Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pancytopenia Secondary To Bacterial Sepsis

Uploaded by

iamralph89Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pancytopenia Secondary To Bacterial Sepsis

Uploaded by

iamralph89Copyright:

Available Formats

OVERWHELMED

A CASE OF PANCYTOPENIA SECONDARY TO SEPTICEMIA

SUBMITTED BY: RALPH LLEWEL D. SABANG VISAYAS COMMUNITY MEDICAL CENTER POST-GRADUATE INTERN

2014

ABSTRACT Alterations in peripheral blood counts resulting in aplastic anemia are commonly encountered in pediatric practice. Although bacterial septicemia is a serious clinical problem that can result to pancytopenia, there is relatively little discussion on this abnormality. This is a case of a 1 year old female child who presented with fever and cystic lesions in the face which eventually dried and formed crusts. Complete blood count and peripheral blood smear were consistent with moderate pancytopenia with associated hemodiluted and hypocellular bone marrow. Blood and wound cultures revealed Staphylococcus aureus. Patient received broad spectrum antibiotics with incision and drainage done on lesions which progressed to abscess formation. Detailed clinical history and meticulous physical examination along with baseline hematological investigations, provides invaluable information in the complete workup of pancytopenic patients. Bacterial septicemia with associated pancytopenia is fatal but treatable if managed expeditiously.

INTRODUCTION Pancytopenia is reduction in all three major formed elements of blood to levels below their lower normal limit leading to simultaneous presence of anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia.1 It is not a disease entity by itself, but rather a triad of findings. Alterations in peripheral blood counts resulting in pancytopenia are commonly encountered in pediatric practice. It is a striking feature of many serious and life threatening illnesses and may be caused by several disorders ranging from simple drug-induced bone marrow hypoplasia and megaloblastic anemia to fatal aplastic anemia, septicemia and leukemias. Etiologies are relatively different in the developing countries from the developed ones. Iron deficiency anemias and infections such as enteric fever, malaria, and bacterial sepsis are more common causes of pancytopenia in the developing countries like the Philippines. 2 Pancytopenia secondary to drug-induced hypoplasia, megaloblastosis, and leukemias have been extensively mentioned in journals. Various infections as cause of pancytopenia have been variedly documented. Fulminant bacterial sepsis as cause of pancytopenia is scarcely reported in literature, thus the aim of this paper is to report a child who developed bacterial septicemia (S. aureus) that was complicated by pancytopenia.

OBJECTIVES The specific objectives of this paper are as follows: 1. To present a case of a 1 year old female patient with complaints of fever with associated skin lesion and pancytopenia. 2. To discuss the pathophysiology of pancytopenia secondary to sepsis. 3. To present a clinical approach in diagnosing patients with pancytopenia. 4. To discuss treatment approach of patients with pancytopenia secondary to sepsis.

PATIENT PROFILE Y., M., 1 year old female, child, Filipino, Roman catholic from Kalunasan Cebu City admitted for the first time at VCMC for fever and skin lesions. Patient was born from then 30 year old G3P2 mother who had unremarkable prenatal period delivered full term via normal spontaneous vaginal delivery in a local birth clinic assisted by a midwife. No maternal complications were noted during labor and delivery. Birth weight was 7.8 lbs with no immediate postnatal complications noted. Patient was started on breastfeeding on demand until 9months of age and then was shifted to formula milk (Bonamil) since then. Complimentary feeding was started at 6months of age. Immunizations given are as follows: BCG1, DPT3, OPV3, HepB3, HiB3, AMV1, MMR1. Patients developmental assessment is at par with age. She is currently living with her parents with mother as her primary caregiver. Patient had no known medical problems nor previous hospitalizations. Patient had an upper respiratory tract infection at 9months old were she received Amoxicillin (unrecalled dose) which offered relief. Since then, no other history of antibiotic use as claimed. There were no known heredofamilial diseases as claimed. Family has no risk factors for exposure to hazardous chemicals like lead, mercury or copper. HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS Four days PTA, patient had onset of one black-brown round cystic lesion with scaly erythematous borders at the left nostril area which eventually spread to the lips the following day. The lesions were not pruritic and non-tender. Patient had no other associated symptoms like fever, bowel or bladder habit changes. Patient was still feeding well. One day PTA, lesions persisted and were now also seen at the left lower eyelid with similar characteristics. Patient then developed fever of undocumented temperature associated with decrease in appetite and irritability. Consult was done with a family physician were patient was prescribed Cloxacillin 250mg/5ml (AD 50mkD). Due to persistence of symptoms, patient was subsequently admitted.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION General Survey: awake, alert, irritable, afebrile, not in respiratory distress Temp: 36.1oC BP: 80/60mmHg HR: 156 bpm RR: 45 cpm Weight: 10kg

SKIN: warm, pale, no jaundice, good turgor HEENT: normocephalic, closed anterior fontanel, pale palpebral conjunctivae, black-brown round cystic lesions with scaly erythematous borders at left nostril, left cheek, left upper lip, left lower eyelid, non-tender, (-)nikolsky sign (Appendix A) No naso-auricular discharges noted, no oropharyngeal lesions, no lymphadenopathies C/L: equal chest expansion, clear breath sounds, no wheezing, no rales CVS: adynamic, distinct heart sounds, regular rate and rhythm ABD: globular, soft, normoactive bowel sounds, palpable liver edge 4cm below right subcostal margin, spleen was palpable EXT: warm, strong pulses, CRT <2seconds CNS: within normal limits

ADMITTING IMPRESSION:

Non-Bullous Impetigo This is mainly considered because it is the most common skin infection in children which usually appears first around the mouth and nose. The lesion begins as a tiny vesicle or pustule that ruptures and is replaced by crust formation usually brownish in color. Lesions are usually asymptomatic with occasional pruritus. Surrounding erythema maybe present. All these were seen with the patient.

DIFFERETTIAL DIAGNOSIS:

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome (SSSS) An early state of this syndrome can start with macular erythema followed by blister formations and progressing to diffuse epidermal exfoliation. The patient also presented with fever and irritability which is mainly present in patients with SSSS. The progress of lesions to areas with no history of trauma makes this diagnosis also a possibility.

COURSE IN THE WARD Upon admission patient was alert, irritable, afebrile and not in respiratory distress. Venoclysis was started with D5 0.3% NaCl and the following laboratories were taken: CBC showed moderate pancytopenia (Appendix B); decreased Reticulocyte count (0.1%); increased C-reactive protein (345.69 mg/L). Peripheral blood smear noted normocytic and normochromic red blood cells with slight variation in size and shape. There was marked leukopenia and inadequate platelets seen. Chest radiograph showed pneumonia on both inner lung zones. Urinalysis showed pyuria (10-20 cells/hpf). Blood and wound cultures were taken and patient was started on Fluocloxacillin 500mg IV q8hours (AD: 150mkD), and Ceftazidime 500mg IVTT q8hours (AD: 150mkD). Patient was transfused with one unit of platelet concentrate. On the first to third hospital day, patients condition deteriorated. Patient was noted to be lethargic, tachypneic (60 cpm) and febrile (highest temp 38.9 oC). Cystic lesions are now noted on the oral mucous membranes (upper vermillion area) and a palpable mass was observed on the right scapular area which was 3x5cm in size, round, smooth, soft, warm to touch, and tender. Oxygen was provided via nasal cannula and antibiotics were shifted to

Vancomycin 150mg IV q6hours (AD: 15mkd) and Meropenem 200mg IV q8hours (AD: 20mkd) based on culture and sensitivity results (Appendix C). Additional laboratories revealed: normal for age serum creatinine (0.35 mg/dl), decreased serum uric acid (2.06mg/dl), slightly increased SGPT (50 U/L), increased LDH (348 U/L). One unit of PRBC was transfused in 3 aliquots. Bone marrow aspiration was done which revealed hypocellular bone marrow with no blasts seen.

On the fourth to twelfth hospital day, patients condition gradually improved. Vital signs were within normal range. Facial lesions were noted to be dry with crust formations. Incision and drainage was done on the right scapular mass. Serial CBC showed increasing to eventually normal cell counts. Echocardiogram was taken and revealed mild tricuspid regurgitation, no vegetation or pericardial effusion noted. Patient was discharged with improve condition. FINAL DIAGNOSIS: Septicemia secondary to Staphylococus aureus

DISCUSSION Sepsis is defined as the presence (probable or documented) of infection together with systemic manifestations of infection. Dysfunction of the hematologic system is an early manifestation of severe sepsis and is seen in virtually all patients with this disease. The most common abnormalities of the hematologic system in patients with sepsis is anemia, leukocytosis and thrombocytopenia.3 The patient presented initially with skin lesions and fever which then deteriorated. Initial laboratories revealed moderate pancytopenia with associated decreased reticulocytosis. Blood culture revealed positive growth to Staphylococcus aureus. Most literatures state that pancytopenia can occur after infection with many of the hepatitis viruses, herpes viruses, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus and HIV.1 A large series on etiological appraisal of pancytopenia by Jain et al identified 25.6% incidence of infection as a cause.4 In the study, AIDS (30) was predominant followed by septicemia (14). In a separate study done by Chhabra et al, 19.7% (18 of 91 cases) had infection as a cause of pancytopenia, 2 cases were identified as severe.5 Fulminant bacterial sepsis as a cause of pancytopenia is scarcely reported in literature. Memon et al reported incidence of 8.69% (20 of 220 cases) had all three cell lines affected due to sepsis at presentation to hospital. Eight of those patients had gram negative bacterial sepsis 4 with Klebsiella and 4 with Pseudomonas.2 In the study done by Chhabra et al, 2 patients presented with fulminant bacterial sepsis whom both with Klebsiella-positive cultures.5

PATHOGENESIS The most common abnormalities of the hematologic system in patients with sepsis is anemia, leukocytosis and thrombocytopenia. Rarely, severe sepsis may result in reduction of all three major formed elements of blood, as what the above patient presented. Amos and colleagues performed bone marrow biopsies on 24 ICU patients and noted that all patients manifested anemia attributable to bone marrow suppression, which was suggested by impaired growth of bone marrow cells upon bone marrow culture.6 During sepsis, numerous inflammatory cytokines are released such as IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor. These and other inflammatory mediators have an overall suppressive effect on hematopoiesis, which results in the clinical phenotype of anemia.7 Thrombocytopenia occurs in up to 65% of patients with bacteremia and results from decreased platelet production, increased platelet utilization, and immune destruction. 8 In sepsis, platelets adhere to activated endothelium in multiple organs. Following adhesion, activated platelets may either dislodge and return to circulation or release their granule contents and undergo irreversible aggregation with viscous metamorphosis. Inflammatory mediators and bacterial products such as endotoxin can contribute to sepsis-associated thrombocytopenia by enhancing platelet reactivity and adhesivity. Patients with severe sepsis and thrombocytopenia may also have hypoproliferative bone marrow with decreased numbers of megakaryocytes which is attributable to increased inflammatory cytokines. 9 Neutrophilic leukocytosis is a more common manifestation of sepsis. It appears to result from a combination of factors including recruitment of mature neutrophils from the marginating pool into the circulating pool, mobilization of mature and developing neutrophils from the bone marrow and eventually increased leucopoiesis. In some instances, neutropenia can present which can be the result of depletion of bone marrow granulocyte precursors, a granulocytic maturation arrest or migration of leukocytes into the infected focus in numbers in excess of the bone marrows ability to replace them in a timely fashion.9 Another possible explanation of pancytopenia in bacterial sepsis is the presence of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is an unusual

syndrome characterized by fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and the pathologic finding of hemophagocytosis (phagocytosis by macrophages of erythrocytes, leukocytes, platelets and their precursors) in bone marrow and other tissues. Hyperproduction of cytokines. Including interferon- and tumor necrosis factor- may play a role in the pathogenesis of HLH.10 This condition is mainly considered because the patient fulfilled 3 out of the 8 symptom criteria established to diagnose HLH (Appendix D). The patient presented with fever, pancytopenia and hepatosplenomegaly. Other laboratories needed to fulfil the criteria namely; serum triglycerides, fibrinogen and ferritin were not taken. The presence hemophagocytosis was not mentioned in the bone marrow analysis. DIAGNOSIS Acquired pancytopenia is typically characterized by anemia, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia in the setting of elevated serum cytokine values. A careful history of exposure to known risk factors should be obtained for every child presenting with pancytopenia. Even in the absence of the classic associated findings, the possibility of a genetic predisposition to bone marrow failure should always be considered.1 Inherited pancytopenias account for approximately 30% of cases of pediatric marrow failure. Fanconi anemia is the most common of these disorders. 1 Careful examination of the peripheral blood smear for RBC, leukocyte and platelet morphologic features is important. A reticulocyte count should be performed to assess erythropoietic activity. The patient had moderate pancytopenia with the following specific values: WBC= 0.71K/uL, total RBC= 2.06 M/uL, Platelet count = 22K/uL, Hemoglobin = 5.09 g/dl, Hematocrit = 17%. The patients reticulocyte count was also decre ased (0.1%). In patients with pancytopenia associated with decreased reticulocyte count, bone marrow failure should be investigated (Appendix E) thus a bone marrow study was done with the patient. Bone marrow examination should include both aspiration and a biopsy, and the marrow should be carefully evaluated for morphologic features, cellularity and cytogenetic findings.1 The patient only had bone marrow aspiration which showed hypocellular bone marrow with no blasts seen. With this, more common etiologies of bone marrow failure like leukemia and

myelodysplastic syndrome have been ruled out because these diseases usually present with hypercellular marrow. There was also no mention of hemophagocytosis seen which makes reactive hemophagocytic reaction secondary to bacterial sepsis less likely. TREATMENT The treatment of children with acquired pancytopenia requires comprehensive supportive care coupled with an attempt to treat the underlying marrow failure. As most haematological complications are usually self-limited, the management of such during sepsis is fraught with difficulties. If clinically indicated, initiate a blood transfusion using specific cells, such as packed red cells for anemia and platelets for thrombocytopenia. Clinical indications for red cell transfusions are symptoms secondary to anemia and bleeding from thrombocytopenia (Appendix F). The RBC product of choice for children is the standard suspension of RBCs separated from whole blood by centrifugation (PRBC). One unit of PRBC is expected to result in 1g/dl and 3% increase in hemoglobin and hematocrit respectively.1 The patient received one unit of PRBC and platelet concentrate which resulted to improvement of blood cell counts (Appendix B). Supportive care gives only temporary relief of symptoms and does not treat the primary disease. Infections resulting in pancytopenia should be treated as emergencies. After blood is drawn and other cultures are taken, broad-spectrum antibiotics should be started empirically in the presence of febrile neutropenia. Coverage for the most common gram-positive and gramnegative organisms should be considered. The choice can be altered later, depending on the results of sensitivity tests from positive cultures.11 Parenteral Ceftazidime and Floucloxacillin was given empirically but the patient deteriorated. Vancomycin and Meropenem were then used after culture and sensitivity test results were available. This provided progressive improvement in patients status. The use of corticosteroids during the acute infection carries the risk of dissemination but is of proven value when bone marrow hypoplasia is diagnosed. The administration of high-dose intravenous methylprednisone has been reported and has led to the normalization of bone marrow function.11 The need for corticosteroids in the case presented was not entertained

because the patient was progressively improving after blood transfusion and appropriate antibiotics. CONCLUSION Detailed clinical history and meticulous physical examination along with baseline haematological investigations provide invaluable information in the evaluation of pancytopenic patients, helping in systematic planning of further investigations to diagnose and ascertain the cause, avoiding unnecessary tests which not only add to the expense of treatment but sometimes also may result in delayed diagnoses and treatment. Overwhelming bacterial infections and septicemia as a cause of pancytopenic presentation particularly in developing countries should always be kept in mind. Early and aggressive treatment initiation should be a priority in these patients, as, if left untreated the prognosis is bad. CASE SUMMARY This is a case of 1 year old female child with unremarkable past medical history who presented with 4 days fever associated skin lesions in the face. Initial impression upon admission was Non-bullous impetigo to rule out Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Complete blood count and peripheral blood smear were consistent with moderate pancytopenia with associated bone marrow failure thus leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome and reactive hemophagocytic syndrome were entertained. Other laboratories taken showed increased in C-reactive protein, LDH, SGPT. Pyuria was noted and pneumonia was evident on chest radiograph. Bone marrow aspiration revealed hemodiluted and hypocellular bone marrow with no evidence of hemophagocytosis which ruled out other bone marrow failure etiologies previously mentioned. Blood and wound cultures revealed staphylococcus aureus. The patient was then managed for pancytopenia secondary to severe bacterial sepsis. Supportive blood transfusion were done and broad spectrum antibiotics (Vancomycin and Meropenem) were given which provided gradual improvement of the patient. Patient was discharged with improved condition without residual complications noted. Final diagnosis was Septicemia secondary to Staphylococcus aureus.

REFERENCES 1. Robert Kliegman et al. Nelson textbook of paediatrics 19th edition. Elsevier Saunders. 2011 2. Shazia Memon et al. Etiological Spectrum of Pancytopenia based on bone marrow examination in children. Journal of the college of physicians and surgeons Pakistan, Vol. 18 (3): 163-167 3. Dellinger RP et al. Surviving sepsis Campaign: International guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Intensive care medicine 2008. 34:17-60 4. Arvind Jain, Manjiri Naniwadekar. An Etiological reappraisal of pancytopenia largest series reported to date from a single tertiary care teaching hospital. BMC Hematology 2013, 13:10. http://biomedcentral.com/2052-1839/13/10 5. Amieleena Chhabra et al. Clinico aetiological profile of pancytopenia in pediatric practice. Journal, Indian Academy of Clinical Medicine. Vol 13 No. 4. October-December 2012 6. Amos RJ, Deane M, Ferguson C, et al. Observations on the haemopoietic response to critical illness. J Clin Pathol 1990.43: 8506 7. Weiss G, Goodnough LT. Anemia of chronic disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2005. 352:101123 8. Marks PW, Rosenthal DS. Hematologic manifestations of systemic disease: infection, chronic inflammation, and cancer. Philadelphia. Churchill Livingstone 2005. 257384 9. Richert E. Goyette et al. Hematologic changes in sepsis and their therapeutic implications. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine. Vol 25 No. 6. 2004 10. David N. Fisman. Hemophagocytic syndromes and infection. Emerging Infectious Diseases. Vol 6 No. 6 November-December 2000 11. Srikanth Nagalla et al. Bone marrow failure treatment and Management. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/199003-treatment#aw2aab6b6b2 12. Richiard Sills. Practical algorithms in pediatric hematology and oncology. Karger Publisher. 2003

APPENDIX A

Figure 1: Facial lesion on admission

Figure 2: Facial lesions on 7th hospital day

Figure 3: Facial lesions on 12th hospital day

APPENDIX B Table 1: COMPLETE BLOOD COUNT White Blood Cells (K/uL) Segmenters (%) Lymphocytes (%) Monocytes (%) Eosinophils (%) Basophils (%) Red Blood Cells (M/uL) Hemoglobin (g/dl) Hematocrit (%) MCV (fL) MCH (pg) MCHC (g/dl) RDW-CV (%) Platelet (K/uL) MPV (fL) APPENDIX C Table 2: Blood and wound culture and sensitivity results SPECIMEN CULTURE SENSITIVE TO: Blood Right Arm Staphylococcus aureus Vacomycin Meropenem Levofloxacin Chloramphenicol Clindamycin Ciprofloxacin Gentamycin Penicllin-G Sulfamethoxazole & Trimethoprim Right Cheek Lesion Staphylococcus aureus Cefepime Meropenem Levofloxacin Vancomycin Gentamycin Sulfamethoxazole & Trimethoprim Right Scapula Abscess Enterobacter sakazaki Amikacin Cefepime Cefixime Cefoperazone Ceftriaxone Cefuroxime Chloramphenicol Gentamycin Netilmycin Ceftazidime Ciprofloxacin Piperacillin/Tazobactam Meropenem Levofloxacin Ampicillin Amoxicillin/Clavulanate FEBRUARY 2 0.7 15 80 5 0 0 2.06 5.09 17 74.9 24.7 33 14.3 22 8.05 FEBRUARY 5 0.9 51 31 11 3 4 3.95 10.2 30.8 78.1 25.9 33.1 14.7 24 8.69 FEBRUARY 7 3.11 34 55 10 0 1 4.26 10.7 33 78.7 25 31.8 14.5 34 9.95 FEBRUARY 12 7.05 50 34 14 2 0 4.18 10.7 33.3 79.6 25.6 32.1 15 308 6.58

RESISTANT TO:

Azithromycin Erythromycin Oxacillin

Azithromycin Erythromycin Oxacillin Penicllin G

APPENDIX D Table 3: Diagnostic Guidelines for HLH1 The Diagnosis of HLH is established by fulfilling 1 or 2 of the following criteria: 1. A molecular diagnosis consistent with HLH ( e.g., PRF mutations, SAP mutations) OR 2. Having 5 out 8 of the following: a. Fever b. Splenomegaly c. Cytopenia (affecting cell lineages; haemoglobin 9 g/dl (or 10 g/dl for infants <4 wk of age, platelets <100,000 /uL, neutrophils <1000/uL d. Hypertriglyceridemia (265 mg/dl) and or hypofibrinogenemia (150 mg/dl) e. Hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, spleen, or lymph nodes without evidence of malignancy f. Low or absent NK cell cytotoxicity g. Hyperferritinemia (500 ng/ml) h. Elevated soluble CD25 (2400 U/ml) APPENDIX E

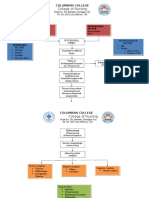

FIGURE 4: Approach to Pancytopenia 12

APPENDIX F Table 5: Guidelines for Pediatric Red blood Cell Transfusions1 CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS Acute loss of >25% of circulating blood volume Hemoglobin <8.0 g/dl in the perioperative period Hemoglobin <13 g/dl and severe cardiopulmonary disease Hemoglobin <8 g/dl and symptomatic chronic anemia Hemoglobin <8 g/dl and marrow failure INFANTS 4 MONTHS OLD Hemoglobin <13 g/dl and severe pulmonary disease Hemoglobin <10 g/dl and moderate pulmonary disease Hemoglobin <13 g/dl and severe cardiac disease Hemoglobin <10 g/dl and major surgery Hemoglobin <8 g/dl and symptomatic anemia Table 6: Guidelines for Pediatric Platelet Transfusion1 CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS Platelet count <50 K/L and beeding Platelet count <50 K/L and an invasive procedure Platelet count <20 K/L and marrow failure with hemorrhagic risk factors Platelet count <10 K/L and marrow failure without hemorrhagic risk factors Platelet count at any level, but with platelet dysfunction plus bleeding or an invasive procedure INFANTS 4 MONTHS OLD Platelet count <100 K/L and bleeding or during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation Platelet count <50 K/L and an invasive procedure Platelet count <20 K/L and clinically stable Platelet count <50 K/L and clinically unstable Platelet count at any level, but with platelet dysfunction plus bleeding or an invasive procedure

You might also like

- NCM 112 Rle: A Case Study On: Typhoid FeverDocument17 pagesNCM 112 Rle: A Case Study On: Typhoid FeverMadelyn Serneo100% (1)

- Iron Deficiency AnemiaDocument5 pagesIron Deficiency AnemiaLoiegy PaetNo ratings yet

- Case Study PneumoniaDocument14 pagesCase Study PneumoniaJester GalayNo ratings yet

- Stem Cells EssayDocument4 pagesStem Cells EssayalskjdhhNo ratings yet

- Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaDocument25 pagesAcute Lymphoblastic Leukemiaapi-396564080No ratings yet

- RabiesDocument10 pagesRabiesWinda LiraNo ratings yet

- Hyporeninemic HypoaldosteronismDocument12 pagesHyporeninemic HypoaldosteronismCésar Augusto Sánchez SolisNo ratings yet

- Acute Appendicitis Diagnosis and ManagementDocument57 pagesAcute Appendicitis Diagnosis and ManagementYS NateNo ratings yet

- Addison's Disease: Adrenal Insufficiency and Adrenal CrisisDocument15 pagesAddison's Disease: Adrenal Insufficiency and Adrenal CrisisMaryONo ratings yet

- Steven Johnson SyndromeDocument13 pagesSteven Johnson SyndromeKhairul AnwarNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Meningococcal Meningitis and SepticaemiaDocument8 pagesPathophysiology of Meningococcal Meningitis and SepticaemiaEugen TarnovschiNo ratings yet

- Rabies: Ragina AguilaDocument55 pagesRabies: Ragina AguilaCharles Lester AdalimNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument12 pagesDrug StudyIsha Catimbang GenerilloNo ratings yet

- What Is LeukemiaDocument11 pagesWhat Is LeukemiaNazneen RagasaNo ratings yet

- Etiology of HypertensionDocument7 pagesEtiology of HypertensionAdelia Maharani DNo ratings yet

- Dermatological History and Examination PDFDocument5 pagesDermatological History and Examination PDFHesbon MomanyiNo ratings yet

- Dengue Fever Signs, Symptoms, and PreventionDocument9 pagesDengue Fever Signs, Symptoms, and PreventionKyla BalboaNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic SyndromeDocument56 pagesNephrotic SyndromeMurugesan100% (1)

- 2.11 SEPTIC ABORTION AND SEPTIC SHOCK. M. Botes PDFDocument4 pages2.11 SEPTIC ABORTION AND SEPTIC SHOCK. M. Botes PDFteteh_thikeuNo ratings yet

- Alzheimer Disease: A Major Public Health ConcernDocument6 pagesAlzheimer Disease: A Major Public Health ConcerndineshhissarNo ratings yet

- Acute Sinusitis 08Document2 pagesAcute Sinusitis 08ativonNo ratings yet

- UtiDocument38 pagesUtiAzra AzmunaNo ratings yet

- Pancreatic AdenocarcinomaDocument6 pagesPancreatic AdenocarcinomafikriafisNo ratings yet

- Medical Analysis One Flew Over The CuckoDocument6 pagesMedical Analysis One Flew Over The CuckoAgronaSlaughterNo ratings yet

- 2-Sickle Cell Anemia PDFDocument21 pages2-Sickle Cell Anemia PDFJennyu YuNo ratings yet

- Amoebiasis in Wild Mammals: Ayesha Ahmed M Phil. Parasitology 1 Semester 2013-Ag-2712Document25 pagesAmoebiasis in Wild Mammals: Ayesha Ahmed M Phil. Parasitology 1 Semester 2013-Ag-2712Abdullah AzeemNo ratings yet

- Antiemetic Prophylaxis For CINV NEJM 2016Document12 pagesAntiemetic Prophylaxis For CINV NEJM 2016tcd_usaNo ratings yet

- GRP 20 Final Abscess Case StudyDocument14 pagesGRP 20 Final Abscess Case StudyBorja, Kimberly GraceNo ratings yet

- Chelsea Amman Pku Case StudyDocument37 pagesChelsea Amman Pku Case Studyapi-365955738No ratings yet

- Vaginal CandidiasisDocument31 pagesVaginal CandidiasisMutabazi Sharif100% (1)

- Acute Disease Case Study: Metabolism - HypothermiaDocument8 pagesAcute Disease Case Study: Metabolism - HypothermiaRegina PerkinsNo ratings yet

- Sjogren'S Syndrome: Guided By: Dr. Richa MohanDocument17 pagesSjogren'S Syndrome: Guided By: Dr. Richa MohanAnkyNo ratings yet

- Asthma Pathophysiology and Risk FactorsDocument98 pagesAsthma Pathophysiology and Risk FactorsyayayanizaNo ratings yet

- Rare Muscle Diseases: PM and DMDocument2 pagesRare Muscle Diseases: PM and DMintrovoyz041No ratings yet

- Cushings SyndromeDocument9 pagesCushings SyndromeMavra Imtiaz100% (1)

- Acute Poststreptococcal GlomerulonephritisDocument69 pagesAcute Poststreptococcal GlomerulonephritisJirran CabatinganNo ratings yet

- Tuberculous MeningitisDocument11 pagesTuberculous MeningitiszuhriNo ratings yet

- Poststreptococcal Glomerulonephritis - UpToDateDocument21 pagesPoststreptococcal Glomerulonephritis - UpToDateHandre Putra100% (1)

- Hepatitis VirusDocument37 pagesHepatitis Virusapi-19916399No ratings yet

- Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis JIA or JRA: What's in A Name?Document63 pagesJuvenile Idiopathic Arthritis JIA or JRA: What's in A Name?Rajesh BalakrishnanNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument11 pagesCase Studyapi-352549797No ratings yet

- A. Antineoplastic DrugsDocument48 pagesA. Antineoplastic DrugsKim Shyen BontuyanNo ratings yet

- STEM Activity Plan and Patient CaseDocument8 pagesSTEM Activity Plan and Patient CaseJay Villasoto100% (1)

- Blood DisordersDocument8 pagesBlood DisordersDeevashwer Rathee100% (1)

- Anatomy and Physiology - Breast and LymphDocument3 pagesAnatomy and Physiology - Breast and LymphNkk Aqnd MgdnglNo ratings yet

- Assisting: Venous Cut DownDocument4 pagesAssisting: Venous Cut DownJimnah Rhodrick BontilaoNo ratings yet

- Alzheimer's DiseaseDocument19 pagesAlzheimer's DiseaseMission JupiterNo ratings yet

- Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Literature ReviewDocument38 pagesJuvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Literature ReviewpernandaselpiaNo ratings yet

- Patho DSDocument10 pagesPatho DSJesselyn CampitNo ratings yet

- Administering Medication Via A Small-Volume NebulizerDocument2 pagesAdministering Medication Via A Small-Volume NebulizerJerilee SoCute WattsNo ratings yet

- PATHODocument9 pagesPATHOj_averilla2012No ratings yet

- HIV/AIDS Determinants and Control FactorsDocument4 pagesHIV/AIDS Determinants and Control FactorsahiNo ratings yet

- Types of Leukemia ExplainedDocument4 pagesTypes of Leukemia ExplainedwizardebmNo ratings yet

- New Era University: Reflection Paper Day 1-3Document3 pagesNew Era University: Reflection Paper Day 1-3Del Rosario, Sydney G.No ratings yet

- Derma Notes 1Document31 pagesDerma Notes 1KirstinNo ratings yet

- 18 IM 3.02 Systemic Lupus ErythematosusDocument8 pages18 IM 3.02 Systemic Lupus ErythematosusKaykie CalambaNo ratings yet

- Cataract 1 Lecture PmcajkDocument33 pagesCataract 1 Lecture PmcajkAbdul Munim KhanNo ratings yet

- Complete Blood CountDocument5 pagesComplete Blood CountShella CondezNo ratings yet

- CyclosporineDocument3 pagesCyclosporineraki9999No ratings yet

- A Study of the Lack of Hiv/Aids Awareness Among African American Women: a Leadership Perspective: Awareness That All Cultures Should Know AboutFrom EverandA Study of the Lack of Hiv/Aids Awareness Among African American Women: a Leadership Perspective: Awareness That All Cultures Should Know AboutRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Relationship Between Family Background and Academic Performance of Secondary School StudentsDocument57 pagesThe Relationship Between Family Background and Academic Performance of Secondary School StudentsMAKE MUSOLININo ratings yet

- 2020 Book WorkshopOnFrontiersInHighEnerg PDFDocument456 pages2020 Book WorkshopOnFrontiersInHighEnerg PDFSouravDeyNo ratings yet

- Arx Occasional Papers - Hospitaller Gunpowder MagazinesDocument76 pagesArx Occasional Papers - Hospitaller Gunpowder MagazinesJohn Spiteri GingellNo ratings yet

- BI - Cover Letter Template For EC Submission - Sent 09 Sept 2014Document1 pageBI - Cover Letter Template For EC Submission - Sent 09 Sept 2014scribdNo ratings yet

- Midgard - Player's Guide To The Seven Cities PDFDocument32 pagesMidgard - Player's Guide To The Seven Cities PDFColin Khoo100% (8)

- MiQ Programmatic Media Intern RoleDocument4 pagesMiQ Programmatic Media Intern Role124 SHAIL SINGHNo ratings yet

- What Is Love? - Osho: Sat Sangha SalonDocument7 pagesWhat Is Love? - Osho: Sat Sangha SalonMichael VladislavNo ratings yet

- Settlement of Piled Foundations Using Equivalent Raft ApproachDocument17 pagesSettlement of Piled Foundations Using Equivalent Raft ApproachSebastian DraghiciNo ratings yet

- Device Exp 2 Student ManualDocument4 pagesDevice Exp 2 Student Manualgg ezNo ratings yet

- 05 Gregor and The Code of ClawDocument621 pages05 Gregor and The Code of ClawFaye Alonzo100% (7)

- Online Statement of Marks For: B.A. (CBCS) PART 1 SEM 1 (Semester - 1) Examination: Oct-2020Document1 pageOnline Statement of Marks For: B.A. (CBCS) PART 1 SEM 1 (Semester - 1) Examination: Oct-2020Omkar ShewaleNo ratings yet

- 2C Syllable Division: Candid Can/dDocument32 pages2C Syllable Division: Candid Can/dRawats002No ratings yet

- Bianchi Size Chart for Mountain BikesDocument1 pageBianchi Size Chart for Mountain BikesSyafiq IshakNo ratings yet

- AI Capstone Project Report for Image Captioning and Digital AssistantDocument28 pagesAI Capstone Project Report for Image Captioning and Digital Assistantakg29950% (2)

- MM-18 - Bilge Separator - OPERATION MANUALDocument24 pagesMM-18 - Bilge Separator - OPERATION MANUALKyaw Swar Latt100% (2)

- The Highest Form of Yoga - Sant Kirpal SinghDocument9 pagesThe Highest Form of Yoga - Sant Kirpal SinghKirpal Singh Disciple100% (2)

- Year 11 Economics Introduction NotesDocument9 pagesYear 11 Economics Introduction Notesanon_3154664060% (1)

- Will You Be There? Song ActivitiesDocument3 pagesWill You Be There? Song ActivitieszelindaaNo ratings yet

- Oyo Rooms-Case StudyDocument13 pagesOyo Rooms-Case StudySHAMIK SHETTY50% (4)

- Pharmaceuticals CompanyDocument14 pagesPharmaceuticals CompanyRahul Pambhar100% (1)

- P.E 4 Midterm Exam 2 9Document5 pagesP.E 4 Midterm Exam 2 9Xena IngalNo ratings yet

- Tong RBD3 SheetDocument4 pagesTong RBD3 SheetAshish GiriNo ratings yet

- BCIC General Holiday List 2011Document4 pagesBCIC General Holiday List 2011Srikanth DLNo ratings yet

- A Review On Translation Strategies of Little Prince' by Ahmad Shamlou and Abolhasan NajafiDocument9 pagesA Review On Translation Strategies of Little Prince' by Ahmad Shamlou and Abolhasan Najafiinfo3814No ratings yet

- GCSE Ratio ExercisesDocument2 pagesGCSE Ratio ExercisesCarlos l99l7671No ratings yet

- Chapter 12 The Incredible Story of How The Great Controversy Was Copied by White From Others, and Then She Claimed It To Be Inspired.Document6 pagesChapter 12 The Incredible Story of How The Great Controversy Was Copied by White From Others, and Then She Claimed It To Be Inspired.Barry Lutz Sr.No ratings yet

- LLB 1st Year 2019-20Document37 pagesLLB 1st Year 2019-20Pratibha ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Administrative Law SyllabusDocument14 pagesAdministrative Law SyllabusKarl Lenin BenignoNo ratings yet

- Classen 2012 - Rural Space in The Middle Ages and Early Modern Age-De Gruyter (2012)Document932 pagesClassen 2012 - Rural Space in The Middle Ages and Early Modern Age-De Gruyter (2012)maletrejoNo ratings yet

- Professional Ethics AssignmentDocument12 pagesProfessional Ethics AssignmentNOBINNo ratings yet