Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Obesity and Nutritional Programmes in Schools From Romania - EN

Uploaded by

Ioana Pelin0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

27 views5 pagesobesity

Original Title

Obesity and Nutritional Programmes in Schools From Romania_EN

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentobesity

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

27 views5 pagesObesity and Nutritional Programmes in Schools From Romania - EN

Uploaded by

Ioana Pelinobesity

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

Obesity and nutritional programmes in schools from Romania

Dr. Ana-Maria Pelin

1

, Dr. Victorita tefanescu

1

, Dr. Costinela Georgescu

1

,

The authors above mentioned declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this article.

1. Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy - Dunarea de Jos University , Galati, cod 800338, Romania

Abstract

Purpose: to establish whether the nutritional programmes from the special schools for children with

neuropsychomotor deficiencies from Romania influence the prevalence of obesity compared to the children

attending mass schools. The survey unfolded in the period October 2010 June 2011 and included 3.103 pupils

(age: 7-18 years): 663 from the special schools serving breakfast, lunch and a snack within the education institution

and 2.440 from mass schools that benefit only from the Fruit scheme in schools and Milk scheme in schools

programme of the EU. The percentage of obese children in the mass schools was of 8.97%, against 6.48% in the

special schools. Although the presence of the deficiency implies the existence of several risk factors for obesity,

contrary to expectations, we find a smaller number of obese within the children from the special schools. The

nutritional programmes that should be rethought from the perspective of introducing them in all the school types,

especially on quantitative standards.

Key words: nutritional programmes; obesity; neuropsychomotor deficiencies.

Correspondence mail:

Lecturer Dr. Ana-Maria Pelin , Galai 18 Saturn Str. - Romania;

E-mail: anapelin@gmail.com

1.Introduction

In the study made by Cynthia L. Ogden et al. (2012) it is stated that in the period 2009-2010 the prevalence of child

and teenager obesity was of 16.9%, unchanged percentage against 2007-2008. The prevalence of obesity to children

and teenagers aged 2 to 19 years was of 18.6% to the male sex and 15% to the feminine sex.

From the Report on Health Behaviour Research on the Children and Teenagers from Romania - Study HBSC/WHO

(2010), with information originating from 3 databases with 5,504 valid questionnaires: there results that the ratio of

those consuming daily breakfast varies between 34% and 54%, the daily fruit consumption drops significantly with

the age, for both boys and girls, the consumption of acidulous drinks within children remains yet very widespread,

over the average of the 42 HBSC countries (2005/2006), the consumption of sweets, chips and fries, is visibly

outlining as a food behaviour pattern favouring obesity. The behavioural modification occurs as necessary not only

among children but also parents, considering that young people perceive that they can obtain such products from

parents any time they want.

The school environment is of great importance for the development of the child as he spends a great portion of the

time at school (Papoutssi 2012) especially the children from the special education institutions serving meals within

the school.

Children with neuropsychomotor deficiencies falling under a special education form benefit in Romania from a

nutrition programme controlled and established under Order 1563 from 12

th

September 2008. According to this

order children with special needs benefit from two meals during a day and a snack: breakfast, snack and lunch.

There is under discussion the possibility to introduce controlled nutritional programmes in Romania also in mass

schools, especially for the children from disfavoured families.

There are controversies related to the efficiency of such programmes on the reduction of obesity among children, for

the creation of healthy nutritional habits and to reduce school abandonment.

At the moment, in Europe some initiatives are in progress, among them being the Fruit scheme in schools and Milk

scheme in schools of the EU.

For the first time in the last 15 years, National School Lunch Programme increased the nutrition standards. (D.

J.DeNoon 1012) USDA, the national agency supervising the two programmes School Breakfast Program (SBP) and

National School Lunch Program (NSLP), which are provided in schools, funded research projects related to these

programmes (Millimet, Tchernis, and Husain 2010). Research showed that these children participating to both

programmes, both breakfast and lunch, tend to be less overweight than those serving only lunch.

Howard and Prakash (2011) found evidence that pupils participating to the state-funded food programmes consume

more fruits, vegetables and natural juices than those serving meal in the family. They acquire a healthy food

programme that is maintained over a longer period of time than the schooling period. (Larry L. Howard 2011)

Obesity prevention in schools is a complex matter. Data suggests that a multidirectional approach is required in

order to have an impact. Nutritional education, food quality and contained macronutrients change, the increase of

physical activity as well as the support of the community and family are all important elements of this change ( J. E.

Lawton, 2012).

The interest for promoting healthy food and for the physical activity, called healthy life style, appeared as a reply

to the global obesity pandemic.( Vivica I Kraak 2009) IOM (The Institute of Medicine of the National Academy)

recommends food companies to use their creativity, resources and entire practical experience to promote and support

healthy food at children and teenagers ( JM McGinnis 2006).

2.Material and method

Research included a number of 3.103 children, their participation being freely consented, 2.440 from mass schools

and 663 from special schools for children with neuropsychomotor deficiencies. After correlating the BMI value

(body mass index) with the specific growth maps for age and sex according to the Centre for Disease Control -2000,

I have addressed a questionnaire to 202 from the total of 262 obese children (BMI percentile 95/+2DS/age/sex)

from the two types of schools: 30 (14.85%) are from special schools and 172 (85.14%) are from mass schools.

3.Results

Food behaviour

The average number of meals consumed daily by the obese children is not significantly different at those with

psychomotor deficiencies (2.93 0.52) compared with those without deficiencies (2.91 0,49) (t=0.25; GL=200;

p>0.05). Number of snacks: average snacks consumed daily by the obese children from special schools is

significantly higher (2.03 0.70) compared to those from normal schools (1.73 0.98) (t=2,03; GL=200; p<0,05).

Food consumed at breakfast: distribution of obese children depending on the main consumed aliments at

breakfast highlight the following aspects:

- Most frequently at breakfast diary is consumed, both by the group of obese children without deficiencies

(42.4%) and the children with neuropsychomotor deficiencies (46.7%);

- Bread is consumed by both investigated groups by 33-35%;

- Sandwich consumption is around 25% for both groups;

- Cold cuts cosumption is slightly more frequent at the children with deficiencies (33.3% vs 22.7%);

- Cereals are frequently consumed in the morning by around 30% of both obese children categories.

Food consumed at lunch: the distribution of the children from the study lot depending on the main consumed

food at lunch highlight the following aspects:

- Borsch is mostly consumed at lunch by both the obese children without deficiencies (42.4%) but

especially by the children with deficiencies (60%);

- Children from both groups frequently consume roasted meat but especially children with

neuropsychomotor deficiencies (33.3% vs 18.6%);

- Potatoes consumption at lunch is more frequently encountered at the obese children from normal schools

(21.5% vs 16.7%);

- It is noticeable that the desert is significantly more frequently consumed by the lot of obese children from

the special schools compared to the ones from the normal schools (16.7% vs 4.7%).

Food consumed at dinner: food inquiry shoed that the main food consumed at dinner is:

- At the group of obese children with neuropsychomotor deficiencies potatoes are mostly consumed at

dinner (30%);

- Children of both groups frequently consume diaries (23.3% vs 26.7%);

- Borsch consumption (23.3% vs 4.1%) and boiled vegetables (23.3% vs 9.3%) are significantly more

frequent at dinner within the group of obese children with neuropsychomotor deficiencies and also, at the

children with neuropsychomotor deficiencies it has been noticed a more frequent consumption at dinner

of eggs (23.3% vs 5.8%) and desert (9.20% vs 2.3%);

- It is also noticeable the fact that at the group of obese children from special schools salad is not

consumed at dinner.

The distribution of obese children from special schools who prefer roasted food was significantly

higher (p=0.004) (73.3% vs 43%), representing for this category, compared to the obese without

deficiencies, at relative risk of overweight 1.70 times higher (RR=1.70; IC95%: 1.292.25). Boiled food

is preferred by 47.7% within the normal schools obese children group and by 53.5% within those from

the special schools, distribution that doesnt have statistically significant differences (p=0.708).

The distribution of children preferring grill was significantly higher at the obese children from normal

schools (82% vs 63.3%) (p=0.038).

From the main food consumed more often the following consumptions are mainly highlighted:

- Cut colds are frequently consumed by both obese children with deficiencies (56.7%) as well as by those

without deficiencies (39%), half of them 1-2 times per week;

- Butter or margarine are consumed around 40% by the obese children with deficiencies and 18.6%

without deficiencies, most often 1-2 times per week (26.7% vs 11%);

- Cream consumption is encountered with approximately the same frequency at both studied groups

(23.8% vs 23.3%);

- Fat meat, pasta and processed cheese are also more frequently consumed by the obese children with

deficiencies, without statistically significant differences (table no. 1).

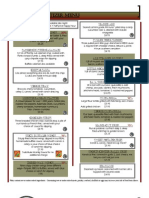

Table no. 1. Consumption frequency of the most used food by obese children

Weekly

frequency

w/o deficiency with deficiency w/o deficiency with deficiency

n % n % n % n %

Food Cold cuts Butter/margarine

1-2 times 33 19.2 8 26.7 19 11.0 8 26.7

3-4 times 16 9.3 3 10.0 5 2.9 4 13.3

5+ times 18 10.5 6 20.0 8 4.7 0 0

Total 67 39.0 17 56.7 32 18.6 12 40.0

p 0.747 0.110

Food Cream Fat meat

1-2 times 28 16.3 4 13.3 6 3.5 2 6.7

3-4 times 9 5.2 3 10.0 3 1.7 3 10.0

5+ times 4 2.3 0 0 4 2.3 1 3.3

Total 41 23.8 7 23.3 13 7.6 6 20.0

p 0.399 0.493

Food Pasta Processed cheese

1-2 times 3 1.7 2 6.7 28 16.3 7 23.3

3-4 times 1 0.6 1 3.3 8 4.7 4 13.3

5+ times 0 0 0 0 10 5.8 2 6.7

Total 4 2.3 3 10.0 46 26.7 13 43.3

p 0.546 0.555

The consumption of tomatoes and carrots exceeds 60% at both categories of obese children. At the children

with deficiencies associated with obesity, the distribution of the subjects consuming integral milk was of 84.2%,

significantly more frequently than the group of obese children without deficiencies, where the ratio of integral milk

consumption was of 51.3% (

2

=8.31; GL=2; p=0.016)

Most frequent desert consumption displayed the following characteristics at obese children with deficiencies

compared to the ones without deficiencies:

- Chocolate consumption was recorded most frequently at both study lots (30.2% vs 23.3%);

- Biscuits consumption was more frequent at the children with deficiencies (26.7% vs 14.5%), while the

consumption of cookies is noticed at the group of children without deficiencies (22.1% vs 13.3%);

- Fruits are preferred by 23.3% of the obese children with deficiencies and only by 11% by the children

without deficiencies;

- Ice cream is slightly more frequently consumed by the children without deficiencies (12.2% vs 6.7%)

(Table no. 2).

Table no. 2. Desert consumption frequency at obese children

Sweets Obese w/o deficiencies Obese with deficiencies

2

p

n % n %

Biscuits 25 14.5 8 26.7 1.93 0.164

Cookies 38 22.1 6 13.3 0.07 0.798

Fruits 19 11.0 7 23.3 0.01 0.909

Chocolate 52 30.2 7 23.3 2.43 0.119

Candies 20 11.6 2 6.7 0.24 0.626

Pie 19 11.0 3 10.0 0.02 0.883

Ice cream 21 12.2 2 6.7 0.33 0.568

Wafers 8 4.7 3 10.0 0.57 0.450

The distribution of obese children with deficiencies consuming sugar free juices was of 16.7%, slightly higher

compared to those without deficiencies (9.9%) (p=0.434).

Natural juices are preferred by 20.3% of the obese children without deficiencies and by 10% of those with

deficiencies, a distribution that is not statistically significant (p=0.228).

The distribution of children consuming acidulous beverages with sugar was of 66.7% at the group of obese

children with deficiencies (66.7 % vs 43.6%), distribution revealing a 1.53 times higher obesity risk (RR=1.53; IC

95%: 1.132.07).

4. Discussions

Our survey is comparing two lots, belonging to two different types of schools and reaches the conclusion that,

although in the lot of the children with neuropsychomotor deficiencies the number of obesity risk factors is higher

they have a smaller obesity percentage than the mass school children (6.48% compared cu 8.97%). The low obesity

prevalence in the special schools is due to the nutritional programmes these children benefit from. The comparative

analysis of the food behaviour shows there is no difference as to the number of meals between the two lots.

Although the consumption of hyper caloric food is higher in the group of special schools children (butter, margarine,

fat meat, pasta, processed cheese) they have a lower obesity percentage. Mass schools obese children prefer refined

sweets that are more expensive whereas in special schools they serve biscuits more frequently. Under these

circumstances represented by multiple risk factors for obesity and food consumption adequate to the age, but with a

higher ratio of hyper caloric food, the children with deficiencies have less prevalent obesity. It seems a re-

assessment is required for order 1563/12

th

September 2008 regulating the food consumption in schools before

introducing national scale nutritional programmes, or rather a more rigorous compliance with the nutrition

standards.

The children with neuropsychomotor deficiencies represent a special category with special needs. Romania, after

1989, records a series of changes in all sectors and services, including the field of the care of persons with special

needs. The fact that our country is now part of the European Union implies a series of obligations, norms and laws

that have been adopted and need to be abided by, yet all these need to be adapted to the specifics of our country.

There are not allotted enough funds, there are not enough specialists (kinetotherapists, social assistants, medics,

psychologists, psychiatrists, institutors etc.), there is no plan of developing and improving the services system

intended to those with special needs, which should be coherent and well constructed, applied to the real current

problems (Bonea G.V. 2011).

Works Cited

Bonea G.V., "Practical aspects of public protection for child with disabilities," CALITATEA VIEII, XXII, nr. 1, p. p.

83102, 2011.

D. J.DeNoon, "USDA Issues New School Lunch Nutrition Standards," January 2012. [Online].

J. E. Lawton, "Obesity Prevention in Schools: Implications for Nursing," 25 04 2012. [Online]. Available:

http://hdl.handle.net/2376/3432 .

JM McGinnis, Institute of Medicine Food Marketing to Childrenand Youth: Threat or Opportunity?, Washington,

DC: The NationalAcademies Press, 2006

Larry L. Howard, Nishith Prakash"Do school lunch subsidies change the dietary patterns of children from low-

income households? Contemporary Economic Policy,Volume 30, Issue 3, pages 362381, July 2012

Millimet, D.L., Tchernis, R. and Husain, M., "School nutrition programs and the incidence of childhood obesity,"

The Journal of Human Resources, pp. 640-564, 2010.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. "Prevalence of Obesity and Trends in Body Mass Index Among US

Children and Adolescents," JAMA, vol. 307(5), pp. 483-490, 2012.

Papoutsi Georgia S, Andreas C. Drichoutis, Rodolfo M. Nayga, Jr, "THE CAUSES OF CHILDHOOD OBESITY:

A SURVEY;," Journal of Ecomonic Surveys, 12 JANUARY January 2012.

Vivica I Kraak, Shiriki K Kumanyika and Mary Story, "The commercial marketing of healthy lifestyles to address

the global child and adolescent obesity pandemic: prospects,pitfalls and priorities. Public Health Nutrition, Volume

12 / Issue 11 / November 2009, pp 2027-2036

.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Yorkshire college foreign student course applicationDocument1 pageYorkshire college foreign student course applicationIoana PelinNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- LETTERDocument1 pageLETTERIoana PelinNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Letter 2Document1 pageLetter 2Ioana PelinNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Is Tourism The Plague of Culture and HistoryDocument1 pageIs Tourism The Plague of Culture and HistoryIoana PelinNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Letter 3Document1 pageLetter 3Ioana PelinNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Rezumate CNR 2019Document182 pagesRezumate CNR 2019Ioana PelinNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Fast Track - 11-14 KeyDocument2 pagesFast Track - 11-14 KeyIoana PelinNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Advanced Grammar 71-116 - Practice Test - KeyDocument5 pagesAdvanced Grammar 71-116 - Practice Test - KeyIoana PelinNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- GrammarDocument6 pagesGrammarIoana PelinNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- Pe Perioada: 01-01-2022 - 27-01-2022 EXTRAS DE CONT Nr. 1 Din Data: 27-01-2022Document2 pagesPe Perioada: 01-01-2022 - 27-01-2022 EXTRAS DE CONT Nr. 1 Din Data: 27-01-2022Ioana PelinNo ratings yet

- TEST - Upstream Proficiency UNITS 1-5 I. Fill in The Blanks With ONE Word Only (Sometimes, The First Letter Is Given)Document2 pagesTEST - Upstream Proficiency UNITS 1-5 I. Fill in The Blanks With ONE Word Only (Sometimes, The First Letter Is Given)Ioana PelinNo ratings yet

- StudyingDocument1 pageStudyingIoana PelinNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Harry Potter and The PhilosopherDocument1 pageHarry Potter and The PhilosopherIoana PelinNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Obesity and Nutritional Programmes in Schools From Romania - ENDocument5 pagesObesity and Nutritional Programmes in Schools From Romania - ENIoana PelinNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Imaging of Ewing's Sarcoma: Jen SonDocument26 pagesImaging of Ewing's Sarcoma: Jen SonIoana PelinNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Anatomo-Radioimaging Correlation in Atypical Ewing SarcomaDocument5 pagesAnatomo-Radioimaging Correlation in Atypical Ewing SarcomaIoana PelinNo ratings yet

- Nutrition For Toodler and Pre School Children Dr. Mei NeniDocument78 pagesNutrition For Toodler and Pre School Children Dr. Mei Neningsukma7382No ratings yet

- Experiment No: 6 Expirement Title: Preparation of 2-Hexanol From 1-HexeneDocument5 pagesExperiment No: 6 Expirement Title: Preparation of 2-Hexanol From 1-HexeneMoemedi Moshakga40% (5)

- U.S. Dairy Ingredients in Yogurt and Yogurt BeveragesDocument20 pagesU.S. Dairy Ingredients in Yogurt and Yogurt BeveragesNguyễn Tiến DũngNo ratings yet

- Departure 191-200Document45 pagesDeparture 191-200Donela Joy AbellanoNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- National Programme for Prevention and Control of Fluorosis GuidelinesDocument45 pagesNational Programme for Prevention and Control of Fluorosis GuidelinesAADITYESHWAR SINGH DEONo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Beer HandbookDocument11 pagesBeer HandbookPadam Singh0% (1)

- Lead & Copper Monitoring Results For Last 3 YearsDocument124 pagesLead & Copper Monitoring Results For Last 3 YearsFOX 5 DCNo ratings yet

- Customs and Traditions of IndonesiaDocument16 pagesCustoms and Traditions of IndonesiaJunior PayatotNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Archaeomagnetic Evidence of Pre-Hispanic Origin of MezcalDocument8 pagesArchaeomagnetic Evidence of Pre-Hispanic Origin of MezcalCarlos F LNo ratings yet

- Feasibility Study Cybernique CafeDocument13 pagesFeasibility Study Cybernique CafeDexter Lacson OrarioNo ratings yet

- Womens Health India March 2014Document124 pagesWomens Health India March 2014NishimaNo ratings yet

- Techniques, Tips and Recipes: Soda FiringDocument21 pagesTechniques, Tips and Recipes: Soda FiringCristiane SouzaNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Vitaman WaterDocument24 pagesVitaman WaterMurtaza HussainNo ratings yet

- Bamberg Rauch Liquid Malt Extract Specification (1) - WeyermannDocument2 pagesBamberg Rauch Liquid Malt Extract Specification (1) - WeyermannCarmineD'AnielloNo ratings yet

- Science4 - 1st QTR - Mod 3 - MixDocument42 pagesScience4 - 1st QTR - Mod 3 - MixJAYDEN PAULO CASTILLONo ratings yet

- 2A E3 Extra Part II (1) 1111111Document2 pages2A E3 Extra Part II (1) 1111111Pyerry MarinhoNo ratings yet

- Types of LabelsDocument22 pagesTypes of LabelsTarunMishra100% (2)

- Assignment 2 Front Sheet: 18 September 2021Document44 pagesAssignment 2 Front Sheet: 18 September 2021Nguyễn Tăng Quốc BảoNo ratings yet

- Kaiser Katalog Engl 2014Document39 pagesKaiser Katalog Engl 2014mmm_gggNo ratings yet

- Ing Ed ClauseDocument3 pagesIng Ed ClauseHoàng AnhNo ratings yet

- 3 Day Cleanse Meal Plan FINAL RGBDocument16 pages3 Day Cleanse Meal Plan FINAL RGBMichael SanchezNo ratings yet

- ABI's History as the Philippines' Leading Beverage CompanyDocument15 pagesABI's History as the Philippines' Leading Beverage CompanyJon SagabayNo ratings yet

- The Induction ProcessDocument5 pagesThe Induction ProcessP Kranthi KiranNo ratings yet

- June Party - Festa Junina - Revista MaganewsDocument5 pagesJune Party - Festa Junina - Revista MaganewsKarine TiepoNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Arby's Nutrition InfoDocument8 pagesArby's Nutrition InfoJody Ike LinerNo ratings yet

- Past-Perfect-Past-Tense - My HomeworkDocument1 pagePast-Perfect-Past-Tense - My HomeworkNewspaper Translation with Mr. HongNo ratings yet

- Slyman S Restaurant MenuDocument3 pagesSlyman S Restaurant MenueatlocalmenusNo ratings yet

- Yakima Sports Center Menu 2009Document4 pagesYakima Sports Center Menu 2009Phie FiaNo ratings yet

- WorldofeastereggsDocument7 pagesWorldofeastereggsapi-265783879No ratings yet

- MGT Report AFBL PDFDocument20 pagesMGT Report AFBL PDFx100% (1)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- The Diabetes Code: Prevent and Reverse Type 2 Diabetes NaturallyFrom EverandThe Diabetes Code: Prevent and Reverse Type 2 Diabetes NaturallyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)