Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Articolo Seductive Bodies. The Glamour of Death Between Myth and Tourism-Libre

Uploaded by

TenaLeko0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

33 views28 pagesA travelling exhibition of "real human bodies" is haunting european cities. The bodies of the deceased erase the boundary-line between culture and nature, art and life, vision and eyesight. This is due to a collection of anatomical specimens, produced and preserved according to a newprocess developed by Gunther von Hagens.

Original Description:

Original Title

Articolo Seductive Bodies. the Glamour of Death Between Myth and Tourism-libre

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentA travelling exhibition of "real human bodies" is haunting european cities. The bodies of the deceased erase the boundary-line between culture and nature, art and life, vision and eyesight. This is due to a collection of anatomical specimens, produced and preserved according to a newprocess developed by Gunther von Hagens.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

33 views28 pagesArticolo Seductive Bodies. The Glamour of Death Between Myth and Tourism-Libre

Uploaded by

TenaLekoA travelling exhibition of "real human bodies" is haunting european cities. The bodies of the deceased erase the boundary-line between culture and nature, art and life, vision and eyesight. This is due to a collection of anatomical specimens, produced and preserved according to a newprocess developed by Gunther von Hagens.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 28

Seductive Bodies:

the Glamour of Death

between Myth and Tourism

MARXIANO MELOTTI

Marxiano Melotti

Abstract

The discovery of the mummy of Tutankhamun, one of the first great me-

dia events of archaeology, as well as the success of tzi, advertised treasure

of the Museum of Bolzano, or the ever green fascination of the anatomical

machines due to the Prince of Sansevero show an interesting aspect of the

tourism and society. Western culture seems to be invaded by the tourist cult

of death. Even the bodies of the victims of Pompeii, actually mere casts giv-

ing shape to the void, have been essential for the tourist success of the site,

as well as the pilgrimage to the uncorrupted corpse of Padre Pio, actually

covered by a silicon mask created by the experts of Madame Tussauds Mu-

seum, show some cultural dynamics where artefact prevails on reality, the

nothing over the object and emotion over the content. The global success

of the exhibitions Body Worlds, which display real human bodies, invites

us to reflect on the historical path of the musealisation of death and, in a

broader sense, of some dynamics of the present liquid society, where edu-

cation and entertainment, tourism and market, culture and leisure intertwine

and hybridize.

Seductive Bodies: the Glamour of the Death between Myth and Tourism

*

The bodies of the deceased erase the boundary-line between culture

and nature, art and life, vision and eyesight.

Seamus Heaney

1

In search of the otherness

Spectres, or rather corps, are haunting Europe. This is due to a travelling

exhibition: Body Worlds. The Original Exhibition of Real Human Bodies.

It displays, as one of the editors of its catalogue explains, something unusual:

anatomical specimens, produced and preserved according to a newprocess de-

veloped by Gunther von Hagens

2

. This collection, shown for the first time in

Germany in 1997, has increasingly expanded over the years and has become

a true mass phenomenon, with exhibitions simultaneously held in different

towns and hundreds of thousands of visitors all over the world

3

. The show, of

course, step by step, has received enthusiastic acceptance and vehement re-

jection: its undoubted educational value it teaches to overcome the taboo of

death and to better understand and treat our bodies is accompanied by a spec-

102

CRITICAL MATTERS

tacularization of death and, more

specifically, of the human bodies,

which should make us reflect on

the relationship of our society with

death.

But is it really necessary to

overcome this taboo? or, as also

the success of this exhibition

shows, has our society already sub-

stantially overcome it and, thanks

to the continuous bombardment of

strong images in films and televi-

sion, has become able to live death as an entertainment with a leisure dimen-

sion of cultural and tourist character? And, if so, does it really make sense en-

joying ourselves with death?

The death tourism has already developed on such a scale that some schol-

ars have even coined a term, dark tourism, to describe the tourist experiences

that, in various ways, have to do with death or, in a broader sense, with pain

4

:

visits to battlefields and concentration camps and trips to sites of natural dis-

asters or murders, not to mention some more sophisticated forms, apparently

not directly related to death, involving tours to places of extreme poverty or

danger, such as the favelas or some underground missile bases. Their common

denominator is the desire of seeing death: they are places that have hosted

or are hosting it or may cause it. Of course, in the history of the European cul-

ture, the world of death and the dead tends to be taboo: we get rid of the dead

bodies in a hurry, we relegate them in special places, we perform rites to give

sense to the detachment between the living and the dead and, above all, to de-

fine a clear and possibly insurmountable barrier between the two worlds.

However, also the exact opposite is true. In the Western world the death and

the dead have always been next to the living, and, in spite of what was said in

the presentation of von Hagens exhibition, seeing death or the dead is not at

all unusual, even in tourist activities. We can even say that tourism was born

with the death not only in metaphorical terms travelling to see beyond but

also in concrete terms: the ancient visited the shrines and tombs of heroes, just

like the grand tourists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries visited graves,

cemeteries and funerary monuments and the modern tourists continue to do.

Archaeological museums exhibit objects mostly coming from funerary en-

Marxiano Melotti

103

CRITICAL MATTERS

Dead bodies as a show: the exhibition Body Worlds

(Rome, 2012)

dowment and the archaeologi-

cal sites are, very often, traces

of places that no longer exist.

The archaeological and cul-

tural tourism are essentially

death tourism.

The same thing may be said

for the bodies of the past.

Von Hagen uses a technique

certainly rather innovative and

stages the bodies in a new

way, in athletic and extremely

vital attitudes that, by reversing the cultural image of the still and composed

dead body, can leave the public dazed. However, Europe, since medieval

times, is accustomed to interact with the mummified bodies of the Saints and,

as the success of the exhibitions of Padre Pios corpse shows, still has a great

interest in these practices. Similarly, the modern discovery of ancient Egypt

at the end of the eighteenth century introduced the Egyptian mummies into our

imagery, making them protagonists in exhibitions and museums. We might

even assert that exactly the collections of these mummies have popularized

some important museums.

Gunther von Hagen, however, goes further. His plastinated bodies lead

us into the heart of a more recent phenomenon, edutainment, i.e. the inter-

connection of education and entertainment: one of the most interesting aspects

of the post-modern culture. Von Hagen in fact organizes exhibitions, i.e. cul-

tural events of traditional character and traditionally oriented to education that

are also shows, belonging to the complex media dimension of contemporary

society. His bodies, without skin and with muscles, bones and internal organs

exposed, plastically modeled while playing a guitar, kicking a ball or playing

cards, make show. The body of a pregnant woman with the foetus inside it, as

well as the number of foetuses exhibited in their developmental order, are first

of all a show, which arouses discussions and debates affecting some of the

most delicate and controversial ethical, cultural and political issues, such as

abortion and euthanasia. And so they attract the public.

Similarly, the newspapers of the cities that temporarily house these exhi-

bitions, to tickle the public, highlight their most morbid and controversial as-

pects, with true or false notes. Hence the news that von Hagen for his creations

Marxiano Melotti

104

CRITICAL MATTERS

A tourist success. Egyptian Mummies in the British

Museum

would use corpses of executed Chinese or that, at his request, he would have

plastinated the corpse of Michael Jackson. It is the liquid culture of con-

temporary society, where history, ethical issues and gossip intertwine and hy-

bridize

5

. The post-modern aspect of these exhibitions was rightly pointed out

by a clever Italian observer, who has defined von Hagens commercial oper-

ation as an outlet of plastic resurrection

6

. In fact, von Hagen would have even

considered the possibility of selling plastinated anatomical parts as souvenirs.

Once more, culture, education and commercial aspects seem inseparable.

The success of the exhibition is definitely due to voyeurism: the morbid in-

terest in death that cultural tourism channels and makes socially acceptable.

But, paradoxically, such a museum display of the body reduces, if not can-

cels completely, the impact of the dark show. Von Hagens plastinated bod-

ies, with their labels and date of creation, become sculptures and eventually

loose their macabre otherness. All the more so, since the sophisticated tech-

nique of plastination adopted ends up making bodies so real that, according

to many visitors, they seem to be made in plastic. This is a paradox of the im-

age society, which takes the artifice as its model and nourish itself with un-

precedented forms of hybrid authenticity. In short, Von Hagen has created his

own fortune using edutainment as a mirror, but this mirror has eventually de-

stroyed the strength and uniqueness of its exhibitions, by assimilating them to

the usual models of traditional cultural and educational tourism.

But whence comes this interest in the world of death? The answer, as al-

ways, is to be found in the great classics. There-

fore, it is worth dwelling upon one of the found-

ing texts of the European culture, where we

find some basic elements of our imagery:

Homers Odyssey.

Ulysses, in the most dramatic moment of his

journey, had to visit the world of the dead. It

was the so-called nekuia ()

7

. After ten

years of travels to worlds unknown, always at

the borders of civilization, he must cross the last

threshold and visit the world of the dead. He

must see the dead and talk with them. It was the

only way to find his way and to return to his is-

land, his home and his wife; briefly, to return

completely to the civilized world.

Marxiano Melotti

105

CRITICAL MATTERS

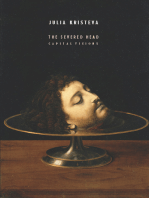

Body, Death and Tourism: the poster of

Body Worlds

The Odyssey, in fact, is the story of a grand rite of passage, where the en-

counter with distant peoples and monstrous creatures is a metaphor for the need

of all individuals to get in touch with the otherness to acquire knowledge, to

discover their own identity and to be eventually re-aggregated to their own world

with a newlevel of awareness and a newsocial role

8

. The poememphasizes the

importance of travel and contact with the otherness for knowledge.

Ulysses meets the Cyclops, Circe, the Sirens etc. But this is not enough to

let him regain his identity. He must make the extreme trip, he must pass the last

test. So he faces a partly real and partly dreamlike journey to the world of death.

The journey toward death, and in this case looking at it, is a fundamental rite

of passage with a strong identity value and an important educational meaning.

The death, the other side of our existence, completes the pre-existing knowl-

edge with that of the other world.

The trip is quite interesting. Ulysses meets souls that are both tangible and

intangible. They are ethereal and dreamlike creatures, but at the same time are

bodies that drink blood. Homer, in short, raises these questions: how to repre-

sent the contact with the dead? howto make it material a dreamlike experience?

This trip one of the first representations of the need of the living to interact

with the dead breaks a taboo. After death the bodies of the deceased get out

of our world and must remain outside it in order to give sense both to them-

selves and to us. The funeral is a ritual of detachment marking this separation.

The return of the dead represents the rupture of an order and of a balance.

The dead who return can only be ghosts or spirits to be exorcised or, in some

cases, extraordinary beings to be honoured and venerated or adored.

This is the case of the Christian religion. At its basis there is the return of

a body from the world of the dead: an exceptional and unrepeatable event that

testifies the both human and divine nature of that body and founds its cult.

Ulysses journey is also a metaphor and a model of an important ritual experi-

ence that European culture has always emphasized: the initiatory journey into the

other world, the search of contact with the beyond, which can take the formof a rite

of passage or, in our world, of tourism and, in particular, archaeological tourism.

Fromthis point of view, Gunther von Hagens exhibition may be considered the cul-

mination of a cultural experience inspired to a centuries-old collective need.

The relationship with death and with the bodies of the dead, however, en-

tails an ambiguous and conflicting relationship: it attracts and repels, it brings

an important knowledge but at the same time is dangerous and contaminant,

and therefore must be absolutely avoided or exorcised.

Marxiano Melotti

106

CRITICAL MATTERS

Mummies. From eternity to tourism

The presence of dead bodies in our world is conceivable only in quite spe-

cific forms. This is, in particular, the case of the mummies. The body of the de-

ceased is crystallized in a space between the worlds: it is in our world (you can

see it, you can touch it) but, at the same time, it is already in the afterlife.

Yet, in the Egyptian world this did not imply a reversal of the balance: the

body of the deceased remained materially and eternally present in the world,

but in a special space: the city of the dead, the cemetery, the grave dug in the

rock or, for the happy few, enclosed in inaccessible pyramids.

With the mummy there was a technical contact, when it was created, and

a ritual contact, when it was honoured and then locked up in its special space,

but there were no permanent experiential contacts.

Archaeology and tourism have somehow altered this relationship. When,

starting from the eighteenth century and with greater intensity between the end

of the nineteenth century and the twentieth century, French and English ar-

chaeologists began to dig and open the ancient tombs in Egypt, they re-

brought the mummified bodies to our world.

The success of the Egyptian civilization in popular culture owes much to

the mummies. Let us think about the tours in the early nineteenth-century

Britain of an Italian archaeologist and adventurer, Giovanni Battista Belzoni

9

:

together with treasures, relics and casts of works of art, he brought with him

some mummies, which attracted a huge crowd. Ancient Egypt was soon re-

thought and defined as the mysterious

civilization of death.

Obviously, these findings were im-

pressive for their deep symbolic value.

After two or three thousand years,

through the dead we could go back in

contact with the living of that time.

These bodies created a sort of direct

channel with the culture of the ancient

Egypt and, in particular, with its people,

regarded as an alive whole of men,

women and children: something much

stronger than a contact through other ar-

chaeological finds.

Of course, even in this new use, the

Marxiano Melotti

107

CRITICAL MATTERS

A new business. Mummies for sale

mummies have maintained their primary function of powerful communication

tools between the worlds (in this case between the modern world and the an-

cient world), but in our secularized age they have lost their ritual function and

have entered the new contexts of science, museums and tourism. From sub-

jects of a ritual existence inside the tomb, they have become serial objects

of scientific research and tourist gaze.

On the other hand, in our world, even the emotional relationship remains

stuck and neutralized in a dimension of aesthetic use, in museums or tourist ac-

tivities. Moreover, the mummification itself involves a process of transfor-

mation of the body of the deceased into a sort of monument, and this changes

its status. The mummified body appears frozen in time and becomes alien to

the transformations that affect the existence of the living.

The mummified body, in our culture, becomes a sort of work of art, a mon-

ument to the otherness, which, acquiring the harmless traits of the archaeo-

logical finds and historical evidence, fascinates and perhaps inspires some fears,

but in fact does not really frighten.

This special neutral relationship that we have established with the mum-

mies (which move between fascination and repulsion, acceptance and rejection,

but are firmly inserted in paths of aesthetic enjoyment in museums and tourism)

is endangered by the return of the ritual dimension in the new multicultural so-

ciety. An example: the mummified bodies of so-called primitive people,

which are displayed in our museums or

come to light during new excavations,

more and more often are claimed by the

members of those populations as bod-

ies and persons and are no longer re-

garded only as anthropological docu-

ments or archaeological finds

10

. In these

cases, the old cultural constructions that

have led us to neutralize the symbolic

value of the corpses and to accept them

as social objects, even usable in leisure

contexts, suddenly vanish and let us to

rediscover the taboo of death and to

feel horror for their display in museums

and tourist use.

An important moment in the

Marxiano Melotti

108

CRITICAL MATTERS

The birth of a myth. Howard Carter in the tomb

of Tutankhamun

process of tourist reinvention of

death was certainly the discov-

ery in 1922 of the Tomb of Tu-

tankhamen by Howard Carter.

This tomb, with its magnificent

treasures and its rich sarcophagi,

immediately exerted a disruptive

effect on the collective imagery

11

.

Within a few weeks that tomb be-

came object of tourist pilgrim-

ages, which obliged Carter to sus-

pend his excavations. A series of

accidents and fatalities that accompanied the works started the myth of the

Curse of Tutankhamen, due to one of the first campaign of media marketing

a myth which, after a century, is still periodically fed by entertainment lit-

erature, films and television programmes and does not seem to lose its ef-

fectiveness

12

. Since then, the popular image of Egypt is linked to the world

of mummies and sarcophagi and to their supposed magical power a sort of

modern, secularized version, due to media and tourism, of the symbolic and

ritual power of the dead in the ancient world.

But we must avoid the mistake of thinking about a modern world over-

whelmed by the myth of Tut and the magic of the Egyptian mummies. For a long

while tens of thousands mummies were used in British houses as low-cost fuel.

In fact, there is an interesting dualism: on the one hand, the fascination for the

world of death and the transformation of the bodies into museum pieces, with

media coverage of the mummies as a channel of communication with the past;

and, on the other hand, the detachment and estrangement fromthese mummies,

if not the suspicion and contempt for them. This clearly shows that the myth of

the mummies is a cultural construction with specific functions, which works only

in certain contexts of aesthetic, educational and museum use.

We are now in a new space: that of tourism, where some symbolic and ex-

periential elements of the traditional and religious culture persist (such as the

rites of passage and the search for the otherness), but other elements have

vanished or were weakened and placed in a new leisure context.

The dark side of the Enlightenment

In the history of the use and display of the human body, we must recall the

Marxiano Melotti

109

CRITICAL MATTERS

The birth of a myth. Howard Carter in the tomb of

Tutankhamun

Prince of Sansevero, whose anatomical machines are sometimes mentioned

as illustrious antecedents of Von Hagens work.

He lived in Naples, which, thirty years before the French Revolution, was

a culturally vibrant town, in spite of its contradictions. As for the issue con-

cerned, then Naples had a very special relationship with the world of death and

spirits and was pervaded by cults, beliefs and superstitions (which in part per-

sist) linked to the dead and their mortal remains.

The Prince was a typical exponent of the cultured aristocracy of the late

eighteenth century: a pre-Enlightenment intellectual, an alchemist, a Mason,

a Rosicrucian, almost totally immersed in a magical-scientific atmosphere

13

.

Now all this may appear ridiculous, but then it seemed to be dangerously rev-

olutionary. But, first and foremost, he was an inventor, who is still remembered

for his useless inventions, such as the blue colour for the fireworks and a

floating horse-drawn coach. Anyhow, he was one of the first researchers in-

terested in leisure, amusement and entertainment.

In 1763, with the help of an anatomist, Giuseppe Salerno, he created two

anatomical machines: two human bodies, a male and a female, with an ap-

parently intact circulatory system, which, according to some people, he ob-

tained with a technique somehow similar to Von Hagens. Near the body of the

woman originally there was even a small body of a foetus, still attached to

the placenta through the umbilical cord. In fact, Von Hagens was not the first

to pay a particular attention to the female body and motherhood, combining sci-

entific curiosity and voyeurism.

These machines were impressive creatures,

without a clear status (skeletons, mummies,

sculptures?). Their use was primarily aesthetic,

satisfying the intellectual pleasure of artifice and

technique. However they were also a scientific

challenge to faith. In a context that had begun to

become secularized, Sansevero gave a secular

answer to the Catholic worship of relics.

Obviously, these two creations had a strong

impact on the collective imagery; all the more so

because (unlike the Christian relics and the Egypt-

ian mummies) they did not come from an un-

known elsewhere in space and time, but froma lab-

oratory situated in the city, in the basement of a

Marxiano Melotti

110

CRITICAL MATTERS

An "anatomical machine" created

by the Prince of Sansevero

patrician palace.

Sansevero, disliked by the Church, was accused of creating these two ma-

chines by injecting a metalizing substance in bodies still living. In addition, the

popular voice blamed him for using them in his magic and Masonic rituals.

With these allegations the two machines got out of the area of scientific ex-

periments to become judicial evidence of a supposed double murder and were

relocated within the traditional area of religious and magic practices. Europe

was not yet ready to accept a use of death for merely recreational and aesthetic

purposes.

The casts and the invention of Pompeii

From this point of view, it is quite interesting what then began to happen

in the nearby Pompeii. As well-known, this ancient Roman town was buried

by an eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. After centuries of neglect, its remains

were identified in the eighteenth century and in 1748 the excavations began.

During them, the remains of the victims of that eruption came to light period-

ically and this started an interesting process of popular and media reinvention

14

.

It is worth recalling the discovery in 1768 of the remains of eighteen bod-

ies. One of them was immediately presented by the press as a wealthy Roman

matron, killed by the eruption while she was secluded with a gladiator, her se-

cret lover.

This combination of love and death and archaeology and gossip was im-

mediately successful and drew the attention of the general public. To the fas-

cination for death, which, as we have already said, has a profound initiatory

value, it added an element of erotic character, which helped to make the con-

tact with the world of death even more attractive.

Also voyeurism played an important role. We can recall a significant ex-

ample: in 1772 the remains of a female body and the shape of the ash and lapilli

compressed where once there was her breast suggested to cut the ground and

to make a mould of it. This strange object was placed in a museum. Its intrin-

sically morbid significance was clearly showed in 1852 by a French writer,

Thophile Gautier. In one of his tales, he gave a name to that body, Arria Mar-

cella, and imagined the story of a tourist who visited the museum and, excited

by that breast, felled in love with the non-existent girl and travelled to Pom-

peii in search of her, between dream and reality, body and ghost

15

.

In 1863, in Italy, which two years before had become a kingdom of re-

spectable extension thanks to the annexation of the former Kingdom of the Two

Marxiano Melotti

111

CRITICAL MATTERS

Sicilies, including the area of Pom-

peii, the new director of the excava-

tions, Giuseppe Fiorelli, recreated the

archaeological site of Pompeii and

transformed it into a site of tourist

interest with the introduction of an

admission fee. Moreover, he divided

the archaeological area into blocks

and attributed unambiguous names to

their streets and houses, giving it the

form of a museum-city. The open

area, which was placed in spatial con-

tinuity with the surrounding country-

side and was romantically endowed

with ruins in permanent excavation,

became a real site: a symbolically

closed and special space allowing the magical and initiatory contact with the

world of death and with the past, of course after the payment of a bourgeois

ticket.

This innovation marks the transition of the area from the Grand Tour of the

pre-Romantic and Romantic age to the modern cultural tourism. Fiorelli gave

the newly united Italy a large archaeological site of great national and identity

interest. But, of course, that good intention had to be followed by some con-

crete outcomes. Realizing that the peculiarity of Pompeii was its special rela-

tionship with death and, above all, the way travellers, poets and scholars rep-

resented the area, he thought to nurture this collective idea of Pompeii with

new and even more intriguing images. Thus he instrumentally introduced his

casts, well aware of their impact on tourism. He had the intuition of representing

death in a space which was already partially based on represented authen-

ticity. In fact, he transformed the site into a museum of death, by crystallizing

its image in that of a large crypt. This made Pompeii a real city of death: an

operation where the images of the bodies have played a key role.

This voyeuristic tension of tourism or, rather, of society, but grasped and

channelled by tourism in a special way is a constitutive element of our pres-

ent. Perhaps, the most telling examples of this relationship are exactly the Pom-

peii bodies: the casts, which, according to the collective construction con-

solidated in the last two centuries, we are used to consider as the bodies of its

Marxiano Melotti

112

CRITICAL MATTERS

The fascination of death. Casts in the archaeo-

logical site of Pompeii

ancient inhabitants. The success of Pompeii in the collective imagery largely

depends on these strange objects. But they are not bodies: they are neither

corpses nor mummies. They are simply casts obtained by filling the vacuum

left by the bodies buried by the volcano ash and lapilli and later decomposed

in the ground

16

. These casts, often of twisted and disquieting shapes, which

seem to have fixed in a timeless dimension men, women, children and animals

in their desperate struggle against death, are artefacts due to the imagination

and to the subtle entrepreneurial spirit of an archaeologist.

The highly dramatic aspect of the casts, which immediately entered the pub-

lic image of Pompeii, was due to the contraction of the muscles caused by the

very high temperature of the ash cloud that invested the bodies

17

. However, we

must not underestimate Fiorellis operation, which was attentively built pay-

ing great attention to media and tourism: something that today appears quite

normal and would go unnoticed, since we are totally accustomed to this kind

of use of the darkest interests of tourism by advertising and even cultural mar-

keting.

Among the first casts made in 1863 there was one of a female body, found

with a silver ring and gold earrings, which soon acquired fame as a prostitute

or, because of the effect on the belly of what has been interpreted as the skirt

gathered up about the hips, as the pregnant woman. So, the same cast ac-

quired a strong identity in the collective imagery, now responding to the titil-

lating model of the Arria Marcellas sensual breast and now proceeding in the

wake of the gloomy pregnant body created by Sansevero. In the 1875 the preg-

nant woman disappeared and was substituted by the cast of a young and beau-

tiful victim of the eruption, as was defined by the famous Italian archaeolo-

gist Amedeo Maiuri

18

. As

has been noticed, novelty

and physical beauty be-

came the keys to the pop-

ularity of the casts, which

define a new era in the

history of the interpreta-

tions of Pompeii

19

.

The apparent bodies

actually are masks of the

vacuum or, if you prefer,

masks of death. Techni-

Marxiano Melotti

113

CRITICAL MATTERS

The musealisation of the bodies. Cast in the Antiquarium of

Pompeii. Photo by G. Sommier (1834-1914)

cally, however, in spite of the attention that has been paid to them and their dis-

play in museums, they are not archaeological finds. They are the visualization

of what we want to see, when going into an archaeological site. They are ex-

pression of our desire of contact with death, of our voyeuristic tension and of

a subtle form of sublimated necrophilia, which have transformed the non-finds

into bodies. They are, at the same time, real and non-real, present and absent:

virtual images of the body and death, which, in spite of their immaterial ori-

gin, are terribly concrete

20

.

This form of relative authenticity is an example of hybrid identity in

which the body, nothingness, mask, real and virtual objects coexist and appear

inseparable.

What are the bodies of Pompeii? And why we have shaped them? They are

masks of death, which satisfy our fantasies and our need to see beyond and to

have contact with the afterlife world.

Bodies in Tour

Outside the site, people that the mass media have increasingly accustomed

to see the death, need much more. Thus the world-wide travelling exhibitions

of the bodies of Pompeii, to regain attraction, must use special effects. In the

Archaeological Museum of Naples, where one of these travelling exhibitions

started its tour, the tourists were greeted by a tremor intended to suggest the

sound of an eruption and to create an empathic anxiety for the impending

tragedy, which actually had taken place almost two thousand years before.

In contrast, in Chicago the local organizers chose to emphasize not so much

the image of human bodies, but rather that of a dog still tied, abandoned by the

owner (at least according to the popular myth-making) and mummified in

the lapilli. If the autopsy vision of what seems to be a human corpse can be so

strong as to scare or, on the contrary, so banal as to loose its interest, the sight

of a helpless little dog always works. The pet society of the contemporary

affluent Western world is readily moved by an animal, while it is often much

colder and more distrustful in the case of a human, whose death could raise a

troublesome sense of guilt.

In New York, in 2011, the humans returned to be protagonists in a show-

style exhibition (Pompeii: Life and Death in the Shadow of Vesuvius). Vis-

itors, after watching interesting but harmless everyday objects, were wel-

comed and closed in a tight dark space, a real decantation chamber, where,

among the plays of light, sound effects and tremors, were initiated into the most

Marxiano Melotti

114

CRITICAL MATTERS

tragic secrets of the dead

town, to be admitted af-

terwards to the special

world of the next room.

Here, in an atmosphere of

suffused light and sounds,

they could see the bodies,

sculpturally lying on

podiums apparently

pending in a scattered

way. The death and its

masks appeared in a

seemingly hyper-emo-

tional and experiential

way, which was however

rather anaesthetized. In

fact, masks, casts and

bodies became sculp-

tures, deserving aesthetic

enjoyment. But we are in

a post-modern society,

where even the concept

(and the experience) of

authenticity has under-

gone a deep process of re-

definition. In order to cre-

ate a stronger and more

immersive emotional at-

mosphere, the organiser needed a great number of bodies and, probably for the

impossibility of displaying a large number of original casts, filled the room

of new casts, which were casts of casts. This way the public, in search of dark

emotions, received its sacrifice offering. The most interesting aspect of the

whole exhibition was probably the location: not a traditional museum, but an

event space, Discovery Times Square, where, together with the archaeologi-

cal exhibition on Pompeii, hosted an exhibition on Henry Potter, the hero of

the renowned series of novels and movies presenting a different but equally

effective kind of contact with the otherness. Today the lure of dead is a pop-

Marxiano Melotti

115

CRITICAL MATTERS

Emotional tourism. Casts of victims of Vesuvius eruption in

Pompeii

The emotional gaze. Cast of a dog in Pompeii. Photo by G.

Sommier (ca. 1874)

ular diversion, which

can assume different

shapes: the liquidity

of present society, in

which many phenomena

tend to lose their bound-

aries and seemto merge,

produces a range of new

indefinite experiences

where culture and mer-

chandising, history and

romance, reality and at-

mosphere, death and art are mixed and variously interconnected. In this new

frame the magic word is edutainment, the liquid connector linking education

and entertainment.

If the artistic sublimation transforms bodies and casts into sculptures and

makes the masks objects and findings, we can say that the imaginative

process of moulding and masking of nothing started by Fiorelli has found its

followers, inspired by the visceral post-modern need of going beyond. Fiorellis

technique has recently been replaced by another one, involving the use of trans-

parent resins. This allows us to see inside the mass that gives consistency to

the vacuum and to observe the world of death even more closely and to catch

a glimpse of the intimate nature of what each mask hides: skeletons, bones and

skulls. The interest shown by the public for this technique is indicative of a cul-

tural transformation: the visual habit to death somehow makes less effective

and less interesting the contact with the cast that, for its sculptural aspect, can

be decoded as a simple sculpture. In other words, the audience, which is already

educated by movies and television news and shows with a strong voyeuristic

orientation, looks for something more. Here even archaeology absorbs the CSI

model and offers the visitor of museums and the consumer of cultural products

experience of forensic laboratory. We enter into the cast and see the bones, or

to return to the mummy of Tutankhamun, on live television we submit the

corpse of a pharaoh died thousands of years ago to TAC and analyses of

forensic pathology worthy of a TV show, in order to solve the riddle of a mys-

terious death and, perhaps, to find a murderer.

This is also the media-oriented setting deliberately implemented by the Mu-

seum of Bolzano, in order to maintain the success of the mummy of tzi, the

Marxiano Melotti

116

CRITICAL MATTERS

The Mummy goes to the doctor. Analyses on the body of tzi

man from ice (according to the official definition approved by the Province),

one of the worlds most famous human remains, comparable to the well-

known mummies of ancient Egypt

21

. The body of this Copper-Age hunter,

merchant, metal seeker, shaman-and headman (according to the elastic inter-

pretation by the curators of the Museum), dead perhaps murdered more than

4,000 years ago among the ices of the Schnalstal and found in 1991, is at the

centre of an exciting scientific research that since the beginning, thanks to the

press, has become fictional. The mummy underwent deep and well-publicized

analyses and the visitors of the Archaeological Museum can see the video en-

doscopy and relive the exciting journey inside the mummy

22

. After an inter-

national tour, the mummy now rests in the Museum that exhibits it, as the gem

of its collection, in a particular cold store, with a small and elegant window,

which allows visitors to peep inside

23

. Actually, it is only a special show-

case, but it entails an estranging effect. The design recalls a furnace and gives

the impression of looking at a dead body in the process of cremation. In short,

even in this case, the cultural use of the past moves ambiguously between ed-

ucation and entertainment, bordering necrophiliac voyeurism.

The Sleeping Beauty

Another interesting case is the Capuchin Crypt in Palermo: an incredible un-

derground space, created in the late sixteenth century, which houses eight thou-

sand mummified bodies: men, women and children; standing and lying; fully

dressed and divided according to their gender and social class.

This cemetery lies beneath a church. We are therefore in a religious and fu-

nerary context, where the presence and contemplation of death is not surpris-

ing. The relatives of the deceased and the believers could go down to these cat-

acombs to implement their nekuia.

As in Pompeii, the coming of tourism changed the situation. The bodies of

the crypt became one of the most famous spots of the Grand Tour. But the

tourist gaze of the secularized travellers changed the meaning of those

mummies, which, at least for them, were only a macabre show.

Once more here we see the usual dynamics: cultural tourism, in contact with

death, implements its intrinsic initiatory value, but, at the same time, it acts as

a socially acceptable pretext for satisfying voyeurism.

In the same years when in Pompeii some special creations became fa-

mous, in Palermo there was the creation of the mummy of a two-years-old

Marxiano Melotti

117

CRITICAL MATTERS

young girl, Rosalia Lombardo, who died of pneumonia in 1920.

Thanks to a special technique (which was identified only in 2009) an em-

balmer, Alfredo Salata, created an extraordinary image: a sort of doll, soon

dubbed The Sleeping Beauty. Its success was amazing and it became object

of a macabre pilgrimage, where faith and tourism, as well as morbidity and af-

fection, were indistinguishable. The same nickname given to this body, of

which we have now only the head, is extremely significant. The reference to

the world of fairy tales attenuates the deep meaning of this macabre voyeurism

and somehow makes it more acceptable: looking at the embalmed head of the

little girl becomes like listening to a fairy tale. On the other hand, the reference

to the fairy tales, which often have the same structure as the initiatory tales,

where the heroes face adventures taking them temporarily in another world, ac-

tivates the initiatory mechanism of nekuia. The body of the Sleeping Beauty,

uniting sleep and death, takes us into the other world, from which, however,

at the end of the visit, we can awaken.

The Silicon Saint

In Italy, the main centre of the Roman Catholic culture, the cult of the saints

and the relics is very important and has a long-standing history

24

. It is interesting

to see the change that this cult has recently undergone. Even faith has been in-

corporated into some typical processes of contemporary post-modern society:

the construction of forms of relative authenticity and hybrid identities, the

research of media coverage with its effects, and the transformation of many ex-

Marxiano Melotti

118

CRITICAL MATTERS

Morbid gaze between faith and tourism. The Capuchin Crypt in Palermo

periences into tourist ac-

tivities.

An incisive example

of this process is the cult

of Padre Pio (Father

Pius), a Capuchin friar

who lived in Southern

Italy in the last century

and was beatified in

1999 and canonized in

2002. Some years later,

in 2008, on the occasion

of the public exposition of his body (an event that had a world-wide TV cov-

erage), the organizers decided to show the face of Padre Pio or, rather, some-

thing similar to it. Really, what could be seen was its mask: precisely, according

to the official records, a thin flesh-coloured silicone mask.

Of course this choice aroused many ironies as well as lively disputes. An

Irish blogger, for example, entitled his comment Padre Pio, the Silicon Saint

and came to write that his mask was only a rubber Halloween mask

25

. Crit-

icisms came even from some declared faithful of Padre Pio. In his blog an Ital-

ian believer wrote: Of the holy friars body we will not see even a shred of

flesh (...). We want to see it at all costs. But who decides (for us) have stated

that we must see nothing

26

. The protest in this case was not so much against

the mask as against the concealment of the body.

The invisible mask located on the face of Padre Pio gave authenticity to

the experience: it prevented us from seeing the real face, creating a barrier

with reality, but it putted us in touch with the world of death, allowing us to

see it. The fact that the official site carefully specifies that the mask was thin

reveals a latent embarrassment for this mix of nature and nurture (in this case,

of technology) and between the sacred and the profane

27

.

At the same time it also suggests the symbolic function of passage of the

mask: regardless of its material, it allows us to look beyond. However, even

here we face a hybrid reality: paradoxically, the artificial mask gives identity

and authenticity to a real body. As we grasp from the newspapers that have cov-

ered the event, the believers were stricken by the rosy colour and by the vi-

tal look of the face, interpreted as evidence of holiness, although due only to

the mask.

Marxiano Melotti

119

CRITICAL MATTERS

The silicon Saint. The mask of Padre Pio

A particular reflection deserves the use of silicone. Beyond its instrumen-

tal use due to its well-known qualities, we cannot forget its symbolic value in

the present society. The industry of beauty, connected with the new culture of

wellness, has largely built its fortunes on this substance.

One of the most interesting aspects of this operation is the company en-

trusted with the mask: Madame Tussauds Museum. This brings us back to the

heart of the society of reproduction and virtual reality already treated by Ben-

jamin and Baudrillard

28

.

The Church, to affirm the authenticity of the body exposed, turned to a

wax museum, using the tools of the culture of leisure and entertainment. With

the intention of stressing the uniqueness of the Saints body, it actually created

the conditions for its multiplication. In fact, simulacra of Padre Pio are now

housed in many wax museums, where they appear to be more authentic or, at

least, less fake, since each copy carries the same mask as the original. More-

over, we must recall that Padre Pio is not only an object of popular worship;

he is also a hero of contemporary media culture and, thanks to quite consid-

erable financial investments, the village where he lived, San Giovanni Rotondo,

has been transformed into a powerful attraction for tourism, with all its induced

activities.

A different model

In our society the widespread consumption of films and television pro-

grammes has led us to metabolize the view of death, blood and violence. We

live in a state of anaesthetized horror in which the macabre is news, show

and even marketing tool. Horror only lasts for the short time allowed by the

television news.

We have learned to live together with the most shocking images thanks to

a new aesthetic of death that exorcises them.

Let us think at the bodies falling or diving from the Twin Towers on 9/11,

at charred bodies of the American soldiers burned on the Baghdad bridge, at

the bodies of the victims of the tsunami, floating on the sea, decomposed and

inflated by water and putrefaction: all images published full-page in the news-

papers and transmitted and re-transmitted by television

29

.

But there is another way of representing the horror, which is perhaps even

more effective: absence. In a society based on the images and an aesthetic cult

of the body, absence of images and lack of bodies create anxiety and fear.

This is the case of the concentration camps turned into museums; this is the

Marxiano Melotti

120

CRITICAL MATTERS

case of the Holocaust

museums, where the

presence of absence is

overwhelming and dis-

quieting and the bodies

of the victims are pres-

ent in their absence. Ob-

jects, photographs,

spaces become signs

and metaphor of the

missing bodies. Once

more, we find a sort of

nekuia: an initiatory

journey into the world

of death.

A quite peculiar case is the 921 Earthquake Museum of Taiwan. In 1999 a

terrible earthquake devastated the island, destroying roads, buildings and

schools. The government decided to transform one of the schools destroyed into

a museum. Memory, mourning, prevention, education and tourism are here

closely intertwined, in an interesting experiment of serious edutainment.

In that school there were no casualties. But the pillars shattered and the

school desks piled recall the tragedy and give material consistency to the ab-

sent bodies of the victims of any past and future earthquake.

This museum is a good example of an educational relationship with death

and disasters that responds quite well to the emotional needs of contemporary

society. It satisfies the morbid impulses that lurk in each of us. But, at the same

time, it teaches us without the usual sensationalism and cynicism of the mass

media to accept death and to respect the human body.

References

Baudrillard J., Simulacres et Simulation, Galile, Paris 1981.

Bauman Z., Liquid Modernity, Polity Press, Cambridge 2000.

Belzoni G.B., Narrative of the Operations and Recent Discoveries Within the

Pyramids, Temples, Tombs and Excavations in Egypt and Nubia and of a

Journey to the Coast of the Red Sea, in search of the ancient Berenice; and

another to the Oasis of Jupiter Ammon, John Murray, London 1820.

Marxiano Melotti

121

CRITICAL MATTERS

A school collapsed. Site of the 919 Earthquake Museum of

Taiwan

Benjamin W., Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzier-

barkeit, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a.M. 1955.

Bock, Padre Pio, the Silicon Saint, http://bocktherobber.com/2008/04/padre-

pio-the-silicon-saint (26/04/2008).

Brown M.F. and Bruchac M.M., Nagpra from the Middle Distance: Legal Puz-

zles and Unintended Consequences, in J.H. Merryman (ed.), Imperialism,

Art and Restitution, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Mass. 2006,

pp. 193-217.

Burns L., Gunther von Hagens Body Worlds: Selling beautiful education, in

The American Journal of Bioethics, 7, 4, 2007, pp. 12-23.

Cantarella E., Sopporta Cuore. La scelta di Ulisse, Feltrinelli, Milano, 2013.

Capecelatro G., Un sole nel labirinto. Storia e leggenda di Raimondo di San-

gro, Principe di Sansevero, Il Saggiatore, Milano 2000.

Chamberlain A.T. and Parker Pearson M., Earthly Remains. The History and

Science of Preserved Human Bodies, The British Museum Press, London

2001.

Dwyer E., Science or Morbid Curiosity? The Casts of Giuseppe Fiorelli and

the Last Days of Romantic Pompeii, in V.C. Gardner Coates and J.L. Seydl

(eds), Antiquity Recovered. The Legacy of Pompeii and Herculaneum, The

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2007, pp. 171-188.

Fleckinger A., tzi, lUomo venuto dal ghiaccio, Folio, Bolzano - Wien 2007.

Frayling C., The Face of Tutankhamun, Faber, London 1992.

Gardner Coates V.C., Lapatin K., Seydl J.L. (eds), The Last Days of Pompeii.

Decadence, Apocalypse, Resurrection, Getty Publications, Los Angeles

2012.

Hales S. and Paul J. (eds), Pompeii in the Public Imagination. From its Re-

discovery to Today, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2011.

Heaney S., The man and the bog, in B. Coles, J. Coles and M. Schou Jorgensen

(eds), Bog Bodies, Sacred Sites and Wetland Archaeology, Warp, Exeter

1999, pp. 3-6.

Jacobelli L., Introduction, in Th. Gautier, Arria Marcella. Ricordo di Pompei,

Flavius, Pompei 2007.

James T.G.H., Howard Carter: the Path to Tutankhamun, Kegan Paul, New

York 1992.

Kritz W., Foreword to G. von Hagens and A. Whalley (eds), Gunther von Ha-

gens Body Worlds. The Original Exhibition of Real Human Bodies, Arts

and Sciences, Heidelberg 2009.

Marxiano Melotti

122

CRITICAL MATTERS

Lennon J. and Foley M., Dark Tourism: The Attraction of Death and Disas-

ter, Continuum, London 2000.

Liveley K., Delusion and Dream in Thophile Gautiers Arria Marcella; Sou-

venir de Pompi, in S. Hales and J. Paul, Pompeii in the Public Imagina-

tion, q.v., pp. 105-117.

Maiuri A., Pompei. I nuovi scavi e la villa dei misteri, Libreria dello Stato,

Roma 1931.

Manseau P., Rag and Bone: A Journey Among the Worlds Holy Dead, St. Mar-

tins Press, New York 2010.

Marchant J., The Shadow King: The Bizarre Afterlife of King Tuts Mummy,

Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Mass. 2013.

Melotti M., I riti di passaggio, in Antichit classica, Garzanti, Milano 2000,

pp. 719-720.

Melotti M., Crossing Worlds: Space, Myths and Passage Rites in Ancient Greek

Culture, in K. Mustakallio et al. (eds), Hoping for Continuity. Childhood,

Education and Death in Antiquity and the Middle Ages, Acta Instituti Ro-

mani Finlandiae 33, Roma, 2005, pp. 203-241.

Melotti M., Il fascino indiscreto delle catastrofi. Impatto mitico e mediatico

dello tsunami sullimmaginario collettivo, in La Critica Sociologica,

158, 2006, pp. 88-107.

Melotti M., Nascita di un mito. Il turismo a Pompei tra amore e morte, in L.

Jacobelli (ed.), Pompei, la costruzione di un mito. Arte, letteratura e aned-

dotica nellimmagine turistica di Pompei, Bardi, Roma 2008, pp. 95-116.

Melotti M., Fantasie ibride. Il corpo e la maschera nella rete globale, in P.

Sisto, P. Totaro (eds), Il Carnevale e il Mediterraneo, Progedit, Bari 2010,

pp. 57-88.

Melotti M., The Plastic Venuses. Archaeological Tourismand Post-Modern So-

ciety, Cambridge Scholars, Newcastle 2011.

Nicoletti G., LIkea del post-mortem, La Stampa, 30/08/2011.

Ogden D., Greek and Roman Necromancy, Princeton University Press, Prince-

ton - Oxford 2001.

Pagano M., I calchi in archeologia: Ercolano e Pompei, in A. DAmbrosio,

P.G. Guzzo, M. Mastroroberto (eds), Storie di uneruzione. Pompei, Er-

colano, Oplontis, Electa, Milano 2003, pp. 120-125.

Page D.L., Folktales in Homers Odyssey, Harvard University Press, Cam-

bridge, Mass. 1973.

Sharpley R. and Stone P.R., Life, Death and Dark Tourism: Future Research

Marxiano Melotti

123

CRITICAL MATTERS

Directions and Concluding Comments, in R. Sharpley and P.R. Stone, The

Darker Side of Travel, q.v., 2009, pp. 247-251.

Sharpley R. and Stone P.R. (eds), The Darker Side of Travel. The Theory and

Practice of Dark Tourism, Channel View, Bristol 2009.

Simone, Padre Pio e la maschera di cera, in

http://popimmersion.blogspot.com/2008/04/padre-pio-e-la-mashera-di-

cera.html, April 2008.

Walter T., Body Worlds: Clinical detachment or anatomical awe?, in Soci-

ology of Health and Illness, 26, 4, 2004, pp. 464-488.

Zatterin M., Il gigante del Nilo. Storia e avventure del Grande Belzoni, Il

Mulino, Bologna 2008.

Marxiano Melotti studies the continuity and discontinuity between the an-

cient and the modern world, with special reference to the re-discovery and val-

orisation of the past in the contemporary societies and, particularly, in the me-

dia. The relationships between tourism, world heritage and cultural identity are

among his main interests. He works on the relationships between religious rites,

cultural memory and tourism.

He is professor of Sociology and History of Educational Processes at Nic-

col Cusano University of Human Sciences (Rome) and professor of Tourism

and Heritage in the Master of Bicocca University in Magodhoo (Maldives). He

was Visiting professor at the Universities of Tampere (Finland), Gandia

(Spain) and Viseu (Portugal) and professor in the International Master in Eco-

nomics and Administration of Cultural Heritage at the University of Catania.

He is also the Secretary General of the Foundation for the Italian Institute

of Human Sciences (SUM), which organizes cultural events, seminars and con-

ferences connected with cultural heritage and promotes the Observatory on the

Italian Culture.

Among his published works, there are the books The Plastic Venuses. Ar-

chaeological Tourism and Post-Modern Society (Cambridge Scholars, New-

castle 2011), Turismo archeologico (Bruno Mondadori, Milano 2008), Mediter-

raneo tra miti e turismo (Cuem, Milano 2007).

On these themes he gave lectures in Italy and other countries (the United

States, Australia, Brazil, China, Saudi Arabia, Germany, Spain, Finland, Por-

tugal, Greece and Monaco).

*

This essay elaborates the text of a lecture given in Helsinki in 2013 at Heureka, the

Marxiano Melotti

124

CRITICAL MATTERS

Finnish Science Centre, on the occasion of the exhibition Gunther von Hagens

Body Worlds. I thank Mikko Millikoski, Research Director of Eureka.

Notes

1

S. Heaney, The man and the bog, in B. Coles, J. Coles and M. Schou Jorgensen (eds),

Bog Bodies, Sacred Sites and Wetland Archaeology, Warp, Exeter 1999, pp. 3-6.

2

W. Kritz, Foreword to G. von Hagens and A. Whalley (eds), Gunther von Hagens

Body Worlds. The Original Exhibition of Real Human Bodies, Arts and Sciences,

Heidelberg 2009. You can see also the site www.bodyworlds.com.

3

On this exhibition see T. Walter, Body Worlds: Clinical detachment or anatomical

awe?, in Sociology of Health and Illness, 26, 4, 2004, pp. 464-488; L. Burns, Gun-

ther von Hagens Body Worlds: Selling beautiful education, in The American

Journal of Bioethics, 7, 4, 2007, pp. 12-23; R. Sharpley and P. Stone, Life, Death

and Dark Tourism: Future Research Directions and Concluding Comments, in R.

Sharpley and P.R. Stone, The Darker Side of Travel. The Theory and Practice of

Dark Tourism, Channel View, Bristol 2009, pp. 247-248.

4

On dark tourism see J. Lennon and M. Foley, Dark Tourism: The Attraction of

Death and Disaster, Continuum, London 2000; R. Sharpley and P.R. Stone, The

Darker Side of Travel. The Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism, Channel View,

Bristol 2009.

5

On the concept of liquid society see Z. Bauman, Liquid Modernity, Polity Press,

Cambridge 2000.

6

G. Nicoletti, LIkea del post-mortem, La Stampa, 30/08/2011.

7

Homer, Odyssey, book 11. On the ritual meaning of katabasis in ancient world see

D. Ogden, Greek and Roman Necromancy, Princeton University Press, Princeton and

Oxford 2001.

8

On the meaning of the contact with the otherness in Odyssey see D.L. Page, Folk-

tales in Homers Odyssey, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1973, and

E. Cantarella, Sopporta Cuore. La scelta di Ulisse, Feltrinelli, Milano 2013. On pas-

sage rites in the ancient world see M. Melotti, Crossing Worlds: Space, Myths and

Passage Rites in Ancient Greek Culture, in K. Mustakallio et al. (eds), Hoping for

Continuity. Childhood, Education and Death in Antiquity and the Middle Ages, Acta

Instituti Romani Finlandiae 33, Roma 2005, pp. 203-241; M. Melotti, I riti di pas-

saggio, in Antichit classica, Garzanti, Milano 2000, pp. 719-720.

9

G. B. Belzoni, Narrative of the Operations and Recent Discoveries Within the Pyr-

amids, Temples, Tombs and Excavations in Egypt and Nubia and of a Journey to the

Marxiano Melotti

125

CRITICAL MATTERS

Coast of the Red Sea, in search of the ancient Berenice; and another to the Oasis

of Jupiter Ammon, John Murray, London 1820; M. Zatterin, Il gigante del Nilo. Sto-

ria e avventure del Grande Belzoni, Il Mulino, Bologna 2008.

10

On the debate and redefinition of values connected to native artefacts see M.F.

Brown and M.M. Bruchac, Nagpra from the Middle Distance: Legal Puzzles and Un-

intended Consequences, in J.H. Merryman (ed.), Imperialism, Art and Restitution,

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Mass. 2006, pp. 193-217; and the chapter

The Ethics of Display and Ownership in A.T. Chamberlain, M. Parker Pearson,

Earthly Remains. The History and Science of Preserved Human Bodies, The British

Museum Press, London 2001, pp. 180-188.

11

M. Melotti, The Plastic Venuses. Archaeological Tourism and Post-Modern Soci-

ety, Cambridge Scholars, Newcastle 2011.

12

On the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun and on some aspects of the related

myth-making process see: T.G.H. James, Howard Carter: the Path to Tutankhamun,

Kegan Paul, New York 1992; C. Frayling, The Face of Tutankhamun, Faber, Lon-

don 1992; J. Marchant, The Shadow King: The Bizarre Afterlife of King Tuts

Mummy, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Mass. 2013.

13

On the intriguing figure of Sansevero see G. Capecelatro, Un sole nel labirinto. Sto-

ria e leggenda di Raimondo di Sangro, Principe di Sansevero, Il Saggiatore, Milano

2000.

14

On the myth-making of Pompeii and the role of death in this process see: M.

Melotti, Nascita di un mito. Il turismo a Pompei tra amore e morte, in L. Jacobelli

(ed.), Pompei, la costruzione di un mito. Arte, letteratura e aneddotica nellimmagine

turistica di Pompei, Bardi, Roma 2008, pp. 95-116; S. Hales and J. Paul (eds), Pom-

peii in the Public Imagination. From its Rediscovery to Today, Oxford University

Press, Oxford 2011; V.C. Gardner Coates, K. Lapatin, J.L. Seydl (eds), The Last Days

of Pompeii. Decadence, Apocalypse, Resurrection, Getty Publications, Los Ange-

les 2012.

15

L. Jacobelli, introduction to Th. Gautier, Arria Marcella. Ricordo di Pompei, Flav-

ius, Pompei 2007. See also K. Liveley, Delusion and Dream in Thophile Gautiers

Arria Marcella; Souvenir de Pompi, in S. Hales and J. Paul, Pompeii in the Pub-

lic Imagination, q.v., pp. 105-117.

16

On the casts in Pompeii: M. Pagano, I calchi in archeologia: Ercolano e Pompei,

in A. DAmbrosio, P.G. Guzzo, M. Mastroroberto (eds), Storie di uneruzione. Pom-

pei, Ercolano, Oplontis, Electa, Milano 2003, pp. 120-125; E. Dwyer, Science or

Morbid Curiosity? The Casts of Giuseppe Fiorelli and the Last Days of Romantic

Pompeii, in V.C. Gardner Coates and J.L. Seydl (eds), Antiquity Recovered. The

Marxiano Melotti

126

CRITICAL MATTERS

Legacy of Pompeii and Herculaneum, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles,

2007, pp. 171-188.

17

A.T. Chamberlain, M. Parker Pearson, Earthly Remains. q.v., pp. 150-153.

18

A. Maiuri, Pompei. I nuovi scavi e la villa dei misteri, Libreria dello Stato, Roma

1931.

19

E. Dwyer, Science or Morbid Curiosity?, q.v., p. 183.

20

M. Melotti, Fantasie ibride. Il corpo e la maschera nella rete globale, in P. Sisto,

P. Totaro (eds), Il Carnevale e il Mediterraneo, Progedit, Bari 2010, pp. 57-88.

21

These are the words of the President of the Ente Musei Provinciali dellAlto Adige

in the introduction Il fascino dellUomo venuto dal ghiaccio in the guidebook ed-

ited by the Bolzano Museum: A. Fleckinger, tzi, lUomo venuto dal ghiaccio, Fo-

lio, Bolzano - Wien 2007, p.7.

22

Ibidem, p. 39.

23

Ibidem, p. 106.

24

On cults of relics and bodies, see P. Manseau, Rag and Bone: A Journey Among the

Worlds Holy Dead, St. Martins Press, New York 2010.

25

Bock, Padre Pio, the Silicon Saint, http://bocktherobber.com/2008/04/padre-pio-the-

silicon-saint (26/04/2008).

26

Simone, Padre Pio e la maschera di cera, in

http://popimmersion.blogspot.com/2008/04/padre-pio-e-la-mashera-di-cera.html,

aprile 2008.

27

M. Melotti, Fantasie ibride, q.v.

28

W. Benjamin, Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit,

Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1955; J. Baudrillard, Simulacres et Simulation, Galile, Paris

1981.

29

On the voyeuristic character of the media coverage of this tragedy see M. Melotti,

Il fascino indiscreto delle catastrofi. Impatto mitico e mediatico dello tsunami sul-

limmaginario collettivo, in La Critica Sociologica, 158, 2006, pp. 88-107.

Marxiano Melotti

127

CRITICAL MATTERS

You might also like

- Gorey, Edward - The Curious SofaDocument36 pagesGorey, Edward - The Curious SofaEnrique Rubio60% (5)

- Opera and Armenians G BamDocument32 pagesOpera and Armenians G BamJonathan FernandezNo ratings yet

- CasablancaDocument127 pagesCasablancaEmílio Rafael Poletto100% (1)

- Visual ArtsDocument40 pagesVisual Artsricreis100% (2)

- Predictive Astrology A Practical Guide PDFDocument116 pagesPredictive Astrology A Practical Guide PDFvnrkakinada100% (1)

- Batwa Cultural Values ReportDocument58 pagesBatwa Cultural Values ReportTenaLekoNo ratings yet

- Why Does Art Matter? Intellect's Visual Arts SupplementDocument21 pagesWhy Does Art Matter? Intellect's Visual Arts SupplementIntellect Books100% (4)

- Les Mardis de Stephane MallarmeDocument75 pagesLes Mardis de Stephane Mallarmeclausbaro2No ratings yet

- Discover Magazine - February 2015 USADocument100 pagesDiscover Magazine - February 2015 USAazispn99100% (2)

- Auschwitz - Museum Interpretation and Darker Tourism - William F. S. MilesDocument4 pagesAuschwitz - Museum Interpretation and Darker Tourism - William F. S. MilesNikMurrayNo ratings yet

- 1-The Symbolism of The Skull in Vanitas PDFDocument18 pages1-The Symbolism of The Skull in Vanitas PDFAmbar CruzNo ratings yet

- Animism Volume I Book, Ed. Anselm FrankeDocument129 pagesAnimism Volume I Book, Ed. Anselm Frankeamf100% (5)

- Interpol LyricsDocument9 pagesInterpol LyricsTenaLekoNo ratings yet

- Linda Nochlin Imaginary OrientDocument15 pagesLinda Nochlin Imaginary OrientMax Mara100% (1)

- The Visual in Anthropology PDFDocument10 pagesThe Visual in Anthropology PDFŞeyma Can100% (1)

- Amigurumi CarouselDocument4 pagesAmigurumi CarouselCristina CristeaNo ratings yet

- Amigurumi CarouselDocument4 pagesAmigurumi CarouselCristina CristeaNo ratings yet

- Study - Id9996 - Tourism Worldwide Statista Dossier PDFDocument75 pagesStudy - Id9996 - Tourism Worldwide Statista Dossier PDFkabir sacranieNo ratings yet

- AnanikDocument168 pagesAnanikTenaLeko100% (1)

- Dynamic 1Document16 pagesDynamic 1TenaLekoNo ratings yet

- Josephine Baker and La Revue Negre From Ethnography To Performance PDFDocument28 pagesJosephine Baker and La Revue Negre From Ethnography To Performance PDFAna Cecilia CalleNo ratings yet

- Tourism MaketingrDocument136 pagesTourism MaketingrDegu SilvaNo ratings yet

- PAGCOR Site Regulatory ManualDocument4 pagesPAGCOR Site Regulatory Manualstaircasewit4No ratings yet

- Clifford James - Notes On Travel and TheoryDocument9 pagesClifford James - Notes On Travel and TheoryManuela Cayetana100% (1)

- Loire Valley (Eyewitness Travel Guides)Document266 pagesLoire Valley (Eyewitness Travel Guides)valentinz188% (8)

- Mrprintables Peg Dolls Winter WonderlandDocument4 pagesMrprintables Peg Dolls Winter WonderlandMirela Mogos Costache100% (1)

- Bourriaud - AltermodernDocument14 pagesBourriaud - Altermodernoceanontuesday100% (4)

- Images and Symbols: Studies in Religious SymbolismFrom EverandImages and Symbols: Studies in Religious SymbolismRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (22)

- Belting Contemporary ArtDocument24 pagesBelting Contemporary ArtMelissa PattersonNo ratings yet

- A Degree in a Book: Art History: Everything You Need to Know to Master the Subject - in One Book!From EverandA Degree in a Book: Art History: Everything You Need to Know to Master the Subject - in One Book!No ratings yet

- Culture/Archaeology:: The Dispersion of A Discipline and Its ObjectsDocument22 pagesCulture/Archaeology:: The Dispersion of A Discipline and Its ObjectscarolpecanhaNo ratings yet

- Issue 19 Death Writing in The Colonial MuseumsDocument52 pagesIssue 19 Death Writing in The Colonial Museumsapi-457693077No ratings yet

- Harris Clare - Future Ethnographic MuseumsDocument5 pagesHarris Clare - Future Ethnographic Museumshugo_hugoburgos6841No ratings yet

- Golden Mummies of Egypt: Interpreting identities from the Graeco-Roman periodFrom EverandGolden Mummies of Egypt: Interpreting identities from the Graeco-Roman periodNo ratings yet

- Douris and the Painters of Greek Vases: (Illustrated Edition)From EverandDouris and the Painters of Greek Vases: (Illustrated Edition)No ratings yet

- Kate Sturge Translation in The Ethnographic MuseumDocument9 pagesKate Sturge Translation in The Ethnographic MuseumKristjon06No ratings yet

- Xoticism Ethnic Exhibitions and The Power of The Gaze: BstractDocument16 pagesXoticism Ethnic Exhibitions and The Power of The Gaze: BstractJuan SotoNo ratings yet

- McCartan Blog PostDocument3 pagesMcCartan Blog PostoiseausauvageNo ratings yet

- Corbey 1993Document33 pagesCorbey 1993procrast3333No ratings yet

- Clifford - Notes On Travel and Theory (Complit - Utoronto.ca)Document7 pagesClifford - Notes On Travel and Theory (Complit - Utoronto.ca)Johir UddinNo ratings yet

- Frieze Magazine - Archive - The Other SideDocument5 pagesFrieze Magazine - Archive - The Other SideKenneth HeyneNo ratings yet

- Issues Archiving CulturesDocument24 pagesIssues Archiving CultureshphamNo ratings yet

- Bataille Architecture 1929Document3 pagesBataille Architecture 1929rdamico23No ratings yet

- 3607Document168 pages3607Vivian Braga SantosNo ratings yet

- Times of The CuratosDocument6 pagesTimes of The CuratosRevista Feminæ LiteraturaNo ratings yet

- Narrativizing Visual CultureDocument5 pagesNarrativizing Visual CultureAlexander CancioNo ratings yet

- CLIFFORDDocument3 pagesCLIFFORDMaria FretNo ratings yet

- Nochlin, Linda - The Imaginary OrientDocument27 pagesNochlin, Linda - The Imaginary OrientCatarina SantosNo ratings yet

- The Birth of Heritage: 'Le Moment Guizot'Document17 pagesThe Birth of Heritage: 'Le Moment Guizot'volodeaTisNo ratings yet

- Images of Exile and The Greeks of Grenoble: A Museum ExperienceDocument12 pagesImages of Exile and The Greeks of Grenoble: A Museum ExperienceSimion MehedintiNo ratings yet

- 28 1cleggDocument9 pages28 1cleggKATPONSNo ratings yet

- StefanArteni TheEastCentralEuropeanCulturalModel 2009 01Document90 pagesStefanArteni TheEastCentralEuropeanCulturalModel 2009 01stefan arteniNo ratings yet

- The Original SubalternDocument11 pagesThe Original SubalternBob MaestasNo ratings yet

- Clifford Notes On Travel and TheoryDocument7 pagesClifford Notes On Travel and TheoryAna MaríaNo ratings yet

- Wunderkammer ThesisDocument9 pagesWunderkammer Thesissandygrassolowell100% (1)

- PrimitivismDocument7 pagesPrimitivismnnnNo ratings yet

- Lee Weng Choy2002 - Biennale Time and Spectres of Exhibitn - Focas 4 (Jul 2002)Document14 pagesLee Weng Choy2002 - Biennale Time and Spectres of Exhibitn - Focas 4 (Jul 2002)issititNo ratings yet

- Module: History and Theory of Design 1 Module Code: BAHT6Y1 Unit of Learning: Unit 1 - The Elements of DesignDocument4 pagesModule: History and Theory of Design 1 Module Code: BAHT6Y1 Unit of Learning: Unit 1 - The Elements of DesignC-Jaye WarneyNo ratings yet

- How The West Was Won: Images in Transit, 2001Document11 pagesHow The West Was Won: Images in Transit, 2001Ruth RosengartenNo ratings yet

- Rosenthal - Visceral CultureDocument30 pagesRosenthal - Visceral CultureHattyjezzNo ratings yet

- A Dream FactoryDocument4 pagesA Dream FactoryalilbitteralilsweetNo ratings yet

- Jonathan Crary: Géricault, The Panorama, and Sites of Reality in Theearly Nineteenth CenturyDocument21 pagesJonathan Crary: Géricault, The Panorama, and Sites of Reality in Theearly Nineteenth Centuryadele_bbNo ratings yet

- 53-Article Text-176-1-10-20100119Document18 pages53-Article Text-176-1-10-20100119Inês FariaNo ratings yet

- 2021 Kitnick ArtforumDocument4 pages2021 Kitnick ArtforumLuNo ratings yet

- An Ideal Pact With A Pluriform Devil MMC 16 (2) 1997 192-197Document6 pagesAn Ideal Pact With A Pluriform Devil MMC 16 (2) 1997 192-197Riemer KnoopNo ratings yet

- The Whole Earth ShowDocument7 pagesThe Whole Earth Showarber0No ratings yet

- Mike Featherstone Archiving CulturesDocument24 pagesMike Featherstone Archiving CulturesEleftheria AkrivopoulouNo ratings yet

- Moreno Garcia Ibaes10Document24 pagesMoreno Garcia Ibaes10Leila SalemNo ratings yet

- 365 Moments To PhotographDocument7 pages365 Moments To PhotographTenaLekoNo ratings yet

- Americke Palacinke VeganDocument1 pageAmericke Palacinke VeganTenaLekoNo ratings yet

- Mamine Kiflice Sa SiromDocument1 pageMamine Kiflice Sa SiromTenaLekoNo ratings yet

- Magical in The Middle Ages Bib M 1Document2 pagesMagical in The Middle Ages Bib M 1TenaLekoNo ratings yet

- FeatherTheOwlDiffuser PIPwoBleeds USDocument2 pagesFeatherTheOwlDiffuser PIPwoBleeds USCyrus Ian A. LanuriasNo ratings yet

- Magical in The Middle Ages Bib M 1Document2 pagesMagical in The Middle Ages Bib M 1TenaLekoNo ratings yet

- Raspored Pds Knj-Ak - God. 14-15Document1 pageRaspored Pds Knj-Ak - God. 14-15TenaLekoNo ratings yet

- Animal Moves Animal Grooves An Animal Dance For Primary StudentsDocument5 pagesAnimal Moves Animal Grooves An Animal Dance For Primary StudentsBeth UnderrinerNo ratings yet

- C Documents and Settings Tena Local Settings Application Data Mozilla Firefox Profiles Nc0rpubhDocument7 pagesC Documents and Settings Tena Local Settings Application Data Mozilla Firefox Profiles Nc0rpubhTenaLekoNo ratings yet

- MS4082XRS Spec 141217Document2 pagesMS4082XRS Spec 141217TenaLekoNo ratings yet

- Magical in The Middle Ages Bib M 1Document2 pagesMagical in The Middle Ages Bib M 1TenaLekoNo ratings yet

- Qur'an - Bosanski PrevodDocument314 pagesQur'an - Bosanski Prevodkopa1982No ratings yet

- GreeceDocument15 pagesGreeceTenaLekoNo ratings yet

- Ferenc DeákDocument2 pagesFerenc DeákTenaLekoNo ratings yet

- Baltic Sea: ST IADocument1 pageBaltic Sea: ST IATenaLekoNo ratings yet

- Basic Physics: Topic 1 - Physical UnitsDocument1 pageBasic Physics: Topic 1 - Physical UnitsTenaLekoNo ratings yet

- Wbi Ps Uganda May 00 EngDocument38 pagesWbi Ps Uganda May 00 EngTenaLekoNo ratings yet

- African Systems of Kinship and MarriageDocument430 pagesAfrican Systems of Kinship and MarriageFelis_Demulcta_MitisNo ratings yet

- Staff TrainingDocument58 pagesStaff TrainingTRAVEL YARDNo ratings yet

- Synonym Antonym PDFDocument239 pagesSynonym Antonym PDFHilal Meral KaynakcıNo ratings yet

- QuestionareDocument37 pagesQuestionareEldho GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Budget HotelsDocument33 pagesBudget HotelsJay ArNo ratings yet

- Crabtales 035Document20 pagesCrabtales 035Crab TalesNo ratings yet

- Jim Corbett National ParkDocument11 pagesJim Corbett National ParkHardik PanchalNo ratings yet

- Terracotta Crafts Centre - ChittoorDocument20 pagesTerracotta Crafts Centre - ChittoorKiran KeswaniNo ratings yet

- SynchromarketingDocument1 pageSynchromarketingMattannhangNo ratings yet

- GROUP 3 RPH LOCAL HistoryDocument14 pagesGROUP 3 RPH LOCAL HistorySofia GarciaNo ratings yet

- MJL Brochure EnglishDocument15 pagesMJL Brochure Englishnunov_144376No ratings yet

- Bus TicketDocument2 pagesBus TicketNagabhushan BaddiNo ratings yet

- 06 Impacts of Tourism and HospitalityDocument20 pages06 Impacts of Tourism and HospitalityMary PaguioNo ratings yet

- Community Based TourismDocument12 pagesCommunity Based TourismKKNo ratings yet

- The Sibenik Times, July 4thDocument16 pagesThe Sibenik Times, July 4thSibenskilist100% (2)

- (MID-TERM 1) Đề thi giữa kỳ I trường THCS Lê Độ, Đà Nẵng, Việt NamDocument2 pages(MID-TERM 1) Đề thi giữa kỳ I trường THCS Lê Độ, Đà Nẵng, Việt NamShaki Chan100% (1)