Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hypertension

Uploaded by

WanAzrenCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hypertension

Uploaded by

WanAzrenCopyright:

Available Formats

Introduction

If an individuals resting blood pressure is persistently high, it not only

puts a strain on the heart but also damages the walls of the arteries,

making them stiffer and more prone to clogging and haemorrhage. This

causes problems in the organs they supply and leads to potentially fatal

conditions and debilitating disorders, such as coronary heart disease

and stroke.

Hypertension, defined as a persistent raised blood pressure of

140/90mmHg,

1,2,3

is one of the most common disorders in the UK.

*

Although it rarely causes symptoms on its own, the damage it does to

the arteries and organs can lead to considerable suffering and

burdensome healthcare costs. Hypertension is arguably the most

important modifiable risk factor for coronary heart disease (the leading

cause of premature death in the UK) and stroke (the third leading

cause). It is also an important cause of congestive heart failure (heart

strain) and chronic kidney disease. This has earned hypertension a

reputation as the silent killer, making it a key priority for prevention,

detection and control, and one of the most important challenges facing

public health today.

Despite isolated examples of good practice, a truly joined-up approach

to tackling hypertension is lacking, particularly around prevention,

early detection and clinical protocols for control. It is therefore critical

that primary care staff and local multi-agency teams work together to

establish programmes which not only identify and treat people with

hypertension but actively promote healthy lifestyles and implement

preventive strategies in order to meet the challenge of tackling

hypertension

Footnote: Blood pressure is expressed as two numbers eg. 140/90mmHg 140 is the

systolic pressure (highest pressure during each pulse) and 90 is the diastolic pressure

(lowest pressure). It is measured in millimetres of mercury (mmHg).

*Thresholds for hypertension in people with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes are slightly lower.

Hypertension the Silent Killer

Bri ef i ng St at ement

H

y

p

e

r

t

e

n

s

i

o

n

t

h

e

S

i

l

e

n

t

K

i

l

l

e

r

H

y

p

e

r

t

e

n

s

i

o

n

t

h

e

S

i

l

e

n

t

K

i

l

l

e

r

2

Hypert ensi on t he Si l ent Ki l l er

Faculty of Public Health Briefing Statement

Evidence

The associated risks of hypertension increase

gradually in parallel with rising blood pressure. A

large-scale international study has shown that

significantly increased risks of cardiovascular

disease begin to appear at a level as low as

115/75mmHg

5

far lower than the current average

adult blood pressure (eg. England average:

131/74mmHg for men and 126/73mmHg for

women).

6

The threshold of 140/90mmHg (as a diagnosis of

hypertension) has been designated to indicate when

a particular course of action should be instituted,

such as intervening medically.

1,2,3

Effects of hypertension on health

Hypertension is usually symptomless and often not

regarded as a disease in its own right. However, it is

a major risk factor in a number of potentially fatal

conditions and debilitating disorders:

Coronary heart disease

Stroke

Heart failure

Chronic kidney disease

Aortic aneurysm

Retinal disease

Peripheral vascular disease

Prevalence of hypertension

In England, 32% of men and 30% of women, aged

16 years or over, have hypertension.

6

The equivalent

figures for Scotland are 33% of men and 28% of

women.

20

There are no exactly comparable figures

for Wales or Northern Ireland. However, 15% of

adults in Wales reported being treated for high blood

pressure.

7

In Northern Ireland, 19% of men and

27% of women reported having been diagnosed with

high blood pressure.

8

Risk factors for hypertension

Although hypertension is itself a risk factor for a

number of conditions, (see above) there are also

risk factors both unmodifiable and modifiable

which predispose certain people to developing

hypertension.

Unmodifiable risk factors

Age and gender

The association between increasing age and

increasing systolic blood pressure is thought to

reflect the length of time people are exposed to

modifiable risk factors. For any given age up to 65

years women tend to have a lower blood pressure

than men. After 65 years, this trend is reversed.

6

The cause is unknown. Prevalence also increases

with age.

Ethnicity

Hypertension is more prevalent in different ethnic

groups, such as black Caribbean men and women,

and less prevalent in Bangladeshi men and women,

for example.

9

Some of the differences in prevalence

are thought to be related to inherited differences in

the way the body reacts to salt

10

and in blood

pressure controlling hormones.

Main risk factors for

developing hypertension*

Unmodifiable Modifiable

Age and gender Excess salt

Ethnicity Overweight and obesity

Physical inactivity

Excess alcohol

Diabetes

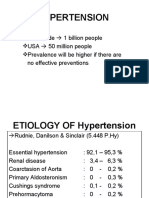

Five main types of hypertension

4

Essential (or primary): accounts for 95% of cases of hypertension in the UK. No specific underlying cause

but thought to result from a genetic predisposition in addition to the cumulative

effects of various lifestyle factors eg. salt intake, physical inactivity.

Secondary: accounts for up to 5% of cases. Caused by an underlying disease, most commonly

chronic kidney disease, or as a side-effect of medication.

Malignant (or accelerated): a very high or rapidly rising blood pressure which threatens end-organ damage and

requires urgent or emergency treatment. About 1% of those with essential

hypertension develop malignant hypertension.

Gestational: occurs during pregnancy and usually returns to normal following childbirth.

White-coat: occurs when a persons blood pressure is high when they see a doctor or nurse, but

is normal at other times.

* This is not an exhaustive list of risk factors. For a full list see

Easing the Pressure: Tackling Hypertension

4

3

Hypert ensi on t he Si l ent Ki l l er

Faculty of Public Health Briefing Statement

Modifiable risk factors

Excess salt

Evidence has shown a strong association between

salt intake and elevated blood pressure.

11

In the UK,

65-70% of the salt we eat comes from processed

foods such as bread, cereals, ready meals etc.

11

Average adult daily intake is 9g of salt per day

three times the amount actually needed.

12

The daily

recommended level is 6g for adults representing

what is actually achievable across the population, not

what is optimal. For children, different thresholds

have been set according to age.

11

Overweight and obesity

Obesity multiplies the risk of developing

hypertension about fourfold in men and threefold in

women.

13

It is well documented that levels of

overweight and obesity have increased over the last

decade. In the UK, about two-thirds of men and over

half of women are either overweight (BMI of 25-

29.9kg/m

2

) or obese (BMI of 30kg/m

2

).

4

Physical inactivity

People who do not take enough aerobic exercise (eg.

running, walking and cycling) are more likely to

have or to develop hypertension. Large cross-

sectional and longitudinal studies have shown a

direct positive correlation between habitual aerobic

physical inactivity and hypertension.

14

59% of men

and 72% of women in Scotland,

15

and 70% of men

and 74% of women in Northern Ireland do not meet

physical activity guidelines.

8

In Wales, 14% of adults

do not exercise,

16

and in England, only 37% of men

and 24% of women meet recommended levels.

6

Excess alcohol

Blood pressure rises when large amounts of alcohol

are consumed, particularly when binge-drinking.

Heavy alcohol use is a well-established risk factor for

hypertension and stroke. A large study of almost

6,000 men, aged 35-64 years, followed-up for 21

years, found that there was a strong correlation

between alcohol consumption and mortality from

stroke.

17

Diabetes

Hypertension is more prevalent in people with Type

1 and Type 2 diabetes than in the non-diabetic

population (whether they are overweight or not), as

a consequence of kidney damage and insulin

resistance respectively. In England, as many as 70%

of adults with Type 2 diabetes have hypertension,

doubling the risk of a cardiovascular event.

4

Costs

In addition to the suffering caused to patients,

carers and their families, as a consequence of

hypertension, there is also a considerable cost

burden to the NHS, social care and the wider

economy. It is extremely difficult to calculate the

proportion attributable to hypertension. However,

with regard to the main consequences coronary

heart disease and stroke it has been calculated

that total costs are equivalent to about 7.06bn for

coronary heart disease, and 5.77bn for stroke.

16

Prevention

There is an increasing body of evidence to support

various lifestyle changes to prevent hypertension.

There are two approaches to preventing

hypertension:

Whole population

The aim is to prevent hypertension by lowering

average blood pressure by relatively small amounts

across a whole population. It has been estimated

that a reduction as small as 2mmHg in average adult

systolic blood pressure could save more than 14,000

UK lives per year.

18

This can be achieved by

encouraging enough people to change their lifestyles

sufficiently to reduce their blood pressure.

Main lifestyle changes include:

Reduce salt intake (to an average of 6g/day for

adults)

11

Increase fruit and vegetable intake

Increase habitual physical activity to

recommended levels

Keep alcohol intake within recommended

benchmark limits

Control weight

At-risk individuals or groups

This approach focuses on those known to be at

higher risk of developing hypertension. The risk

factors described above, and further explained in

Easing the Pressure: Tackling Hypertension,

4

can be

used to identify target individuals and groups. For

example, focus could be on those who are

overweight or obese, or those from particular ethnic

communities who have an increased risk of

hypertension (see Ethnicity p.2).

4

Hypert ensi on t he Si l ent Ki l l er

Faculty of Public Health Briefing Statement

Detection and control

Detection

The task of identifying those adults with existing

hypertension is a daunting one and in a general

practice setting it makes sense to priorities those

patients at high overall risk of cardiovascular

disease, or who show signs or symptoms of target-

organ damage that may be due to, or exacerbated

by, hypertension. There are three main ways of

identifying patients with hypertension known as

case-finding:

Opportunistic case-finding in various settings

often undertaken during a consultation on

another health matter, or in settings such as

health fairs, workplaces etc.

Systematic screening programmes usually

based on a proactive call-recall programme.

Targeted case-finding in general practice

focuses on patients most likely to have

hypertension or complications from it.

Well-maintained disease registers are necessary

for successful implementation.

Control

Evidence shows that lowering blood pressure in

people with hypertension is associated with a

reduction in cardiovascular disease risk. A

large-scale meta-analysis of observation prospective

studies among hypertensive patients aged 40-69

years showed that a 20mmHg lower systolic blood

pressure is associated with:

5

less than half the risk of dying from a stroke, and

half the risk of dying from coronary heart

disease.

It is important that clinical decisions about

whether and how to treat hypertensive patients

are based on both their blood pressure level and

overall cardiovascular risk not on blood

pressure alone. Please refer to appropriate clinical

guidelines. The key guidelines that provide clinical

protocols for instituting therapies, including drug

therapy, to control hypertension are produced by the

British Hypertension Society, NICE and Scottish

Intercollegiate Guideline Network.

1,2,3

As a consequence of poor detection and diagnosis,

many people with hypertension go untreated or

receive inadequate treatment the proportion of

those untreated tends to be higher in older people

and manual socioeconomic groups.

4

The National

Service Frameworks (NSFs) and GMS contract

provide incentives to address this.

Adherence and concordance

Of those who are diagnosed, only 10% are

controlled to the target of 140/90mmHg.

19

This is

due to poor practitioner understanding of treatment

regimens, and to patients not taking medication as

prescribed known as poor adherence. Poor

adherence to prescribed medications is the most

important cause of uncontrolled blood pressure.

Reasons for this include forgetfulness, difficulty in

reading written instructions or in opening medicine

bottles.

Concordance means shared decision-making and

agreeing a plan of treatment that best represents

the intentions of both the patient and clinician. It is

an important step in motivating patients to take

their medicines as prescribed. Agreements should

be supported with written information, a care plan

and patient-held record. This issue is explored by

the Medicines Partnership Organisation (see Useful

Organisations p.6).

Policy Context

There are numerous policy drivers at both national

and local level which are relevant to hypertension.

Easing the Pressure: Tackling Hypertension gives

details of relevant policies and strategies.

4

However,

key drivers include:

England: The NSFs for Coronary Heart Disease,

Older People, Diabetes and Renal Services all have

standards relevant to the prevention, detection and

control of hypertension.

The public health white paper, Choosing Health,

builds on the NSFs. It introduces a number of new

initiatives including tough targets for salt reduction

in processed foods, nutrient-based standards for

public sector catering and specialist anti-obesity

services in primary care trusts.

The Department of Health Public Service Agreement

sets objectives to substantially reduce mortality

rates from the major killer diseases as well as

improve health outcomes for people with long-term

conditions. It also aims to halt the year-on-year rise

in obesity among children. The Priorities and

Planning Framework 2003-2006 also requires

practice-based registers to be updated to ensure

patients with CHD and diabetes receive appropriate

advice. National Standards, Local Action: Health and

Social Care Standards and Planning Framework

2005/06-2007/08 sets national targets and

standards for NHS and social services authorities.

Scotland: Improving Health in Scotland: the

Challenge Framework for Action sets targets for

improving the life expectancy and health-life

expectancy of all adults.

The Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke Strategy

for Scotland recommends that all NHS boards

should develop explicit CHD and stroke prevention

strategies to target groups classed as high risk

including those with hypertension.

The white paper, Towards a Healthier Scotland, sets

targets for CHD, stroke, physical activity, diet and

alcohol, to improve those life circumstances that

impact on health.

Wales: The white paper, Improving Health in

Wales: A Plan for the NHS with its Partners sets the

direction for health services in Wales, including

increasing the power of local health groups to

deliver strong community-based health and social

care services.

To reduce deaths from CHD, Tackling Coronary

Heart Disease in Wales: Implementing through

Evidence requires everyone at high risk of

developing, or who have been diagnosed with, CHD

to have access to a multifactorial risk assessment

and appropriate treatment.

Northern Ireland: The Investing for Health strategy

aims to improve the health and well-being of people

in Northern Ireland including reducing the mortality

rate from circulatory diseases, in particular heart

disease and stroke.

The Northern Ireland Evidence-based Stroke Strategy

provides a challenging agenda for the development of

stroke services over the next 5-10 years.

International: The World Health Report 2002:

Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life describes

the burden of disease, disability and death that can

be attributed to a small number of health risks,

including blood pressure.

Recommendations

The prevention, detection and control of

hypertension are essential to national strategies

concerned with CHD, stroke, diabetes, chronic

kidney disease and the health of older people. The

following recommendations can help local multi-

agency teams implement strategies to tackle

hypertension at local level:

Establish a local hypertension action team, with

key partners including health services, local

authorities and voluntary organisations for

example, to develop a local hypertension

strategy. Easing the Pressure: Tackling

Hypertension gives comprehensive guidance on

how to go about this.

4

Undertake a service review or audit of local

services to identify current activity, gaps,

priorities and possible opportunities for service

development.

Review and agree local clinical guidelines and

protocols on the detection, treatment and

management of hypertension. The review

should consider national guidance as well as

reflect local circumstance. Ensure guidelines

have local ownership, including primary and

secondary care.

Develop comprehensive local programmes to

promote healthy eating and physical activity.

Support local primary care practitioners

through regular practice visits to advise on

developing at-risk registers, call-recall rotas,

prescribing, IT systems, staffing issues, and

additional resources.

Produce patient information to explain the risks

of hypertension and give advice on the various

interventions and treatments to prevent and

reduce blood pressure.

Hold local events and meetings to raise

awareness of hypertension, such as local health

fairs, awareness days. Encourage people to

know their number (ie. their blood pressure

level). These events could be targeted at

specific groups and give relevant lifestyle

advice.

Set local standards for public sector catering

services such as schools, NHS, to include

recommendations on salt levels.

5

Hypert ensi on t he Si l ent Ki l l er

Faculty of Public Health Briefing Statement

The Faculty of Public Health has produced, in association

with the National Heart Forum, Easing the Pressure:

Tackling Hypertension a toolkit for developing a local

strategy to tackle high blood pressure.

4

Supported by the

key organisations involved in tackling hypertension, the

toolkit provides local health improvement teams with the

essential building blocks to develop an effective

programme for the prevention and control of hypertension.

An online resource has also been developed and includes

a ready-reckoner to help calculate local prevalence, and

checklists to help identify gaps and monitor progress (see:

www.fph.org.uk/Publications). Easing the Pressure

forms part of a wider campaign of work aimed at promoting

healthier lifestyles to reduce disease burden through the

production of toolkits on the wider determinants of health

including physical activity, obesity, food poverty and fuel

poverty. The Faculty also advocates on salt reduction as

part of its salt strategy.

References

1 Williams B, Poulter NR, Brown MJ et al.

2004. Guidelines for management of

hypertension: report of the fourth

working party of the British

Hypertension Society, 2004-BHS IV.

Journal of Human Hypertension; 18:139-

85

2 National Institute for Clinical Excellence

(NICE). 2004. Hypertension:

Management of Hypertension in Adults

in Primary Care. Clinical Guideline

No.18. London: NICE

3 Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines

Network (SIGN). 2001. Hypertension in

Older People. A National Clinical

Guideline. SIGN Publication No.49.

Edinburgh: SIGN

4 Maryon-Davis A, Press V on behalf of the

Faculty of Public Health and National

Heart Forum. 2005. Easing the Pressure:

Tackling Hypertension. A toolkit for

developing a local strategy to tackle

high blood pressure. London: Faculty of

Public Health

5 Prospective Studies Collaboration. 2002.

Age-specific relevance of usual blood

pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-

analysis of individual data for one

million adults in 61 prospective studies.

Lancet; 360: 1903-12

6 Joint Health Surveys Unit. 2004. Health

Survey for England 2003. Volume 2. Risk

factors for cardiovascular disease.

London: The Stationery Office

7 National Assembly for Wales. Welsh health

Survey 1998. Results of the Second

Welsh Health Survey. 1999. Newport:

Government Statistical Service

8 Northern Ireland Statistics and Research

Agency (NISRA). 2002. Northern Ireland

Health and Social Wellbeing Survey

2001. Belfast: NISRA

9 Joint Health Surveys Unit. 2000. Health

Survey for England. The Health of

Ethnic Minority Groups 99. London: The

Stationery Office

10Stewart JA, Dundas R, Howard RS et al.

1999. Ethnic differences in incidence of

stroke: prospective study with stroke

register. British Medical Journal; 300:

967-72

11Scientific Advisory Committee on

Nutrition. 2003. Salt and Health. London:

Department of Health

12Henderson L, Gregory J, Swan G. 2002.

National Diet and Nutrition Survey:

Adults Aged 19-64. Volume 1. London:

The Stationery Office

13National Audit Office. 2001. Tackling

Obesity in England. London: The

Stationery office

14Paffenbarger RS Jr, Jung DL, Leung RW,

Hyde RT. 1991. Physical activity and

hypertension: an epidemiological view.

Annals of Medicine; 23: 319-27

15Physical Activity Task Fore. 2003. Lets

Make Scotland More Active. A Strategy

for Physical Activity. Edinburgh: Scottish

Executive

16Liu JLY, Maniadakis N, Gray A, Rayner M.

2002. The economic burden of coronary

heart disease in the UK. Heart; 88: 597-

603

17Hart CL, Smith D, Hole DJ, Hawthorne M.

1999. Alcohol consumption and

mortality from all causes, CHD and

stroke: results from a prospective

cohort study of Scottish men with 21

years of follow up. BMJ; 318: 1725-29

18Critchley J, Capewell S. 2003. Substantial

potential for reductions in CHD

mortality in the UK through changes in

risk factor levels. Journal of

Epidemiology and Community Health; 57:

243-47

19Brown MJ, Cruickshank JK, Dominiczak AF.

2003. Better blood pressure control:

how to combine drugs. Journal of Human

Hypertension; 3: 53-9

20Joint Health Surveys Unit on behalf of the

Scottish Executive. 2000. The Scottish

Health Survey 1998. London: The

Stationery Office.

Publications

Easing the Pressure: Tackling

Hypertension (2005)

Online resource

www.fph.org.uk

Choosing Health: Making Healthy Choices

Easier (2004)

National Service Frameworks for Coronary

Heart Disease (2000), Diabetes (2001),

Older People (2001), Renal Services (2005)

National Standards, Local Action: Health

and Social Care Standards and Planning

Framework 2005/06-2007-08 (2004)

Public Service Agreement (2002)

Priorities and Planning Framework

2003-06 (2002)

Department of Health

www.dh.gov.uk

Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke

Strategy for Scotland (2002)

Improving Health in Scotland: the

Challenge Framework for Action (2003)

Towards a Healthier Scotland (1999)

Scottish Executive

www.scotland.gov.uk

Improving Health in Wales: A Plan for the

NHS with its Partners (2001)

National Assembly for Wales

www.wales.gov.uk

Tackling Coronary Heart Disease in Wales:

Implementing through Evidence (2001)

National Health Service for Wales

www.wales.nhs.uk

Investing for Health (2002)

Department of Health, Social Services and

Public Safety

www.dhsspsni.gov.uk

Northern Ireland Evidence-based Stroke

Strategy (2001)

Northern Ireland Chest, Heart and Stroke

Association

www.nichsa.com

6

Hypert ensi on t he Si l ent Ki l l er

Faculty of Public Health Briefing Statement

World Health Report 2002: Reducing

Risks, Promoting Healthy Life

World Health Organization

www.who.int/en

Useful Organisations

Blood Pressure Association

www.bpassoc.org.uk

British Heart Foundation

Heart Information Line: 08450 70 80 70

www.bhf.org.uk

British Hypertension Society

www.hyp.ac.uk

Consensus Action on Salt and Health

www.actiononsalt.org.uk

Diabetes UK

Helpline: 020 7424 1030

www.diabetes.org.uk

Food Standards Agency

www.food.gov.uk

Medicines Partnership Taskforce

www.medicine-partnership.org

National Heart Forum

www.heartforum.org.uk

National Institute of Health and Clinical

Excellence

www.nice.org.uk

National Kidney Federation

Helpline: 0845 601 0209

www.kidney.org.uk

Stroke Association

Helpline: 0845 30 33 100

www.stroke.org.uk

Acknowledgments

Authors:

Dr Alan Maryon-Davis FFPH FRCP

Convener, Cardiovascular Health Working

Group, Faculty of Public Health

Lindsey Stewart (and Series Editor)

Faculty of Public Health

Produced by:

Faculty of Public Health

4 St Andrews Place

London NW1 4LB

t: 020 7935 3115

e: healthpolicy@fph.org.uk

w: www.fph.org.uk

Registered charity no: 263894

ISBN: 1-900273-19-5

Published May 2005. The information provided in

this statement is correct at time of going to press.

Design and print: www.fosterandlisle.co.uk

Summary

This briefing gives an overview of the burden of

hypertension including the implications for

health and the cost to individuals, society and

the NHS. It also makes important

recommendations for action that can be

implemented at local level. It is not intended as

an exhaustive resource but as a signpost to the

key evidence, publications and organisations as

a next step to understanding and tackling this

important public health issue.

You might also like

- TransplantationDocument11 pagesTransplantationmardsz100% (1)

- Colorectal CancerDocument23 pagesColorectal Cancerralph_gail100% (1)

- Ischaemic Heart Disease Mku 2020Document38 pagesIschaemic Heart Disease Mku 2020ElvisNo ratings yet

- Acute Kidney InjuryDocument37 pagesAcute Kidney InjuryLani BuenaventuraNo ratings yet

- Left-Sided Congestive Heart Failure Case PresentationDocument64 pagesLeft-Sided Congestive Heart Failure Case PresentationNicole Villanueva, BSN - Level 3ANo ratings yet

- Addisonian Crisis: Manish K Medical Officer IgmhDocument47 pagesAddisonian Crisis: Manish K Medical Officer IgmhNaaz Delhiwale100% (1)

- PancreatitisDocument59 pagesPancreatitisAarif RanaNo ratings yet

- Implementing NICE guidance for hypertension case scenariosDocument51 pagesImplementing NICE guidance for hypertension case scenariosrwev3No ratings yet

- What Are Electrolytes? What Causes Electrolyte Imbalance?: Fast Facts On ElectrolytesDocument11 pagesWhat Are Electrolytes? What Causes Electrolyte Imbalance?: Fast Facts On ElectrolytesL InfiniteNo ratings yet

- Anal FistulaDocument26 pagesAnal FistulaBeverly PagcaliwaganNo ratings yet

- Seminar: Pere Ginès, Aleksander Krag, Juan G Abraldes, Elsa Solà, Núria Fabrellas, Patrick S KamathDocument18 pagesSeminar: Pere Ginès, Aleksander Krag, Juan G Abraldes, Elsa Solà, Núria Fabrellas, Patrick S KamathcastillojessNo ratings yet

- Effects of a Sedentary LifestyleDocument9 pagesEffects of a Sedentary LifestylethomasNo ratings yet

- Disorders of The EyeDocument16 pagesDisorders of The Eyelisette_sakuraNo ratings yet

- Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS)Document21 pagesHyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS)Malueth AnguiNo ratings yet

- PANCREATITISDocument38 pagesPANCREATITISVEDHIKAVIJAYANNo ratings yet

- HypertensionDocument20 pagesHypertensiondocbayNo ratings yet

- Congestive Heart FailureDocument74 pagesCongestive Heart FailureNiharikaNo ratings yet

- NCP Incarcerated Inguinal HerniaDocument3 pagesNCP Incarcerated Inguinal HerniaAHm'd MetwallyNo ratings yet

- Diabetes NotesDocument10 pagesDiabetes Notestripj33No ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis: An Autoimmune Neurologic DisorderDocument16 pagesMyasthenia Gravis: An Autoimmune Neurologic DisorderHibba NasserNo ratings yet

- Pulmonary EmbolismDocument80 pagesPulmonary EmbolismVarun B Renukappa100% (1)

- Identify CVD Risk in the Office with Framingham & Non-Fasting TestsDocument28 pagesIdentify CVD Risk in the Office with Framingham & Non-Fasting TestsJuwanto Wakimin100% (1)

- SCI (Spinal Cord Injury)Document51 pagesSCI (Spinal Cord Injury)Awal AlfitriNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Enzyme StudiesDocument4 pagesCardiac Enzyme StudiesDara VinsonNo ratings yet

- Myocardial Infarction. BPTDocument62 pagesMyocardial Infarction. BPTAanchal GuptaNo ratings yet

- Acute Pancreatitis: J Koh & D ChengDocument7 pagesAcute Pancreatitis: J Koh & D ChengGloriaaaNo ratings yet

- SepsisDocument33 pagesSepsisv_vijayakanth7656No ratings yet

- Heart Failure Case Study 1 Fall 2014 JeremyDocument5 pagesHeart Failure Case Study 1 Fall 2014 Jeremyapi-264487290No ratings yet

- Abdominal Aortic Aneurysmn FINAL WORDDocument16 pagesAbdominal Aortic Aneurysmn FINAL WORDErica P. ManlunasNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Arrest CPR GuideDocument54 pagesCardiac Arrest CPR GuideIdha FitriyaniNo ratings yet

- LeukemiaDocument23 pagesLeukemiaSrm GeneticsNo ratings yet

- Hypertension - Clinical: DR Teh Jo Hun AzizahDocument32 pagesHypertension - Clinical: DR Teh Jo Hun AzizahAzizah AzharNo ratings yet

- Managing Hypertension in PregnancyDocument20 pagesManaging Hypertension in PregnancyRelly Arevalo-AramNo ratings yet

- Cancer NursingDocument53 pagesCancer Nursingfairwoods100% (1)

- Biliary DisoderDocument50 pagesBiliary DisoderZanida ZainonNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Mellitus Complications GuideDocument48 pagesDiabetes Mellitus Complications GuideAnditha Namira RS100% (1)

- Acute Abdominal Pain Case: AppendicitisDocument70 pagesAcute Abdominal Pain Case: AppendicitisVenny VeronicaNo ratings yet

- Cerebrovascular Accident: "A Case Study Presentation"Document35 pagesCerebrovascular Accident: "A Case Study Presentation"Kristine YoungNo ratings yet

- By: Calaour, Carrey Dasco, Danica Amor Dimatulac, Kevin Lim, Shiela Marie Pagulayan, Sheena May Pua, Mar KristineDocument41 pagesBy: Calaour, Carrey Dasco, Danica Amor Dimatulac, Kevin Lim, Shiela Marie Pagulayan, Sheena May Pua, Mar Kristineceudmd3d100% (2)

- Myocardial Infarction: Practice Essentials, Background, Definitions PDFDocument12 pagesMyocardial Infarction: Practice Essentials, Background, Definitions PDFMukhtar UllahNo ratings yet

- Pericarditis NCLEX Review: Serous Fluid Is Between The Parietal and Visceral LayerDocument2 pagesPericarditis NCLEX Review: Serous Fluid Is Between The Parietal and Visceral LayerlhenNo ratings yet

- Aneurysm PDFDocument20 pagesAneurysm PDFKV100% (1)

- What Is Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument16 pagesWhat Is Rheumatoid ArthritisDurge Raj GhalanNo ratings yet

- Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaDocument5 pagesBenign Prostatic HyperplasiajustmiitmiideeNo ratings yet

- Management of CholeraDocument69 pagesManagement of CholeraNatalia LawrenceNo ratings yet

- Pulmonary Embolism Guide: Causes, Symptoms & DiagnosisDocument60 pagesPulmonary Embolism Guide: Causes, Symptoms & DiagnosisRafika RaraNo ratings yet

- Care PlanDocument26 pagesCare PlanChevelle Valenciano-GaanNo ratings yet

- Lipid Profile Disease DiagnosisDocument31 pagesLipid Profile Disease DiagnosisGeetanjali Jha100% (1)

- Lung Cancer ScreeningDocument17 pagesLung Cancer ScreeningNguyen Minh DucNo ratings yet

- Emergency Management of DKADocument12 pagesEmergency Management of DKAtinzioNo ratings yet

- COLORECTAL CANCER: SIGNS, STAGES, RISK FACTORS & TREATMENTDocument31 pagesCOLORECTAL CANCER: SIGNS, STAGES, RISK FACTORS & TREATMENTIrene RealinoNo ratings yet

- Understand Diabetes Mellitus Types, Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentDocument22 pagesUnderstand Diabetes Mellitus Types, Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentEman KhammasNo ratings yet

- Diabetic KetoacidosisDocument4 pagesDiabetic KetoacidosisAbigael Patricia Gutierrez100% (1)

- Different Diagnostic Procedure of Typhoid Fever ADocument8 pagesDifferent Diagnostic Procedure of Typhoid Fever AdjebrutNo ratings yet

- Burn Injury PathophysiologyDocument1 pageBurn Injury PathophysiologyMonique Ann DanoyNo ratings yet

- CaseDocument15 pagesCaseNuzma AnbiaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Systolic Hypertension in The Elderly: R Gupta, RR KasliwalDocument7 pagesUnderstanding Systolic Hypertension in The Elderly: R Gupta, RR KasliwallolitlolatNo ratings yet

- 8731 ch03Document37 pages8731 ch03Mohammed Salim AmmorNo ratings yet

- How Alcohol Raises Blood PressureDocument4 pagesHow Alcohol Raises Blood PressureAlessandraNo ratings yet

- AnalysisDocument8 pagesAnalysisJovita Gámez de la RosaNo ratings yet

- Terapi CairanDocument12 pagesTerapi CairanWanAzrenNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledapi-61200414No ratings yet

- WHO Dengue Guidelines 2013Document160 pagesWHO Dengue Guidelines 2013Jason MirasolNo ratings yet

- Basic Chest Radiology ArticleDocument16 pagesBasic Chest Radiology ArticleUsman ShahidNo ratings yet

- DeathbyStrangulation DR - DeanhawleyDocument9 pagesDeathbyStrangulation DR - DeanhawleybaetyNo ratings yet

- WHO Dengue Guidelines 2013Document160 pagesWHO Dengue Guidelines 2013Jason MirasolNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Splenic TraumaDocument6 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Splenic TraumaArdel RomeroNo ratings yet

- Myocardial Infarction: Signs and SymptomsDocument5 pagesMyocardial Infarction: Signs and SymptomsKelly OstolNo ratings yet

- Global Citizens AssignmentDocument9 pagesGlobal Citizens Assignmentapi-658645362No ratings yet

- Medical Tribune May 2013Document39 pagesMedical Tribune May 2013Marissa WreksoatmodjoNo ratings yet

- Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Benefits for Prior MI PatientsDocument40 pagesDual Antiplatelet Therapy Benefits for Prior MI PatientsKarren Taquiqui PleteNo ratings yet

- VeslimDocument26 pagesVeslimAbhishekNo ratings yet

- Diabetes The NumbersDocument24 pagesDiabetes The NumbersSasikala RajendranNo ratings yet

- Joseph A. Ladapo, M.D., Ph.D. Curriculum Vitae Business InformationDocument33 pagesJoseph A. Ladapo, M.D., Ph.D. Curriculum Vitae Business InformationWCTV Digital TeamNo ratings yet

- Heart Failure Care Plan LippincottDocument62 pagesHeart Failure Care Plan LippincottDyllano100% (1)

- Research Essay Vongsy 1Document10 pagesResearch Essay Vongsy 1api-509641593No ratings yet

- University For Development Studies: WWW - Udsspace.uds - Edu.ghDocument149 pagesUniversity For Development Studies: WWW - Udsspace.uds - Edu.ghAmeliaNo ratings yet

- The Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular HealthDocument20 pagesThe Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular HealthResti Eka SaputriNo ratings yet

- Hawthorn (Crataegus SPP.) in The Treatment of Cardiovascular DiseaseDocument10 pagesHawthorn (Crataegus SPP.) in The Treatment of Cardiovascular DiseaseAnonymous EAPbx6No ratings yet

- Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire 2020Document3 pagesPhysical Activity Readiness Questionnaire 2020freyang esperanzaNo ratings yet

- Iups Programa 25072017 BXDocument76 pagesIups Programa 25072017 BXSonja BuvinicNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Non Communicable DiseasesDocument35 pagesIntroduction To Non Communicable DiseasesNayyar Raza Kazmi100% (1)

- Substance Abuse Treatment and Care For WomenDocument107 pagesSubstance Abuse Treatment and Care For WomenLjilja Taneva100% (1)

- QR Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (5th Edition) PDFDocument8 pagesQR Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (5th Edition) PDFKai Xin100% (1)

- Eating Activity Guidelines For New Zealand AdultsDocument87 pagesEating Activity Guidelines For New Zealand AdultsCharli HarrisonNo ratings yet

- NPCDCS Final Operational GuidelinesDocument78 pagesNPCDCS Final Operational GuidelinesTitiksha KannureNo ratings yet

- Sodium Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors in The Treatment of Diabetes MellitusDocument21 pagesSodium Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors in The Treatment of Diabetes MellitusManuel PérezNo ratings yet

- Ayusante CatalogueDocument12 pagesAyusante CatalogueAnkit Modi0% (1)

- NCP Nutrition Assesment MatrixDocument22 pagesNCP Nutrition Assesment MatrixPoschita100% (1)

- Why Women Live Longer Than MenDocument21 pagesWhy Women Live Longer Than MenKavitha Bahu ReddyNo ratings yet

- Improve Health and Fitness Goals Through Regular Exercise (EED119Document6 pagesImprove Health and Fitness Goals Through Regular Exercise (EED119Skarzy Abajar100% (1)

- Reading ComprehensionDocument6 pagesReading ComprehensionShanti SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- A Healthy Cholesterol 2011 Final PDFDocument20 pagesA Healthy Cholesterol 2011 Final PDFAli K SheqlawaNo ratings yet

- Hypertension SlidesDocument166 pagesHypertension SlidesStella CooKeyNo ratings yet

- New Approach For CV Risk Management (Prof. DR - Dr. Djanggan Sargowo, SPPD, SPJP (K) )Document56 pagesNew Approach For CV Risk Management (Prof. DR - Dr. Djanggan Sargowo, SPPD, SPJP (K) )Yulia SumarnaNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 New Syllabus NotesDocument69 pagesUnit 1 New Syllabus Notesmalak sherif100% (1)

- Physical Education Chapter - 3Document15 pagesPhysical Education Chapter - 3pragatiNo ratings yet