Professional Documents

Culture Documents

What Defines a Neighbourhood? An Externality-Space Approach

Uploaded by

Veronica TapiaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

What Defines a Neighbourhood? An Externality-Space Approach

Uploaded by

Veronica TapiaCopyright:

Available Formats

What is neighbourhood?

An externality-space approach

by George C. Galster

1 Context

Ironically, while all those concerned with cities seem to understand the term

neighbourhood in its common usage, no one seems to be able to agree on exactly

what it means or how it should be spatially specified. Weseem to be conceptually

impaled on the horns of a dilemma. On the one hand, views of neighbourhood

grounded in individual cognition and collective sentiment and symbolism, though

perceptually meaningful, have had little operational content since they have not

been employed in the specification of precise, geographic neighbourhood boun-

daries. On the other hand, views of neighbourhood as defined by clear administra-

tive boundaries have had no necessary correspondence with the perceptual reality

of individuals in the given area.

Undoubtedly, there is a consensus that the neighbourhood is a social/spatial

unit of social organization . . . larger than a household and smaller than a city

(Hunter, 1979, 270). But here is where consensus ends. Academicians (especially

sociologists) have focused on questions of the social meaning of space: how far do

social interaction networks extend over space? What social support is drawn from

surrounding residents? What social symbolic significance does an area assume?

Numerous definitions can be found in the social science literature, varying in their emphases

and degree of ambiguity. A representative sampling follows:

Ecological: A place with physical and symbolic boundaries (Keller, 1968, 89). Place

and people, with the common sense limit as the area one can easily walk over (Morris

and Hess, 1975, 6). A physical or geographical entity with specific (subjective)

boundaries (Golab, 1982, 72). A distinct housing submarket (Ahlbrandt and Brophy,

1975.6).

Interactive: A social organization of a population residing in a geographically proximate

locale (Warren, 1981, 62).

Ecological interactive: A limited territory within a larger urban area, where people inhabit

dwellings and interact socially (Hallman, 1984, 13). Geographic units within which

certain social relationships exist (Downs, 1981, 15). Common named boundaries, more

than one institution identified with area, and more than one tie of shared public space or

social network (Schoenberg, 1979,69).

Perceptual: In the last analysis, each neighborhood is what the inhabitants think it is

(National Commission on Neighborhoods, 1979, 7).

244 What is neighbourhood? An externality-space approach

Unfortunately for the most part, equally important questions have to be begged:

do neighbourhoods as specified by unambiguous, consensual boundaries exist?3 If

so, what role does social meaning play in their establishment? Can they exist in the

absence of local social interaction? Lack of consideration of these issues is under-

standable, given that the emphasis on social meaning leads one exorably to the con-

clusion that in the last analysis, each neighborhood is what the inhabitants think it

is (National Commission on Neighborhoods, 1979,7).

An exception has been Suttles (1972, Chapter 3), who argued that the social

aspect and spatial aspect of neighbourhood are intrinsically interrelated, and that

particular social functions are associated with different spatial levels of neighbor-

hood4 As valuable as this insight is, shortcomings remain. First, it is unclear how

one moves from individual perceptions to collective representations of neighbour-

hood; i.e. at whatever spatial level, how do neighbourhood boundaries spawned by

one individuals perceptions coincide with those of other, proximate residents?

Does the aggregation of individual perceptions result in the establishment of

unanimously agreed upon boundaries which delinate a mutually exclusive and

exhaustive set of neighbourhoods over urban space? If not (as is likely): what

leads to variations in this degree of perceptual concidence? At what point does a

lack of perceptual coincidence render the existence of neighbourhood prob-

lematic? Second, there is no compelling a prion reason that a meaningful ecological

neighbourhood can only be defined in terms of social interaction, sentiment and

symbolism. Such dimensions indeed may prove to be sufficient for the unam-

biguous specification of neighbourhood boundaries, but not necessarily so. Third, a

spatial neighbourhood delineated solely by these social dimensions may be the

inappropriate scale when one is attempting to analyse investment or mobility

behaviours which lead to changes in the physical condition or demographic com-

position of a given area.6

Most planners and public officials (and residents?) are interested in exactly these

Exceptions are Firey (1945), Lynch (1960) and Hunter (1974).

3Wellman (1972) raises a similar challenge when he chastizes those who disregard the caveats of

researchers who studied unique urban villages and uncritically accepted the existence of

neighbourhood.

4Suttles built upon the seminal insights of J anowitz (1952) and Greer (1962). In his view, the

most elemental spatial unit was viewed as the block face, the area defined by where children

are allowed to play without supervision. The second level was labelled the defended neigh-

bourhood: the smallest area possessing a corporate identity as defined by mutual opposition to

another area. The third level, the community of limited liability, typically consisted of an

administrative district in which individuals social participation was selective and voluntary. The

highest geographic level of neighbourhood, the expanded community of limited liability, was

viewed as an entire sector of a city. Surveys conducted by Birch et al. (1979, Chapter 3) have

revealed that residents do, indeed, conceive of four distinct spatial levels of neighbourhood

which correspond closely to Suttless theoretical hierarchy.

See Keller (1968) and Hunter (1974) for evidence on the interresident variability of neigh-

bourhood boundary specification.

6For empirical analyses of the appropriate geographic scale of neighbourhood vis-d-vis such

behaviour, see Galster (forthcoming).

George C Galster 245

mobility and investment behaviours, of course. They care less about social meaning

than operational precision. Given their need to specify some precise definition of

neighbourhood for which objective data can be gathered and analysed, they have

resorted to establishing ad hoc geographic boundaries. The result has been a

precise spatial definition of neighbourhood - planning district, census tract, etc. -

but one which may have little or no perceptual or behavioural significance for

anyone besides the boundary maker^.^Yet, if ones goal is to explain why certain

changes occur in a particular area and to predict how that area is likely to respond

to, e.g. a policy which alters its physical, demographic or social dimensions, one

cannot blithely rely on neighbourhood defined by fiat.

2 Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to present a new conceptual definition of neighbour-

hoods that is realist,m i.e. is grounded in the perceptions of people who are living

and investing in them. Algorithms are developed whereby individual perceptions

can be aggregated and the differences in these perceptions can be quantified. It is

suggested how operational, geographic specifications of neighbourhood might be

made based on empirical investigations that follow from these definitions and

algorithms. The operational specifications, in turn, open up a host of new possi-

bilities for testing hypotheses of interest to theoreticians and policy makers alike.

In other words, an attempt will be made to link explicitly perceptual and spatial

dimensions in order to derive a concept of neighbourhood that is both quantifiable

and holds the promise of improving our understanding of behavioural response to

environmental changes.

The fundamental way in which this approach to defining neighbourhoods differs

from previous attempts is that it employs an inductive versus deductive approach.

That is, prior attempts to specify neighbourhood in a way that was perceptually

meaningful have foundered on their inability to deduce precise geographic neigh-

bourhood boundaries from the theoretical constructs. I believe such a deductive

approach is inherently fruitless. Rather, a meaningful theoretical conceptualization

of neighbourhood is herein viewed as laying the groundwork for empirical tests in

which the geographic boundaries of neighbourhoods themselves are viewed as

For a more detailed discussion of this dichotomy between the social versus geographic view of

neighbourhoods, see Keller (1968,126,133).

Taub el al . (1977) has also noted that the need to identify a particular neighbourhood associa-

tion as a contact agent for the administration of social programmes can lead to the artificial

creation of neighbourhoods.

90ne possible exception is the Census Bureaus Statistical Neighbourhood Program which,

according to personal correspondence with a planning professor at the University of Cincinnati,

has been successful in specifying precise yet meaningful boundaries for Cincinnati neighbour-

hoods. For a description of a similar effort in Pittsburgh, see Ahlbrandt, Charney and Cunning-

ham (1977).

DFor more on the distinction between realist and nominalist approaches to boundary

definition, see Laumann, Marsden and Prensky (1983,20-22).

246 What is neighbourhood? An externality-space approach

dependent variables. In this way, the question of the existence of such boundaries

is not begged, but rather becomes the subject of hypotheses which may be tested

inductively. And here is where previous conceptual views about neighbourhoods

come into play; for it is precisely such characteristics as local social interaction,

culture, sentiment and symbolism which potentially can affect individuals percep-

tions in an area so as to produce varying degrees of coincidence among their

ecological views of neighbourhood.

It must be noted at the outset that this paper is conceptual and not empirical.

Its purpose is to explicate new concepts of defining and measuring neigh-

bourhood and to demonstrate thier potential usefulness in investigating a wide

variety of issues. Specific suggestions are provided, however, for operational-

izing the theory. It is beyond the scope of the present paper to conduct such

investigations.

I Neighbourhood as externality space

1 Overview

The fundamental claim of this paper is that neighbourhood can be meaning-

fully and usefully specified in terms of extemoliq space. Externality space is de-

fined as the area over which environmental changes initiated by others are per-

ceived as altering the wellbeing (psychological or financial) a given individual

derives from the given location. Three characteristics of these externality spaces are:

a) congruence - the degree to which an individuals externality space corresponds

to predefined geographic boundaries;

b) generality - the degree to which an individuals externality spaces for different

types of externalities correspond;

c) accordance - the degree to which externality spaces for different individuals

in the same area correspond.

Neighbourhood is not viewed in this paper as a unidimensional, dichotomous

entity, but rather as a variable whose magnitude can be measured along interval

scales in each of these three dimensions. In other words, for any specific dimen-

sion of neighbourhood one does not consider here whether it exists or does not

exist, but rather the degree to which it exists over a given space.u

How the concept of neighbourhood is built upon the notion of an indi-

viduals externality space and how the three dimensions of neighbourhood may

be specified from this foundation are explained in detail in the next three sub-

sections.

This view of neighbourhood owes an intellectual debt to the seminal suggestions of two scholars.

Segal (1979, 6) claimed that neighbourhoods might be specified in terms of externalities, and

Warren (1972, Chapter 1) noted that a vital dimension of a community is the extent to which

service areas of local units coincide.

George C. Galster 247

2 The individual perspective

From the perspective of a particular individual, say a resident or owner of property

at a given urban location, the externality space is defined as the area over which

changes in the environment initiated by others are perceived as altering the degree

of wellbeing (psychological and/or financial) the individual derives from the given

location. Note first that this definition considers the space over which particular

changes are both perceivedand are adjudged non-trivial. In other words, it is the space

over which stimuli indicative of changes in the quality of the individuals residential

milieu provide the necessary (though not sufficient) conditions for behavioural

response: outmigration, alteration in home maintenance, dwelling sale, revisions in

amount, type or locus of social interaction, etc. Changes are herein specified as

resulting from the actions of others which are external to the given individual, i.e.

are not the result of direct market or social transactions between the individual and

the other person(s).n The focus is on changes which are exogenous to the indivi-

dual because the ultimate proposed use of this definition is as a tool for analyzing

and predicting individual behavioral responses to such.u All sorts of externalities

could be considered in principle. Examples would be: the construction of a public

playground on a vacant lot on the block, a person of a different race moves into the

house next door, several close friends die or move out of the neighbourhood.

The geographic boundaries of this individuals externality space cannot be more

precisely specified until one knows more about the externality(ies) under considera-

tion, the individuals beliefs and attitudes, the local social networks between the

individual and proximate others, and the spatial pattern of the individuals habitual

travels. In other words, the externality space is a function of how individuals

evaluate the particular externality, how their peers evaluate it, and whether they are

aware of its existence, either first-hand through direct observation or second-hand

through interpersonal communication.

Consider, initially, the externality of litter as an illustrative example. An indi-

vidual may not readily perceive or be concerned about the presence of litter on an

adjacent block, but more likely would if it were on the individuals own block. In

such a case the individuals externality space for litter would consist of the block-

face. Analogously, the externality space over which the individual is sensitive to the

immigration of households of lower socioeconomic status is probably more

expansive. Still larger may be the externality space for such externalities as new

nNote this usage is somewhat more general than the way in which the term externality is

conventionally employed in economics; see Schreiber and Clemmer (1982).

? h e approach of speafying neighbourhood in the context of individual behavioral responses

to external stimuli is consistent with the theory propounded by Franz (1982). He asserts that it

is only in these reactions to these disturbances that the boundaries of neighbourhoods become

empirically visible.

It has been suggested that individuals ability to produce clear mental maps of urban space

is enhanced by their frequency of travel through the area; see Lynch (1960), Jacobs (1961),

Mlligram el al . (1972).

248 What is neighbourhood? An externality-space approach

shopping centres or public facilities.5

Of course, exactly when some externality comes close enough to be perceived

and to be assessed as influencing ones residential wellbeing depends on the char-

acteristics of the observer. Elderly households and households with children may

be, for example, relatively more sensitive to the approach of hgher crime.

Similarly, white bigots would have a larger externality space vish-vis new black

residents than would more tolerant whites.

In the case of households and owner occupants, the externality space may also

be influenced by the social character of the surrounding area. Although the social

dimension of space may, itself, be the source of an externality, it also can influence

the likelihood of individuals in that space perceiving a given physical, demographic,

or social interactive externality and the way in which they evaluate its conse-

quences. For instance, if a person is embedded within a spatially-dense social

network (e.g. a traditional ethnic enclave), that person will be exposed to much

second-hand information about and interpretation of spatial events which otherwise

might not have been perceived through first-hand observation. The individuals

evaluation of perceived information may also depend on the acculturation which

has occurred in the local social milieu. As illustration, one who has resided for a

long time amid professional-status residents might grow more favourably-disposed

toward valuing everything in its place, i.e. rigid separation of land uses. This

individual might therefore specify a more spatially-extensive perceptual boundary

for non-residential land uses compared to a person inculcated with the values of

proximate working-class residents. These latter considerations may be included

under the rubric symbolic communities (Hunter, 1974).

Given an individual ( n) with particular characteristics who is embedded in a

particular spatial-social environment, two dimensions of his/her externality space(s)

can be specified. The first, individual congruence (C,,), is the degree to which

individual ns perceptual boundaries of the externality space (Yen) for a particular

externality ( e) correspond to some predetermined geographic boundaries defined

by streets, topographical features, or administrative fiat that delineate a space (X)

containing the property which the nth individual invests or resides in.& Formally,

the congruence between this individuals particular externality space and the given

area is specified as:

'Sit should not be inferred from the above that externality spaces necessarily have regular

shapes. The algorithms presented below make no assumptions in this regard. None of the

measures are unique, however; an infinite number of topological configurations could produce

the same value for C, G or A.

mNote that the definition of congruence used here is very different than that employed by

Michelson (1976, 26), which refers to states of variables in one system coexisting better with

states of variables in another system than with other alternative states.

Georpe C Galster 249

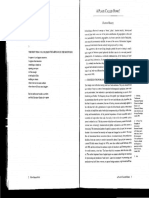

where n and U signify intersection and union, respectively, in set terminology.

Heuristically, X n Ye, represents the area of the region where person ns perceptual

map for the impact of externality e overlaps the map of the specified area; X U Y ,

represents the sum of the areas of X and Y. Visually, this measure is portrayed in

Figure 1 c. C,, ranges from a minimum of zero to a maximum of one.

The second dimension, generality, is the degree to which individual ns exter-

nality spaces (Y) correspond across E number of different externalities. Formally,

individual ns generality is:

Heuristically, GE, represents the summed ratios of overlapping to total areas of

externality spaces specified for a variety of potential externalities, for all possible

permutations of externality combinations excluding identities (e=fl . C, , ranges

from a minimum Of Zero to a maXimUm Of 2 e . Visually. This measure is par-

E- 1

z

e- 1

trayed in Figure 1 b.

3 The aggregate perspective

It is at the point where individual perceptions of neighbourhood are aggregated

over a given spatial grouping of individuals that the operational geographic meaning

of neighbourhood has been typically rendered ambiguous in previous studies. I

would suggest that this can be avoided by focusing on the question: to what degree

does neighbourhood exist in a given place? The following discusses how this focus

provides the basis for simultaneously defining and measuring neighbourhood at

the group level. The analysis revolves around aggregate measures of the two dimen-

sions introduced above - congruence and generality - and adds a third -

accordance.

As above, begin by taking as given some predetermined geographic area of a city

with clearly-specified cartographic boundaries: area X. This spatial set will demar-

cate a particular number ( I ) of residents who live in X, ( J ) owners of property in

X , and ( K ) others with financial interests in the property in X , such as real estate

brokers or financial institution officers. From this group all or some subset may be

selected as the basis for analysis. Let this group consist of N members.

Now the aggregate degree of congruence for the space X for given externality

e over N members of the given group is the summation of individual congruence as

defined in (1):

250 What is neighbourhood? An externality-space approach

0 ........

--1

I mm.0

I ---

I -

I-

I

I

0

0 ........

Key to hypothetical situation

Boundary for Person A, externality 1

Boundary for Person A, externality 2

Boundary for Person 8, externality 1

'Official' boundary

1 a 'Accordance'

For persons A, B; externality 1

Aggregate

Accordance =ratio of %area to total area

covered by combined boundaries

0

0

0

.........

George C Galster 251

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

1 b 'Generality'

For person A; externalities 1 and 2:

Individual

Generality =ratio of //,area to total area

covered by combined boundaries

Aggregate

Generality =sum of individual generalities

for persons A and B, externalities 1 and 2

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0

0

0

0

0

0

l c 'Congruence' 0

For person A vs 'official' area; externality 1 :

Individual

Congruence =ratio of ;/area to total area

covered by combined boundaries

Aggregate 0

Congruence =sum of individual

congruences for persons A and B,

externality 1 0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 * 0

Figure 1

fied example

Graphic illustrations of three dimensions of neighbourhood for simpli-

252 What is neighbourhood? An externality-space approach

where N =Z, J, K or combinations or subsets thereof. Thus, aggregate congruence

for a particular externality is specified in terms of a group sum of the ratios of

overlapping to total areas of X versus the members externality spaces. Maximum

aggregate congruence is obtained (Cm =N)when each group members perceptual

space for the given externality corresponds to the specified area; minimum con-

gruence is obtained (CeN =0) whea there is no correspondence whatever.

As will be indicated in a later section, it sometimes might be desirable to define the

aggregate congruence of an area only in terms of a subset of individuals and a single

e~ternal i ty. ~ If, however, one wishes to define a more aggregated level of con-

gruence, (3) can be easily expanded to include summations across all individuals in

area X and all E externality types:

where 0 C,, < E. Nand N =I + J + K

Next we can consider the second dimension of the aggregate neighbourhood -

generality - the aggregate degree to which the individuals externality spaces

coincide for E different externalities, as given by ( 2 ) summed over N individuals:

N E E

N =I, if residents; J , if owners; K , if others; or combinations of Z, J, K . Aggregate

generality is thus the total of the ratio of overlapping to total areas of all possible

externality space comparisons, summed over all group members in area X. The

generality of area X over a variety of E different externalities would be maximized

(GEN =2N ye) for a given group in X if each individual in the group perceived

the same boundaries for all externalities (although these boundaries need not

coincide fiom individual fo individua2). Generality would be minimized (GEN =0)

if each and every individuals externality space for any given externality did not

overlap with that for any other externality.

The final aggregate dimension is accordance: the degree to which all N indivi-

duals externality spaces for a given externality e overlap. It may be specified as:

c = 1

N may consist of a subset of residents, owners or brokers based on race, income, age, etc.

George C Galster 253

N - 1

where N = I, J, K or combinations thereof; 0 Q A , < 2 7 n. Accordance for a

L

n-1

given externality is thus the total of the ratios of overlapping to total areas of all

possible interpersonal comparisons of e externality space for N groups members in

area X . This is visually portrayed in Figure l a.

Accordance over all externalities is found by summingAeN over E:

N-1

Such accordance for area X would be maximized (AEN =2E n) if each member

L

n-1

in the group perceived the identical externality space for a given externality, and

this was true for every externality (although the spaces across externaZities need not

be identical). Accordance would be minimized (AEN =0) if no two individuals

externality spaces overlapped for a given externality, and this was true for all

externalities.

It should be noted at this point that CEN, C,, A , as specified are interval

measures of three distinct dimensions of the aggregate relationships between exter-

nality spaces existing for some predefined area. As such they are not comparable

in a cardinal sense. Certain logical connections do exist between them, of course.

For instance, AEN and G,, maximization is a necessary (but not sufficient) condi-

tion for C,, to be maximized. In other words, for everyone in an area to agree

that its predetermined boundaries accurately reflect their externality space for all

externalities, they must also agree that their externality space is the same across all

people and all externalities. The converse is not true, however; there may be

complete accordance and generality, but the common space thus specified may

have little congruence with the predetermined area. Through analogous logic it may

be demonstrated that A and G minimization is neither a necessary nor a sufficient

condition for CE, minimization. Finally, A , and C , serve as constraints on

the maximum CEN level attainable for a given spatial set X . Although no precise

mathematical relationship can be given at this level of generality, it is intuitively

clear that if, e.g. A,, and G, are low, CE, will tend to be also. That is, if there

is little overlap of externality spaces across various individuals and across various

externalities, there cant be much consistent overlap between these spaces and the

given area X .

4

At this point we can now discuss what neighbourhood means. Neighbourhood is

both defined and measured by its congruence, generality and accordance. Each

Congruence, generality, accordance and neighbourhood

254 What is neighbourhood? An externality-space approach

dimension may only be specified in terms of particular perceptual group(s) and

externality(ies) being perceived. Once having specified such a context, the neigh-

borhood associated with a given place or group of individuals can be considered in

terms of the degree to which it manifests congruence, generality, and accordance.

For a predetermined spatial set of individuals, should there be an area over which

accordance and generality (for particular exteralities) were high, it would imply

not only that a neighbourhood exists but its boundaries would be defined. If

accordance and generality were low we would conclude that no meaningful spatial

neighbourhood existed for this group. For a predetermined area (and the indivi-

duals implicitly contained therein), the degree to which neighborhood is mani-

fested there would be primarily measured by congruence, although as noted above

the degree of congruence possible can be influenced by accordance and generality.

If congruence were low we would conclude that the given boundaries did not pro-

vide good proxies for the neighbourhood (potentially) perceived by these indi-

viduals.

I1

The preceding theoretical analysis implies that the way to convert the concept of

neighbourhood into an operational measure useful for empirical research and

planning purposes is to specify boundaries in terms of how, in aggregate, people

map their externality spaces. If one is attempting to designate meaningful neigh-

bourhoods a priori, the goal would be to specify an area X such that a predeter-

mined form of congruence is maximized. Although it is beyond the scope of this

paper to undertake such an empirical investigation, an outline of a suggested pro-

cedure will be presented.

Depending on the ultimate analytical reason for the investigation, the research

would first need to choose one particular externality or subset of them, as well as

one or more particular groups of people to focus on; i.e. the particular dimensions

over which neighbourhood will be assessed must be specified. For example, one

might only want to explore behavioural responses of a certain type of household to

the proximate inmigration of persons of lower socioeconomic status. Or, at the

other extreme, for planning purposes one might be interested in the parameters of

a more general neighbourhood for a broad set of externalities that might be regu-

lated by zoning, as perceived by residents, owners, real estate brokers, and officers

of financial institutions alike.

Second, the research would need to ascertain how each individual in the chosen

sample perceived his or her externality space(s). At least two methods for doing this

come to mind. The first would involve the administration of carefully designed

opinion polls to reveal the distance at which respondents begin to perceive that

certain generators of externalities affect them. In this vein one could either query

about alternative hypothetical situations and likely perceptions or ascertain actual

perceptions of particular externalities and, after noting the specific locations of

Making the neighbourhood concept operational

George C. Galster 255

respondent and externality(ies), infer a perception-distance relationship. A

technique analogous to the former has already been extensively used to investigate

how whites would evaluate alternative proximities of black neighbours (Pettigrew,

1973; Farley et al., 1978). The potential weakness of this approach is that evalua-

tions of hypothetical externalities may not correspond to evaluations of real ones if

such are not cognitively perceived in a particular instance. The latter approach

above is superior in this regard since perceptions and evaluations of existent extern-

alities are being recorded. Some investigations along this line have been conducted

by Scotland and Galster (1977), which deal with externalities associated with deter-

iorated housing.s Of course, the shortcoming of this latter approach is that the

range of analysis is restricted to the set of externalities currently perceived (in

varying degrees) by the given sample.

The second method would be based on indirectly eliciting information about

individuals externality spaces which is implicit in their perceptions of property

values. More specifically, data could be gathered about the characteristics of indivi-

duals homes, their surrounding environment, and what they currently perceive

their property to be worth. A multiple regression of this self-assessed property value

on all these characteristics would yield estimates (in the form of regression coef-

ficients) of the relative contributions made by each characteristic. If variables were

carefully specified as proxies for the existence of a variety of externalities at various

distances from the given observation, the magnitude and statistical significance of

their coefficients would provide the desired information about the point at which

externalities begin to impinge. Several studies have employed this hedonic index

methodology to assess the spatial extent of externalities generated by, e.g. non-

residential and multifamily land uses (Grether and Mieszkowski, 1980), racial com-

position (Galster, 1982), and human service facilities (Gabriel and Wolch, 1984).

The conceptual difficulty with this approach are the assumptions that: a) all

relevant social, physical and demographic externalities are capitalized into property

values and b) self-assessed housing value is more a reflection of the respondents

own perceptions and preferences, and not their view on what the rest of the market

believes. The operational difficulty is the requirement of an extremely rich and

large household data base for local areas.

Whichever of the above techniques is used in the second step, the end product

must be a mapping of each particular externality space for each sampled individual.

The third step would be to specify geographic neighbourhood boundaries over the

given space which maximize the congruence between themselves and the extern-

ality spaces obtained from the sampled individuals in the second step. Undoubt-

edly, the only feasible way to accomplish this for large samples would be by

computer iteration/simulation. Such a computer program might well begin with the

criteria for selecting a spatial grouping out of a large number of alternatives as

proposed by Cliff et al. (1975). Such a simulation could employ, if desired, various

A multivariate linear probability equation indicated that people noted that the deteriorated

housing became bothersome only when it was located on their blockface.

256 What is neighbourhood? An externality-space approach

constraints on, e.g. a maximum number of neighbourhoods defined over the space

or a minimum area per neighbourhood. In addition, the simulation program could

calculate generality and accordance values for each of the neighbourhoods resulting

from the congruence-maximizing algorithm.

The preceding three-step methodology would reveal to the researcher what the

neighbourhoods for the given externality(ies) and group(s) geographically looked

like in the particular area. In addition, tests conducted with the congruence-

maximizing algorithm could reveal how sensitive congruence was to slight alter-

ations of boundaries or in the number of neighbourhoods specified. For instance,

one might be particularly interested in how much congruence is lost when one

adopts some previously established administrative or traditional boundaries instead

of the best ones.The accordance and generality values calculated for the neigh-

bourhoods generated in the simulation would also tell the investigator the degree

to which these neighbourhoods exist in similar ways across individuals in the

sample and across externalities. In other words, the boundary of maximum con-

gruence need not imply that congruence is high absolutely; accordance and gener-

ality may still be relatively low. Thus, whether neighbourhood is meaningful for

all or some of the locales in a given analysis can be assessed from the method-

ology.

As a final point, consider the contrasts between the suggested methodology and

that conventionally used: asking residents to draw or name the boundaries of

their neighbourhood; e.g. see Hunter (1974). Certainly, the latter technique is

operationally simpler. Once obtained, such maps could be subjected to accordance

and congruence calculations according to equations 6 and 3, respectively. And

this, indeed, would be an interesting exercise. It would not, however, produce very

precise measurements because there would remain residual ambiguity concerning

what type or level or neighbourhood (re: externality space) respondents were

implicitly considering when making their maps.

I11 Discussion

1

How does the foregoing analysis correspond to the conventional sociological

notion of neighbourhood as arena for social interaction and symbolic com-

munity? (Hunter, 1974; 1979). Quite simply, the social dimension is herein viewed

as a prime factor delineating an individuals externality space. Borders specified

by tradition and sentiment can serve as diodes for the perception of externality:

within the border all externalities are important; without they are not. The degree

to which group members become aware of the existence of externalities within

the border depends on the areal information nexus: how quickly and compre-

hensively news is transmitted over space by interpersonal communication. Finally,

whether recognized externalities within the border are seen as threats, windfalls,

The social dimension of neighbourhood

George C Galster 257

or inconsequential is influenced by the socialization which has transpired in the

area.

The algorithms outlined in this paper provide for the first time a framework for

testing quantitatively these various roles of the social neighbourhood. Numerous

potential research questions come to mind. What is the relationship between the

spatial density of social networks and the areas accordance and generality? If, as

Hunter (1 974) has suggested, neighbourhood perceptions vary between categories

of individuals, which specific groups (age, sex, race, SES, etc.) manifest the least

degree of accordance? Does a given intergroup dearth of accordance persist over

various types of externality spaces?

2

Lynch (1960), J acobs (1961) and Milgram et al. (1972) have shown how people

mentally map their urban surroundings and how the visual character of the

physical environment influences the clarity of these maps. Hunter (1974, Chapter

2) has found that 80% of Chicago residents descriptions of neighbourhood boun-

daries involved streets. Of these streets, 63% were within one block of vacant land,

55% were within one block of a railroad. In the context of the present model, these

findings can be interpreted in two ways. First, distinctive physical features can serve

as a rough-and-ready referent for judging the proximity of externalities, much as

social symbolism functions. Second, certain types of externalities may, in fact, be

physically impeded by certain physical barriers.

Perhaps of more interest is the potential for testing empirically these proposi-

tions. For example, do areas of high Lynchian imageability possess larger degrees

of accordance and generality? Can the creation or modification of edges, paths,

landmarks and nodes (see Lynch, 1960) dramatically augment these measures

and, indeed, create neighbourhood?

The visual-physical dimension of neighbourhood

3

The notion of generality relates to Suttless (1972) and Birch etal.s (1979) afore-

mentioned observations that people are cognitive of four distinct spatial levels of

neighborhood. I would posit that these results stem from individuals categoriza-

tion of various potential physical, demographic and social-interactive changes into a

hierarchy of externality spaces. At each level the appropriate subset of external-

ities would indicate high generality. The veracity of this interpretation awaits

further empirical tests, of course. What are the groups of externalities which cluster

with high degrees of generality at different spatial levels?

Four spatial levels of neighbourhood

sSee Wellman (1979) and Wellman and Leighton (1979).

258 What is neighbourhood? An externality-space approach

4 An array of neighbourhoods

The foregoing analysis suggests that neighbourhood is a concept which varies in

three distinct dimensions. Actual urban spaces thus may be arrayed within a matrix

according to their scores on these dimensions, analogous to a social area analysis.

Such an array provides the means for integrating disparate concepts of neighbour-

hood appearing in the literature. Cases where we get high accordance, generality,

and congruence in an area (e.g. clustered people with similar ethnic and socioecon-

omic backgrounds, little intergenerational mobility, dense spatial social networks,

high imageability of the physical environment) have been called the urban

villages (Cans, 1962). At the other extreme, areas characterized by low scores on

these three measures (e.g. people of diverse backgrounds, beliefs and preferences,

who move frequently, have spatially-dispersed networks, and inhabit a visually-

indifferentiated space) have provided testimony for the death of neighbourhoods

(Hunter, 1975; Wellman, 1972; 1979; Wellman and Leighton, 1979). Places having

values of accordance, generality and congruence between these two poles might

be referred to as generic neighourhoods.

Note that this represents a typology which is distinct from those which have

been used conventionally; for a review see Hunter (1979). The quantitative estima-

tion of the frequency of neighbourhoods at different points in the array and the

intertemporal and cross-sectional variations in these distributions provides a fertile

area of future research. Whats more, the meaning and significance of different

degrees of these indices deserves investigation. What kind of social, economic and

political reality is hidden behind a certain constellation of congruence, generality

and accordance? Such a question leads inexorably to the next area of discussion.

5 Bediction and policy evaluation

The model presented in this paper provides implications for. researchers and

planners who want to be able to predict and, if necessary, alter spatial change.

Alterations in the physical, demographic and social-interactive character of a given

area result from changes in the flows of households and resources into that area.

These flows are produced, in turn, by the individual mobility and investment deci-

sions of the residents, property owners, real estate agents, and financial institutions

who have interests in that space (Downs, 1981, Chapter 1). Changes in mobility and

investment behaviour are triggered by proximate events which produce external-

ities and thereby alter the wellbeing derived from the given residential environment.

Such behavioural responses can, of course, only ensue after ones externality space

has been penetrated.

Hence, understanding the degree to which neighbourhood exists over a given

space is a prerequisite for comprehending and predicting changes in that space. For

ZOFor contrasting schema for providing neighbourhood typologies see, e.g. Schoenberg and

Rosenbaum (1980) and Warren (1981).

George C. Galster 259

example, if the racial composition of residents on a certain block changes, how

many residents on adjacent blocks will perceive this as a change in their neighbour-

hood? If there is a wide disparity among residents on these adjacent blocks as to

their cognizance of the change, their sense that it is in their neighbourhood, and

whether it affects their wellbeing, there would be less likelihood of the spasmodic

tipping of the area. Thus, the accordance of an area becomes important for pre-

dicting responses to a particular externality generator. Similarity in the pattern of

such responses across different externality types will depend on the generality of

the area.

The measurement of neighbourhood in an area is also crucial for assessing the

impact of various public policies designed to alter the physical or demographic

dimensions of the local urban environment. Suppose, for instance, planners were

considering renovating a certain blockface or putting in a new park. Relevant ques-

tion would then be: who will view such a change as an alteration in their neighbour-

hood? Over what area are these people spread? How large a portion of all residents

in this area do they represent? In terms of the present model, such policy decisions

should be guided initially by an examination of the neighbourhood mapping pro-

duced by the maximizing-congruence algorithm (described above) as applied to the

particular externality generator being contemplated in the policy (renovation, park,

etc.) It is noteworthy that these boundaries may differ considerably from those

typically employed by planners, given the implications of several case srudies.n

Having established such, the planners could then measure accordance within these

areas in order to proxy for one measure of the efficacy of the policy.

A final way in which the above concepts may be relevant to contemporary pro-

grammatic concerns relates to the issue of local community political power. It has

been claimed that a central problem in microcommunity control of the environ-

ment is the absence of any authoritative way in which residents can appeal to a

single set of boundaries (Social Science Panel, 1974, 77). If, for this political

reason, one wanted to build neighbourhood(s), the existing levels of accordance

and generality within congruence-maximizing boundaries would provide an

indicator or where such community organizing efforts might be most propitious.

Furthermore, the success of such efforts to mobilize collective sentiment and

common symbolism could be measured by estimating increases in accordance and

generality over time.

6

As a closing comment, it should be noted that the approach proposed in ths paper

may have broader applicability than merely for the analysis of the urban neighbour-

Broader applicability of the approach

a

For a variety of studies indicating that residents perceptual boundaries differ from those

defined administratively, see Ahlbrandt, Charney and Cunningham (1977, 338), Schoenberg

and Rosenbaum (1980, Chapter 7). Warren (1981, 88), Hallman (1984, 57-59), Vaskowics

and Franz (1984. 152).

260 What is neighbourhood? An externality-space approach

hood. Indeed, the constructs of accordance, generality and congruence could be

applied to any number of networks having a geographic content that is potentially

bounded. For instance, the constructs could be applied to a given set of individuals

so as quantitatively to contrast their social ties of differing levels of frequency of

intimacy, or their various types of resources obtained from alternative institutions;

see Berkowitz (1982). Whether such applications can indeed provide an important

contribution to structural analysis must await further research.

Acknowledgements

I wish to gratefully acknowledge the provocative comments and questions tendered

by Peter Franz, J ohn Macionis, David Varady, Patricia Wittberg and anonymous

referees on an earlier draft of this paper.

IV References

Ahlbrandt, R. and Brophy, P. 1975 : Neighborhood revitalization. Lexington:

D.C. Heath.

Ahlbrandt, R., Chamey, M. and Cunningham, J. 1977: Citizen perceptions of their

neighborhoods. Journal of Housing 7,338-41.

Ahlbrandt, R. and Cunningham, J . 1979: A new public policy for neighborhood

preservation. New York: Praeger.

Berkowitz, S.D. 1982: An introduction t o structural analysis. Toronto: Butter-

worth.

Birch, D. Brown, E., Coleman, R., Da Lomba, D., Parsons, W., Sharpe, L. and

Weber, S . 1979: The behavioral foundations of neighborhood change. Wash-

ington: USGPO/HUD.

Clay, P. 1979: Neighborhood renewal. Lexington: D.C. Heath.

Cliff, A., Hagget, P., Ord, J.K., Basset, K. and Daries, R. 1975: Elements of spatial

Downs, A. 198 1 : Neighborhoods and urban development. Washington: Brookings.

Farley, R. Schuman, H., Bianchi, S., Colastano, D. and Hatchett, S. 1978: Choco-

late City, Vanilla Suburbs: will the trend toward racially separate communities

continue? Social Science Research 7, 319-44.

Firey, W. 1945: Sentiment and symbolism as ecological variables. American Socio-

logical Review 10, 140-48.

Franz, P. 1982: Zur Analyse der Beziehung von Sozialokologischen Prozessen und

Socialen Problemen. In Vaskovics, L., editor, Zur Raumbezogenheit Socialer

Probleme, Opladen, Germany.

Gabriel, S. and Wolch, J . 1984: Spillover effects of human service facilities in a

racially segmented housing market. Journal of Urban Economics 16, 339-50.

Galster, G. 1982: Black and white preferences for neighborhood racial composition.

American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association Journal 10, 39-66.

forthcoming: Neighborhoods, homeowners, and housing upkeep. Wooster, Ohio,

monograph in press.

structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

George C Galster 261

Cans, H. 1962: The urban villagers. New York: Free Press.

Goetze, R. 1979 : Understanding neighborhood change. Cambridge: Ballinger.

Golab, C. 1982: The geography of neighborhood. In Bayor, R., editor, Neighbor-

Greer, S . 1962: The emerging city. New York: Free Press.

Grether, P. and Mieszkowski, P. 1980: The effects of nonresidential land use on the

prices of adjacent housing: some estimates of proximity effects. Journal of

Urban Economics 8, 1-15.

Hallman, H. 1984: Neighborhoods: their place in urban life. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Hunter, A. 1979: The urban neighborhood: its analytical and social contexts.

hoods in urban America. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat.

Urban Affairs Quarterly 15, 267-88.

1974: Symbolic communities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

1975: The loss of community. American Sociological Review 40, 537-52.

J acobs, J . 1961: The death and life of great American cities. New York: Random

J anowitz, M. 1952: The community press in an urban setting. New York: Free

Keller, S . 1968: The urban neighborhood. New York: Random House.

Laumann, E. Marsden, P. and Prensky, D. 1983: The boundary definition problem

in network analysis. In Burt, R. and Minor, M., editors, AppZied network

analysis, Beverly Hills: Sage.

House.

Press.

Lunch, K. 1960: The image of the city. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Michelson, W. 1976: Man and his urban environment. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Milgram, S., Greenwald, J ., Kessler, S., McKenna, W. and Waters, J . 1972: A

Morris, D. and Hess, K. 1975: Neighborhood power. Boston: Beacon Press.

National Commission on Neighborhoods 1979: People, building neighborhoods.

Washington: USGPO.

Pettigrew, T. 1973: Attitudes on race and housing. In Hawley, A. and Rock, V.,

editors, Segregation in residential areas, Washington: National Academy of

Sciences.

Schoenberg, S. 1979: Criteria for the evaluation of neighborhood viability in

working class and low income areas in core cities. Social Problems 27,69- 85.

Schoenberg, S. and Rosenbaum, P. 1980: Neighborhoods that work. New Bruns-

wick, NJ : Rutgers University Press.

Schreiber, A. and Clemmer, R. 1982: Economics of urban problems, third edition.

Boston: Houghton-Mifflin.

Scotland, J . and Galster, G. 1977: Federal rehabilitation programs: are they worth

it? Urban Studies Working Paper, The College of Wooster, Wooster.

Sepal, D. 1979: The economics of neighborhood. New York: Academic Press.

Social Science Panel 1974: Toward an understanding of metropolitan America.

San Francisco: Canfield Press/National Academy of Sciences.

Suttles, G. 1972: The social construction of communities. Chicago: University of

Chicago Press.

Taub, R. Surgeon, G., Lindholm, S., Otti, P.B. and Bridges, A. 1977: Urban volun-

tary associations, locally based and externally induced. American Journal of

Sociology 83,425-42.

psychological map of New York City. American Scientist 60, 194-200.

262 What is neighbourhood? An externality-space approach

Vmkowics, L. and Franz, P. 1984: Residential areal bonds in the cities of West

Germany. In Peachey, P., Bodzenta, E. and Mirowski, W., edi tors, The residen-

tial areal bond, New Y ork: I rvington.

Warren, D. 1981: Helping networks. Notre Dame, I ndi ana: Notre Dame University

Press.

Warren, R. 1972: The community in America, second edition. Chicago: Rand-

M cNally .

Wellman, B. 1972: Who needs neighborhoods? In Powell, A., edi tor, The city:

attacking modern myths, Torono: McClelland and Stewart.

1979: The community question. American Journal of Sociology, 84, 1201-31.

Wellman, B. and Leighton, B. 1979: Networks, nei ghborhoods and communities.

Urban Affairs Quarterly 14, 363-90.

Cet article presente tout dabord une definition conceptuelle de Iunitt de voisinage, definition

approprite ti Iexamen et la prevision des rtponses comportementales des individus face aux

changements de leur environnement immediat. La notion de voisinage est perque par les

personnes qui vivent et/ou investissent dans un espace habitable donne. Le voisinage est defini

en termes despace dexternalitt, cest-a-dire Iespace dans lequel tout changement

environnement cause par un tiers est pequ comme une attente au bien-ttre dont un individudonne

jouit dans Iespace considere. Ensuite, des algorithmes sont tlabores lesquels les perceptions

individuelles peuvent etre curnulees et leur differences quantifiees selon trois dimensions scalaires:

leur congruence, her generalite et leur concordance. Ces trois echelons expriment le degre de

consensus sur les limites des espaces dexternalite: I ) par comparaison a des limites pre-

determintes ou officielles, 2) entre individus dans un espace donne 3) entre differents types

despaces. Ensemble, ils traduisent la mesurabilite de la notion de voisinage pour un espace

donne. Cet article avance quil est possible detablir des specifications operationnelles et

gtographiques du voisinage a partir dinvestigations empiriques dkcoulant de ces algorithmes.

Enfin. a la lumitre de cette thtorie, les conceptions traditionnelles du voisinage et leurs

implications politiques sont discuttes sous un nouveau jour et de multiples axes de recherche

empirique sont proposes.

Z u Beginn der Abhandlung wird eine Definition des Begriffs Nachbarschaft gegeben, anhand

derer die Verhaltensweisen des einzelnen als Reaktion auf Veranderungen in seiner sozialen

Umgebung untersucht und vorausbestimmt werden konnen. Ausgangspunkt sind die

Wahrnehmungen der Menschen, die in einem gegebenen Bezirk leben und/oder darin eine aktive

Rolle Spielen. Nachbarschaft wird definiert als aukrlicher Wahrnehmungsraum, d.h. der

Bereich, in dem der einzelne durch andere bewirkte Umgebungsveranderungen als eine

Veranderung seines Wohls wahrnimmt, das er in einem gegebe nen Bezirk genieBt. Als nachstes

werden Verfahren entwickelt, mit deren Hilfe einzelne Wahrnehmungen aggregiert und die

Unterschiede innerhalb dieser Wahrnehmungsfolge mittels dreier skalarer GroBen quantifiziert

werden konnen: Kongruenz, Allgerneingiiltigkeit, Ubereinstimmung. Diese drei GroOrn

geben an, in welchem MaBe Grenzen von auBerlichen Wahrnehmungsraumen miteinander

ubereinstimmen, 1) wenn sie mit einer vorher bestimmten oder offiziellen Grenze verglichen

werden, 2) ganz allgemein bei beliebigen Individuen fur einen gegebenen auBeren

Wahmehmungsraum, 3) ganz allgemein bei verschiedenen Arten von auOeren

Wahrnehmungsraumen. Alle drei GroBen zusammen dienen als quantitativer Indikator fiir das

AusmaO, bis zu dem eine bedeutungsvolle Nachbarschaft innerhalb bestimmter Grenzen

definierbar ist. Weiterhin werden Vorschlage gemacht, wie operationale, georgraphische

Spezifikationen fur den Begriff Nachbarschaft auf der Basis empirischer Untersuchungen

gefunden werden konnen, die sich aus den genannten Verfahren ergeben. AbschlieBend werden

neue Einsichten in traditionalle Vorstellungen von Nachbarschaft und die Bedeutung fur

Untersuchungsmethoden vor dem Hintergrund der Theorie diskutiert. Dariiber hinaus werden

zahlreiche Leitlinien fur die empirische Forschung gegeben.

George C Galster 263

Primeramente, la ponencia presenta una definici6n conceptual de la vecindad, que es adecuada

para examinar y pronosticar la respuesta reflejada en el comportamiento de 10s individuos, frente

a cambios en el medio ambiente que les rodea. Se basa en las percepciones de personas que viven

y/o invierten en una localidad especifica. La vecindad se define en tkrminos de espacio

exteriorizado: el area en la que 10s cambios ambientales iniciados por otros se percibe alterarhn

el bienestar que cualquier individuo obtiene de la localdad especifica. Luego, se desarrollan

algoritmos por medio de los cuales se pueden agregar las percepciones individuales, y se pueden

cuantificar diferencias en esas percepciones en dimensiones de tres escalas: congruencia,

generalidad y concordancia. Estas dimensiones miden el graso de consenso en 10s linderos de

espacios exteriorizados: 1) cuando se comparan a algdn lindero determinado anteriormente u

oficial, 2) para 10s individuos de una exteriorizaci6n dada, y 3) para 10s diversos tipos de

exteriorizaciones. En combinaci6n, estas dimensiones proveen un indicador cuadtitativo del punto

hasta el cual se puede definir una vecindad significativa con un cierto espacio. Se sugiere dmo

las especificaciones geogrhficas, operativas de una vecindad podrlan basarse en investigaciones

empfricas haciendo us0 de estos algoritmos. Finalmente, se discuten nuevos aspectos de las ideas

tradicionales de la vecindad, y las implicaciones para la politica, como consecuencia de la teorfa,

y se sugieren numerosas posibilidades para la investigaci6n empirica.

You might also like

- Syllabus Ethnography of Space and PlaceDocument12 pagesSyllabus Ethnography of Space and PlaceVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Method Statement of Static Equipment ErectionDocument20 pagesMethod Statement of Static Equipment Erectionsarsan nedumkuzhi mani100% (4)

- Constructing The Commons - Tom AvermaeteDocument9 pagesConstructing The Commons - Tom AvermaetePedro100% (2)

- Intermediate Accounting Testbank 2Document419 pagesIntermediate Accounting Testbank 2SOPHIA97% (30)

- Harvey D - Geographical Knowledge in The Eye of Power - Reflections On Derek Gregory's Geographical IDocument5 pagesHarvey D - Geographical Knowledge in The Eye of Power - Reflections On Derek Gregory's Geographical ILiza RNo ratings yet

- Vernacular Design and Global Commoditization Symbiotic RelationshipDocument15 pagesVernacular Design and Global Commoditization Symbiotic RelationshipscribdbangkokNo ratings yet

- Affective Urbanism. The Politics of Affect in Recent Urban DesignDocument54 pagesAffective Urbanism. The Politics of Affect in Recent Urban DesignAnarchivista100% (1)

- Postmodern Approaches To Space: Michiel Arentsen (0342653) Ruben Stam (0313092) Rick Thuijs (0312665)Document13 pagesPostmodern Approaches To Space: Michiel Arentsen (0342653) Ruben Stam (0313092) Rick Thuijs (0312665)Deni RohnadiNo ratings yet

- ECOLOGY INSPIRES PLANNINGDocument11 pagesECOLOGY INSPIRES PLANNINGShreyas SrivatsaNo ratings yet

- STS Chapter 5Document2 pagesSTS Chapter 5Cristine Laluna92% (38)

- 2016 04 1420161336unit3Document8 pages2016 04 1420161336unit3Matías E. PhilippNo ratings yet

- On the Nature of Neighbourhood: Exploring the ConceptDocument15 pagesOn the Nature of Neighbourhood: Exploring the ConceptsoydepaloNo ratings yet

- 1.1.2 Brenner Schmid - Toward A New Epistemology PDFDocument32 pages1.1.2 Brenner Schmid - Toward A New Epistemology PDFSofiDuendeNo ratings yet

- Education and Theatres 2019Document325 pagesEducation and Theatres 2019Alex RossiNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Normative, Understanding TechnologyDocument13 pagesUnderstanding The Normative, Understanding TechnologySamuel ZwaanNo ratings yet

- Merleau-Ponty's Phenomenological Philosophy of Mind and BodyDocument34 pagesMerleau-Ponty's Phenomenological Philosophy of Mind and BodyThangneihsialNo ratings yet

- Gadamer - Friendship and Solidarity-1Document17 pagesGadamer - Friendship and Solidarity-1Andrés MontenegroNo ratings yet

- Spatial Commons enDocument40 pagesSpatial Commons enNitika SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Colin Mcfarlane. Assemblage and Critical Urbanism. 2011Document22 pagesColin Mcfarlane. Assemblage and Critical Urbanism. 2011Marcos Burgos100% (1)

- GlocalizationDocument24 pagesGlocalizationLalita OuiNo ratings yet

- The City As A CommonsDocument12 pagesThe City As A CommonsFABIO JULIO MELO DA SILVANo ratings yet

- Farias 2011 The Politics of Urban Assemblages. SubmissionDocument11 pagesFarias 2011 The Politics of Urban Assemblages. SubmissionJohn_Doe_21No ratings yet

- Intangible and Tangible Heritage PDFDocument305 pagesIntangible and Tangible Heritage PDFJ-heart MalpalNo ratings yet

- UC Berkeley Document Explores Concept of Documentality Beyond Physical DocumentsDocument6 pagesUC Berkeley Document Explores Concept of Documentality Beyond Physical DocumentsJulio DíazNo ratings yet

- Lewis Mumford and The Architectonic S of Ecological CivilisationDocument333 pagesLewis Mumford and The Architectonic S of Ecological CivilisationChynna Camille FortesNo ratings yet

- Victims Perpetrators and Actors Revisite PDFDocument18 pagesVictims Perpetrators and Actors Revisite PDFAle LamasNo ratings yet

- Milton Santos A Pioneer in Critical Geography From The Global SouthDocument162 pagesMilton Santos A Pioneer in Critical Geography From The Global SouthmirianrconNo ratings yet

- Spaces of Capital/Spaces of Resistance: Mexico and the Global Political EconomyFrom EverandSpaces of Capital/Spaces of Resistance: Mexico and the Global Political EconomyNo ratings yet

- Trends in Architectural Design and AestheticsDocument18 pagesTrends in Architectural Design and AestheticsArchana M RajanNo ratings yet

- Spatial Expressions of Local Identity in The Times of Rapid Globalisation PaperDocument8 pagesSpatial Expressions of Local Identity in The Times of Rapid Globalisation Paperarh_mmilicaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Space Syntax in Identifying The Relationship Between Space and CrimeDocument10 pagesThe Role of Space Syntax in Identifying The Relationship Between Space and CrimeVương Đình HuyNo ratings yet

- Akinwumi - The Banality of The Immediate SpectacleDocument22 pagesAkinwumi - The Banality of The Immediate SpectaclesupercapitalistNo ratings yet

- Implementing Design Thinking in Organizations: An Exploratory StudyDocument16 pagesImplementing Design Thinking in Organizations: An Exploratory StudyKomal MubeenNo ratings yet

- Neil Brenner... Henri Lefebvre On State Space TerritoryDocument25 pagesNeil Brenner... Henri Lefebvre On State Space TerritoryGuilherme MarinhoNo ratings yet

- Social Justice ARTifaritiDocument12 pagesSocial Justice ARTifaritiFederico GuzmánNo ratings yet

- Marisol de La Cadena - Indigenous CosmopoliticsDocument37 pagesMarisol de La Cadena - Indigenous CosmopoliticsJosé RagasNo ratings yet

- Schatzki, T. (2011) - Where The Action Is: On Large Social Phenomena Such As Sociotechnical RegimesDocument31 pagesSchatzki, T. (2011) - Where The Action Is: On Large Social Phenomena Such As Sociotechnical RegimesbrenderdanNo ratings yet

- From Utopia To Non-Place. Identity and Society in The CityspaceDocument5 pagesFrom Utopia To Non-Place. Identity and Society in The CityspacespecoraioNo ratings yet

- Design Philosophy and Poetic Thinking: Peter Sloterdijk's Metaphorical Explorations of The InteriorDocument19 pagesDesign Philosophy and Poetic Thinking: Peter Sloterdijk's Metaphorical Explorations of The InteriorΦοίβηΑσημακοπούλουNo ratings yet

- Culture and Planning PDFDocument171 pagesCulture and Planning PDFArthur PeciniNo ratings yet

- The Pluriverse of Stefan Arteni's Painting IDocument35 pagesThe Pluriverse of Stefan Arteni's Painting Istefan arteniNo ratings yet

- The Civilizing Process and The History of Sexuality - Dennis SmithDocument23 pagesThe Civilizing Process and The History of Sexuality - Dennis Smitharv100% (1)

- Multifunctional LandscapeDocument27 pagesMultifunctional LandscapenekokoNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Imagined Communities - and BenedDocument6 pagesThe Importance of Imagined Communities - and BenedAssej Mae Pascua villaNo ratings yet

- Resilience, Adaptation and AdaptabilityDocument12 pagesResilience, Adaptation and AdaptabilityGuilherme AbuchahlaNo ratings yet

- Ecological Economics-Principles and Applications-7Document50 pagesEcological Economics-Principles and Applications-7Edwin JoyoNo ratings yet

- Tania Li - Practices of Assemblage and Community Forest ManagementDocument32 pagesTania Li - Practices of Assemblage and Community Forest ManagementAlejandro Alfredo HueteNo ratings yet

- Modernity at LargeDocument3 pagesModernity at LargeHelenasousamNo ratings yet

- Solutions in Multimedia and Hypertext. (P. 21-30) Eds.: Susan Stone and MichaelDocument15 pagesSolutions in Multimedia and Hypertext. (P. 21-30) Eds.: Susan Stone and Michaelsheetal tanejaNo ratings yet

- Rethinking The Urban Policy Agenda - OECDDocument315 pagesRethinking The Urban Policy Agenda - OECDHamilton ReporterNo ratings yet

- A Place Called Home PDFDocument12 pagesA Place Called Home PDFIssam MatoussiNo ratings yet

- Allegra Fryxell - Viewpoints Temporalities - Time and The Modern Current Trends in The History of Modern Temporalities - TEXT PDFDocument14 pagesAllegra Fryxell - Viewpoints Temporalities - Time and The Modern Current Trends in The History of Modern Temporalities - TEXT PDFBojanNo ratings yet

- Acculturation and Adaptation When Cultures MeetDocument10 pagesAcculturation and Adaptation When Cultures MeetStylesNo ratings yet

- Literature Review: IdeologyDocument11 pagesLiterature Review: IdeologyKyteNo ratings yet

- Definitions of Urban MorphologyDocument3 pagesDefinitions of Urban MorphologyChan Siew ChongNo ratings yet

- Cracking The Mirror On Kierkegaard's Concerns About Friendship - John LippitDocument21 pagesCracking The Mirror On Kierkegaard's Concerns About Friendship - John Lippittabris_chih_mxNo ratings yet

- BRENNER, Neil SCHMID, Christian - Towards A New Epistemology of The UrbanDocument32 pagesBRENNER, Neil SCHMID, Christian - Towards A New Epistemology of The UrbantibacanettiNo ratings yet

- Practice Spatial AgencyDocument9 pagesPractice Spatial AgencyJacquelineNo ratings yet

- Gaonkar Object and Method in Rhetorical CriticismDocument28 pagesGaonkar Object and Method in Rhetorical CriticismMichael KaplanNo ratings yet

- Massey Doreen - Space-Time, 'Science', and The Relation Between Physical Geography and Human GeographyDocument16 pagesMassey Doreen - Space-Time, 'Science', and The Relation Between Physical Geography and Human Geographycsy7aaNo ratings yet

- Neil Brenner and Christian Schmid ElemenDocument23 pagesNeil Brenner and Christian Schmid ElemenBensonSraNo ratings yet

- Spatial Configuration of Residential Area and Vulnerability of BurglaryDocument15 pagesSpatial Configuration of Residential Area and Vulnerability of BurglarybsceciliaNo ratings yet

- Information Cosmopolitics: An Actor-Network Theory Approach to Information PracticesFrom EverandInformation Cosmopolitics: An Actor-Network Theory Approach to Information PracticesNo ratings yet

- Panizza, Beyond Delegative DemocracyDocument28 pagesPanizza, Beyond Delegative DemocracyVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Globalization and Social Change in Latin AmericaDocument5 pagesGlobalization and Social Change in Latin AmericaVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Harvey Comunidad y Nuevo UrbanismoDocument3 pagesHarvey Comunidad y Nuevo UrbanismoVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Neighbourhood ParadigmDocument21 pagesNeighbourhood ParadigmVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Beijing Brief ContrerasDocument4 pagesBeijing Brief ContrerasVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Neighborhood Planning 2 PDFDocument5 pagesNeighborhood Planning 2 PDFVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Neoliberalism and Socialisation. GoughDocument22 pagesNeoliberalism and Socialisation. GoughVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Authoritarian Redevelopment in Santiago, Chile Power Relations in Urban Decision-Making: Neo-Liberalism, 'Techno-Politicians' Hugo Marcelo ZuninoDocument23 pagesAuthoritarian Redevelopment in Santiago, Chile Power Relations in Urban Decision-Making: Neo-Liberalism, 'Techno-Politicians' Hugo Marcelo ZuninoVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Globalization and Social Change in Latin AmericaDocument5 pagesGlobalization and Social Change in Latin AmericaVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- 1467-8330 00253Document22 pages1467-8330 00253rllandaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Urban History-1983-Gillette-421-44 PDFDocument25 pagesJournal of Urban History-1983-Gillette-421-44 PDFVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- The City Id Dead Long Live The NetDocument24 pagesThe City Id Dead Long Live The NetVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Prog Hum Geogr 2004 Lees 101 7Document8 pagesProg Hum Geogr 2004 Lees 101 7Veronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Llmado A Congreso Sobre Justicia EspacialDocument2 pagesLlmado A Congreso Sobre Justicia EspacialVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Urban History-1983-Gillette-421-44 PDFDocument25 pagesJournal of Urban History-1983-Gillette-421-44 PDFVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- The Relevance of Multilevel Statistical Methods For IdentifyingDocument7 pagesThe Relevance of Multilevel Statistical Methods For IdentifyingVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Planning History 2009 Lloyd Lawhon 111 32Document23 pagesJournal of Planning History 2009 Lloyd Lawhon 111 32Veronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Poverty Social Exclusion and NeighbourhoodDocument48 pagesPoverty Social Exclusion and NeighbourhoodVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- How Understand Nighbourhood RegenerationDocument19 pagesHow Understand Nighbourhood RegenerationVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Foster Care Entry Risk at ThreeDocument15 pagesA Comparison of Foster Care Entry Risk at ThreeVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Poverty Social Exclusion and NeighbourhoodDocument48 pagesPoverty Social Exclusion and NeighbourhoodVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- What Scale MattersDocument21 pagesWhat Scale MattersVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- A Brief Observational Measure For Urban NeighborhoodsDocument12 pagesA Brief Observational Measure For Urban NeighborhoodsVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Area-Based Initiatives The Rationale and Options For Area TargetingDocument78 pagesArea-Based Initiatives The Rationale and Options For Area TargetingVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- The Significanse of NeighbourhoodDocument9 pagesThe Significanse of NeighbourhoodVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Can We Spot A Neighborhood From The AirDocument14 pagesCan We Spot A Neighborhood From The AirVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- How Understand Nighbourhood RegenerationDocument19 pagesHow Understand Nighbourhood RegenerationVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- The Spatial Dimensions of Neighborhood EffectsDocument8 pagesThe Spatial Dimensions of Neighborhood EffectsVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Women, Neighbourhoods and Everyday LifeDocument15 pagesWomen, Neighbourhoods and Everyday LifeVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Farmers InterviewDocument5 pagesFarmers Interviewjay jariwalaNo ratings yet

- RoboticsDocument2 pagesRoboticsCharice AlfaroNo ratings yet

- Wordbank Restaurants 15Document2 pagesWordbank Restaurants 15Obed AvelarNo ratings yet

- Frequency Meter by C Programming of AVR MicrocontrDocument3 pagesFrequency Meter by C Programming of AVR MicrocontrRajesh DhavaleNo ratings yet

- Itec 3100 Student Response Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesItec 3100 Student Response Lesson Planapi-346174835No ratings yet

- Introduction to Human Resource Management Functions and Their ImportanceDocument23 pagesIntroduction to Human Resource Management Functions and Their ImportancedhrupaNo ratings yet

- TicketDocument2 pagesTicketbikram kumarNo ratings yet

- Discount & Percentage Word Problems SolutionsDocument4 pagesDiscount & Percentage Word Problems SolutionsrheNo ratings yet

- KL Wellness City LIvewell 360 2023Document32 pagesKL Wellness City LIvewell 360 2023tan sietingNo ratings yet

- Best Homeopathic Doctor in SydneyDocument8 pagesBest Homeopathic Doctor in SydneyRC homeopathyNo ratings yet

- cp2021 Inf03p02Document242 pagescp2021 Inf03p02bahbaguruNo ratings yet

- Camera MatchingDocument10 pagesCamera MatchingcleristonmarquesNo ratings yet

- 5030si PDFDocument2 pages5030si PDFSuperhypoNo ratings yet

- I-Parcel User GuideDocument57 pagesI-Parcel User GuideBrian GrayNo ratings yet

- SABIC Ethanolamines RDS Global enDocument10 pagesSABIC Ethanolamines RDS Global enmohamedmaher4ever2No ratings yet

- Siyaram S AR 18-19 With Notice CompressedDocument128 pagesSiyaram S AR 18-19 With Notice Compressedkhushboo rajputNo ratings yet

- Capran+980 CM en PDFDocument1 pageCapran+980 CM en PDFtino taufiqul hafizhNo ratings yet

- Data Collection Methods and Tools For ResearchDocument29 pagesData Collection Methods and Tools For ResearchHamed TaherdoostNo ratings yet

- Dubai Healthcare Providers DirectoryDocument30 pagesDubai Healthcare Providers DirectoryBrave Ali KhatriNo ratings yet

- Career Guidance Activity Sheet For Grade IiDocument5 pagesCareer Guidance Activity Sheet For Grade IiJayson Escoto100% (1)

- Stellar Competent CellsDocument1 pageStellar Competent CellsSergio LaynesNo ratings yet

- Examination: Subject CT5 - Contingencies Core TechnicalDocument7 pagesExamination: Subject CT5 - Contingencies Core TechnicalMadonnaNo ratings yet

- Presentation of The LordDocument1 pagePresentation of The LordSarah JonesNo ratings yet

- Responsibility Centres: Nature of Responsibility CentersDocument13 pagesResponsibility Centres: Nature of Responsibility Centersmahesh19689No ratings yet

- PNW 0605Document12 pagesPNW 0605sunf496No ratings yet

- Hollow lateral extrusion process for tubular billetsDocument7 pagesHollow lateral extrusion process for tubular billetsjoaopedrosousaNo ratings yet