Professional Documents

Culture Documents

State's Brief

Uploaded by

Stephen PopeCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

State's Brief

Uploaded by

Stephen PopeCopyright:

Available Formats

No.

WR-79302-01

In the

Court of Criminal Appeals

For the

State of Texas

No. 744824-A

In the 351

st

District Court

Of Harris County, Texas

MAURA WIGGINS LEVINE

Applicant

V.

THE STATE OF TEXAS

Respondent

RESPONDENTS BRIEF

DEVON ANDERSON

District Attorney

Harris County, Texas

JOSHUA A. REISS

Assistant District Attorney

Harris County, Texas

1201 Franklin, Suite 600

Houston, Texas 77002

Tel.: 713/755-5826

Fax No.: 713/755-5809

Reiss_josh@dao.hctx.net

SBOT#: 24053738

Counsel for the State of Texas

ORAL ARGUMENT REQUESTED

COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS

AUSTIN, TEXAS

Transmitted 4/28/2014 9:26:39 AM

Accepted 4/28/2014 12:23:18 PM

ABEL ACOSTA

CLERK

April 28, 2014

2

IDENTITY OF PARTIES AND COUNSEL

Maura Levine (the applicant).

Counsel for the applicant: Randy Schaffer, The Schaffer Firm, 1301

McKinney, Suite 3100, Houston, Texas 77010.

Counsel for the State: Assistant District Attorney Joshua A. Reiss, Harris

County District Attorneys Office, 1201 Franklin Street, Suite 600, Houston, Texas

77002.

3

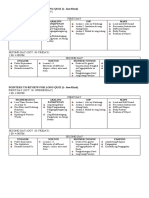

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES ...................................................................................... 5

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .................................................................................. 8

ISSUES PRESENTED .............................................................................................10

STATEMENT OF FACTS ......................................................................................12

A. States Evidence at Guilt-Innocence ...........................................................12

B. Defenses Evidence at Guilt-Innocence ......................................................13

C. The Applicants Testimony .........................................................................14

D. Defense Counsels Closing Argument ........................................................16

E. Jury Charge and Deliberations ....................................................................18

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ......................................................................19

ARGUMENT ...........................................................................................................22

DEFENSE COUNSEL DID NOT RENDER DEFICIENT

PERFORMANCE FOR FAILURE TO REQUEST A MISTAKE OF FACT

JURY INSTRUCTION WHEN THE LAW IS UNSETTLED REGARDING

WHETHER THE INSTRUCTION IS ALWAYS NECESSARY IN ORDER

TO GIVE EFFECT TO THE STATUTORY DEFENSE ..............................23

A. Bruno v. State Creates an Unsettled Legal Environment .........................24

B. Okonkwo v. State Recognizes as Unresolved the Necessity of Requesting

a Mistake of Fact Jury Instruction to Give Effect to the Defense When

the State Must Prove the Mens Rea Beyond a Reasonable Doubt ...........28

C. Defense Counsel Did Not Render Deficient Performance in an Unsettled

Legal Environment ...................................................................................31

4

DEFENSE COUNSELS ASSERTION THAT HIS FAILURE TO

REQUEST A MISTAKE OF FACT INSTRUCTION WAS

INADVERTENT RATHER THAN STRATEGIC DOES NOT

DEMONSTRATE DEFICIENT PERFORMANCE .......................................32

A. Defense Counsels Affidavit is Unpersuasive .........................................33

B. Defense Counsels Affidavit is Insufficient to Support the Habeas

Courts Deficient Performance Finding ...................................................36

THE APPLICANT FAILS TO DEMONSTRATE STRI CKLAND

PREJUDICE BECAUSE THE JURY CONSIDERED HER MISTAKES OF

FACT ...................................................................................................................41

THE JURY CHARGE DID NOT EFFECTIVELY PREVENT THE

APPLICANT FROM PRESENTING A MISTAKE OF FACT DEFENSE 45

PRAYER ..................................................................................................................49

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE AND COMPLIANCE ...........................................51

5

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Barajas v. State, No. 05-93-00042-CR, 1995 WL 519352, at *3 (Tex. App.

Dallas Aug. 28, 1995, no. pet.) (mem. op., not designated for publication) ........23

Barbar v. State, 167 Tex. Crim. 48 (1958) ..............................................................20

Bruno v. State, 845 S.W.2d 910 (Tex. Crim. App. 1993) (plurality opinion) . passim

Cooks v. State, 5 S.W.3d 292 (Tex. App. Houston [14th Dist] 1999, no pet.) .....38

Estrada v. State, 313 S.W.3d 274 (Tex. Crim. App. 2010) .....................................36

Ex parte Levine, No. WR-79302-01, 2014 WL 792080 (Tex. Crim. App. Feb. 26,

2014) (order, not designated for publication) ...................................................5, 17

Ex parte Reed, 271 S.W.3d 698 (Tex. Crim. App. 2008) ........................................31

Ex parte Smith, 296 S.W.3d 78 (Tex. Crim. App. 2009).........................................27

Ex parte Weinstein, 421 S.W.3d 656 (Tex. Crim. App. 2014) ................................31

Ex parte Welch, 981 S.W.2d 183 (Tex. Crim. App. 1998) ......................................27

Gardner v. State, 780 S.W.2d 259 (Tex. Crim. App. 1989) ....................................21

Grant v. State, No. 09-94-181-CR, 1998 WL 809413 (Tex. App.- Beaumont Nov.

18, 1998) ...............................................................................................................23

Griffith v. State, 315 S.W.3d 648 (Tex. App. Eastland 2010, pet. refd) .............38

Guerrero v. State, No. 01-11-00091-CR, 2012 WL 1564670 (Tex. App. Houston

[1st Dist.] May 3, 2012, no pet.) (mem. op., not designated for publication) ......23

Guzman v. State, 955 S.W.2d 85 (Tex. Crim. App. 1997) ......................................31

Hopson v. State, No. 14-08-00735-CR, 2009 WL 1124389 (Tex. App. Houston

[14

th

Dist.] Apr. 28, 2009, no. pet.) (mem. op., not designated for publication) .23

6

Levine v. State, No. 07-00-0155-CR, 2001 WL 43052 (Tex. App. Amarillo, Jan.

16, 2001, no pet.) (mem. op., not designated for publication) ............................... 4

Louis v. State, 393 S.W.3d 246 (Tex. Crim. App. 2012) ............................ 16, 40, 41

Mays v. State, 318 S.W.3d 368 (Tex. Crim. App. 2010) .........................................35

Okonkwo v. State, 357 S.W.3d 815 (Tex. App. Houston [14

th

Dist.] 2011, pet.

granted) .......................................................................................................... 26, 32

Okonkwo v. State, 398 S.W.3d 689 (Tex. Crim. App. 2013) .......................... passim

Posey v. State, 966 S.W.2d 57 (Tex. Crim. App. 1998) ..........................................42

Reyes v. State, No. 10-12-00205-CR, -- S.W.3d --, 2013 WL 5872738 (Tex. App.

Waco Oct. 31, 2013, pet. refd) ............................................................................38

Sands v. State, 64 S.W.3d 488 (Tex. App. Texarkana 2001, no pet.) ..... 22, 23, 51

Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668 (1984) .............................................. passim

Thompson v. State, 236 S.W.3d 787 (Tex. Crim. App. 2007) .................................40

Thompson v. State, 93 S.W.3d 16 (Tex. Crim. App. 2001) .....................................22

Traylor v. State, 43 S.W.3d 725 (Tex. App. Beaumont 2001, no. pet.) ........ 22, 23

Turner v. State, No. 04-03-00436-CR, 2004 WL 1881748 (Tex. App. San

Antonio Aug. 25, 2004, no pet.) (mem. op., not designated for publication) ......23

Vasquez v. State, 830 S.W.2d 948 (Tex. Crim. App. 1992) (per curiam) ...............35

Wesbrook v. State, 29 S.W.3d 103 (Tex. Crim. App. 2000)....................................22

STATUTES

TEX. CODE CRIM. PROC. art. 36.14..........................................................................42

TEX. PENAL CODE 8.02 ............................................................................ 17, 32, 43

TEX. PENAL CODE 19.02(b)(1),(2) ......................................................................... 4

TEX. PENAL CODE 19.04 ......................................................................................... 4

7

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Applicants Brief in Support of Writ ........................................................................19

Applicants Writ ................................................................................................ 17, 24

Applicants Writ Exhibit No. 2, Affidavit of Don Catlett .................................. 28, 29

Finding of Fact No. 7 ...............................................................................................28

Finding of Fact No. 14 .............................................................................................19

Finding of Fact No. 26 .............................................................................................36

States Original Answer .................................................................................... 17, 31

States Trial Exhibit 28A ............................................................................................ 7

TREATISES

43 George E. Dix & John M. Schmolesky, Texas Practice: Criminal Practice and

Procedure 43.36 (2013) .....................................................................................33

8

TO THE HONORABLE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS:

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The applicant was charged by indictment for first-degree felony murder.

TEX. PENAL CODE 19.02(b)(1),(2). A jury found the applicant guilty of second-

degree felony manslaughter. TEX. PENAL CODE 19.04. The trial court imposed a

twenty year sentence in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice Correctional

Institutions Division.

The applicant filed a direct appeal contesting the trial courts order to

cumulate her manslaughter conviction with a separate conviction for attempted

murder, and the trial courts denial of a mistrial motion after the State improperly

impeached a defense witness. The Seventh Court of Appeals affirmed the

applicants conviction. Levine v. State, No. 07-00-0155-CR, 2001 WL 43052

(Tex. App. Amarillo, Jan. 16, 2001, no pet.) (mem. op., not designated for

publication).

The applicant filed this original application for writ of habeas corpus on

May 17, 2012. On February 28, 2013, the Hon. Mark Kent Ellis, 351

ST

District

Court, adopted Applicants Revised Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of

Law and recommended to the Court of Criminal Appeals that habeas corpus relief

be granted.

9

On February 26, 2014, the Court of Criminal Appeals entered an order for

the parties to brief whether Okonkwo v. State, 398 S.W.3d 689 (Tex. Crim. App.

2013), affects analysis of the instant applications merits. Ex parte Levine, No.

WR-79302-01, 2014 WL 792080 (Tex. Crim. App. Feb. 26, 2014) (order, not

designated for publication).

10

ISSUES PRESENTED

(1) Mistake of fact is a statutory defense that negates the mens rea. In

Okonkwo, the Court of Criminal Appeals acknowledged that the law is unsettled

regarding whether a defense counsel must always request a mistake of fact jury

instruction in order give effect to the defense. Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 695-96.

Did defense counsel render ineffective assistance for failure to request a mistake of

fact jury instruction when the law is unsettled?

(2) Defense counsels affidavit represents that his failure to request a

mistake of fact jury instruction was inadvertent rather than strategic. In

Okonkwo the Court of Criminal Appeals considered a similar affidavit and

concluded that defense counsels failure to request a mistake of fact jury

instruction was constitutionally reasonable. Id. at 696-97. Pursuant to Okonkwo,

is defense counsels affidavit determinative of deficient performance?

(3) In Okonkwo the concurrence determined that the appellant did not

demonstrate prejudice caused by defense counsels failure to request a mistake of

fact jury instruction: The jury obviously rejected appellants claim of an honest or

good-faith mistake by finding him guilty. If the jury rejected that claim, then it

inexorably follows that it would have rejected . . . that appellant made an honest

mistake and that his mistake was a reasonable one. Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 702

(Cochran, J., concurring) (emphasis in original). Pursuant to the Okonkwo

11

concurrence, was the applicant prejudiced by defense counsels failure to request a

mistake of fact instruction when the jury considered and rejected her mistake of

fact claim by finding her guilty of manslaughter?

(4) In Okonkwo the Court of Criminal Appeals did not address the States

argument that defense counsel was not ineffective because the State was required

to prove the mens rea beyond a reasonable doubt and a mistake of fact instruction

was subsumed by the charge and merely negated an element the State was

required to prove. Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 695. The jury charge in the instant

application directed the jurors to consider all the evidence, instructed that the

State must prove the mens rea beyond a reasonable doubt, and required the

applicant be acquitted if the State failed to meet its burden of proof. Was the

applicant effectively prevented from presenting a mistake of fact defense by the

absence of a mistake of fact instruction in the jury charge?

12

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. States Evidence at Guilt-Innocence

The applicant was indicted and tried for the murder of complainant Bill

Robins (Robins) by striking the complainant with a deadly weapon, namely an

automobile (C.R. at 2). The State introduced a redacted copy of the applicants

written statement in which she acknowledged killing Robins by pinning him

against a brick wall with the hood of her car:

While at the dead end of the drive way, I stopped the car

and Billy got out. He was by the drivers side door and

he continued to yell at me. I thought he was going to go

home at this point. But he went to the front of the car

and he sort of leaned over the front of the car and this is

when he threw the glass at my car. The glass hit my

windshield. I guess it deflected off my windshield.

When Billy threw the glass, the car went forward and I

acidently [sic] pinned Billy against a brick wall. I backed

up right a way [sic] and I looked and I couldnt believe

that I had actually hit him with the car, when I had meant

to back out and away from him.

States Trial Exhibit 28A at 3-4 (bloc text removed).

To counter the applicants assertion of an accident, the State introduced

evidence of acceleration marks measuring 7 and 9 (IV R.R. at 32). These marks

were left in a straight line and reflected that the applicants car hit the wall at an

angle without any indication that she attempted to turn her wheel away from

Robins who was near a wall when he was struck (VI R.R. at 82) (VII R.R. at 165).

13

According to the States expert who testified at trial, in order to leave acceleration

marks of this length the applicants car had to be accelerated to approximately

3,700 RPMs while in neutral and then shifted into drive (VI R.R. at 131-37). The

States expert also testified that it would have been impossible to accelerate to

3,700 RPMs and shift the car from park into reverse due to the brake limiter (VI

R.R. at 134).

B. Defenses Evidence at Guilt-Innocence

Defense counsel presented witnesses to depict a version of events in which

the applicant was being physically abused by Robins and accidentally struck him

with her car in a desperate attempt to escape his violence. Kevin Donaldson

testified that the calendar year before the applicant killed Robins he witnessed

Robins strike the applicant with his hand during a drunken rage (VII R.R. at 73-

76). Frank Reohas testified that, on the evening the applicant killed Robins, he

witnessed them arguing about a job offer the applicant received that evening from

a man she met at a bar (VII R.R. at 97). Houston Police Department officer

Melissa Holbrook testified that hours after killing Robins the applicant pointed to

several discreet places on her body where she allegedly suffered injuries after

being struck by Robins (VII R.R. at 112). Randall Dodd (Dodd), an expert in

accident reconstruction, testified regarding his opinion that Robins death was an

accident stating that he believed the applicant took her foot off the accelerator prior

14

to striking the complainant and therefore lacked the intent to kill (VII R.R. at 170).

In rendering this opinion, Dodd acknowledged the following: the applicants car

was probably accelerated to 3,700 RPMs (VII R.R. at 168); he did not disagree

with the States expert that the car physically could not be shifted from park into

reverse at 3,700 RPMs (VII R.R. at 168); and, the applicant drove at an angle that

might have caused her to hit a building had she been in reverse (VII R.R. at 210).

C. The Applicants Testimony

The applicant testified at guilt-innocence against the advice of counsel (VIII

R.R. at 4). On direct examination, the applicant characterized Robins as very

angry because she had been talking about a job with a man at the bar they had

visited (VIII R.R. at 22). The applicant begg[ed] him to stop hitting me while in

the car and indicated that the physical abuse was so bad that she was concerned

that Robins would cause a car accident (VIII R.R. at 24-25). When Robins got out

of the applicants car in an alley he was very, very upset and threw a glass at the

applicants windshield (VIII R.R. at 27-28). Contrary to her written statement, the

applicant testified that she intended to accelerate her car forward, not backward:

15

Q: (By Mr. Catlett) When he threw the glass at your

automobile whats the next action that you took?

A: I turned my head at which point I thought I saw his

blurred figure in flight towards the car door.

Q: Why when you saw when you saw this impression

what action did you take?

A: At that point he was I perceived that he was seconds

away from grabbing the car door handle or coming

around in front of the car open car door so I looked at

him what I thought was him and I thought I have just I

accelerated the car to make the car door slam so I could

lock the doors.

Q: Accelerated the car after he threw the glass at your

windshield. Why did you do that?

A: I accelerated the car to make the car door slam.

Q: Why did you want it to slam?

A: So I could lock the doors? So I could prevent him

from attacking me some more.

Q: That resulted in your hitting the wall?

A: Yes. Evidently, yes. Yes.

Q: What did you do after your car hit the door?

A: I backed up the car and I backed up the car a ways

see. After I got the car door slammed then I was going to

back up after the parking lot after he was clear of the car

and the doors were locked then I intended to back up - -

16

(VIII R.R. at 30-31). The applicant testified that, when she realized she struck

Robins with the car, I couldnt believe [it] and told him that it was an accident

and not intentional (VIII R.R. at 32).

On cross examination the applicant acknowledged that she put the car [i]n

drive on purpose in order to slam the door, but did not see Robins in front of the

car (VIII R.R. at 90). The applicant did not dispute testimony that she accelerated

her car to over 3,000 RPMs and testified that she did not expect Robins to use

deadly force against her if he returned to the car (VIII R.R. at 91-93). The

applicant maintained that she acted in self-defense: If he had come back in the car

he would have hurt me very, very badly. He had done it before (VIII R.R. at 92).

D. Defense Counsels Closing Argument

Defense counsel stressed that the incident was an accident and that the

applicant lacked the requisite mens rea to be found guilty beyond a reasonable

doubt of any offense (VIII R.R. at 133, 157). In particular he asked the jury to

focus on defense expert Dodds opinion that the applicant took her foot off the

accelerator:

But she took her foot off the gas. We know that by the

physical evidence. And thats the most important piece

of physical evidence in this case. Because it tells you

you dont have time to think in .43 seconds. She cant sit

there and plot out Im going to kill this guy, Im going to

run him into the wall but Im going to make it look like I

didnt mean it so Im going to take my foot off the gas.

17

.43 seconds, her response to that car going towards the

wall was to take her foot off the gas. That tells you

conclusively she didnt want to go in that direction. That

was not her intent.

(VIII R.R. at 150).

Counsel continued with this argument, stating that because of the stressful

situation the applicant accidentally put her car in neutral rather than park when

she stopped in the alley and then compounded the problem by shifting the car one

click down to drive when she thought she was placing the car in reverse (VIII

R.R. at 151). Drawing on Robins violent nature, defense counsel also made clear

that the accident involved self-defense:

But I think the evidence here shows and this whole

thing about was she being assaulted or not and all that, I

mean this man was thrown out of her house twice; once

off a balcony because he was over there screaming and

cursing.

. . .

Now, was she trying to keep him in the car or was she

trying to get him out. Just like they had to try and get

him out of that apartment six months earlier. He was

drunk, he had been drinking for hours. . . . Hes arguing

with her, they get in the car hes arguing. Hes harassing

her, shes trying to get him out. And an unfortunate

accident occurred.

(VIII R.R. at 156-57).

18

E. Jury Charge and Deliberations

The jury charge contained instructions for murder, manslaughter, and

criminally negligent homicide and the applicable mens rea for each offense (C.R.

at 122-25). A self-defense instruction was included specific to the murder

allegation (C.R. at 126-27).

Regarding the presumption of innocence and the burden of proof the jury

was instructed as follows:

The prosecution has the burden of proving the

defendant guilty and it must do so by proving each and

every element of the offense charged beyond a

reasonable doubt and if it fails to do so, you must acquit

the defendant.

. . .

In the event you have a reasonable doubt as to the

defendants guilt after considering all the evidence before

you, and these instructions, you will acquit her and by

your verdict say Not Guilty.

(C.R. at 130).

During its deliberations, the jury requested to review certain evidence

including the applicants written statement (C.R. at 136). The jury returned a

verdict of manslaughter (C.R. at 166).

19

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

Okonkwo v. State, 398 S.W.3d 689 (Tex. Crim. App. 2013), affects analysis

of the instant application in four distinct regards. Each stands for the proposition

that the applicants claim for habeas corpus relief should be denied.

First, the law is unsettled regarding whether a mistake of fact instruction is

always necessary in order to give effect to the statutory defense. At the time of

trial jurisprudence regarding the necessity of requesting a mistake of fact

instruction was guided by Bruno v. State, 845 S.W.2d 910 (Tex. Crim. App. 1993)

(plurality opinion). Bruno is a fractured opinion and appellate courts have

struggled to determine whether it is a plurality opinion lacking in precedent or a

majority opinion holding precedential value. In Okonkwo, this Court determined

that Bruno is a plurality opinion. Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 695 n.5. Underscoring

the unsettled legal landscape, Okonkwo also makes clear that the issue of whether a

mistake of fact instruction can be effectively subsumed in a jury charge absent a

specific instruction is unresolved. Id. at 695-96. Pursuant to Okonkwo, defense

counsel did not render deficient performance for failure to request a mistake of fact

jury instruction when the law is unsettled.

Second, the applicants claim that defense counsel rendered deficient

performance is premised upon an unpersuasive affidavit from defense counsel in

which he claims that his failure to request a mistake of fact jury instruction was

20

inadvertent rather than strategic. In Okonkwo, this Court considered a similar

defense counsel affidavit and concluded that defense counsel did not render

deficient performance when the defendants mistake could have been reasonable or

unreasonable. Id. at 696. This Court concluded that because a mistake of fact

instruction would have limited the jury to only consider a reasonable mistake as

a defense, a mistake of fact instruction would have been problematic because it

would have decreased the States burden of proof. Id. The applicants mistakes in

the instant case could also have been viewed by a juror as unreasonable. Pursuant

to Okonkwo, defense counsel rendered constitutionally reasonable performance

because a mistake of fact jury instruction would have lowered the States burden of

proof and been counterproductive.

Third, the applicant fails to demonstrate prejudice from defense counsels

failure to request a mistake of fact instruction because it is a reasonable deduction

from the record that the jury followed the direction of the charge to consider all

the evidence before you and gave effect to the applicants mistake of fact by

acquitting her of murder. Moreover, the Okonkwo concurrence determined that the

appellant did not demonstrate prejudice resulting from defense counsels failure to

request a mistake of fact instruction when the jury obviously rejected appellants

claim of an honest or good-faith mistake by finding him guilty. Id. at 702

(Cochran, J., concurring). Similarly, the applicant fails to demonstrate prejudice

21

when the jury considered and rejected her mistake of fact defense and found her

guilty of manslaughter.

Fourth, the State advances the following test to determine whether a defense

counsel must request a mistake of fact instruction: does the absence of a mistake of

fact instruction effectively prevent the jury from giving effect to a mistake of fact

defense that, if believed, would negate the mens rea and acquit the defendant?

This test is put forward in order to resolve the question left unresolved by

Okonkwo whether a mistake of fact defense can be subsumed in a jury charge

absent a specific instruction and is based upon this Courts jurisprudence in

Louis v. State, 393 S.W.3d 246, 254 (Tex. Crim. App. 2012). Applying this test to

the instant application it becomes clear that the absence of a mistake of fact jury

instruction did not effectively prevent the applicant from presenting, and the jury

considering, her mistake of fact defense.

22

ARGUMENT

The applicant asserts that defense counsel was ineffective for failing to

request a jury instruction on the statutory defense of mistake of fact as set forth in

TEX. PENAL CODE 8.02:

(a) It is a defense to prosecution that the actor through

mistake formed a reasonable belief about a matter of fact

if his mistaken belief negated the kind of culpability

required for commission of the offense.

(b) Although an actor's mistake of fact may constitute a

defense to the offense charged, he may nevertheless be

convicted of any lesser included offense of which he

would be guilty if the fact were as he believed.

An examination of the record and the law reveals that the applicants claim

is a quintessential Strickland double failure in that the applicant fails to

demonstrate unreasonable performance or prejudice. Strickland v. Washington,

466 U.S. 668, 700 (1984).

1

Accordingly, the applicants claim for relief should be

denied.

1

The Court has asked the parties to address whether Okonkwo v. State, 398 S.W.3d 689

(Tex. Crim. App. 2013), affects the analysis of the applicants claims. Ex parte Levine, No. WR-

79302-01, 2014 WL 792080, at *1 (Tex. Crim. App. Feb. 26 2014) (per curiam) (order, not

designated for publication). The applicant also asserts a claim of ineffective assistance of counsel

for failure to object to a self-defense instruction in the jury charge. Applicants Writ at 7.

Okonkwo is only tangentially related to the applicants self-defense instruction claim insofar as it

concerns the proposition of law that a defense counsels affidavit responsive to an allegation of

ineffective assistance of counsel is subject to an objective review in the context of the entire trial

record. Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 693. As a result, the States brief solely focuses on the

applicants claim of alleged ineffective assistance for failure to request a mistake of fact jury

instruction. The State reasserts that the applicants claim of ineffective assistance for failure to

23

I.

DEFENSE COUNSEL DID NOT RENDER DEFICIENT PERFORMANCE

FOR FAILURE TO REQUEST A MISTAKE OF FACT JURY

INSTRUCTION WHEN THE LAW IS UNSETTLED REGARDING

WHETHER THE INSTRUCTION IS ALWAYS NECESSARY IN ORDER

TO GIVE EFFECT TO THE STATUTORY DEFENSE

The applicants claim that defense counsel was deficient for failing to

request a mistake of fact jury instruction conflates two distinct issues: factual

sufficiency for the instruction with prevailing professional norms to make the

request. See Strickland, 466 U.S. at 688 (The proper measure of attorney

performance remains simply reasonableness under prevailing professional

norms.). Based on her written statement and trial testimony, the applicant avers

that she would have been entitled to a mistake of fact jury instruction. Applicants

Brief in Support of Writ at 11-12. In contrast to Okonkwo, the State acknowledges

that this is correct. Cf. Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 695 (the State contends that

appellant would not have been entitled to a mistake of fact instruction because the

instruction was unnecessary.). However, this does not support the applicants

contention, and the habeas courts conclusion, that defense counsels

representation was deficient because it is necessary to request the instruction in

order to give effect to the defense. Applicants Brief in Support of Writ at 12;

Finding of Fact No. 14. Simply put, the law regarding the necessity of requesting

object to the self-defense instruction is meritless and refers the Court to its Original Answer for

discussion and analysis of that claim. States Original Answer at 18-21.

24

a mistake of fact instruction in all circumstances was unsettled at the time of trial

and remains so today after this Court elected not to resolve the matter in Okonkwo.

A. Bruno v. State Creates an Unsettled Legal Environment

At the time of the applicants trial, jurisprudence regarding the necessity of a

mistake of fact jury instruction was guided by this Courts opinion in Bruno v.

State, 845 S.W.2d 910 (Tex. Crim. App. 1993) (plurality opinion).

2

In Bruno the

defendant was convicted of unauthorized use of a motor vehicle. Id. at 911. His

defense at trial was mistake of fact; he asserted that he thought he had the

complainants permission to use the car. Id. The charge included instructions on

mistake of fact and that the jury could only convict the defendant if they believed

beyond a reasonable doubt that he intentionally and knowingly operated the motor

vehicle without the complainants consent. Id. The issue before this Court was the

appellants contention that the trial court should have additionally instructed the

jury that the State was required to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that he knew

he did not have the complainants permission to drive the car. Id.

2

Prior to Bruno, the closest this Court came to exploring the issue appears to be a pre-

Penal Code case Barbar v. State, 167 Tex. Crim. 48 (1958). In Barbar the defendant was

convicted in a court trial of possession of barbiturates. Id. at 49. The defendant testified that she

was in possession of tablets and capsules but did not know that they were barbiturates. Id. at 50.

This Court determined that under the undisputed evidence the defendant brought herself within

the defense of mistake of fact. Id. In dicta, this Court then noted that the defendant presented a

mistake of fact defense without the aid of a jury instruction: We are not unmindful that the trial

herein was before the court and appellant is cast in the position she would have been in had her

defense been submitted to and rejected by a jury. Id. at 51.

25

In this Courts lead opinion in Bruno, Judge White, joined by Judges

McCormick and Campbell, determined that the charge properly placed the burden

of proof on the State. Id. at 912. However, this opinion also concluded that such

analysis misses the real question presented by this case, which is whether the

mistake of fact instruction needed to be given in the first place. Id. The mistake

of fact instruction was unnecessary since [o]nly one of the incompatible stories

could be believed. Id. at 913. The Court explained, The jury heard both stories.

As they would have necessarily been required to disbelieve appellants story before

they could find sufficient evidence to convict, the instruction need not be given in

the instant case. Id.

In a two-sentence opinion, Judge Baird, joined by Judges Miller and Meyers,

concurred believing the mistake of fact instructions was unnecessary in the instant

case. Id. (Baird, J., concurring).

3

However, Judge Baird differed from the lead

opinion in its interpretation of Gardner v. State, 780 S.W.2d 259, 262-63 (Tex.

Crim. App. 1989), an unauthorized use of a motor vehicle case concerning a

mistake of fact defense and jury instruction in which the defendant alleged he had

consent to use the automobile from a third party who he believed had the

3

BAIRD, J. concurs, believing the mistake of fact instructions was unnecessary in the

instant case. However, I do not believe the defense of mistake of fact should be limited to third

party cases.

26

permission of the actual owner to use the car. Bruno, 845 S.W.2d at 913. Judges

Clinton, Overstreet, and Maloney concurred in the result. Id.

Simply put, Bruno has bred confusion among appellate courts with Judge

Bairds concurring opinion exacerbating the problem. The first sentence of Judge

Bairds concurrence could be interpreted to indicate that six members of this Court

agreed that a mistake of fact instruction is unnecessary when only one of two

incompatible stories could be believed, making the opinion binding for that point

of law. See Sands v. State, 64 S.W.3d 488, 497 (Tex. App. Texarkana 2001, no

pet.) (Cornelius, C.J., concurring) (Bruno has precedential value because six judges

held that it was not necessary to give a mistake of fact instruction in that case); see

also Thompson v. State, 93 S.W.3d 16, 26 (Tex. Crim. App. 2001) (examining the

plurality opinion in Wesbrook v. State, 29 S.W.3d 103 (Tex. Crim. App. 2000)

(plurality opinion), and concluding that seven judges in Wesbrook embraced a

particular point of law and therefore Wesbrook was authority for that point of law).

In Brunos confusing wake, Judge Walker of the Ninth Court of Appeals indicated

the present state of the law regarding the propriety of submitting the defensive

issue of mistake of fact is entirely unclear to me. Traylor v. State, 43 S.W.3d

725, 731 (Tex. App. Beaumont 2001, no. pet.) (Walker, J. concurring).

4

Indeed,

4

To underscore this point Judge Walker attached as an exhibit to his concurrence an

unpublished dissenting opinion of this Court authored by Judge Johnson and joined by Judges

Meyers and Price referencing the decision of the majority to reverse the Ninth Court of Appeals

27

the First, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Ninth, and Fourteenth districts sharply split on

whether Bruno is a plurality or majority opinion and whether or not the Courts

determination that the mistake of fact instruction was unnecessary is dicta or

controlling.

5

decision Grant v. State, No. 09-94-181-CR, 1998 WL 809413, at *2 (Tex. App.- Beaumont Nov.

18, 1998). Traylor, 43 S.W.3d at 732-34. The Ninth Court of Appeals found that the trial court

erred in denying the appellants request for a mistake of fact jury instruction in an evading arrest

trial, but the Court of Criminal Appeals reversed concluding the instruction was encompassed

in the trial courts jury charge which instructed the jury to convict only if it found beyond a

reasonable doubt that appellant knew the officer in question was a police officer. Id. at 732.

This reasoning is akin to that advanced by the State to support its argument that the applicants

mistake of fact defense was effectively subsumed in the jury charge. See infra at 48-50.

5

Compare Sands, 64 S.W.3d at 497 (Cornelius, C.J., concurring) (Bruno holds

precedential value); Turner v. State, No. 04-03-00436-CR, 2004 WL 1881748, at *7 (Tex.

App. San Antonio Aug. 25, 2004, no pet.) (mem. op., not designated for publication) (citing

Bruno as authority for holding that an attorney was not ineffective for failing to request a mistake

of fact instruction when the jury necessarily had to consider defendants mistake of fact evidence

before being able to find defendant guilty beyond a reasonable doubt); Guerrero v. State, No. 01-

11-00091-CR, 2012 WL 1564670, at *4 (Tex. App. Houston [1st Dist.] May 3, 2012, no pet.)

(mem. op., not designated for publication) (same); Barajas v. State, No. 05-93-00042-CR, 1995

WL 519352, at *3 (Tex. App. Dallas Aug. 28, 1995, no. pet.) (mem. op., not designated for

publication) (same); Traylor, 43 S.W.3d at 730-31 (citing Bruno as precedent to support holding

that trial court did not err in refusing request for mistake of fact jury instruction when the jury

could not have convicted defendant if they believed his story); Hopson v. State, No. 14-08-

00735-CR, 2009 WL 1124389, at *2-4 (Tex. App. Houston [14

th

Dist.] Apr. 28, 2009, no. pet.)

(mem. op., not designated for publication) (citing Bruno as authority for the proposition that the

Texas Court of Appeals indicated that a trial court is not always required to submit an

unnecessary mistake-of-fact instruction if the defense is adequately covered by the charge as

given.), with Sands, 64 S.W.3d at 494 (holding Bruno is a plurality opinion, not binding

precedent, and its language regarding the mistake of fact instruction as unnecessary is dicta);

Okonkwo v. State, 357 S.W.3d 815, 820 (Tex. App. Houston [14

th

Dist.] 2011, pet. granted)

(holding that Bruno was a plurality opinion and the language upon which the State relied is dicta)

revd by Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 696-97.

28

B. Okonkwo v. State Recognizes as Unresolved the Necessity of

Requesting a Mistake of Fact Jury Instruction to Give Effect to

the Defense When the State Must Prove the Mens Rea Beyond a

Reasonable Doubt

In Okonkwo, this Court determined that a defense attorney rendered

constitutionally reasonable performance when he failed to request a mistake of fact

jury instruction in a forgery trial even though it was the defendants only defense.

Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 696-97; see also Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 699-703

(Cochran, J., concurring). To reach this holding this Court examined Brunos

scope and reinforced that the necessity of requesting a mistake of fact jury

instruction in order to give effect to the defense the issue at the core of the

applicants claim

6

is unresolved.

To support its position in Okonkwo that defense counsels performance was

constitutionally reasonable, the State argued that, because an element of its case

required proof that the defendant acted with intent to defraud or harm another, it

necessarily had to prove that he knew the bills were forged, which was the same

fact about which appellant claimed to have been mistaken. Id. at 695. In

language suggestive of Brunos reasoning that [o]nly one of the incompatible

stories could be believed, this Court determined that the State correctly observes

6

Her mistaken beliefs negated that she recklessly caused his death. Had the jury so

believed or had a reasonable doubt, it would have acquitted her or, at most, convicted her of

negligent homicide. Counsel performed deficiently in failing to request an instruction on

mistake of fact. Applicants Writ at 6a.

29

that proof of the culpable mental state necessarily proves lack of mistake regarding

the authenticity of the bills. Id. at 695.

Although acknowledging that the States reasoning was correct, this Court

then specifically chose not to resolve the States second ground for review: Can it

ever be deficient performance not to request a mistake-of-fact instruction when the

offense requires the State to prove knowledge beyond a reasonable doubt?

Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 693.

In other words, the State suggests that, because the

substance of the mistake-of-fact defense was subsumed

by the charge and merely negated an element the State

was required to prove, a mistake-of-fact instruction

would not have been required and served no purpose. By

contrast, appellant contends that, because the mistake-of-

fact instruction is codified, it must be given if it negates a

defendants culpable mental state, is raised by the

evidence, and is requested by a party. This Court has not

yet resolved this dispute, and we need not do so here in

the context of a complaint of ineffective assistance of

counsel because, under either of the scenarios promoted

by the State and appellant, appellant has not shown that

counsel was objectively unreasonable in failing to request

an instruction on mistake of fact.

Id. at 695-96 (emphasis added) (citations and footnotes omitted).

In deciding not to resolve the States second ground for review, this Court

examined Bruno in a footnote observing, A plurality of this Court determined that

a mistake-of-fact instruction was unnecessary because the jury could believe

30

either Bruno or the owner, but not both. Id. at 695 n. 5 citing Bruno, 845 S.W.2d

at 911.

Three points are particularly relevant from this footnote. First, this Court

clarified that Bruno is a plurality opinion. Second, this Court did not indicate that

Brunos reasoning was dicta. Third, this Court did not adopt the Fourteenth Court

of Appeals reasoning that Brunos reach was limited to unauthorized use of motor

vehicle cases. Cf. Okonkwo, 357 S.W.3d at 820 (The Bruno plurality merely held

that an instruction may not be required in a narrow subset of theft cases.).

31

C. Defense Counsel Did Not Render Deficient Performance in an

Unsettled Legal Environment

At a threshold level, the instant application is resolved by the Court of

Criminal Appeals decision in Okonkwo to leave undisturbed the dispute

regarding the necessity of requesting a mistake of fact jury instruction in order to

give effect to the defense. Because Bruno was a plurality opinion, and therefore

not precedent, defense counsel was unquestionably operating in an unsettled legal

environment. Indeed, this Court suggested that it was not certain Okonkwo would

have been entitled to a mistake of fact instruction under the facts of the case.

Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 697 (Even if the law permitted counsel to obtain an

instruction on mistake of fact under these circumstances) (emphasis added).

To establish a claim of ineffective assistance of counsel, the applicant must

show that (1) defense counsels performance was deficient, and (2) she suffered

resulting prejudice, recognized as a reasonable probability that, but for counsels

errors, the result of trial would have been different. Strickland, 466 U.S. at 687-94.

Jurisprudence is well established that an attorney cannot commit deficient

performance when the law upon which a post-conviction claim rests is unsettled.

Ex parte Welch, 981 S.W.2d 183, 184 (Tex. Crim. App. 1998) ([W]e will not find

counsel ineffective where the claimed error is based upon unsettled law.).

32

The applicant invites this Court to overlook precedent and reject the

Supreme Courts direction that the proper measure to evaluate attorney

performance is simply reasonableness under prevailing professional norms.

Strickland, 466 U.S. at 688. Given that prevailing professional norms did not exist

at the time of trial, this Court should decline the applicants invitation and reject

her claim for relief. See Ex parte Smith, 296 S.W.3d 78, 81 (Tex. Crim. App.

2009) (counsel rendered constitutionally reasonable performance in advising

defendant to plead guilty to a felon in possession of a weapon charge when the law

was unclear at the time of the plea as to whether or not the defendants open felony

deferred adjudication was considered a conviction); see also Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d

at 699-700 (Cochran, J., concurring) (defense counsels failure to request a mistake

of fact instruction was constitutionally reasonable when the law regarding the

applicability of with knowledge that the writing was forged as a culpable mental

state element of forgery was unsettled).

II.

DEFENSE COUNSELS ASSERTION THAT HIS FAILURE TO REQUEST

A MISTAKE OF FACT INSTRUCTION WAS INADVERTENT RATHER

THAN STRATEGIC DOES NOT DEMONSTRATE DEFICIENT

PERFORMANCE

The applicants claim of deficient performance is premised on the statement

in defense counsels affidavit that his failure to request a mistake of fact instruction

33

was inadvertent rather than strategic. Applicants Writ Exhibit No. 2, Affidavit of

Don Catlett. The habeas court determined defense counsels affidavit to be

credible and concluded that his failure to request an instruction on mistake of fact

was not strategic. Finding of Fact No. 7, 15. However, these findings are not

supported by the record, and this Court should exercise its authority to make

contrary findings and conclusions. Through the lens of Okonkwo it is clear that the

habeas court placed too much emphasis on defense counsels subjective critique of

his performance rather than conducting a more probing inquiry of the record.

A. Defense Counsels Affidavit is Unpersuasive

Drafted more than twelve years after trial, and absent reference that he

reviewed his file or the appellate record, defense counsels affidavit is riddled with

significant inaccuracies likely attributable to faded memories caused by the passage

of time. These errors render his affidavit unpersuasive and insufficient to support

the habeas courts deficient performance finding.

With regard to mistake of fact, defense counsel states the following

regarding his representation:

The indictment alleged that Levine intentionally

and knowingly caused the death of Bill Robins by

striking him with a motor vehicle. She told the police

and testified at trial that she thought she was shifting

from park into reverse when, in fact, she was shifting

34

from neutral into drive; that she drove forward instead of

backward; and that she did not intend to hit Robins.

. . . I argued that Robins died as a result of an

accident that occurred when Levine shifted from neutral

into drive in the belief that she was shifting from park

into reverse.

I never considered raising the defense of mistake

of fact contained in section 8.02(a) of the Penal Code. If

I had, I would have requested an instruction on this

statutory defense. Had the court given the instruction, I

would have argued that the jury should acquit Levine

because she reasonably believed that her car was in

reverse when she accelerated. Had the court refused the

instruction, I would have objected in order to preserve

the issue for appellate review. My failure to request an

instruction on mistake of fact was inadvertent rather than

strategic.

Applicants Writ Exhibit No. 2 (emphasis added).

Okonkwo requires that defense counsels affidavit be reviewed from an

objective standard in the context of the entire trial record. Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d

at 693-94. Three glaring inaccuracies are immediately apparent from this objective

review.

First, the applicant did not testify at trial that she thought she was shifting

from park into reverse. Indeed, her testimony was profoundly different. Perhaps

in response to the States evidence that it would have been impossible for her to

accelerate her car to 3,700 RPMs and then shift into reverse, the applicant changed

her story and testified that she intentionally accelerated forward to make the car

doors slam shut (VI R.R. at 134) (VII R.R. at 30-31).

35

Second, defense counsels affidavit assertion he never considered the

defense of mistake of fact contained in section 8.02(a) of the Penal Code is not

supported by the record. The record reflects that defense counsel presented a

mistake of fact defense, characterized as an accident, through Dodds expert

opinion that the applicant took her foot off the accelerator. In closing argument,

defense counsel characterized Dodds testimony as the most important piece of

physical evidence in the case and made a plea for the jury to consider Dodds

opinion as it related to the mens rea: That tells you conclusively she didnt want

to go in that direction. That was not her intent. (VIII R.R. at 150-51).

Third, defense counsels affidavit contention that Had the court given the

[mistake of fact] instruction I would have argued that the jury should acquit Levine

because she reasonably believed that her car was in reverse when she accelerated

inaccurately suggests that his argument was contingent on the instruction. In fact,

absent a mistake of fact instruction, defense counsel made this very argument:

because of the stressful situation the applicant accidentally put her car in neutral

rather than park and then compounded the problem by shifting the car one click

down to drive when she thought she was placing the car in reverse (VIII R.R. at

151)

This Court will generally defer to the trial courts findings of fact that are

supported by the record. Ex parte Reed, 271 S.W.3d 698, 727 (Tex. Crim. App.

36

2008). This same level of deference is also afforded a habeas judges ruling on a

mixed question of law and fact, if the resolution of those questions turns on an

evaluation of credibility and demeanor. Guzman v. State, 955 S.W.2d 85, 89 (Tex.

Crim. App. 1997). However, this Court will afford no deference to findings and

conclusions that are not supported by the record. Ex parte Reed, 271 S.W.3d at

727. Simply put, the habeas courts findings merit no deference.

The multiple errors in defense counsels affidavit are not minor.

7

To the

contrary, in the space of a little more than one double-spaced page, defense counsel

inaccurately depicts the applicants testimony as well as his own trial strategy and

jury argument. Accordingly, this Court should exercise its authority to make a

contrary finding regarding the persuasiveness of defense counsels affidavit and

find that the applicant has not demonstrated deficient performance. See Ex parte

Weinstein, 421 S.W.3d 656 (Tex. Crim. App. 2014) (holding the habeas courts

materiality determination was unsupported by the record and entering a contrary

finding).

B. Defense Counsels Affidavit is Insufficient to Support the Habeas

Courts Deficient Performance Finding

In Okonkwo this Court considered a defense counsels affidavit that was

strikingly similar to that filed in support of the instant application and concluded

7

Defense counsels affidavit also inaccurately states the record regarding his self-defense

strategy. See States Original Answer at 18-20.

37

the affidavit was not determinative of deficient performance. Adopting this same

approach, the State respectfully submits that this Court should reach a similar

conclusion in deciding the merits of the instant application.

Okonkwos defense attorney indicated in an affidavit that his failure to

request a mistake of fact jury instruction was inadvertent rather than strategic:

At the close of the evidence in this matter, I did not

request that the trial court instruct jurors on the statutory

defense of mistake of fact as set out in Section 8.02(a) of

the Texas Penal Code. My failure to do so was not the

result of trial strategy or tactic. At the time for

formulating the jury charge, it did not occur to me to

request a charge on the statutory defense of mistake of

fact, even though the evidence adduced at trial was

clearly more than a scintilla of evidence tending to raise

the statutory defense of mistake of fact.

Okonkwo, 357 S.W.3d at 818, revd, 398 S.W.3d 689.

Notwithstanding the affidavit, this Court held that defense counsels

inadvertence was not objectively unreasonable. Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 696. At

the heart of the Courts conclusion was a determination that the instruction might

actually have harmed the appellant because under the statutory defense of mistake

of fact the mistake must be reasonable. Id., citing TEX. PENAL CODE 8.02 (It

is a defense to prosecution that the actor through mistake formed a reasonable

belief about a matter of fact). The evidence at trial suggested that the mistake of

fact could have been reasonable or unreasonable. Id. Therefore, a mistake of fact

jury instruction would have been problematic for appellant because the instruction

38

would have decreased the States burden of proof by permitting the jury to convict

him if it concluded that his mistake was unreasonable, even if it found that mistake

to be honest. Id.; see also Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 702 (Cochran, J., concurring)

(Appellants attorney urged the easier defense an honest mistake rather than

the more onerous one an honest and reasonable mistake) (emphasis in original).

Professors Dix and Schmolesky echo this Courts Okonkwo holding to note that

there is reason to hesitate before making a request for a mistake of fact

instruction as it lowers the proof required for conviction; for this reason they

characterize the decision to request the jury instruction as dubious. 43 George

E. Dix & John M. Schmolesky, Texas Practice: Criminal Practice and Procedure

43.36 (2013).

In the instant application, the habeas court concluded that defense counsels

incantation of no strategy satisfied Stricklands deficient performance prong;

Okonkwo necessitates a different determination. As in Okonkwo, by not requesting

a mistake of fact jury instruction, defense counsel permitted the jury to consider

the applicants mistakes as either reasonable or unreasonable. Indeed, the mistakes

could be interpreted in either light.

The evidence defense counsel presented at trial suggested that the applicant

committed a mistake that a juror may have found reasonable: accelerating her car

to 3,700 RPMs and accidentally shifting from neutral into drive when she thought

39

she was shifting from park into drive. However, a juror may also have found this

mistake to be unreasonable in light of evidence that it was impossible to accelerate

the car to over 3,000 RPMs and shift into reverse due to the brake limiter.

Testifying against defense counsels advice, the applicant offered a different

mistake that a juror may have found reasonable: she thought that Robins was

beside the car, not in front. Again, a juror may also have found this mistake to be

unreasonable in light of evidence that Robins was actually near a wall when he was

struck. Importantly, defense counsel made no characterization as to whether the

applicants mistake was reasonable or unreasonable thereby allowing the jury to

consider either possibility (VIII R.R. 149-58).

In short, defense counsels affidavit does not establish deficient performance

because the absence of a mistake of fact instruction actually benefitted the

applicant. Had the instruction been requested and given it would have limited the

jury to consider only reasonable mistakes made by an ordinary prudent person

under the same circumstances. Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 702 (Cochran, J.,

concurring) citing Mays v. State, 318 S.W.3d 368, 383 (Tex. Crim. App. 2010).

Given the unreasonableness of the applicants mistakes this may have caused the

jury to convict based on a lessened burden of proof. Under these circumstances,

defense counsel did not render constitutionally deficient performance and the

applicants claim for relief should be denied. Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 686; but cf.

40

Vasquez v. State, 830 S.W.2d 948, 951 (Tex. Crim. App. 1992) (per curiam)

(defense attorney rendered ineffective assistance for failure to request a necessity

instruction when the defendant had nothing to lose by requesting a defensive

instruction) (emphasis added).

41

III.

THE APPLICANT FAILS TO DEMONSTRATE STRI CKLAND

PREJUDICE BECAUSE THE JURY CONSIDERED HER MISTAKES OF

FACT

The record suggests that the jury considered the applicants mistake of fact

defense, and did so to her benefit. Jurors were directed to consider all the

evidence, instructed that the State must prove the mens rea beyond a reasonable

doubt, and required to acquit the applicant if the State failed to meet its burden of

proof (C.R. at 122-25). Importantly, the jury specifically requested to see the

applicants statement in which she indicated that her intent was to back out and

away from Robins (C.R. at 136). The jury acquitted the applicant of murder and

convicted her of manslaughter (C.R. at 166).

Notwithstanding the clear language in the charge and the jurys request to

review the applicants statement detailing her mistake, the habeas court concluded:

a properly instructed jury . . . probably would have

concluded that she did not recklessly cause his death and

either acquitted her or convicted her of negligent

homicide. Thus, had the jury been instructed on the

defense of mistake of fact, there is a reasonable

probability that the outcome of the trial would have been

different.

Finding of Fact No. 26. This finding is bereft of citation to legal authority or

support from the record. Indeed, the finding is utter speculation. Cf. Estrada v.

State, 313 S.W.3d 274, 285-88 (Tex. Crim. App. 2010) (defendant demonstrated

42

false evidence prejudice from a jury note inquiring about testimony ultimately

found to be false). By contrast, applying the reasoning of the Bruno plurality and

the Okonkwo concurrence to the record of the case, it is clear that the applicant did

not suffer Strickland prejudice.

In Okonkwo the concurrence determined that the appellant did not satisfy

Stricklands prejudice prong. Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 702 (Cochran, J.,

concurring). In reaching this determination, it appears that Brunos [o]nly one of

the incompatible stories could be believed reasoning served as a point of

reference:

The jury obviously rejected appellants claim of an

honest or good-faith mistake by finding him guilty. If the

jury rejected that claim, then it inexorably follows that it

would have rejected the two-pronged claim that appellant

made an honest mistake and that his mistake was a

reasonable one that an ordinary prudent person in his

position would have likely made.

Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 702 (Cochran, J., concurring).

As in Bruno and Okonkwo, the jurors in the instant case were presented two

incompatible stories regarding the applicants intent. A reasonable deduction from

the record is the possibility that the jury considered and believed that the applicant

did not intend to accelerate forward and, in keeping with the jury charge, acquitted

the applicant of murder because the State failed to prove the mens rea beyond a

reasonable doubt. However, considering the same mistake, the jury rejected the

43

applicants claim that she was not reckless in light of her acknowledgement that

she accelerated to over 3,000 RPMs and evidence that Robins was near a wall

when he was struck. Indeed, Texas case law is replete with examples of juries

coming to similar conclusions. See, e.g., Griffith v. State, 315 S.W.3d 648, 652

(Tex. App. Eastland 2010, pet. refd) (evidence sufficient to support

manslaughter conviction when defendant struck complainant with a van and there

was ample evidence the defendant should have been aware of the complainants

location); Cooks v. State, 5 S.W.3d 292, 295-97 (Tex. App. Houston [14th Dist]

1999, no pet.) (evidence sufficient to support manslaughter conviction when

defendant struck complainant while driving twice the posted speed limit).

The inability of the applicant to demonstrate prejudice is further underscored

by this Courts decision to refuse discretionary review in the post-Okonkwo case

Reyes v. State, No. 10-12-00205-CR, S.W.3d , 2013 WL 5872738, at *7-9

(Tex. App. Waco Oct. 31, 2013, pet. refd). In Reyes, the defendant was

convicted of burglary of a habitation. Id. at *1. His defense was mistake of fact;

he acknowledged pawning property for his former girlfriend but alleged that he did

not know the property was stolen. Id. at *9. The trial court denied the defendants

request for a mistake of fact jury instruction and the Waco court of appeals

determined that this was error. Id. at *7-8. However, the appellate court cited to

Bruno as precedent that the defendant did not suffer some harm from the error:

44

Thus, a mistake-of-fact instruction was not essential because the fact finder would

necessarily have had to reject Reyess defense to convict Reyes of the elements of

the crime as a principal. Id. at *8-9, citing Bruno, 845 S.W.2d at 913 (plurality

opinion). In short, if Reyes did not suffer some harm because the jury would

necessarily have had to reject his defense to find him guilty, it logically follows

that the applicant in the instant case does not demonstrate prejudice because the

jury necessarily rejected her mistake in order to find that she acted recklessly and

committed manslaughter.

Simply put, the habeas courts conclusion that the applicant satisfies

Stricklands prejudice prong is unsupported by the record and not worthy of

confidence. Accordingly, the State respectfully requests that this Court exercise its

authority to make alternative findings and, consistent with Bruno, Okonkwo, and

Reyes, reject the applicants claim for relief.

45

IV.

THE JURY CHARGE DID NOT EFFECTIVELY PREVENT THE

APPLICANT FROM PRESENTING A MISTAKE OF FACT DEFENSE

In Okonkwo, this Court considered, but did not render an opinion, regarding

the States argument that a mistake of fact defense can effectively be subsumed in

a jury charge absent specific language on the statutory defense. Okonkwo, 398

S.W.3d at 695-96. The State advances this same argument, as well as a suggested

test, to demonstrate that the applicant fails to satisfy both Strickland prongs.

This Court has examined the contours of whether or not a mistake of fact

instruction is required in order for a jury to give effect to the statutory defense in

two cases involving the interrelationship between transferred intent and mistake of

fact: Thompson v. State, 236 S.W.3d 787 (Tex. Crim. App. 2007), and Louis v.

State, 393 S.W.3d 246 (Tex. Crim. App. 2012). Examining the Penal Code of

1948, the Model Penal Code, and the current Penal code, Thompson concluded that

The history of these two provisions reveals that the law of transferred intent with

respect to offenses has been entwined with the law of mistake. . . . these two

aspects of the law go hand-in-hand.

8

Thompson, 236 S.W.3d at 799. Mistake of

fact mitigates greatly the concern that a person could be penalized far beyond his

8

Okonkwo also recognized the close relationship between these two provisions of the

Penal Code and suggested that a defense attorney may per se render deficient representation if he

does not request a mistake of fact jury instruction to negate a transferred intent element.

Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 697 n. 9, citing Thompson, 236 S.W.3d at 799-800.

46

actual culpability. Id. at 790. Because of this interrelationship, Louis held a

defendant suffered some harm from the trial courts failure to charge the jury on

mistake of fact: Lack of the requested instruction effectively prevented appellant

from presenting his defense and is not harmless. Louis, 393 S.W.3d at 254

(emphasis added).

Through the lens of Louis effectively prevented reasoning, the State

suggests that this Court adopt the following test to determine whether a defense

counsel must request a mistake of fact instruction: does the absence of a mistake of

fact instruction effectively prevent the jury from giving effect to a mistake of fact

defense that, if believed, would negate the mens rea and acquit the defendant?

Applying that test to the instant application, it becomes apparent that it was

unnecessary for defense counsel to request a mistake of fact instruction for three

distinct reasons.

First, mistake of fact was subsumed by the standard jury charge. Jurors were

directed to consider all the evidence, instructed that the State must prove the

mens rea beyond a reasonable doubt, and required to acquit the applicant if the

State failed to meet its burden of proof (C.R. at 122-25). Absent the instruction,

the charge permitted the jury to negate the mens rea if it determined that the

applicant had a mistaken belief of fact regarding the gear the car was in or where

Robins was standing.

47

Judge Womacks concurring opinion in Posey v. State, 966 S.W.2d 57, 70-

71 (Tex. Crim. App. 1998) (Womack, J., concurring), supports this position.

Posey concerned whether TEX. CODE CRIM. PROC. art. 36.14 imposes a duty on

trial courts to sua sponte instruct the jury on unrequested defensive issues. Id. at

62. The majority of this Court determined that the trial court did not err in

omitting mistake of fact from the jury charge when the appellant did not request

the instruction and did not object to its absence. Id. at 59-64. Judge Womack

concluded that the trial court should have submitted an instruction on mistake of

fact but that its omission from the jury charge was harmless:

In this case the jury could give effect to the defense of

mistake of fact. The charge permitted, and even

required, the jury to find the appellant not guilty if there

was a reasonable doubt about the culpable mental state

his knowledge that he did not have consent to drive the

vehicle. The charge fully defined knowingly, and the

application paragraph required the jury to find that the

appellant acted knowingly. (The adequacy of the charge

may explain why the appellant did not request a separate

defensive issue of mistake of fact.) The appellant had no

difficulty in presenting his defense under the charge that

was submitted, by arguing to the jury that his evidence

showed he did not know the vehicle was stolen. The

State met his argument directly. The defensive issue was

squarely presented to the jury by the charge.

Id. at 70-71.

9

9

See also Sands, 64 S.W.3d at 496 (trial courts error in failing to instruct on mistake of

fact was not harmful to the defendant when the State had to prove the mens rea beyond a

reasonable doubt and therefore the jury came face-to-face with making a decision of whether

[the defendant] intentionally and knowingly possessed methamphetamine.).

48

Second, because the State did not allege transferred intent to a higher level

offense, mistake of fact was not necessary to negate the transfer. Instead, the jury

charge included the lower level offenses of manslaughter and criminally negligent

homicide and the applicable culpable mental states of both (C.R. at 122-25). The

presence of these lesser included offenses is of particular note because TEX. PENAL

CODE 8.02(b) makes clear that a defendant may be acquitted of an offense due to

mistake of fact but may nevertheless be convicted of a lesser included offense if

the facts were as the defendant believed. A reasonable deduction from the record

is that this occurred in the applicants case. See supra at 44-45.

Third, the jury charge actually facilitated the applicants mistake of fact

defense. Because it did not simultaneously impose a duplicative, and potentially

harmful, instruction regarding the reasonableness of the applicants mistakes, the

jury charge was actually superior to one that the applicant insists should have been

requested. See supra at 39-40.

In sum, a mistake of fact jury instruction was unnecessary since the defense

was unquestionably subsumed in the applicants jury charge and the applicant was

not effectively prevented from presenting her defense. Accordingly, the

applicant fails to demonstrate deficient performance or prejudice, and her claim for

relief should be denied. Strickland, 466 U.S. at 700; Okonkwo, 398 S.W.3d at 702-

03 (Cochran, J., concurring).

49

PRAYER

The applicants claim for relief is meritless. She asks that a prevailing

professional norm be recognized and retroactively applied, inaccuracies in her

attorneys affidavit be overlooked, and prejudice be assumed notwithstanding a

reasonable deduction from the record that the jury actually gave effect to her

mistake of fact defense. The habeas court embraced the applicants claim; this

Court should not.

Okonkwo makes clear that the applicant fails to demonstrate that her attorney

rendered deficient performance or that she was in any way prejudiced by his

representation. To the contrary, defense counsel and the jury charge

unquestionably made the adversarial testing process work. Accordingly, the State

prays that the Court of Criminal Appeals deny the instant application for habeas

corpus relief.

50

SIGNED this 28th day of April, 2014.

RESPECTFULLY SUBMITTED,

DEVON ANDERSON

DISTRICT ATTORNEY

HARRIS COUNTY, TEXAS

_________________________________

Joshua A. Reiss

Assistant District Attorney

Harris County District Attorney

1201 Franklin

Houston TX 77002

(713) 755-6657

(713) 755-5809 (fax)

reiss_josh@dao.hctx.net

SBOT # 24053738

51

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE AND COMPLIANCE

Service has been accomplished by sending a copy of the accompanying

instrument to the applicants counsel via U.S. mail at the following address:

Randy Schaffer

The Schaffer Firm

1301 McKinney

Suite 3100

Houston, Texas 77010

Pursuant to TEX. R. APP. P. 9.4, I certify that the instant document contains

9,101 words.

SIGNED this 28th day of April, 2014.

_________________________________

Joshua A. Reiss

Assistant District Attorney

Harris County District Attorney

1201 Franklin

Houston TX 77002

(713) 755-6657

(713) 755-5809 (fax)

reiss_josh@dao.hctx.net

SBOT # 24053738

You might also like

- State's Brief in Eddie Ray Routh AppealDocument63 pagesState's Brief in Eddie Ray Routh AppeallanashadwickNo ratings yet

- EasyKnock v. Feldman and Feldman - Motion To DismissDocument32 pagesEasyKnock v. Feldman and Feldman - Motion To DismissrichdebtNo ratings yet

- Case Nos. 14-35420 & 14-35421: Plaintiffs-AppelleesDocument858 pagesCase Nos. 14-35420 & 14-35421: Plaintiffs-AppelleesEquality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- Carla Roberson Cummings in Supreme Count of TexasDocument41 pagesCarla Roberson Cummings in Supreme Count of TexasShirley Pigott MD0% (1)

- State V Kevin Johnson - Motion To Vacate - 11-15-22Document54 pagesState V Kevin Johnson - Motion To Vacate - 11-15-22Jessica BrandNo ratings yet

- Cosby Appeal BriefDocument44 pagesCosby Appeal BriefTHROnlineNo ratings yet

- Texas Supreme Court 14-0192 Response To Petition (1) Tom CrowsonDocument37 pagesTexas Supreme Court 14-0192 Response To Petition (1) Tom CrowsonxyzdocsNo ratings yet

- 03-13-00686-CV - AG BriefDocument65 pages03-13-00686-CV - AG BriefThe Dallas Morning NewsNo ratings yet

- Pierce V WaDocument91 pagesPierce V WaFinally Home RescueNo ratings yet

- In The United States Court of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit: Plaintiffs-AppelleesDocument42 pagesIn The United States Court of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit: Plaintiffs-AppelleesKathleen PerrinNo ratings yet

- 1:14-cv-00406 #46Document218 pages1:14-cv-00406 #46Equality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- Routh New Trial RequestDocument66 pagesRouth New Trial RequestBob PriceNo ratings yet

- 1:13-cv-00482 #30Document209 pages1:13-cv-00482 #30Equality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- LWVUT - Legislative Defendants MTD 5.2.22Document39 pagesLWVUT - Legislative Defendants MTD 5.2.22Robert GehrkeNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit: K M. P, ., v. A S, ., and P 8 O P D H, .Document43 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit: K M. P, ., v. A S, ., and P 8 O P D H, .Kathleen PerrinNo ratings yet

- Texas Court of Criminal Appeals Mandamus by Paxton Special Prosecutors June 2017Document160 pagesTexas Court of Criminal Appeals Mandamus by Paxton Special Prosecutors June 2017lanashadwick100% (1)

- File Stamp Motion For Rehearing - FMDocument22 pagesFile Stamp Motion For Rehearing - FMHayden Sparks100% (1)

- Texas Supreme Court 14-0192 Petition Andrea CrowsonDocument64 pagesTexas Supreme Court 14-0192 Petition Andrea Crowsonxyzdocs100% (1)

- Memorandum of Law in Support of Defendants' Motion To DismissDocument21 pagesMemorandum of Law in Support of Defendants' Motion To DismissBasseemNo ratings yet

- 20-1230 Appellee BriefDocument68 pages20-1230 Appellee BriefRicca PrasadNo ratings yet

- Castleman Consulting vs. The Offline Assistant Appeal PaperworkDocument84 pagesCastleman Consulting vs. The Offline Assistant Appeal PaperworkTim CastlemanNo ratings yet

- Colorado Republican State Central Committee v. Anderson Cert Petition PDFA RedactedDocument45 pagesColorado Republican State Central Committee v. Anderson Cert Petition PDFA RedactedAaron ParnasNo ratings yet

- Blurred AppellateDocument73 pagesBlurred AppellateEriq Gardner0% (1)