Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Exercise Program

Uploaded by

Fayasulhusain MuthalibCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Exercise Program

Uploaded by

Fayasulhusain MuthalibCopyright:

Available Formats

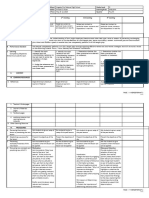

Exercise Program Guidelines

Author: Anne Jones (ASH, Physiotherapy Dept)

[Editor: This section is included because some practitioners may feel more comfortable with more detailed instructions on promoting exercise among their clients. Further, some people come to a health service seeking technical advice on how they should be exercising, and it seems some people respond well to a prescription (medicalisation of exercise) of exercise and Active Australia has encouraged this from GPs in the past. It was not included as a protocol in the CARPA STM as it may have limited applicability. Future feedback from users of the STM will guide its inclusion in future editions.]

Guidelines

Exercise benefits people with the following conditions:

Chronic lung disease Cardiac disease Hypertension Diabetes Obesity Everyone!

How to promote exercise with patients

Encourage the person to start with an activity that they enjoy. For example, brisk walking, swimming, football, lifting weights. If the person hasnt exercised for a while, measure the persons heart rate and blood pressure taken prior to starting the person on an exercise program. Encourage the person to exercise at a set time each day and to try and stick to this time. Explain to the person that they should not exercise when it is hot or very cold as this can over stress the body. Encourage the person to exercise with another person, as it is more fun. Explain to the person that they need to exercise at a level which allows them to carry on talking, saying four to five words between breaths. The person should not be gasping for breath but would be unable to sing a song if asked to. The exercise should cause a light sweat and feel somewhat hard. The person may be able to exercise only for five minutes or up to 40 minutes. Explain to the person that they need to exercise for as long as they are able to, three to five times a week. Encourage the person to warm up by starting with a slow walk for about five minutes if able. They should then do some stretching exercises.

The person then does their exercise. After exercising the person needs to walk slowly for five minutes and do some gentle stretches to cool down. The person will find that exercising will become easier as the weeks progress. The person needs to then increase the time that they spend exercising or increase how hard they exercise. Initially exercise should begin at 6070% of maximum heart rate and progress over four to six weeks to 7580% of maximum heart rate.

Precautions

Explain to the person that if they develop increased shortness of breath, so that talking is difficult whilst exercising, that they should exercise at a slower pace or stop exercising and get more advice on their exercise plans. Explain to the person that if they develop chest pain, become wheezy, feel nauseated, become dizzy, become very tired or start coughing up blood, stop exercising immediately and go to the health clinic. Explain to the person that they should not exercise after a meal for at least one to three hours. Explain to the person that they need to take their medication as directed by the doctor. For example, if they take a bronchodilator and get short of breath on exercise then they need to take their bronchodilator 15 mins prior to exercising.

People needing a review by the doctor before commencing exercise

Recent cardiac surgery, MI or episode of unstable angina Moderate to severe cardiac disease Recent thoracic surgery Severe pulmonary disease Unstable diabetes Moderate to severe hypertension Pregnant women

How to work out a persons training heart rate

220 the persons age = maximum heart rate. Maximum heart rate x 6080% = training heart rate range. Lets say the person is 35 years old: 220 35 = 185 (MaxHR) 185 x 0.6 = (60% training percentage) = 111 185 x 0.8 = (80% training percentage) = 148 Training heart rate range = 111148

Exercise program theory

Exercise has been proven to be beneficial in the treatment and prevention of many conditions. Physical inactivity is estimated to be responsible for about 7% of the total burden of disease in Australia (Mathers et al. 1999). This places it second behind tobacco in terms of importance in health promotion and disease control (AIHW 2000). Forty-three per cent of adult Australians did not undertake appropriate levels of physical activity to achieve health benefits (AIHW 2001). The exercise guidelines in the CARPA manual were designed from guidelines and research already undertaken and published in a wide range of places. Although many of the guidelines have been developed using non-

Indigenous people, population-based studies show that they are applicable to a wide range of populations (AIHW 2000). These guidelines are applicable to the Aboriginal population as many of the diseases that exercise can benefit are seen in the Indigenous population (Swanson 1999, Walsh 2001). Cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, obesity, diabetes and hypertension are diseases prevalent in the Indigenous community. The National Heart Foundation reports that . . . people who are not physically active are twice as likely to die from coronary heart disease as those who are . . . (Shilton et al. 2001). Ian Ring (cited in Walsh 2001) states that mortality from ischaemic heart disease is twice as high in the Aboriginal population as compared with the non-Aboriginal population, being six to eight times higher in the age range of 2564 years. Smoking is twice as common in Aboriginals as compared with non-Aboriginals, type 2 diabetes is two to four times higher and obesity and low physical activity is common. Forty per cent of Aboriginals reported no leisure time physical activity compare with 34% for other Australians (ABS 1995). In 1995 the highest levels of physical inactivity was reported in the NT (40%) compared to all other states (ABS 1995). Over seven million Australians 25 and over are overweight, two million are classified as obese and three million have high blood pressure (AIHW 2001). Research has shown that moderate levels of exercise can: Reduce systolic and diastolic blood pressure (AIHW 2001, Chisholm et al. 1994, NCPAD 2000, Rockville 1995, Shilton et al. 2001) on average by 11 and 8 mmHg respectively (Taylor 2002) Improve exercise tolerance significantly in patients with chronic respiratory disease (Ries et al. 1997) and cardiac disease (Rockville, 1995) Improve the symptoms of dyspnea in chronic respiratory disease patients (Ries et al. 1997) Improve blood lipids by reducing total cholesterol by 6%, reduce low density lipoprotein by 10% and increase high density lipoprotein by 5% (AIHW 2001, Chisholm et al. 1994, Shilton et al. 2001) Favourably influence body weight (AIHW 2001, Chisholm et al. 1994, Henry 2002, NCPAD 2000, Shilton et al. 2001, Whedon & Dobbins 2000) Prevent 3050% of new cases of type 2 diabetes (AIHW 2000) Help improve quality of life (AIHW 2000) The exercise guidelines are consistent with all of the guidelines referenced below (except for How to work out a persons training heart rate). The more accurate way includes using a persons resting heart rate in the equation, but this is more difficult and is likely to deter people from measuring their training heart rate. Therefore, the less accurate equation was chosen as the recommendation. Having a training heart rate is needed to determine the intensity level of exercise. Exercising three to five times a week and preferably for 2040 minutes has been shown to give the effects stated above. For those who are unable to exercise for 20 minutes then starting at a level that is obtainable and gradually increasing the time is better than no exercise. Moderate intensity exercise has been shown to be all that is needed and using a target heart rate is the easiest and most reliable measure of intensity of exercise. If the intensity is too low or high then the benefits of exercise appear to be reduced (AIHW 2000). Moderate intensity exercise places people at a lower risk of cardiovascular incident whilst providing safety and beneficial effects (AIHW 2001). Hagberg and Associates (as cited in Taylor 2002)

reported that moderate activity produced on average 50% greater reduction in systolic blood pressure as compared to high intensity exercise. They also reported that the diastolic blood pressure had slightly larger decreases when moderate exercise was performed as compared with intense exercise (AHCPR 1995, Chisholm et al. 1994, National Cardiac Rehabilitation Advisory Committee 2000, Ries et al. 1997, Shilton et al. 2001, Taylor 2002, Whedon & Dobbins 2000).

Guidelines developed from:

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS): 19891990, 1995 National Health Surveys. AHCPR (1995): Clinical practice guideline no.17 Cardiac rehabilitation. Table 16 Alternative approaches to cardiac rehabilitation: Randomised controlled trials. http://hstat.nlm.nih.gov/ Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2001): Heart, stroke and vascular diseases: Australian Facts 2001. www.heartfoundation.com.au/statistic Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2000): Physical activity patterns of Australian adults. www.aihw.gov.au/publications/health/papaa/index.html Chisholm D, Ashwell S, Flower D, Hazel J, Jenkins A, ODea K & Zimmett P (1994): Diabetes and exercise: Series on diabetes No.4 www.health.gov.au/nhmrc/publications/fullhtml/di5.htm Henry L (2002): Dealing with Diabetes. Muscle and Fitness www.fitnessonline.com health>illness>specific diseases>article Mathers C, Vos T & Stevenson C (1999): Burden of disease and injury in Australia. AIHW Cat No. PHE 17 Canberra:AIHW National Cardiac Rehabilitation Advisory Committee (NCRAC) of the National Heart Foundation of Australia (2000): Recommendations for Cardiac Rehabilitation www.heartfoundation.com.au/prof/04_recom_rehab.html Pulmonary Rehabilitation Services Ohio State University Medical Centre (2001): Health for life: Pulmonary Rehabilitation Program Activity Guidelines http://www.acs.ohio-state.edu/units/osuhosp/patedu/ homedocs.pdf/discond.pdf/respirat.pdf/act-guide.pdf Ries A, Carlin B, Carrieri-Kohlman V, Casaburi R, Celli B, Emery C, Hodgkin J, Mahler D, Make B & Skolnick J (1997): Pulmonary Rehabilitation: Evidence-Based Guidelines. Chest 112: pp 136396 www.chestnet/health.science.policy/quick.reference.guides/pulmrehab.qrg.html Rockville (MD) (1995): Cardiac Rehabilitation: Evidence-based guidelines. US Department of Health and Human services, Public Health Services, AHCPR. October; p 202 http://www.guidelines.gov/index.asp Shilton T, Abernethy P, Atkinson R, Bauman A, Brown W, Naughton G, Oldenburg B, Owen N & Wright C (2001): Promoting physical activity Ten recommendations from the Heart Foundation www.heartfoundation.com.au/ prof/docs/promo_physi_act.htm Swanson N (1999): The Northern Territory Experience: Background to the Preventable Chronic Disease Strategy). Aboriginal Health Strategy Unit Territory Health Services Taylor A (2002): Physical Activity: Another resource in the arsenal in fighting hypertension. Get Active 1(3): p 4. The national centre on physical activity and disability (NCPAD) (2000): General Exercise Guidelines www.ncpad.org Walsh W (2001): Cardiovascular Health in Indigenous Australians: a call for action. The Medical Journal of Australia 175: pp 3512. Whedon B & Dobbins K (2000): Get fit now- Ask me how www.worldfitness.org/program.html

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Low Copper Diet For Wilson's DiseaseDocument4 pagesLow Copper Diet For Wilson's DiseaseFayasulhusain MuthalibNo ratings yet

- Cerc 2014edition PDFDocument462 pagesCerc 2014edition PDFMMontes100% (1)

- The Krisiloff Anti-Inflammatory Diet RevolutionDocument3 pagesThe Krisiloff Anti-Inflammatory Diet Revolutiongethealthybooks0% (2)

- Oman New Health Application FormDocument3 pagesOman New Health Application FormAravind AlavantharNo ratings yet

- The Clinical and Scientific Basis of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/ Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Byron M. Hyde, M.D.Document753 pagesThe Clinical and Scientific Basis of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/ Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Byron M. Hyde, M.D.Gènia100% (2)

- UIAMS Summer Training Project PDFDocument65 pagesUIAMS Summer Training Project PDFShreeya Sharma0% (1)

- What Can We Learn From ICT Users in EnglDocument13 pagesWhat Can We Learn From ICT Users in EnglFayasulhusain MuthalibNo ratings yet

- 3D Mask Template See Kate Sew PDFDocument2 pages3D Mask Template See Kate Sew PDFFayasulhusain MuthalibNo ratings yet

- Donu Donu Donu Maari Lyrics TamilDocument2 pagesDonu Donu Donu Maari Lyrics TamilFayasulhusain MuthalibNo ratings yet

- Role of ICT in English Language TeachingDocument1 pageRole of ICT in English Language TeachingFayasulhusain MuthalibNo ratings yet

- Kannae Kalai Mane Viswasam LyricsDocument2 pagesKannae Kalai Mane Viswasam LyricsFayasulhusain Muthalib100% (1)

- Akkam PakkamDocument1 pageAkkam PakkamFayasulhusain MuthalibNo ratings yet

- Ayayayo PudichirukkuDocument1 pageAyayayo PudichirukkuFayasulhusain MuthalibNo ratings yet

- Dish TVDocument1 pageDish TVFayasulhusain MuthalibNo ratings yet

- Alaporan TamilanDocument2 pagesAlaporan TamilanFayasulhusain MuthalibNo ratings yet

- Neethane NeethaneDocument1 pageNeethane NeethaneFayasulhusain MuthalibNo ratings yet

- Grief and Loss: Author: DR Ofra FriedDocument3 pagesGrief and Loss: Author: DR Ofra FriedFayasulhusain MuthalibNo ratings yet

- Neighbour - The Inner ConsultationDocument1 pageNeighbour - The Inner ConsultationFayasulhusain MuthalibNo ratings yet

- SLMA Ordinaly and Life MembershipDocument1 pageSLMA Ordinaly and Life MembershipFayasulhusain MuthalibNo ratings yet

- Application Form Opening Account RevisedV1 210814Document4 pagesApplication Form Opening Account RevisedV1 210814Fayasulhusain Muthalib0% (1)

- DR Pallab Saha - EA & Public HealthDocument24 pagesDR Pallab Saha - EA & Public HealthDave SenNo ratings yet

- Master of Nursing CurriculumDocument10 pagesMaster of Nursing CurriculumArief YantoNo ratings yet

- A Good Life To The End Sample ChapterDocument29 pagesA Good Life To The End Sample ChapterAllen & Unwin100% (1)

- 10.1007@s10916 019 1489 9Document10 pages10.1007@s10916 019 1489 9Vikas SharmaNo ratings yet

- Neural Therapy With Bee-VenomDocument2 pagesNeural Therapy With Bee-Venomrobert039No ratings yet

- Healthyonify and Healthy Plus Merge To Create "PlusOnify"Document3 pagesHealthyonify and Healthy Plus Merge To Create "PlusOnify"PR.comNo ratings yet

- NSFAS Disability Annexure A - 2023Document2 pagesNSFAS Disability Annexure A - 2023karabo karaboNo ratings yet

- New NANDA Nursing DiagnosesDocument7 pagesNew NANDA Nursing DiagnosesGaela Leniel NocidalNo ratings yet

- Course OutlineDocument19 pagesCourse OutlinecydeykulgmzarinlhkNo ratings yet

- Rubinstein2015 Mhealth PreHTADocument12 pagesRubinstein2015 Mhealth PreHTACristian PeñaNo ratings yet

- Principles and Concepts of Behavioral Medicine 2018Document1,132 pagesPrinciples and Concepts of Behavioral Medicine 2018Koliber CR100% (1)

- Intravenous Blood Laser Therapy and Cardivascular StudiesDocument43 pagesIntravenous Blood Laser Therapy and Cardivascular StudiesRodrigo Ribeiro de CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Final DraftDocument21 pagesLiterature Review Final DraftJared AugensteinNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 - Lifestyle Diseases and ManagementDocument46 pagesLesson 2 - Lifestyle Diseases and ManagementAlessaNo ratings yet

- Fast Hug in Bed PleaseDocument7 pagesFast Hug in Bed PleaseGuillermo Obando LaraNo ratings yet

- Writing Assignment IIIDocument2 pagesWriting Assignment IIIStefy Ortiz BdvNo ratings yet

- Stepping Stones ClubHouse May 2011Document16 pagesStepping Stones ClubHouse May 2011Sharon A StockerNo ratings yet

- Quality in Family Practice Book of ToolsDocument207 pagesQuality in Family Practice Book of ToolsAmanda LimNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion PolicyDocument12 pagesHealth Promotion PolicyLalita A/P AnbarasenNo ratings yet

- Care of The Older AdultDocument55 pagesCare of The Older AdultJohan Maloloy-onNo ratings yet

- 11 PhysicalEducationDocument144 pages11 PhysicalEducationRavi RajNo ratings yet

- DLL - May 8-12Document21 pagesDLL - May 8-12Arnold ArceoNo ratings yet

- Roy ModelDocument3 pagesRoy Modelkhaldoon aiedNo ratings yet

- Chronic Pain ManagementDocument44 pagesChronic Pain ManagementTomBramboNo ratings yet

- The Macro-Social Environment and HealthDocument17 pagesThe Macro-Social Environment and HealthSophia JohnsonNo ratings yet