Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Art1 Kitsch

Uploaded by

Lavinia Gherghina100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

26 views15 pagesArticol despre kitsch

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentArticol despre kitsch

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

26 views15 pagesArt1 Kitsch

Uploaded by

Lavinia GherghinaArticol despre kitsch

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 15

t~iipyrighi 2005 by the

Naponal An l^ucation Associaiion

Studin in An Educaiion

A Journal of Usucs and Rncin-h

2005. ^6(3), 197-210

What? Clotheslines and Popbeads Aren*t Trashy

Anymore?: Teaching About Kitsch

Kristin G. Congdon

I hiiuemty of Central Floritla

Doug Blandy

I hiiversity of Oregon

In rhis arricle, we explore changing definitions of kitsch and simultaneously

examine the relevance of kiisch to contemporary society. Using a number of

examples, including a focus on kitsch related to September 11, 2001, we explore

the current popularity of kitsch in society. We analyze rhe growth and influence

of kit.sch in everyday life and in che art world. We argue that kirsch makes our

pkiralism visible and that kirsch is a means to resist culturnl and aesthetic hege-

mony and power. Implications for art educarion are provided.

Kitsch, depending largely on context, can be defined in numerous ways.

For example. Art Nouveau is sometimes described as kitsch, often in a

degrading manner. It is thought to be decorative, filling a lower level

function in the modernist art world. In a recent exhibition, organized by

the Victoria and Albert Museum, an effort was made to reassess Art

Nouveau beyond rhe kitsch associated with its embellishment and orna-

mentation (Riding, 2000, p. AR23). While this exhibition attempted to

separate what the curators saw as the art form from rhe kirsch, it also

represented a missed opportunity to address the important social implica-

tions of kitsch, which will be discussed in this article. However, the

Victoria and Albert Museum exhibii is important because, until recently,

it was unusual for so-called fine art museums to deal with conceptions

and examples of kitsch.

Objects identified as kitsch are usually associ-

ated with items integrated into rhe everyday lives

of people. Consider, for example, the plastic pink

Ramingo, the velvet Elvis painting, or the Las

Vegas snow globe. Attitudes that people bring to

their appreciation of (or distaste for) kitsch will

vary. Kitsch may be revered as a treasured

memento of a significant event or be appreciated

with a sense of itony. In relation to the later, the

ubiquitous plastic flamingo is thought to be so

tacky (read as kitsch) that a current trend in Florida is to temporarily

place dozens of them as a joke in up-scale and conservatively landscaped

yards under cover of night (Erickson, 2000, pp. Al & A14; McCombs

2001, p. D4). Residents are said to have been "flocked." Kitsch can

Correspondence

rc^rding this article

may be sent to Kristin

G. Congdon ai the

Cultural Hcrilagc

AlliaJicc, School of Film

and Digital Media.

Univt-ruty of Central

Florida, Orlando, FL

32816. E-mail:

kcon gd o n

cc.ucg.cdu

Big Orange.

Photo by Bud Lee.

Studies in Art Education

197

Kristin G. Congdon and Doug Blandy

Clothesline.

Photo by Bud Lee

also be associated with gender, for example, a "girly" world like the world

of Betty Paige pin-ups, frilly lingerie from Frederick's of Hollywood, and

spiked high-heeled shoes are associated with fetnininitj' in the extreme.

Kitsch in the girly world can be so elaborate that ultra-feminine drag

queens are looked to for expertise, moving kitsch, in this case, towards a

cross-gender kind of experience (Bright, 1997. p. 132). Through its asso-

ciation with gender and sexual orientation, kitsch has also been linked

with "camp," partictilarly Sontag's (1961) delineation ot "camp" as anifi-

cial, ironic, playful, stylish, exaggerated, and theatrical. For Sontag, many

examples of camp are also kitsch. For Felluga (2004) camp is self-

conscious kitsch. Welch (2003) elaborates on the relationship between

kitsch and camp by arguing that camp amplifies kitsch by

focusing on... irony, aestheticism, theatricality and humor. For

example: A bed is not campy. A bed displayed as art is probably

kitschy. But a paint-splattered bed, previously occupied by two

men, hung on the wall, is definitely campy, (p. 1)

Kitsch is traditionally associated with bad taste. Kirschenblatt-Gimblctt

(1998) suggests looking

no farther than neighborhoods where...

certain property values will plummet with

appearances of clotheslines, satellite dishes,

storage sheds, birdbaths, or recreational

vehicles or the wrong types of lawn grass,

mailboxes, awnings, or siding material,

(p. 265)

Kitsch, a concept originating in the 19th centur)'

among German art dealers to describe bad art, is

commonly associated with fakes, aesthetic rubbish,

and that which is cheap. While (good) art is thought to require effort and

seriousness, kitsch is linked with pleasure and entertainment. Kuika's

(1996) conceptual analysis of kitsch as an aesthetic category supports

this view by identifying kitsch as being deficient and less valuable in

all ways than art.

Because of its association with bad taste, kitsch is devalued aestheti-

cally, economically, and culturally. Greenberg (1939) affirmed tbe devalu-

ation of kitsch within a modernist perspective in his now famous essay

"Avant-Garde and Kitsch," in which kitsch was linked with the aestheti-

cally undesirable, not suitable for cultivated people and identified as low

culture. Greenberg ultimately made "social snobbery look progressive"

(Gopnik, 1998, p. 73). Kirschenblatt-Gimblett (1998) amplifies

Greenberg's attitude towards kitsch by noting, "kitsch is to caste what

superstition is to religion--somebody else's mistake" (p. 276).

Kirschenblatt-Gimblett perceives that kitsch is not of the wealthy, academ-

ically educated populace. What is implicit in these attitudes towards kitsch

198 Studies in Art Education

Teaching About Kitsch

are values associated with a capitalist economy driven by mass production

and public consumption. Simply put, good taste is associated with those

who control the most capital and do not need to base consumption on

the afiordability promised by mass production.

Kammen (1999), a historian of culture, notes that correlations between

taste and social class were much discussed from the 1870s until after

World War IL However, beginning in the 1950s the relationship between

social class and cultural choices became more elusive. He attributes this

elusiveness to the development of more inclusive definitions of culture

and the fact that beginning in the 1960s increasing numbers of academi-

cally educated people participated in popular and mass culture.

Beginning in the late 20th century with the rise of post-modernism

and continuing into the 21st, attitudes towards kitsch have changed.

Kundcta (1988) was predictive of this change in attitude when he wrote

benevolently about kitsch in relation to human nature. For the novelist

Kundera;

Kitsch is the translation of the stupidity of received ideas into the

Linguage of beaury and feeling. It moves us to tears of compassion

for ourselves, for the banality of what we think and feel ...

(pp. 163-164)

Another reason for the change in attitude towards kitsch may be, as

Kirschenblatt-Gimblett (1998) suggests, that kitsch is a move toward

liberating pluralism, "an affirmation of the possibility of creative expres-

sion in all quarters" (p. 281). This observation by Kirschenblatt-Gimblett

is in keeping with our previous research associated with the contemporary

and historical human predisposition towards the "fake" (Congdon &

Blandy, 2001). In this research we examined the challenges and opportu-

nities associated with fakcry within the context of Gomez-Pena's (1996)

five worlds of contemporary life and art education. The cityscapes, music,

visual images, creative writing, and other examples of fakery that we

examined are considered kitsch within many traditional and/or modernist

definitions of the term. We concluded that youth culture characterized by

a voracious and self-conscious aptitude and appetite for sampling and

remixing from all the cultural detritus that surrounds us is contributing

significantly to redefining and newly defining life and material culture in

the 21st century. Postulating a liberating sixth world of critical engage-

ment and social reconstruction, we identified art educators as important

partners in working with children and youth to negotiate the inestimable

distractions and illusions associated with contemporary life. This work by

art educators and theit students in rhe sixth world would be informed by

those art educators writing over the past several decades who have assisted

[he held in formulatmg a critical pedagogy based upon methods of social

deconstruction and reconstruction.

Studies in Art Education 199

Kristin G. Congdon and Doug Blandy

Tourist with

Seashell. Photo

by Bud Lcc.

Our purpose in this article is to build on our conclusions associated

with the fake by focusing on kitsch. A-s a part ot this purpose we re.sist

defining kitsch and instead recognize kitsch as having clusters of meaning

associated with aesthetic, socio-cultural, economic, and political points of

view. Kitsch can appeal to all of the senses, and has

been closely linked with fakery, depravity, senti-

mentality, vulgarity, cra.ssness, and the formulaic,

but it is also about parody, irony, and satire.

Kitsch has been associated with low art, the uned-

ucated, and it is economically cheap, mass-

produced, and often considered tacky. It did not

fit into the realm of modernist tastes. Partly

because it has heen so debased and is now

enjoying an elevation in status, the critique of

kitsch stimulates our interest.

Our method of working with kitsch Is like that of the "mash-up" DJ

who juxtaposes samples of music pulled from multiple genres to recontex-

tualize and remix cultural expressions for the purpose of communicating

new meanings. We juxtapose and remix kitsch with questions and issues

long thoiighr important in our society and art education. In doing so, we

propose a place for kitsch within the context of educating children, youth,

and adults about att and material culture. In this article, our examples

will be broad based and include Latin American embellishment, responses

to the events of September 11 in New York, our contemporary collecting

frenzy, and the proliferation of tattooing. We look at reasons for teaching

our students various aspects of kitsch. We will focus on (1) analyzing the

popularity of kitsch; (2) viewing kitsch as liberating pluralism in the arts;

(3) recognizing kitsch as one strategy and aspect of cultural resistance; and

(4) suggesting implications for art education.

The Popularity of Kitsch

Kitsch perplexes and unnerves. Kitsch simultaneously repulses and

seduces by its apparent superficiality and appeal to baser instincts. Kitsch

is also perplexing because understanding and appreciating kitsch cannot

be reduced to simplistic claims such as it is all about "junk" or all about

"class." However, the perplexity associated with kitsch does not dissuade

people from appreciating and collecting it. It is likely that kitsch's appeal

may, in pan, be due to its resistance to classification.

In the April 30, 2002 issue of The New York Times, Matanowski

reported on a trend towards the passionate collecting of knickknacks.

bric-a-brac, and shotzkes. The popularity of PBS s Antiques Roadshow is

only one visual aspect of the current fi'enzy. Malanowski's article suggesLs

that perhaps one of the reasons for the show's popularity is that it pays

attention to everyday collectors who ordinarily gee little tespect or visi-

bility (pp. AR19 & AR23). It may be that one reason we are so drawn to

200 Studies in Art Education

Teaching About Kitsch

these collectors is because it is so hard explain why they collect what they

do. Malanowski writes:

The fact is that collectors are not so much nutty as inexplicahle;

the man who lives to hunt down rare decks of Canadian railroad

playing cards cannot explain why to someone to whom the cards are

just, you know, cards. Who can explain why Andy Warhol bought

200 cookie jars for $2 apiece, let alone why somebody bought 145

of them for $198,605 at the Warhol estate sale? (p. AR23)

It may be, Malanowski continues, that these collectors, when placed on

the Roadshow, are making a claim about having taste and intelligence.

You may have missed the dot.com boom, but those Eskimo hunting

masks that an ancestor acquired a century ago and that youVe been

storing behind the Christmas decorations ... [may be] worth a lot

more than your shares ofDrkoop.com. (Malanowski, 2000, p. AR19)

Partly because of this new interest in the everyday and "the great find,"

many universities are beginning collections that would have been unheard

of just a short time ago. The University of Cincinnati has mote than 300

snow globes; Ohio Stare University has accrued over 100 pairs of glasses

worn by celebrities; Western Michigan University collects antique hearing

aids; Northeastern University has nearly two dozen physical education

uniforms worn by women in the 1920s to the 1960s; and the University

of California at Davis has 10,000 shopping bags from all over the world

(Yachnin, 200I,p. A8).

Exhibitions that include kitsch are increasing as collections expand. In

2001, for example, the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture of the

Museum of New Mexico had an exhibition on "Tourist Icons: Native

American Kitsch, Camp and Fine Art Along Route 66." Included were a

necklace from the Santo Domingo Pueblo made from bits of battery

casings and red phonographic records instead of the usual precious stones;

numerous pairs of salt and pepper shakers; and miniature models of

pueblos and kivas (Brockman, 2001, p. AR26). More tecendy, the Studio

Museum in Harlem put on an exhibition titled "Black Romantic." Over

15,000 calls to artists went out nationwide resulting in a selection of

works described as "a kind of a Norman Rockwell-meets-George Hurrell

pictorial pridefest" (Plagens 2002, p. 62). Critic Peter Piagens writes,

"And there's some good stuff in it" (p. 62).

Besides giving collectors a positive identity and museums something

new to display and discuss, kitsch may be popular today because of its

nostalgic references. Much of it is inexpensive, and sometimes it comes

from recycling old items into something new, like using an old toilet or

bathtub as yard art. It is the ready-made that is manipulated and made

unique, granting it nostalgic aspects to past eras (Turner, 1996, p. 65).

While most all kitsch is questionable by elitist and classist standards,

Mexican kitsch may have been relegated to the lowest rung of kitschness

Studies in Art Education 201

Kristin G. Congdon and Doug Blandy

because "it is an already derivative producta Xerox of a Xerox"

(Stavans, 2000, p. B5). In other words, there is delight in the reproduc-

tion. Mexicans take American pop culture (unoriginal material culture)

and they copy it. When questioned why as a youth he enthusiastically

read the strips El Payo, KalimAn, and has Superrnachos, Stavans, a Spanish

professor at Amhert College, explains that as a child "|what] I wanted

most was salvation through escape to become a superheroa las mexi-

canapart mariachi and part Spiderman, to ridicule the political elite, to

travel to the Chiapas rain forest by horse with a flamboyant maid by my

side" (Stavans, 2000, p. B5). Kitsch, therefore, can unite you with a

mission, a dream, or a needed journey. In this regard kitsch liberates!

Kitsch as Liberating Pluralism

The material cultute of everyday life in a democracy Is associated with

the plurality of ways in which people assemble, work, and act together for

a variety of political, aesthetic, economic, familial, religious, and/or

educational purposes. In coming together to share celebratory experiences

of ever)'day events, people generate creative and symbolic forms such as

"custom, belief, technical skill, language, literature, art, architecture,

music, dance, drama, ritual, pageantry, handicraft..." (Bartis & Bowman,

2000). Participating in this way equips us with the ability to communi-

cate what is important; it grants refuge; it allows us to respond to the

problems and challenges associated with everyday life: it provides amuse-

ment and pleasure, and livelihood; and it exemplifies ingenuity. The incli-

nation to be creative is so ordinary that it is often overlooked for the

extraordinary contribution it makes to such commonplace activities as

cooking, fishing, keeping house, gardening, computing, and the multitude

of other endeavors required in daily life (Congdon & Blandy, 2003).

Depending upon one s point of view and/or the definitions that one is

sympathetic to, a great deal of what people are Inclined to make or appre-

ciate in the process of living their lives is a broad array of kitsch. This

inclination to embrace kitsch in this regard is profoundly exemplified in

the kitsch associated with the attack on the World I rade C'enter in New

York City on September 11, 2001.

In summer 2002. we visited "Ground Zero" in lowet Manhattan. Most

of the rubble had been removed from the area. What remained of the

New York World Trade Center's twin towers wetc the sunken walls or

"bath tub" engineered to keep the nearby East River at bay. Traces still

remained of the personal remembrances that visitors have left at the site,

although what we saw was much reduced ftom what was present in the

immediate days and weeks following the attacks. However, in keeping with

what can usually be found at pilgrimage sites, were numerous street

vendors selling September 11 paraphernalia. We saw all manner of stufi^ed

toys bearing 9/11 insignia of various types; key rings displaying the towers;

snow globes containing the towers; postcards of the towers' attack and

202 Studies in A rt Education

Teaching About Kitsch

aftermath; twin tower paperweights; commemorative books; all manner

of 9/11 t-shlrts and hats; New York City Police and Fire Department

memorabilia; American flags, and generally lots of red, white, and blue.

If mass production, vulgarity, gaudiness, emotional manipulation, and

cheapness characterize kitsch, then September 11 is clearly kitschified.

Some are outraged by this kitschification. A coast guard officer posted to

Salon.com that

Many of those I have served with take ptide in quiet resolve,

conscientious action, and muted yet sincere support of others. In

short, we refuse to be victims or buy into the commercialized veneer

oi Sept. 11 because we have a job to do for the American People,

and we know that no kitschy generalization will make that job go

away or make it any easier. (Hoerncmann, 2003)

The novelist Philip Roth wrote mournfully and nostalgically of visiting

the Twin Towers area shortly after their destruction and thankfully before

the "kitschification" we saw set in. He expressed his aversion and outrage

to this kitschification by saying that the only story he takes from 9/11

is the kitsch in all its horrornot the horror of what happened,

but the great distortion of what happened. It's almost embarrassing,

the kitschification of 3,000 people's deaths. Other cities have experi-

enced far worse catastrophes One wouldn't dream of slighting

these people, it Is awful, but we need to keep a sense of proportion

about these things. What we've been witnessing since September 11

is an orgy of national narcissism and a gratuitous sense of victimiza-

tion that is repellent. (Roth cited in Leigh, 2003, p. 1)

The disgust expressed by the coast guard officer and Roth about the

kitschification of 9/11 is consciously or unconsciously associated with a

very condescending and negative view of kitsch. While we need to tread

lightly here out of respect for those who see this kitschification of 9/11 as

aberrant and incongruent with their grief, we must also remember that

the negative connotations associated with kitsch may have more to do

with sexist, classist. and racist attitudes that contribute to an art/kitsch

dichotomy that were discussed earlier. Kitsch, in this way of thinking, is

about that which Is distasteful, base, and unthoughtful; it is something to

get rid of. However, when material culture, such as that now found at

Ground Zero, is considered from psychological, historical, sociological,

and anthropological perspectives, this dichotomy disintegrates except to

the extent that it illustrates a particular view among a certain group of

people at a particular time.

The kitschification of September 11 also memorializes September 11.

Kitsch as memorial is not at all uncommon. What would have been

surprising and disconcerting is if September 11 had not been kitschified.

Careful browsers in antique and junk stores will find that the attack on

Pearl Harbor, which September 11 is sometimes compared to, was

Studies in Art Education 203

Kristin G. Congdon and Doug Blandy

memorialized in emotionally laden posters Vk'ith tattered flags and admo-

nitions to "never forget" (Mieike, 2003). The United States' resulting

entry into World War II encouraged myriad forms of kitsch including

songs such as the "Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy." {Mieike, 2003). As a child,

[co-author of this article] Blandy discovered in his grandparents' base-

ment a mass-produced poster memorializing the RMS Titanic. If his

grandparents had been collectors of such memorabilia they might also

have had the sheet music associated with such songs as "It Was a Sad Day

When the Great Ship Went Down," and "Dovi-n With the Oid Canoe"

or ceramic models of the ship (Mieike, 2003).

Government entities in New York City are also moving to respond to

the events of September 11 through memorialization. Architects are

pondering how to officially memorialize the loss of life at the World

Trade Centers. The architect Hugh Pearman (2003) observes that

No one has yet thought of an appropriate way of memorializing

mass killing by terrorist action. Not only did no battle take place,

not only were no conventional weapons used, not only was this a

civilian affair, but even the enemy wa.s uncertain. So all the usual

supporting elements needed to generate a memorial are missing.

(p-3)

Memoriaiization is at least of two types: Those that are official and those

that are a spontaneous outpouring of grief. It is this latter type that inter-

ests us in relation to kitsch. Consider the thousands of plastic wrapped

flowers that appeared at Kensington Palace after the death of Princess

Diana. Several years ago we watched as a school yard fence in Sptingfield,

Oregon became a site for placing flowers, photographs, newspaper arti-

cles, handwritten notes, stuffed animals, balloons, and other miscella-

neous materials placed there to recognize those who were killed or

wounded in the Thurston High School shooting.

As the architects were planning, those thousands killed or injured in

rhe attack on the World Trade Center were immediately and sponta-

neously being memorialized through notes and pictures attached to the

surrounding walls. Shordy after the collapse of the Twin Towers street

vendors were selling items like those described earlier. Some people, as

one possible response to 9/11, are bringing the events of September 11

into their own lives through kitsch. This is not a passive response to the

event, bur an activist and liberating one. People are undoubtedly buying

these images and objects in order to deal with their stupefaction (Kundera,

1988) and as a way to personally memorialize rather than waiting for the

so-called experts and municipal officials to do it for them.

Clearly there Js no consensus around what constitutes appropriate grief

and/or a memorial response ro the attacks on the Twin Towers. Multitudes

of public responses, both ideological and practical, are circulating

consciously and unconsciouslyaround the issue. While some might

204 Studies in Art Education

Teaching About Kitsch

desire a consensus about what constitutes an appropriate response to

September 11 reached through reason, what is occurring are a plurality of

multiple, simultaneous, conflicting, and hotly debated responses appro-

priate to a pluralistic and democratic society.

Another example of kitsch's link to pluralism can be seen in Catholic

imagery found in church souvenir stands. No longer collected just by

Catholics, these items are used in up-scaled storefront windows and are

used as decorations in nightclubs. Olalquiaga, (1996) explains:

Suddenly, holiness is all over the place. For $3.25 one can buy a

Holiest Water Fountain in the shape of the Virgin, while plastic

fans engraved with the images of your favorite holy people go for

$1.95as do Catholic identification tags: 'I'm a Catholic. In case

of accident or illness please call a priest.' Glowing rosary beads can

be found for $125 and, for those in search of verbal illustrations,

a series of'Miniature Stories of the Saints' is available for only

$1.45.... Even John Paul II has something to contribute; on his

travels the Holy Father leaves behind a trail of images, and one can

buy his smiling face in a variety of Pope gadgets including alarm

clocks, pins, picture frames, T-shirts and snowstorm globes, (p. 271)

Olalquiaga continues to say that this "holy invasion" has now invaded the

galleries.

Many Latin American artists clutter their work with everyday objects

that communicate a brash and bold look. They play on stereotypes,

making a statement by being excessive. Sometimes they do this in order

to critique the powerful art establishment that has both disappeared and

invalidated their cultural aesthetic. Pep6n Osorio, for instance, is well

known for embellishing furniture and household items in an effort to

root his work in the social and political space of the Latin American

immigrant in the United States (Congdon & Hallmark. 2002). His art

hearkens back to a home country and purposely reflects a cultural bias

that dismisses a particular kind of aesthetic as it flies in the face of mini-

malism and the Puritanical dislike of decoration (Fusco, 1991). By

making visible another kind of aesthetic, artists like Osorio broaden the

art world and make its aesthetic more inclusive. He resists die dominant

art culture by playing up this aesthetic to an extreme.

Kitsch and Resistance

Greenberg's power as a critic established kitsch as a lowly person's

artistic taste. He claimed:

1 here has always been on che one side the minority of the powerful

-and therefore the cultivatedand on the other the great mass of

the exploited and poorand therefore the ignorant. Forma! culture

has always belonged to the flrst, while the last have had to contend

themselves with folk or rudimentary culture, or kitsch." (quoted in

Kirschenblatt-Gimblett, 1998, p. 279)

Studies in Art Education 205

Kristin G. Congdon and Doug Blandy

A Greenbergian perspective on the kitschification of September 11

would identify this phenomenon as one triore example of the "great mass"

of people turning to kitsch to express an uncultivated communicative

response. He might also negatively critique the work of Pepon Osorio.

We wonder what his response would be in this regard, co this kitschifica-

tion process as expressed on tbe body itself in the form of tattoos.

Anthropologists have informed us that "every culture's ideas about the

body both reflect and sustain ideas about the broader social and cultural

universe in which those bodies are located." (Benson, 2000, p. 234). It is

through our bodies that we make visible, to ourselves and others, what we

are." (Benson, 2000, p. 235). In this regard, as recognized by Foucault,

"the body is always 'directly invoived in a political field', its training and

its intelligibility always of concern; the politics of the body is always a

practical politics, a question of power as well as epistemology." (Foucault

cited in Benson, 2000, p. 235)

Memorializing September 11 through kitsch imagery and objects is

vividly expressed in the plethora of September 11 tattoos and tattoo flash

that is appearing nationwide. Frequenting the vendors in lower

Manhattan convinces us that the kitschification of September 11 includes

body customization through the appropriation of the images oi

September 11 tbat are being mass produced and sold on the streets.

The history of tattooing in the United States has always included the

appropriation of images from folk and popular culture (Govenar. 2000).

Tattooist Don Ed Hardy claims, "...tattooing is the greatest art of

piracy Tattoo artists have always taken images from anjxhing available

that customers want to have tattooed on them" (Hardy cited in Benson.

2000, p. 243). The place to see the most tattoos in Portland. Oregon is

tbe Hawthorne neighborhood. If you walk this street on a hot afternoon

you will see a plethora of tattoos with imagery culled from comic strip

characters, team mascots, anime and manga characters, movie and rock

stars, among others. The history of tattooing in the United States has also

always included tattoos as memorials. During the Wotld War I era a very

common tattoo was the "Rose of No-Man's Uuid." This tattoo wa.s based

on both a World War I popular song and the image of a Red Cross nurse

(Govenar, 2000). The quintessential stereotype of a tattoo may be a

banner inscribed with "mother" surrounded by roses and/or swallows.

Tattoos responding to September 11 routinely appear in publications

such as International Tattoo and Skin and Ink. A recent exhibit of

photographs titled "Indelible Memories" at Historic Richmond Town on

Staten Island in New York records tattoos wotn in the region that

commemorates September 11. The photographs, taken by Vinnie Amesse,

document a plethora of images that include porrraits of the deceased, fire-

fighter badges, patriotic symbolism, angels, doves and views of the towers,

among others. In this circumstance, whether we agree witb the sentiments

206 Studies in Art Education

Teaching About Kitsch

or not, imagery, that Roth (Roth cited in Leigh, 2003) would identify as

kitsch, is being used by some ro affirm their own relationship to the

events of September 11 while simultaneously resisting terrorism and offi-

cial memorialization. Consider this in relationship to one petson's

description of being tattooed as

the puncturing, cutting and piercing of the skin: the flow of blood

and the infliction of pain; the healing process, a visible and perma-

nent mark on yet underneath che skin: 'an inside which comes from

the outside ... the exteriorization of the interior which is simultane-

ously the interiorization of the exterior. (Gell cited in Benson, 2000,

p. 237)

September 9/11 tattoos can be seen as a person's way of communi-

cating his or her values, attitudes, and beliefs about the event on the only

surface that can truly be called their own. In chis regard, unlike any offi-

cial memorializing that may take place, the memorial is the person. The

tattoo is also the reference point from which a person can see him or

herself within a historical event felt to be of importance (Benson, 2000).

From this perspective, reality is both shaped and expressed by the tattoo.

People are remarkable in the ways that they are able to u.se culture as a

tool to advance a political agenda and resist hegemony. While we

routinely accept that so-called art can be a part of cultural resistance,

definitions and conceptions of kitsch usually fail to mention this possi-

bility. The 9/11 tattoos remind us of the importance that the body can

have as a site of resistance. We can also study the kitschification of

September 11 in relation to the larger history of resistance, The tattooed

body can be thought of as contributing to those public spaces chat

ptomote an issue but also empower: they build self and group

identities They offer versions of experience and reality, becoming

part of the stories people tell each other: to console, galvanize and

resist. (Duncombe, 2002, p. 8)

The kit.schificaiion of 9/11 mostly may have to do with people taking

images and objects manufactured for the general public and using them

to generate a cultural response of their own. It is important that you not

read our speculations about the kicsch of 9/11 as a valorization of this

particular kitschification process; rather, it is simply illustrative. To date,

there is no consensus around the political implications of 9/11. Resistance

in response to 9/11 is about wanting to make a statement about safety

and security among some, and, sadly, resistance to democratic values

associated with a free society among others.

Implications for Art Education

fCitsch has not been explicitly considered to any great extent within

the literature of art education. This is surprising given that the study of

popular and mass culture has been overwhelmingly accepted within the

Studies in An Education 207

Kristin G. Congdon and Doug Blandy

Field particularly in relation to the study of material and visual culture.

Clearly, what has been called "kitsch" is deeply rooted in issues related to

aesthetics, gender, culture, class, economics, race and ethnicity, and poli-

tics; all of which are integral to the study of material and visual culture.

Even if one rhinks of ir as "bad art," its prevalence makes it relevant to arr

education curricula. Additionally, because so much kitsch is enjoyed,

appropriated, and consumed by youth, it requires attention in our class-

rooms and curricula at all levels of education. As Brown (2003) points our

although kitsch is a "popular" phenomenon, there's .some crossover

among those doing the theorizing and those doing the consuming

the consumption of kitsch artifacts is perhaps most prominent

among young college-educated men and women whose cultural

practices are often difficult to classify.

As art educators we should partner with out students to learn about

kitsch. Our learning .should include the myriad definitions of kitsch,

recognizing that even within and among definitions there will he multiple

and conflicting views on the topic. We should critique such definitions in

relation to the personal and public interests that they represent. Our

thinking about kitsch should recognize that it will he understood and

appreciated variously depending upon the historical, political, economic,

social, and cultural contexts in which it is being discussed and created.

Our learning must also recognize new ways of thinking about kitsch and

the appropriation of kitsch for a multitude of purpo.ses.

Clotheslines and popbeads aren't necessarily trashy anymore. They tell

us about a specific time and place. The visibility of these items and others

like them provide art educators with the means to expand on aesthetic

dialogues, address statements of resistance to the dominant culture, give

presence and agency to a diverse group of voices, and debate and

construct the power of economics in the art world. They, and the other

forms of visual and material culture once only thought to he kitsch, and

rendered invisible or marginalized because of a perceived lack of worth,

should now be recognized as a part of that larger cultural ooze, compost,

sludge, and atmosphere that in combination forms our cultural commons.

Tt is in this common space that our learning partnership with students can

penetrate, subvert, and/or leap across the border between reified and

hegemonic definitions and conceptions of cultural products and practices

into what we have referred to earlier as the sixth world (Congdon &

Blandy, 2001). In this world of critical pedagogy, kitsch becomes one

more source from which students and teachers can sample, mix, appro-

priate, recycle, overlay, agitate, critique, and ultimately reconstruct their

physical and mental environment for the purpose of creating compelling

arguments and new narratives.

208 Sttuiies in Art Educaiion

Teaching About Kitsch

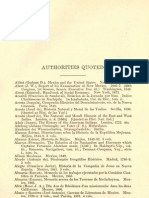

References

Bjrtis, ['., & Bowman, I'. (2000). A teacher's guide tofblktife resourees for K-12 classrooms [online].

Available from World Wide Web; htip://Icweb.loc.gov/folklife/reachers.html

Benson, S. (2000). Inscriptions of the self-rcflecdon on tattooing and piercing in contemporary

Euro-America. In J. Caplin (Ed.), Written on the body: The tattoo in European and American

history (pp. 234-254). Princeton. NJ: Princeton University.

Bright, S. (1997). Sexual state of the union. New York: Simon and Schiuter.

Brociunan, J. (2001, September 2). Don't jeer at the .souvenirs; They may be the teal deal. The

New York Times. AR26.

Btown, S. (2O03). On kitsch, nostalgia and nineties femininity. Retrieved March 28, 2003 from

bttp://www. middlecnglisb .org/spc/siKissues/22.3/brown. bt ml

Ciingdon. K. G.. & Biandy, D. (2001). Approaches to the real and the fake; Living iJfe in the fifth

world. Studies in Art Education, 42{3). 266-278.

Congdon . K, G.. & Blandy, D. (2003). Administering the culture of everyday life: Imagining the

future of arts secior administration. In V. B. Morris & D. B. Pankrar/ (Eds.). The arts in a

new millennium: Research and the arts sector (pp. 177-188). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Congduti, K. G., & Hallmark. K. K. (2002). Artists from Latin American cultures. Westpon, CT:

Greenwood Press.

[buncombe. S. (2002). Culsurat resistance reader. New York: Vctso.

Erickson, S. (2000. Septembet 2). Eicnial migration. The Orlando Sentinel, M & Al4.

Fclluga, D. (2004). Camp. Retrieved July 2, 2004 From

h ttp: //www. sla.puidue.cdu/academicycngl/theory/ posimodernismy tenns/catnp .html

Fusco, C. (1991, December). Vernacular memories. Art in America, 9B-\0i & 133.

Gomei-Pena. C. (1996). T/jc new world border: Prophecies, poems & letjueras for the end of the

century. San Francisco: City Lights.

tlopnik. A. (1998, March 16). The power critic. TheNetv Yorker, 70-78.

tiovcnar, A. (2000). The changing image oi tattooing in American culture, 1846-1966. In J.

Capian (Ed.), Written on the body: The tattoo in European and American history dp^. 212-233).

Princeton. NJi Princeton University.

Greenbcrg, C. (1939). Avant-garde and kit.sch. Partisan Review, 6(5), 34-49.

Hoernemann, E. (2003). Letter in response to the Kitschiftcation of 9/11 by Daniel Harris.

Salon.com Retrieved March 28. 2003 from

http://archive.salon.coni/ncws/leners/2002/OI/28/kitsch/

Kammcn. M. (\999). American culture, American tastes. Social change and the 20th century. New

York, NY: Knopf

Kjrschenblatt-Gimblett, B. (1998). Destimtion culture: Tourism, museums and heritagi. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

Kulka, T. (1996). Kitsch and art. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Kundera, M. (1988). The an ofthtnoveL New York: Grove,

l^igh, 5. (2003). PhilipRothattacks' otgy of narcissism' post Sept I I. The Daily Telegraph.

Retrieved March 28, 2003 from

htt p://www.telegrapb.co.uk/news/main.jhtm!?xml=/news/2002/10/05/wlindh205.!tml

Malanowski, J. (2000, April 30). When knickknacks turn into a collective passion. The New York

r(w. ARI9&AR23.

Studies in Art Education 209

Krisrin G. Congdon and Doug Blandy

McCombs, P. (2001, May 2'J). Flamingo trazc ha.spink leg to stand on. Orlando SetitineL D-t.

Mielke. V. (2003). 9/11: Pop cubure and remctnbrance. Retrieved March. 28, 2003 from

hiEp://septterror. tripod.tom/aboutsi[c_2.html

Otajquiaga, C. (1996). Holy kitschen: Col leering ret iginu.? junk from the street. In G. Mosquera

(Ed.), Beyond the fanltutk: Contemporary an critkiiin Frgm LMIIII Amerira (p^^. 270-288).

Cambridge, MA: MIT Prtss.

Pcarman, H. (2003). The need fir menwriak Retrieved March 28, 2003 from http;//www.hugh-

peartnaii.com/anicles2ymemorials.html

Plagens. P. (2002, May 6). Kitsch as kitsch can. Newsweek. 62-63.

Riding, A. (2O00, April 30). Beyond kitsch: A new look at An Nouveau. TIK New York Times.

AR23.

Stavans. I. (2000, September 22). L.ctters to ihe editor. Tbe Chrotikle of Higher Education. B5.

Sontag, S. (1961). Agairur ittter/iirtatioii and otfKr essays. New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux.

Turner. K. (1996). Hacer Cosas: Recycled arts and the makings of identity in Texas-Mcxicati

culture. In C. Cerny & S. ScriiT(Eds.). Recycled reseem Folk art fiom the global sa-ap lieap {^p.

60-71). New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Welch, J. D. (2003). Camp iconography and gender performance by Boh Rauscf}enberg: 1955-61.

Rettieved Augu.st 29. 2003 from bttpi//kitschparadc.ath.cx/wri/camp.phtml

Yachnin, J. (2001, May 25). An embarrassment oi' riches. The ChronkU of Higher Educamn, A8.

' 0 Studies in Art Education

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- 10.developing A Global Management CadreDocument31 pages10.developing A Global Management CadremnornajamudinNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Organisational Theory - DisneyDocument7 pagesOrganisational Theory - DisneyAmy Adriana HallNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Zin 100 CoreosDocument23 pagesZin 100 CoreosLaura Perez HoyosNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- DDDDocument3 pagesDDDNeelakanta YNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Engl 112 Reading and Writing SkillsDocument600 pagesEngl 112 Reading and Writing Skillscj altamiaNo ratings yet

- Appendix 3 Lesson Plan of Experimental GroupDocument15 pagesAppendix 3 Lesson Plan of Experimental GroupRotua Serep SinagaNo ratings yet

- History: HollywoodDocument14 pagesHistory: HollywoodLakshanmayaNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Peace Ship 2011 Expedition Altai, Baikal - Olkhon Island, Ulan-Ude, Alkhanai - Zabaykalye SIBERIA - RUSSIA 30 June - 26 July 2011Document15 pagesPeace Ship 2011 Expedition Altai, Baikal - Olkhon Island, Ulan-Ude, Alkhanai - Zabaykalye SIBERIA - RUSSIA 30 June - 26 July 2011Boris PetrovicNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Inside FAANG - Behind The Scenes PDFDocument32 pagesInside FAANG - Behind The Scenes PDFRahul RajputNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Alag RPH Task PerformanceDocument3 pagesAlag RPH Task PerformanceKyle MampayNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Modern Drummer January 2014Document5 pagesModern Drummer January 2014Bartholomew Aloicious MumfreesNo ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis On William GoldingDocument31 pagesA Critical Analysis On William GoldingHafiz AhmedNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- AOL and Time Warner A Classic FailureDocument2 pagesAOL and Time Warner A Classic FailureBetaa TaabeNo ratings yet

- Mise en Abyme As A Representation of TraumaDocument5 pagesMise en Abyme As A Representation of TraumaLarissa MuravievaNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- PIPPIN: The Fosse LinesDocument11 pagesPIPPIN: The Fosse LinesGibson DelGiudice100% (2)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Answer Sheet in General Mathematics: Name: Grade&SectionDocument2 pagesAnswer Sheet in General Mathematics: Name: Grade&SectionKenneth SalivioNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- CHS June 2011-2Document2 pagesCHS June 2011-2Alexandros CharkiolakisNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Section: Text and Discourse LinguisticsDocument6 pagesSection: Text and Discourse LinguisticsHuay Mónica GuillénNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Tribes of ChhattisgarhDocument10 pagesTribes of ChhattisgarhNishant JhaNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- About The Roman Frontier On The Lower DaDocument19 pagesAbout The Roman Frontier On The Lower DaionelcpopescuNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- 1992 A Strange Liberation - Tibetan Lives in Chinese Hands by Patt S PDFDocument267 pages1992 A Strange Liberation - Tibetan Lives in Chinese Hands by Patt S PDFIgor de PoyNo ratings yet

- Housing SAUDI ARABIA - AbstractDocument5 pagesHousing SAUDI ARABIA - AbstractSarah Al-MutlaqNo ratings yet

- Guide To The GuildsDocument34 pagesGuide To The GuildsargentAegisNo ratings yet

- Exploration of Patriarchy With Reference To The Woman Characters in R.K. Narayan's Novel The GuideDocument4 pagesExploration of Patriarchy With Reference To The Woman Characters in R.K. Narayan's Novel The GuideIjahss JournalNo ratings yet

- New Perspectives On 'The Land of Heroes and Giants' The Georgian Sources For Sasanian History - Stephen H. Rapp JR PDFDocument32 pagesNew Perspectives On 'The Land of Heroes and Giants' The Georgian Sources For Sasanian History - Stephen H. Rapp JR PDFZanderFreeNo ratings yet

- Erich Elisha SamlaichDocument11 pagesErich Elisha SamlaichDushan MihalekNo ratings yet

- V 01 AuthDocument33 pagesV 01 AuthRussell HartillNo ratings yet

- Secondary Courses - The National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS)Document1 pageSecondary Courses - The National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS)Subhankar BasuNo ratings yet

- Grammar of Kannada 00 Kittu of TDocument500 pagesGrammar of Kannada 00 Kittu of Tprash_neoNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)