Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Thesis Final Paper Rev 1

Uploaded by

Karlo Prado100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

217 views112 pagesBrand Equity of High Rise Residential Condos

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentBrand Equity of High Rise Residential Condos

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

217 views112 pagesThesis Final Paper Rev 1

Uploaded by

Karlo PradoBrand Equity of High Rise Residential Condos

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 112

!"# %#&'()*+,")-, .#(/##+ .0'+1 234)(56 .

0'+1 70#8#0#+9#6 '+1

7409"',# :+(#+( *8 70#;)4; %#,)1#+()'& <*+1*;)+)4; =+)(,

A 1hesls aper

resenLed Lo Lhe

MarkeLlng ManagemenL ueparLmenL

8amon v. del 8osarlo College of 8uslness

ue La Salle unlverslLy

ln arLlal lulflllmenL

Cf Lhe Course 8equlremenLs of Lhe uegree

MasLers of Sclence ln MarkeLlng

SubmlLLed by:

!osef karlo v. rado

1hesls Advlser: Mr. 8enlson ?. Cu, CM

AugusL 2013

1

APPROVAL SHEET

This thesis hereto entitled:

The Relationships Between Brand Equity, Brand Preference and Purchase Intent

of Premium Residential Condominium Units

prepared and submitted by Josef Karlo V. Prado in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Marketing has been examined

and is recommended for acceptance and approval for MSM Final Thesis Defense/

Oral Examination.

Mr. Benison Y. Cu, CPM

Adviser

Approved by the Committee on Oral Examination with a grade of PASSED on August

17, 2013.

Ms. Marie Julie B. Taada

Chair

Dr. Luz T. Suplico-Jeong Ms. Carmelita M. Walton

Member Member

Accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science

in Marketing

Dr. Maria Andrea L. Santiago

Dean, College of Business

2

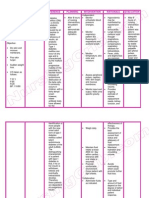

!'>&# *8 <*+(#+(,

!"#$%&' )* +,%'-./!%+-, 00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 1

)0)0 2#!34'-/,. -5 %"& 6%/.7 1

)080 -$&'#%+-,#9 .&5+,+%+-, -5 %&':6 ;

)0<0 %"&-'&%+!#9 5'#:&=-'3 )>

)0?0 !-,!&$%/#9 5'#:&=-'3 )<

)010 -$&'#%+-,#9 5'#:&=-'3 )1

)0@0 6%#%&:&,% -5 %"& $'-29&: );

)0;0 -2A&!%+B&6 -5 %"& 6%/.7 )C

)0C0 '&6&#'!" "7$-%"&6&6 )C

)0D0 #66/:$%+-,6 -5 %"& 6%/.7 )D

)0)>0 6!-$& #,. 9+:+%#%+-, -5 %"& 6%/.7 8)

)0))0 6+4,+5+!#,!& -5 %"& 6%/.7 <>

!"#$%&' 8* '&B+&= -5 '&9#%&. 9+%&'#%/'& 0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 <8

80)0 '&9#%+-,6"+$6 2&%=&&, 2'#,. &E/+%7F 2'#,. $'&5&'&,!&F #,. $/'!"#6& +,%&,% <8

8080 -%"&' 2'#,. &E/+%7 6%/.+&6 <1

80<0 :/'&:&,% :-.&96 ?8

80?0 '	 &6%#%& 6%/.+&6 ??

8010 6%/.+&6 -, 6&'B+!& +,./6%'+&6 ?D

80@0 6%/.+&6 -, 9/G/'7 2'#,.6 1)

80;0 67,%"&6+6 #,. !-::&,%#'7 -, '&B+&=&. 9+%&'#%/'& 1?

!"#$%&' <* :&%"-.-9-47 00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 1;

<0)0 '&6&#'!" .&6+4, 1;

<080 $-$/9#%+-, #,. 6#:$9& 6+H&6 1C

<0<0 6#:$9+,4 :&%"-. 1D

<0?0 6/'B&7 +,6%'/:&,% @>

<010 6%#%+6%+!#9 %'&#%:&,% -5 .#%# @8

!"#$%&' ?* $'&6&,%#%+-, #,. .#%# #,#976+6 00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 @1

?0)0 $'-5+9& -5 '&6$-,.&,%6 @1

?080 +,%&',#9 '&9+#2+9+%7 -5 :/'&6 @D

?0<0 '&9#%+-,6"+$ 2&%=&&, 2'#,. &E/+%7 #,. 2'#,. $'&5&'&,!& ;>

?0?0 '&9#%+-,6"+$ 2&%=&&, 2'#,. &E/+%7 #,. $/'!"#6& +,%&,% ;;

?0?0 '&9#%+-,6"+$ 2&%=&&, 2'#,. $'&5&'&,!& #,. $/'!"#6& +,%&,% C<

!"#$%&' 1* 6/::#'7F !-,!9/6+-,6 #,. '&!-::&,.#%+-,6 000000000000000000000 C1

10)0 6/::#'7 #,. !-,!9/6+-,6 C1

1080 '&!-::&,.#%+-,6 5-' 5/%/'& 6%/.+&6 D?

10<0 :#'3&%+,4 '&!-::&,.#%+-,6 D@

'&5&'&,!&6 0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 )>)

#$$&,.+G 000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 )>1

3

?),( *8 !'>&#,

%#29& )0 "9/'2 9+!&,6& +66/#,!&6 @

%#29& 80 5-'&!#6%&. '&6+.&,%+#9 6/$$97 /,%+9 7&#' 8>)? @

%#29& <0 $'-A&!%6 +,!9/.&. +, %"& 6%/.7 8@

%#29& ?0 6/::#'7 -5 '&9#%&. 9+%&'#%/'& 11

%#29& 10 +,.&$&,.&,% #,. .&$&,.&,% B#'+#29&6 1;

%#29& @0 '&E/+'&. '&6$-,.&,%6 $&' $'-A&!% 1D

%#29& ;0 9+,&#' '&4'&66+-, %&6% 6%#%+6%+!6 @<

%#29& C0 +,%&'$'&%#%+-, -5 $&#'6-, !-''&9#%+-, 6%#%+6%+! @<

%#29& D0 +,%&'$'&#%+-, -5 !'-,2#!"I6 #9$"# @?

%#29& )>0 +,%&',#9 !-,6+6%&,!7 -5 6%/.7 B#'+#29&6 ;>

%#29& ))0 9+,&#' '&4'&66+-, 6%#%+6%+!6* 2'#,. &E/+%7 #,. 2'#,. $'&5&'&,!& ;)

%#29& )80 9+,&#' '&4'&66+-, 6%#%+6%+!6* 2'#,. 9-7#9%7 #,. 2'#,. $'&5&'&,!& ;<

%#29& )<0 9+,&#' '&4'&66+-, 6%#%+6%+!6* 2'#,. E/#9+%7 #,. 2'#,. $'&5&'&,!& ;<

%#29& )?0 9+,&#' '&4'&66+-, 6%#%+6%+!6* 2'#,. #=#'&,&66 #,. 2'#,. $'&5&'&,!& ;?

%#29& )10 9+,&#' '&4'&66+-, 6%#%+6%+!6* 2'#,. #66-!+#%+-,6 #,. 2'#,. $'&5&'&,!& ;?

%#29& )@0 '&9#%+-,6"+$ 2&%=&&, 2'#,. &E/+%7 .+:&,%+-,6 #,. 2'#,. $'&5&'&,!& ;1

%#29& );0 9+,&#' '&4'&66+-, 6%#%+6%+!6* 2'#,. &E/+%7 #,. $/'!"#6& +,%&,% ;C

%#29& )C0 9+,&#' '&4'&66+-, 6%#%+6%+!6* 2'#,. 9-7#9%7 #,. $/'!"#6& +,%&,% ;D

%#29& )D0 9+,&#' '&4'&66+-, 6%#%+6%+!6* 2'#,. E/#9+%7 #,. $/'!"#6& +,%&,% ;D

%#29& 8>0 9+,&#' '&4'&66+-, 6%#%+6%+!6* 2'#,. #=#'&,&66 #,. $/'!"#6& +,%&,% C>

%#29& 8)0 9+,&#' '&4'&66+-, 6%#%+6%+!6* 2'#,. #66-!+#%+-,6 #,. $/'!"#6& +,%&,% C>

%#29& 880 '&9#%+-,6"+$ 2&%=&&, 2'#,. &E/+%7 .+:&,%+-,6 #,. $/'!"#6& +,%&,% C)

%#29& 8<0 9+,&#' '&4'&66+-, 6%#%+6%+!6* 2'#,. $'&5&'&,!& #,. $/'!"#6& +,%&,% C<

%#29& 8?0 %&6%+,4 -5 '&6&#'!" "7$-%"&6&6 CC

?),( *8 @)A40#,

5+4/'& )0 %"&-'&%+!#9 5'#:&=-'3* 2'#,. &E/+%7 #,. B#9/& 4&,&'#%+-, )8

5+4/'& 80 !-,!&$%/#9 5'#:&=-'3* #,%&!&.&,%6 #,. !-,6&E/&,!&6 -5 2'#,. &E/+%7 )?

5+4/'& <0 '&9#%+-,6"+$ 2&%=&&, 2'#,. &E/+%7F 2'#,. $'&5&'&,!&J )1

5+4/'& ?0 -$&'#%+-,#9 5'#:&=-'3 -5 %"& 6%/.7 )@

5+4/'& 10 #,%&!&.&,%6 -5 '&$/'!"#6& +,%&,% <;

5+4/'& @0 2'#,. $&'6-,#9+%7 5'#:&=-'3 ?>

5+4/'& ;0 6%'/!%/'& -5 2'#,. !-,!&$% ?@

5+4/'& C0 # :-.&9 -5 #,%+!+$#%&. '&4'&% #,. $-6%K$/'!"#6&J ?C

5+4/'& D0 !"#'#!%&'+6%+!6 -5 9/G/'7 2'#,.6 1<

5+4/'& )>0 $&'!&,%#4& -5 '&6$-,.&,%6 27 -!!/$#%+-, @1

5+4/'& ))0 $&'!&,%#4& -5 '&6$-,.&,%6 27 +,!-:& 4'-/$ @@

5+4/'& )80 $&'!&,%#4& -5 '&6$-,.&,%6 27 ,/:2&' -5 /,+%6 -=,&. @;

5+4/'& )<0 $&'!&,%#4& -5 '&6$-,.&,%6 27 $/'$-6& -5 -=,&'6"+$ @;

5+4/'& )?0 $&'!&,%#4& -5 '&6$-,.&,%6 27 +,%&'&6% +, 5/%/'& !-,.- $/'!"#6&6 @C

4

ABSTRACT

This study attempts to establish relationships between brand equity, brand

preference, and purchase intent in the increasingly competitive premium residential

condominium market in Metro Manila.

Brand equity was measured using scales derived from David Aakers customer-

based brand equity model, and then compared with corresponding survey results

regarding brand preference and purchase intent. The collected data was then subjected to

linear regression analysis to validate any possible correlations. The effects of each

dimension of brand equity as defined by Aaker (loyalty, awareness, associations, and

perceived quality) were also explored. To establish a cross-section of the entire industry,

data was collected in reference to five major real estate brands (Ayala Land Premier,

Shang Properties, Robinsons Luxuria, Century Properties, and Rockwell Land

Corporation).

Research scope was limited to premium residential condominium units (those

priced at about Php 120,000 170,000 per square meter). Furthermore, this study focuses

on a psychographic profile herein referred to as the value seeker.

Significant and positive correlations were found between brand equity, brand

preference, and purchase intent, as supported by a variety of studies that have reported

similar findings. Analysis of brand equity dimensions and suggested avenues for further

research conclude the paper.

5

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background of the Study

In contrast to the unfavorable outlook in other international real estate markets,

economic indicators related to the Philippine real estate market have shown highly

promising growth prospects.

For 2011, Colliers International reported an annual growth rate of 17% throughout

the real estate sub-sector, a figure that far exceeds the countrys GDP growth of 3.7%.

Similar growth rates were also reported for the first three quarters of 2012 (Colliers

Market Report, 2012).

Evidence also suggests that this growth is significantly buoyed by the high-rise

residential segment. HLURB license issuances for high-rise residential projects increased

by 31.7% from 2010 to 2011 (Table 1), a substantial figure considering the number of

projects involved as well as the capital-intensive nature of condominium development.

Based on forecasted residential supply figures, it is reasonable to expect the market to

maintain this growth trend for now, and until at least 2014 (Table 2).

The rapid growth in the local real estate sector is a potential opportunity for

significant shifts in market share, and for current leaders to further distance themselves

from the rest of the industry. For investors, this growth along with generally improving

6

economic fundamentals in the country makes real estate an increasingly promising value

proposition.

Table 1: HLURB License Issuances (adopted from Colliers Market Report, retrieved January 20,

2013 from http://www.colliers.com/en-GB/Philippines/Insights)

Table 2: Forecasted Residential Supply until year 2014 (adopted from Colliers Market Report,

retrieved January 20, 2013 from http://www.colliers.com/en-GB/Philippines/Insights)

7

Conducting a brand equity study may yield important insights regarding the

current state of the market and help predict customer purchase inclinations during this

critical growth period. This kind of study can also reveal important success factors that

real estate companies could focus on to improve overall brand performance.

1.2. Operational Definition of Terms

The following definitions will be used for purposes of this study:

Brand associations

The ability for consumers to identify characteristics of a developer as a premium

residential condominium brand. This also includes consumer association of its

projects specifically as premium brands.

Brand awareness

The ability to easily recall and recognize a developer as a premium residential

condominium brand. This involves both general awareness and top-of-mind

awareness.

8

Brand equity

The combined effect of all four dimensions of brand equity. This is assumed to be

the representation of a condominiums brand value to the consumer in the

premium residential condo market.

Brand loyalty

The general level of attachment and commitment a customer has towards a

particular brand in the premium residential condominium market.

Brand preference

The extent to which a customer favors a particular brand over any other as a

premium condominium brand.

Premium residential condominium units

Residential condominium units specifically designed for upscale (class AB)

customers, characterized by branded finishes and fixtures, spacious layouts (abour

50 square meters), and high-value locations inside business districts or key

lifestyle hubs. Correspondingly, these units command a high price, commonly

about Php120,000 P170,000 per square meter.

9

This study limits its focus on the following premium residential condominium

projects:

One Serendra (Ayala Land Premiere)

The Residences at Greenbelt (Ayala Land Premiere)

Sonata Private Residences (Robinsons Luxuria)

The Gramercy Residences (Century Properties)

One Rockwell (Rockwell Land Corporation)

Joya Lofts and Towers (Rockwell Land Corporation)

St. Francis Shangrila Place (Shang Properties)

Shang Grand Tower (Shang Properties)

Perceived quality

The customers assessment of the condominium products quality, both in terms

of the actual finished product and its expected rate of return on investment (for

investors).

Purchase intention

The expressed desire of a customer to actually buy a condominium unit, taking

into account his or her present situation and market factors.

10

1.3. Theoretical Framework

The importance of branding from a marketing standpoint is something that cannot

be overstated. Brand management allows a companys products to have unique identities

as well as distinct value associations in the minds of consumers. Without a recognizable

brand, companies would be unable to distinguish themselves among similar product

offerings. Branding is thus an indispensible part of creating customer loyalty, and it is for

this reason that brand management should be one of the primary marketing activities in

any commercial firm.

Moreover, branding is especially important in the condominium market due to its

role in alleviating possible purchase risks. A quality brand signals a certain level of

quality so that satisfied buyers can easily choose the product again (Kotler, 2012).

Buying from a well-established brand helps assure customers that they will receive a

product of a certain level of quality. And it is important to establish these expectations

because of the prevalence of the pre-selling model, wherein condominium units are sold

to buyers before the actual construction of the building. In these circumstances,

customers cannot see or personally inspect the quality of the unit being purchased. They

are shown only upgraded and dressed-up model units that are rarely an accurate

representation of the actual delivered product. This, along with the fact that real-estate

purchases are among the highest-value expenditures for any consumer, means that real

11

estate developers need to inspire a great deal of trust in consumers for them to close a

transaction.

Various methods to measure brand equity have been proposed. One approach is

conjoint analysis, which measures customer assessments of each relevant brand attribute

in order to arrive at an overall assessment of the entire brand. Such an approach is

infeasible in this study due to the sheer number of product attributes that have to be

evaluated in the purchase of condominium units

Other brand equity measurement models instead attempt to derive brand equity

from market information such as price premiums and/or market shares. Thus approach

could also be problematic at present due to the fast-changing conditions in the

condominium market. Both market share and general price levels are very likely to

change significantly within the next few months.

Brand equity can also be measured by breaking it down into several components

and measuring each component individually. Noted models that use this approach include

Young and Rubicams Brand Asset Valuator, David Aakers dimensions of Brand

Equity, and Millward Browns BrandZ model of brand strength. Aakers model has

particular relevance in this study due to the abundance of literature utilizing his model for

similar purposes. For this reason as well as those mentioned earlier, this research uses

survey scales based on the Aaker framework.

According to Aakers definition of brand equity, brand equity is composed of four

distinct dimensions, namely brand loyalty, perceived quality, brand awareness, and brand

12

associations. By measuring relative brand performance in terms of these entities, we can

theoretically assess how valuable of an asset a brand name is, and predict its ability to

add value for both the firm and its consumers (Figure 1). A fifth dimension, other

proprietary brand assets, can also be considered. These include patents, trademarks,

channel control and other such advantages specific to a brand. However, since the effect

on proprietary brand assets cannot be generalized, it is not considered in this research.

Figure 1: Theoretical Framework: Brand Equity and Value Generation (Aaker p. 9, 1996)

13

1.4. Conceptual Framework

To better understand how brand equity directly affects both preferences, and

purchase intentions, this study refers to a framework developed by Cobb-Walgren et al in

their research Brand Equity, Brand Preference, and Purchase Intent (1995). Their

framework effectively describes both sources and potential benefits of brand equity.

The framework states that information about a brands psychological and physical

features is made available to the consumer via direct marketing communications and

other channels, which influences his or her various impressions about a brand. These

perceptions in turn create brand equity and become a strong factor that influences both

preferences and purchase intentions, ultimately resulting in product choice. The

researchers summarized these interactions using the following diagram:

14

Figure 2: Conceptual Framework: Antecedents and Consequences of Brand Equity (adopted

from Brand Equity, Brand Preference and Purchase Intent p. 29 by Cobb-Walgren et al, 1995)

It is important to note the importance of measuring both brand preference and

purchase intent as predictors of general brand attractiveness. Purchase intent is

theoretically more likely to translate to actual sales, since this measure indicates actual

expressed desire to buy a product. However, purchase intent is also dependent on

extraneous situational factors such as availability, which may make brand preference a

more appropriate measure of brand strength in some cases.

15

1.5. Operational Framework

The operational framework used in this study is a derivation of that used in a

recent research work by Chen and Chang (Figure 3), essentially a streamlined

interpretation of the conceptual framework shown in Figure 2.

Figure 3: Relationship Between Brand Equity Brand Preference and Purchase Intent (adopted

from Brand Equity, Brand Preference, and Purchase Intent in Airlines p. 41 by Chen and Chang

(2008).

As depicted by the diagram, this framework also proposes that there are

relationships between brand equity, brand preference, and purchase intent. A similar

operational model is incorporated for this study, although the moderating effect of

switching costs need not be explored for our purposes.

16

The framework was also modified to reflect the research approach of expressing

brand equity as an average of all four of Aakers brand equity dimensions. The resulting

framework is as follows:

Figure 4: Operational Framework of the Study

Brand Preference is both an independent and dependent variable. This is because

the study explores both the relationship of brand equity on brand preference (where brand

preference is a dependent variable) as well as the effect of brand preference on purchase

intent (where brand preference is an independent variable).

17

1.6. Statement of the Problem

The general objectives of the study are summarized in the following problem

statement.

What are the relationships among brand equity dimensions, brand preference,

and purchase intent?

Following the operational framework, the problem can be broken down into three

main components:

1) What is the relationship between brand equity and brand preference?

2) What is the relationship between brand equity and purchase intent?

3) What is the relationship between brand preference and purchase intent?

18

1.7. Objectives of the Study

1.7.1. General Objective

To establish the relationships between brand equity, brand preference and

purchase intent.

1.7.2. Specific Objectives

1) To gain insight into key success factors in the market by looking at the

effects of the dimensions of brand equity

2) To increase understanding of how brand equity affects the premium

condominium market

3) To empirically confirm theoretical relationships between study

variables

1.8. Research Hypotheses

H1) Brand equity positively influences brand preference.

19

H2) Brand equity positively influences purchase intent.

H3) Brand preference positively influences purchase intent.

These relationships were observed in multiple studies, as identified in the review

of related literature. However, while there is a wide variety of literature pertaining to the

effect of brand equity on both brand preference and purchase intent, none of these studies

specifically involve the premium condominium market. As mentioned earlier, the

industry possesses some unique characteristics that may change the traditional role of

brand equity (pre-selling, high inherent risk). As such, the lack of material concerning

luxury condominiums represents a notable research gap that this study aims to address.

With the increasing prevalence of condominium living in Metro Manila, this information

could prove very valuable to industry marketers.

1.9. Assumptions of the Study

Survey respondents were limited to Metro Manila residents belonging to the

socioeconomic classes A and B, aged 40-60 years. This is the assumed target market of

premium condominium developments, mostly due to purchasing power. High-end

condominium units are characterized by spacious layouts, premium finishes, as well as

excellent ancillary services in most cases. These features substantially increase

20

development costs to the point where the corresponding sale prices are accessible only to

Class AB buyers. For this same reason, the study was limited to Metro Manila, where

relative income levels are highest, a situation that is likely to remain for the foreseeable

future. The 40-60 age group was targeted in particular since they are the most frequent

buyers of premium condominiums, as supported by an actual sales report from one of the

most reputable real estate companies in the country (name of company withheld as per

request).

All study data was derived almost entirely from survey questionnaires, since it is

mostly concerned with general consumer perceptions and evaluations. Interviews with

real estate developers and personal experience provided additional depth in the analysis.

A linear correlation is assumed among the study variables. This kind of

relationship can be reasonably expected given the nature of the relationships of each

entity. As such, the simplifying assumption was made to limit statistical treatment.

Moreover, pre-test data showed high degrees of significance and correlation strength for

linear regression, lending credence to this assumption. It should also be noted that since

brand preference and purchase intent are expressed as averages of multi-item scales, they

cannot be characterized as fixed-interval variables. Therefore, linear regression is more

appropriately applied as opposed to logistic regression, a technique that is appropriately

used when dependent variables are discrete or categorical.

Finally, in arriving at a total brand equity measure, it is assumed that each

dimension of Aakers model has equal relevance. Other studies have proposed

21

methodologies for deriving the relative importance of each dimension, however these

require specialized software (EQS, LISREL, AMOS for SPSS). Instead, brand equity was

calculated as a simple average of all four dimensions, similar to the assumption made by

Cobb-Walgren et al (1995). In practice this does not prove to be a significant hindrance to

the study, since all four dimensions are expected to have the same directional relationship

with both brand preference and purchase intent. To be cautious however, this limitation

was taken into account during data analysis.

1.10. Scope and Limitation of the Study

In addition to targeting only a specific demographic profile, the study also limited

its focus on a specific psychographic profile, hereafter referred to as the value seeker.

Unlike other market segments that may prioritize prestige, exclusivity, or other non-

tangible benefits, value seekers only purchase what they believe to be the best package of

practical benefits at a certain price. For example, the value seeker may consider a project

such as Trump Tower Manila to be overpriced since the Trump name may be perceived

to artificially inflate sales prices while offering no additional benefits aside from prestige.

As suggested by their behavior, value seekers are pragmatic and highly rational. Those

who purchase condominiums purely as investment vehicles are also considered value

seekers, since they are concerned solely with financial return.

22

Based on both pre-test data and anecdotal evidence, the value seeker seems to be

the most common psychographic profile in the target demographic. This is to be expected

since the market is comprised mostly of highly successful executives and entrepreneurs,

who tend to be very discerning, demanding, and investment-savvy.

To approximate the behavior of the entire industry, five brands were selected

which are assumed to represent a reasonable cross-section of the premium condominium

market. Brands with varying profiles were intentionally chosen to ensure that relationship

trends occur industry-wide, rather than as a result of brand-specific behavior. The chosen

brands are all well known yet have significantly different strengths and weaknesses, thus

making them appropriate for study purposes.

Ayala Land Premiere is known is one of the oldest and most reliable brands in the

industry. Given its extensive track record for producing quality high-end projects, it has

earned its reputation as a trusted, quality developer. Ayala Land also is known as the

market leader in high-end commercial mall development, a likely source of positive

brand associations.

23

Century Properties is relatively new as a major player in the premium

condominium industry. Of late, it has succeeding in creating mainstream awareness of its

projects through partnerships with highly influential international names such as Versace

Home, Trump Properties, and endorser Paris Hilton. Unlike other developers though, its

portfolio of completed high-end projects is very limited, which could affect general

perceptions of product quality.

Shang Properties is the local subsidiary of the Kuok Limited, a renowned

premium developer with projects in Malaysia, Singapore, Hong Kong, Thailand, the

Philippines, China, Canada, and Australia. The company has the distinction of being the

only major player with an internationally established brand name. The Shangrila name is

also known for its highly successful upscale mall and hotels, likely improving its brand

association and image.

24

Robinsons Luxuria is the premium condominium brand of Robinsons Lard

Corporation, one of the oldest and most well known brands in Philippine real estate.

However, the brand is a fairly recent entry into the premium segment and is likely better

known as a mid-end developer. Additionally, Robinsons Land Corporation also operates

one of the countrys largest and most popular mid-end mall chains, which could also have

implications regarding its acceptance as a premium brand.

Rockwell Land Corporation is another very prominent name in the premium

condominium industry. The brand enjoys strong mindshare and image perceptions due to

its exceptionally designed pocket community in Makati City, which include properties

25

that currently command some of the highest rental rates in Metro Manila. However, the

companys premium projects are isolated in this one area, so its portfolio is rather limited.

For better cross-brand comparability, this study focused only on projects with

relatively similar characteristics. Projects were chosen to be as similar as possible with

regard to price per square meter and relative unit sizes (measured using 1BR units, since

this is the most common unit type). Completed projects were chosen instead of pre-

selling projects, as those are the ones can be properly evaluated in terms of quality.

Moreover, older projects (more than 5 years old) were not included to avoid overly

distorting price comparisons.

The selected projects are all expected to have some appeal for the target market of

value seekers. Serendra and The Residences at Greenbelt are both high-profile projects in

two of the most sought-after locations in Metro Manila, insulating their value from a

possible real estate market crash. Sonata Private Residences is another appealing value

purchase, as it offers a reasonable price given its location, which is possibly the best spot

in Ortigas to construct a residential condominium. Similarly, The Gramercy likewise

offers good value in an excellent location, and its value will likely appreciate further due

to its proximity to the future Trump Tower Manila, and the Versace-designed Milano

Residences. The entire Rockwell Center is an exceptionally designed pocket community,

making it appealing for both residents and investors alike. Finally, the Shangrila projects,

26

while they definitely command price premiums, are both sound investments as well due

to strong sustained demand and international brand presence.

The following table summarizes each chosen projects main characteristics:

Table 3: Projects Included in the Study

Project Name Brand Price per

sqm*

Ave 1BR unit

size*

Number of

Units*

Location

One Serendra

Ayala Land

Premiere

~140,000 ~60 sqm 744

Bonifacio

Global City

The Residences

at Greenbelt

Ayala Land

Premiere

~160,000 ~65 sqm 1300 Makati

Sonata Private

Residences

Robinsons

Luxuria

~130,000 ~45 sqm 758 Ortigas

The Gramercy

Residences

Century

Properties

~140,000 ~45 sqm 950 Makati

One Rockwell

Rockwell Land

Corporation

~150,000 ~60 sqm 900 Makati

Joya Lofts and

Towers

Rockwell Land

Corporation

~140,000 ~50 sqm 400 Makati

St. Francis

Shangrila Place

Shang

Properties

~140,000 ~60 sqm 700 Ortigas

Shang Grand

Tower

Shang

Properties

~170,000 ~60 sqm 250 Makati

* Approximated based on online advertisements and informal inquiries from sellers

Respondents were similarly limited only to those who actually own one or more

units from these selected projects, since their prior experience with the brand enables

them to make informed judgments about it. Broker networks and/or company sales agents

were tapped in order to contact existing unit owners and request their participation in the

survey.

27

Survey respondents were asked to rate their perceptions of each brand with

respect to consumer attitude perception scales measuring brand equity, preference, and

purchase intent.

The scale used for measuring brand equity was adopted from a study conducted

by Yoo/Donthu (2001), modified to specifically mention characteristics of the premium

condominium market as well as to eliminate the redundancy of some of the original scale

items. Given the objectives of the study, the aforementioned researchers proposed 10-

item model, which measures each dimension separately, proved to more appropriate for

its purposes compared to their proposed 4-item model that attempts to measure brand

equity as a whole. While Yoo/Donthu recommend combining brand awareness and brand

associations into a single construct, these dimensions were analyzed separately in this

study in order to isolate the unique effects of each dimension. Also, due to limitations

discussed earlier, total brand equity measures were derived by getting the simple average

of all four dimensions.

A potential source of confusion in answering the survey was that some of the

brands involved in the study have sister brands targeting other segments. This was

addressed by further modifying the scales to reflect the focus on only the premium

condominium market. The revised questions are as follows:

28

*X refers to specific real estate brands

Brand Loyalty

1) I consider myself loyal to X in the premium condominium market.

2) X would be my first choice for premium condominium units.

3) I would not buy other brands of premium condominiums if X were available.

Perceived Quality

1) The likelihood of quality of X is extremely high for their premium

condominiums.

2) The likelihood that the premium condominium units of X would greatly

appreciate in value is very high.

Brand Awareness

1) I can recognize X among other brands in the premium condominium segment.

2) X is the first brand that comes to mind when I think of premium

condominiums.

Brand Associations

1) Some characteristics of X as a premium condominium brand come to mind

quickly.

29

2) I can quickly recall several projects developed by X.

3) I have difficulty in imagining X in my mind as a premium condominium

developer.

Measures of brand preference and purchase intent were taken from a study

conducted by Chen/Chang (2008). The following four-item scale was used to evaluate

brand perception, again modified to specifically indicate the premium condominium

market and eliminate redundancy:

Brand Preference

1) I feel that X is an appealing brand for premium condominiums.

2) For me, X is the best premium condominium brand in the market.

3) If I were to purchase a premium condominium unit, I would prefer X if

everything was equal.

A straightforward two-item scale was also appropriated and modified from

Chen/Changs study (2008) to measure purchase intent:

Purchase Intent

1) I am willing to recommend others to buy premium condominium units from

X.

30

2) If I eventually find myself in the market for premium condominium units, I

would be willing to purchase from X.

1.11. Significance of the Study

Value to the Industry

The value of this study is probably greatest for the local condominium industry.

As of this writing, there does not seem to be any well-known brand equity studies that

focus on the high-rise residential market, and there are some unique characteristics in the

condominium industry that may influence how brand equity relates to both brand

preference and purchase intent. First, condominium purchases occur very infrequently in

a customers lifetime, so each customer tends to have a very narrow range of first-hand

experiences regarding each brands products. This potentially affects the usual role of

brand loyalty, which normally involves multiple repeat purchases from the same brand.

As mentioned earlier, the prevalence of the condominium pre-selling model could

increase customer reliance on brand equity, perhaps across all four of Aakers

dimensions. Furthermore, condominium units are extremely high-involvement purchases,

requiring extensive thought and evaluation prior to the actual purchase decision.

Customer perceptions may therefore play a much greater role than they would for

impulse purchases or other low-involvement items.

31

Knowing the importance of each dimension of brand equity will enable real estate

developers and salespeople to adjust their marketing activities accordingly. Competitive

advantages may be generated with proper focus towards the most important dimensions

of brand equity.

Value to the Academe and Future Researchers

This study can help address the dearth of studies specifically related to the rapidly

growing condominium segment. Condominium living is becoming an increasingly

common occurrence in Metro Manila, and it thus becomes increasingly more important to

understand market characteristics as best as possible.

In general, this study could also further reinforce the all-important relationships

between the three main study variables, as well as the scales used to measure them. The

importance of brand equity is easily appreciated when seen as a powerful influencer of

specific attitudes and behavior towards a brand. Thus, confirmation of the proposed

hypotheses would further support the importance of brand equity management.

Finally, this study also contributes to the universitys library of research works,

hopefully providing both students and faculty with possible areas of further research

involving these important topics. Methodologies and statistical methods employed in this

study could also be appropriated for related studies.

32

CHAPTER 2

REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

2.1. Relationships Between Brand Equity, Brand Preference, and Purchase Intent

A wide variety of sources are available supporting the proposed relationships.

One of the most influential is the work of Cobb-Walgren et al (1995) entitled Brand

Equity, Brand Preference, and Purchase Intent. Unlike what is proposed in this research,

the study conducted by Cobb-Walgren et al explored two separate industries (value hotels

chains and bathroom cleansers) and found that brand equity has a significant effect on

both. By doing so, the researchers were able to establish that strong brand equities

translated to improved market performance in both goods and service industries. Another

key difference in methodology is the use of conjoint analysis in establishing the

relationship between brand equity and brand preference. This can be effective in studying

hotel chains or bathroom cleansers, industries wherein a single brands products share

very similar characteristics. However, an attribute-based evaluation method such as

conjoint analysis is not necessarily the most suitable method for studying condominium

brands because one projects attributes can differ substantially from another project of the

same brand.

33

Cobb-Walgren et al utilized a unique method of selecting brands to research.

Using consumer reports, two brands were chosen from each industry that had nearly

identical scores in terms of objectively measured attributes, but varied dramatically in

terms of advertising support. In both industries studied, the brand with greater advertising

support scored much higher brand equity ratings, as well as far better scores in both brand

preference and purchase intent.

It is important to note that Cobb-Walgren et al chose to calculate brand equity as a

simple average of all four dimensions, rather than using a weighted average as

recommended by Aaker. The researchers speculated that any proposed weighting scheme

would vary from brand to brand, and lacking an established method for deriving these

weights, decided to apply uniform weights instead. It is pointed out however that

regardless of weighting, the end conclusions would remain unchanged since the better-

rated brands scored higher in each individual dimension of brand equity.

Other studies introduced moderating effects in the framework. Moderating effects

are those that have an influencing role in the relationships of the variables being studied.

As mentioned earlier, Chen/Chang (2008) discovered that switching costs had a

moderating role in the effect of brand equity on both preference and purchase intent in

the Taiwanese airline industry.

Unfortunately, no information was provided regarding the actual scales used for

measurement of brand equity, other than stating that the instrument used included all four

34

of Aakers dimensions. Data was collected from a convenience sample and is therefore

not completely random, but given the nature of the study, this was not expected to

significantly distort the end results.

Statistical analysis was performed by using structural equation modeling and

evaluating the corresponding statistical metrics (goodness-of-fit index, comparative-fit

index, and root-mean-square error approximation). All relationships pertaining to the

effect of brand equity on both purchase intent and brand preference were shown to be

significant by all measures.

A similar study conducted by Moradi/Zarei (2011) found that a cellphones

country of origin image (the image of the country where the phone was manufactured)

had a moderating role on the effect of brand equity on preference and purchase intent in

the Iranian market.

The study closely followed the methodology proposed by Chen/Chang (2008),

slightly modified to reflect the difference in market focus as well as the moderating effect

being explored. Brand equity measures were adopted from a combination of studies,

although once again the specific items that were adopted were not identified. Similar to

the Chen/Chang study though, all four dimensions of Aakers brand equity framework

were included.

The researchers used LISREL 8.54 for structural equation modeling to test its

hypotheses, and the expected results were all supported by the collected survey data. In

35

line with previously cited studies, brand equity measures were shown to be significantly

and positively related to both brand preference and brand equity.

Studies across several product categories and cultural settings have concluded that

both brand preference and purchase intent increase as brand equity increases. Similarly,

purchase intent was also shown to increase as brand preference increases. These studies

therefore form the bases for the research hypotheses presented in pages 18-19.

2.2. Other Brand Equity Studies

Another brand equity study explored the effects of both brand attitudes and brand

image as expected antecedents of brand equity. This research work, The Antecedents

and Consequences of Brand Equity in Service Markets by Chang et al (2008), also

statistically established the positive effect of brand equity on both brand preference and

purchase intent.

The researchers included three service categories in their study, namely mobile

telecommunications, Internet (ADSL) services, and bank credit cards. These industries

were chosen because they represent certain important characteristics of service industries,

such as intangibility and high relevance of employee-customer interactions. Six brands

per category were used in the study, presumably to create a satisfactory cross-section of

each.

36

Chang et al deviated significantly from the previously cited material in terms of

statistical treatment. Instead of using conjoint analysis, they used the multidimensional

brand equity scale developed by Yoo/Donthu (2001) as a means of measuring brand

equity. The validating study of Washburn/Plank (2002) was cited as support. Like

Yoo/Donthu, the researchers found than the scale items used to measure

awareness/associations were essentially inseparable, and are thus better treated as a single

entity. Subsequent testing of internal reliability using Cronbachs alpha supported this

setup of survey parameters. Validity of correlations was tested using LISREL software

(version 8.52, 2002), and subjecting each resulting path coefficient to t-tests.

These findings are of particular interest because of the concentration on service

industries. Citing previous research by Zeithaml et al (1985) and Laroche et al (2003,

2004), the researchers pointed out how intangibility in service industries makes it more

difficult for customers to evaluate product attributes, thus increasing customer reliance on

brand reputation in making purchase decisions. Service industries also tend to have

higher switching costs due to a greater need for time-consuming information search prior

to purchase. As such, satisfied customers can be theoretically easier to retain.

A more detailed approach in assessing relationships between the dimensions of

brand equity and its effect on both brand preference and purchase intention was that of

Hellier et al, in their study Customer Repurchase Intention: A general structural

equation model (2003). While this research does not specifically refer to brand equity,

37

both perceived quality and customer loyalty are identified as antecedents of brand

preference and repurchase intent.

The study made use of the following framework in an attempt to gain a more

precise understanding about what drives brand preference:

Figure 5: Antecedents of Repurchase Intent (adopted from Customer Repurchase

Intention: A General Structural Equation Model by Hellier et al p. 1765, 2003)

38

As seen in the diagram, the study included many other factors that influence

preference and intent. Despite this significant shift in focus, the researchers hypotheses

remained consistent with earlier findings: components of brand equity were expected to

positively influence both preference and purchase intention, whether directly or

indirectly.

Another big difference between the study of Hellier et al compared to those

previously cited is that it did not account for either brand awareness or brand

associations. Also, it focused on repurchase intentions of customers who have had

significant exposure and experience with the brand. Since condominium purchases are

not regular purchases, results potentially may vary from those presented in the study.

Statistical treatment also deviated from previously cited works; the researchers used EQS

software for structural equation modeling.

In another study, Stahl et al (2012) attempted to establish the importance of brand

equity by examining its effect on hard measures such as customer acquisition, retention,

and profit margin (the aggregate effect of these is referred to as CLV or customer lifetime

value). Unlike the literature mentioned earlier, this research utilized Young and

Rubicams Brand Asset Valuator, a model that describes brand equity in terms of four

entirely different components (differentiation, relevance, knowledge, and esteem).

It was suggested that relevance, knowledge, and esteem all significantly and

positively affect CLV for various reasons. However researchers proposed that

39

differentiation actually has an adverse effect on both customer acquisition and retention

the more unique a product is, the more unique its target market gets. On the other hand,

this kind of focus strategy would generally lead to an increase in margins, as target

customers would theoretically see more value in the differentiated product. Regression

analysis was used to test the various hypotheses, and statistical results were all in line

with expected findings.

The study focused only on the US automotive industry, which is very similar to

the condominium industry considering that both are very high-involvement products with

a multitude of attributes that need to be evaluated in order to make an informed decision.

As such, there is a strong likelihood that this study will yield results in line with those

presented by Stahl et al, assuming that the Brand Asset Valuator and the Aaker brand

equity model do indeed measure the same underlying construct.

Focusing on one of the broader dimensions of brand equity, OCass and Lim

(2001) created their study The Influence of Brand Associations on Brand Preference and

Purchase Intention: An Asian Perspective on Brand Associations. The researchers

focused particularly on non-product-related associations as defined by Keller in his book

Strategic Brand Management (1998). These are categorized into four: price associations,

user and usage imagery, brand personality, and feelings and experiences.

For Keller, price associations can be considered non-product-related attributes

insofar as they do not necessarily contribute to product quality or function. Price levels

40

merely provide signals to consumers as to what kind of quality can be expected out of the

product. User and usage imagery refer to generalized images of brand users and usage

scenarios, usually formed through exposure to advertising communications and past

experiences with actual brand users. Feelings and experiences are simply the actual

emotions and knowledge a customer has in relation to a particular brand. Finally, brand

personality involves ascribing human-like qualities to a brand in line with pervading

perceptions or imagery attached to it. The following framework was adopted from Aaker

(Dimensions of Brand Personality, 1997) to measure brand personality:

Figure 6: Brand Personality Framework (adopted from Dimensions of Brand Personality by D.

Aaker, 1997)

OCass and Lim suggested that, even without referring to tangible product

attributes, branding activities can still provide a source of sustainable competitive

advantage for a firm. To support this assertion, Singaporean students were surveyed and

asked to evaluate fashion apparel brands in terms of the aforementioned non-product-

41

related attributes, brand preference, and purchase intention. Using regression analysis, it

was discovered that the brands with positive associations and imagery congruent to the

users self-image turned out to be the users preferred brands. Purchase intent is similarly

correlated to brand associations as well.

In contrast to most of the studies cited herein, Mizik and Jacobson (2008)

explored the value of brand equity from the firms perspective. In particular, the authors

studied the correlation between brand assets (as measured by Young and Rubicams

Brand Asset Valuator), and corporate financial metrics such as sales growth,

unanticipated return on assets, and stock returns.

`Their research used information obtained directly from the Young and Rubicam

database, as well as audited financial data spanning 11 years. It included several well-

known brands across various unrelated industries, namely Starbucks, IBM, AOL, Yahoo,

Martha Stewart, and Wal-Mart.

The end results, analyzed using Pearson coefficients, were mixed. While some of

the results showed the expected positive correlations, Differentiation for instance was

shown to be statistically unrelated to any financial measure. Furthermore, the data

indicated that neither knowledge nor relevance significantly affected unanticipated return

on assets.

The researchers noted that there are several mitigating variables that may have

affected the analysis (such as delay of market information, the nature of the measures in

42

general, etc.). Macroeconomic and operational factors were also likely to affect the

results. Lacking a better framework in place to isolate the effect of brand assets on

company financial performance, direct correlation analysis may prove inconclusive.

2.3. Measurement Models

Other researchers proposed different measures of brand equity and assessed their

validity. The most important in the context of this study is Yoo/Donthus study entitled

Developing and Validating a Multidimensional Consumer-Based Brand Equity Scale

(2001), since the brand equity measures used herein were appropriated from this research.

Yoo/Donthu attempted to establish a single brand equity scale that could be

standardized across cultures and product categories, based on the Aakers conceptual

model of brand equity. The researchers wanted the measure to be valid, reliable, and

generalizable. To test the developed scales under these criteria, statistical results of brand

equity measures were compared using data from three distinct product groups (athletic

shoes, film, color television sets) and three different cultural groups (Americans, Korean

Americans, and Koreans).

Using LISREL modeling and other correlation measures, the researchers found

that there was no significant variance attributable to cultural or product category

influences when the proposed scales were used. This indicates that they can be

appropriately applied to any cultural or product group. However Yoo/Donthu also

43

discovered that the relative importance of each dimension of brand equity would differ

depending on context. And since the four dimensions affect brand equity to varying

degrees, a single brand equity score could not be derived by simply adding up the scores

of each individual dimension. Yoo/Donthu instead proposed weighting each dimension

according to their respective path coefficients as derived from LISREL.

Additionally, the collected results did not reflect brand awareness and brand

associations as two distinct dimensions. Variance comparison tests showed that the two

dimensions showed are essentially inseparable from a statistical standpoint. As such,

researchers combined the two dimensions into a single measure.

Primarily due its proven validity across product categories and different cultures,

this researcher believes that this is the most appropriate reference scale that can be

applied in this study.

Another approach to brand equity measurement was suggested by Park/Srinivasan

in their study A Survey-Based Method for Measuring and Understanding Brand Equity

and Its Extendibility (1994). The aim of their study was to isolate the effects of the

brand name itself in adding value to a product. In this context, brand equity was defined

as the difference between an individual consumer's overall brand preference and his or

her multiattributed preference based on objectively measured attribute levels (Park &

Srinivasan, 1994). For instance, if there are two brands with exactly the same objectively

measured attributes but with significantly different levels of market acceptance, the

44

better-accepted brand is considered the one with better brand equity.

Park/Srinivasan came up with a model that broke down brand equity into two

parts: the effect of brand equity in influencing customer perceptions (the difference

between subjective evaluation of product attributes versus actual or objective measures),

and the value of non-attribute-based components of brand equity, such as image. Various

statistical measures supported this models validity and predictive power in both the US

toothpaste and mouthwash categories.

Despite the potential diagnostic value of such an approach, it was not adopted in

this study due to the aforementioned difficulties in applying multi-attribute models to the

condominium industry, wherein products are composed of dozens of relevant attributes

that vary significantly even within the same brand.

2.4. Real Estate Studies

Branding studies specific to the real estate industry proved more difficult to find.

Gulas et al conducted one of the more significant research works, Brand and Message

Recall: The Effects of Situational Involvement and Brand Symbols in the Marketing of

Real Estate Services (2009). Gulas et al proposed that brand recall in the real estate

industry is positively influenced by both a customers intention to purchase real estate in

the near future (situational involvement), as well as the use of tangible imagery in

marketing communications.

45

Using a combination of descriptive statistics and chi-squared testing, researchers

found a significant relationship between brand recall and use of tangible imagery.

However, it was also discovered that situational involvement had no meaningful effect on

brand recall of the top five US real estate brands, despite it having a significant impact on

brand recall of the less-popular brands. Researchers explained this by pointing out that

larger brands generally have more extensive marketing communication campaigns, which

helps them attract attention even from those who are not immediately considering a real

estate purchase. These findings suggest that in real estate branding research, the use of a

random sample, as opposed to a sample of consisting of buyers actively searching for a

condominium unit, can be rightfully justified.

A Finnish study proposed a benchmarking tool for analysis of real estate brand

value. It focused on brand value specifically for occupiers of commercial properties. This

research, entitled Brand in the Real Estate Business Concept, Idea, Value, considers

four main sources of real estate value: location, image, performance, and services (Figure

7).

46

Figure 7: Structure of Brand Concept (taken from Brand in the Real Estate Business

Concept, Idea, Value by Viitanen, 2004)

Location is of course probably the single most important driver of real estate

value. The researcher considers accessibility, parking, infrastructure, and surroundings to

be the key determinants of a good location.

Performance is a measure of both building safety and functionality. A commercial

leasing operation that performs well has to comply with all applicable safety regulations,

and have equipment in good working order. Additionally, it should also be flexible and

adaptable to possible changes in tenant space requirements.

47

Services refer to additional value-added benefits provided by building

administrators. This includes high-quality telecommunication amenities and a pleasant

environment for its tenants.

Finally, image involves positive images and associations for the building. This is

important in the industry because the image of the occupier is invariably linked to the

image of the premises.

By using a specialized benchmarking tool, Viitanen confirmed that developing

real estate brands could lead to meaningful differentiation and positive value for the

company. He pointed out that effective commercial concepts can potentially result in

both higher rental rates and occupancy compared to similarly located projects.

Another important insight provided by the study is that each commercial building

forms a part of the brand character and that a building as a product may form an

individual brand. In other words, because buildings have distinct characteristics and

value associations, each building can almost be treated as an entirely distinct brand.

While presenting a completely different approach, the study does provide

additional evidence regarding the positive value of brand in a real estate context.

Another interesting study that has implications on real estate branding is

Perceived Risk, Anticipated Regret and Post-Purchase Experience in the Real Estate

Market: The Case of China by Chen et al (2011).

48

The basic premise of this study is that since home purchases are inherently risky,

there is a large degree of anticipated regret that actually reduces post-purchase

satisfaction.

Perceived risk is caused by importance, irreversibility, and difficulty in making

housing purchases. This risk exerts a lot of pressure on buyers, making it a significant

source of anticipated regret. And that feeling becomes so prevalent on consumers minds

that it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, causing them to believe perceptions that are not

necessarily based on reality (a phenomenon Chen et al refer to as CFT or counterfactual

thinking). With these negative perceptions then come feelings of actual or experienced

regret, ultimately resulting in dissatisfaction. This conceptual model is summarized in

Figure 8.

Figure 8: A Model of Anticipated Regret and Post-purchase Experience in Home

Purchase (from Perceived Risk, Anticipated Regret, and Post-Purchase Experience in the

Real Estate Market: The Case of China by Chen et al, 2011)

49

Structural Equation Modeling, together with the associated goodness-of-fit

indices, confirmed these relationships in the Chinese market. Since the underlying

concepts also apply to condominium purchases, there is also good reason to believe the

same holds true in that industry as well.

In theory, the implication here is that since pre-purchase perceived risks play a

significant role in reducing post-purchase satisfaction, effective brand marketing can

increase satisfaction because of its ability to alleviate purchase risks. By buying from a

trusted developer of known quality, the inherent risks in purchasing a house can be

somewhat mitigated, thus lessening the possible dissatisfaction.

2.5. Studies on Service Industries

Other studies on the characteristics of service industries also provide useful

insights regarding the proposed research. Berry (2000) wrote an insightful article entitled

Cultivating Service Brand Equity. This piece discussed several ways in which

successful branding initiatives aids in marketing.

First and foremost, branding increases customer trust of invisible products while

helping them to better understand and visualize what they are buying (Berry, 2000). As

mentioned earlier, this kind of intangibility is apparent in the condominium market due to

the prevalence of pre-selling. Developers that do a better job of inspiring trust in their

consumers will also do a better job in mitigating uncertainty concerns.

50

Branding also enables a company to effectively communicate their reason-for-

being, strengthen emotional connections to customers, and provide clear directions for

service employees on how to conduct themselves. All these things contribute positively

towards delivering a differentiated and meaningful value to customers and could be a

definite anchor for sustained competitive advantage.

Berrys service-branding model also provides additional evidence regarding the

importance of brand awareness. This model defined brand equity as the synergy between

brand awareness and brand meaning.

Similar findings were concluded by Laroche et al in Exploring How Intangibility

Affects Perceived Risk (2004). This research showed that the characteristics of service

industries (intangibility and generality) have an influence on the five dimensions of

perceived risk (financial risk, time risk, performance risk, social risk, psychological risk).

Both mental intangibility and physical intangibility were confirmed to have an

effect on dimensions of perceived risk, with mental intangibility having a stronger effect

than physical intangibility. This means that if a consumer is unable to mentally

understand and/or physically assess product benefits, he or she feels more associated risk

with the purchase. More importantly, Laroche et al discovered that branding helps to

diminish the usual role of intangibility on perceived risk.

Theoretically, this means that the specific brand messages communicated to

costumers allows them to have a better idea of what exactly it is they can expect out of a

51

service product and what benefits the product can bring. This gives consumers some

added security that partially offsets the concerns of buying a product that cannot be

physically interacted with and/or mentally visualized.

2.6. Studies on Luxury Brands

Other important insights were also obtained by referencing studies on luxury

brands. One example is Developing Experience-Based Luxury Brand Equity in the

Luxury Resorts Hotel Industry by Hung et al (2012).

While this study partially employs the Aaker model in its measurement of brand

equity, Hung et al also suggest that brand equity in the luxury market is more strongly

influenced by what they call extended implicit value (EIV). EIV includes elements

such as perceived luxury, experience value, and product uniqueness. The premise of the

study is that the appeal of luxury hotels is defined largely by image and expectations, as

opposed to other markets wherein Aakers original brand equity dimensions (referred to

as FEV or fundamental explicit value) would be more highly valued.

Actual results however, were mixed. Taiwanese consumers tended to favor FEV

while customers in Macau prioritized EIV. Hung et al speculate that this dichotomy in

consumer preferences is mostly due to the differences in the general market; Taiwanese

customers tend to be mostly locals while Macau customers are mostly international

tourists.

52

It should therefore be noted that results obtained from this study are expected to

hold true only in the context of the specific markets that were researched. Also, while this

study presumes that EIV is not a key determinant of brand equity for the target market of

value seekers, future studies may have to consider the effect of EIV in other brand equity

studies involving high-value products.

Another reference regarding branding for luxury products is Kellers Managing

the Growth Tradeoff: Challenges and Opportunities in Luxury Branding (2009). Keller

proposes 10 basic characteristics that define luxury brands. These are enumerated in

Figure 9.

At first glance, Kellers characteristics seem to imply that luxury branding places

a more prominent role on brand associations compared to the other dimensions. Items 1,

2, 4, 5, 7, and 8 are all mostly related to brands associations, while the other dimensions

are not given much mention, if at all. However upon further analysis, this may not

necessarily be the case. For instance, creation of brand associations is contingent upon

creating a certain level of brand awareness. Associations and brand image could also

conceivably be antecedents of brand loyalty. Because of these intrinsic relationships, the

importance of the other brand equity dimensions may not be dismissed. It is however,

possible that brand associations may have a relatively more important role in brand

equity for high-value products as opposed to lower-value products, and this will be taken

into account during data analysis.

53

Figure 9: Characteristics of Luxury Brands (adopted from Managing the Growth

Tradeoff: Challenges and Opportunities in Luxury Branding by Keller, 2009)

54

2.7. Synthesis and Commentary on Reviewed Literature

In summary, the references and studies cited are almost unanimously consistent

with the idea that brand preference and purchase intent will increase as brand equity

increases. This relationship is in line with every conceptual framework discussed, and is

concretely supported by data gathered across many different product types, service

categories, and even cultural settings. Similarly, many different sources have agreed that

each dimension of brand equity contributes to this relationship to some degree. This

suggests a strong likelihood that the same correlations will hold true even in the relatively

unique condominium industry.

Furthermore, research methodologies have been refined over a period of many

years and are consequently well developed. Resulting data has been subjected to multiple

testing using a variety of statistical tools, and have been found to be both valid and

appropriate for the study objectives. For these reasons, the methodology proposed herein

borrows heavily from these past works, with only slight deviations to reflect the

difference in market focus and to generally go into greater detail about the findings.

Table 4 summarizes all related literature cited in this study:

55

Table 4: Summary of Related Literature

Subject Author (Year) Title Page

Framework

Studies

Cobb-Walgren

et al (1995)

Brand Equity, Brand Preference and

Purchase Intent

32

Chen & Chang

(2008)

Airline Brand Equity, Brand

Preference and Purchase Intentions:

The Moderating Effects of

Switching Costs

33

Moradi & Zarei

(2011)

The Impact of Brand Equity on

Purchase Intention and Brand

Preference The Moderating

Effects of Country of Origin Image

34

Other Brand

Equity Studies

Chang et al

(2008)

The Antecedents and Consequences

of Brand Equity in Service Markets

35

Hellier et al

(2003)

Customer Repurchase Intention: A

General Structural Equation Model

36

Stahl et al

(2012)

The Impact of Brand Equity on

Customer Acquisition, Retention

and Profit Margin

38

OCass & Lim

(2001)

The Influence of Brand

Associations on Brand Preference

and Purchase Intent: An Asian

Perspective on Brand Associations

39

Mizik &

Jacobson

(2008)

The Financial Value Impact of

Perceptual Brand Attributes

41

Measurement

Models

Yoo & Donthu

(2001)

Developing and Validating a

Multidimensional Customer-Based

Brand Equity Scale

42

Park &

Srinivasan

(1994)

A Survey-Based Method for

Measuring and Understanding

Brand Equity and its Extendibility

43

56

Table 4 (continued): Summary of Related Literature

Subject Author (Year) Title Page

Real Estate

Studies

Gulas et al

(2009)

Brand and Message Recall: The

Effects of Situational Involvement

and Brand Symbols in the

Marketing of Real Estate Services

44

Viitanen (2004)

Brand in The Real Estate Business

Concept, Idea, Value

45

Chen et al

(2011)

Perceived Risk, Anticipated Regret

and Post-Purchase Experience in

The Real Estate Market: The Case

of China

47

Studies on

Service

Industries

Berry (2000) Cultivating Service Equity 49

Laroche et al

(2004)

Exploring How Intangibility

Affects Perceived Risk

50

Studies on

Luxury Brands

Hung et al

(2012)

Developing Experience-Based

Luxury Brand Equity in the Luxury

Resorts Hotel Industry

51

Keller (2009)

Managing the Growth Tradeoff:

Challenges and Opportunities in

Luxury Branding

52

57

CHAPTER 3

METHODOLOGY

3.1. Research Design

This study utilizes a descriptive and relational approach in analyzing the study

variables. It aims to identify the kind of relationships that exists between them and assess

how strong and how significant these relationships are. Given this approach, simple linear

regression analysis is sufficient to reach a valid conclusion. The set-up of independent

and dependent variables is illustrated in the Operational Framework. In simple tabular

form, the study variables and corresponding hypotheses are as follows:

Table 5: Independent and Dependent Variables

Hypothesis Independent

Variable

Dependent Variable

H1 Brand Equity Brand Preference

H2 Brand Equity Purchase Intent

H3 Brand Preference Purchase Intent

Nearly all data was collected using a survey instrument, which contains both

demographic/psychographic information as well as perceptions regarding brand equity

dimensions, brand preference, and purchase intent. Personal insights and exploratory

58

interviews with real estate brokers and/or executives supplemented the collected data as

the required by the analysis.

3.2. Population and Sample Sizes

The total number of units for all projects included in the scope of this study is

6,002. Based on a sales report by a reputable real estate company (name withheld per

request), about 50% of this population is expected to fall within the target age range of

40-60 years old. Furthermore, based on informal interviews with real estate brokers, it is

estimated that about 50% of the market is composed of value seekers. Taking all these

figures together, the estimated population size is about 1,500 people.

Sample size was derived based on tolerable margin of error and population size

using this formula:

n = ___ N___

(1+N*E

2

)

Where:

N = population size

E

2

= square of desired margin of error

Given 9% margin of error and a population size of 1500, a resultant sample size

of 115 respondents was derived. The required number of respondents per project was

59

computed based the relative number of units for each. For example, One Serendra

comprises roughly 12.4% of the study population (744 units in One Serendra / 6002 total

units). As such, 12.4% of the sample (115 * .124 = 15 respondents) is composed of One

Serendra unit owners. The same computation was applied to each project, and the

resultant figures are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6: Required Respondents per Project

Project Name Brand Number of

Units

% of

Population

Required

Respondents

One Serendra

Ayala Land

Premiere

744 12.4% 14

The Residences

at Greenbelt

Ayala Land

Premiere

1300 21.7% 25

Sonata Private

Residences

Robinsons

Luxuria

758 12.6% 15

The Gramercy

Residences

Century

Properties

950 15.8% 18

One Rockwell

Rockwell Land

Corporation

900 15.0% 17

Joya Lofts and

Towers

Rockwell Land

Corporation

400 6.7% 8

St. Francis

Shangrila Place

Shang

Properties

700 11.7% 13

Shang Grand

Tower

Shang

Properties

250 4.2% 5

3.3. Sampling Method

A random sampling method was utilized to select respondents. As indicated

earlier, respondents were limited to those in the selected demographic (class AB, 40-60,

60

Metro Manila resident) owning a premium condominium unit among those identified in

Table 4. In line with the findings of Gulas et al (2009), the sample need not be limited to

those actively searching a condominium unit, since situational involvement was shown

not to affect consumer understanding or recall of real estate brand messages.

Systematic sampling was performed. Respondents were sought out and contacted

through several brokers and sales agents who have sold units in the specified projects.

These brokers and sales agents consulted their databases in order to contact all eligible

respondents in alphabetical order and request their participation in the study. This process

went on until a sufficient number of respondents had been reached.

3.4. Survey Instrument

Demographic, Psychographic and Behavioral Information

The first part of the survey instrument includes demographic and psychographic

profiling information, as well as a few other behavioral items that aided in data analysis.

Most of this was used to validate respondent eligibility. Screening items include age,

income level, condo brands owned, and psychographic profiling statements.

For reference and further analysis, respondents were also asked to indicate which

income range they belong to, by choosing from a set of arbitrarily defined ranges. These

ranges are intentionally large since it was expected that respondents might not wish to

61

divulge specific information regarding their income. Despite this, it might have proven

useful to consider the differences between say, respondents with an income greater than

Php1,000,000 as opposed to those having an income of less than Php 180,000.

A simple approach to psychographic profiling was utilized. This involves having

respondents choose and rank statements that best describe their condominium purchase