Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Discourse in Use Bloome

Uploaded by

najakat0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

35 views29 pagesdcdcd

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentdcdcd

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

35 views29 pagesDiscourse in Use Bloome

Uploaded by

najakatdcdcd

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 29

DISCOURSE-IN-USE

David Bloome and Caroline Clark

The Ohio State University

Manuscript prepared for Complementary Methods for Research in Education co-edited by Judith

reen! re" Camilli! and #atricia $lmore to be published by the %merican $ducational &esearch

%ssociation' %ddress for correspondence( David Bloome! )an"ua"e! )iteracy * Culture! School

of Teachin" * )earnin"! The Ohio State University! +,-B &amseyer .all! +/' 0' 0oodruff

%venue! Columbus! Ohio 12+,3 bloome',4osu'edu

Discourse-5n-Use

The concept of discourse-in-use focuses attention simultaneously on ho6 people interact

6ith each other! the tools they use in those interactions! the social and historical conte7ts 6ithin

6hich they interact! and 6hat they concertedly create and accomplish throu"h those interactions'

The concept of 8discourse-in-use9 can be distin"uished from other definitions of discourse'

Discourse has been defined as stylistic 6ays of usin" lan"ua"e : ;! 6ritten te7t : ;! as a set

of cultural! historical! and ideolo"ical processes :cf'! <oucault! ,/=3;! amon" other definitions

:see Bloome! Carter! Christian! Otto * <aris! in press! for a discussion of definitions of

discourse;' ee :,//-; distin"uishes bet6een discourse 6ith a lo6er case 8d9 and Discourse

6ith an upper case 8D'9 The former referrin" to 6ays of usin" lan"ua"e 6ithin face-to-face

events and similar situations> the latter referrin" to broad social! cultural! and ideolo"ical

processes' 0hether one uses ee?s trope of lo6er case 8discourse9 versus upper case

8Discourse!9 ackno6led"ement needs to be made that people use lan"ua"e and other semiotic

tools 6ithin multiple layers of social conte7t and that 6ays of usin" lan"ua"e do not e7ist

distinct from broader social and historical processes' 0e use 8discourse-in-use9 to ask 6ho is

doin" 6hat 6ith 6hom! to 6hom ! 6hen! 6here! and ho6@ The concept of discourse-in-use

focuses attention on ho6 people adopt and adapt the lan"ua"e and cultural practices historically

available in response to the local! institutional! macro-social and historical situations in 6hich

they find themselves'

5n this chapter! 6e e7amine methodolo"ical 6arrants and obli"ations that the concept of

discourse-in-use provides for researchers interested in describin" and understandin" ho6 people

accomplish education' By 8accomplish education!9 6e mean ho6 people create events and

+

social institutions that are reco"niAable to themselves and others as educational events and

educational institutions' 0e vie6 the accomplishment of education as occurrin" both in

classroom and non-classroom settin"s'

0e be"in by briefly discussin" historical roots of the concept of discourse-in-use' Then!

6e discuss the material nature of discourse-in-use and the nature of the 6arrants needed to

support claims re"ardin" interpretations of discourse events' 0e follo6 the discussion of

6arrants by raisin" t6o key issues( animation of discourse and a"ency! and dividin" practices'

To illustrate the concepts 6e present! 6e e7amine a small se"ment of classroom conversation

from a seventh "rade lan"ua"e arts lesson' 5n this classroom conversation! the teacher and

students had been discussin" Sterlin" Bro6n?s poem! 8%fter 0inter'9 The conversation evolved

into a discussion of lan"ua"e variation and the particular conversational se"ment 6e use involves

discussion of 8soundin" 6hite'9

Transcript ,

Conversational se"ment from a Seventh rade )an"ua"e %rts )esson

3, Teacher 0ho can e7plain to the concept of soundin" 6hite B

3+ Maria OC 5 have an e7ample

32 Maria 0hen 5 be at lunch and 5 say liDke

31 %ndre 0hen 5 be laughs :aside;

3E Teacher F0ait a minuteF

3- Teacher 5?m sorry G

iven space limitations! the discussion is necessarily brief' <or more e7tensive discussions of

the theoretical and methodlo"ical issues 6e refer readers to Bloome et al! in press> ee!

Schiffrin! Tannen! * .amilton! +33,> > van DiHk! > 0oodak! > Iadd others hereJ'

2

Historical Roots of Discourse-in-use?

0e trace the historical roots of discourse-in-use to t6o related intellectual traditions'

,

The first derives from the literary and lin"uistic theoriAin" of Bakhtin :,/2E! ,/E2; and

Kolosinov :,/+/L,/M2; and the use of their theories in analysis of educational processes :e'"'!

;' The second derives from the ethno"raphy of communication :cf'! Bauman! ,/=->

umperA!,/=+a> umperA * .ymes!,/M+> .eath! ,/=2> .ymes!,/M1; and related intellectual

traditions such as interactional sociolin"uistics :cf'! ee! ,//-> .anks! +333> Ochs! Sche"loff! *

Thompson! ,//-; and ethnomethodolo"y :cf'! Sacks! Sche"loff * Jefferson! ,/M1; and the

evolution of these lines of intellectual inNuiry in constitutin" an educational lin"uistics :cf'!

Bloome et al! in press> CaAden! ,/==! ,//+> CaAden! Jon! * .ymes! ,/M+> reen! ,/=2> reen *

0allat! ,/=,> <oster! ,//E> .eap ,/=E! ,/==> Macbeth! +332> Mehan! ,/M/>,/=3;' These t6o

intellectual traditions focus attention on the inseparability of lan"ua"e from the conte7ts of its

use'

Roots in Literary Theory. <or Bakhtin :,/2EL,/=,; and Kolosinov :,/+/L,/M2;! conte7t

is historical' $very 6ord invokes a history of its use! both 6hat has "one before and 6hat is to

come later' Bakhtin :,/2EL,/=,; 6rites(

The living utterance, having taken meaning and shape at a particular historical

moment in a socially specific environment, cannot fail to brush up against

thousands of living dialogic threads, woven by socio-ideological consciousness

around the given object of an utterance; it cannot fail to become an active

participant in social dialogue. After all, the utterance arises out of this dialogue as

a continuation of it and as a rejoinder to it it does not approach the object from

the sidelines. (pp. 276-277)

1

But 6ords do not only reflect a history and a 8socially specific environment!9 they also refract

that history' That is! 6ords are located in a tension bet6een centripetal forces that seek to

maintain an ideolo"ical status Nuo and centrifu"al forces that seek to provoke chan"e'

#art of the historical conte7t also involves the ackno6led"ement of multiple voices!

hetero"lossia! the dialo"ue Bakhtin refers to above' These different voices and their histories

and ideolo"ies play a"ainst each other' Koices can be submer"ed and subsumed> they can

harmoniAe> they can stand out from each other and create discord> they can create dialo"ue'

Koices do not e7ist in isolation! they only stand in relationship to other voices! even if only

implicitly so' <or e7ample consider an authoritative or he"emonic discourse that makes claims

to autonomous truths' Such a discourse is one that has dismissed other voices! and imposes itself

on another person :or people;! subsumin" the person as 6ell as other voices' %n authoritative

discourse! ho6ever! should be understood not as an autonomous process but as a relationship

amon" voices! amon" people! 6ithin and amon" social institutions' 5t is similarly so 6ith a

dialo"ue' % dialo"ue is also a relationship amon" voices! people! and social institutions! a

relationship that ackno6led"es the e7istence of other voices' Bakhtin defines a dialo"ue as a

discourse that allo6s for! encoura"es! and ackno6led"es the appropriation and adaptation of

other voices' 0hereas the po6er of authoritative discourse lies in its imposition from 6ithout!

the po6er of dialo"ue lies in its mutability to become an internally persuasive discourse'

%lternatively! "iven that any use of lan"ua"e al6ays involves responses to other uses of

lan"ua"e and other voices! an ar"ument can be made that all discourses are inherently dialo"ic'

%t Nuestion is the nature of that dialo"ue! the nature of the social relationships amon" people!

amon" voices! and amon" social institutions! and the de"ree to 6hich the inherent dialo"ic nature

of a discourse is obfuscated or ackno6led"ed'

E

%lso implicit in any use of lan"ua"e are assumptions about ho6 people make their 6ay

throu"h space and time' &eferrin" to novels! Bakhtin used the term 8chronotope9 to distin"uish

different implicit assumptions about ho6 people :characters in novels; made their 6ay throu"h

space and time' <or e7ample! a prota"onist in a novel may encounter a series of adventures but

the order of these adventures is of no si"nificance and there is no assumption of chan"e in the

prota"onist over time! space! or adventures' %n alternative chronotope mi"ht assume that the

seNuence of adventures is important and contin"ent and that both the prota"onist and the 6orld

chan"e over time' Bakhtin characteriAed different literary periods as havin" different underlyin"

chronotopes'

Chronotopes are not only implicit in literary 6orks! they also e7ist in the narratives that

people use to "uide their o6n lives and evaluate the lives of others includin" the narratives that

"uide educational processes! curricular models! educational evaluation! and educational research

:cf'! Bloome * Carter! +33,! Bloome * CatA! ,//M> in press;' %lthou"h chronotopes are rarely

made e7plicit! they are not deterministic' &ather! throu"h their interactions people instantiate

and challen"e an e7tant chronotope! reconstructin" 6hat has been implicitly 8"iven'9'

%lthou"h not e7plicitly noted by Bakhtin! inherent in his and Kolosinov?s discussion of

lan"ua"e is the construct of interte7tuality! first named by Cristeva :,/=-;' 5n brief! any 6ord!

utterance! or te7t! has relationships 6ith other 6ords! utterances! and te7ts! and the

meanin"fulness and si"nificance of a 6ord! utterance! or te7t derives in part from those

interte7tual relationships' .o6ever! the interte7tual relationships are not simply "iven in the te7t

itself :althou"h there may be various lin"uistic si"ns su""estin" an interte7tual relationship! for

e7ample citations;! but rather interte7tual relationships are constructed by people in interaction

6ith each other :Bloome * $"an-&obertson! ,//2;' 5nterte7tual relationships need to be

-

proposed! reco"niAed! ackno6led"ed! and have social si"nificance :Bloome * $"an-&obertson!

,//2;'

Roots in The Ethnography of Communication and Related Intellectual Traditions. The

inseparability of lan"ua"e from its conte7ts of use is also found in the ethno"raphy of

communication and related intellectual traditions' <ocusin" on ho6 culture influences ho6

people use lan"ua"e in their everyday lives! ethno"raphers of communication and others have

e7amined variation in the lan"ua"e practices people use in their everyday lives' .o6 people

"reet each other! ar"ue! make romance! create coherence! tell stories! listen! construct and sho6

en"a"ement! Hoke! share information! form social "roups! alienate and isolate others! establish

social and cultural identities! amon" other social activities! are inseparably connected to their

culture! to their shared 6ays of actin"! thinkin"! believin"! and feelin"'

One "oal of the ethno"raphy of communication and related intellectual traditions has

been to describe the diverse lan"ua"e practices people employ across cultures' <or e7ample!

ho6 do people en"a"e in storytellin" in different ethnic cultures@ $ducational researchers

buildin" on the ethno"raphy of communication have noticed that occasionally cross-cultural

miscommunication occurs in classrooms because the lan"ua"e practices of the classroom may

differ from that of the students? home' <or e7ample! the 6ays of tellin" a story in a classroom

may be different than those in the student?s home culture :cf'! Scollon * Scollon! ,/=,>

Michaels! ,/=-;' $ven 6hen such differences are subtle! they can have ne"ative conseNuences

for the students unless the cross-cultural differences are reco"niAed and accommodated :e'"'! %u!

,/=3> <oster! ,//+;'

%nother "oal has been to describe ho6 people in interaction 6ith each other! throu"h

their face-to-face interactions create reco"niAable social and cultural practices and 6hat

M

interactional obli"ations and opportunities do these social and cultural practices have for

participants' <or e7ample! ethnomethodolo"ists have focused attention on Nuestion and ans6er

conversations and the 8rules9 for en"a"in" in such conversations both in and outside of

classrooms' 0hat are the rules for 6ho has the floor to speak and 6ho 6ill "et the ne7t turn at

talk@ .o6 do they kno6 6hen the Nuestion askin" event is over and they are movin" on to

another social practice@ <rom the perspective of an educational lin"uistics! at issue in Nuestions

such as those above is both the structure and the meanin"fulness and import of the social

practices teachers and students create throu"h their interactions' <or e7ample! researchers have

identified a pattern of classroom interaction labeled initiation-response-evaluationLfeedback :5-&-

<;' The teacher asks a Nuestion! a student responds! and the teacher evaluates the response

providin" feedback' 5n part! at issue in the identification of the 5-&-< seNuences in classrooms is

investi"ation of the opportunities and obli"ations made available throu"h 5-&-< seNuences'

&esearchers have focused attention on the comple7ity and import of 5-&-< seNuences for social

relationships bet6een teachers and students :e'"'! ;! for academic learnin" :e'"'! CaAden!

+332> Oystrand! > O?Connor * Michaels! ;! for student evaluation and assessment :e'"'!

;! for socialiAation :e'"'! ;! for classroom mana"ement :e'"'! ;! for race relations in

classrooms :e'"'! Bloome * olden! ,/ ;! and for cross-cultural communication :e'"'! CaAden!

,/ > ee! ;' 0hat social and cultural 6ork an 5-&-< seNuence does cannot be assumed or

predetermined but must be determined throu"h e7amination of the particularities of its enactment

and ho6 people! teachers and students! respond to each other'

% related "oal associated 6ith the ethno"raphy of communication and related intellectual

traditions has been to e7amine ho6 people interactionally construct specific events buildin" on

each other?s interactional behavior as they adapt e7tant lin"uistic and social practices in order to

=

create ne6 meanin"s! ne6 social relationships! and ne6 social accomplishments' 5mplicit in this

"oal is the assumption that people do not merely enact "iven social practices and do not merely

reproduce "iven systems of meanin"s' &ather! they are constantly e7ercisin" a"ency in adaptin"

the lan"ua"e and social practices "iven 6ithin a social settin" in order to address chan"in"

situations and circumstances and to create ne6 circumstances and situations' That is! people act

and react to each other :$rickson * ShultA! ,/MM;' $ducational researchers have e7amined ho6

teachers and students challen"e "iven institutional identities such as bein" labeled learnin"

disabled :e'"'! Clark! ,//2;! create learnin" opportunities :cf'! reen! ,/=2> &e7! ,///;! co-

construct failure :e'"'! McDermott! ,/=+> Bloome! #uro! * Theodorou! ,/=/;! challen"e and

redesi"n academic curriculum :e'"'! Bloome et al! in press;! amon" other educational processes'

Description Of The Interactional Processes Throuh !hich People

Concerte"l# Construct E$ents

Capturin" discourse-in-use reNuires description of the lin"uistic features people in

interaction 6ith each other use as they mutually construct an event' Capturin" those features is

not a technical matter as much as a theoretical one! and thus researchers may differ in ho6 they

define basic units of analysis! create transcripts! and define lin"uistic features :Du Bois! ,//,>

$d6ards! +33,> Ochs! ,/M/;' By lin"uistic features 6e are referrin" to the broad ran"e of

semiotic tools that people have available for communicatin" their intents and respondin" to each

other' These include verbal! nonverbal! and prosodic behavior! use and manipulation of obHects!

and the coordination of their behavior 6ith each other' umperA :,/ ; has referred to these

lin"uistic features as conte7tualiAation cues since it is throu"h these cues that people si"nal both

their intentions and 6hat the social conte7t is taken to be' #art of the obli"ation in for

/

educational researchers interested in capturin" discourse-in-use is describin" ho6 people use

conte7tualiAation cues to construct educational events! ho6 they communicate their intents and

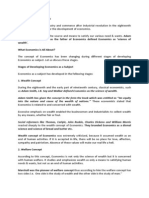

construct the social conte7ts 6ithin 6hich they interact' <or e7ample! consider Table , 6hich

sho6s the conte7tualiAation cues that define and accompany the messa"e units

+

from a small

se"ment of an instructional conversation'

Table ,

Sample of a Description of Conte7tualiAation Cues to a Transcript

%ine

&

Spea'er (essae Unit Description of Conte)tuali*ation Cues

3, Teacher 0ho can e7plain to the

concept of soundin"

6hite B

Stress on 86ho9

risin" intonation pattern peakin" at end of messa"e unit

3+ Maria OC 5 have an e7ample Stress on OC

OC acts as a place holder

<lat intonation pattern after OC

32 Maria 0hen 5 be at lunch and 5

say liDke

Stress on 80hen9

Stress on first 859

Stress on second 859

$lon"ated vo6el in 8liDke9

31 %ndre 0hen 5 be laughs Different speaker

80hen9 overlaps part of 8)iDke9

&epetition of 85 be9 intonation and style pattern

Speaker stops verbal messa"e at end

3E Teacher F0ait a minuteF reatly increased volume

Oonverbal hand Nuestions

.i"hly styliAed voice and intonation pattern

Stress on 80ait9

3- Teacher 5?m sorry G )o6er volume

Cessation of hi"hly styliAed voice and intonation

pattern

Mock intonation pattern

#ause after sorry

The description of the use of conte7tualiAation cues reNuires description of their use in

time and in relationship to 6hat has "one before and 6hat 6ill come later' That is! the

,3

meanin"fulness of a conte7tualiAation cue P a stress! a si"h! a shru"! an overlap! an intonation

pattern! etc' P is not "iven in the conte7tualiAation cue itself! but only in relationship to 6hat has

"one before and the evolvin" 6orkin" consensus amon" the interlocutors about 6hat is

happenin" at that time :cf'! reen * 0allat! ,/=,> ;'

%s teachers and student interact 6ith each other! they mutually create events 6ith

boundaries' They si"nal these boundaries to each other' There are the boundaries bet6een one

messa"e unit and another! bet6een one interactional unti and another! bet6een one activity and

another! bet6een one phase of a lesson and the ne7t! bet6een instructional time and non-

instructional time! etc' <or e7ample! in Table + the Teacher be"ins an interactional unit initiated

by a Nuestion in )ine 3,' % student responds and be"ins a narrative! all of 6hich are si"naled by

conte7tualiAation cues so that her interlocutors :the other students and the teacher; kno6 6hat

interactional behavior is e7pected of them :that is! 6hen a person is renderin" a narrative the

interlocuters are e7pected to listen 6ithout interruption unlike the previous interaction 6hich

involved student response to teacher Nuestions;' %lthou"h %ndre attempts to characteriAe his

comments as an aside :as indicated by the conte7tualiAation cues he uses;! the Teacher redefines

his aside as an interruption in the ne7t messa"e unit chan"in" the interactional unti to a ne6

conversation focusin" on the content and appropriateness of %ndre?s aside' The Teacher! Maria!

and %ndre use conte7tualiAation cues to si"nal and contest boundaries bet6een different types of

inteactional units :recitation! narrative! aside commentary! lecture;'

Boundaries are not "iven by one person! by a teacher or a student! althou"h a person may

propose a boundary' &ather! boundaries are mutually created as they must be mutually a"reed

upon' Thus! a teacher mi"ht si"nal a chan"e from one phase of a lesson to another perhaps by

,,

makin" a statement' But if the students do not respond to that si"nal and validate it! then no

transition 6ill have occurred'

The importance of boundaries is that they si"nal to interlocutors chan"es in the

interactional ri"hts and obli"ations they have to6ard each other and they si"nal potential chan"es

in 6hat is happenin" and the shared interpretive frame6orks that mi"ht be employed at that time'

<or e7ample! as a classroom lesson moves from a series of 5-&-< seNuences to a narrative! the

ri"hts and obli"ations for participation for the teacher and the students chan"e and the

interpretive frame6ork for evaluatin" behavior and content chan"es as 6ell' Thus! in Table +!

%ndre?s behavior 6hich mi"ht have been acceptable durin" the more free form Nuestion-ans6er

discussion 6as not appropriate once Maria be"an her narrative'

Description! therefore! is not a process of codin" communicative behavior! but rather one

of situatin" behavior 6ithin the flo6 of social interaction' The meanin"fulness of any

communicative behavior or of any stream or seNuence of behavior is not found 6ithin itself but

in its use and import 6ithin the flo6 of social interaction' #eople en"a"ed in interaction 6ith

each other must constantly monitor 6hat is happenin" in order to assi"n meanin"fulness to

communicative behavior' Similarly! 6hatever claims researchers mi"ht make about 6hat is

happenin" at any particular moment in an educational event need to be ar"ued in terms of the use

and import of communicative behavior 6ithin the conte7t of the flo6 of social interaction'

Qet! even such situated claims and ar"uments need to be tentative as the meanin" and

import of any specific moment 6ithin an on"oin" event can be redefined later :Bloome! ,/ ;' %

particular comment made by a student or a particular series of e7chan"es bet6een a teacher and a

student can be interpreted one 6ay by interlocutors at the time of their occurrence! but later they

can be referenced and the meanin" of that behavior or series of e7chan"es rene"otiated' <or

,+

e7ample! Maria?s use of the habital be form in line 32 in Table + :80hen 5 be at lunch '''9; is

first framed by %ndre as either an inferior 6ay of speakin" or as ironic :since Maria is

complainin" of bein" accused of 8speakin" 6hite9 6hen she is usin" a feature of %frican

%merican )an"ua"e; but later in the instructional conversation the Teacher makes clear that she

uses the habitual be! that it is used by educated people! and that use of the use of the habitual be

is not 6ron" or inappropriate' 5n brief! the Teacher reconte7tualiAes the lin"uistic behavior' 5n

sum! any communicative behavior can be reconte7tualiAed' Meanin" is never determinate'

Oor is the meanin"fulness of any communicative behavior monolithic' <irst! althou"h

interlocutors may have established a 6orkin" consensus for interpretin" each other?s behavior

6ithin a particular event! they may have only done so at a surface level' $ach person may be

brin"in" to the event interpretive frame6orks from their o6n histories or cultural back"rounds

that are not shared' %nd althou"h the communicative behaviors each produces is sufficient to

create an on"oin" and coherent event! beyond the production of the event itself! the interpretation

of 6hat occurred durin" that event varies 6idely' Thus! researchers! like the people en"a"ed in

the event themselves! must distin"uish bet6een the production of the event itself :6hat Bloome!

#uro! * Theodorou! ,/=M! call procedural display; and the meanin"fulness of that event on

multiple levels'

<or e7ample! one of the institutional obli"ations of schools is to produce events that look like

8schoolin"'9 The conversation in Table + looks like 8schoolin"'9 The teacher is askin"

Nuestions! standin" mostly at the front of the class! the students are sittin" at their desks! raisin"

their hands for a turn at talk! and discussin" a poem introduced by the teacher earlier in the

lesson' 5n part! the meanin"fulness of an event is in its location 6ithin a series of events'

,2

Sometimes interlocutors si"nal the series of events in 6hich they are embeddin" an event in they

are participatin"' But sometimes the broader series of events is assumed and interlocutors only

need to si"nal the broader series of events if they detect confusion or disa"reement' But it is also

the case that the series of events 6hich conte7tualiAes any particular event can be disputed and

contested' %s a result! the meanin"fulness of an event or of a communicative behavior 6ithin an

event can vary even amon" those in interaction 6ith each other' <or e7ample! in the event

sho6n in Table + involves an interruption to Maria?s story by %ndre and opens a Nuestion about

the le"itimacy of the habital-be form :and more "enerally! the le"itimacy of %frican %merican

)an"ua"e;' Maria is locatin" the topic :8speakin" 6hite!9 usin" the habitual-be! %frican

%merican )an"ua"e; 6ithin her o6n e7periences :6hen she is at lunch;' %ndre relocates it

6ithin the conte7t of a peer "roup classroom conversation' The Teacher relocates the

interruption and the topic 6ithin the broader topic of understandin" lan"ua"e variation and then

later in the lesson she uses their discussion of the habitual-be to raise Nuestions about the poem

they had read and at the end of the lesson she uses the interruption to raise Nuestions about the

ethics of interpretation' She tells the students at the end of the lesson(

a lot of you are makin" e7cellent comments but they are devoid of you as a

person' 5t?s very easy to make "eneraliAations about people or about other people

6hen you?re able to take yourself out of it! But 6hen you put yourself back into

your statements! put yourself in relationship to your comments you?re makin"!

and then see if the comment still 6orks

5n brief! the Teacher?s comments at the end of the lesson propose a reinterpretation of the

instructional conversation that has occurred on that day and previously in their classroom' She is

proposin" a reinterpretation about 6hat counts as valid kno6led"e' 0hether the Teacher?s

,1

proposed reinterpretation is interactionally validated cannot be kno6n at that time as the lesson

ends and the students leave' The task for the researcher is to e7amine subseNuent events! such as

instructional conversations the ne7t day in the lan"ua"e arts classroom for public validation!

6hether e7plicit or implicit! of the teacher?s proposal about 6hat counts as valid kno6led"e'

More "enerally stated! the task for a researcher interested in the meanin"fulness and import of

any educational event is to build a data-based ar"ument in 6ays similar to that 6hich

interlocutors 6ould use to assi"n meanin"fulness yet kno6in" that meanin" is indeterminate!

multiple! and not necessarily fully shared amon" the interlocutors'

(aterial Nature an" Orani*ation of Discourse Practices

Discourse-in-use is material and reNuires "eo"raphy' The 6ords! prosody! nonverbal

behaviors! and manipulation of obHects are all material! they have substance' So! too! the bodies

of those en"a"ed in interaction' ConseNuently! discourse-in-use is subHect to all of those

processes associated 6ith material production! distribution! and consumption'

Consider the instructional conversations that occur in classrooms' Students and teacher

enter into a physical space :a classroom; that has been pre-established 6ith a particular siAe!

li"htin"! and "iven furniture Some elementary classrooms include alcoves Hust bi" enou"h for a

table of si7 to seven students and a teacher' $ven the people and the types of people have been

predetermined' The number of people in the classroom is a material condition influencin" ho6

people can en"a"e in discourse' 5mplicit in this classroom "eo"raphy are ideolo"ical

assumptions about the kinds of social and cultural practices! the discourse practices! that 6ill

occur there and the space has been manufactured to encoura"e those social and cultural practices'

Similarly so! time has been pre-established' 5t is not Hust that there is an official be"innin" and

,E

endin" time! rather for most teachers the school day is previously se"mented! and pre-determined

distinctions are instructional time and play time :e'"'! recess! lunch;' Calendar time is also pre-

determined' $valuation schemes also define time( by a certain point in the year! the students are

e7pected to have "one throu"h particular curriculum units and to have demonstrated competence

in predetermined skills'

The social and cultural practices in 6hich teachers and students are to en"a"e are also

"iven materially' Throu"h the provision of te7tbooks! teacher "uides! instructional materials

:e'"'! paper! pencils! soft6are;! the location of blackboards! etc'! particular social practices for

interaction bet6een teachers and students are encoura"ed' <urther! teachers! students! and others

:e'"'! administrators! parents; hold e7pectations for 6hat social and cultural practices 6ill occur

in the classroom space as they define education throu"h the instantiation of those social and

cultural practices' 5f those e7pectations are not fulfilled! they 6ill react and their reactions are

part of the material conditions of classroom discourse'

5n brief! teachers and students step into a "iven chronotope and a set of "iven social and

cultural practices defined as education that are materially manifest' They step into a "iven

discourse' Their history and the historical conte7t of their discourse-in-use does not be"in 6ith

their first day of school! but rather 6ith deeper roots and materially so' One of the obli"ations of

educational researchers interested in discourse-in-use in classroom settin"s is to describe!

interpret! and e7plain the production of the material conditions of classroom discourse'

Qet! despite the "iven material conditions! teachers and students are not dependent

variables' %lthou"h the material conditions may constrain 6hat they can do and ho6 they mi"ht

interact 6ith each other :or more positively stated! provide encoura"ement and affordances to

en"a"e in particular social and cultural practices;! people also act upon those material conditions!

,-

adapt "iven social and cultural practices! and create events that in small measure or lar"e esche6

the social and cultural practices "iven' %s a history of such events is made! that history may

become part of the material conditions of classroom discourse' 5t is not Hust that the "iven space

mi"ht be re-arran"ed or e7panded :e'"'! use of the hall6ay;! and divisions of time redefined! but

that the social and cultural practices that the teachers! students! and others held for definin"

education mi"ht evolve and that the e7pectations embodied in their reactions to each other have

chan"ed'

Consider the classroom conversation in Table+' The lesson be"an 6ith a readin" of a

poem and discussion of 6hat happened in the poem' .o6ever! rather than focus attention on the

poem itself! the teacher and the students use the poem as a prop to e7plore their o6n lives> in this

case! their lives as racialiAed people 6ho speak varieties of $n"lish labeled 86hite!9 and L or

8Black9' They have adapted the traditional poetry lesson 6hich focuses on the meanin" of the

poem 6ithout losin" the appearance of en"a"in" in a traditional classroom poetry lesson :e'"'!

presentin" a poem! a teacher-led discussion! related home6ork assi"nments! hand-raisin"! etc';'

Thus! one obli"ation of the educational researcher interested in describin"! interpretin"! and

e7plainin" discourse-in-use in educational settin"s is to capture the adaptation and evolution of

the material conditions of classroom discourse over time' The cross-sectional study of discourse-

in-use is a non-seNuitor'

%t issue! ho6ever! is not Hust an a"enda 6ith re"ard to documentin" the material

conditions of discourse-in-use' Since discourse itself is material! e7istin" both in the resources at

hand and in the conte7tualiAation cues of people in interaction use! a record can be made of the

material enactment of discourse-in-use' That record needs to sho6 ho6 people acted and reacted

to each other' 5t is throu"h the careful description of the material enactment of the event! of the

,M

discourse-in-use in that event as it constitutes the event! that educational researchers are

6arranted in makin" claims about 6hat is happenin" in that event' The key for educational

researchers interested in constructin" interpretations of an event that lie close to the

interpretations of the people in that event is to call upon the same or similar frames of reference

as the people there' Since the people in that event need to make clear to each other their

e7pectations for the interpretive frame6orks to be used in assi"nin" meanin" to the event and

since they si"nal those intentions materially! those material cues are also visible to researchers of

that event' Claims! therefore! to the interpretation of discourse events are 6arranted by

description of the material construction of that event as it reveals ho6 people in that event! both

individually and collectively! built an interpretation of 6hat 6as occurrin"'

+ni,ation of Discourse an" +enc#

The animation of discourse refers to conceptions of discourse that treat it as if it 6ere

itself a person or a"ent' Such animation occurs 6hen discourse is vie6ed as capturin" a person

or as positionin" a person' <or e7ample! the discourse of schoolin" forces people into the

cate"ory of 8teacher9 or 8student'9 iven the ubiNuitous nature of these cate"ories in the

discourse used across schools in 0estern countries! it 6ould be impossible to assi"n such use to

an individual or to a "roup' 5ndeed! 6hat is prime in such uses of discourse is that they appear

ubiNuitous! 6ithout a specific a"ent! and 8natural'9 Oatural refers to bein" taken-for-"ranted! an

obvious truth! common sense! and uncontested' Of course! such cate"ories and such a discourse

may not at all be uncontested! alternatives may e7ist or could be ima"ined' #art of 6hat is

po6erful about the naturaliAation of a discourse is that refusal to adopt the discourse! and ho6 it

,=

captures people! can be taken by others as a si"n of lack of common sense! a denial of truth! and

in some cases! as patholo"y or mental illness'

<rom the point-of-vie6 of discourse-in-use! the Nuestion to ask about animated

discourses is not their ori"in! but 6ho is usin" that animated discourse to do 6hat! to 6hom!

6hen! 6here! and 6ith 6hat conseNuences' &eturnin" to the discourse of schoolin"! in a

particular school district! school! or classroom! people may use the discourse of schoolin" and its

cate"ories of teacher and student to create a kno6led"e hierarchy and a set of social relationships

amon" people' Once established! school officials can locate kno6led"e and the presti"e and

po6er that accompanies it in the school and they can define the communities served by the

school as i"norant and deficit' $ven if there is opposition to the 6ay that the animated discourse

is used! by invokin" it! people can establish the terms of debate! values! and 6hat is assumed to

be common sense and rational'

<or e7ample! in the classroom lesson described earlier! one of the students invokes the

discourse of proper and improper lan"ua"e! a discourse also invoked by the formal curriculum of

prescriptive "rammar' The student invokes that discourse as if it Hust e7ists! as if it is 8natural9

and to be taken for "ranted that there is a proper and improper 6ay of usin" lan"ua"e' The

discourse of proopoer and improper captures people! as if the discourse iteself 6ere an a"ent' 5n

the lesson! the teacher responds to the students invokin" of such a discourse by problematiAin"

the terms proper and improper' She Nuestions! 8OC! 0hat is proper and 6hat is slan"@ .elp me

outF9 %nd similarly in Table +! she problematiAes the notion that the habitual be

%nimated discourses are subHect to the same processes of adaptation that 6ere discussed

earlier' %s people act and react to each other! they not only respond to animated discourses they

adapt and refract them' <or e7ample! reconsider the discourse of schoolin" and its cate"ories of

,/

teacher and student and the implied hierarchy in those terms' 5n some classrooms! teachers 6ill

redefine the assi"nment of those terms statin" that 85n this classroom! 6e are all teachers and all

students'9 Other teachers mi"ht redefine their role as a teacher from that of dispensin"

kno6led"e to that of facilitatin" kno6led"e acNuisition processes' 0hat is at issue here is not

specific responses to the cate"ories of teacher and student! but rather that people are not simply

8captured9 by a discourse' 0hile some may adopt an animated discourse! others may modify!

adapt! or transform such a discourse throu"h their interactions 6ith others' Some may do so

deliberately and label their actions so as part of a resistance to that discourse! its values! and ho6

it structures social relationship! others may do so implicitly and 6hile the adaptations may be

substantial they 6ould not necessarily label their actions as resistance' &e"ardless! animated

discourses do not e7ist outside of the a"ency of people 6ho use them'

Discourse-in-Use an" the !or' of Di$i"in Practices

-

Dividin" practices create cate"ories for or"aniAin" and controllin" people and subHectin"

them to the "oals of a social institution' Thus! social institutions such as schools! families!

churches! courts! and health care! all use dividin" practices to create le"itimate L ri"hteous and

ille"itimate L errant people that Hustify the e7istence of the social institution( the educated and the

i"norant! relatives and stran"ers! believers and heretics! the la6-abidin" and the criminal! the

sane and insane! etc' Such dividin" practices can be codified P e'"'! students attendin" school

versus truant students P or part of a 8folk9 cate"orical system P e'"'! "ood students versus bad

students' Dividin" practices provide a rationale for the social institution to en"a"e in activities

that protect the le"itimate from the ille"itimate and to convert the errant to the ri"hteous'

+3

The po6er of a discourse! in part! lies in its dividin" practices and in makin" those

dividin" practices appear 8natural'9 Once the dividin" practices are taken as common sense! as

obvious! and as e7istin" 6ithout alternative! there is no need to control people throu"h physical

coercion' &ather! people 6ill act in accordance 6ith the 8truth9 of the social institution and its

dividin" practice' %ll that remains to be debated is ho6 to enact that 8truth'9

0ith re"ard to discourse-in-use! educational researchers cannot limit their investi"ations

to identifyin" and describin" the dividin" practices of educational discourses' &ather! attention

needs to be focused on 6ho is usin" those dividin" practices! to do 6hat! to 6hom! 6hen and

6here' 5n brief! ho6 is the 8truth9 of that discourse and its dividin" practices enacted' Such a

vie6 of classroom discourse redefines a number of educational processes' <or e7ample! rather

than define academic learnin" and success as an achievement and failure as lack of achievement!

both success and failure are vie6ed as social achievements :see ;' The 8"ood9 students

e7ists :and obtains herLhis privile"es; only because the 8bad9 student is Hu7taposed' <or

e7ample! the teacher asks the students 6hether there is a proper and improper 6ay of speakin" or

6hether people 8codes6itch9 in different situations' By doin" so! she challen"es the dividin"

practices the students have assumed as natural'

5n addition to describin" the enactment of dividin" practices! attention needs to be paid to

ho6 people! throu"h their interactions 6ith each other! are adaptin" and transformin" those

dividin" practices' Such adaptations mi"ht be acts of resistance! others mi"ht not be defined as

such' <or e7ample! some teachers refuse to define their students as 8"ood9 or 8bad'9 Some

schools refuse to "ives "rades' They en"a"e in such practices as overt acts of resistance to the

normative discourse of schoolin"' Some teachers redesi"n the curriculum and the evaluation

system so that every student in their classroom is successful! definin" success not in terms of its

+,

opposition to failure but as a developmental process' Such actions may not be overt acts of

resistance! nonetheless such acts adapt and transform the dividin" practices of school discourse'

Thus! part of the obli"ation for educational researchers interested in discourse-in-use is to

describe the adaptations of dividin" practices both in those classrooms that are e7plicitly

resistant and in those that make no claim to resistance'

.inal Co,,ents/ Discourse-in-Use as a Situate" Process

The Nuestion to ask about discourse is not 6hether it is 6ritten or spoken! discourse or

Discourse! animated or other6ise! verbal or non-verbal! ubiNuitous or confined! adopted or

adapted P discourse is al6ays all of these' The Nuestion to ask is 6ho is doin" 6hat! 6ith 6hom

to 6hom! to 6hat conseNuence! 6hen and 6here' The 86hen and 6here9 is critical as it situates

discourse-in-use as an historical and interpersonal process' %s $rickson and ShultA :,/MM;

pointed out over t6o decades a"o! people are the conte7t for each other' The obli"ation and

6arrant for educational researchers interested in ho6 people create education is to trace!

moment-by-moment! action by action! response by response! and refraction by refraction! ho6

people use the lin"uistic tools they have available and the material resources at hand to adopt and

adapt e7tant discourse practices as they define their social relationships! social identities!

kno6led"e! and the acNuisition of kno6led"e' Such an obli"ation includes the interte7tual and

interconte7tual nature of any event and the dialo"ic relationship of the event 6ith other events'

But! rather than create a description that merely serves as an illustration of e7tant social theory!

the obli"ation is to create a description and interpretation 6hose e7planation lies close to the

meanin"fulness of the event produced by the people involved' Such an e7planation does not

++

esche6 social theory! but redefines social theory as a situated process that is both particular and

historical'

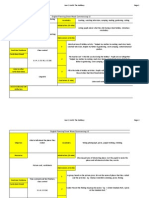

5llustration of Messa"e Unit Boundaries Kia Conte7tualiAation Cues

%ine

&

Spea'er (essae

Unit

Conte)tuali*ation

Cues Use" to

Deter,ine (essae

Unit 0oun"aries

Interpretation of

Conte)tuali*ation Cues in

I"entif#in (essae Unit

0oun"aries

3, Teacher 0ho can

e7plain to

the concept

of soundin"

6hiteB

Stress on 86ho9

risin" intonation

pattern peekin" at end

of messa"e unit

Ms' 0ilson "ives up

floor

Stress on 86ho9 indicates

be"innin" of the messa"e unit>

risin" intonation pattern si"nals

Nuestion and lack of speaker

desi"nation allo6s students to

compete for the ne7t turn

3+ Maria OC 5 have

an e7ample

Stress on OC

OC acts as a place

holder

<lat intonation pattern

after OC

no pause after end

Stress on OC si"nals both a

be"innin" to the messa"e unit and

a claim on speakin" ri"hts> flat

intonation pattern and lack of

pause at end si"nal maintains of

turn-at-talk

32 Maria 0hen 5 be

at lunch

and 5 say

liDke

Stress on 80hen9

Stress on first 859

Stress on second 859

$lon"ated vo6el in

8liDke9

Use of syntactic form

to indicate a receurrent

event

Stress on 86hen9 si"nals shift to a

ne6 messa"e unit> elon"ated vo6el

in 8liDke9 su""ests that either more

is comin" in this messa"e unit or

speaker is holdin" the floor for the

ne7t turn-at-talk' Syntactic form

si"nals the be"innin" of a narrative

and therefore ri"hts to consecutive

turns at talk'

31 %ndre 0hen 5 be

laughs

Different speaker

80hen9 overlaps part

of 8)iDke9

&epetition of 85 be9

Speaker stops verbal

messa"e at end

Stylistic intonation

pattern

Messa"e unit is part of a side

conversation> timin" of 80hen9 to

overlap 8liDke9 in previous

messa"e unit su""ests either

8liDke9 6as interpreted as end of a

messa"e unit and that the floor 6as

open or that Maria has violated

rules for maintainin" the floor or

%ndre has violated rules for "ettin"

the floor> lau"hter is not a si"nal of

+2

%ine

&

Spea'er (essae

Unit

Conte)tuali*ation

Cues Use" to

Deter,ine (essae

Unit 0oun"aries

Interpretation of

Conte)tuali*ation Cues in

I"entif#in (essae Unit

0oun"aries

Ruasi-6hisper volume maintainin" the floor or of a

continuin" messa"e unit

3E Teacher F0ait a

minuteF

reatly increased

volume

Oonverbal hand

Nuestions

.i"hly styliAed voice

and intonation

pattern

Stress on 80ait9

5nterrupts both %ndre and Maria!

reasserts control of turn-takin" and

conversational floor> styliAed

pattern indicates shifts to another

topic or type of conversation and

mutes the 8offense9 of interruptin">

stess on 86ait9 brin"s students?

talk to a stop! takes the form of a

command

3- Teacher )o6er volume

Cessation of hi"hly

styliAed voice and

intonation pattern

Mock intonation

pattern

#ause after sorry

Shift in tone! volume! and style

si"nals shift to a different type of

interactional unit' The mock

rendition of 85?m sorry9 allo6s

politeness form made necessary by

interruptin" the conversation but

makes clear doin" so is not really a

violation of the teacher?s 8ri"hts?

to control the floor and indicates

that %ndre?s interruption 6as

inappropriate' Si"nals the

be"innin" of the teacher?s

commentary on %ndre?s

comments'

+1

&eferences

%u! C' :,/=3;' #articipation structures in a readin" lesson 6ith .a6aiian children' Anthropology

and Education Quarterly, 11, +! /,-,,E'

Bakhtin! M' :,/2EL,/=, trans';' The dialogic imagination. %ustin! TS( University of Te7as

#ress'

Bakhtin! M' :,/E2L,/=- trans';' The problem of speech "enres' 5n C' $merson * M' .olNuist

:eds'; Speech genres and other late essays. %ustin! TS( University of Te7as #ress'

Bauman! &' :,/=-;' Story, performance, and eent! Conte"tual studies of oral narratie'

Cambrid"e! $n"land( Cambrid"e University #ress'

Bloome! D'! * Carter! S' :+33,;' )ists in &eadin" $ducation &eform' Theory #nto $ractice. %&,

2! ,E3-,EM'

Bloome! D'! Carter! S'! Christian! B'! Otto! S'! * <aris! O' :in press;' Discourse analysis ' the

study of classroom language ' literacy eents ( A microethnographic perspectie.

Bloome! D'! * $"an-&obertson! %' :,//2;' The social construction of interte7tuality and

classroom readin" and 6ritin"' Reading Research Quarterly, )*, 1! 232-222'

Bloome! D'! #uro! #' * Theodorou! $' :,/=/; #rocedural display and classroom lessons'

Curriculum #n+uiry, 1,, 2! +-E-+/,'

CaAden! C' :,/==;' Classroom discourse! The language of teaching and learning' #ortsmouth!

O.( .einemann'

CaAden! C' :,//+;' -hole language plus! Essays on literacy in the ..S' and Oe6 Tealand' Oe6

Qork( Teachers Colle"e #ress'

+E

CaAden! C'! John! K'! * .ymes! D' :eds'; :,/M+;' /unctions of language in the classroom. Oe6

Qork> Teachers Colle"e #ress'

Clar'1 + 2344-56 Associative Engines: Connections, concepts, and representational

change. Ca,7ri"e1 Enlan"/ Ca,7ri"e Uni$ersit# Press

!HICH ONE? + OR S Clar' or neither?

Clar'1 S61 Cote1 C61 8a*9ue*1 +61 : !essi1 ;6 2344-56 Life as teenagers in the nineties:

Groing up in !pringfield, "A6 Sprinfiel"1 (+/ <erena Co,,unit# !ritin Clu7

Press6

Du Bois! J' 0' :,//,;' Transcription desi"n principles for spoken discourse research'

$ragmatics, ,! ,! M,-,3-'

$d6ards! J' %' :+33,;' The transcription of discourse' 5n D' Schiffrin! D' Tannen! * .'

.amilton :eds'; The hand0oo1 of discourse analysis. :pp' 2+,-21=;' Malden! M%(

Black6ell'

$rickson! <'! * ShultA! J' :,/MM;' 0hen is a conte7t@ 2e3sletter of the 4a0oratory for

Comparatie 5uman Cognition, 1, +! E-,+'DDDD-

<oster! M' :,//+;' Sociolin"uistics and the %frican-%merican community( 5mplications for

literacy' O$$D &$ST O< &$<

<oster! M' :,//E;' Talkin" that talk( The lan"ua"e of control! curriculum and critiNue'

4inguistics and Education, 6! +! ,+/-,E3'

<oucault! M' :,/=3;' $o3er71no3ledge! Selected interie3s and other 3ritings, 1,6)81,66'

I$dited by C' ordonJ' Oe6 Qork( #antheon Books'

ee! J' #' :,//-;' Social linguistics and literacies! #deology in discourses. +nd' ed' )ondon(

Taylor and <rancis'

<ee1 =6P6 234445 6An Introduction to #iscourse Analysis: Theory and "ethod. In Press6

+-

<ee1 =6P6 2>???56 The Ne@ %iterac# Stu"ies/ .ro, Asociall# situate"B to the @or' of the

social6 In D6 0arton1 (6 Ha,ilton1 : R6 I$anic 2e"s65 !ituated literacies: Reading and

riting in conte$t 2pp6 3C?-34D56 %on"on/ Routle"e6

reen! J' :,/=2;' $7plorin" classroom discourse( )in"uistic perspectives on teachin"-learnin"

processes' Educational $sychologist, ,=! 2! ,=3-,//'

reen! J'! * 0allat! C' :eds;' :,/=,;' Ethnography and language in educational settings.

Oor6ood! OJ( %ble7 #ublishin" Corp'

umperA! J' :,/=+;' Discourse strategies' Cambrid"e( Cambrid"e University #ress' :a;

umperA! J'! * .ymes! D' :$ds'; :,/M+;' Directions in sociolinguistics! The ethnography of

communication. Oe6 Qork( .olt! &inehart * 0inston'

.anks! 0' :+333;' #nterte"ts! -ritings on language, utterance, and conte"t' )anham! MD(

&o6an * )ittlefield #ublishers! 5nc'

.eath! S' :,/=2;' -ays 3ith 3ords. Cambrid"e! UC( Cambrid"e University #ress'

.eap! J' :,/=E;' Discourse in the production of classroom kno6led"e( &eadin" lessons'

Curriculum #n+uiry, 19, 2! +1E-+M/'

.eap! J' :,/==;' On task in classroom discourse' 4inguistics and Education, 1, +! ,MM-,/='

.ymes! D' :,/M1;' The foundations of sociolinguistics! Sociolinguistic ethnography'

#hiladelphia( University of #ennsylvania #ress'

Cristeva! J' :,/=-;' 0ord! dialo"ue! and novel' 5n T' Moi :ed'; The :ristea reader' :pp' 21--,;'

O7ford( Basil Black6ell'

Macbeth! Dou"las :+332;' .u"h Mehan?s 8)earnin" lessons9 &econsidered( On the difference

bet6een the naturalistic and critical analysis of classroom discourse' American

Educational Research ;ournal, %&, ,! +2/-+=3'

+M

McDermott! &'! * .ood! )' :,/=+;' 5nstitutional psycholo"y and the ethno"raphy of schoolin"'

5n #' ilmore * %' latthorn :eds;' Children in and out of school. :pp' +2+-+1/;'

0ashin"ton! D'C'( Center for %pplied )in"uistics'

Mehan! .' :,/M/;' 4earning lessons. Cambrid"e! M%( .arvard University #ress'

Mehan! .' :,/=3;' The competent student' Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 11! 2! ,2,-

,E+'

Michaels! S' :,/=-;' Oarrative presentations( %n oral preparation for literacy 6ith first "raders'

5n J' Cook-umperA :$d'; The social construction of literacy' Cambrid"e! $n"land(

Cambrid"e University #ress'

Ochs! $' :,/M/;' Transcription as theory' 5n $' Ochs * B'B'' Schieffelin :eds'; Deelopmental

pragmatics. :12-M+;' Oe6 Qork( %cademic #ress' '

Ochs! $'! Sche"loff! $'%'! * Thompson! S'%' :eds'; :,//-;' #nteraction and grammar. Oe6

Qork> Cambrid"e University #ress'

&e7! )'%'! * Mc$achen! D' :,///;' 5f anythin" is odd! inappropriate! confusin"! or borin"! its

probably important' Research in the Teaching of English, <%, ,! -E-,+/'

Sacks! .'! Sche"loff! $'! * Jefferson! ' :,/M1;' % simplist systematics for the or"aniAation of

turn takin" in conversation' 4anguage, 9&, 1! -/--M2E'

Scollon! &'! * Scollon! S' :,/=,;' 2arratie7literacy and face in interethnic communication.

Oor6ood! OJ( %ble7 #ublishin" Corporation'

Schiffrin! D'! Tannen! D'! * .amilton! .' :eds'; :+33,;' The hand0oo1 of discourse analysis.

Malden! M%( Black6ell'

Kolosinov! K' :,/+/ L ,/M2 trans';' Mar"ism and the philosophy of language' :trans' )' MateHka

* 5' Titunik;' Cambrid"e! M%( .arvard University #ress'

+=

,

The tracin" of intellectual traditions is not a linear or determinate process' Thus! the intellectual traditions of the concept

of 8discourse-in-use9 can be traced more broadly to include the philosophy of lan"ua"e :e'"'! 0itt"enstein! > 0illiams! ;!

social and cultural anthropolo"y :e'"'! BoaA! > Malino6ski! ;! lin"uistics :e'"'! <irth! > Sapir! > 0horf! ;! and the

sociolo"y of lan"ua"e :Bernstein! > <ishman! ;' 5n this chapter 6e provide one startin" point! amon" others! for

e7aminin" the 8lo"ics-of-inNuiry9 :cf'! ee * reen! ; related to 8discourse-in-use'9 <or other startin" points! see ee :

;! Iadd more hereJ'

+

reen and 0allat :,/=,; define a 8messa"e unit9 as the minimal unit of conversation'

2

%lthou"h numerous scholars have discussed dividin" practices! the discussion in this section builds on <oucault?s : ;

discussion of dividin" practices'

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Research Project Report On Marketing Strategies of AirtelDocument86 pagesResearch Project Report On Marketing Strategies of Airtelnajakat67% (3)

- The Rite of The General Funeral PrayersDocument8 pagesThe Rite of The General Funeral PrayersramezmikhailNo ratings yet

- Ccna Lab ManualDocument109 pagesCcna Lab ManualJoemon Jose100% (8)

- The Song of Solomon A Study of Love Sex Marriage and Romance by Tommy NelsonDocument50 pagesThe Song of Solomon A Study of Love Sex Marriage and Romance by Tommy NelsonDeoGratius KiberuNo ratings yet

- Managerial EconomicsDocument11 pagesManagerial EconomicsnajakatNo ratings yet

- G.B. Technical University Lucknow: Syllabus For Session 2013-14Document51 pagesG.B. Technical University Lucknow: Syllabus For Session 2013-14durgeshagnihotriNo ratings yet

- Square Trick 1: Square of A Number Ending in 5: ConditionDocument1 pageSquare Trick 1: Square of A Number Ending in 5: ConditionnajakatNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Economics: (A) What Economics Is All About ?Document16 pagesIntroduction To Economics: (A) What Economics Is All About ?Smriti JoshiNo ratings yet

- DissertationDocument7 pagesDissertationnajakatNo ratings yet

- E 1732Document542 pagesE 1732Kishor KumarNo ratings yet

- CocacolaDocument71 pagesCocacolaMohd SabirNo ratings yet

- GE Healthcare: 5 1 0 (K) Premarket Notification SubmissionDocument15 pagesGE Healthcare: 5 1 0 (K) Premarket Notification SubmissionnajakatNo ratings yet

- Ivita Accesories Patient Monitors List PriceDocument10 pagesIvita Accesories Patient Monitors List PricenajakatNo ratings yet

- MembersDocument6 pagesMembersnajakatNo ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction Level Toward Compaq LaptopDocument67 pagesCustomer Satisfaction Level Toward Compaq LaptopnajakatNo ratings yet

- Headquarters ITC Green Centre 10 Institutional Area, Sector 32Document1 pageHeadquarters ITC Green Centre 10 Institutional Area, Sector 32najakatNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behavior On Purchase of LaptopDocument20 pagesConsumer Behavior On Purchase of LaptopSatheesh Chandra Thipparthi80% (5)

- Godrej & Boyce Mfg. Co. Ltd. Application Form: Recent Photograph (In Professional Attire)Document3 pagesGodrej & Boyce Mfg. Co. Ltd. Application Form: Recent Photograph (In Professional Attire)Avinash PatelNo ratings yet

- Godrej & Boyce Mfg. Co. Ltd. Application Form: Recent Photograph (In Professional Attire)Document3 pagesGodrej & Boyce Mfg. Co. Ltd. Application Form: Recent Photograph (In Professional Attire)Avinash PatelNo ratings yet

- Project On Apollo Tyres LTD For PCRDocument92 pagesProject On Apollo Tyres LTD For PCRanand jai86% (14)

- Project Report On Performance AppraisalDocument79 pagesProject Report On Performance AppraisalnajakatNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 NotesDocument7 pagesChapter 10 NotesnajakatNo ratings yet

- J.Venkatesh. Training & Development Practices in ICICI BankDocument80 pagesJ.Venkatesh. Training & Development Practices in ICICI Bankvenkat79% (14)

- Paper 07Document8 pagesPaper 07Ooi Wan ShengNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Consumers' Laptop PurchasesDocument9 pagesFactors Influencing Consumers' Laptop PurchasesdearmanuNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Consumers' Laptop PurchasesDocument9 pagesFactors Influencing Consumers' Laptop PurchasesdearmanuNo ratings yet

- Yassmin Mohamed Gamal C.VDocument3 pagesYassmin Mohamed Gamal C.VkhaledNo ratings yet

- 11.chapter 2 RRLDocument10 pages11.chapter 2 RRLJoshua alex BudomoNo ratings yet

- The Long TunnelDocument5 pagesThe Long TunnelCătă Sicoe0% (1)

- Sublist 2Document2 pagesSublist 2Alan YuanNo ratings yet

- Produce and Evaluate A Creative Text-Based Presentation (Statement T-Shirt) Using Design Principle and Elements (MIL11/12TIMDocument5 pagesProduce and Evaluate A Creative Text-Based Presentation (Statement T-Shirt) Using Design Principle and Elements (MIL11/12TIMestrina bailonNo ratings yet

- Avoiding WordinessDocument18 pagesAvoiding WordinesstimurhunNo ratings yet

- Adjectives Group 1 Comparative and Superlative FormsDocument2 pagesAdjectives Group 1 Comparative and Superlative FormsBùi Quang TrânNo ratings yet

- Noun Group StructureDocument23 pagesNoun Group StructureTAMARA ANGELA MANURUNGNo ratings yet

- Installation Microsoft Visio and Project2021Document19 pagesInstallation Microsoft Visio and Project2021presto prestoNo ratings yet

- PC Imc300Document154 pagesPC Imc300JorgeNo ratings yet

- Bac Info 2020 Testul 1Document5 pagesBac Info 2020 Testul 1Silviu LNo ratings yet

- IO Planning in EDI Systems: Cadence Design Systems, IncDocument13 pagesIO Planning in EDI Systems: Cadence Design Systems, Incswams_suni647No ratings yet

- The Present AgeDocument5 pagesThe Present AgeThomas MoranNo ratings yet

- T. Romer The Problem of The Hexateuch in PDFDocument26 pagesT. Romer The Problem of The Hexateuch in PDFJorge Yecid Triana RodriguezNo ratings yet

- FRIENDSHIPDocument34 pagesFRIENDSHIPKabul Fika PoenyaNo ratings yet

- The Byzantines Averil Cameron-PrefaceDocument4 pagesThe Byzantines Averil Cameron-PrefaceKatma Vue0% (1)

- Ingrid Gross Resume 2023Document2 pagesIngrid Gross Resume 2023api-438486704No ratings yet

- Turețchi GabrielDocument2 pagesTurețchi Gabrielalex cozlovschiNo ratings yet

- Introducción Gramatica InglesaDocument25 pagesIntroducción Gramatica InglesaJavi TarNo ratings yet

- Verbal Reasoning - SeriesDocument263 pagesVerbal Reasoning - SeriesAshitha M R Dilin0% (1)

- Matt. 7:1-5Document3 pagesMatt. 7:1-5Sid SudiacalNo ratings yet

- Martina Smith Soc 150 Davis Sociological Perspectives October 4, 2019Document8 pagesMartina Smith Soc 150 Davis Sociological Perspectives October 4, 2019M SmithNo ratings yet

- 10Document145 pages10keshavNo ratings yet

- 7 ProverbsDocument108 pages7 Proverbsru4angelNo ratings yet

- Leasing .NET Core - Xamarin Forms + Prism - Xamarin Classic + MVVM CrossDocument533 pagesLeasing .NET Core - Xamarin Forms + Prism - Xamarin Classic + MVVM CrossJoyner Daniel Garcia DuarteNo ratings yet

- Muestra Eyes Open 4 WBDocument7 pagesMuestra Eyes Open 4 WBclau aNo ratings yet

- Year 3 Unit 9 The HolidaysDocument8 pagesYear 3 Unit 9 The HolidaysmofardzNo ratings yet