Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Communications Blindspot

Uploaded by

Ernesto Bulnes0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

35 views3 pagesDallas Smythe was a founding figure in the establishment of critical / Marxist Political Economy of communication. He stressed the importance of studying media and communication in a critical and non-administrative way. This chapter explores perspectives for the Marxist study of media and communication today.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentDallas Smythe was a founding figure in the establishment of critical / Marxist Political Economy of communication. He stressed the importance of studying media and communication in a critical and non-administrative way. This chapter explores perspectives for the Marxist study of media and communication today.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

35 views3 pagesCommunications Blindspot

Uploaded by

Ernesto BulnesDallas Smythe was a founding figure in the establishment of critical / Marxist Political Economy of communication. He stressed the importance of studying media and communication in a critical and non-administrative way. This chapter explores perspectives for the Marxist study of media and communication today.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

Western Marxism communications

In 1977, Dallas Smythe published his seminal article Communications: Blindspot

of Western Marxism (Smythe 1977a), in which he argued that Western Marxism

has not given enough attention to the complex role of communications in

capitalism. The articles publication was followed by an important foundational

debate of media sociology that came to be known as the Blindspot Debate

(Murdock 1978, Livant 1979; Smythe answered with a rejoinder to Murdock:

Smythe 1994, 292299) and by another article of Smythes on the same topic !

(On the Audience Commodity and Its Work in: Smythe 1981, 2251). More

than 30 years have passed and the rise of neo-liberalism resulted in a turn away

from the interest in class and capitalism and brought about the rise of postmode

rnism

and the logic of the commodification of everything: Marxism became the

blind spot of the social sciences.

The task of this chapter is to explore perspectives for the Marxist study of

media and communication today. First, I discuss the importance of taking a Marxi

st

approach for studying media and communication (section 4.2). Second, I give

a short overview of the audience commodity, its audience labour debate and its

renewal (section 4.3). Dallas Smythe made important contributions to a labour

theory of the audience that can today be used for grounding a digital labour the

ory

of value. In section 4.4, I analyse social media capital accumulation with the

help of the notion of Internet prosumer commodification. Section 4.5 provides

an overview of ideological changes that relate to digital media, perceived chang

es

and the relationship between play and labour in contemporary capitalism (playbou

r).

Section 4.6 presents a critique of criticisms of the digital labour debate.

Finally, I draw some conclusions.

!

!

4.2. The Importance of Critical Political Economy,

Critical Theory and Dallas Smythe

!

Dallas Smythe was a founding figure in the establishment of Critical/Marxist

Political Economy of Communication and taught the first course in the field

(Mosco 2009, 82). He stressed the importance of studying media and communication

in a critical and non-administrative way: By critical researchable problems

we mean how to reshape or invent institutions to meet the collective needs of th

e

relevant social community. [. . .] By critical tools, we refer to historical, mate

rialist

analysis of the contradictory process in the real world. By administrative ideolog

y,

we mean the linking of administrative-type problems and tools, with interpretati

on

of results that supports, or does not seriously disturb, the status quo. By criti

cal

ideology, we refer to the linking of critical researchable problems and critical

tools with interpretations that involve radical changes in the established order

(Smythe and Dinh 1983, 118).

In the article On the Political Economy of Communications, Smythe defined

the central purpose of the study of the political economy of communications

as the evaluation of the effects of communication agencies in terms of

the policies by which they are organised and operated and the analysis of the

structure and policies of these communication agencies in their social settings

(Smythe 1960, 564). He identified various communications policy areas in this

article.Whereas there are foundations of a general political economy in this cha

pter,

there are no traces of Marx in it. Janet Wasko (2004, 311) argues that although

Smythes discussion at this point did not employ radical or Marxist terminology,

it was a major departure from the kind of research that dominated the study of m

ass communications at that time. Wasko points out that it was in the 1970s

that the political economy of media and communications (PE/C) was explicitly

defined again but this time within a more explicitly Marxist framework

(ibid., 312). She mentions in this context the works of Nicholas Garnham, Peter

Golding, Armand Mattelart, Graham Murdock and Dallas Smythe as well as the

Blindspot Debate (ibid., 312313).

Later, Smythe (1981) formulated explicitly the need for a Marxist Political

Economy of Communications. He spoke of a Marxist theory of communication

(Smythe 1994, 258) and that critical theory means Marxist or quasi-

Marxist theory (ibid., 256). He identified eight core aspects of a Marxist politi

cal

economy of communications (Smythe 1981, xvixviii):

!

(1) materiality,

(2) monopoly capitalism,

(3) audience commodification and advertising,

(4) media communication as part of the base of capitalism,

(5) labour-power,

(6) critique of technological determinism,

(7) the dialectic of consciousness, ideology and hegemony on the one side and

material practices on the other side, and

(8) the dialectics of arts and science.

!

!

Smythe reminds us of the importance of the engagement with Marxs works for

studying the media in capitalism critically. He argued that Gramsci and the Fran

kfurt

School advanced the concepts of ideology, consciousness and hegemony as

areas saturated with subjectivism and positivism (ibid., xvii). These Marxist

thinkers would have advanced an idealist theory of the communications commodity

(Smythe 1994, 268) that situates the media only on the superstructure

of capitalism and forgets to ask what economic functions they serve in capitalis

m.

In a review of Hans Magnus Enzensbergers (1974) book The Consciousness

Industry, Smythe on the one hand agreed with Enzensberger that the mind

industry wants to sell the existing order, but on the other hand disagreed

with the assumption that its main business and concern is not to sell its product

(Enzensberger 1974, 10): Enzensbergers theory that every social systems

communications policy serves the controlling class interest in perpetuating that

system is of course correct, but to say that the mass media and consciousness

industry have no product would mean to identify commodity production with

crude physical production (Smythe 1977b, 200). Smythe (1977b) characterizes

Enzensbergers views as bourgeois, idealistic and anarcho-liberal. For Smythe

(1994, 266291), the material aspect of communications is that audiences work,

are exploited and are sold as commodity to advertisers. He was more interested

in aspects of surplus value generation of the media than their ideological effec

ts.

So Smythe called for analysing the media more in terms of surplus value and

exploitation and less in terms of manipulation. Nicholas Garnham (1990, 30)

shares with Smythe the insight that the Political Economy of Communications

should shift attention away from the conception of the mass media as ideological

apparatuses and focus on the analysis of their economic role in surplus

value generation and advertising.The analysis of media as vehicles for ideologica

l

domination is for Garnham (2004, 94) a busted flush that is not needed for

explaining the relatively smooth reproduction of capitalism.

Given the analyses of Smythe and Garnham, the impression can be created

that Frankfurt School critical theory focuses on ideology critique and

the Political Economy of Media/Communications on the analysis of capital

accumulation by and with the help of the media. This is however a misunderstandi

ng.

Although widely read works of the Frankfurt School focused on

ideology (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford 1950; Horkheimer

and Adorno 2002; Marcuse 1964), other books in its book series Frankfurter Beitrg

e

zur Soziologie dealt with the changes of accumulation in what was termed

late capitalism or monopoly capitalism (for example, Pollock 1956, Friedmann

1959).The Marxist political economist Henryk Grossmann was one of the most

important members of the Institut fr Sozialforschung in the 1920s and wrote

his main work at the institute (Grossmann 1929). Although only few will today

agree with Grossmanns theory of capitalist breakdown, it remains a fact that

Marxist political economy was an element of the Institut fr Sozialforschung

right from its beginning and had in Pollock and Grossmann two important represen

tatives.

After Max Horkheimer became director of the institute in 1930,

he formulated an interdisciplinary research programme that aimed at bringing

together philosophers and scholars from a broad range of disciplines, including

economics (Horkheimer 1931). When formulating their general concepts of

critical theory, both Horkheimer (2002, 244) and Marcuse (1941) had a combinatio

n

of philosophy and Marxs critique of the political economy in mind.

Just like Critical Political Economy was not alien to the Frankfurt School,

ideology critique has also not been alien to the approach of the Critical Politi

cal

Economy of the Media and Communication. For Graham Murdock and

Peter Golding (1974, 4), the media are organizations that produce and distribute

commodities, are means for distributing advertisements and also have an

ideological dimension by disseminating ideas about economic and political

structures. Murdock (1978, 469) stressed in the Blindspot Debate that there are

non-advertising-based culture industries (like popular culture) that sell explana

tions

of social order and structured inequality and work with and through

ideologyselling the system (see also Artz 2008, 64). Murdock (1978) argued in

the Blindspot Debate that Smythe did not enough acknowledge Western Marxism

in Europe and that one needs a balance between ideology critique and political

economy for analysing the media in capitalism.

You might also like

- This Is The Second TimeDocument1 pageThis Is The Second TimeErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- Digital Futures For Cultural and Media StudiesDocument4 pagesDigital Futures For Cultural and Media StudiesErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Lenin and LeninismDocument5 pagesAn Introduction To Lenin and LeninismErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- Inedit Interview With Michel Foucault 1979Document19 pagesInedit Interview With Michel Foucault 1979Ernesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- Cultural StudiesDocument3 pagesCultural StudiesErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- Money and PriceDocument3 pagesMoney and PriceErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- Surplus ValueDocument4 pagesSurplus ValueErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- The Connection of CapitalismDocument6 pagesThe Connection of CapitalismErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- Surplus ValueDocument4 pagesSurplus ValueErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- Exchange ValueDocument2 pagesExchange ValueErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- Political Subjectivity Is Revolutionary SubjectivityDocument5 pagesPolitical Subjectivity Is Revolutionary SubjectivityErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- Chapter OnDocument3 pagesChapter OnErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- Ideology, Play and Digital LabourDocument6 pagesIdeology, Play and Digital LabourErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- Cultural Studies in The Future TenseDocument4 pagesCultural Studies in The Future TenseErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- Frankfurt School taxes and ideology critiqueDocument5 pagesFrankfurt School taxes and ideology critiqueErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- Work in CommunismDocument3 pagesWork in CommunismErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- Robert BermanDocument1 pageRobert BermanErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- Work and Labour in SocietyDocument3 pagesWork and Labour in SocietyErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- The Need For Studying Digital LabourDocument3 pagesThe Need For Studying Digital LabourErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- EuropocalypseDocument2 pagesEuropocalypseErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- Work As A Necessary Element of All SocietiesDocument3 pagesWork As A Necessary Element of All SocietiesErnesto BulnesNo ratings yet

- Roghoff and Reinhardt - NBER Paper This Time Is DifferentDocument124 pagesRoghoff and Reinhardt - NBER Paper This Time Is DifferentKRambis79No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Pathways-Childrens Ministry LeaderDocument16 pagesPathways-Childrens Ministry LeaderNeil AtwoodNo ratings yet

- Lignan & NeolignanDocument12 pagesLignan & NeolignanUle UleNo ratings yet

- AWK and SED Command Examples in LinuxDocument2 pagesAWK and SED Command Examples in Linuximranpathan22No ratings yet

- Optimum Work Methods in The Nursery Potting ProcessDocument107 pagesOptimum Work Methods in The Nursery Potting ProcessFöldi Béla100% (1)

- Chapter One: Business Studies Class XI Anmol Ratna TuladharDocument39 pagesChapter One: Business Studies Class XI Anmol Ratna TuladharAahana AahanaNo ratings yet

- Developmen of Chick EmbryoDocument20 pagesDevelopmen of Chick Embryoabd6486733No ratings yet

- VFD ManualDocument187 pagesVFD ManualgpradiptaNo ratings yet

- Reaction CalorimetryDocument7 pagesReaction CalorimetrySankar Adhikari100% (1)

- Where Are The Women in The Water Pipeline? Wading Out of The Shallows - Women and Water Leadership in GeorgiaDocument7 pagesWhere Are The Women in The Water Pipeline? Wading Out of The Shallows - Women and Water Leadership in GeorgiaADBGADNo ratings yet

- ABRAMS M H The Fourth Dimension of A PoemDocument17 pagesABRAMS M H The Fourth Dimension of A PoemFrancyne FrançaNo ratings yet

- 10CV54 Unit 05 PDFDocument21 pages10CV54 Unit 05 PDFvinodh159No ratings yet

- Skype Sex - Date of Birth - Nationality: Curriculum VitaeDocument4 pagesSkype Sex - Date of Birth - Nationality: Curriculum VitaeSasa DjurasNo ratings yet

- BILL of Entry (O&A) PDFDocument3 pagesBILL of Entry (O&A) PDFHiJackNo ratings yet

- IS 2848 - Specition For PRT SensorDocument25 pagesIS 2848 - Specition For PRT SensorDiptee PatingeNo ratings yet

- Yamaha RX-A3000 - V3067Document197 pagesYamaha RX-A3000 - V3067jaysonNo ratings yet

- Working With Session ParametersDocument10 pagesWorking With Session ParametersyprajuNo ratings yet

- Machine Tools Cutting FluidsDocument133 pagesMachine Tools Cutting FluidsDamodara MadhukarNo ratings yet

- Expected OutcomesDocument4 pagesExpected OutcomesPankaj MahantaNo ratings yet

- Costos estándar clase viernesDocument9 pagesCostos estándar clase viernesSergio Yamil Cuevas CruzNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2: Lesson Plan Analysis, Revision and Justification - Kaitlin Rose TrojkoDocument9 pagesAssignment 2: Lesson Plan Analysis, Revision and Justification - Kaitlin Rose Trojkoapi-408336810No ratings yet

- ASCP User GuideDocument1,566 pagesASCP User GuideThillai GaneshNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document2 pagesChapter 1Nor-man KusainNo ratings yet

- What Is Chemical EngineeringDocument4 pagesWhat Is Chemical EngineeringgersonNo ratings yet

- The Collected Letters of Flann O'BrienDocument640 pagesThe Collected Letters of Flann O'BrienSean MorrisNo ratings yet

- Primary Homework Help Food ChainsDocument7 pagesPrimary Homework Help Food Chainsafnaxdxtloexll100% (1)

- 01 WELD-2022 Ebrochure 3Document5 pages01 WELD-2022 Ebrochure 3Arpita patelNo ratings yet

- Rpo 1Document496 pagesRpo 1Sean PrescottNo ratings yet

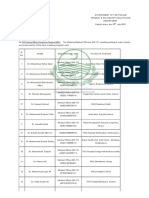

- Government of The Punjab Primary & Secondary Healthcare DepartmentDocument3 pagesGovernment of The Punjab Primary & Secondary Healthcare DepartmentYasir GhafoorNo ratings yet

- Eating and HealingDocument19 pagesEating and HealingMariana CoriaNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument15 pagesResearch PapershrirangNo ratings yet