Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Asian Development Bank-Commercialization of Microfinance - Indonesia

Uploaded by

Madalina Nicoleta AndreiOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Asian Development Bank-Commercialization of Microfinance - Indonesia

Uploaded by

Madalina Nicoleta AndreiCopyright:

Available Formats

COMMERCIALIZATION OF

MICROFINANCE

1,-51)

$tephanie Charitonenko

and Ismah Atwan

Asian Development Bank

Copyriht. Asian Development Bank 2003

All rihts reserved.

The views expressed in this book are those ot the authors and do not necessarily retlect the views and

policies ot the Asian Development Bank, or its Board ot Oovernors or the overnments they represent.

The Asian Development Bank does not uarantee the accuracy ot the data included in this publication

and accepts no responsibility tor any consequences ot their use.

Lse ot the term country" does not imply any judment by the authors or the Asian Development Bank

as to the leal or other status ot any territorial entity.

This publication is available in the Asian Development Bank's microtinance website.

http.www.adb.ormicrotinance

I$BN 9715615066

Publication $tock No. 091203

Published by the Asian Development Bank, November 2003.

FOREWORD

The microfinance industrv has evolved si,nificantlv over the past two decades. However, the outreach

of the industrv remains well below its potential in the Asia and Pacific re,ion. lf the full potential of

microfinance for povertv reduction is to be realized, it is essential to expand its outreach substantiallv. lt

is in this context that commercialization of the industrv has become a subject of in-depth studv. Althou,h

manv industrv stakeholders appear to believe firmlv that commercialization is necessarv, there is inadequate

understandin, of the complex process of movin, toward a sustainable microfinance industrv with a

massive outreach.

The Microfinance Development Strate,v of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), approved in June

2OOO, provides a framework for supportin, the development of sustainable microfinance svstems that

provide diverse, hi,h-qualitv services to traditionallv underserved low-income or poor households and

their microenterprises. ne element of this strate,v is support for development of viable microfinance

institutions that can set in motion a process of commercialization of microfinance services. As a first

step, ADB approved in November 2OOO a re,ional technical assistance project on Commercialization of

Microfinance, to improve understandin, of the process of microfinance commercialization as well as its

challen,es, implications, and prospects. The project, which was financed from the Japan Special lund,

has three components: countrv studies on microfinance commercialization, in-countrv workshops to

discuss the countrv studies and specific institutional experiences, and a re,ional workshop to discuss

each countrv studv and institutional experiences in a comparative context.

The countries chosen for studv-Ban,ladesh, lndonesia, Philippines, and Sri lanka-represent

different sta,es of development and commercialization of the microfinance industrv.

The lndonesia countrv studv was carried out bv Stephanie Charitonenko of Chemonics lnternational,

lnc. and lsmah Afwan, an independent consultant. Their report, presented here, was first presented at

the Countrv Workshop on Commercialization of Microfinance, 12-13 March 2OO3, Mulia Hotel Senavan,

Jakarta. Workshop participants provided valuable input to refine the report and improve its relevance.

This publication is one of a series of papers resultin, from the project. The series comprises four

countrv reports (on Ban,ladesh, lndonesia, Philippines, and Sri lanka, respectivelv) and a re,ional

report coverin, these countries.

lt is hoped that this publication series will contribute to a better understandin, of the issues involved

in commercialization of microfinance and lead to better approaches toward a sustainable microfinance

industrv that will provide a wide ran,e of services to low-income and poor households not onlv in the

Asia and Pacific re,ion but also in other re,ions.

NIMAL A. IRNANDO

lead Rural linance Specialist

linance and lnfrastructure Division

Re,ional and Sustainable Development Department

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are ,ratefulto Dr. Nimal A. lernando, lead Rural linance Specialist, Asian Development

Bank, and Project fficer for the re,ional technical assistance project on Commercialization of

Microfinance, for his valuable input and ,uidance throu,hout. The authors also acknowled,e the

invaluable insi,ht and ,uidance provided to them bv Anita Campion of Chemonics lnternational in

helpin, to create and edit this studv. ln addition, sincere thanks ,o to the two formal reviewers of this

studv-Dr. Sumantoro Martowijovo (Chairman, Center for Microfinance and Small Lnterprise

Development Studies |PUSAK]) and Mr. Y. Arihadi (Director of Development for Microenterprise

lacilitatin, lnstitutions, Bina Swadava).

The authors thank all the representatives of the Oovernment of lndonesia, microfinance institutions,

donor or,anizations, and international non,overnment or,anizations, microfinance clients, and potential

clients who were so ,enerous in sharin, their experience and time. Special thanks ,o to the ADB Project

Preparatorv Team for Rural Microfinance in lndonesia (especiallv Dr. Klaus Maurer and Mr. Hendrik

Prins) for their substantial assistance in terms of data and advice. The authors also thank Dr. Mar,uerite

S. Robinson for her insi,htful contributions that have enriched the studv. ln addition, a debt of ,ratitude

is owed to Dr. Detlev Holloh for his excellent 2OO1 studv of lndonesia's microfinance institutions, which

provided substantial data to support several conclusions of this studv. ln spite of these valuable

contributions, this work is the responsibilitv of the authors, and as such, anv omissions or errors are

strictlv their own.

CONTENTS

IORWORD........................................................................................................................ iii

ACKNOWLDCMNTS ..................................................................................................... iv

ABBRVIATIONS.............................................................................................................. vii

CURRNCY QUIVALNTS AND NOTS.................................................................... viii

XCUTIV SUMMARY.................................................................................................... ix

1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1

Methodolo,v and r,anization ................................................................................................ 1

lramework for Analvzin, Microfinance Commercialization .................................................... 2

National Context ...................................................................................................................... +

2. Progress toward Microfinance Commercialization .......................................................... 9

Historical verview .................................................................................................................. 9

Lvidence of Unmet Demand................................................................................................... 11

Total Supplv............................................................................................................................. 12

Major Microfinance lnstitutions ............................................................................................. 1+

3. Conduciveness of the Operating nvironment .............................................................. 25

Lnablin, Policies ...................................................................................................................... 25

Appropriate le,al and Re,ulatorv lramework ....................................................................... 25

Lxistence of Kev Support lnstitutions ..................................................................................... 28

4. Implications of Microfinance Commercialization .......................................................... 31

Commercialization Has Allowed lar,e-scale, Sustainable utreach .................................... 31

Commercialization Has Not led to Si,nificant Mission Drift ................................................ 33

Commercialization Has Not Yet Yielded Competition ........................................................... 35

5. Microfinance Commercialization Challenges ................................................................ 37

Constraints in the peratin, Lnvironment ............................................................................ 37

lnternal Constraints ................................................................................................................ +1

COMMLPC|AL|ZAT|ON OP M|CPOP|NANCL: |NDONLS|A

vl

6. Positive Approaches to Microfinance Commercialization ............................................. 45

Roles of the Oovernment ........................................................................................................ +5

Roles of lundin, A,encies ...................................................................................................... +8

Roles of Microfinance lnstitutions .......................................................................................... +9

Roles of Kev Support lnstitutions ............................................................................................ +9

RIRNCS ..................................................................................................................... 51

ANNXS

Annex 1: Social lndicators ...................................................................................................... 55

Annex 2: Lconomic lndicators ............................................................................................... 56

NDNOTS ........................................................................................................................ 57

LXLCUT|vL SUMMAPY

vll

ABBREVIATIONS

ADB Asian Development Bank

BAPPLNAS cJcn erenccnccn em|cnuncn |cs|nc|, r National Development

Plannin, A,encv

Bl Bank lndonesia

BDB cn| Dccn c||

BKD cJcn rreJ|: Desc, or villa,e credit or,anization

BK3l cJcn rreJ|: rercs| rreJ|: nJnes|c, or Credit Union Coordination Board of

lndonesia

BPD cn| em|cnuncn Dcerc|, or re,ional development bank

BPR cn| er|reJ|:cn nc|,c:, or people's credit bank

BRl cn| nc|,c: nJnes|c, or People's Bank of lndonesia

CAMLl Capital, Asset, Mana,ement, Lquitv, and liquiditv

ODP ,ross domestic product

OLMA PKM Gerc|cn erscmc enem|cncn reucncn M||r nJnes|c, or

lndonesian Movement for Microfinance Development

OTz Oerman A,encv for Technical Cooperation

HllD Harvard lnstitute for lnternational Development

lBRA lndonesian Bank Restructurin, A,encv

KSP rercs| S|mcn |ncm, or savin,s and credit cooperative

lDKP em|cc Dcnc rreJ|: eJesccn, or rural fund and credit institution

lPD em|cc er|reJ|:cn Desc, or Villa,e Credit lnstitution

Mll microfinance institution

NBll nonbank financial institution

NO non,overnment or,anization

P+K r,e| en|n|c:cn enJcc:cn e:cn|-|e|c,cn rec||, or Small larmers'

lncome Oeneration Project

PP erum ecJc|cn

Proll Promotion of Small linancial lnstitutions project (OTz)

RlOP/P+K Rural lncome Oeneration Project, 3

rd

phase of P+K

UNDP United Nations Development Pro,ramme

COMMLPC|AL|ZAT|ON OP M|CPOP|NANCL: |NDONLS|A

vlll

CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS

(AS OF MAY 2003)

Currencv Unit - Rupiah (Rp)

$1.OO ~ Rp9,OOO

Rp1 ~ $O.OOO1

PREVIOUS YEARS

Year-Lnd Year Avera,e

1992 2,O67 2,O33

1993 2,1O2 2,O89

199+ 2,199 2,163

1995 2,287 2,2+7

1996 2,3++ 2,329

1997 3,6+6 2,776

1998 8,OOO 1O,2+8

1999 7,1OO 7,787

2OOO 9,675 8,527

2OO1 1O,+OO 1O,271

2OO2 8,9+O 9,318

USP Ln|: S|mcn |ncm, or savin,s and credit unit

USAlD United States A,encv for lnternational Development

NOTES

(i) The fiscal vear (lY) of the Oovernment ends on 31 December. ln this report, lY" before a

calendar vear denotes the vear in which the fiscal vear ends, e.,., lY2OOO ends on

31 December 2OOO.

(ii) ln this report, $" refers to US dollars.

LXLCUT|vL SUMMAPY

lx

-NA?KJELA 5K=HO -NA?KJELA 5K=HO

This report analvzes the pro,ress toward

commercialization of lndonesia's hi,hlv diversified

and predominantlv formal microfinance industrv. lt

also explores the implications of commercialization

and the remainin, challen,es to expandin, outreach

throu,h commercial microfinance institutions

(Mlls) facin, various tvpes of stakeholders

(includin, microfinance clients, microfinance

practitioners, the Oovernment, and fundin,

a,encies). ln addition, it recommends positive

approaches to the expansion of commercial

microfinance while preservin, the traditional social

objective of Mlls of expandin, access bv the poor to

demand-driven, sustainable financial services.

UNDERSTANDING MICROFINANCE

COMMERCIALIZATION

There is ,eneral acceptance of manv of the

principles associated with commercialization, but

use of the term causes discomfort amon, manv

lndonesi an stakehol ders, who associ ate

commercialization with takin, advanta,e of the

poor for the sake of profit. While in practice,

the microfinance industrv is dominated bv

commercial Mlls and institutional sustainabilitv is

,enerallv accepted as a prerequisite for the expansion

of outreach (the substance of commercialization),

terminolo,v remains an issue. Most practitioners

prefer to use the term |us|ness r|en:c:|n to reflect

the positive aspects of commercialization.

This countrv studv adopts a more comprehensive

view of microfinance commercialization than is

currentlv considered in lndonesia. lt analvzes

commercialization at micro and macro levels,

proposin, that it involves both institutional factors

(Mll commercialization) and attributes of the

environment within which Mlls operate

(commercialization of the microfinance industrv).

At the micro level, Mll commercialization

implies pro,ress alon, a continuum, described as

follows.

Adoption of a for-profit orientation in

administration and operation, such as developin,

diversified, demand-driven financial products

and applvin, cost-recoverv interest rates.

Pro,ression toward operational and financial self-

sufficiencv bv increasin, cost recoverv and cost

efficiencv, as well as expandin, outreach.

Use of market-based sources of funds, for

example, loans from commercial banks,

mobilization of voluntarv savin,s or other non-

subsidized sources.

peration as a for-profit, formal financial

institution that is subject to prudential re,ulation

and supervision and able to attract equitv

investment.

At the macro level, commercialization of the

microfinance industrv means the increased provision

of microfinance bv Mlls sharin, the above

characteristics in an enablin, environment.

Commercialization of the microfinance industrv

involves several factors, includin, the de,ree to

which the policv environment and the le,al and

re,ulatorv framework are conducive to the

development and ,rowth of commercial Mlls, the

availabilitv and access of commercial Mlls to market-

based sources of funds, and the existence of

institutions that support the microfinance industrv,

such as apex institutions, credit information bureaus,

microfinance trade associations, microfinance

technical trainin, centers, and providers of business

development services.

COMMLPC|AL|ZAT|ON OP M|CPOP|NANCL: |NDONLS|A

x

PROGRESS TOWARD COMMERCIALIZATION

The Indonesian microfinance industr, is

exceptionall, old and the main suppliers are

predominantl, formal, savings-based MIIs.

The microfinance industrv is characterized mainlv

bv formal Mlls that have adopted a commercial

approach and attained lar,e-scale outreach with a

hi,h de,ree of financial self-sufficiencv. The

industrv is verv hetero,eneous, but the re,ulated

status of the lar,est Mlls has allowed them to have

si,nificant emphasis on microsavin,s in addition

to microcredit. ne of the best known institutions

and the lar,est Mll in the world is the Bank Rakvat

lndonesia' s (BRl) Micro Business Division

(hereafter referred to as the BRl Units). Althou,h

BRl is a 1OO' state-owned limited liabilitv companv

(state bank), its financiallv self-sufficient network

of more than +,OOO units had served around 27.O

million savers and 2.8 million borrowers profitablv

as of end-2OO1 and its hi,h level of performance

has been maintained throu,h the Asian financial

crisis of 1997-1998 to the present.

While the onlv microfinance windows of the

bankin, sector with national covera,e are the BRl

Units, one private commercial bank, Bank Da,an,

Bali (BDB), has re,ional si,nificance, with 31

branches and offices located mainlv on the island

of Bali. ther major commercial Mlls include 71+

outlets of a state-owned pawnin, companv (erum

ecJc|cn, or PP) which in 2OO1 provided 22.2

million microloans to about 15.7 million clients and

the 2,1+3 locallv-owned people's credit banks (cn|

er|reJ|:cn nc|,c:, or BPRs), which, on a combined

basis, accounted for about 15' of the total

microfinance market bv number of microloans and

microdeposits in 2OO1. Althou,h the performance

of the latter is extremelv varied across institutions,

the provision of microfinance bv the svstem of BPRs

is considered hi,hlv commercial because of their

formalitv and reliance on deposits as their main

source of funds.

Several nonbank financial institutions are also

important suppliers of microfinance at the

subdistrict and village levels, but not all emplo,

a commercial approach and their performance

is extremel, uneven.

The main semiformal Mlls include over +O,OOO

outlets of a varietv of nonbank financial institutions

(NBlls). There are currentlv in operation

approximatelv +,518 villa,e-owned villa,e credit

or,anizations (cJcn rreJ|: Descs, or BKDs) that

have been providin, microfinance at the local level,

particularlv in rural Java, for more than 1OO vears.

ln addition, several tvpes of rural fund and credit

institutions (em|cc Dcnc rreJ|: eJesccn, or

lDKPs) numberin, now around 1,6OO, have been

established on the initiative of provincial

,overnments since the 197Os and are licensed,

re,ulated, and supervised bv the provincial

,overnments. Also, approximatelv half of an

estimated +O,OOO active, licensed cooperatives and

credit unions provide microfinance services.

Manv individual entities within these semiformal

NBll svstems operate on a commercial basis and

have ,ood performance records in terms of outreach,

financial self-sufficiencv, and efficiencv. As a whole,

however, thev cannot be classified as commercial due

to extreme differences in ownership, mana,ement,

and operations. lor example, BKDs are owned and

controlled bv villa,e ,overnments and their

performance varies directlv with the abilitv of

,overnment officials to mana,e small-scale financial

intermediation. ln addition, one tvpe of lDKP has

evolved into competitive financial institutions

(em|cc er|reJ|:cn Desc, or lPD) despite operatin,

primarilv in a province (Bali), which has the hi,hest

densitv of financial institutions in lndonesia, while

other tvpes of lDKPs have ,enerallv lan,uished.

linallv, the cooperative sector suffers from a lack of

national-level data concernin, its ,eneral operations

in addition to its microfinance activities, manv

efficient informal credit unions do not seek to

transform into semiformal cooperatives in order to

avoid ,overnment interference with their ,enerallv

more efficient microfinance operations.

LXLCUT|vL SUMMAPY

xl

Nongovernment organizations pla, a relativel,

minor role in microfinance provision.

nlv a few non,overnment or,anizations (NOs)

have made efforts to formalize their microfinance

activities. Contrarv to most other developin,

countries, NOs in lndonesia have mostlv been

involved with providin, trainin, and other social

services-social intermediation rather than financial

intermediation. Althou,h NOs are forbidden to

mobilize savin,s of members unless these are

deposited in a re,ulated financial institution, a few

NOs have set up their own BPRs to overcome this

constraint. As one of the oldest and lar,est NOs

in lndonesia, |nc SucJc,c is perhaps the most

prominent NO to have established a licensed bank

to carrv out its microfinance activities. This NO

has established four BPRs over the last decade. Also,

in at least one case, an NO (1c,cscn ur|c Dcncr:c,

located in Semaran,, Central Java) even mana,ed

to establish a locallv-operated commercial bank,

cn| ur|c Dcncr:c, in 199O. Another NO

(em|cc ene||:|cn Jcn enem|cncn Sum|er Dc,c,

lP2SD) in Last lombok, West Nusa Ten,,ara,

established its own credit cooperative, providin, an

umbrella for its savin,s and credit ,roups. However,

the vast majoritv of NO Mlls remains small and

unsustainable, dependent on recurrent injections of

donor funds to survive.

Covernment and/or donor supported

microcredit or microfinance programs have had

a mixed record in supporting microfinance

commercialization.

Since the 197Os, expandin, the access to credit bv

the poor has been a major part of the Oovernment's

strate,v to promote equitable ,rowth and reduce

povertv. A few interventions have helped the

commercialization of microfinance bv followin, the

new financial svstems approach," but manv

microcredit pro,rams based on the old paradi,m of

subsidized, directed credit have been harmful to the

expansion of commercial microfinance. Perhaps the

lar,est of a number of hi,h-cost, unsustainable

microcredit pro,rams was the 1993 Presidential

lnstruction on Backward Villa,es (nres Desc

Ter:|nc|, or lDT) pro,ram coordinated bv the

National Development Plannin, A,encv,

BAPPLNAS. Until it ended in 1997, the lDT

pro,ram injected a total of about Rp1.3 trillion (more

than $55O million) into infrastructure development

and povertv reduction, includin, substantial funds

for unsustainable microcredit components. ln

addition, the lamilv Welfare lncome Oeneration

Project (Lsc|c en|n|c:cn enJcc:cn re|ucrc

Sec|:erc, or UPPKS) disbursed around Rp1.+ trillion

(approximatelv $2OO million) in hi,hlv concessional

loans with 6' annual effective interest rates and less

than a 2O' cumulative repavment rate.

The most positive interventions have focused on

institutional stren,thenin, and/or savin,s

mobilization as a useful service for the poor and a

lar,e and stable source of funds for Mlls havin, clear

le,al status. A few, particularlv market-friendlv

,overnment and/or donor-sponsored pro,rams, have

been, in chronolo,ical order, the Rural lncome

Oeneration Project supported bv the lndonesian

Oovernment, Asian Development Bank (ADB), and

lnternational lund for A,ricultural Development

and implemented bv the Ministrv of A,riculture and

BRl, as part of the r,e| en|n|c:cn enJcc:cn

e:cn|-|e|c,cn rec|| (Rural lncome Oeneration

Project, P+K) pro,ram in various forms since 1979,

the transformation be,un in 1983 of the BRl Units

into a self-sustainable microfinance operation within

BRl with technical support from the World Bank,

United States A,encv for lnternational

Development, and the Harvard lnstitute for

lnternational Development, the Microcredit Project

implemented bv Bank lndonesia (Bl) with ADB

technical assistance since 1996, and the Promotion

of Small linancial lnstitutions (Proll) project , also

implemented bv Bl but with technical assistance

support from the Oerman A,encv for Technical

Cooperation (OTz) from 1999. These experiences

demonstrate how ,overnment policv toward

microfinance has been hi,hlv inconsistent.

COMMLPC|AL|ZAT|ON OP M|CPOP|NANCL: |NDONLS|A

xll

KEY ENABLING ATTRIBUTES OF THE

OPERATING ENVIRONMENT

Iinancial sector deregulation begun in the earl,

19S0s liberalized interest rates and set the stage

for the transformation of BRI Units into a self-

sufficient microfinance operation.

ne of the most important first steps lndonesian

policvmakers took to provide a conducive operatin,

environment for commercial Mlls was to liberalize

the interest rate in 1983, which set the sta,e for Mlls

to char,e cost-recoverv interest rates and maintain

spreads that allowed profitabilitv. ln addition, hi,h-

level political support for the transformation of BRl

Units durin, 1983/8+ from a,ricultural credit

disbursement centers to a commerciallv-oriented

svstem for micro and small-scale lendin, resulted

in an increase in microfinance services for 27.O

million savers and 2.8 million borrowers as of

end-2OO1.

A tiered legal and regulator, framework

stemming from the 19SS banking reforms has

allowed the expansion of unit (rural) banks

conducive to commercial microfinance

operations throughout Indonesia.

The series of reforms be,un in 1988, collectivelv

referred to as PAKT, removed most bankin,

industrv entrv barriers, allowin, commercial banks

to extend their branch network throu,hout

lndonesia. This reform packa,e had the objective of

expandin, the outreach of financial services to rural

areas. The Oovernment also permitted the

establishment of new secondarv banks at the

subdistrict level with paid-up capital of onlv Rp5O

million (equivalent to $6,25O at end-1998). More

than 1,OOO new BPRs were established durin, the

followin, 5 vears. The Bankin, Act of 1992 finallv

reco,nized BPRs as secondarv banks, while

Presidential Decree No. 71 of 1992 required lDKPs

to seek a BPR license until ctober 1997. f the

lDKPs, 63O converted to BPRs between 199+ and

earlv 1999 and these transformations account for

almost two thirds of the BPR industrv's ,rowth durin,

that time. ln addition, the 1989 bankin, reform

packa,e allowed BPRs to open branches in other

subdistricts outside the national, provincial, and

district capitals, to up,rade or mer,e with commercial

banks, and to mer,e with other BPRs.

Recent regulations accommodating bank

operations based on Sharia principles (Islamic

banking) ma, open access to microfinance

services for a new and potentiall, significant

subset of the population.

Bankin, Act No. 1O of 1998 and Bankin, Act No.

23 of 1999 have mandated and ,iven le,al basis for

Bl to develop lslamic bankin, in lndonesia, the

world's most populous Muslim countrv. lslamic

bankin, is based upon a renewed application of

lslamic law, the Sharia, to modern economic and

financial transactions. Bevond its reli,ious

implications, lslamic bankin, involves a conceptuallv

different relationship between finance and economic

activities. The development of a le,al and re,ulatorv

framework to support bankin, based on Sharia

principles mav help to shift focus from traditional

collateral requirements to the merits of business

proposals as a basis for lendin, decisions. This chan,e

in emphasis tvpicallv associated with lslamic bankin,

mav improve microcredit access bv the poor who

have cultural reservations to conventional credit or

are without traditional collateral.

Since 199S, the Covernment has been

endeavoring to strengthen BI significantl,,

enhance prudential regulation and supervision

of the banking sector, and improve the legal

and regulator, framework for microfinance.

Bankin, Act No. 1O of 1998 amended Bankin, Act

No. 7 of 1992 and with it substantial chan,es were

introduced includin, the transfer of licensin,

authoritv from the Ministrv of linance to Bl, the

liftin, of forei,n bank ownership restrictions, the

limitation of bank secrecv to information on deposits,

and provisions for the formation of a deposit

protection institution and the bank restructurin,

LXLCUT|vL SUMMAPY

xlll

a,encv. ther special re,ulations dealt with fit and

proper tests, bank mer,ers and acquisitions,

revocation of business licenses, and bank liquidation.

Compliance-based supervision was complemented

with risk-based supervision and a set of Bl decrees,

such as on loan loss provision requirements,

minimum capital requirements, assessment of asset

qualitv, le,al lendin, limits, and financial reportin,

was desi,ned to improve prudential bankin, practices

in accordance with international standards.

Article 3+ of Bankin, Act No. 23 of 1999

concernin, Bl mandated that there be a new

institution for consolidatin, supervision of the

financial sector. ln accordance with this mandate,

the bank supervision function will be transferred from

Bl to a new independent institution, which will likelv

be established in 2OO3. With the transfer of this

supervision function, Bl will concentrate on

monetarv and pavment svstem issues. The new

supervisorv institution will put more emphasis on

effectivelv enforcin, bank compliance with

prudential re,ulation and NBll re,ulation and

supervision. lt is planned to be a ,overnment

institution outside the cabinet, accountable to the

President. The objective of the institution will be to

supervise all financial service institutions in the

framework of creatin, a healthv, accountable, and

competitive financial services industrv." The

covera,e of the institution will include the

supervision of banks and all NBlls, such as insurance

and venture capital companies, pawn companies,

leasin, companies, pension funds, securitv

companies, and other financial service companies,

includin, those mobilizin, deposits from the public.

Manv tvpes of Mlls, such as BKDs, lDKPs, and

other NBlls without licenses as banks or re,istration

as cooperatives, mobilize public deposits in violation

of the Bankin, Act. ln order to address this issue

and provide a le,al basis for small-scale Mlls to

operate under appropriate, adapted prudential

re,ulation and supervision, a team comprised of

representatives from the Coordinatin, Ministrv of

Lconomics, Ministrv of linance, Ministrv of

Cooperatives and Small and Medium Lnterprises,

Ministrv of Home Affairs, Ministrv of A,riculture,

Nati onal Devel opment Pl anni n, A,encv

(BAPPLNAS), BRl, a microfinance network

called OLMA PKM (see below), and supported

bv the OTz Proll project, has been formulatin, a

draft Mll Act since March 2OO1. An initial full

draft of the microfinance law was sent to the

Mi ni strv of li nance f or consi derati on i n

September 2OO1 and several revised versions have

been receivin, consideration since. The process

i s l eadi n, to appropri ate re,ul ati on and

supervision of microfinance in order to provide

an enablin, le,al and re,ulatorv environment for

commercial Mlls and the protection of the

savin,s of small depositors.

Several ke, industr, support institutions have

assisted the commercialization of a wide variet,

of MIIs.

The most inclusive national microfinance network,

the lndonesian Movement for Microfinance

Development (OLMA PKM, Gerc|cn erscmc

enem|cncn reucncn M||r nJnes|c) has been

an active partner in draftin, new laws and re,ulations

on microfinance and is committed to promotin,

awareness and adoption of best practices in

microfinance as a tool for sustainable povertv

reduction and economic ,rowth. ln addition,

er|cr|nJ, the main national association of BPRs,

has been providin, trainin, on microfinance for vears

and is now developin, capacitv-buildin, tools in

coordination with OTz and Bl to stren,then BPR

performance and increase access to market sources

of funds. Also, the Credit Union Coordination Board

of lndonesia (BK3l), the national apex or,anization

for the cooperative movement and its re,ional

chapters, aims to stren,then the development of

autonomous and self-reliant cooperatives. Trainin,,

insurance, interlendin,, and supervision are major

tasks carried out bv the secondarv structures of the

movement (i.e., 16 of the 28 re,ional chapters

established bv BK3l that have adopted the status of

secondarv cooperatives).

COMMLPC|AL|ZAT|ON OP M|CPOP|NANCL: |NDONLS|A

xlv

IMPLICATIONS OF COMMERCIALIZATION

Commercialization has allowed large-scale,

sustainable microfinance outreach.

Support for commercialization of microfinance is

primarilv based on the assumption that

commercialization assists lar,e-scale expansion of

sustainable microfinance, and the lndonesian case

provides positive evidence for this assumption.

Savin,s mobilization bv predominantlv formal Mlls

has fueled broad microcredit outreach. lor example,

at the end of 2OO1, savin,s mobilized bv the BRl

Units in the S|meJes savin,s product alone (Rp15.9

trillion, or $1.5 billion) were 1.61 times the amount

of their total outstandin, loan portfolio (Rp9.8

trillion, or $9+6.3 million). Deposit mobilization is

also important for BPRs, which, on a combined basis,

funded 9O' of their outstandin, loan portfolio

(Rp5.6 trillion, or $6O+.O million) with deposits

(Rp5.1 trillion, or $53+.6 million).

Microfinance commercialization has resulted

in a wide scope of sustainable outreach.

Various tvpes of pawnin, services are readilv

available, as are flexible loan and deposit products

and, to a lesser extent, pavment and monev transfer

services. Perhaps most remarkable about the

lndonesian experience is that commercialization has

allowed the sustainable expansion of microsavin,s

services on an unprecedented scale in addition to

expandin, access to microcredit. Commercialization

has contributed to chan,in, perceptions, at least on

the part of practitioners, that microsavin,s are also

a valuable service for the poor in addition to bein, a

stable source of funds to support ,rowth in the

microloan portfolio. lmportantlv, the outreach of

commercial Mlls has proven to be sustainable, and

at no better time was this witnessed than durin, the

Asian financial crisis.

Commercial MIIs have a good record in

reaching the poor, although outreach coverage

is incomplete in less populated rural areas.

Althou,h the avera,e microcredit loan amount

varies widelv, the number and amount of microloans

as a percenta,e of ODP per capita are less than most

other microfinance markets in the world. Lven the

avera,e outstandin, loan size of the BRl Units

($337), which is the hi,hest amon, major

commercial Mlls in lndonesia, is onlv half the ODP

per capita ($68O) and low compared to the avera,e

for Mlls worldwide ($+53). The BRl Units and even

some of the BPRs have had success in pioneerin,

and expandin, villa,e units and mobile services in

manv areas. However, in ,eneral, commercial Mlls

have had limited success in reachin, down to the

villa,e level and to less populated areas.

Commercialization has not led to significant

mission drift.

Contrarv to the common assumption that the

process of Mll commercialization will shift an Mll's

tar,et market from the poor to the less poor and

nonpoor (i.e., mission shift), this has not happened

in lndonesia in anv si,nificant wav. lndicators of

mission drift include increasin, effective interest

rates char,ed on microloans, increasin, avera,e

outstandin, loan amounts, and chan,e in percenta,e

of low-income female clients to hi,her-income male

customers. lew, if anv, Mlls have exhibited these

chan,es to anv si,nificant extent. This mav be due

in lar,e part to the fact that more than 8O' of the

microcredit is supplied throu,h the two state-owned

institutions, PP and the BRl Units, that remain

committed to the social mission of servin, the

economicallv-active poor. PP and the BRl Units

operate on hi,hlv commercial terms when

considerin, their deliverv of demand-driven

products, and use pricin, that allows profitabilitv and

access to market-based sources of funds. nlv their

lack of private ownership prohibits consideration of

these market leaders as fullv commercial institutions.

Commercialization has not ,et brought about

competition.

Competition between Mlls is not a factor so far,

althou,h some competitive pressures exist with banks

LXLCUT|vL SUMMAPY

xv

competin, for deposits at the district level and above,

and some localized competition is heatin, up in a

few more hi,hlv populated subdistricts. The BRl

Units' dominance as a nationwide unit svstem within

a state-owned bank hinders competition and has

made deposit mobilization and liquiditv mana,ement

bv other Mlls, such as BPRs (havin, no transfer

pricin, mechanism and/or implicit ,overnment

,uarantee of deposits), more costlv and difficult than

if a level plavin, field existed.

MICROFINANCE COMMERCIALIZATION

CHALLENGES

ver the last 2O vears, the ,rowth of commercial

Mlls in lndonesia has led to si,nificant breadth,

depth, scope, and sustainabilitv of outreach. The

,reatest challen,e presentlv facin, the lndonesian

microfinance industrv is to expand access bv the poor

and near poor to microfinance at the villa,e level

and in more remote, less denselv populated areas.

However, several challen,es to expandin, access to

commercial microfinance exist at the macro

(operational environment) and micro (institutional)

levels. Below are a few of the most pressin,

challen,es.

Constraints in the Operating Environment

Subsidized, directed microcredit programs that

inhibit private sector microfinance initiatives

A recent ADB report on the microfinance sector

found that there are 7O pro,rams and projects for

povertv reduction under various ministries and other

national ,overnment institutions and that manv of

these have a microcredit or microfinance

component. These pro,rams have lar,e fundin,

allocations with their combined bud,et allocation

in lY2OO2 alone amountin, to Rp16.5 trillion ($1.8

billion). f the 7O total national ,overnment-

sponsored povertv reduction pro,rams, at least 16

were identified that address povertv issues under a

lon,-term strate,v of the Oovernment, mostlv

supported bv such donors as the World Bank, ADB,

and OTz. These pro,rams have a total bud,et of

almost Rp3 trillion ($33O million). Most of these also

include a microcredit or microfinance component.

Althou,h well-intended, manv of these pro,rams do

not follow established microfinance best practices

and have undermined rather than supported

sustainable microfinance. Specificallv, thev mix

,rants and credit, thev do not clearlv separate

financial and social intermediation, and thev

frequentlv applv subsidized interest rates. ln addition,

followin, ,overnment dere,ulation, numerous and

increasin, district-level povertv reduction pro,rams

have been established that also contain microcredit

or microfinance components adverse to the

expansion of commercial microfinance. Both the

national-level pro,rams and re,ional or district-level

pro,rams have the potential to increase in the future

,iven the upcomin, 2OO+ elections and the possibilitv

of usin, subsidized, directed microcredit pro,rams

to attract voters.

Deposits mobilized b, NBIIs at risk

With more than +,5OO BKDs, around 1,6OO

lDKPs, more than +O,OOO microfinance

cooperatives, in excess of 1,OOO credit unions, and

around +OO microcredit NOs, institutional

proliferation has led to market se,mentation and a

multitude of relativelv weak Mlls at the villa,e level.

ln some cases, the le,al framework re,ardin, this

wide varietv of NBlls is unclear, in others, it is simplv

inappropriate or absent. limited savin,s mobilization

has been tolerated, but because there is little or no

enforced supervision and reportin, requirements for

most of these NBlls, these small savin,s are at risk

of loss. This issue is especiallv important because the

best estimates indicate that these NBlls mav have

collectivelv mobilized more than Rp1,871 billion

($2O9 million) in deposits in recent vears. lf a

si,nificant amount of client savin,s were lost, it

would be a challen,e for microfinance institutions

to continue to attract savin,s, which are an

important commercial source of funds, at a

reasonable interest rate.

COMMLPC|AL|ZAT|ON OP M|CPOP|NANCL: |NDONLS|A

xvl

Weaknesses in BPR regulation and supervision

The BPR re,ulatorv re,ime has been based on that

of commercial banks and is not appropriate to the

specialized operations of these microbanks. ln some

areas, the re,ulations are overlv strict and in others

the existin, re,ulations are too lax, especiallv in terms

of loan classification, provisionin,, and write-offs.

ne of the most obvious constraints facin, the BPRs

in their expansion of commercial microfinance is the

hi,h minimum capitalization requirements stipulated

bv recent BPR re,ulations. Bl Decree No. 32

(sections 35 and 36), enacted in Mav 1999, stated

that the minimum capital requirement to establish

a BPR or a branch is increased from Rp5O million to

Rp2 billion (equal to $192,3O8 at end-2OO1) for the

national capital area.

+

Simultaneouslv, Bl increased

minimum capital requirements to Rp1 billion

($96,15+) for provincial capitals and Rp5OO million

($+8,O77) for other areas. With a minimum paid-up

capital 1O times hi,her than the previous capital

requirement, new BPR establishment in rural areas

is practicallv impossible. These hi,h entrv barriers

contradict the idea of the bankin, reforms in the

late 198Os and earlv 199Os, which were ,eared toward

the expansion of bankin, in rural areas. The

intention of the 1999 re,ulatorv chan,es was to

develop a sound industrv with fewer but lar,er BPRs.

ln fact, onlv 13 new BPR licenses were issued over

the first 3 vears followin, the increase in capital

requirements. The requirement chan,es the BPR

character from a local secondarv bank to a small

primarv bank, but it does not necessarilv improve

the soundness of the industrv.

5

Political econom, of cooperatives

Provisions made in the Cooperative law le,alize

direct ,overnment intervention into the cooperative

sector and even require the Oovernment to provide

protection and preferential treatment. Their use to

channel funds to tar,eted beneficiaries has

completelv corrupted the inte,ritv of cooperatives

as viable institutions. As lon, as this practice

continues, it is difficult to proceed with institutional

capacitv buildin,. ln principle, the cooperative

or,anization of microfinance, especiallv at the villa,e

level, has ,reat potential in lndonesia. However,

usin, this potential amid the poor state and

reputation of the cooperative sector is foremost a

political question. lt requires a new political

consensus in the post-New rder era about the role

of the State in cooperative development, which

should chan,e from direct intervention to

policvmakin,.

6

Caps and deficiencies in cooperative law

There exists a basicallv sound re,ulatorv framework

for the primarv and secondarv savin,s and credit

cooperatives (rercs| S|mcn |ncm, or KSPs) and

savin,s and credit units (Ln|: S|mcn |ncm, or

USPs) that are separated from other business units

of primarv or secondarv cooperatives. Provisions for

financial soundness and supervision exist and can

support the development of cooperatives. However,

the prudential framework for cooperatives has a few

serious inadequacies and ,enerallv lacks adequate

sanctions and penalties for noncompliance. lor

example, the loan classification svstem is lax and

there are no requirements for loan loss provisionin,.

Capital is not properlv defined and there are no

sanctions for a capital ratio of less than 2O'. Moreover,

the CAMLl (Capital, Asset, Mana,ement, Lquitv,

and liquiditv) ratin, svstem in use should be simplified

and there should be sanctions for low ratin,s. The

re,ulations also include provisions that tend to force

small and informal ,roups with savin,s and credit

activities into the semiformal cooperative sector. ln

addition, the supervisorv re,ime for cooperatives is

unclear: one re,ulation refers to ,uidance," another

to supervision," and still another to controllin,

measures." There is also no capacitv in the Ministrv

of Cooperatives and Small and Medium Lnterprises

7

to supervise or even to ,uide KSPs/USPs. ln addition,

deposit protection applies onlv to banks. The

Ministrv is aware of the deficiencies of the present

svstem, but is constrained bv a lack of resources and

the fact that it has lar,elv lost control of supervision,

,uidance, and enforcement. These functions have

LXLCUT|vL SUMMAPY

xvll

been decentralized to the provincial and district

,overnments.

Lack of a deposit insurance institution

The policv to provide a blanket deposit ,uarantee

durin, the hei,ht of the financial crisis in order to

re,ain public confidence in the bankin, sector

proved effective in 1998. Within a short time,

deposits flowed back into the bankin, svstem and

currentlv public savin,s have reached approximatelv

7O' of total bank assets.

8

However, behind this

success is the lar,e financial burden that has to be

borne bv the Oovernment and the potential moral

hazard in the bankin, sector. A more effective and

sustainable ,uarantee of savin,s is required.

No credit information bureau

The exchan,e of information between the BPRs,

BRl Units, and Bl is common, althou,h done on an

ad hoc basis. Tvpicallv, the BPRs ask BRl or other

BPRs whether or not a credit applicant is indebted

to other banks. law No. 1O of 1998 stipulates that

Bl shall facilitate such exchan,e of information. ln

an attempt to implement its task more effectivelv

and efficientlv, Bl, at the end of March 2OOO,

conducted a reor,anization at the Directorate of

Credit, which formerlv comprised five divisions, into

a Credit Administration and Mana,ement Division

with a Development Team to create a credit

information svstem. Bl saw the need to formulate

policv on technical support for credit extension to

micro and small-scale businesses. The ,oal of its

Credit lnformation Svstem Lnhancement Project is

to develop the hi,hest qualitv of information possible,

and is lookin, to learn from credit bureau development

in other countries, such as Thailand and Australia.

Absence of a local microfinance training

institution

Qualitv trainin, at reasonable prices for both Mll

mana,ers and line staff to promote mana,ement and

retailin, capabilities in line with best practices in

microfinance is virtuallv nonexistent in lndonesia.

Althou,h BRl conducts some trainin, courses and

BPR-specific trainin, is provided bv er|cr|nJ, there

is no one-stop shop" for qualitv, demand-driven and

cost-effective trainin, in microfinance on a re,ular

basis.

Internal Constraints to

MFI Commercialization

BRI Units

The achievements of the BRl Units in terms of

financial self-sufficiencv and outreach have been

without parallel elsewhere in the world, but thev also

have a few important shortcomin,s and areas of

untapped potential. Despite the hi,h profitabilitv of

the BRl Units, their status as a profit center within a

state-owned bank puts the svstem's financial self-

sufficiencv at some risk and at no time was this made

clearer than durin, the recent Asian financial crisis.

Use of Unit profits to cover losses made in other

departments at BRl en,a,in, in lar,er-scale lendin,

has inhibited the expansion of rural microcredit.

BPRs

BPR outreach is concentrated in urban areas of

Java and Bali provinces (comprisin, some 82' of

the total number of BPRs).

9

utreach into outlvin,

provinces and their rural areas is verv limited. The

main constraint to expandin, the BPR industrv into

new re,ions and markets relates to the hi,h minimum

capitalization requirements that limit the abilitv of

BPRs to form branches. lack of a network also poses

a constraint to BPR expansion in terms of abilitv to

distribute credit risk ,eo,raphicallv, to mana,e bank

liquiditv needs, and to provide customers with

possibilities to withdraw savin,s or otherwise access

their accounts in other areas.

LDKPs

wnership of lDKPs bv traditional villa,e

administrative units called Desc -Jc: suffers from

COMMLPC|AL|ZAT|ON OP M|CPOP|NANCL: |NDONLS|A

xvlll

communal conflicts that affect mana,ement and

operations, also weak enforcement abilitv in some

cases undermines ,ood performance. ln addition,

structural weakness of the support svstem available

to lPDs in need of technical assistance affects

potential ,rowth opportunities. Supervision of

lDKPs is not clearlv separated from technical

assistance to these institutions and involves too manv

parties to be effective. The lack of consistent national

re,ulatorv framework is another constraint. The

former requirement to convert lDKPs to BPRs did

not reflect the needs of such institutions as lPDs.

This led Bl to allow lPDs to operate temporarilv as

nonbanks without solvin, the underlvin, problem

of uneven performance bv lDKPs as a whole.

1O

BKDs

As ownership and le,al form are va,ue, and

mana,ement and control functions are not clearlv

separated, BKDs lack effective ,overnance and

supervision bv owners. Althou,h the BKD industrv

has comparative advanta,es in operatin, on a part-

time basis within a limited and familiar environment,

the BKD industrv as a whole is held back bv a lack

of dvnamism. ln addition, BKDs lack stron, market

orientation, skilled human resources, and the svstems

required for small banks.

11

POSITIVE APPROACHES TO

COMMERCIALIZATION

Stop the provision of subsidized, directed

microcredit.

The main roles that the Oovernment should plav in

the commercialization of microfinance are to create

and maintain an enablin, macroeconomic and

sectoral policv environment and an appropriate le,al

and re,ulatorv framework for microfinance. Supplv-

led subsidized microcredit pro,rams should be

replaced bv demand-led microcredit with interest

rates that at least cover the costs of financial

intermediation. The Oovernment needs to shift

resources from subsidized credit pro,rams to capacitv

buildin, for expanded sustainable outreach bv

microfinance providers includin, banks, as well as

for operators of microenterprises and small

businesses.

Strengthen BPR regulation and supervision.

To expand the abilitv of BPRs to branch and expand

services to villa,es, consideration should be ,iven

to reducin, the capital entrv requirements for new

BPRs and removin, the requirement that new

branches have the same capital requirements as for

the head office. The prohibition of forei,n

investment in BPRs should be rescinded. BPRs

should also be allowed to provide insurance services

provided thev do not take the underwritin, risk.

With OTz assistance under the Proll project, Bl

has worked to improve the re,ulatorv re,ime for

BPRs and the information flow to Bl to make off-

site supervision of BPRs more effective, and has

substantiallv stren,thened sanctions and penalties

for noncompliance with re,ulations. This work

should continue with a view to increasin, capital

adequacv ratios, developin, a stricter loan

classification svstem, increasin, loan-loss

provisionin, levels, simplifvin, and improvin, the

CAMLl ratin, svstem, reducin, le,al lendin,

limits, improvin, the information flow to Bl to make

off-site supervision more effective, and substantiallv

stren,thenin, sanctions and penalties for

noncompliance with re,ulations. Bl's Board is likelv

to approve the new re,ulations in 2OO3. OTz is

alreadv providin,, and will continue to provide

(durin, 2OO3-2OO5), comprehensive technical

assistance to Bl at the national and re,ional level

to implement the new re,ulations, improve

supervision, train supervisors, and improve manuals

for on- and off-site inspection.

Iormulate activit,-based regulation and

supervision.

Some adaptations of re,ulations for microfinance

banks that should be considered include

LXLCUT|vL SUMMAPY

xlx

adjustin, minimum capital requirements to be

low enou,h to attract new entrants into

microfinance, but hi,h enou,h to ensure the

creation of a sound financial intermediarv,

assessin, the riskiness of microfinance operations

based on overall portfolio qualitv and repavment

historv, rather than on the value of traditional

,uarantees,

increasin, capital adequacv ratios to 15-2O',

dependin, on performance,

requirin, stricter loan loss provisionin,, and

allowin, hi,her administrative cost ratios.

With the redefined role of Bl, the Ministrv of linance

should take the lead in promotin, microfinance and

considerin, the formulation of new activitv-based

re,ulation and supervision for microfinance. A

special unit-or even directorate-for micro-

finance development in the Ministrv of linance mav

be required.

Improve the legal and regulator, framework

for cooperatives.

Cooperative laws and re,ulations should be reviewed

with the followin, objectives:

withdraw the Oovernment from the cooperative

sector and stren,then the institutional autonomv

of microfinance cooperatives,

terminate their preferential treatment and

protection,

stren,then participation of and internal control

bv members,

limit savin,s mobilization and credit extension

to ordinarv members,

establish an independent and effective

supervisorv re,ime, and

abandon the explicit task of local officials to

motivate" small informal ,roups at the villa,e

level to convert to formal cooperatives.

lorced formalization should not be part of an

enablin, re,ulatorv framework. Small, villa,e-level

,roups need time to learn how to mana,e their own

funds and often will not develop into lar,er financial

intermediaries. lt is neither desirable nor realistic that

the state bureaucracv should oversee some 1O,OOO

of these ,roups. An effective supervision svstem for

microfinance cooperatives should be separate from

the financial and technical support functions of the

Ministrv of Cooperatives and be able to enforce

compliance with prudential re,ulations.

Assess the feasibilit, of establishing an apex

bank for BPRs.

To overcome some of the challen,es associated with

their unit bank structure, BPRs should explore the

possibilities of linkin, to national or at least re,ional

networks in order to facilitate interbank liquiditv

transfers and to provide their customers with

possibilities of accessin, their accounts in other areas

of the countrv. Perhaps the most promisin, wav to

overcome the challen,es associated with unit

bankin, would be to open an apex bank for the

svstem of BPRs. Such an apex bank could assist BPRs

with liquiditv and fund mana,ement and enable

them to provide their clients with monev transfer

services. ln addition, the apex bank mi,ht also assist

in distributin, costs related to trainin, and svstems

development.

Iacilitate the provision of deposit insurance.

n,oin, work to establish a deposit insurance

institution should be continued. To provide a more

effective ,uarantee of savin,s, a team comprised of

representatives from Bl, Ministrv of linance, and

lndonesian Bank Restructurin, A,encv has been

appointed with the task of preparin, for the

establishment of the deposit insurance institution

em|cc encm|n S|mcncn, or lPS. The team's

short-term a,enda is to formulate a phaseout for the

COMMLPC|AL|ZAT|ON OP M|CPOP|NANCL: |NDONLS|A

xx

,uarantee covera,e on almost all bank obli,ations,

it would be limited to savin,s, collections, incomin,/

out,oin, transfers, interbank lendin,, and letters of

credit. The lon,-term a,enda is to establish the

deposit insurance institution usin, limited ,uarantee

covera,e. Membership in the lPS is expected to be

compulsorv for all banks bv 2OO+.

Improve BPR institutional capacit,.

lncreased attention should be ,iven to buildin, human

resource stren,th in financial analvsis and bankin, so

that strate,ic plannin, and business plans to

operationalize such plannin, can be made. Active

participation in er|cr|nJ should also take prioritv in

order to exchan,e positive and ne,ative experiences,

learn about local and international best practices, and

access various tvpes of professional microfinance

trainin, services, such as the trainin, pro,ram bein,

supported bv the Proll project. lnvestments in

human resource and product development are verv

costlv and cannot be covered in the lon, term bv a

sin,le bank with a small capital base, thus access

to support services is crucial for a BPR involved in

microfinance. The development of strate,ic

alliances with other financial institutions could also

be a means to access these services at low cost.

Assess potential for privatizing the

BRI Units and PP.

Both the BRl Units and PP operate on a profitable

basis despite bein, public enterprises. Althou,h BRl

became a limited liabilitv companv in 1992, 1OO'

of its shares are still owned bv the State. Oiven the

risks that the BRl Units face in terms of havin, their

profits diverted bv other divisions within BRl to

unprofitable investments, the Oovernment should

,ive some consideration to the potential for at least

partiallv privatizin, the BRl Units in a wav that will

ensure maintenance of the svstem's focus on

microfinance. ne disadvanta,e of this would be that

the Units mav not have the same lucrative internal

market for excess deposits. However, privatization

mav encoura,e them to move down market for

further lendin,. PP also appears readv for at least

partial privatization because it is not onlv profitable

but also able to raise funds in the domestic bond

market. Therefore, the Oovernment should stop

providin, cheap funds to PP. The proceeds of

divestiture could be used for social safetv nets and/

or for prioritv investments in phvsical infrastructure.

Promote the establishment of a local,

commerciall,-oriented microfinance training

center.

The absence of a stron,, commerciallv-oriented,

microfinance trainin, center is a major reason whv

microfinance retailin, capacitv remains low at

institutions lackin, an in-house trainin, pro,ram.

Creation of a one-stop shop" could help the

microfinance industrv build the local technical

capacitv it needs for further professionalization and

commercialization. Donors should use a portion of

their ,rant funds that currentlv support subsidized

microcredit interest rates to finance at least part of

the start-up costs of a microfinance trainin, center.

ln addition, donors should promote institutionalized

linka,es between Mlls (i.e., bv stren,thenin, the

OLMA PKM network) and also promote Mll

cooperation with re,ional and international financial

and technical service providers.

Invest in social intermediation and ph,sical

infrastructure development, especiall, in rural

areas.

The Oovernment should exchan,e direct

interventions in povertv lendin, with indirect

approaches, such as promotin, the development of

kev microfinance support institutions and investin,

in social intermediation infrastructure development.

Short-term, subsidized microcredit interventions

should be separated from social safetv nets or

emer,encv pro,rams and replaced with lon,er-term,

commercial strate,ies that support the balanced

,rowth of savin,s, investment, and repavment

capacities. lurther development of phvsical

infrastructure should focus on improvin,

LXLCUT|vL SUMMAPY

xxl

communications and transportation, which would

reduce transaction costs and risks of microfinancial

intermediation, especiallv in more remote rural areas.

The emphasis of social intermediation efforts should

be support for microfinance commercialization bv

helpin, access to convenient and safe savin,s

instruments, which allow low-income ,roups,

includin, the extremelv poor, to mana,e their

liquiditv and accumulate funds for special

expenditures.

This report analyzes the progress toward

commercialization of Indonesias highly

diversified and predominantly formal

microfinance industry. It also explores the

implications of commercialization and the

remaining challenges to expanding outreach

through commercial microfinance institutions

(MFIs) facing various types of stakeholders

(including microfinance clients, microfinance

practitioners, the Government, and funding

agencies). In addition, it recommends positive

approaches to the expansion of commercial

microfinance while preserving the traditional

social objective of MFIs of expanding access

by the poor to demand-driven, sustainable

financial services.

METHODOLOGY AND ORGANIZATION

This study on which this report is based

includes theoretical considerations drawn

from the financial systems paradigm

12

and

practical field experience for analyzing the

commercialization of microfinance. The main

findings and recommendations presented here

are the product of extensive consultation through

individual and group meetings with a wide

variety of MFIs and stakeholders including

microfinance clients, government officials,

state-owned commercial banks, private banks,

cooperatives, domestic and international

nongovernment organizations (NGOs), funding

agencies, and academics. In addition, because of

the extreme diversity and numbers of MFIs

operating at the village level throughout

Indonesia, this study relies heavily on existing

microfinance literature.

Responses to questi onnai res el i ci ti ng

stakehol der vi ews on mi crofi nance

commercialization and their latest institutional

and financial data have been incorporated

where possible. In addition to collecting such data

and holding a wide variety of stakeholder

meetings in Jakarta, the authors also gathered data

during field visits to several other provinces.

13

It

is important to note that all institutional and

financial data are based on self-reporting by the

MFIs surveyed by the authors, unless otherwise

noted. Readers should be mindful that these self-

reported data provided by MFIs and included in

this report are often based on estimates only. This

is particularly an issue with NGOs providing

microfinance (microfinance NGOs) that do not

separate microfinance from other social programs

or from traditional financial intermediation (as

with many banks and cooperatives).

The remainder of this chapter elaborates on

the framework for anal yzi ng the

commercialization of microfinance used

throughout the study and establishes the

country context as it affects the microfinance

industry. Chapter 2 examines the historical

development of the microfinance industry,

eval uates maj or commerci al MFIs and

microfinance programs, and assesses MFI

access to commercial sources of funds. Chapter

3 analyzes the conduciveness of the operating

environment to the commercialization of

microfinance by focusing on enabling attributes

of the policy environment and the legal and

regulatory framework, and the existence of key

microfinance support institutions. Chapter 4

explores the implications of commercialization

in terms of expected changes in access to

microfinance by client type, in the mix of

microfinance products and services offered, and

in access to commercial sources of funds.

Empirical evidence of and potential for

competition and mission drift are also assessed

in Chapter 4. Current challenges to microfinance

commercialization are the focus of Chapter 5,

which reveals stakeholder perceptions, internal

constraints facing MFIs, and external

lntroduction lntroduction

COMMLPC|AL|ZAT|ON OP M|CPOP|NANCL: |NDONLS|A

2

impediments in the operating environment.

Chapter 6 recommends positive approaches

to commercialization for the Government,

funding agencies, various types of MFIs, and

microfinance support institutions.

FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYZING

MICROFINANCE COMMERCIALIZATION

There is general acceptance of many of the

principles associated with commercialization,

but use of the term causes discomfort among

many Indonesian stakeholders, who associate

commercialization with taking advantage of the

poor for the sake of profit. While in practice,

the microfinance industry is dominated by

commerci al pl ayers and i nsti tuti onal

sustainability is generally accepted as a

prerequisite for the expansion of outreach (the

substance of commercialization), terminology

remains an issue. Most practitioners prefer to

use the term business orientation to reflect the

positive aspects of commercialization. The

term commercialization in Indonesia carries a

negative connotation and is perceived more

to i ndi cate excessi ve profi tabi l i ty than

sustainability. This concept of commercialization

is distinct from the favorable one held by many

microfinance professionals worldwide.

International microfinance professionals are

increasingly considering commercialization to be

the application of market-based principles to

microfinance or the expansion of profit-driven

microfinance operations.

14

There is a growing

realization in the international arena that

commercialization allows MFIs greater

opportunity to fulfill their social objectives of

providing the poor with increased access to an

array of demand-driven microfinance products

and services. In Indonesia, however, euphemisms

such as surplus are traditionally used in place

of profit and institutional sustainability is

used as an acceptabl e catch-al l phrase

i ndi cati ng many of the pri nci pl es of

commercial microfinance elaborated in this

study. Few Indonesian stakeholders hold the

view that commercialization allows MFIs

greater opportunity to fulfill their social

objectives of providing the poor with increased

access to an array of demand-driven microfinance

products and services (including not only credit

but also savings, insurance, payments, money

transfers, etc.).

Thi s country study adopts a more

comprehensi ve vi ew of mi crofi nance

commercialization than is currently considered

in Indonesia. It analyzes commercialization at

two levels, proposing that it involves both

institutional factors (MFI commercialization)

and attributes of the environment within which

MFIs operate (commercialization of the

microfinance industry).

MFI Commercialization

MFI commercialization is considered as

progress along a continuum, as depicted in Figure

1.1 and described below.

Adoption of a professional, business-like

approach to MFI administration and

operation, such as developing diversified,

demand-driven microfinance products and

services and applying cost-recovery interest

rates.

Progression toward operational and financial

self-sufficiency by increasing cost recovery

and efficiency, as well as expanding outreach.

Use of commercial sources of funds; for

example, nonsubsidized loans from apex

organizations (wholesale lending institutions)

or commercial banks, mobilization of

voluntary savings, or other market-based

funding sources.

Operation as a for-profit, formal

15

financial

institution that is subject to prudential

regulation and supervision and able to attract

equity investment.

Progress toward MFI commercialization is

usually hastened by a strategic decision of an

|NTPODUCT|ON

3

MFIs owners/managers to adopt a for-profit

orientation accompanied by a business plan to

operationalize the strategy to reach full financial

self-sufficiency and to increasingly leverage its

funds to achieve greater levels of outreach. The

recognition that the key to achieving substantial

levels of outreach is building a sound financial

institution, essentially means that MFIs need to

charge cost-covering interest rates and continually

strive for increasing operational efficiency.

Advocates of this approach rightly argue that

charging cost-covering interest rates is feasible

because most clients would have to pay, and

indeed do pay, even higher interest rates to

informal moneylenders. MFIs that charge cost-

covering interest rates are an attractive option for

this clientele even though the interest rates that

an MFI might charge may seem high relative to

the corresponding cost of borrowing from a

commercial bank. The relevant basis for interest

rate comparisons in the eyes of the client is the

informal sector where he or she usually can access

funds, not the commercial banking sector, which

rarely serves this market.

16

As an MFIs interest and fee revenue covers

first its operating costs and then the cost of its

loanable funds, it may be considered to be

increasingly operating on a commercial basis.

MFI profitability enables expansion of operations

out of retained earnings or access to market-based

sources of funds. Operating as a for-profit, formal

financial institution may be the most complete

hallmark of MFI commercialization because this

implies subjectivity to prudential regulation and

supervision and that the MFI has become fully

integrated into the formal financial system.

However, MFIs strive for varying degrees of

commercialization; not all aim to become formal

financial institutions. This decision is usually

closely linked to a host of external factors

affecting the commercialization of microfinance,

discussed next.

Commercialization of the

Microfinance Industry

Commercialization of the microfinance

industry involves several factors including

the degree to which the policy environment

is conducive to the proliferation of commercial

MFIs, the extent to which the legal and regulatory

framework supports the development and growth

of commercial MFIs, the availability and access

of commercial MFIs to market-based sources

of funds, and the existence of key support

i nsti tuti ons. The mai n el ements of the

operating environment that determine the

commerci al i zati on of the mi crofi nance

industry can be divided into the following five

categories.

1. Policy Environment

Government policies that impede the

abi l i ty of MFIs to progress toward

commercialization (examples of such

policies are interest rate caps and selective,

ad hoc, debt-forgiveness programs).

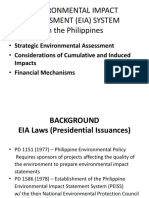

Figure 1.1: Attributes of MFI Commercialization

Progress Toward

Commercialization

Achievement of

operational

self-sufficiency

Achievement of

financial

self-sufficiency

Increased

cost-recovery

Utilization of

market-based

sources of funds

Full Commercialization Applying Commercial Principles

Operation as a

for-profit MFI as

part of the formal

financial system

COMMLPC|AL|ZAT|ON OP M|CPOP|NANCL: |NDONLS|A

4

Subsidized (government or donor-

supported) microcredit programs that may

inhibit the development and growth of

commercial MFIs.

2. Legal Framework

The legal framework for secured transactions

(the creation [legal definition], perfection

[registration], and repossession [enforcement]

of claims) as well as for microenterprise

formation and growth.

17

The licensing options available to new MFI

entrants or semiformal MFIs interested in

transforming into formal financial institutions.

3. Regulation and Supervision

The prudential regulations and supervision

practices that govern MFIs mobilizing

voluntary public deposits specifically or

financial institutions in the broader financial

markets generally, and the institutional

capacity of the regulating body to carry out

its mandate effectively.

4. Money Markets and Capital Markets

Availability and access of MFIs to

commercial sources of funds, such as

nonsubsidized loans, from apex organizations

(wholesale lending institutions) or banks;

mobilization of voluntary savings, private

investment funds, or other market-based

funding sources.

5. Support Institutions

Existence of credit information collection

and reporting services, such as credit

information bureaus and credit rating

agencies, that capture information useful to