Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Damage Control Surgery Unstable Pelvic Fracture (Injury)

Uploaded by

Abdur Rachman Ba'abdullahOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Damage Control Surgery Unstable Pelvic Fracture (Injury)

Uploaded by

Abdur Rachman Ba'abdullahCopyright:

Available Formats

Damage control orthopaedics in unstable pelvic

ring injuries

P.V. Giannoudis

a,

*, H.C. Pape

b

a

Departments of Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery, St. Jamess University Hospital,

University of Leeds, Leeds LS9 7TF, UK

b

Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany

Introduction

Pelvic fractures account for 38% of all skeletal

fractures.

31,40

They are usually secondary to high-

energy trauma with motor vehicle crashes being the

commonest mechanism of injury.

Despite the introduction of organised trauma

systems, pelvic ring disruptions continue to be a

signicant source of morbidity and mortality ran-

ging from 4.8 to 50%.

10,14,44

Their management in

the acute setting is challenging to the most experi-

enced trauma surgeons and often requires a multi-

disciplinary approach involving a variety of special-

ties. This is due to the presence of associated

injuries as the high-energy force applied to the

pelvic ring is also distributed to other parts of the

skeleton resulting in injuries to other organs.

42

Appropriate assessment and treatment of these

fractures is important because it can lead in fewer

deaths and less long-term disability.

Several classication systems have been devel-

oped over the years based on fracture location,

pelvic stability, injury mechanism and direction

of injury force applied.

The Young and Burgess classication system is an

expansion of the original classication developed by

Pennal and Sutherland where the fractures were

classied based on the direction of three possible

injury forces: anterior posterior compression (APC),

lateral compression (LC) and vertical shear (VS).

8,57

Young and Burgess developed subsets on the LC and

APC injuries to quantify the forces applied. They

also added a forth injury force category of com-

bined mechanical injury.

6

Their classication sys-

tem helps with the detection of the posterior ring

injury, predicts local and distant associated inju-

ries, resuscitation needs and expected mortality

rates. APC types II and III, lateral compression type

Injury, Int. J. Care Injured (2004) 35, 671677

KEYWORDS

Orthopaedics;

Pelvic ring injury;

Skeletal fracture

Summary Pelvic ring injuries are often associated with other system injuries and

require a multidisciplinary approach for their treatment. Early mortality is usually

secondary to uncontrolled haemorrhage whereas late mortality is due to associated

injuries and sepsis-induced multiple organ failure. The management of the pelvic

fracture should be conceived as part of the resuscitative effort as errors in early

management may lead to signicant increases in mortality.

In severely multiple injured patients who are in an unstable or in extremis

clinical condition damage control orthopedics is the current treatment of choice.

By performing limited surgical interventions the subsequent reduction in blood loss

and transfusion requirements can only be benecial in these critically ill patients,

reducing the risk of developing systemic complications and early mortality.

2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

*Corresponding author. Tel.: 44-113-2065084;

fax: 44-113-2065156.

E-mail address: pgiannoudi@aol.com (P.V. Giannoudis).

00201383/$ see front matter 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.injury.2004.03.003

III, vertical shear (VS) and combined mechanical

injuries are indicative of major ligament disruption.

AP III injuries require the most blood replacement,

followed by VS patterns followed by CM followed by

LC III injuries.

6

Patients with pelvic fractures can be divided into

two sub-groups. The rst of those are patients who

sustain stable pelvic fractures with most of the

injury conned to the ligamentous tissues. Manage-

ment in these circumstances is conned to recon-

struction of the osteo-ligamentous structures on a

more semi-elective basis.

In the second group, patients sustain displaced

pelvic ring fractures, require emergency haemor-

rhage control and a multidisciplinary teamapproach

for the associated injuries. The overall prevalence

of pelvic fractures presenting with haemodynamic

instability has been reported to range from 2 to

20%.

4,16,25,32,41,43

Errors in early management may

lead to signicant increases in mortality. Early

recognition and appropriate management of

patients within this group can therefore offer sig-

nicant improvements in outcome.

The management of this specic sub-group of

patients has evolved over the years to what is known

today damage control orthopaedics.

Control of pelvic instability and

haemorrhage

During the acute phase, the goal of treatment of

high-energy pelvic ring disruptions is prevention of

early death from haemorrhage. The management of

internal blood loss is paramount initially.

Arterial bleeding (iliac vessels and their branches

to the inferior abdominal viscera and pelvic organs)

is a major contributor to haemorrhagic shock in

pelvic fractures (Fig. 1). Other sources of bleeding

include the low-pressure venous plexus and frac-

tured cancellous bone surfaces. The retroperito-

neum can contain up to 4 L of blood and bleeding

will continue until intra-vascular pressure is over-

come and physiological tamponade has occurred.

However, where extensive disruption of the retro-

peritoneal muscle compartments has taken place

this can lead to uncontrolled haemorrhage with the

risk of exsanguination. This is because the retro-

peritoneum is not a closed space and pressure

induced tamponade cannot be expected.

20

The rst step in restoring haemodynamic stability

includes the administration of intravenous crystal-

loid uids and whole blood. When replacement of

uid and blood does not stabilise the patients vital

signs, additional steps must be taken. Any subse-

quent interventions should be rapid and minimally

traumatic focusing on haemorrhage control and

other life saving measures. Complex reconstructive

work is delayed until the patient is haemodynami-

cally stable and in a better physiological condition

to withstand the additional surgical burden. Avoid-

ance of coagulation disturbances, the systemic

inammatory response, adult respiratory distress

syndrome and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

is of paramount importance for reduced mortality

rates.

17,18,34

In general terms treatment should be highly case-

dependent. Treatment options that should be con-

sidered for the emergency haemostasis of patients

with pelvic fractures at risk of exsanguination

include the pelvic sling, arterial inow arrest,

external xation devices, internal xation, direct

surgical haemostasis, pelvic packing, pelvic angio-

graphy and embolisation.

Pelvic sling

During the past decade the use of a bed sheet, pelvic

sling and pelvic belt for emergency stabilization of

pelvic fractures has found great acceptance as it

achieves adequate compression without compro-

mising access to the patient.

3,9,45

Prophylactic application of these devices at the

scene or in the Emergency Department appears to

be satisfactory. Furthermore, they are easy to use,

readily available and inexpensive. However, poten-

tial disadvantages may be related to soft-tissue

pressure and the risk of visceral injury or sacral

nerve root compression, though there are no

reported complications in the available small clin-

ical series.

49,53

Arterial inow arrest

In cases where exsanguination of the patient is

imminent, occlusion of the aorta can be used as a

temporary measure to control the haemorrhage.

This can be performed directly open cross clamping

or via percutaneous or open balloon catheter Figure 1 Pelvic fractures and arterial bleeding.

672 P.V. Giannoudis, H.C. Pape

techniques.

5

Other authors have reported satisfac-

tory control of arterial bleeding with ligation of the

hypogastric artery attributing this to the remark-

able collateral supply within the pelvis.

37,47

External xator devices

Various external xation devices have been devel-

oped over the years and rely on pin insertion into the

iliac crest. An external xator is probably the most

commonly used tool worldwide for rapid pelvic ring

stabilization providing resuscitative, provisional

and denitive treatment. It is considered as the

treatment of choice especially in cases where asso-

ciated extensive soft tissue injuries are present

including, bowel and bladder disruptions.

51,56

External xator systems are usually easy to han-

dle and can be applied in the trauma room. Their

application controls blood loss by direct compres-

sion at the fracture site and pressure on the injured

vessels. Correct pin placement is the foundation of

the pelvic external xator. Resuscitation frames

usually involve the application of two pins per iliac

crest.

43,54

Many of the clinical complications asso-

ciated with pelvic external xation are related to

the iliac crest pins and the high rate of secondary

displacement in type B and C injuries.

29

Pelvic C-clamp

The C-clamp consists of two pins is applied on the

posterior ilium in the region of the SI joints. It

provides compression and stability at the posterior

aspect of the ring at the point where the greatest

bleeding usually occurs and thus provides effective

pelvic tamponade. Its use however may be compro-

mised in the presence of fractures of the ilium and

trans-iliac fracture dislocations.

15

Potential compli-

cations include iatrogenic injury to the gluteal neu-

rovascular structures and secondary nerve injury as

a result of over-compression in sacral fractures.

38

Several reports have highlighted their effectiveness

especially in the acute clinical setting.

39,50

Internal xation

The option of open reduction and internal xation is

considered as the procedure of choice for pelvic ring

xation due to clearly superior biomechanical

advantages. However, in the acute setting and

especially in the extremis clinical condition of

the patient such an approach is not advocated as

it is time consuming and often extensile approaches

are necessary predisposing the patient to uncontrol-

lable haemorrhage, coagulation disturbances and

early mortality. When haemodynamic stability has

been achieved, only then symphyseal plating, ante-

rior plating of the SI-joint and application of trans-

iliosacral screws is sensible.

1,27,46

Direct surgical haemostasis

Direct surgical haemostasis whilst providing a the-

oretical advantage, in the real clinical environment

it is not usually feasible as bleeding is often sec-

ondary to damaged venous plexuses and control of

haemorrhage may be unachievable. Furthermore

uncontrolled circumferential stitching and clip

application, with inadequate visualization, may

lead to iatrogenic nerve injuries.

2,13

Pelvic angiography and embolisation

Haemodynamic compromise following unstable pel-

vic fractures secondary to arterial bleeding is pre-

sent in only about 10% of the cases.

23,24

The use of

angiographic pelvic vessel embolisation in trau-

matic pelvic bleeding remains a topic of intense

discussion. Its efcacy has been questioned as mor-

tality gures of up to 50% have been reported

despite effective bleeding control.

7,21

Further-

more, as the procedure can be time consuming,

management of other associated injuries may be

problematical.

In his study, Cook et al. emphasised the impor-

tance of the application of an external xator prior

to pelvic angiography. Out of 23 patients who were

subjected to embolisation, 10 patients died (43%)

and 6 of these had their angiography as the primary

therapeutic intervention. Of these, ve had frac-

tures that would have been stabilized by an external

xator. The authors recommend external pelvic

xation prior to pelvic angiography.

7

In another study, Velmahos et al. reported on 30

patients who underwent bilateral internal iliac artery

embolisation. In 17 patients embolisation was per-

formed as the primary treatment for haemorrhage

control whereas in the remaining 13 patients it was

performed as a secondary treatment as they had rst

undergone laparotomy with unsuccessful control of

the bleeding. The overall success rate was 97% and

the authors concluded that the procedure appeared

to be useful in a selected group of patients.

52

Hamill et al. studied 20 out of 76 patients with

pelvic trauma who underwent pelvic embolisation

with a primary success rate of 90%. The average

time from injury to angiography was 5 h (2.323 h).

In eight patients (40%) a second procedure due to

ongoing haemorrhage was required, four of these

patients died.

21

In order for pelvic angiography and embolisation

to be successful, interventional radiologists familiar

Damage control orthopaedics in unstable pelvic ring injuries 673

with the procedure and dedicated facilities should be

readily available at the receiving hospital minimizing

the time between admission and performance of the

procedure. In recent studies an improved results

have been reported with the average time to inter-

vention decreasing from 17 h

19,22

to 5 h.

35

Pelvic packing

The technique of retroperitoneal packing has been

successfully used in some institutions where tam-

ponades are applied in the paravesical and presacral

spaces in an attempt to tamponade bleeding.

Immediate posterior pelvic ring stabilization with

the pelvic C-clamp or an external xator provides

mechanical stability for pelvic tamponade and frac-

ture reduction leads to a reduction in fracture

haemorrhage. The presacral and paravesical regions

are then packed from posterior to anterior using

standard surgical techniques. The packing is chan-

ged or removed 48 h after injury.

Ertel et al. prospectively analyzed 20 consecu-

tive patients with pelvic ring disruption and hae-

morrhagic shock. All patients were treated with an

immediate pelvic C-clamp followed by laparotomy

and pelvic packing in persistent or massive haemor-

rhage. The overall mortality rate was 25%. Haemor-

rhagic shock was identied by blood lactate levels

at admission, which was on average 5.1 mmol/l. A

mean of 33.2 units of blood transfusion were

required within the rst 12 h.

12

In another study, 41 patients in an extremis

clinical condition were analysed.

11

The average ISS

was 40 and the average volume of blood transfused

was 33.9 units. Concomitant injuries were common

with 66% having head injuries, 73% chest injuries,

61% abdominal injuries and 88% extremity injuries.

Emergency treatment consisted of 9 crash thoraco-

tomies, 23 crash laparotomies, 9 aortic clampings to

control haemorrhage and 2 pelvic C-clamp applica-

tions. Effective angiographic embolisation was per-

formed in one patient. The overall mortality rate of

these patients was 90.2%. The majority of patients

(56%) died within 24 h due to persistent haemor-

rhagic shock.

11

Whilst some authors have attempted to provide

comparisons between the efcacy of pelvic packing

versus pelvic angiography, one could say that such a

comparison is not appropriate.

It is apparent from the data that the two groups

of patients undergoing pelvic packing or embolisa-

tion are not comparable. The average time to inter-

vention is far lower in the pelvic packing group and a

signicantly higher volume of PRBC transfusion was

necessary for immediate resuscitation. The overall

average transfusion rate for patients who under-

went embolisation was 1.65 units of blood/h

7,21

and

this is in contrast to those who underwent emer-

gency pelvic packing, receiving on average 8 units in

the rst hour or 12 in the rst 2 h.

50

These patients

represent a group of extremely unstable patients

suffering massive pelvic bleeding with an expect-

edly high mortality rate.

Damage control orthopaedics for pelvic

fractures with haemodynamic

instability

Mortality from pelvic fractures could be divided to

early, secondary to uncontrolled haemorrhage, and

late due to post-traumatic complications such as

ARDS/MODS.

12,50

It is clear today that the develop-

ment of ARDS and MODS is due to multiple altera-

tions in inammatory and immunological functions,

which occur shortly after trauma and haemorrhage

(rst hit phenomena). Traumatic injury leads to

systemic inammation (Systemic Inammatory

Response Syndrome or SIRS) followed by a period

of recovery mediated by a counter-regulatory anti-

inammatory response (CARS).

33

Severe inamma-

tion may lead to acute organ failure and early death

after injury but a lesser inammatory response

followed by excessive CARS may induce a prolonged

immunosuppressed state that can also be deleter-

ious to the host.

The surgical burden (operative intervention, sec-

ond hit phenomena) on the immune response that

occurs in polytraumatized patients, in addition to

that caused by the primary insult, is considered today

as a critical factor directly affecting the clinical

course of the patient.

34

Sub-clinical consequences

of the initial trauma and subsequent operative treat-

ment could manifest as abnormalities in organ

function, leading to MODS. It is believed today

that the burden of the second hit should be mini-

mized in multiply injured patients with a high risk of

adverse outcome. There is no doubt that prolonged

operative interventions on polytrauma patients can

lead to coagulation disturbances and an abnormal

immuno-inammatory state causing remote organ

injury.

26,55

In patients with pelvic fractures being

in an unstable or extremis clinical condition

therefore, prolonged operative interventions could

initiate a series of reactions at the molecular level

predisposing the patient to an adverse outcome. Any

surgical intervention here must be considered imme-

diately life saving and should therefore be simple,

quick and well performed. Rigid rules relating to

timing should be avoided to prevent unnecessary

delay time is usually critical to survival of the

patient.

18

Protocols designed to reduce mortality

674 P.V. Giannoudis, H.C. Pape

should stop bleeding, detect and control associated

injuries and restore haemodynamics. A staged diag-

nostic and therapeutic approach is required. During

the rst 24 h, death from exsanguination has been

identied as a major cause of mortality. The severity

of bleeding is a crucial hallmark for survival during

the early period after injury. In young patients who

are able to compensate for extensive blood loss for

several hours, underestimation of the true haemo-

dynamic status can lead to fatal outcome. Because of

the disastrous haemodynamic conditions of these

patients, only external devices that are easy to apply

can be used effectively. These devices, by external

compression reduce the intrapelvic volume and cre-

ate a tamponade effect against ongoing bleeding.

They also restore stability and bone contact to the

posterior elements of the pelvis and contribute to

blood clotting. Pelvic packing should be considered

in cases where, despite the application of the exter-

nal xator, ongoing bleeding is encountered. In this

situation, angiographic embolisation is both time

consuming and inhibitive to dynamic assessment

and further treatment. Pelvic packing allows the

simultaneous assessment and treatment of abdom-

inal injuries. In the presence of multiple massive

bleeding points, tamponade of the areas or tempor-

ary aortic compression should be considered. Com-

plex reconstructive procedures in the abdomen

should be avoided in the presence of pelvic haemor-

rhage. A major splenic rupture usually necessitates

splenectomy. In liver injuries, attention is paid only

to major vessels and hepatic tamponade is applied.

Bowel injuries are clamped and covered and deni-

tive treatment performed after the haemodynamic

situation is stabilized.

28,30,36,48

Angiographic embolisation is not usually indi-

cated in this patient population. However, in cases

where haemodynamic stability with volume repla-

cement can be achieved but ongoing pelvic hae-

morrhage is suspected (expanding haematoma)

then angiography could be considered as an adjunct

to the treatment protocol.

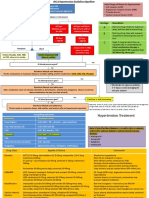

Damage control orthopedics is the current treat-

ment of choice for the severely injured patient

especially those with an unstable pelvic ring injury

associated with haemodynamic instability (Fig. 2).

The management of the pelvic fracture should be

conceived as part of the resuscitative effort. By

maintaining circulating blood volume and tissue

oxygenation, whilst performing a rapid and limited

surgical intervention where indicated, the damage

induced by any procedure is minimized. Immediate

external xation of the unstable pelvis with pelvic

packing to control pelvic haemorrhage is a practical

approach in those in extremis and borderline

patients. Angiographic embolisation can only be

recommended in the more stable patient.

The recognized benets of pelvic fracture stabi-

lization are obtained at an early stage. The subse-

quent reduction in blood loss and transfusion

requirements can only advantage these critically

ill patients and reduce the risks of developing sys-

temic complications.

References

1. Barei DP, Bellabarba C, Mills WJ, et al. Percutaneous

management of unstable pelvic ring disruptions. Injury

2001;32:SA3344.

Management of Pelvic Fractures

Clinical Condition of Patient

Stable Borderline Unstable In extremis

Cause of haemorrhage

(chest abdomen)?

Re-evaluation

2

nd

FAST

Stable OR

ORIF ORIF

Uncertain/OR

DCO

Ex Fix C-clamp

Ex-fix/C-clamp

Packing

OR

DCO

If continuously unstable:

Extrapelvic bleeding sources ?

Pelvic haemorrhage

Angiography

Yes No

OR

Repacking /ITU

Figure 2 Damage control orthopaedics (DCO) in unstable pelvic fractures.

Damage control orthopaedics in unstable pelvic ring injuries 675

2. Beard J, Davidson C. Pelvic injuries associated with

traumatic abduction of the leg. Injury 1988;19:3536.

3. Bottlang M, Simpson T, Sigg J, et al. Noninvasive reduction

of open-book pelvic fractures by circumferential compres-

sion. J Orthop Trauma 2002;16:36773.

4. Buckle R, Browner B, Morandi M. Emergency reduction

for pelvic ring disruptions and control of associated

hemorrhage using the pelvic stabilizer. Tech Orthop 1995;

9:25866.

5. Buhren V, Trentz O. Intraluminare Ballonblockade der Aorta

bei traumatischer Massivblutung. Unfallchirurg 1989;92:

30913.

6. Burgess AR, Eastridge BJ, Young JWR, et al. Pelvic ring

disruptions: effective classication system and treatment

protocols. J Trauma 1990;30:84856.

7. Cook RE, Keating JF, Gillespie I. The role of angiography in

the management of haemorrhage from major fractures of

the pelvis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002;84:17882.

8. Dalal SA, Burgess AR, Siegel JH, et al. Pelvic fracture in

multiple trauma: classication by mechanism is key to

pattern of organ injury, resuscitative requirements and

outcome. J Trauma 1989;29:9811002.

9. Duxbury M, Rossiter N, Lambert A. Cable ties for pelvic

stabilisation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2003;85:1304.

10. Eastridge BJ, Burgess AR. Pedestrian pelvic fractures: 5 year

experience of a major urban trauma center. J Trauma

1997;42:695700.

11. Ertel W, Eid K, Keel M, et al. Therapeutical strategies and

outcome of polytraumatized patients with pelvic injuriesa

six-year experience. Eur J Trauma 2000;6:147.

12. Ertel W, Keel M, Eid K, et al. Control of severe hemorrhage

using C-clamp and pelvic packing in multiply injured

patients with pelvic ring disruption. J Orthop Trauma

2001;15:46874.

13. Finan MA, Fiorica JV, Hoffman MS, et al. Massive pelvic

hemorrhage during gynecologic cancer surgery: pack and

go back. Gynecol Oncol 1996;62:3905.

14. Flint L, Babikian G, Anders M, et al. Denitive control of

mortality from severe pelvic fracture. Ann Surg 1990;211:

7037.

15. Ganz R, Krushell R, Jakob R, et al. The antishock pelvic

clamp. Clin Orthop 1991;267:718.

16. Gansslen A, Pehlemann T, Paul C, et al. Epidemiology of

pelvic ring injuries. Injury 1996;27:S-A139.

17. Giannoudis PV. Current concepts of the inammatory

response after major trauma: an update. Injury 2003;

34(6):397404.

18. Giannoudis PV. Surgical priorities in damage control in

polytrauma. Joint Bone Joint Surg 2003;85-B:47884.

19. Grabenwoger F, Dock W, Ittner G. Perkutane Embolisation

von retroperitonealen Blutungen bei Beckenfrakturen.

RO

FO 1989;150:3358.

20. Grimm M, Vrahas M, Thomas K. Pressurevolume charac-

teristics of the intact and disrupted pelvic retroperitoneum.

J Trauma 1998;44:4549.

21. Hamill J, Holden A, Paice R, et al. Pelvic fracture pattern

predicts pelvic arterial haemorrhage. Aust N Z J Surg

2000;70:33843.

22. Holting T, Buhr H, Richter G, et al. Diagnosis and treatment

of retroperitoneal hematoma in multiple trauma patients.

Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1992;111:3236.

23. Huittinen V, Sla tis P. Postmortem angiography and dissec-

tion of the hypogastric artery in pelvic fractures. Surgery

1973;73:45462.

24. Kadish L, Stein J, Kotler S. Angiographic diagnosis and

treatment of bleeding due to pelvic trauma. J Trauma

1973;13:10836.

25. Kellam J. The role of external xation in pelvic disruptions.

Clin Orthop 1989;241:6682.

26. Kouraklis G, Spirakos S, Glinavou A. Damage control surgery:

an alternative approach for the management of critically

injured patients. Surg Today 2002;32:195202.

27. Kregor PJ, Routt Jr ML. Unstable pelvic ring disruptions in

unstable patients. Injury 1999;30:B1928.

28. Krige JE, Bornman PC, Terblanche J. Therapeutic perihe-

patic packing in complex liver trauma. Br J Surg 1992;

79:436.

29. Lindahl J, Hirvensalo E, Bostman O, et al. Failure of

reduction with an external xator in the management of

injuries of the pelvic ring. Long-term evaluation of 110

patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1999;81:95562.

30. Little JM, Fernandes A, Tait N. Liver trauma. Aust N Z J Surg

1986;56:6139.

31. Mucha Jr P, Farnell MB. Analysis of pelvic fracture manage-

ment. J Trauma 1984;24:37986.

32. Musemeche CA, Fischer RP, Cotler HB, Andrassy RJ.

Selective management of pediatric pelvic fractures: a

conservative approach. J Pediatr Surg 1987;22:53840.

33. Moore FA, Moore EE. Evolving concepts in the pathogenesis

of post-injury multiple organ failure. Surg Clin North Am

1995;75:25777.

34. Pape HC, Giannoudis PV, Krettek C. The timing of fracture

treatment in polytrauma patients: relevance of damage

control orthopaedic surgery. Am J Surg 2002;183:6229.

35. Perez JV, Hughes TM, Bowers K. Angiographic embolisation

in pelvic fracture. Injury 1998;29:18791.

36. Parreira JG, Solda S, Rasslan S. Damage control. A tactical

alternative for the management of exanguinating trauma

patients. Arq Gastroenterol 2002;39:18897.

37. Platz A, Friedl H, Kohler A, et al. Chirurgisches Management

bei schweren Beckenquetschverletzungen. Helv Chir Acta

1992;58:9259.

38. Pohlemann T, Ga nsslen A, Bosch U, et al. The technique of

packing for control of hemorrhage in complex pelvic

fractures. Tech Orthop 1995;9:26770.

39. Pohlemann T, Culemann U, Ga nsslen A, et al. Die schwere

Beckenverletzung mit pelviner Massenblutung: Ermittlung

der Blutungsschwere und klinische Erfahrung mit der

Notfallstabilisierung. Unfallchirurg 1996;99:73443.

40. Pohlemann T, Tscherne H, Baumgartel F, et al. Pelvic

fractures: epidemiology, therapy and long-term outcome.

Overview of the multicenter study of the pelvis study group.

Unfallchirurg 1996;99:1607.

41. Poka A, Libby E. Indications and techniques for external

xation of the pelvis. Clin Orthop 1996;329:549.

42. Riemer BL, Buttereld SL, Diamond DL, et al. Acute

mortality associated with injuries to the pelvic ring: the

role of early patient mobilisation and external xation. J

Trauma 1993;35:6715.

43. Riska E, von Bonsdorf H, Hakkinen S, et al. External xation

of unstable pelvic fractures. Int Orthop 1997;3:1838.

44. Rommens PM. Pelvic ring injuries: a challenge for the

trauma surgeon. Acta Chir Belg 1996;96:7884.

45. Routt M, Falicov A, Woodhouse E, et al. Circumferential

pelvic antishock sheeting: a temporary resuscitation aid. J

Orthop Trauma 2002;16:458.

46. Routt Jr ML, Nork SE, Mills WJ. High-energy pelvic ring

disruptions. Orthop Clin North Am 2002;33:5972.

47. Saueracker AJ, McCroskey BL, Moore EE, et al. Intraopera-

tive hypogastric artery embolization for life-threatening

pelvic hemorrhage: a preliminary report. J Trauma 1987;27:

11279.

48. Shapiro MB, Jenkins DH, Schwab CW, et al. Damage control:

collective review. J Trauma 2000;49:96978.

676 P.V. Giannoudis, H.C. Pape

49. Simpson T, Krieg JC, Heuer F. Stabilization of pelvic ring

disruptions with a circumferential sheet. J Trauma 2002;

52:158561.

50. Tscherne H, Pohlemann T, Gansslen A, et al. Crush injuries

of the pelvis. Eur J Surg 2001;166:27682.

51. Tucker MC, Nork SE, Simonian PT, et al. Simple anterior

pelvic external xation. J Trauma 2000;49:98994.

52. Velmahos GC, Chahwan S, Hanks SE, et al. Angiographic

embolization of bilateral internal iliac arteries to control

life-threatening hemorrhage after blunt trauma to the

pelvis. Am Surg 2000;66:85862.

53. Vermeulen B, Peter R, Hoffmeyer P, et al. Prehospital

stabilization of pelvic dislocations: a new strap belt to

provide temporary hemodynamic stabilization. Swiss Surg

1999;5:436.

54. Vrahas MS, Wilson SC, Cummings PD, et al. Comparison of

xation methods for preventing pelvic ring expansion.

Orthopedics 1998;21:2859.

55. Waydhas C, Nast-Kolb D, Trupka A, et al. Posttraumatic

inammatory response, secondary operations, and late

multiple organ failure. J Trauma 1996;40:62431.

56. Yang A, Iannacone W. External xation for pelvic ring

disruptions. Orthop Clin North Am 1997;28:33144.

57. Young JWR, Burgess AR, Brumback RJ, Poka A. Pelvic

fractures: value of plain radiography in early assessment

and management. Radiology 1986;160:44551.

Damage control orthopaedics in unstable pelvic ring injuries 677

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Finals Trans (Hema)Document16 pagesFinals Trans (Hema)Ayesha CaragNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Management of Surgical HemostasisDocument71 pagesManagement of Surgical HemostasisbogdanotiNo ratings yet

- JNC 8 Guideline Algorithm for Treating HypertensionDocument2 pagesJNC 8 Guideline Algorithm for Treating HypertensionTaradifaNurInsi0% (1)

- Percutaneous Transhepatic CholangiographyDocument3 pagesPercutaneous Transhepatic CholangiographyRonel UsitaNo ratings yet

- CircumcisionDocument6 pagesCircumcisionnursereview92% (12)

- Adult Cutaneous Fungal Infections 1 DermatophytesDocument61 pagesAdult Cutaneous Fungal Infections 1 DermatophytesAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahNo ratings yet

- Beta-Blockers in Acute Heart FailureDocument3 pagesBeta-Blockers in Acute Heart FailureAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahNo ratings yet

- Anemia en AncianosDocument8 pagesAnemia en AncianosWilliam OslerNo ratings yet

- Chapter32 - UTI in ElderyDocument4 pagesChapter32 - UTI in ElderyInes DantasNo ratings yet

- Dertmatitis AtopikDocument7 pagesDertmatitis AtopikAmanda FaradillahNo ratings yet

- High Altitude HypoxiaDocument4 pagesHigh Altitude HypoxiaAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahNo ratings yet

- Antibacterial ActivityDocument19 pagesAntibacterial ActivityAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahNo ratings yet

- Current Opinion: European Heart Journal (2017) 00, 1-14 Doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx003Document14 pagesCurrent Opinion: European Heart Journal (2017) 00, 1-14 Doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx003grace kelyNo ratings yet

- Section6 Psoriasis Guideline PDFDocument38 pagesSection6 Psoriasis Guideline PDFDesi RatnaningtyasNo ratings yet

- High Blood Pressure - ACC - AHA Releases Updated Guideline - Practice Guidelines - American Family PhysicianDocument2 pagesHigh Blood Pressure - ACC - AHA Releases Updated Guideline - Practice Guidelines - American Family PhysicianAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahNo ratings yet

- Apoptosis - A Biological PhenomenonDocument13 pagesApoptosis - A Biological PhenomenonAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahNo ratings yet

- Apoptosis - A Biological PhenomenonDocument13 pagesApoptosis - A Biological PhenomenonAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahNo ratings yet

- Apoptosis Shaping of Embryo PDFDocument10 pagesApoptosis Shaping of Embryo PDFAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahNo ratings yet

- STD Treatment 2015Document140 pagesSTD Treatment 2015Supalerk KowinthanaphatNo ratings yet

- Main Article - BM PancytopeniaDocument10 pagesMain Article - BM PancytopeniaAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahNo ratings yet

- The Essentials of Contraceptive TechnologyDocument355 pagesThe Essentials of Contraceptive TechnologyIndah PurnamasariNo ratings yet

- Ireland Vaccination Guideline For GP 2018Document56 pagesIreland Vaccination Guideline For GP 2018Abdur Rachman Ba'abdullahNo ratings yet

- Pulmonary AbscessDocument5 pagesPulmonary AbscessAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahNo ratings yet

- Hypersensitivities Dermatitis Atopic PDFDocument70 pagesHypersensitivities Dermatitis Atopic PDFSarahUtamiSr.No ratings yet

- Jurnal Kulit 2Document14 pagesJurnal Kulit 2UmmulAklaNo ratings yet

- Ireland Vaccination Guideline For GP 2018Document56 pagesIreland Vaccination Guideline For GP 2018Abdur Rachman Ba'abdullahNo ratings yet

- STD Treatment 2015Document140 pagesSTD Treatment 2015Supalerk KowinthanaphatNo ratings yet

- En V29n3a01Document2 pagesEn V29n3a01Abdur Rachman Ba'abdullahNo ratings yet

- Pulmonary AbscessDocument5 pagesPulmonary AbscessAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahNo ratings yet

- Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Inducedby Hydroxychloroquine PDFDocument3 pagesAcute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Inducedby Hydroxychloroquine PDFAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahNo ratings yet

- Section6 Psoriasis Guideline PDFDocument38 pagesSection6 Psoriasis Guideline PDFDesi RatnaningtyasNo ratings yet

- Postgrad Med J 2004 Mathew 196 200Document6 pagesPostgrad Med J 2004 Mathew 196 200Abdur Rachman Ba'abdullahNo ratings yet

- Global Initiative For Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseDocument139 pagesGlobal Initiative For Chronic Obstructive Lung Diseaseport spyNo ratings yet

- Ulcus Decubitus PDFDocument9 pagesUlcus Decubitus PDFIrvan FathurohmanNo ratings yet

- Soft Tissue InjuryDocument3 pagesSoft Tissue InjuryLawrence Cada NofiesNo ratings yet

- Causes, Symptoms and Treatments of Iron Deficiency AnemiaDocument85 pagesCauses, Symptoms and Treatments of Iron Deficiency AnemiafrendirachmadNo ratings yet

- 31 Coagulation Disorders in PregnancyDocument12 pages31 Coagulation Disorders in PregnancyParvathy R NairNo ratings yet

- Subjective: Goals: - : Nursing Care Plan Assessment Diagnosis Planning Intervention Rationale EvaluationDocument18 pagesSubjective: Goals: - : Nursing Care Plan Assessment Diagnosis Planning Intervention Rationale EvaluationJennalyn Padua SevillaNo ratings yet

- Pharm Stroke: Care PadaDocument38 pagesPharm Stroke: Care PadaDimas RfNo ratings yet

- Service Learning Proposal Kbaldwin Nurs 450Document6 pagesService Learning Proposal Kbaldwin Nurs 450api-239640492No ratings yet

- Review Inherited Platelet Disorders - Thrombocytopenias and ThrombocytopathiesDocument15 pagesReview Inherited Platelet Disorders - Thrombocytopenias and ThrombocytopathieskaynabilNo ratings yet

- Tugas TutorDocument6 pagesTugas TutorKinanti Lingga PutiNo ratings yet

- Dahi̇li̇ye'Detus Sorulari EngDocument83 pagesDahi̇li̇ye'Detus Sorulari EngKhalid ShafiqNo ratings yet

- Black Sea, Dark NightDocument18 pagesBlack Sea, Dark NightYusop B. MasdalNo ratings yet

- ES V 0281 001 FinalSPCDocument4 pagesES V 0281 001 FinalSPCPankaj BeniwalNo ratings yet

- Bleeding DisordersDocument92 pagesBleeding DisordersIsaac MwangiNo ratings yet

- Massive Blood Traansfusion MazenDocument8 pagesMassive Blood Traansfusion MazenOsama BakheetNo ratings yet

- Massive Haemorrhage: P Donnelly B FergusonDocument18 pagesMassive Haemorrhage: P Donnelly B FergusonRizqiNo ratings yet

- Blood Donation Research Paper - LatestDocument10 pagesBlood Donation Research Paper - LatestEileen1113100% (2)

- Shalya Paper-I PDFDocument17 pagesShalya Paper-I PDFSusmita VinupamulaNo ratings yet

- What Is Hypovolemic ShockDocument4 pagesWhat Is Hypovolemic ShockDukittyNo ratings yet

- Aerie 14th Edition Manual PDF FinalDocument128 pagesAerie 14th Edition Manual PDF FinalAina P. T.No ratings yet

- Access To Special Care Dentistry, Part 5. Safety: A. Dougall and J. FiskeDocument14 pagesAccess To Special Care Dentistry, Part 5. Safety: A. Dougall and J. FiskeMostafa FayadNo ratings yet

- Estimation of Obstetric Blood LossDocument6 pagesEstimation of Obstetric Blood LossFaradilla ElmiNo ratings yet

- Ovariectomy Via Colpotomy ApproachDocument5 pagesOvariectomy Via Colpotomy ApproachMeredithWindhorseHudes-Lowder100% (1)

- RRT Care Plan Protocol GuideDocument4 pagesRRT Care Plan Protocol GuideTahani KhalilNo ratings yet

- LovenoxDocument1 pageLovenoxAdrianne BazoNo ratings yet

- Stop the Bleed Training Improves Rescuer Skills and ConfidenceDocument7 pagesStop the Bleed Training Improves Rescuer Skills and Confidencejapra17No ratings yet

- 11 Nursing Care PlansDocument4 pages11 Nursing Care Planseknok03No ratings yet

- Postpartum HemorrhageDocument5 pagesPostpartum Hemorrhageapi-354418387No ratings yet