Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Adorno Esteika Pomirenja: Necessary Relation To The Understanding (A 119) - Appearances, He Says

Uploaded by

andrejkirilenkoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Adorno Esteika Pomirenja: Necessary Relation To The Understanding (A 119) - Appearances, He Says

Uploaded by

andrejkirilenkoCopyright:

Available Formats

adorno esteika pomirenja

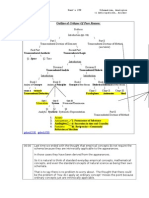

Therefore, the character of all great art is that of darkness, joylessness, and dissonance. These istinska individualnost spasenje subjekta same. The categories are concepts of an object in general (B 129); they are a priori conditions of the possibility of experience (A 94, B 126). We are able to experience objects, that is, only because we have the concept of an object. We do not derive this concept from experience, for we could not experience anything as an object without already having the general concept of an object. These concepts do not arise from experience; they underlie the possibility of experience. Kant is driving toward the conclusion that appearances have a necessary relation to the understanding (A 119). Appearances, he says, are data for a possible experience; they therefore have to relate to the understanding. The transcendental unity of apperception is responsible for what Kant calls the affinity of our representationthat is, their being our representations, their constituting a single empirical consciousnessand also the rule-governed character of the synthesis of the manifold of intuition. If that synthesis were not rule-governed, the combination of the data of sense would not yield knowledge but random and accidental collocations (A 121) such as the products of imagination in the usual sense. We may freely combine concepts, to form the notion of a threeheaded dragon or a golden mountain, but we gain no knowledge of what is actual from exercising that freedom. We attain knowledge of objects because the construction of objects actually presented in experience is rulegoverned. rules. The objective deduction, Kant maintains, shows that we can know objects because we construct them: Thus the order and regu larity in the appearances, which we entitle nature, we ourselves introduce. We could never find them in appearances, had not we ourselves, or the nature of our mind, originally set them there (A 125). The understanding, consequently, is nothing less than the lawgiver of nature (A 126). This follows from Kants argument, for it has shown that the transcendental unity is an objective condition of all knowledge. It is not merely a condition that I myself require in knowing an object, but is a condition under which every intuition must stand in order to become an object for me (B 138). Certainly, he means to show that the hope of extending knowledge beyond the realm of sense experience is illusory. But he uses the term illusion in a more specific sense: an illusion may be said to consist in treating the subjective condition of thinking as being knowledge of the object (A 396; see A 297, B 3534). The key to the Analytic is the Copernican revolution, the idea that the faculty of thinking constitutes objects. This should not tempt us to conclude, however, that subjectivity and objectivitythinking and knowingmatch effortlessly. Clearly we may think of things that are not objectively real through imagination. We may also make mistakes. Most seriously, our thinking extends easily beyond the realm of sense experience. We may engage in metaphysical contemplation, arguing about the freedom of the will, the existence of God, and the mortality or immortality of the soul. But Kant denies that we can attain any real

knowledge of these matters.

As with the self, so with things-in-themselves. The second consequence of Kants distinction is thus that knowledge of things -in-them-selves is impossible; knowledge is limited to the sphere of experience. The limits of knowledge become clear in thinking about the role of the categories. The pure concepts of the understanding are conditions of the possibility of experience. They have a priori validity, against the claims of the skeptic, because all empirical knowledge of objects would necessarily conform to such concepts, because only as thus presupposing them is anything possible as an object of experience (A 93, B 126). Objects of experience must conform to the categories. Objects beyond the realm of experience, however, face no such constraint. In fact, we have no reason to believe that the categories apply to them at all. The categories conform to objects of possible experience because we synthesize those objects from the data of sensibility. What lies beyond sensibility lies beyond the categories, for we have no reason to believe that it results from such a process of synthesis. svo mogue znanje je subjektivno znanje

U korenu Benjaminove filozofije lei kritika i nadogradnja Kantovog koncepta transcendentalnog iskustva izvedena kroz koncept spekulativnog iskustva. Subjekt je kod Kanta stavljen u centar filozofskog sistema, kao posednik univerzalnih a priornih formi saznanja, kategorija, koji konstituiu logikim zakonima sinteze objekte kao pojave. Kant razdvaja domen subjektivno mogueg iskustva, fenomenalnu sferu, od domena stvari po sebi kao noumenalne sfere metafizike i apsoluta. Opseg subjektivnog iskustva je tako sveden na odnos aktivnog subjekta i pasivnog objekta, gde je percepcija objekta uslovljena univerzalnim, fiksnim kognitivnim kategorijama razuma, koji organizuju prostornovremenskim formu opaanja objekata. Iskustvo je tako redukovano ovim univerzalnim kategorijama logike, koje postoje nezavisno od objekata u sferi transcendatalnosti koja kao podloga odreuje okvir mogueg iskustva. Sfera stvari po sebi i apsoluta je prema Kantu van kognitivnih mogunosti subjekta i ne postoji mogunost njenog saznanja.1 Benjaminov koncept spekulativnog iskustva ima za cilj da premosti jaz izmeu ova dva domena i da pokua da definie nain na koji je apsolutno sadrano u fenomenalnom.

Imanuel Kant, Kritika istog uma, BIGZ, Beograd, 1976.

You might also like

- Feldman, Richard - 2003 - Epistemology PrenticeHallDocument103 pagesFeldman, Richard - 2003 - Epistemology PrenticeHallÁngel Luna100% (7)

- Solution Manual 3eDocument41 pagesSolution Manual 3ejaijohnk67% (3)

- Badiou, Alain Zizek, Slavoj - Philosophy in The Present (2009) PDFDocument70 pagesBadiou, Alain Zizek, Slavoj - Philosophy in The Present (2009) PDFGonzalo Morán Gutiérrez100% (9)

- True Humans KaNtDocument10 pagesTrue Humans KaNtNicodeo Vicente IgnacioNo ratings yet

- Nelson Goodman - Problems and Projects-Bobbs-Merrill (1972)Document236 pagesNelson Goodman - Problems and Projects-Bobbs-Merrill (1972)Fábbio Cerezoli100% (2)

- Skinner, B. F. (1945) - The Operational Analysis of Psychological Terms PDFDocument8 pagesSkinner, B. F. (1945) - The Operational Analysis of Psychological Terms PDFJota S. FernandesNo ratings yet

- The Authenticity of The Thing-In-Itself: Kant, Brentano, and HeideggerDocument12 pagesThe Authenticity of The Thing-In-Itself: Kant, Brentano, and HeideggerFranklin Tyler FehrmanNo ratings yet

- The Transcendental Deduction Explained To Five Year Olds (Not Really)Document5 pagesThe Transcendental Deduction Explained To Five Year Olds (Not Really)Stefanos TraanNo ratings yet

- Lectures On Kant S Critique of Pure Reason 2014Document166 pagesLectures On Kant S Critique of Pure Reason 2014Mehdi FaizyNo ratings yet

- CPR Kant (1) - 101-130Document30 pagesCPR Kant (1) - 101-130Lidra Ety Syahfitri Harahap lidraety.2022No ratings yet

- Noumenon (Disambiguation)Document26 pagesNoumenon (Disambiguation)ReadBooks OnlineNo ratings yet

- Phenomena and NoumenaDocument3 pagesPhenomena and NoumenaAlejandro ToledoNo ratings yet

- Schulting (2020) - Apperception, Objectivity, and IdealismDocument10 pagesSchulting (2020) - Apperception, Objectivity, and IdealismAnonymous pZ2FXUycNo ratings yet

- Curs MetafilosofieDocument28 pagesCurs MetafilosofieIulia CebotariNo ratings yet

- Kant As NihilistDocument8 pagesKant As NihilistIsaac Hughes Green100% (1)

- Expreesionist Ontology2Document12 pagesExpreesionist Ontology2cdesob1No ratings yet

- 1984 - Lear and Stroud - The Disappearing WeDocument41 pages1984 - Lear and Stroud - The Disappearing WedomlashNo ratings yet

- CPR Kant (1) - 46-76Document31 pagesCPR Kant (1) - 46-76Lidra Ety Syahfitri Harahap lidraety.2022No ratings yet

- SocratesDocument2 pagesSocratesJorg MeurkesNo ratings yet

- Meurkes, Jorg - Longunesse, Kant and The Capacity To Judge - First ImpressionsDocument4 pagesMeurkes, Jorg - Longunesse, Kant and The Capacity To Judge - First ImpressionsjorgisdenaamNo ratings yet

- Space and Geometry in The B DeductionDocument31 pagesSpace and Geometry in The B DeductionOscar Eduardo Ocampo OrtizNo ratings yet

- Kante Theory of KnowledgeDocument13 pagesKante Theory of KnowledgeIddi KassiNo ratings yet

- Burnham Kant GlossaryDocument5 pagesBurnham Kant GlossarynachothefreeloaderNo ratings yet

- Acerp2017 34442Document14 pagesAcerp2017 34442Aryan PuriNo ratings yet

- The Mere, But Empirically Determined, Consciousness of My Own Existence Proves The Existence of Objects in Space Outside of MeDocument5 pagesThe Mere, But Empirically Determined, Consciousness of My Own Existence Proves The Existence of Objects in Space Outside of MeAlejandro ToledoNo ratings yet

- Illusions of Imagination and Adventures of Reason in Kant's First CritiqueDocument35 pagesIllusions of Imagination and Adventures of Reason in Kant's First CritiqueEdmundo68No ratings yet

- Kant: Experience and Reality Analogies of ExperienceDocument4 pagesKant: Experience and Reality Analogies of ExperienceGag PafNo ratings yet

- The Kantian Sine Qua NonDocument23 pagesThe Kantian Sine Qua NonC.J. SentellNo ratings yet

- What Has Transcendental Deduction Proven?: Andrea FaggionDocument6 pagesWhat Has Transcendental Deduction Proven?: Andrea FaggionDoctrix MetaphysicaeNo ratings yet

- Intel Intui N - KantDocument37 pagesIntel Intui N - KantReza KhajeNo ratings yet

- Unit 1Document13 pagesUnit 1Alok PandeyNo ratings yet

- Monet A 1974Document6 pagesMonet A 1974Emiliano Roberto Sesarego AcostaNo ratings yet

- Houlgate Kant Nietzsche and The Thing ItselfDocument43 pagesHoulgate Kant Nietzsche and The Thing ItselfLospa Stocazzo100% (1)

- Kant and The Unknown Thing-In-Itself'Document7 pagesKant and The Unknown Thing-In-Itself'Somashish NaskarNo ratings yet

- LiveRecovery Save of Empirical Concepts Universality V12Document33 pagesLiveRecovery Save of Empirical Concepts Universality V12Jorg MeurkesNo ratings yet

- Kant Presentation Short PaperDocument3 pagesKant Presentation Short PaperLucas Scott WrightNo ratings yet

- BaurDocument26 pagesBaurElisaNo ratings yet

- Kant On The Unity of The Act of Thinking: Michael J. OlsonDocument8 pagesKant On The Unity of The Act of Thinking: Michael J. OlsonMichael OlsonNo ratings yet

- Outline of Critique of Pure Reason: Transcendental Aesthetic Transcendental LogicDocument20 pagesOutline of Critique of Pure Reason: Transcendental Aesthetic Transcendental LogicImranNo ratings yet

- Noumenon - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFDocument8 pagesNoumenon - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFRodnyXSilva100% (1)

- Apperception and The Individuality of Space and TimeDocument30 pagesApperception and The Individuality of Space and Timeimmyk85No ratings yet

- KANT AND DOGMATIC IDEALISM A Defense of Kant's Refutation of Berkeley - Vance G. MorganDocument21 pagesKANT AND DOGMATIC IDEALISM A Defense of Kant's Refutation of Berkeley - Vance G. MorganTheunis HolthuisNo ratings yet

- Critique of Locke On SubstanceDocument31 pagesCritique of Locke On SubstancePaul HorriganNo ratings yet

- The Analytic of The Sublime: - Sigmund FreudDocument14 pagesThe Analytic of The Sublime: - Sigmund FreudAsim RoyNo ratings yet

- Critique of Kant On Being and ExistenceDocument27 pagesCritique of Kant On Being and ExistencePaul HorriganNo ratings yet

- Kant's Refutation of IdealismDocument17 pagesKant's Refutation of IdealismmishagdcNo ratings yet

- Descartes and The Criterion of Truth PDFDocument25 pagesDescartes and The Criterion of Truth PDFHubert SelormeyNo ratings yet

- Land Kants Spontaneity Thesis FinalDocument32 pagesLand Kants Spontaneity Thesis FinalRicardoLuisMendívilRojoNo ratings yet

- Kant's Transcendental Deduction of The CategoriesDocument18 pagesKant's Transcendental Deduction of The CategoriesKatie SotoNo ratings yet

- The Psychological Element in The Phenome PDFDocument20 pagesThe Psychological Element in The Phenome PDFMarcelo Vial RoeheNo ratings yet

- Letter of Application and The Research Proposal On Kant For Postdoctoral Fellowship in The Philosophy Department at Aarhus University - Cengiz ErdemDocument11 pagesLetter of Application and The Research Proposal On Kant For Postdoctoral Fellowship in The Philosophy Department at Aarhus University - Cengiz ErdemCengiz ErdemNo ratings yet

- The Schematism of The Pure Concepts of UnderstandingDocument12 pagesThe Schematism of The Pure Concepts of Understandingdaniellewis420No ratings yet

- III Kant and Categorical ImperativeDocument26 pagesIII Kant and Categorical ImperativehdkNo ratings yet

- CPR KANT (1) - Compressed - 88-161Document74 pagesCPR KANT (1) - Compressed - 88-161Lidra Ety Syahfitri Harahap lidraety.2022No ratings yet

- 3 - Transcendental Aesthetic - On SpaceDocument8 pages3 - Transcendental Aesthetic - On SpacesinemkrmNo ratings yet

- Ferraris2015 TrascendentalDocument18 pagesFerraris2015 TrascendentalRodrigo CarcamoNo ratings yet

- Eric Watkins - Kant and The Sciences-Oxford University Press, USA (2001) - 129-144Document16 pagesEric Watkins - Kant and The Sciences-Oxford University Press, USA (2001) - 129-144Maurizio80No ratings yet

- CPR KANT (1) - Compressed - 233-276Document44 pagesCPR KANT (1) - Compressed - 233-276Lidra Ety Syahfitri Harahap lidraety.2022No ratings yet

- Longuenesse Self - Consciousness - and - Consciousness - of BodyDocument27 pagesLonguenesse Self - Consciousness - and - Consciousness - of BodyeekeekeekeekNo ratings yet

- Eric Sanguita (Critique Paper)Document3 pagesEric Sanguita (Critique Paper)LEAH MAE CANDADONo ratings yet

- Kant and The Principle of ImmanenceDocument47 pagesKant and The Principle of ImmanencePaul HorriganNo ratings yet

- Sem. 02. Text Suplimentar GreenDocument19 pagesSem. 02. Text Suplimentar GreenUn om IntamplatNo ratings yet

- Reader Day 1 (Abstract)Document2 pagesReader Day 1 (Abstract)hamzah7abdur7raufNo ratings yet

- The Role of Sense in Acquiring Knowledge: According To St. Thomas AquaniasDocument9 pagesThe Role of Sense in Acquiring Knowledge: According To St. Thomas AquaniasDanielNo ratings yet

- Film Studies in Intecontinetal SpaceDocument1 pageFilm Studies in Intecontinetal SpaceandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Analiza Izdavačke IndustrijeDocument6 pagesAnaliza Izdavačke IndustrijeandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Analiza Kapitalističkog Svetskog SistemaDocument6 pagesAnaliza Kapitalističkog Svetskog SistemaandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Analiza Kapitalističkog Svetskog SistemaDocument6 pagesAnaliza Kapitalističkog Svetskog SistemaandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Art of The Socialist PastDocument2 pagesArt of The Socialist PastandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Analiza Kapitalističkog Svetskog SistemaDocument6 pagesAnaliza Kapitalističkog Svetskog SistemaandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Mirror of BalkanDocument210 pagesMirror of Balkanandrejkirilenko100% (1)

- Fictions Fin de Siècle, Paris, Fayard, 2000. L'espace Critique: Essai Sur L'urbanisme Et Les Nouvelles TechnologiesDocument1 pageFictions Fin de Siècle, Paris, Fayard, 2000. L'espace Critique: Essai Sur L'urbanisme Et Les Nouvelles TechnologiesandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Film Studies in Intecontinetal SpaceDocument1 pageFilm Studies in Intecontinetal SpaceandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Postmedium SyllabusDocument2 pagesPostmedium SyllabusandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Cinemaandnewmedia AY20123 Sem1-LibreDocument12 pagesSyllabus Cinemaandnewmedia AY20123 Sem1-LibreandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Ps 5Document41 pagesPs 5andrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Zbornik - Art in Critical Confrontation With Society - HRDocument611 pagesZbornik - Art in Critical Confrontation With Society - HRJana PiNo ratings yet

- Pravilnik o Izmeni Standarda Ministarstvo NaukeDocument3 pagesPravilnik o Izmeni Standarda Ministarstvo NaukeandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Ephemera: Structuring Feeling: Web 2.0, Online Ranking and Rating, and The Digital Reputation' EconomyDocument18 pagesEphemera: Structuring Feeling: Web 2.0, Online Ranking and Rating, and The Digital Reputation' EconomyandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Dialectics and Class in Marxian Economics Resnick & WolffDocument14 pagesDialectics and Class in Marxian Economics Resnick & WolffMladi Antifašisti ZagrebaNo ratings yet

- When Failure Becomes Success: Class and The Debate Over Stabilization and Adjustment David F. Ruccio Working Paper #154 - March 1991Document33 pagesWhen Failure Becomes Success: Class and The Debate Over Stabilization and Adjustment David F. Ruccio Working Paper #154 - March 1991andrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- All - Systems - Go Recovering Hans Haacke Systems ArtDocument30 pagesAll - Systems - Go Recovering Hans Haacke Systems Artandrejkirilenko100% (1)

- How Often Have We HeardDocument11 pagesHow Often Have We HeardandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- F10 Perry PaperDocument29 pagesF10 Perry PaperandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Postjugoslovenska UmetnostDocument6 pagesPostjugoslovenska UmetnostandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Subjectivity Economy SyllabusDocument8 pagesSubjectivity Economy SyllabusandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- All - Systems - Go Recovering Hans Haacke Systems ArtDocument30 pagesAll - Systems - Go Recovering Hans Haacke Systems Artandrejkirilenko100% (1)

- SerbianpostmodernDocument1 pageSerbianpostmodernandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- BertoluciDocument5 pagesBertoluciandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Louis Marin. On The Theory of Written Enunciation. The Notion of Interruption-Resumption in AutobiographyDocument11 pagesLouis Marin. On The Theory of Written Enunciation. The Notion of Interruption-Resumption in AutobiographyMiguel Ángel Maydana OchoaNo ratings yet

- GrljaVesic Neoliberal Institution of CultureDocument1 pageGrljaVesic Neoliberal Institution of CultureandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- Tito ProgramDocument14 pagesTito ProgramandrejkirilenkoNo ratings yet

- PHILO Test QuestionsDocument6 pagesPHILO Test QuestionsMaria Virginia FernandezNo ratings yet

- The Synthetic A Priori and What It Means For EconomicsDocument5 pagesThe Synthetic A Priori and What It Means For Economicsshaharhr1No ratings yet

- Intension and Extension of TermsDocument14 pagesIntension and Extension of Termseyob astatkeNo ratings yet

- Peano AxiomsDocument2 pagesPeano AxiomsJosé Antonio Martínez GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Inductivedeductive Teaching ReasoningDocument53 pagesInductivedeductive Teaching ReasoningMinjeong KimNo ratings yet

- Big Questions Important Questions Part - B Unit - I Digital FundamentalsDocument12 pagesBig Questions Important Questions Part - B Unit - I Digital FundamentalsparkaviNo ratings yet

- Daniel I.A. Cohen - Introduction To Computer Theory (1996, John Wiley & Sons) PDFDocument336 pagesDaniel I.A. Cohen - Introduction To Computer Theory (1996, John Wiley & Sons) PDFName GamNo ratings yet

- How To Argue-Philosophical Reasoning (Crash Course Philosophy #2)Document3 pagesHow To Argue-Philosophical Reasoning (Crash Course Philosophy #2)Hanz Jennica BombitaNo ratings yet

- Driscoll-Aristotles Apriori MetaphorDocument12 pagesDriscoll-Aristotles Apriori Metaphorمصطفى رجوانNo ratings yet

- Impact EvaluationDocument44 pagesImpact EvaluationJoshua Erdy Alforja Tan100% (1)

- Káčer, M - V Závoji Logiky - Právny Obzor 3-2012 PDFDocument7 pagesKáčer, M - V Závoji Logiky - Právny Obzor 3-2012 PDFMarek KacerNo ratings yet

- Probability IDocument78 pagesProbability ISnow PrinceNo ratings yet

- PS 8Document2 pagesPS 8Urvashi100% (1)

- Sas 03 Mat 152 - FLM v2Document7 pagesSas 03 Mat 152 - FLM v2zurinisaacs503No ratings yet

- The Concessive Response To SkepticismDocument12 pagesThe Concessive Response To SkepticismJohn Di GiacomoNo ratings yet

- Abstract AlgebraDocument3 pagesAbstract AlgebraLaTeXKidNo ratings yet

- MMW Midterm Exam - Google FormsDocument20 pagesMMW Midterm Exam - Google FormsCheryll PagalNo ratings yet

- Brentano's Habilitation ThesesDocument4 pagesBrentano's Habilitation ThesesAnonymous F6fBu9No ratings yet

- g2 m3 Full ModuleNew York State Common Core Mathematics Curriculum For Grade 2Document283 pagesg2 m3 Full ModuleNew York State Common Core Mathematics Curriculum For Grade 2ThePoliticalHatNo ratings yet

- Elements of ReasoningDocument2 pagesElements of ReasoningWilmar MarquezNo ratings yet

- Explain Why Critical Thinking Is Primarily About How You Think and Not Necessarily What You ThinkDocument5 pagesExplain Why Critical Thinking Is Primarily About How You Think and Not Necessarily What You ThinkMyraNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Introduction To Logic 14th Edition Copi Solutions Manual PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Introduction To Logic 14th Edition Copi Solutions Manual PDFcalymene.perdurel7my100% (10)

- El Concepto de La Intuición CategorialDocument32 pagesEl Concepto de La Intuición CategorialJuanDcoNo ratings yet

- 10.1. How Do We Acquire Knowledge?Document5 pages10.1. How Do We Acquire Knowledge?HIJRANA RanaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Foundations of Geometry 2023Document24 pagesChapter 1 Foundations of Geometry 2023Linh Chi Nguyễn ThịNo ratings yet

- Logic and Reasoning: MATH10Document69 pagesLogic and Reasoning: MATH10Syntax DepressionNo ratings yet