Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Discourse Analysis

Uploaded by

Lauren Cecilia Holiday BuysCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Discourse Analysis

Uploaded by

Lauren Cecilia Holiday BuysCopyright:

Available Formats

Holiday 1 Lauren Holiday ENC 4275 Dr.

Hall 27 November 2013 Emergent Expertise: Adaptability in the Tutoring Session Introduction Number 18 in our University Writing Centers list of 20 Valued Practices for Tutoring Writing suggests that tutors be co-learner[s] and rhetorical/cultural informant[s], and that we are to avoid roles of editor and authority. We read pieces, like Richard Leahys What the College Writing Center Isand Isnt, that also make claims about the roles tutors must take on during a session: listener, teacher, coach, counselor, fellow writer, editor, and critic (43). And then we look at models for tutoring, such as Teresa Hennings Tutoring Style Decision Tree, that help us navigate directive, non-directive, and collaborative techniques, and hierarchical, dialogic, and co-reader postures (6). Yet, reading, discussing, and understanding all of this writing center theory and research is only half of the tutoring equation; tutors must also effectively put this knowledge into practice. Before I started the conversation analysis of my recorded session, I believed my ability to navigate these roles, techniques, and postures quite effective. Yet, when I studied my transcript, I found that some of my practices were not living up to the values I gained through reading this theory and research. The discourse manipulations I used to hold the floor, the corrections and advice I gave, the praise I offered, and the style of questions I employed all show how I

Holiday 2 dominated the session with my expert role, leaving my flexibility at the UWC entrance. As unfortunate as these repeated patterns of control are, the session was not a complete disaster. Signs of joint products and cooperative overlaps, active listening, collaboration and learning, and laughter were demonstrated in this session as well. I would like to discuss all of these moves in more depth to make an argument for a malleable approach to the expert role. Emergent Expertise: A Quick Discussion It is true that tutors are experts in writing conventions; otherwise they would not be employed by writing centers. So, denying the obvious fact that, during a tutoring session, tutors have a position of authority when it comes to writing would be quite ignorant. It would also be unfortunate to assume the expert role is inherently detrimental to learning, and tutors should therefore avoid taking up such a directive role while tutoring. Neither of these fallacies are being argued for in this paper. Rather, a look at how expertise is meant to be flexiblenot held or controlled by one person in authority, but instead cultivated through the transaction and conversation of peerswill be discussed through an analysis of discourse. This malleable approach to the expert role is described as emergent expertise, and helps us to elevate students positions in teaching and learning and potentially leads us to achieve an equitable, studentcentered, and empowered education (Hsu and Roth 4). The Down-Sides to the Expert Role 1. Discourse Manipulations Word Count, Backchannelling

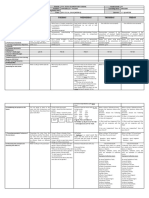

Holiday 3 During this session I (L) dominated the word count by 61 percent, leaving my tutee (S) with only 839 words in the seventeen minutes I transcribed. One specific page of the transcription was particularly upsetting; I spoke 355 words and my tutee only 66. In these 47 lines I was giving advice on switching the concluding paragraph to be the introduction of her history paper. You can see in the excerpt below that my advice is received with backchannelling from my tutee (highlighted in grey), what Laurel Black describes as, agreement or support either latched onto [the tutors] utterance or positioned during normal pauses (49).

This backchannelling indicates that my tutee most likely already knew how an introduction and conclusion function in an essay. But because I was in expert-mode, I failed to realize that a lecture on the subject was a waste of our session time. My writer was simply encouraging me to finish my monologue quickly, not necessarily acknowledging or affirming the correctness of [my] summary (Black 45). Through the lens of emergent expertise we can see in this example that the role of expert seems not so expert and the role of novice seems not so nave (Hsu and Roth 8). It is obvious here that my scaffolding, provid[ing] resources that allow [my tutee] to engage in a practice at a level higher than unaided performance, is not actually helping my

Holiday 4 writer achieve anything normally beyond her reach (Hsu and Roth 3). These scaffolds simply function as a way for me to prove my expertise in an area that I feel comfortable dominating. Place Holders, Competitive Overlaps Throughout this session, the use of place holders, or what Magdelena Gilewicz and Terese Thonus call filled pauses, frequently allowed me to maintain the floor, or main channel of conversation, again flaunting my expert status (31). I did this in two ways: using the words uhm and okay, and stringing out the vowels in certain words.

You can see in line 48 that my place holder uhm does its job of maintaining the floor (to prevent interruptions and overlaps) or formulating a response, so well that my writer offers no topic or backchannel for [5] seconds (a long pause in talk!) (Gilewicz and Thonus 31; Black 45). I use another discourse marker, the competitive overlap, to dominate the conversation by interrupting my writer before she has finished speaking, even when I acknowledge that my overlap is rude.

Holiday 5 Place holders and competitive overlaps function in my session in ways that show I have the higher status. By holding my place in the conversation and only allowing my writer to talk when I allow, I show that my words are more important than my tutees words. If Herbert A. Simon was right in saying that Learning results from what the student does and thinks and only from what the student does and thinks, than my speech techniques are only effective in inhibiting my tutee from learning (qtd. in Ambrose et al. 1). This is not the dynamic process that emerges from [tutor-tutee] transactions that emergent expertise would have brought out (Hsu and Roth 21). Instead, my expert role is getting in the way of my writer, cutting her off in a way that is only beneficial to maintaining my supposed high status. 2. Expert Advice Thesis in Conclusion An important move that I make in this session is Offer[ing] specific, useful suggestions for revisions, one of the UWCs valued practices. But I do this in a way that relies heavily on the tutee seeing me as an expert on whatever advice I am giving out. Unfortunately, these corrections are less than ideal because I am, in fact, pretending expertise. In this first example I prove Leahy wrong when he states that, [tutors] learn to avoid the role of little teachers (44).

Using the words I think puts me in a place to hand out pieces of writing consultant advice justified solely by my perceived position of authority, not through research or common practice.

Holiday 6 Not only is my advice pulled out of thin air, but it is also completely and utterly wrong. Fortunately, it seems as if my tutee knows this lecture has no value; she uses backchannelling (mhm, okay, yeah) to again quicken my speech toward an end. My use of advice proves that I am in the mindset of expertise as a property of individuals, relying heavily on my alleged credibility as a writing center tutor (Hsu and Roth 1). Plural or Past-Tense? In this second example of expert advice I throw out the tenth valued practice, Avoid a scattershot approach, by fixing every error that I notice when we read the paper aloud.

Obviously, my statement that she must change was to is because it follows a singular noun is untrue. But even if my correction did make sense, the way I approach teaching my tutee this grammar lesson shows that I value control and authority. I am the Storehouse of knowledge, dispensing information at my whim with no regards to my writers questions or concerns (Lunsford 4). I am product-centered, not process-centered (Leahy 47). Instead, I could have modeled the picture Leahy paints of tutor-tutee interaction: [tutors] must simultaneously be involved in [the writing] process with the writer and stand outside of it, to monitor how it is going and to allow the writer to make the decisions (47). 3. Praise

Holiday 7 Praisequalified or notis an evaluation strategy; there is a clear right and wrong way to do something, and what the tutor praises is the right. When is it appropriate to show such a strong authority position? Can praise have a negative effect on the tutoring session, the writer, or even the paper? From what I have seen in my transcript, the answer to these questions depends on how the tutor is using the praiseas a way to manipulate the conversation and isolate the writer, or truly giving appreciation for making a step in the learning process. The latter is seen once in my transcript:

You can see that after I previously pointed out a punctuation mistake, my writer catches the next one with a simple prompt of okay. I then made it a point to show that she was the one who proofread and caught the error. Regrettably, the former is also noted here:

My praise in this instance controls the topic; I dismiss even the chance of looking at APA format. I also force a them vs. us mentality, in that I align her and I against all other writers that need help with APA format. This signals to my writer that in future concerns, she should be on my level or else be deemed an other. I force her to take my advice no matter what because I have a secret that keeps me above them.

Holiday 8 A third example of how I use praise shows that my expertise can be confusing when I follow praise with a revision suggestion. In the instance below I read a part of her essay, stating, this is great how it is, and then give advice to maybe try to introduce that a little more.

My praise is acting as a way to soften the blow of my recommendation for change, not genuinely acknowledging something done well or learning shown. While hiding my criticism inside praise makes our relationship less confrontational, it does nothing to model the problem-solving or collaboration that emergent expertise calls for. It actually makes my advice unclear: why would I praise something that I later suggest should be changed? These mixed signals could potentially put my writer into an state of skepticism, blocking our session from achieving true learning. 4. Questions Forced Agreement Even my questions prove isolating to the writer, as I consistently challenge her understanding of my revisions by asking, Does that make sense?

Holiday 9 This question is actually asking, Do you want to challenge the expert advice I so graciously gave you? If she were to answer that, in fact, she did not understand, she risks placing herself in that other group of some people [who] have trouble with that (line 25). I also quiz her with a never ending barrage of inquiries starting with Do you think?

These questions all end in the way I would revise the paper: this is a better point to put after you discuss Bacons Rebellion than before, turn this into your conclusion and make this your introduction, and that is an okay way to start your paper. I am simply disguising them as genuine inquiries into what she believes is best for her paper. This is a deceptive, albeit unconscious, way of asserting my corrections and positioning them in a way that cannot be challenged. Black would consider this move forced agreement, a way to force [tutees] into a cognitive relationship they find difficult to resist (65). Like I noted how asking questions in such a closed ended format hinders the responses my writer could give, Black finds the same consequences in forced agreement, saying, If the penalties are too great for challenging that shared knowledge and the options for other responses are slender, then [tutors] shape by force (47). If, instead, my question was more of a prompt, or an imperative, my tutee could have

Holiday 10 been at the center of understanding (Johnson 34). Simply switching the wording to Tell me what sense that makes to you, could have made the difference in actually showing that my writer was learning. (A discussion on the use of imperatives can be found in the section titled 3. Collaboration and Learning on page thirteen.) Minimal Responses The previously mentioned type of question elicits only minimal responses, [short] continuers that fill turn slots, not the more valued longer explanations that imperatives bring out, as stated above (Gilewicz and Thonus 35; Johnson 34). Here is a look at minimal responses (highlighted in grey):

In this portion of the consultation I am trying to learn assignment requirements or rhetorical situation, including the writers understanding, our second valued practice. Unfortunately, the way I control what portions of the rubric get discussed obstructs my tutee from explaining what she understands or needs help problem-solving. This is because I read the guidelines aloud and then asked obvious questions (indicated in bold) that only require short, meaningless answers.

Holiday 11 This method gives no indication to whether or not my writer actually comprehends all the assignment requires, it simply shuts her up long enough for me to put forth my own expert tutor understanding. Aiding in my twisted technique of controlling, close-ended questions is the word so (underlined above), which I use with conclusive force, as if agreement has been met, again tying back into the use of forced agreement (Black 69). The Flexible Expert 1. Joint Products and Cooperative Overlaps Gilewicz and Thonus describe a particular type of overlap called joint products that happen when speakers complete each others utterances (36). Below are four examples from my transcript with the joint products highlighted in grey.

Finishing each others thoughts in this way represent[s] a movement toward greater solidarity and collaboration, one of the main focuses in a Burkean Parlor style writing center such as ours (Gilewicz and Thonus 36; Lunsford 7). This is because we value knowledge as contextually bound, as always socially constructed, which is done mainly through conversation (Lunsford 8). These statement completions indicate to me a step toward placing control, power, and authority

Holiday 12 not in the tutor or staff, not in the individual student, but in the negotiating group, the true tutor and tutee speech dynamic (Lunsford 8). Black would call these joint products, cooperative overlaps, and in doing so she focuses on a different aspect of this discourse marker. She believes it indicate[s] not only the strict attention [the writer is] paying to the [tutor] but [her] willingness to assist the [tutor] in continuing to speak, which registers as support and encouragement to the tutor (64). She never mentions if this phenomenon goes the other waytutor to tuteebut I seemed to complete more of my tutees phrases than she did of mine. This is a step away from the expert role and into the listener and co-learner position of emergent expertise that I am arguing for. 2. Active Listening Another form of Blacks cooperative overlap is achieved through active listening, a structured form of listening and responding that focuses the attention on the speaker (Active Listening).

In this example I pay careful attention to the concerns of my writer and then repeat them back to her, in her same language, to check if I understood her correctly (Active Listening). Instead of asking questions that put my tutee on the spot and make her repeat herself, this technique shows

Holiday 13 that I care enough to listen closely and want to comprehend her reasons for coming to the writing center. Active listening is especially important for the beginning of the consultation, because many decisions and impressions are made during these first five to ten minutes. Stepping down from our position of authority is crucial to doing active listening effectively. It is only when we see learning as a dynamic process that emerges from [tutor-tutee] transactions, where participants may take both roles [of expert and novice] not only in turn but also simultaneously, that true emergent expertise through collaboration can occur (Hsu and Roth 21). 3. Collaboration and Learning One way to accomplish learning in a session comes about through the tutor making declarative statements, especially paraphrases, and using imperative sentences [that] often invites longer, more reflective responses (Johnson 34). Closely tied to active listening, stating questions as demands allows the tutee to control the direction of the inquiry, and also helps foster a questioning attitude (Johnson 35). Unfortunately, in my transcript there was only one instance where I use this technique of questioning (the bolded sentence), and I use it only after my attempts at normal questioning fails (the first highlighted sentence).

Holiday 14 It is pretty clear that the response my first questions receive does nothing to force the student to consider deep structures, highlighting the success or failure of various sections of a written piece (Johnson 39). In fact, my questions make her doubt what she has written, because why would the expert tutor ask about a part of an essay unless there was something wrong with it? In contrast, my declaration of, Im stupid. So its not you, its me. So explain it to me, puts the blame on my lack of knowledge, relying on the writer as the expert of her own writing. And it is clear what a much longer, deeper, and more meaningful explanation she gave me after I admitted ignorance. This is true collaboration; a give and take of knowledge fostered by the valuing of diversity through conversation and problem-solving (Lunsford 9). 4. Laughter Us[ing] tone and body language to facilitate learning is one of our valued practices that I noticed most frequently throughout the transcription. It is also a good example of creating an atmosphere that is most conducive to collaboration; putting the tutee at ease can make her comfortable enough to share her ideas, thus allowing the tutor to generate problem-solving more effectively. This affective dimension of the consultation can be summed up here in the use of laughter during the session.

Holiday 15 Rebecca Day Babcock synthesizes findings on how laughter works in tutoring sessions by stating, Laughter can lighten the atmosphere (Ritter, 2002), establish solidarity (Haas, 1986) and enhance the tutor-tutee relationship by diffusing awkwardness (Boudreax, 1998) (55). In my five examples above, laughter is used in the same ways, mainly the last technique. Paired with eye contact, an accepting tone, and friendly body language, laughter, at appropriate times, can boost the morale in a consultation and create a welcoming, collaborative environment, one based on internship (apprentice-like) learning through emergent expertise (Hsu and Roth 3). Conclusion With emergent expertise as the center focus of the tutoring session, tutees are not just deemed as receivers but as crucial contributors who could make their learning (and teaching) more efficient and successful (Hsu and Roth 22). Yet, this ideology hinges on rethink[ing] the presupposition of the institutional roles of experts and novices in the learning process (Hsu and Roth 21). Instead of manipulating the discourse through word count, place holders, and competitive overlaps, a tutor should sit back and actively listen, using joint products and cooperative overlaps to show the tutee she cares by being an empathetic respondent (McAndrew and Reigstad 18). Framing advice and corrections in a way that produces genuine conversations about writing practices is better than being overly critical and nitpicking about [the] writers work (McAndrew and Reigstad 17). We must also avoid empty flattery and over generalized praise, instead focusing on being a dumb reader, one who is not an authority in the subject matter (McAndrew and Reigstad 20). And we should laugh. Have fun collaborating, building community, doing the thing, because, the real expert about the writing is the writer, not the tutor (McAndrew and Reigstad 20).

Holiday 16 Works Cited 20 Value Practices for Tutoring Writing. UCFs University Writing Center. 2013. Print. Active Listening. Conflict Research Consortium, University of Colorado. 1998. Web. 13 November 2013. Ambrose, Susan A., et al. How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2010. Print. Babcock, Rebecca Day, et al. A Synthesis of Qualitative Studies of Writing Center Tutoring, 1983-2006. New York: Peter Lang, 2012. Print. Black, Laurel. Between Talk and Teaching: Reconsidering the Writing Conference. Logan: Utah State University Press, (1998). Print. Gilewicz, Magdalena, and Terese Thonus. Close Vertical Transcription in Writing Center Training and Research. The Writing Center Journal. 24.1 (2003). 25-49. Print. Henning, Teresa. The Tutoring Style Decision Tree: A Useful Heuristic for Tutors. The Writing Lab Newsletter. 30.1 (2005). 5-7. Print. Hsu, Pei-Ling, and Wolff-Michael Roth. Lab Technicians and High School Student Interns Who Is Scaffolding Whom?: On Forms of Emergent Expertise. Science Education. 93.1 (2008): 1-25. Wiley InterScience. Web. 26 November 2013. Johnson, JoAnn. Reevaluation of the Question as a Teaching Tool. Dynamics of the Writing Conference: Social and Cognitive Interaction. Eds. Thomas Flynn and Mary King. Urbana: NCTE, 1993. 34-39. Print.

Holiday 17 Leahy, Richard. What the College Writing Center Isand Isnt. College Teaching. 38.2 (1990): 43-48. Print. Lunsford, Andrea. Collaboration, Control, and the Idea of the Writing Center. The Writing Center Journal 12.1 (1991): 3-10. Print. McAndrew, Donald A. and Thomas J. Reigstad. Tutoring Writing: A Practical Guide for Conferences. Portsmouth: Boynton/Cook Publishers, Inc., 2001. Print.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Ya'qūb Ibn Is Āq Al-Kindī, Alfred L. Ivry-Al-Kindi's Metaphysics - A Translation of Ya'qūb Ibn Is Āq Al-Kindī's Treatise On First Philosophy (Fī Al-Falsafah Al-Ūlā) - SUNY (1974) PDFDocument215 pagesYa'qūb Ibn Is Āq Al-Kindī, Alfred L. Ivry-Al-Kindi's Metaphysics - A Translation of Ya'qūb Ibn Is Āq Al-Kindī's Treatise On First Philosophy (Fī Al-Falsafah Al-Ūlā) - SUNY (1974) PDFDwi Afrianti50% (2)

- The Philippine Professional Standards For School Heads (PPSSH) IndicatorsDocument11 pagesThe Philippine Professional Standards For School Heads (PPSSH) Indicatorsjahasiel capulongNo ratings yet

- Fs JosephsonDocument393 pagesFs JosephsonZhanna Grechkosey100% (4)

- Current Assessment Trends in Malaysia Week 10Document13 pagesCurrent Assessment Trends in Malaysia Week 10Gan Zi XiNo ratings yet

- Final Score Card For MBA Jadcherla (Hyderabad) Program - 2021Document3 pagesFinal Score Card For MBA Jadcherla (Hyderabad) Program - 2021Jahnvi KanwarNo ratings yet

- NQESH Domain 3 With Answer KeyDocument8 pagesNQESH Domain 3 With Answer Keyrene cona100% (1)

- Resume Fall 2014Document1 pageResume Fall 2014Lauren Cecilia Holiday BuysNo ratings yet

- Lauren Holiday: EmploymentDocument1 pageLauren Holiday: EmploymentLauren Cecilia Holiday BuysNo ratings yet

- WUCF's ONE Media KitDocument13 pagesWUCF's ONE Media KitLauren Cecilia Holiday BuysNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical CitizenshipDocument11 pagesRhetorical CitizenshipLauren Cecilia Holiday Buys100% (1)

- Educational Scenario of Kupwara by Naseem NazirDocument8 pagesEducational Scenario of Kupwara by Naseem NazirLonenaseem NazirNo ratings yet

- Answer Key - Grade 1 Q1 WK 1Document2 pagesAnswer Key - Grade 1 Q1 WK 1APRIL VISIA SITIERNo ratings yet

- DLL - English 4 - Q1 - W8Document6 pagesDLL - English 4 - Q1 - W8Rhadbhel PulidoNo ratings yet

- Future TensesDocument3 pagesFuture TensesAndrea Figueiredo CâmaraNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Video Games On The ChildrenDocument2 pagesThe Influence of Video Games On The ChildrenCristina RataNo ratings yet

- Singaplural 2016 Festival MapDocument2 pagesSingaplural 2016 Festival MapHuyNo ratings yet

- Mass MediaDocument17 pagesMass MediaSushenSisonNo ratings yet

- Griffith Application Form UgpgDocument2 pagesGriffith Application Form UgpgDenise SummerNo ratings yet

- Test ASDocument3 pagesTest ASAgrin Febrian PradanaNo ratings yet

- Registration As An Apec ArchitectDocument6 pagesRegistration As An Apec ArchitectTonyDingleNo ratings yet

- The Saudi Executive Regulations of Professional Classification and Registration AimsDocument8 pagesThe Saudi Executive Regulations of Professional Classification and Registration AimsAliNo ratings yet

- CDC Model 6 To 8Document16 pagesCDC Model 6 To 8Mahendra SahaniNo ratings yet

- MTB - Mle Lesson Plan November 6, 2023Document3 pagesMTB - Mle Lesson Plan November 6, 2023sherry ann corderoNo ratings yet

- Display ImageDocument2 pagesDisplay Imagerakeshsharmma2001No ratings yet

- Tutorial Letter FMM3701-2022-S2Document11 pagesTutorial Letter FMM3701-2022-S2leleNo ratings yet

- BCA Full DetailsDocument3 pagesBCA Full DetailsAnkit MishraNo ratings yet

- Social Studies 10-1 Course OutlineDocument4 pagesSocial Studies 10-1 Course Outlineapi-189472135No ratings yet

- Esm2e Chapter 14 171939Document47 pagesEsm2e Chapter 14 171939Jean HoNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan For DemoDocument11 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan For DemoCheng ChengNo ratings yet

- Michigan School Funding: Crisis and OpportunityDocument52 pagesMichigan School Funding: Crisis and OpportunityThe Education Trust MidwestNo ratings yet

- Gaining Support For A Project: Chapter FiveDocument9 pagesGaining Support For A Project: Chapter FiveJavier Pagan TorresNo ratings yet

- San Antonio de Padua College Foundation of Pila, Laguna IncDocument3 pagesSan Antonio de Padua College Foundation of Pila, Laguna IncTobias LowrenceNo ratings yet

- Math ThesisDocument14 pagesMath ThesisElreen AyaNo ratings yet

- Shs Class RecordDocument62 pagesShs Class RecordMae Sheilou Conserva PateroNo ratings yet