Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Heal 201 Colonos

Uploaded by

Edith KuaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Heal 201 Colonos

Uploaded by

Edith KuaCopyright:

Available Formats

Do colonoscopies prevent colon cancer?

Two early studies from Canada found that colonoscopy protected patients from left-sided but not

proximal colon cancer [4] [5]. However, subsequent studies from the same centers found that

colonoscopy performed by gastroenterologists did provide right-sided protection [6] [7], as did

colonoscopy by doctors with higher cecal intubation rates and higher polypectomy rates [7]. Other

case-control studies from Germany and the United States also showed reductions in incidence [8] and

mortality [9] of right-sided cancer after colonoscopy.

Several studies presented at DDW 2013 extended observations on the protective effect of colonoscopy

against proximal versus distal colorectal cancer. In a case-control study performed in U.S.veterans 75

years of age and older, colonoscopy in the previous 10 years was associated with a 59% reduction in

the incidence of colorectal cancer and a 52% reduction in proximal colon cancer [10]. A case-control

study in an open-access colonoscopy Veterans Affairs system showed a 74% reduction in cancer

incidence associated with colonoscopy, including a 64% reduction in right-sided cancer [11]. A nested

case-control study in 4 geographically dispersed U.S.health plans identified an overall reduction in the

incidence of 72% after screening colonoscopy, including 61% for right-sided cancer [12]. Overall,

these results from recent case-control studies are consistent with the observation that colonoscopy

prevents right-sided colon cancer, although the risk reduction is less than that for left-sided cancer. In

a related study, analysis of interval cancers in the Intermountain Healthcare System in Utah found

that interval cancers tend to have a better prognosis than cancers discovered at the first colonoscopy,

with an odds ratio for an advanced stage cancer of 0.70 [13]. This is certainly good news.

Risk stratification to select patients for screening colonoscopy

As the pressure to reduce health expenditures increases, there is increasing pressure to use expensive

procedures like colonoscopy wisely and to reserve its use for the highest risk groups. Several studies

presented the results of risk stratification schemes to predict high-yield screening colonoscopy.

Examining screening colonoscopies in the Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative Data Base, Lieberman

et al [14] used the prevalence of advanced lesions in white men 50 to 54 years of age as their

baseline level of risk for initiation of screening. There were 146,347 blacks and whites undergoing

screening colonoscopy at younger than 60 years of age. The risk of advanced lesions was similar in

white and black men age younger than 50 years of age but increased (odds ratio 1.17) for black men

50 to 59 years of age compared with white men. The risk of advanced lesions in black women was

considerably higher than that in white women, both at younger than 50 years of age and in the 50- to

59-year age group.The results were interpreted to suggest that screening should start in blacks and

whites at the same age, but indicating the need to intensify screening efforts among blacks beginning

at age 50 years of age. Imperiale et al [15] derived a risk index based on coefficients for age, sex,

waist circumference, cigarette smoking, and family history of colorectal cancer in 1 or more first-

degree relatives. Risk scores ranged from 0 to 12 and were grouped into 4 categories. The risk of

advanced neoplasia in the very low risk score group was 1.9%, 4.7% for the low-risk score group,

9.9% for the intermediate-risk score group, and 25% for the high-risk score group.The predictors

held up well in a validation set. There were 5 colorectal cancers in total in the very low and low-risk

groups had, all of which were distal. The authors proposed sending very low and low-risk groups to

sigmoidoscopy and the intermediate- and high-risk groups to colonoscopy.

These results suggest that self-referral by surgical endoscopists is a problem in clinical practice, a

problem anecdotally often identified by gastroenterologists. There should be mechanisms in place for

gastroenterologists or specialists in complex polypectomy to review photographs of lesions identified

by surgeons and other endoscopists to determine their endoscopic resectability before patients are

taken to surgery(26)

Variation between endoscopists in quality performance during colonoscopy has now been

demonstrated for adenoma detection, cancer prevention, completeness of polyp resection, and

appropriate use of screening and surveillance intervals. Mahadev et al [43] studied rates of suboptimal

bowel preparation labeled as fair, poor, or unsatisfactory among 11 separate gastroenterologists who

had performed more than 50 screening colonoscopies during a 1-year study. The rate of suboptimal

preparation varied widely from 3% to 40% and did not correlate with adenoma detection. Certainly

some of these differences could be related to interpretation of bowel preparation quality, as opposed

to the actual level of preparation, but they indicate another area of variable performance that can

affect colonoscopy outcomes and cost-effectiveness

Colonoscopy quality has improved during the past decade due to advances in image

technology, bowel preparation and sedation techniques. Nonetheless, opportunities for

further improvement in outcome measures of colonoscopy remain. For example, studies

from diverse settings have shown that colonoscopy is less effective in preventing proximal

compared with distal cancers. Improved detection of proximal adenomas and serrated

lesions would likely help to bridge this difference in outcome between proximal and distal

cancers.

Quality is a cornerstone of the new healthcare landscape. As endoscopists, we will be held

accountable not merely for completing our procedures but also for their quality and

appropriateness. Evidence-based quality measures, designed to assess the outcomes of our

procedures, are being developed and will be judged accordingly. The ADR, a validated measure

of quality that correlates closely with the risk of an interval carcinoma after colonoscopy, will

probably remain the most important outcome measure of screening colonoscopy.

Other quality measures, such as the number of adenomas per patient and number of sessile

serrated lesions per patient, are being assessed as well. Methods to improve lesion detection,

including better quality bowel preparation, cap-assisted colonoscopy, water-assisted colonoscopy

and image-enhanced techniques such as chromoendoscopy and autofluorescence imaging are all

under active investigation.

The 'quality imperative' is also focused on the efficient utilization of resources. Better

understanding of an individual's colorectal cancer risk, based upon their family and personal

history will permit better stratification of patients into different surveillance intervals. We are

likely to see better guidance in the management of patients with one or more sessile serrated

lesions within the proximal colon.

Finally, the primacy of colonoscopy as the gold standard for colorectal cancer screening will be

challenged during the next 5 years. Fecal immunochemical testing and stool DNA both

pose real threats to colonoscopy, based upon their simplicity and cost. As endoscopists,

we must heed the quality initiative and ensure that each of us provide high quality examinations

to the right patients at the right times.

Inadequate bowel preparation

An adequate bowel preparation is defined as one that permits the detection of all

polyps >5 mm in size. While providing a conceptual framework for understanding an

acceptable preparation, this definition has limited utility in clinical practice. From an operational

standpoint, a more useful definition of an adequate preparation is one that exposes 90% or more

of the mucosal surface. Most bowel preparation rating scales further stratify the term 'adequate'

into good or excellent, and 'inadequate' into fair or poor. The preparation scales differ somewhat

in their definitions of each level.

Roughly one in four colonoscopies has an inadequate preparation. Prolonged examination

times as well as reduced rates of cecal intubation and adenoma detection have been documented

in procedures where the bowel preparation is considered to be incomplete. Furthermore, patients

with inadequate cleansing are often brought back for repeat examination sooner than would

otherwise be recommended. Consequently, inadequate bowel preparation limits the efficacy of

colonoscopy and leads to additional costs, risk of complications and, in some instances, a lower

compliance rate with screening/surveillance guidelines due to frustration and disappointment

with the process.

The impact of an inadequate bowel preparation on missed lesions was recently analyzed by

investigators in New York (NY, USA) and St Louis (MO, USA), who retrospectively analyzed the

findings of a second colonoscopy performed in selected patients with an inadequate bowel

preparation 1-3 years after the index examination

[17,18]

. The per-patient rates of missed

adenomas were 25 (NY) and 33% (MO). Even more impressive were the per-adenoma

miss rates of 42 and 48%, respectively. In view of these high rates of missed lesions,

it would seem that the most prudent advice for patients with poor preparation and

limited visibility on examination is to interrupt the procedure and to repeat the

examination within 24 h following additional efforts at bowel cleansing.

Predictors of inadequate preparation

Older age, constipation, higher BMI and significant comorbid disease have consistently

been shown to be independent predictors of patients who are more likely to have an

inadequate bowel preparation

[19]

. An Italian multicenter study prospectively evaluated 2811

consecutive subjects undergoing colonoscopy

[20]

. Bowel preparation quality was rated as

excellent, good, fair or poor. Based upon their multivariate analysis, they developed a clinically-

based model having both a sensitivity and specificity of roughly 60%. In other words, the model

identified nearly two of every three patients with an inadequate bowel preparation, while

misclassifying 40% of patients. As expected, male gender, older age and higher BMI were

independent predictors, as were advanced diabetes, liver disease, previous colorectal surgery

and Parkinson's disease. While efforts to develop a clinical predictor of inadequate bowel

cleansing are worthwhile, the proposed model is unlikely to receive widespread interest until its

predictive score approaches 80-90%.

Along similar lines, a retrospective study by Ben-Horin et al . serves to remind us that patients

with a failed bowel preparation need a more intensive regimen the second time around

[21]

. In

their series of 6990 colonoscopies, 372 procedures (5.3%) were considered failures due to an

inadequate bowel preparation and a repeat examination was advised. Of those subjects

undergoing a second examination, nearly one in four (23%) had a failed preparation the second

time around. Patients having their repeated procedure the day after their failed examination

were more likely to have adequate cleansing on repeat colonoscopy compared with those having

their repeat examination at a later time. Providers should recognize those patient-related factors

that increase the likelihood of a suboptimal bowel preparation and modify the bowel cleansing

regimen in those patients accordingly.

The propofol controversy

Sedation for endoscopy has traditionally been performed by an endoscopist along with a specially

trained nurse. The preferred sedation agents included a benzodiazepine combined with an opioid

analgesic. The introduction of propofol by anesthesiologists for brief endoscopic procedures has

forever altered how endoscopists and patients view endoscopic sedation. During the past 15

years, propofol has become the drug of choice among many endoscopists due to its favorable

pharmaceutical properties and outstanding safety profile. Controversy continues to exist,

however, regarding the administration of propofol by a trained nurse working under the

supervision of an endoscopist. In spite of an evidence-based consensus statement issued jointly

by ASGE, American College of Gastroenterology, the American Gastroenterological Association

and American Association for the Study of Liver Disease supporting the practice, the ASA

continues to maintain that propofol should be administered only by anesthesia providers

[29]

.

This debate was fueled by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services interpretative

guidelines on deep sedation issued in 2009-2010, which seemed to support the position that

propofol administration should be limited to anesthesia specialists

[101]

. The practical and

economic implications of their directive have been described by Rex

[30]

. He points out that

the routine use of an anesthesia provider to oversee sedation during endoscopy could

add as much as US $5 billion annually to the USA healthcare budget. Several alternatives,

including endoscopist-directed propofol, computer-assisted propofol delivery and new sedation

agents with product labels that permit their use by nonanesthesiologists may one day provide

acceptable, lower-cost options for procedural sedation.

This article summarizes recent developments in colonoscopy with particular emphasis on

three areas: bowel preparation, premedication and endoscopic sedation. Three important

concepts warrant special consideration. First, split-dose bowel preparation remains a key

concept for enhancing the quality of colonoscopy, especially the proximal colon. This

observation comes at a time when the value of colonoscopy within the proximal colon is

being debated. Some authors have even opined that the timing of preparation

administration is more important than the formula itself. Endoscopists around the world

should embrace the principle of split-dose preparation. Second, endoscopists are

encouraged to become familiar with the new antithrombin and antiplatelet drugs that are

being used increasingly by patients who present for elective endoscopy. Based upon the

specific procedure being performed, a decision analysis is required to decide whether to

maintain the agents during the periprocedural period and accept a risk of bleeding or to

discontinue such drugs prior to the examination and expose the patient to an increased risk

of thrombosis and its sequelae. Third, endoscopists everywhere continue to struggle over

what is appropriate sedation for endoscopy. Has propofol become the standard of care,

as some endoscopists believe, or is its use 'discretionary' as others have

indicated

[44]

? These and other related issues make endoscopic sedation possibly the most

contentious topic within the field of gastroenterology today.

Colonoscopy - complications - perforation - hemorrhage - postpolypectomy syndrome

References

Lewis, J. R., & Cohen, L. B. (2013). Update on colonoscopy preparation, premedication and

sedation. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 7(1), 77+. Retrieved from

http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA312892152&v=2

.1&u=ubcolumbia&it=r&p=HRCA&sw=w&asid=3705bcfb62e42b4b9a9ffca5ee95a8e5

Rex, D (2013) Colonoscopy. Endoscopy, 45,9, 756-761

DOI: 10.1055/s-0033-1344630

You might also like

- Module 2 Vocabulary Lists Clinical and Grammatical SuffixesDocument4 pagesModule 2 Vocabulary Lists Clinical and Grammatical SuffixesEdith KuaNo ratings yet

- EOSC 310 Questions (UBC 2016)Document5 pagesEOSC 310 Questions (UBC 2016)Edith KuaNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 4 QuestionDocument4 pagesTutorial 4 QuestionEdith KuaNo ratings yet

- Dr. Etazaz Econometrics Notes PDFDocument98 pagesDr. Etazaz Econometrics Notes PDFMuhammadYunasKhan100% (1)

- Watson Introduccion A La Econometria PDFDocument253 pagesWatson Introduccion A La Econometria PDF131270No ratings yet

- Econ 427 Assignment 4 Instrumental Variables ModelsDocument4 pagesEcon 427 Assignment 4 Instrumental Variables ModelsEdith KuaNo ratings yet

- Econometrics Question and AnswerDocument7 pagesEconometrics Question and AnswerEdith KuaNo ratings yet

- 2015 Midterm SolutionsDocument7 pages2015 Midterm SolutionsEdith Kua100% (1)

- 03.econ427 2016 SW6Document41 pages03.econ427 2016 SW6Edith KuaNo ratings yet

- 06.Econ427C 2016 SW10Document73 pages06.Econ427C 2016 SW10Edith KuaNo ratings yet

- Econ 491: Econometrics Stock and WatsonDocument63 pagesEcon 491: Econometrics Stock and WatsonEdith KuaNo ratings yet

- 06.Econ427C 2016 SW10Document73 pages06.Econ427C 2016 SW10Edith KuaNo ratings yet

- IV - Exchange Rate DeterminationDocument40 pagesIV - Exchange Rate DeterminationEdith KuaNo ratings yet

- Intermediate Macroeconomics 205Document9 pagesIntermediate Macroeconomics 205Edith KuaNo ratings yet

- ECON 345 Money and Banking Chapter 2 Functions Markets IntermediariesDocument20 pagesECON 345 Money and Banking Chapter 2 Functions Markets IntermediariesEdith KuaNo ratings yet

- 5a. Organizational Lab HPW KEYDocument8 pages5a. Organizational Lab HPW KEYEdith Kua100% (2)

- ECON 345 Money and Banking Chapter 1 OverviewDocument27 pagesECON 345 Money and Banking Chapter 1 OverviewEdith KuaNo ratings yet

- IV - Exchange Rate DeterminationDocument40 pagesIV - Exchange Rate DeterminationEdith KuaNo ratings yet

- Why The West? (Ferguson)Document13 pagesWhy The West? (Ferguson)Andrew SernatingerNo ratings yet

- MacroeconomicsDocument4 pagesMacroeconomicsEdith KuaNo ratings yet

- How central bank actions impact pricesDocument5 pagesHow central bank actions impact pricesTatiana Rotaru0% (1)

- Instructor'S Manual: International TradeDocument206 pagesInstructor'S Manual: International Tradebigeaz50% (4)

- Economic History: Global Interactions (1450 - 1750)Document26 pagesEconomic History: Global Interactions (1450 - 1750)Edith KuaNo ratings yet

- Equation List For Lecture 1 - 4 (Till Jan 17)Document1 pageEquation List For Lecture 1 - 4 (Till Jan 17)Edith KuaNo ratings yet

- Lazear Gibbs 2007Document157 pagesLazear Gibbs 2007Edith KuaNo ratings yet

- New Era, New Responsibilities: 174 Vital Speeches of The DayDocument6 pagesNew Era, New Responsibilities: 174 Vital Speeches of The DayEdith KuaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- International Ayurvedic Medical Journal: Case Report ISSN: 2320 5091 Impact Factor: 4.018Document4 pagesInternational Ayurvedic Medical Journal: Case Report ISSN: 2320 5091 Impact Factor: 4.018triplete123No ratings yet

- Relaxant Effect of Thymus VulgarisDocument4 pagesRelaxant Effect of Thymus VulgarisgangaNo ratings yet

- Juan Bertran Figueras, History of Homeopathy in Spain (Catalonia)Document12 pagesJuan Bertran Figueras, History of Homeopathy in Spain (Catalonia)Maria-Neus Lorenzo-Galés100% (2)

- Communicable Disease Surveillance in Animal PopulationDocument15 pagesCommunicable Disease Surveillance in Animal Populationsamwel danielNo ratings yet

- Impact of Philippines' 4Ps cash transfer programme on healthcare and educationDocument3 pagesImpact of Philippines' 4Ps cash transfer programme on healthcare and educationJustine Martin PrejillanaNo ratings yet

- Acrylic Partial Dentures More Satisfying Than Cast DenturesDocument4 pagesAcrylic Partial Dentures More Satisfying Than Cast DenturesAkikoz N SevenNo ratings yet

- STELLA Edited 4-1Document41 pagesSTELLA Edited 4-1Okwany JimmyNo ratings yet

- Post Mortem CareDocument2 pagesPost Mortem Carebea pegadNo ratings yet

- Safeguarding Policy Analysis of An NHS TrustDocument14 pagesSafeguarding Policy Analysis of An NHS Trustrose muabeNo ratings yet

- Ethical Issues in Nursing Research:: Deontological PerspectiveDocument11 pagesEthical Issues in Nursing Research:: Deontological PerspectiveJM JavienNo ratings yet

- Neuropsychopharmacology The Fifth Generation of Progress: 5th EditionDocument2,054 pagesNeuropsychopharmacology The Fifth Generation of Progress: 5th EditiondanilomarandolaNo ratings yet

- License Application (LIC1558941)Document2 pagesLicense Application (LIC1558941)souq alkanzNo ratings yet

- CSC Job Portal: Mgo San Leonardo, Nueva Ecija - Region IiiDocument1 pageCSC Job Portal: Mgo San Leonardo, Nueva Ecija - Region Iiirandiey john abelleraNo ratings yet

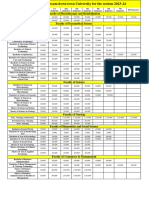

- Fees Structure Assam Down Town University For The Session 2023 2Document2 pagesFees Structure Assam Down Town University For The Session 2023 2Debashish SharmaNo ratings yet

- Maklumat Vaksinasi: Vaccination DetailsDocument2 pagesMaklumat Vaksinasi: Vaccination Detailsibrahim mohd rubaiNo ratings yet

- Amended Patient Classification Policy ManualDocument25 pagesAmended Patient Classification Policy ManualLaura Lopez GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Client Satisfaction and Quality of Health Care in Rural BangladeshDocument6 pagesClient Satisfaction and Quality of Health Care in Rural BangladeshMizanur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Chealthnet - OUR TEAMDocument2 pagesChealthnet - OUR TEAMshaikhbwcNo ratings yet

- Simple Triage and Rapid TreatmentDocument9 pagesSimple Triage and Rapid TreatmentGung IndrayanaNo ratings yet

- Legal Aspects of Perioperative NursingDocument9 pagesLegal Aspects of Perioperative NursingZerrie lei Hart100% (2)

- Memo No. 2022-59 - Submission of Updated PHIC and PRC License of Medical SpecialistsDocument8 pagesMemo No. 2022-59 - Submission of Updated PHIC and PRC License of Medical SpecialistsPaul Rizel LedesmaNo ratings yet

- Annual Report FY 2017-2018: Mobile Eye ClinicDocument18 pagesAnnual Report FY 2017-2018: Mobile Eye ClinicUMEC Young Professionals InitiativeNo ratings yet

- Suvarnaprashana Therapy in Children ConcDocument3 pagesSuvarnaprashana Therapy in Children ConcBhavana GangurdeNo ratings yet

- UK M P 004 v6.0 User-ManualDocument21 pagesUK M P 004 v6.0 User-ManualdrumerNo ratings yet

- Public Health Nurse PHN Final Exam Past Questions For WAHEBDocument3 pagesPublic Health Nurse PHN Final Exam Past Questions For WAHEBCharles Obaleagbon86% (7)

- Final Coaching Part and B - StudentDocument15 pagesFinal Coaching Part and B - StudentAshley Ann Flores100% (1)

- Speech Adult Case History - NLDocument4 pagesSpeech Adult Case History - NLHarshit AmbeshNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Career Guide - Definition, Objectives & AreasDocument6 pagesNutrition Career Guide - Definition, Objectives & Areastomas rNo ratings yet

- EBP Manual: A Guide to Evidence-Based PracticeDocument53 pagesEBP Manual: A Guide to Evidence-Based PracticesyamafiyahNo ratings yet

- Brgy. Talandang and Baganihan 2022 ConsolidatedDocument6 pagesBrgy. Talandang and Baganihan 2022 Consolidatedevelyn d. pepitoNo ratings yet