Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jaundice Heart Failure

Uploaded by

Ganda Edhi0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

42 views3 pagesOn rare occasions the first manifestation of heart disease is jaundice. Caused by passive congestion of the liver or acute ischaemic hepatitis. 8 patients (1.2%) had a primary cardiac cause for their jaundice. All had dyspnoea, an increased cardiothoracic ratio on chest x-ray and an abnormal electrocardiogram.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentOn rare occasions the first manifestation of heart disease is jaundice. Caused by passive congestion of the liver or acute ischaemic hepatitis. 8 patients (1.2%) had a primary cardiac cause for their jaundice. All had dyspnoea, an increased cardiothoracic ratio on chest x-ray and an abnormal electrocardiogram.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

42 views3 pagesJaundice Heart Failure

Uploaded by

Ganda EdhiOn rare occasions the first manifestation of heart disease is jaundice. Caused by passive congestion of the liver or acute ischaemic hepatitis. 8 patients (1.2%) had a primary cardiac cause for their jaundice. All had dyspnoea, an increased cardiothoracic ratio on chest x-ray and an abnormal electrocardiogram.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

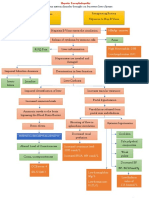

Jaundice as a presentation of heart failure

R van Lingen MRCP

2

U Warshow MRCP

1

H R Dalton DPhil FRCP

1

S H Hussaini MD FRCP

1

J R Soc Med 2005;98:357359

SUMMARY

On rare occasions the rst manifestation of heart disease is jaundice, caused by passive congestion of the liver or

acute ischaemic hepatitis. We looked for this presentation retrospectively in 661 patients referred over fty-six

months to a jaundice hotline (rapid access) service. The protocol included a full clinical history, examination and

abdominal ultrasound. Those with no evidence of biliary obstruction had a non-invasive liver screen for

parenchymal liver disease and those with suspected heart disease had an electrocardiogram, chest X-ray and

echocardiogram.

8 patients (1.2%), bilirubin 3179 m mmol/L, mean 46 m mmol/L, had a primary cardiac cause for their jaundice. All had

dyspnoea, an increased cardiothoracic ratio on chest X-ray and an abnormal electrocardiogram. The jugular venous

pressure was raised in the 3 in whom it was recorded. In 6 patients the jaundice was attributed to hepatic

congestion and in 2 to ischaemic hepatitis. All patients had severe cardiac dysfunction.

Jaundice due to heart disease tends to be mild, and a key feature is breathlessness. The most common

mechanism is hepatic venous congestion; ischaemic hepatitis is suggested by a high aminotransferase.

INTRODUCTION

Jaundice is an uncommon presentation of cardiac disease.

13

The two major causes are chronic congestion due to heart

failure and ischaemic hepatitis from acute circulatory

impairment. We conducted a retrospective review of

patients seen at a jaundice hotline service to determine the

proportion of such cases and their clinical characteristics.

METHODS

The Royal Cornwall Hospital is a district general hospital

serving a population of about 400 000. A hotline service

was started in November 1998 to facilitate rapid diagnosis

and treatment of patients with jaundice in the community,

and the initial results have been reported.

4

All patients had a

full history taken for alcohol use, medications and risk

factors for viral hepatitis. An abdominal ultrasound was

performed to identify biliary obstruction. In patients

without biliary obstruction, blood was tested for evidence

of virus infections (hepatitis A, B and C, EpsteinBarr,

cytomegalovirus), for autoantibodies and for alpha-1-

antitrypsin concentration, together with iron and copper

studies. In patients without evidence of biliary obstruction

or parenchymal liver disease, cardiac evaluation included an

electrocardiogram (ECG), an echocardiogram and a chest

X-ray.

RESULTS

Of 661 patients seen by the jaundice hotline service in fty-

six months 8 (1.2%) had a primary cardiac disorder. All

reported dyspnoea. Details are in Table 1. Their jaundice

was mild (bilirubin 3179 mmol/L, mean 46 mmol/L) and

only 2 had an alkaline phosphatase above normal. 2 patients

with severe cardiac failure and an alanine aminotransferase

exceeding 1000 iu/L were judged to have ischaemic

hepatitis. Both had a raised troponin, so the probable cause

of their cardiac decompensation was myocardial infarction

within the last 10 days; their liver function tests became

normal with treatment of their heart disease. All patients

had abnormal electrocardiograms, and echocardiograms

showed severe global or left ventricular impairment,

valvular abnormalities and in one case a left atrial myxoma.

The clinical assessment of jugular venous pressure was

recorded in only 3 of the 8 patients.

DISCUSSION

Among patients presenting via the hotline, heart disease was

a rare cause for jaundice. Moreover, the jaundice was always

mild. In all 8, the history of dyspnoea together with cardiac

enlargement on X-ray and ECG abnormalities pointed to the

underlying disorder. The jugular venous pressure, a bedside

assessment with diagnostic, therapeutic and prognostic

value,

4

was not well recorded in this series.

P

R

A

C

T

I

C

E

357

J O U R N A L O F T H E R O Y A L S O C I E T Y O F M E D I C I N E V o l u m e 9 8 A u g u s t 2 0 0 5

1

Cornwall Gastrointestinal Unit, Royal Cornwall Hospital Trust, Truro TR1 3LJ;

2

Department of Cardiology, Derriford Hospital, Plymouth PL6 8DH, UK

Correspondence to: Dr Hyder Hussaini

E-mail: hyder.hussaini@rcht.cornwall.nhs.uk

In 6 of the 8 patients the jaundice was probably due to

the passive liver congestion of low-output cardiac failure.

Other groups have described a raised alkaline phosphatase in

these circumstances

57

but this was seen in only 2 of the 6.

The phenomenon has been linked to the severity of

tricuspid regurgitation.

8,9

Suggested mechanisms for the

jaundice of low-output heart failure are decreased hepatic

blood ow, increased hepatic venous pressure and

decreased arterial oxygen saturation. In addition, work in

animals raises the possibility of endotoxin mediated

damage.

10

In the 2 patients with ischaemic hepatitis the probable

cause was myocardial infarction in the setting of severe

valvular disease. Such patients tend to have a massive rise in

aminotransferases with associated derangement in pro-

thrombin time.

11

Ischaemic hepatitis, which results from

hepatic circulatory failure, predominantly affects the

perivenular zone of the hepatic acinus.

2

Hepatic blood ow

declines by about 10% for every 10 mmHg drop in arterial

pressure.

12

Rapid resolution of the hypotension usually

leads to full recovery of the hepatitis.

12,13

It is noteworthy

that healthy individuals with acute hypotension from events

such as trauma do not seem to develop ischaemic hepatitis.

A retrospective analysis of patients with ischaemic hepatitis

indicated that all had underlying heart disease, predomi-

nantly right-sided.

14

Thus a baseline of hepatic congestion

may be required as a primer before the development of

ischaemic hepatitis.

We conclude that the combination of jaundice and

breathlessness should prompt a careful cardiological

examination, including assessment of the jugular venous

pressure, electrocardiogram, chest radiograph and echo-

cardiogram to exclude a cardiac cause. Ischaemic hepatitis is

suggested by a high alanine aminotransferase.

358

J O U R N A L O F T H E R O Y A L S O C I E T Y O F M E D I C I N E V o l u m e 9 8 A u g u s t 2 0 0 5

Table 1 Clinical details

Patient

(age)

Dyspnoea

duration JVP

Bilirubin

mmol/L

(ref. range

823)

ALT IU/L

(1044)

Alk phos

IU/L

(45122) Liver U/S ECG CXR Echo

M (54) 5 months : 33 41 99 Enlarged;

engorged

hepatic

veins

AF; partial

RBBB

Bilateral

pleural

effusions.

:C-th ratio

Left atrial

myxoma;

dilated RV

M (69) 1 month NR 51 50 82 Normal AF; LBBB Bilateral

pleural

effusions.

:C-th ratio

Dilated LV,

EF 15%

M (79) 1 month : 56 38 57 Dilated IVC

and hepatic

veins

LBBB :C-th ratio Dilated LV,

EF 18%

M (61) 3 months NR 33 25 111 Mild

parenchymal

irregularity

AF; LBBB :C-th ratio;

bibasal

shadowing

Dilated LV,

EF520%

M (72) 42 years

(known

cardiomyopathy)

NR 31 11 272 Normal AF; LBBB :C-th ratio Dilated LV,

EF 23%

F (69) 2 weeks NR 79 1213 887 Normal LBBB :C-th ratio Severe LV

i mpairment;

severe AS

M (80) 34 weeks NR 32 1085 141 Dilated hepatic

veins

AF;

partial

LBBB

:C-th ratio Severe MR;

normal LV

M (75) 1 month : 55 41 68 Incidental

single

gallstone

1st degree

heart

block;

LBBB

:C-th ratio Severe MR;

moderate

AS; mild LV

i mpairment

JVP=jugular venous pressure; ALT=alanine aminotransferase; alk phos=alkaline phosphatase; U/S=ultrasound; ECG=electrocardiogram; CXR=chest X-ray; IVC=inferior vena

cava; R/L BBB=right/left bundle branch block; AF=atrial brillation; c-th ratio=cardiothoracic ratio; RV, LV=right, left ventricle; EF=ejection fraction; AS=aortic stenosis;

MR=mitral regurgitation; NR=not recorded

REFERENCES

1 Giallourakis CC, Rosenberg PM, Friedman LS. The liver in heart

failure. Clin Liver Dis 2002;6:94767, viiiix

2 Neuberger J. The liver in systemic disease. In: Warrell DA, Cox TM,

Firth JD, Benz E, eds. Oxford Textbook of Medicine, 4th edn. Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 1993

3 Lowe MD, Harcombe AA, Grace AA, Petch MC. Restrictive

constrictive heart failure masquerading as liver disease. BMJ

1999;318:5856

4 Mitchell J, Hussaini H, McGovern D, Farrow R, Maskell G, Dalton H.

The jaundice hotline for the rapid assessment of patients with jaundice.

BMJ 2002;325:21315

5 Morrissey M, Durkin M, Gunnar R. The cardiovascular system. In:

Haubrich W, Schaffner F, Berk JE, eds. Bockus Gastroenterology, 5th edn.

Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1995:3392403

6 Braunwald E. Heart failure. In: Braunwald E, Fauci A, Kasper D,

Hauser S, Longo DL, Jameson JL, eds. Harrisons Principles of Internal

Medicine, 15th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001:131829

7 Kumar P, Clarke M. Clinical Medicine, 3rd edn. London: Baillie`re

Tindall, 1994

8 Finlayson ND, Bouchier IA. Diseases of the liver and biliary system. In:

Edwards CR, Bouchier IA, Haslett C, Chilvers ER, eds. Davidsons

Principles and Practice of Medicine, 17th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill

Livingstone, 1995:5523

9 Lau GT, Tan HC, Kritharides L. Type of liver dysfunction in heart

failure in relation to the severity of tricuspid regurgitation. Am J Cardiol

2002;123:136784

10 Cogger VC, Fraser R, Le Couteur DG. Liver dysfunction and heart

failure. Am J Cardiol 2003;91:1399

11 Givertz MM, Colucci WS, Braunwald E. Clinical aspects of heart

failure: high-output failure, pulmonary edema. In: Braunwald E, Zipes

P, Libby P, eds. Heart Disease: a Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine, 6th

edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2001

12 Dillon JF, Finlayson NDC. The liver in systemic disease. In: Shearman

DJC, Finlayson NDC, Camilleri M, Carter D, eds. Diseases of the

Gastrointestinal Tract and Liver. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1997

13 Ellenberg M, Osserman KE. The role of shock in the production of

central liver cell necrosis. Am J Med 1951;11:1708

14 Seeto RK, Fenn B, Rockey DC. Ischemic hepatitis: clinical

presentation and pathogenesis. Am J Med 2000;109:10913

359

J O U R N A L O F T H E R O Y A L S O C I E T Y O F M E D I C I N E V o l u m e 9 8 A u g u s t 2 0 0 5

You might also like

- Research Kolengioma SarkiomastosisDocument7 pagesResearch Kolengioma SarkiomastosisGanda EdhiNo ratings yet

- Research Myoma Uteri New EraDocument12 pagesResearch Myoma Uteri New EraGanda EdhiNo ratings yet

- Measuring Carboxyhemoglobin (HbCO) LevelsDocument21 pagesMeasuring Carboxyhemoglobin (HbCO) LevelsGanda EdhiNo ratings yet

- Gender Differences in Cardiovascular Response To Isometric Exercise in The Seated and Supine PositionsDocument7 pagesGender Differences in Cardiovascular Response To Isometric Exercise in The Seated and Supine PositionsGanda EdhiNo ratings yet

- KPBI 02 Lab - Man.ug (Reviisi01)Document14 pagesKPBI 02 Lab - Man.ug (Reviisi01)Ganda EdhiNo ratings yet

- HTTP SofaDocument1 pageHTTP SofaGanda EdhiNo ratings yet

- Senin, 10 Maret 2008 CDK PengelolaanpenderitadengankeluhanDocument1 pageSenin, 10 Maret 2008 CDK PengelolaanpenderitadengankeluhanGanda EdhiNo ratings yet

- ATS Statement on Dyspnea Mechanisms, Assessment and ManagementDocument20 pagesATS Statement on Dyspnea Mechanisms, Assessment and ManagementTrismegisteNo ratings yet

- Referensi Sabtu080308Document1 pageReferensi Sabtu080308Ganda EdhiNo ratings yet

- ReferensiDocument1 pageReferensiGanda EdhiNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument2 pagesDaftar PustakaGanda EdhiNo ratings yet

- Lab Activity PharmacoDocument3 pagesLab Activity PharmacoGanda EdhiNo ratings yet

- Daftar Kelompok 2007 Sem 5Document15 pagesDaftar Kelompok 2007 Sem 5Ganda EdhiNo ratings yet

- KLP Diskusi Blok BHL I Angk 2007Document7 pagesKLP Diskusi Blok BHL I Angk 2007Ganda EdhiNo ratings yet

- Absens IDocument4 pagesAbsens IGanda EdhiNo ratings yet

- Anafilaksisi Masa DepanDocument15 pagesAnafilaksisi Masa DepanGanda EdhiNo ratings yet

- Kelompok PraktikumDocument2 pagesKelompok PraktikumGanda EdhiNo ratings yet

- Jadwal BHL 1 - 2008Document1 pageJadwal BHL 1 - 2008Ganda EdhiNo ratings yet

- Note Taking & Power Reading 2010Document25 pagesNote Taking & Power Reading 2010Ganda EdhiNo ratings yet

- Promotion Best Star Cardiology FixDocument2 pagesPromotion Best Star Cardiology FixGanda EdhiNo ratings yet

- SGD 3 - 21 GramsDocument3 pagesSGD 3 - 21 GramsGanda EdhiNo ratings yet

- Bagaimana BerefleksiDocument6 pagesBagaimana BerefleksiGanda EdhiNo ratings yet

- Health, Stress, and CopingDocument17 pagesHealth, Stress, and CopingGanda EdhiNo ratings yet

- Pharmaco ToxicologyDocument49 pagesPharmaco ToxicologyGanda EdhiNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Biochemistry of Liver: Alice SkoumalováDocument37 pagesBiochemistry of Liver: Alice Skoumalováandreas kevinNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics: Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics PediatricsDocument2 pagesPediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics: Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics PediatricsBobet Reña100% (2)

- Treatment: Wilson DiseaseDocument4 pagesTreatment: Wilson Diseaseali tidaNo ratings yet

- SANDRA, Apollo OBG Minor Disorders in Neonates PPT - SECTION BDocument15 pagesSANDRA, Apollo OBG Minor Disorders in Neonates PPT - SECTION Bsandra0% (1)

- Cholestasis: DR I Gede Palgunadi Sppd-Finasim Fk-Unram/Rsup NTBDocument17 pagesCholestasis: DR I Gede Palgunadi Sppd-Finasim Fk-Unram/Rsup NTBMuzayyanatulhayat ARNo ratings yet

- Infectious Diseases EmqDocument24 pagesInfectious Diseases Emqfrabzi100% (1)

- Assessment of The Integumentary SystemDocument21 pagesAssessment of The Integumentary SystemSheila Mae Panis100% (1)

- Rosh ReviewDocument125 pagesRosh ReviewPrince Du100% (2)

- Newborn Assessment 2.16Document16 pagesNewborn Assessment 2.16rrbischofbergerNo ratings yet

- A Case On Periampullary Carcinoma.: Presented by DR Sumaiya Tasnim TanimaDocument34 pagesA Case On Periampullary Carcinoma.: Presented by DR Sumaiya Tasnim TanimaJobaer MahmudNo ratings yet

- Krok BukDocument242 pagesKrok BukLucja0% (1)

- A Case Report On Biliary AtresiaDocument2 pagesA Case Report On Biliary AtresiaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Report: FinalDocument10 pagesDiagnostic Report: FinalKushagra SahniNo ratings yet

- Kamara - Factors Associated With Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia in The First 2weeks of Life in OlaDocument56 pagesKamara - Factors Associated With Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia in The First 2weeks of Life in OlaJulia StantonNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia and The Hepatobiliary SystemDocument35 pagesAnesthesia and The Hepatobiliary SystemscribdNo ratings yet

- Icterus Neonatorum: (Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia)Document30 pagesIcterus Neonatorum: (Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia)Dian Vera WNo ratings yet

- Pedia ReviewerDocument27 pagesPedia ReviewerEvangeline GoNo ratings yet

- Case Study: Obstructive JaundiceDocument11 pagesCase Study: Obstructive JaundiceZhy CaluzaNo ratings yet

- Group B and A streptococcus differentiationDocument75 pagesGroup B and A streptococcus differentiationDjdjjd SiisusNo ratings yet

- Sella Modul TropisDocument34 pagesSella Modul TropissellasellaNo ratings yet

- IJRPR5933Document8 pagesIJRPR5933rifa iNo ratings yet

- Digestive System: Yousef Ali Sazan Falah Snor Dilan KawtharDocument21 pagesDigestive System: Yousef Ali Sazan Falah Snor Dilan Kawtharkauther hassanNo ratings yet

- PEDIA 20Idiot20Notes 1Document76 pagesPEDIA 20Idiot20Notes 1Aljon S. TemploNo ratings yet

- PD 17 To 21Document148 pagesPD 17 To 21Loai Mohammed IssaNo ratings yet

- Hepatic Enceph PathophysioDocument1 pageHepatic Enceph PathophysioJessica FabroaNo ratings yet

- Biochemistry 1Document32 pagesBiochemistry 1zaydeeeeNo ratings yet

- AST Practical Handout For 2nd Year MBBSDocument4 pagesAST Practical Handout For 2nd Year MBBSIMDCBiochemNo ratings yet

- Dis LiverDocument40 pagesDis LiverPrem MorhanNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Jaundice Bilirubin Physiology and ClinicaDocument13 pagesNeonatal Jaundice Bilirubin Physiology and ClinicaNURUL NADIA BINTI MOHD NAZIR / UPMNo ratings yet

- Study of Haematological Parameters in Malaria: Original Research ArticleDocument6 pagesStudy of Haematological Parameters in Malaria: Original Research ArticleV RakeshreddyNo ratings yet