Professional Documents

Culture Documents

OleBjerg PDF

Uploaded by

Luiz Felipe MonteiroOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

OleBjerg PDF

Uploaded by

Luiz Felipe MonteiroCopyright:

Available Formats

280 NORDIC STUDIES ON ALCOHOL AND DRUGS VOL. 27.

2010

.

3

Where there is

capitalism, there shall

be addiction

Ole Bjerg

For tt p kapitalismen. Ludomani, narkomani

og kbemani. [Too close to capitalism. Ludomania,

narcomania and shopoholism].

Kbenhavns Universitet: Museum Tusculanums

Forlag, 2009. 168 pages.

T

he book For tt p kapitalismen. Lu- Lu-

domani, narkomani, kbemani [Too

close to capitalism. Ludomania, narcoma-

nia, shopoholism] by Danish sociologist Ole

Bjerg found a place in my bag for the whole

of spring 2010. My initial intention was to

read it and quickly write a brief announce-

ment. However, the book turned out to de-

mand and deserve more space and attention.

Overall, I must say it is a nicely written phil-

osophical piece, complementing texts by

scholars such as Gerda Reith, Eve Sedwick

Kosowsky and Bruce Alexander. While los-

ing some of its sting toward the end, Bjergs

style is mature and elegant with a straight-

forward and focused grip.

Bjerg takes his point of departure rst and

foremost in the Lacanian trinity of the Real,

the Symbolic and the Imaginary. His core

discussion concerns the ways in which real-

life addiction problems are dependent on

peoples perceptions and how the imagery is

fed by the capitalist order. The relevance of

the imaginary and the symbolic in this equa-

tion may not sound revolutionary and new to

Nordic addiction scholars, who may have en-

countered such research initiatives as those

of the IMAGES consortium

1

. It is now widely

recognised that how we perceive, fantasise

and build expectations around certain action

will have implications on what we actually

decide to do, how we understand our action

and how we see the possibilities of changing

our behavioural patterns. Bjerg demonstrates

how certain mechanisms in the capitalist

system rely on peoples distance to reality.

In order for capitalism to work, we need to

desire objects, people and lifestyles. We will

do so as long as the illusion about their in-

herent values, benets and attractiveness is

kept alive. The addict has consumed away

this illusion and has consequently come too

close to the truth.

A crucial aspect of the modern conception

of addiction lies in the discrepancy between

wanting to and having to ingest substances,

or perform certain action. Bjerg describes the

shift between the two states by comparing it

to a Marxist circulation of objects. For ad-

dictions to emerge in the rst place people

should manage their desires with capitalist

circulations of objects: money, bodies and

goods. We are programmed to desire certain

things in life, but when we come too close to

the truth of these objects we slide into cir-

culations of another nature, of a pathologi-

cal kind, or mania. This displaced circula-

tion of objects does something to humans

and constitutes a (capitalist) precondition

for addictions. The process of sliding into

the displaced order can be exemplied by a

gambler who feels that he is able to affect or

predict the outcome of the game or that he is

chosen by destiny to get the big win. This is

crucial for his desire to game, even though

his beliefs can easily be contradicted by the

mathematical (un)likelihood of winning, or

just by any common reasoning. Nevertheless,

the gambler must buy into this illusion when

he initiates the gaming, and after a while

he may be propelled into the displaced ad-

dicted order, in which his hierarchy of needs

and priorities have become different:

It has been said that the bumble bee

should, physiologically speaking, not be

able to y. However, the bee is unaware

of this fact and will therefore y around

and be happy in its unawareness of this

fact. The capitalist subject is, in the same

manner, an impossible structure. When

Book

review

281 NORDIC STUDIES ON ALCOHOL AND DRUGS V O L . 27. 2010

.

3

capitalism functions well it is because

we are not aware of its impossibility. The

compulsive gambler is like the bumble bee

that has suddenly admitted a truth regard-

ing capitalism, which makes it impossible

for him to function in the capitalistic so-

ciety. He has come too close to the money

(Bjerg 2008, 39, translated by M.H.)

Bjerg allies with theorists who analyse the

psychological through the social and vice

versa. His reasoning on the birth of addic-

tive behaviour is informed, for example, by

ieks notion on the self as incomplete, re-

flecting itself in its social context and look-

ing for completion. The self is an empty

category to be filled by linguistic and social

processes. This is of course very close to Gid-

dens discussion on the birth of addictions

in modernity stemming from the myriad of

choices that the individual has to make in

her daily life while answering the question

of How shall I live? The illusion of the cap-

italist ideology is the satisfaction of desire,

the filling of the gap in the being of the self.

Again, a precondition is that the subjects

needs and desires are bred on the level of

fantasy and are never to be actually realised.

Addiction is the state when we have come

too close to the objects, when the capitalist

fantasy no longer is appealing, and when the

self will channel its needs into other circula-

tions. The self has come to be too close to

capitalism, and the shortage seeks expres-

sion in an individual state of mania.

In narcomania, our relationship to the body

crucially determines the sliding over to an ad-

dicted order. The comprehension of the self

as a craving being is to a large extent equiva-

lent to the comprehension of the body as de-

manding, desiring and enjoying. The drug ad-

dict is steered by the desire of drug-induced

pleasure and is reduced to a mere organism.

The reduction to an organism can be viewed

as an elimination of the self through an ex-

treme one-way process in a desire-economy:

For the compulsive gambler money is

only paper, and its function is reduced to

the admittance to more gambling. For the

drug addict the body is reduced to body

tissue, blood and nerve bres, and its

function is reduced to generating pleas-

ure or pain (ibid. 107)

The problem with the drug addict is that he

knows too much. He knows that the body is

a chemically manipulated entity and that

the drugs can give him absolute pleasure

the bliss which he is in the capitalist soci-

ety continuously encouraged to desire and

chase. He knows that he can only get a dilut-

ed version of this state on the other (non-ad-

dicted) side, explains Bjerg. This too close

an insight into the body as an apparatus of

chemical (brain) processes is displaced from

the symbolic order, which is so crucial for

upholding the capitalism system (creating

needs and desires for commodities and for

states of being). I would prefer to call it a

consumerism order, but I can clearly see a

parallel to many other phenomena, such as

the symbolic order of love. An important as-

sumption when we plan and build our lives

is the premise that romantic emotions are

something other than chemical processes in

the brain. This is actually a crucial assump-

tion in the symbolic and the imaginary of

consumer society, perhaps one of the most

crucial.

When it comes to shopaholism as a pathol-

ogy, Bjerg gets closer to theories of moder-

nity and their view on the self as in a con-

stant self-reexivity process of dening and

construing itself. What I like very much is

that Bjerg takes in Baudrillardian thought on

the function of consumption as generating

values on other levels. And it is also in this

chapter that I experience Bjerg as a writer

with a sense for the contemporary. Although

he is leaning his theorisation on Marxist

thought, he is well aware of todays society

working in another manner than that which

once engaged our parents generation (on

the back cover I notice that Bjerg is born in

the same year as myself). Changes in society

can today result from forces in the symbolic,

which follow other logics than the classic

282 NORDIC STUDIES ON ALCOHOL AND DRUGS VOL. 27. 2010

.

3

ones of the exploiters and the oppressors.

I would not call it the death of ideology,

as it is very much supported by a hedonistic

and narcissistic capitalist and consumerist

ideology. And I do agree with Bjerg that a

capitalist society upholds and supports ad-

diction problems in its logics of functioning.

But I am nevertheless glad that Bjerg does

not point out specic political projects, as

this could perhaps have banalised the objec-

tives of the book.

On the notion of consumerism as breed-

ing shopaholism which must sound self-

evident for the reader I want to recommend

Anne Cronins sharp treatise (2004) on com-

modities and compulsions, which describes

cleptomania as a result of the creation of de-

partment stores in the nineteenth century. A

chapter in a book on advertising myths, this

piece may have passed unnoticed by schol-

ars in the addiction eld.

I imagine Bjergs working process as stem-

ming from a certain moment of insight or

clarity as regards an understanding of the

phenomenon of addiction in the light of

Marxist, Lacanian and iekian thought. He

is clearly fuelled by this intellectual adren-

alin kick. In my own opinion, his track is

one of the most interesting and important

in theorising addiction today: What, and

why is addiction in contemporary society?

What function do these mania states have

for us? No doubt, circulations of goods and

the fullment of desires play a crucial role in

the puzzle. Although not a completely new

thought, the literature on the connection be-

tween the free-market society and addiction

seems to be growing very slowly, but there

are some interesting pieces around, such as

Reith 2004, Cronin 2004, Alexander 2004,

Alexander 2008. Writes Reith (2004, 283):

the notion of addiction has particular

valence in advanced liberal societies,

where an unprecedented emphasis on

the values of freedom, autonomy and

choice not only encourage the condi-

tions for its proliferation into ever wider

areas of social life, but also reveal deep

tensions within the ideology of consum-

erism itself.

In view of this I find Bjergs book of special

relevance also for apprehending society at

large.

When it comes to the structure of the book,

I nd the philosophical introduction un-

necessarily long, and the last chapter could

have expressed an even louder crescendo.

In his reasoning around the reality escape

of the gambler Bjerg could have elaborated

on the spatial and the temporal dimensions

of addiction. It is here that we nd exciting

relations not only between the real and the

imaginary and the symbolic, but also a con-

nection to understandings of the problems

which rises from contemporary societal

trends such as globalisation or digitalisa-

tion. Moreover, the Baudrillardian track

could here have taken an extra dimension.

But then again, I may be projecting my own

interests and work onto the book.

The spontaneous message that I would

like to mediate after reading this book is that

addiction scholars can go on forever and

ever producing short research publications,

offering glimpses into the phenomenon of

addiction on a wide disciplinary scale from

brain scans to cultural analysis of the theme

in high culture. However, somebody has

to do the sometimes lonely and demand-

ing intellectual dirty work of theorising a

framework for the developments we are wit-

nessing. Each initiative in this direction is to

be saluted and cherished: Bjergs book is a

warmly welcomed addition in our eld.

Matilda Hellman, project coordinator

Nordic Centre for Welfare and Social Issues (NVC)

Annegatan 29 A 23

00100 Helsingfors, Finland

E-mail: matilda.hellman@nordicwelfare.org

NOTES

1) Theories of Addiction and Images of Ad- Theories of Addiction and Images of Ad-

dictive Behaviours (IMAGES). See: http://

blogs.helsinki./imagesofaddiction/

283 NORDIC STUDIES ON ALCOHOL AND DRUGS V O L . 27. 2010

.

3

REFERENCES

Alexander, B. (2004): A historical analysis of

addiction. In: Rosenqvist, P. & Blomqvist,

J. & Koski-Jnnes, A. & jesj, L. (2004):

Addiction and life course. NAD publication

44. Helsinki: Hakapaino

Alexander, B. (2008): The Globalisation of Ad-

diction. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Cronin, A.M. (2004): Images, commodities and

compulsions: consumption controversies

of the nineteenth century. In: Cronin, A.M.

(2004): Advertising myths. The strange

half-lives of images and commodities.

London and New York: Routledge Taylor &

Francis Group

Reith, G. (2004): Consumption and its discon-

tents: addictions, identity and the problems

of freedom. The British Journal of Sociology

55 (2): 283300.

You might also like

- Lacan On The Discourse of Capitalism Critical Prospects: Philosophy, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan UniversityDocument18 pagesLacan On The Discourse of Capitalism Critical Prospects: Philosophy, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan UniversityLuiz Felipe MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Éric Laurent: Guiding Principles For Any Psychoanalytic ActDocument3 pagesÉric Laurent: Guiding Principles For Any Psychoanalytic ActLuiz Felipe MonteiroNo ratings yet

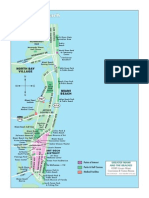

- M Miia Am Mii B Be Ea Ac CH H: Greater Miami and The BeachesDocument1 pageM Miia Am Mii B Be Ea Ac CH H: Greater Miami and The BeachesLuiz Felipe MonteiroNo ratings yet

- JAMillerSx PDFDocument6 pagesJAMillerSx PDFLuiz Felipe MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Goza 1Document288 pagesGoza 1Karla Rampim XavierNo ratings yet

- Lac Ani An Compass 7Document13 pagesLac Ani An Compass 7ninanana987551No ratings yet

- "I Shall Be With You On Your Wedding-Night" Lacan and The Uncanny PDFDocument20 pages"I Shall Be With You On Your Wedding-Night" Lacan and The Uncanny PDFfaphoneNo ratings yet

- Elibrary by Subject 110706Document1 pageElibrary by Subject 110706JasperMelNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Approachesto DACounselingDocument143 pagesApproachesto DACounselingViviana Larisa HodeaNo ratings yet

- Fearless by Steve Chandler PDFDocument161 pagesFearless by Steve Chandler PDFanka100% (1)

- Homeless To HarvardDocument1 pageHomeless To HarvardDianna Lynn MolinaNo ratings yet

- The Problem of Drug Abuse in PunjabDocument20 pagesThe Problem of Drug Abuse in PunjabAnmol AnmolNo ratings yet

- Social Networking Addiction ScaleDocument17 pagesSocial Networking Addiction ScaleEuNo ratings yet

- Drug Rehabitation Center SynopsisDocument6 pagesDrug Rehabitation Center SynopsisPriya Dharshini Pd100% (1)

- Physicians Desk Reference (PDR) For Pain ManagementDocument285 pagesPhysicians Desk Reference (PDR) For Pain ManagementDante36100% (2)

- Facing Codependence - Book ReviewDocument1 pageFacing Codependence - Book ReviewSPPrivate_0% (1)

- Teenagers at Risk of Internet AddictionDocument2 pagesTeenagers at Risk of Internet AddictionJoe JaprinNo ratings yet

- Hamdard Community Center Case SolutionDocument4 pagesHamdard Community Center Case SolutionShahzaib MaharNo ratings yet

- 1 - Sir Raqui 3rd Quarter CADAC Meeting 09272018Document28 pages1 - Sir Raqui 3rd Quarter CADAC Meeting 09272018Barangay Talon UnoNo ratings yet

- Chapter IxDocument5 pagesChapter IxGonzalo JáureguiNo ratings yet

- 110 ch3Document3 pages110 ch3Hitesh KhuranaNo ratings yet

- Acute Alcohol IntoxicationDocument7 pagesAcute Alcohol IntoxicationEnrique Téllez CentenoNo ratings yet

- Spada Marcantonio, An Overview of Problematic Internet Use, Add Behav 2014Document6 pagesSpada Marcantonio, An Overview of Problematic Internet Use, Add Behav 2014Emmanuel Manolis KosadinosNo ratings yet

- Za Cda Cannabis Position 2009 PDFDocument73 pagesZa Cda Cannabis Position 2009 PDFbillymamboNo ratings yet

- Seminar On Alcohol Related Disorder and Its ManagementDocument41 pagesSeminar On Alcohol Related Disorder and Its ManagementSoumyasree.pNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan in MAPEH 9 (Health) : Antonio R. Lapiz National High School Jaguimit, City of Naga, CebuDocument4 pagesLesson Plan in MAPEH 9 (Health) : Antonio R. Lapiz National High School Jaguimit, City of Naga, CebuJeraldine RepolloNo ratings yet

- AP Psychology Module 7-10Document6 pagesAP Psychology Module 7-10Izzy ButzirusNo ratings yet

- Picking A Topic For Writing Your Research Papers On AlcoholismDocument4 pagesPicking A Topic For Writing Your Research Papers On AlcoholismJohn Kenneth FetizananNo ratings yet

- Soal B.ing To 3BDocument12 pagesSoal B.ing To 3BLaras AyuningtyasNo ratings yet

- Intro To Neuroscience Class NotesDocument50 pagesIntro To Neuroscience Class NotesNickNalboneNo ratings yet

- Cocaine Addiction Severity TestDocument4 pagesCocaine Addiction Severity TestDharline Abbygale Garvida AgullanaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To CNS PharmacologyDocument9 pagesIntroduction To CNS PharmacologyAbraham Daniel Campo Cruz100% (1)

- What Are Electronic Cigarettes or Vapes?Document2 pagesWhat Are Electronic Cigarettes or Vapes?Sevalingam DevarajanNo ratings yet

- Housing First - Karis Inc.Document19 pagesHousing First - Karis Inc.gjredpillNo ratings yet

- Illicit Use of Drugs Among The Youth and Adults in The Frances Baard Region Northern Cape, South AfricaDocument10 pagesIllicit Use of Drugs Among The Youth and Adults in The Frances Baard Region Northern Cape, South AfricaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Chapter # 1: 1.1statement of The ProblemDocument12 pagesChapter # 1: 1.1statement of The ProblemShams Ud Din SahitoNo ratings yet

- Gourmand Syndrome 1997Document6 pagesGourmand Syndrome 1997Timothy MiddletonNo ratings yet

- Sta 108 PDFDocument5 pagesSta 108 PDFafdolllNo ratings yet