006

Other, 780

629

362 Temp

321 License

Other, 1332

2500

3000

3500

4000

4500

5000

i

t

s

11

411 Malaria

1062

Donor

Suitability

1686

Store Temp

1421

Arm Prep

1264

GMP 121 vCJD

313 Ship Temp

1342

Sterility 926

QC

Clots

Other, 331

Other, 104

Other, 61

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

Preparation Collection Store/Ship Inadeq Donor Hx RiskFactors

U

n

Biological Product Deviation Reporting

21 CFR 606.171, instituted 2001

Key elements of BPD scope:

Manufacturing

E.g., patient specimen, but not patient care

12

g , p p , p

Deviations affecting safety, purity, potency

No longer errors and accidents

Only if product was distributed

If not distributed, not reportable

Investigation still required (cGMP)

9/21/2010

5

Biological Product Deviation Reports

Licensed Facilities, FY 09 = 25,481

Donor-Related

Screening 1914

Collection 929

General

QC, Distribution 1662

Component Prep 420

FDAAnnual Summary, BPD

Reports, www.fda.gov

Collection 929

Viral Testing 39

Deferral 37

Post-Donation

Information 18,558

Component Prep 420

Routine Testing 289

Labeling 749

Miscellaneous 884

Biological Product Deviations:

Post-Donation Information

Travel

Malaria

vCJ D

Post-donation illness

History tattoo <12 mo

History tissue or organ tpt

Hx prior disease/surgery

Hx hepatitis or exposure

Sex partner: HIV grp O risk

Other exposures

14

Male-male sex

Medications

Antiandrogens

Retinoids

IV drug use

Pre- or post-donation

positive viral marker

Cancer before or after

donationno longer BPD

Biological Product Deviations:

Post-Donation Information

Highlighted by NIH/NHLBI for study by REDS-II*

Travel---malaria (tropics), variant CJ D (Europe)

Medicaldeferring illnesses or medications

High risk behaviors/exposure

Sexual (High-risk partner male sex with male)

*Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor

Study II

Sexual (High-risk partner, male sex with male)

Nonsexual (IVDU, jail)

Blood/disease exposurestattoo, piercing, needlestick

Transfusion 49 Suppl 3S:52A (x2), 2009--AABB meeting

Fed Reg 75:8080, 2/23/2010, planned donor survey

9/21/2010

6

Post-Donation Information: Donor Analysis

Licensed facilities, FDA BPD Annual Report, FY09:

93% of PDI donors knew information before donation

Only 7% discovered their PDI after donation

PDI discovery: later donation 93%; donor call 5%

16

Donor survey, Transfusion 49 Suppl 3S:52A, 2009

48% made two ineligible donations

Trends: male, older, better educated (travel)

Common Blood Components Recalls, vs.

Biological Product Deviations (Licensed)--Post Donation Information

1261 Other PDI

1159 Cancer 817 Tattoo

618 Male sex

603 Finasteride

421 IVDU

5398

Other

15,000

20,000

25,000

BPDs for PDI

(Includes 44 Potential Recalls)

PDI: 80% of all BPDs

Half involve >1 donation

3 components per BPD?

17

6562

Malaria

5659

vCJD

0

5,000

10,000

Preparation Collection Store/Ship Inadeq Donor

Hx

Risk Factors PDI BPDs

Units in Recalls:

Blood Component Notices in US:

Estimated Frequency

Recalls: 13,758 units in FDA FY06 Enforcement Reports

Market withdrawals:

Est. from Biological Product Deviations (FDA FY08)

Post-donation information, ?3 components/report:

18 500 BPDs x 3 =55 500 units

18

18,500 BPDs x 3 =55,500 units

Other BPDs, ?2 components/report:

7,000 BPDs x 2 =14,000 units

Estimated 83,000 units recalled or withdrawn

26,568,000 units available in US (AABB/HHS 2006)

0.31%, or 1 in 320 blood components in US

Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago: 0.45%

9/21/2010

7

Outline

Recalls and market withdrawals

Biological product deviation reports

Estimated 1 in 320 blood components

General management

19

Compliance, SOP, training, rapid action

Physician notification

Tangible risk of infection or adverse effect

Selected problems

High-risk transfusion?

More emerging infections

CAP Lab Accreditation Checklist, 2010

Transfusion Medicine

TRM.42120, Phase II:

Identify/quarantine units from donors now reactive

in screening test

TRM.42135, Phase I:

20

Have SOP for managing quarantines, recalls,

withdrawals

TRM.42170, Phase II:

Follow FDA and CMS regulations/guidelines for

recipients given potentially infectious transfusion

HIV/HCV lookbacks & other guidelines

AABB Standards, 25th ed., 2008

7.0. Deviations, Nonconformances, and Complications

7.1 Nonconformances

7.1.4 Released Nonconforming Blood, Components

Evaluated to determine effect on quality

When quality may have been affected, report to

customer(other department or facility)

21

customer (other department or facility)

Maintain records of nature and action

Keep five years

7.4.6. Look-Back. Per FDA rules and recommendations

[FDA: Keep lookback records 10 years from notice]

9/21/2010

8

General Considerations I

Have a procedure for managing notifications

Training

Promptly follow instructions from blood supplier

24/7 access to fax or secure e-mail for large

22

notices

Quarantine units physically and electronically

Medical evaluation as needed

Get more info from blood supplier if needed

Donor (was/will be) tested later?

Ramsey, Transfusion Med Rev 18:36, 2004

General Considerations II

Document actions

If phone, then paper; track resolution

Database by unit? By recipient?

Keep records as required (5 yrs or lookbacks 10 yrs)

23

Keep records as required (5 yrs, or lookbacks 10 yrs)

Was Source Plasma or Recovered Plasma made and

sent elsewhere?

Oversight Options

Transfusion committee

Approve policies

Review significant notices

Improve awareness of potential for post-transfusion

bl

24

problems

Risk management/legal

Serious problems or large recalls

Patient/public relations assistance

9/21/2010

9

25 LochSnizort, Isle of Skye, Scotland

Outline

Recalls and market withdrawals

Biological product deviation reports

Estimated 1 in 320 blood components

General management

26

Compliance, SOP, training, rapid action

Physician notification

Tangible risk of infection or adverse effect

Selected problems

High-risk transfusion?

More emerging infections

Inform Transfusing Physician?

Our general approaches:

As required or recommended by FDA-yes

HIV, HCV lookback

If tangible potential for disease transmissionyes

27

If potential for transfusion reaction (sterility, storage):

check for reaction report

9/21/2010

10

Notify Physician? Yes or Suggested Yes:

FDA rule:

HIV lookback (patient or next of kin)

HCV lookback (patient alive)

Other donor/unit infection, confirmed:

HBV sAg or NAT*, Chagas, West Nile NAT

Bacteria in component or co-component

28

Bacteria in component or co component

Tangible potential infection risk:

HIV or hepatitis risk factor*

Malaria travelhigh-risk region and cellular unit

Improper donor screening or testing*

*Unless later donor testing rules out window period

Viral Marker Windows

Seroconversion periods important

Timing of donor exposure before donation

29

Timing of donor exposure before donation

Timing of subsequent testing (interim donations)

May rule out recipient exposure in some cases

When to test patients after transfusion

Window Periods (days)

Anti-HIV mean 22 range 6-38

HIV MP-NAT 9 7-12

Anti-HCV 70 54-192

HCV MP NAT 7 NA

30

HCV MP-NAT 7 NA

HBsAg 38-43 (06) 37-87 (05)

HBV MP-NAT 32-38 (06) NA

MP-NAT=Mini-pool nucleic acid test NA=not available

Busch, Transfusion 45:254, 2005

Kleinman, J Clin Virol 36(S1):S23, 2006

9/21/2010

11

Notify Physician? It Depends-I

If transfusion reaction occurred:

Donor or unit bacterial infection risk

Antibiotics, arm preparation, other sterility concern

Component content problem

Clots, hemolysis

St bl

31

Storage problem

Temperature, incorrectly extended expiration

Incorrect CMV status or leukoreduction

If recipient was at risk for CMV

Teratogenic medication (antiandrogen, retinoid)

If recipient was pregnant

Notify Physician? It Depends-II

Labeling problem:

Compatibility: blood type, crossmatch, antigen typing

If reaction or potential for delayed reaction

32

Collection bag or apheresis device problem

Evaluate details

Notify Physician? Suggested No:

Post-donation information:

vCJ D residence risk

Malaria travelMexico, Central America

Donor history of:

33

Cancer, post-donation illness

Viral screen, unconfirmed:

HBcAb; EIA+other markers not confirmed

Donor record/ID/unit number

No, but fix recipients unit-number record if needed

Unit quality control or volume

9/21/2010

12

Recalled Units: Physician Notification?

(Withdrawals Not Included)

Arm Prep or

Sterility

Storage Temp

RBCAg

Leukored?

Other

Other

Malaria, 411

44%: Txn Rxn?

5% More

Info

34

Other YES, 181

QC

Donor History

Adeq?

Other GMP

Testing, 204

46% No

6% Yes

Canadian Policy Recommendations

Heddle NM et al, Transfusion 48:2585, 2008

McMaster University survey; recommendations

Recipient notification issues include:

Develop national or provincial guidelines

35

Notices to hospitals should include recommendations

Hospital SOPs should address decision-making

Health care personnel should be given adequate

information for recipient notification if needed

Educate hospital CEOs and risk management personnel

Outline

Recalls and market withdrawals

Biological product deviation reports

Estimated 1 in 320 blood components

General management

36

Compliance, SOP, training, rapid action

Physician notification

Tangible risk of infection or adverse effect

Selected problems

High-risk transfusion?

More emerging infections

9/21/2010

13

High Concern for Viral Exposure?

Donor with recent confirmed viral exposure or new

confirmed infection? HBV, HCV, HIV?

Consult infectious disease service for advice about

recipient: immediate counseling and treatment?

37

Post-exposure prophylaxis information:

National PEPLine (24 hr)

1-888-HIV-4911 (448-4911)

General HIV therapy consultation:

National HIV Warmline (8am-8pm ET M-F)

1-800-933-3413

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

CDC post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) guidelines

see MMWR Recommendations & Reports

50(RR-11), 2001: Occupational HBV/HCV/HIV

54(RR-02), 2005: Non-occupational HIV

54(RR-09) 2005: Occupational HIV

38

54(RR-09), 2005: Occupational HIV

57(RR-6), 2008: Mass-casualty HBV/HCV/HIV exposure

NY State Dept Health: www.ceitraining.org

Current NY guidelines

Adult or pediatric, occupational or not

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Timing

HIV and HBVrapid therapy if possible

HIV: antiretroviral medications

CDC: ASAP, within hours rather than days (05)

NY--ideally <2 hr, and generally not after 36 hr

But max time cannot be stated with certainty

39

y

HBV: If exposee not immune:

HBV Immune Globulin and vaccine

Ideally <24 hr, but not after 14 days

HCV: No effective PEP, not recommended

9/21/2010

14

Chagas+ Donor Lookback

AABB Bulletin #06-08, 12/13/06, recommendations:

Withdraw prior in-dated products when donor screen+

Lookback on all confirmed-positive donors prior units

Confirmed=positive on second test (RIPA, IFA, other)

40

Include all frozen units?infectious, but data limited

As far back as records go

Lookback recipient testing: Few if any infected recipients

without their own exposure risk have been found

Donors in US not as infectious as Latin Amer donors

More Emerging Agents

AABB Task Force, Emerging Infectious Disease Agents

Stramer SL, Transfusion 49(suppl), Aug 2009

Highest priority (in addition to vCJ D):

Babesia

41

Dengue

2010: Chronic fatigue syndrome and XMRV

Xenotropic murine-leukemia-virus-associated retrovirus

Other MLV-related viruses?

Babesia

Intraerythrocytic parasite, regionally endemic

Dozens of transfusion cases, several fatalities

Current donor deferral for history of illness (AABB)

Donor testing under consideration

42

Issues for evaluating past transfusions from +donors:

Transmissions have been from RBCs only

Illness incubation 1-9 weeks

Recipient susceptibility factors (in tick inoculations):

Infants, elderly, immunosuppressed, asplenic

9/21/2010

15

Dengue

Flavivirus, arthropod-borne like WNV, tropical climes

Endemic in Caribbean and US-Mexico border areas

40-80% antibody rates

Puerto Rico donor pilot testing, Amer Red Cross

1 in 1400 donations viremic

43

1 in 1400 donations viremic

Two transfusion infections seen in SE Asia

Donor testing if done would be NAT

Issues for evaluating past transfusions from +donors:

Incubation period until illness 3-14 days

Short-term viremia before-during infection/illness

Perhaps 120d donor deferral after +NAT, like WNV?

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) and XMRV

Gammaretroviruses: feline, murine leukemia (MLV) viruses

Xenotropic Murine-leukemia-virus-associated RetroVirus

CFS: >6 months of fatigue, weakness, myalgia, impaired

memory or concentration, insomnia (CDC.gov)

Some studies link XMRV to CFS and prostate cancer

FDA/NIH PNAS 8/23/10 MLV l t d i RNA i

44

FDA/NIH, PNAS 8/23/10: MLV-related virus gag RNA in

CFS patients 87%, blood donors 7%

No evidence for transfusion transmission to date, but

AABB, Canada, Australia/NZ blood services, 2010:

Donor deferral for history of CFS diagnosis

No guidance included on past donations of new deferrals

Implication for past transfused units unknown at this time

DuntulmCastle ruins (Clan MacDonald), Isle of Skye

Harris (tweed) on horizon

9/21/2010

16

Outline Summary

Recalls and market withdrawals

Biological product deviation reports

Estimated 1 in 320 blood components

General management

46

Compliance, SOP, training, rapid action

Physician notification

Tangible risk of infection or adverse effect

Selected problems

High-risk transfusion

More emerging infections

9/21/2010

1

Transfusion Transfusion Triggers Triggers

2010 ASCP Annual Meeting

Friday, October 29, 2010

Phillip J. DeChristopher, MD, PhD

Medical Director, Transfusion Medicine / Blood Bank / Apheresis

Professor of Pathology

Loyola University Medical Center

Maywood, Illinois

(T) 708-327-2609

E-mail: pdechristopher@lumc.edu

Lecture Objectives

Overview of Some Complications of

Transfusion

Blood Component Types to Consider

Indications for Blood Use

Non-indications for Blood Use

Situations where Blood Use is Beneficial

Simplified Principles of Blood Management

Before You Pull that Trigger, Heres a

Number of Things to Consider

9/21/2010

2

Adverse Effects of Allogeneic Transfusion

1

Infectious Complications

Viral, bacterial contamination of platelets*

(1:3000), others (vCJ D, WNV, Chagas Disease,

babesiosis, Dengue fever)

Febrile and allergic reactions

Hemolytic transfusion reactions* (clerical error)

Mistransfusion incidence 1:16,000

Other

Microchimerism (50% of trauma pts @ discharge/

30% @ 1 year)

2

, graft vs. host disease

SIRS, TACO (1:350)

3

, TRALI

4

*

* Leading causes of morbidity and mortality

1. Goodnough, Crit Care Med 2003;31(12S)

2. Utter, Transfusion 2006;46

3. Rana, Transfusion 2006;46

4. Toy, Crit Care Med 2005;33(4)

Transfusion therapy is a set of processes,

not just a product

Recruitdonor

Screendonor

Collectunit

Preparecomponents

Infectious diseases

Pre-TXtesting

Medical reasonto TX

Issueunit

Administer atbedside

Monitor &evaluate

Product: Blood safety

Entire process: Blood transfusion safety

testing

AfterS. Dzik, MD BloodTransfusionService, MGH, Boston

Practice Guidelines are a Kind

of Practice Parameter

Standards

Accepted principlesof patient management

Practice variation NOT expected p

Guidelines

Recommendations / strategies for patient management

Practice variation is reasonable

Practice Options

Practice variation expected

Incorporate substantial patient- and physician-specific

information

9/21/2010

3

Defining Practice Guidelines

Consensus statements that are

systematically developed to assist

practitioner and patient decisions about

appropriate health care for specific clinical appropriate health care for specific clinical

circumstances

Field MJ. Clinical practice guidelines: Directions for a new agency. Institute of

Medicine, Washington, DC, National Academy Press. 1990.

Grading the Level of Evidence

Grade I

Randomized, controlled trials

Grade II-1

Non-randomized, controlled trials Non randomized, controlled trials

Grade II-2 Controlled observational studies

(e.g., cohort studies)

Grade II-3

Uncontrolled observational studies

Grade III Descriptive studies; expert opinion

WW II Medic Administers IV Plasma to Wounded GI:

The Value of Blood Transfusion was Recognized

Before Randomized Controlled Trials

9/21/2010

4

Red Blood Cell Unit

The 1988 NIH Consensus Conference on

Perioperative RBC Transfusion

Transfuse red blood cells to increase

oxygen-carrying capacity in anemic

patients

?Death knell to the 10/30 Rule

NIH Consensus Development Panel. Perioperative red cell transfusions. JAMA 1988;260:2700-03.

Differing Views on the RBC

Transfusion Target

The Internists View

Anemia cannot be defined numerically

RBC's are transfused to symptomatic, anemic patients

A i d h l i l dt bidit & Anemia and hypovolemia lead to severe morbidity &

mortality

Promulgated a [Hgb] trigger of 7 g / dL as

reasonable

Blood transfusion is an outcome to be avoided

American College of Physicians. Practice strategies for elective red blood cell transfusion practice

policies. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:403-06.

9/21/2010

5

Differing Views on the RBC

Transfusion Target

The Surgeons View - Developed 11 Policies

Transfusion needs should be assessed on case-by-case basis

Blood should be transfused 1 unit at a time

Limit allogeneic exposure g p

Transfusion trigger on a sliding scale, patient-specific

Perioperative blood loss prevented or controlled

Consider autologous alternatives

Maximize oxygen delivery to surgical patient

RBC mass increased or restored (e.g., use of Fe

+2

or EPO)

Document reasons for and results of transfusion

Hospital transfusion policies developed cooperatively & reassessed

regularly

Spence RK. Blood Management Practice Guidelines Conference. Surgical red blood cell

transfusion practice policies. Am J Surg. 1995;170(suppl. 6A):3S-15S.

Differing Views on the RBC

Transfusion Target

The Anesthesiologists View

[Hgb] is an inappropriate basis... for transfusion

Promulgated 6 g / dL as reasonable laboratorytrigger

Additional Influences urging decision to transfuse RBC

Patients cardiopulmonary reserve

The rate and magnitude of blood loss

Oxygen consumption

Atherosclerotic disease

ASATask Forces Practice Guidelines for Perioperative Blood Transfusion

and Adjuvant Therapies. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:198-208.

Developing Transfusion Targets: Incorporating

Laboratory Trigger Numbers & Clinical J udgment

9/21/2010

6

Developing Transfusion Targets:

Incorporating Clinical Judgment

Duration of anemia

Ongoing indication of organ ischemia

Patients intravascular volume

Normovolemic anemia well-tolerated

Potential or actual ongoing bleeding (rate and

magnitude)

Patients risk factors for complications of

inadequate oxygenation

Low cardiopulmonary reserve

High oxygen consumption

Who is At Risk from Intravascular

Volume Depletion?

Myocardial Ischemia

Coronary artery disease

V l l h t di Valvular heart disease

Congestive heart disease

Cerebral Ischemia

History of TIAs

Previous thrombotic stroke

Heberts Randomized, Controlled

Study in Critical Care

Studied 838 euvolemic ICU patients admitted with

[Hgb] <9.0 g/dL

418randomlyassignedtorestrictive transfusionarm 418 randomly assigned to restrictive transfusion arm

RBC transfused only when [Hgb] fell <7.0 g/dL

RBC maintained between 7 - 9 g/dL

420 assigned to liberal transfusion arm

RBC transfused only when [Hgb] fell <10.0 g/dL

RBC maintained between 10.0 - 12.0 g/dL

Hebert PC, et al. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(6):409-17.

9/21/2010

7

Heberts Randomized, Controlled

Study in Critical Care

Study Variable % in Restrictive

Transfusion Arm

% in Liberal

Transfusion Arm

In-Hospital Mortality

Rate

22.2 28.2 (p=0.05)

APACHE <20 8.7 16.1 (p =0.03)

Age<55 years 5.7 13.0 (p =0.02)

30-day mortality 18.7 23.3 (p =0.11)

Clinically significant

cardiac disease

20.5 22.9 (p =0.69)

Blood Transfusion in Elderly

Patients with Acute MI

Retrospective study

78,974 Medicare beneficiaries, > 65 years old

Hospitalized with AMI Hospitalized with AMI

Categorized according to hematocrit on admission

Questioned an association between use of

transfusion and 30-day mortality

Found RBC transfusion decreased 30-day mortality

in elderly patients with MI

WuW-C, et al., N Engl J Med. 2001;345(17):1230-36.

Association of Blood Transfusion with 30-Day

Mortality in Elderly AMI Patients, by Hct

9/21/2010

8

Blood Transfusion in the Elderly with

Acute Myocardial Infarction

Data indicate a high prevalence of anemia among elderly

with AMI (43% had Hct < 39%)

Anemic patients had a higher 30-day mortality

Blood transfusion is effective in reducing short term

mortality rate among elderly, if their Hct is < 30.0% and

may be effective for patients with Hcts as high as 33.0%

Patients were less likely to receive transfusion if they

were white, had cardiac arrest, had a DNR order or who

had been admitted from nursing home

Relationship of Blood Transfusion &

Clinical Outcomes in Patients with ACS

Anemic patients with ischemic heart disease: Is

there definitive evidence to support transfusing

RBC?

Are we doing harm to such patients if we fail to

transfuse for Hgb < 10 g / dL?

Post hoc analysis of pooled data from 3 large Post hoc analysis of pooled data from 3 large

international trials of patients with acute coronary

syndromes

Patients grouped as whether they received RBCs

transfusion during hospitalization or not

Of 24, 112 patients in 3 studies, 10% had at least 1

blood transfusion, complete data on transfusion &

bleeding and outcomes

RaoSV, et al., JAMA2004;292(13):1555-62

Blood Transfusion in Patients with ACS

GUSTO IIb Trial strategies to open occluded

arteries, heparin vs. hirudin

PURSUIT Trial Platelet GPIIb/IIIa suppression

using Integrilin (eptifibatide)

PARAGON B Lamifiban vs. placebo

All 3 trials treated with aspirin in (80 to 325 mg/dL)

Transfusion data collected prospectively in each

Endpoints:

30-day all-cause mortality

30-day death or MI

Moderate bleeding not life threatening, required

transfusion; only 1

st

bleeding episode included in analysis

9/21/2010

9

Relationship of Blood Transfusion &

Clinical Outcomes in Patients with ACS

Study Variable Transfusion

(medianof 3.6units/

transfusedpatient)

No transfusion

Age(yr)

Female(%)

68.9

41.5

64.0 (p <.001)

33.6 (p <.001) Female(%) 41.5 33.6 (p .001)

Black race(%)

Body weight (Kg)

Comorbidities (HTN, DM,

stroke, hyperlipidemia)

5.1

74.0

27.9

3.9 (p <.002)

77.3 (p <.001)

20.6 (p <.001)

Hematocrits (%),

baseline/ nadir

39.9 / 29.0 41.7 / 37.6

(p <.001)

30-day MI

30-day death or MI

25%

29%

8%(p <.001)

10%(p <.001)

Some Conclusions: Transfusion of

Patients with Ischemic Heart Disease

Transfused patients were 3.94 x more likely (OR 3.26

4.75) to die within 30 days

At Hct < 25%, there was no relation between

transfusion and death

Data suggest Hcts as low as 25% may be tolerated in

otherwise stable patients with ischemic heart disease

Discrepancies vs. Wu, et al data:

Admitting Hcts vs. developing anemia (drivers of anemia such

as bleeding and procedures)

Transfusion data probably incomplete

Excluded patients younger than 65 years of age

Excluded patients dying within 48 hours

Pre-Op Hct & Post-op Outcomes in Older

Patients undergoing Noncardiac Surgery

Retrospective cohort study (132 U.S. VA Medical Centers)

310, 311 veterans, aged 65 years old

Underwent major noncardiac surgery, 1997 2004

St tifi d ti t di t ti h t it Stratified patients according to preoperative hematocrit

Outcome Measures:

30-day postoperative mortality

30-day composite postoperative mortality or cardiac events

Found 30-day mortality and cardiac event rates increased

monotonically (+ or -) with deviations from normal Hct

WuW-C, et al., JAMA2007;297(22):2481-88.

9/21/2010

10

Baseline Patient Characteristics by

Preoperative Hematocrit Level

Hematocrit, %

<39.0 39.0 53.9 >53.9

N =132, 970 N =176, 704 n =637

42.8% 56.9% 0.2%

Mean age ~ 73 y/o

Ca. 98% male; ca. 80% Caucasian

Cohort with anemia had the most female & nonwhite patients, the highest

prevalence of DM, cardiac disease, renal disease, infected wounds cancer and

preoperative transfusions

30-Day Postoperative Mortality &

Cardiac events by Hct Level

Hct, %

30-Day Mortality

Rates, %

30-Day Cardiac

Event Rates, %

Adjusted Odds

Ratio

< 18.0 35.4 14.6 2.42

18.0 20.9 26.8 8.6 1.68

24 0 26 9 14 9 4 4 1 33 24.0 26.9 14.9 4.4 1.33

30.0 32.9 8.4 3.1 1.21

36.0 38.9 3.5 1.8 1.12

45.0 47.9 1.5 0.9 1 (Ref.)

48.0 50.9 1.8 1.0 1.12

51.0 53.9 3.1 1.4 1.42

54 5.6 2.9 1.55

Issues Raised by the Wu Hct-

Surgery Study in the Elderly

Work highlights strengths of using high quality, large

observational databases

Allows for adjustments of many potentially

confounding variables common to surgical practice

The etiology and chronicity of abnormal Hcts could

not be related to the outcomes

No causality claimed, but authors provide several

classic lines of cause-effect relationship:

An appropriate temporal relationship

A strong association of predictor and outcome

An apparent dose-response relationship

Biologic plausibility related to cardiac physiology

9/21/2010

11

Issues Raised by the Wu Hct-

Surgery Study in the Elderly

Epidemiologic features speak to a real relationship between

Hct and outcome

Defining anemia in the elderly may have important clinical

implications p

Is anemia simply a marker of other conditions that confer

increased risk?

National guidelines recommend treatment only when Hct is <

18% to 21%; the majority of deaths are associated with only

modest degree of anemia (Hct 27.0% - 38.9%)

If anemia were a modifiable risk factor, should preoperative

transfusion be considered?

Systematic Review of RBC

Transfusion in the Critically Ill

45 studies with a median of 687 patients per study

Outcome measures

Mortality

Infection

MOF Syndrome

ARDS

Risks of RBC transfusion outweighed benefits in

42 of 45 studies!!

Marik &Corwin, Crit Care Med 2008;36(9):2667-74.

Association of Transfusion &

Risk of Death

Marik & Corwin, Crit Care Med 2008;36(9):2667-74.

9/21/2010

12

Association of Transfusion &

Risk of Infectious Complications

Marik & Corwin, Crit Care Med 2008;36(9):2667-74.

Association of Transfusion

& Risk Developing ARDS

Marik & Corwin, Crit Care Med 2008;36(9):2667-74.

Settings Wherein RBC Transfusion

Appears to be Beneficial

Neonates, especially premature neonates

Massive transfusion

Battlefield casualties

T ( i ili ) Trauma (civilian)

Surgery

Obstetrical hemorrhage

Liver transplantation

Chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression,

and stem cell transplantation

Sickle cell disease (selected indications)

9/21/2010

13

Reality Testing of the RBC

Transfusion Trigger

Hemoglobin Level

(g/dL)

Transfusion Decision

> 10

RBCs usually unnecessary

6 - 10

Grey Zone: Clinically correlate &

individualize

< 6

Almost always transfuse

3

Life-threatening

DO NOT Transfuse Red Blood Cells

To improve general well-being

To promote wound healing

In place of a hematinic In place of a hematinic

Prophylactically, in the absence of signs,

symptoms or risks

For volume expansion, when oxygen-

carrying capacity is adequate

Comments

about about

Platelets

9/21/2010

14

Flavors of Platelet

Concentrates

Random-donor pools

(pool size as low as 4)

Apheresis platelets

( single donor ) ( g )

Pre-Storage RD Pools

(leukoreduced,

bacteriologically tested,

counted for yield)

Apheresis platelets,

stored in InterSol, a

platelet additive solution

Platelet Concentrates

All platelet

concentrates have a

5-day Shelf Life

All Adult Doses

have a minimum

count of 3 x 10

11

platelets

Crossmatched and

HLA-typed platelets

are Apheresis, by

definition

Prophylactic Platelet Transfusion Dose

1271 patients with hypoproliferative

thrombocytopenia

Transfusion Trigger=10,000 / L

Randomly assigned to 3 doses

1.1 x 10

11

/ meter

2

2 2 x 10

11

/ meter

2

Slichter, et al.,NEJM 2010;362(7): 600-13

2.2 x 10 / meter

4.4 x 10

11

/ meter

2

Low dose led to decreased numbers

of platelets transfused, but increased

transfusions given

Doses between 1.1 and 4.4 x 10

11

/

meter

2

had no effect on the incidence

of bleeding

9/21/2010

15

When You Think You are Observing

Platelet Refractoriness

Rule out clinical causes

DIC states

Sepsis, infection, fever

Splenomegaly Splenomegaly

Medications

Repeat platelet counts 10 30 minutes,

posttransfusion

Please order a Panel Reactive Antibody Assay!

Request specialized platelets only in the setting of

documented immune-mediated refractoriness

Deciding to Transfuse Platelets:

Risk Assessment Issues

Medical vs. Surgical patient

Bleeding vs. Non-bleeding

Risks in surgical / obstetric patients g p

Type / extent of surgery

Ability to control bleeding

Actual / anticipated rate of bleeding

Factors affecting platelet function, such as

medications, extracorporeal circulation

such as bypass, renal failure, etc.

Bleeding Risks & Platelet Count are

Approximately Correlated

Platelet Platelet Count (10 Count (10

99

/L) /L)

< 5

Likelihood of Spontaneous

Hemorrhage

High

5 10

10- 50

> 50

Increased with

Trauma

Surgery

Ulceration

Variably Increased

Exceedingly Unlikely

9/21/2010

16

Recommendations for

Platelet Transfusion

Platelet Platelet Count (10 Count (10

99

/L) /L)

< 5

10 20

Transfusion Decision

Almost Always

Prophylaxis Window 10 20

< 50

50 - 100

100

Prophylaxis Window

for Medical Patients

Usually Indicated for Surgery &

Other Invasive Procedures

Based on Risk of Bleeding

Uncommonly Indicated: Consider

with known platelet dysfunction &

microvascular bleeding

Avoid Transfusing Platelets

In thrombocytopenia due to increased platelet

destruction (immune or microangiopathic)

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) p y p p p ( )

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)

Other microangiopathies (HUS, HELLP)

Platelet transfusion in these settings are rarely

indicated and usually ineffective You incur all

the risks, with little or no benefit

Fresh Frozen Plasma Unit

9/21/2010

17

Where in the Classical Cascade Do

the Coagulation Factors Belong?

Extrinsic Pathway

Factor I

Factor II

Intrinsic Pathway

Factors I, II, V

Factor VIII:C (also

ac o

Factor V

Factor VII

Factor X

Ag:vWF)

Factor IX

Factor X

Factor XI

Factor XII

Vitamin K-Dependent Factors

(all Synthesized in the Liver)

Factor II

Factor VII Factor VII

Factor IX

Factor X

Protein C

Protein S

Coagulation Factors

Factor Common Name Half-Life

I Fibrinogen 3 4 Days

II Prothrombin 2 3 Days

III Thromboplastin

Available fromvarious

tissues, suchas lung,

brain, kidney

IV Ionized Ca

++

Ubiquitous

V Ac-globulin

(proaccelerin)

12 36 hours

VI Nonexistent -

9/21/2010

18

Coagulation Factors

Factor Common Name Half-Life

VII

Proconvertin

(Prothrombin

Conversion Accelerator)

4 6 hours

VIIIC

Antihemophilic Factor

12 hours

IX

Christmas Factor

24 hours IX 24 hours

X

Stuart-Prower Factor

1 2 days

XI

Plasma Thromboplastin

antecedent

2 3 days

XII

Hagemans (contact)

factor

2 3 days

XIII

Fibrin Stabilizing Factor

(Profibrinoligase)

3 5 days

Plasma Components Available in the

United States other than FFP

24-Hour Plasma, known as FP24

Collected and separated from whole blood in

a time frame >8 hours, but <24 hours

F h lf lif i 1 h f Frozen shelf life remains 1 year, when frozen

at < 18

o

C

Use just like FFP

Delay time to freezing causes mild decrease

in activity of the labile Factors, V & VIII

84%of Factor VIII left after 8 hours; 64%after 24 hours

Plasma Components Available in the

United States other than FFP

Thawed Plasma

Stored at 1 6

o

C

Label change required after 24 hours

Used for up to 5 days (same indications as FFP)

Factor V and Factor VIII are labile and

progressively decrease over time

Hemostatic levels of FV & FVIII still available

9/21/2010

19

Clinical Indications for

Plasma Transfusion

Multiple factor deficiency with active

bleeding or prior to invasive procedure, and

Documented laboratory evidence of

ProlongedPT or PTT (15xmidpoint of thereference Prolonged PT or PTT (1.5 x midpoint of thereference

range)

Low Fibrinogen level

Low specific coagulation factor assay(s)

Typical clinical situations include

Liver disease

DIC states

Massive hemorrhage & transfusion in trauma

Clinical Indications for

Plasma Transfusion

Plasma exchange replacement fluid for

treating microangiopathies (such as

TTP, HUS, HELLP syndrome)

Documented congenital or acquired

coagulation factor deficiency

Deficiency of Protein S, Protein C or AT

(formerly known as AT-III)

[AT and Protein C concentrates are

available in the US]

Clinical Indications for

Plasma Transfusion

Massive transfusion and evidence of both

Continued (microvascular) bleeding

C i fi i il bl / Coagulation deficiency or unavailable PT / aPTT

Urgent reversal of Coumadin effect

To stop Coumadin-therapy related intracranial bleeding)

[Prior to surgery or other invasive procedure]

(Frequently done, but remains controversial!)

9/21/2010

20

Misuses of Plasma Transfusion

As a volume expander

As a nutritional source

Toenhancewoundhealing To enhance wound healing

Not a suitable source of immunoglobulins (in

patients with severe hypogammagloubulinemia)

Mild to moderate prolongation of PT or

aPTT prior to invasive procedures

Defining the INR

International Normalized Ratio =

(Patient PT / control PT )

ISI

, where ISI =

International Sensitivity Index

ISI, used by the local laboratory performing the PT

measurement determinedfor eachcommercial batch measurement, determined for each commercial batch

The ISI reflects the responsiveness of a given

thromboplastin to a reduction in Vitamin K-dependent

coagulation factors compared to WHO reference

material.

Highly sensitive thromboplastins (ISI ~1.0) are now

made by recombinant technology with defined

phospholipid content

Lab Screening Tests as a Trigger

to Transfuse Plasma

No increased risk of hemorrhage / oozing

if the PT / aPTT is no more prolonged than

1.3 X upper limit of reference range

NOT an

INR = 1.5

pp g

- or -

1.5 X midpoint of reference range

Abnormality Clinical Coagulopathy

9/21/2010

21

The INR of Fresh Frozen Plasma

The INR of FFP is 1.1

(range 0.9 to 1.3)

It is not surprising that

giving FFP has little

effect on minimally effect on minimally

elevated PTs

FFP will affect the INR

only when there is a

big difference between

the FFP and the

patients plasma

And What if Plasma is Transfused?

Mean change of 0.03

INR units / unit of FFP

transfused

Mildly abnormal PTs

just dont change much

with FFP transfusion

INRs above 3 have a INRs above 3 have a

more significant change

per unit of FFP

Mildly prolonged PT

values (13 17 sec) do

not correlate with RBC

loss

Only 10% of patients

had the PT re-checked

after transfusion!!

Holland, et al., Transfusion 2005;45:1234-5

An Analysis of the Literature

Normal vs. Abnormal Coagulation Tests

Pre-procedure

coagulation

tests are lousy

predictors of

who is going to

bleed

Prophylactic

plasma

transfusion does

not result in

fewer bleeding

events

J Segal, W Dzik, et al., Transfusion 2005;45 (9): 1413-25.

9/21/2010

22

CRYOPRECIPITATED AHF

Cold-insoluble portion of plasma processed from FFP

Plasma proteins not soluble at 1 - 6

o

C

Estimated Contents of Plasma

Factors in Cryoprecipitated AHF

Constituent Constituent

Fibrinogen

Approximate Content

150 mg (minimum)

Factor VIII:C

Von Willebrand Factor

Factor XIII

80 IU (minimum)

80 120 Units

40 60 IU

Cryoprecipitate:

Clinical Indications

Hypofibrinogenemia

E.g., in consumptive coagulopathies such as DIC

Isolated fibrinogen deficiency with active bleeding Isolated fibrinogen deficiency with active bleeding

or in patients at risk

vonWillebrands Disease or Hemophilia A (use only

when commercial concentrates are unavailable)

Fibrin surgical adhesive

Isolated Factor XIII deficiency

9/21/2010

23

Use of Blood Components: Use of Blood Components:

Dosage Considerations Dosage Considerations

Blood Component Blood Component

RBC RBC

Dosage: Goals

Variable Number of Units:

Reverse Symptomatic Anemia

Enhance Oxygen-carrying Capacity

Platelets Platelets

Plasma Plasma

Cryoprecipitate AHF Cryoprecipitate AHF

- Use Apheresis Platelets or Pools -

Provide 1Adult Dose at atime

(nominally 3x 10

11

platelet count):

To ReduceHighRisksof Bleeding

10 15 mL / Kg Body Weight: To

Achieve Hemostatic Levels

Provide 1 Adult Dose, pool of 5 units

To Replete Fibrinogen Level

What is Blood Management?

1

Blood management is an

evidence-based,

multidisciplinaryprocess that

isdesigned to promote the

optimal useof bloodproducts optimal use of blood products

throughout the hospital.

The goal of blood management

is ensure the safe and efficient

use of the many resources

involved in the complex process

of blood component therapy.

1

Boucher & Hannon, Pharmacotherapy 2007;27(10)

Blood Management

What is it?

The promotion of the appropriate use of blood

Improvement of patient outcomes by the

d t f bl d prudent use of blood

What is it not (but might include)

Bloodless Medicine

Bloodless Surgery

No Blood

9/21/2010

24

Why Blood Management?

Blood isa precious resource that saves lives

Blood is often in short supply

The number of eligible, willing blood donors is

dropping

The cost of blood continues to rise

The decision to transfuse remains unavoidably

unsafe, but some risks and complications may

be avoidable

Principles of Blood Management

Focus on the patients best interest: Patient-Centered

Grounded in scientific validation and evidence-based

practice

Use a multidisciplinary teamapproach p y pp

Physician-driven

Multidisciplinary and multi-professional

Effective

Achieve change through education & training

Must have an institutional commitment to excellence

Principles of Blood Management

Operational Issues

Risk reduction instituted in the preoperative setting

Restricting certain medications or nutritional

supplements

Restrictions appropriate for the surgical procedure

Use of surgical devices, medications and techniques

to reduce blood loss

Use of peri-operative blood salvage

Planned cooperation among multiple levels of care

9/21/2010

25

Do Not Pull That Transfusion Do Not Pull That Transfusion