Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Discuss The Role of Women in Early Modern Europe

Uploaded by

AssignmentLab.comOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Discuss The Role of Women in Early Modern Europe

Uploaded by

AssignmentLab.comCopyright:

Available Formats

Clients Last Name Goes Here 1 Discuss the Role of Women in Early Modern Europe

Before starting this topic we would like to determine the limits of the early modern history. Approximately it started in 1450s and ended in1850s. During this lengthy period a lot of transformations occurred: the Reformation, the decline of the feudal system and the growth of commerce, and the invention or application of such potentially powerful innovations as paper, printing, the mariners compass, and gunpowder.1 And all of that made its impact on womens role in society. But what was the real life of a common woman of that period? What rights did they enjoyed or were deprived of? Were there any differences in comparison with their aristocratic counterparts? First of all, we should make it clear that it was common to consider a woman as a creature unequal to a man. Such attitude was connected with the Catholic belief that a man is superior to a woman. On the other hand, the Reformation brought about some changes: They (Protestants) emphasized too that men and women were spiritual equals who should be companionate partners for each other as spouses. Protestant reliance on the Bible as the guide to Christian faith stimulated the education of women as well as men.2 Moreover, marriageable girls were sometimes characterised as merchandize.3 It was a common practise to hire a marriage broker in order to find a suitable spouse, preferably from an honoured family and with a big dowry:

Renaissance. Encyclopedia Britannica Online Teresa Meade, and Merry Wiesner-Hanks. A Companion to Gender History. (Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004), 349. 3 Gene Brucker. Giovanni and Lusanna. Love and Marriage in Renaissance Florence (University of California Press, 1986), 107.

2

Clients Last Name Goes Here 2 So important was the ideal of feminine chastity to family honour that it was guarded as jealously by male relatives as was their property. A stain upon a familys reputation adversely affected its social standing and, specifically, its ability to contract good marriages for its daughters.4 In general, females were regarded as only temporary members of either their birth families or the families of their husbands.5 That is why parents tried to find a beneficial marriage partner for their daughter(s) and were willing to give large dowries (1000 to 2000 florins and more) so that their daughters could marry honorably6. But in most cases the practice of dowries had other pragmatic reasons, which had nothing in common with parental care: Families used dowries to fulfill but at the same time limit their obligation to daughters while sons shared in equal (and usually larger) shares of all remaining propertyWomen brought dowries that were either gifts from their parents or the accumulated savings of their own earnings, especially as domestic servants. These dowries included both cash sums and the essential goods needed to set up a new household a bed, some linen, some pots and pans. 7 It must be emphasized that the consequences of such injustice were terrible: many Florentine widows, who were dependant on charity, lived as pensioners in religious houses or were forced to work as servants (and sometimes concubines) in the households of merchants and priests8. In other words, women were almost certainly doomed to become someones mistress

4 5

Brucker, Giovanni, 78. Meade, and Wiesner-Hanks, A Companion, 344. 6 Brucker, Giovanni, 10. 7 Meade, and Wiesner-Hanks, A Companion, 344-345. 8 Brucker, Giovanni, 90.

Clients Last Name Goes Here 3 or to enter a convent as a boarder or to join one of the tertiary religious houses where they performed charitable services9. Was everything so bad for women? Was it a vicious circle? In Italy, asylums for women at risk (whether from prostitution, marital difficulty, widowhood or poverty) were established that combined practical help in offering shelter and teaching basic skills with large doses of religious and moral education. 10 As can be observed there were not too many options for women. But what about upper-class women, did they have similar problems? According to Gene Brucker: Women from the artisanal class enjoyed a greater degree of social freedom than did their chaperoned, aristocratic sisters. They could move freely in the streets, gossip with neighbors, shop in the markets, attend services in their local church. Some worked in their husbands botteghe or, if widowed, as independent shopkeepers or spinners or weavers in the citys cloth industry.11 Apparently, aristocratic sisters did not enjoy even that amount of freedom, but thanks to the importance of familys honor, they had a bit more safety and protection. And what about judiciary system? How did it help common women to protect their rights? It would be proper to start with the notion that the pursuit of women was a common pastime of young males of all classes, but particularly among the rich and wellborn12. According to Brucker: Giovanni della Casa (aristocrat) would have incurred censure only if he had seduced an unmarried girl from a respectable family or had violated a nun. But even such

Brucker, Giovanni, 120. Meade, and Wiesner-Hanks, A Companion, 351. 11 Brucker, Giovanni, 91. 12 Ibid., 77.

10

Clients Last Name Goes Here 4 peccadilloes could be forgiven.13And at courts women could only be represented by their legal guardians.14They couldnt defend their rights on their own. Despite all of that, those were the times when the western European marriage pattern 15 emerged: Marriage patterns were distinctive, with most men marrying in their late twenties or later and women in their late teens. Studies of Florence and Venice have shown that with men spending years as adults before marrying, prostitution was common and homosexual relations were a widely accepted phase of life for men. Italian elites were careful to safeguard the safety and chastity of women of their own class, but had little regard for elite mens exploitation of lower-class women whether through rape or casual fornication.16 In Renaissance Florence and in Europe generally, the sentiment of love and the institution of marriage were rarely combined into the felicitous state that later became the Western ideal, if not often the reality.17 If compare traditions of present society and that of the period in question, a lot of differences and even absurdity can be encountered. For example, Gene Brucker in his Giovanni and Lusanna provides us with a particular unwritten rule of early modern society: She stared openly at men whom she encountered in the streets, a violation of the social convention which decreed that respectable women should lower their gaze in public.18

13 14

Brucker, Giovanni, 80. Ibid., 94. 15 David Herlihy. Aspects of Early Modern Society. Encyclopedia Britannica Online 16 Meade, and Wiesner-Hanks, A Companion, 344. 17 Brucker, Giovanni, 93. 18 Ibid., 27.

Clients Last Name Goes Here 5 As a conclusion, we would like to emphasize that even if some social or lawful guarantees existed at all, they were totally neglected with the help of money and powerful connections. If we are to scrutinise the story of Giovanni and Lusanna (by Gene Brucker) we would find a bitter disappointment and resentment. Let us not forget that Lusanna was a middle-class woman and daughters of artisans did not marry the sons of aristocratic families19 in order to avoid such troubles. Although Lusanna won the ecclesiastical court in Florence, the Roman curia ruled that their marriage (with Giovanni) was null and void.20Therefore, all her efforts to restore her reputation were in vain. And women from the upper-class were not in much better situation, because they could not choose their spouse independently and their parents used them to increase their own profits and influence.

19 20

Ibid., 95. Brucker, Giovanni, 118.

Clients Last Name Goes Here 6

Bibliography

Brucker, Gene. Giovanni and Lusanna. Love and Marriage in Renaissance Florence. University of California Press, 1986. Accessed Sep. 19, 2012, http://www.ebookdb.org/iread.php?id=5312G423G0G722327D3D1E69 Herlihy, David. Aspects of early modern society. Encyclopedia Britannica Online, accessed Sep. 17, 2012, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/195896/history-ofEurope/58342/Aspects-of-early-modern-society Meade, Teresa, and Wiesner-Hanks, Merry. A Companion to Gender History. Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004. Accessed Sep. 18, 2012, http://wxy.seu.edu.cn/humanities/sociology/htmledit/uploadfile/system/20100501/201005 01152318995.pdf Renaissance. Encyclopedia Britannica Online, accessed Sep. 19, 2012, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/497731/Renaissance

You might also like

- COOK, MATT - A New City of Friends. London and Homosexuality in The 1890sDocument27 pagesCOOK, MATT - A New City of Friends. London and Homosexuality in The 1890sDaniel Santos JiménezNo ratings yet

- Marriage in The Victorian EraDocument2 pagesMarriage in The Victorian EraPatricia Ciobică0% (1)

- Marriage, Sex, and Civic Culture in Late Medieval LondonFrom EverandMarriage, Sex, and Civic Culture in Late Medieval LondonRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Neighbours and strangers: Local societies in early medieval EuropeFrom EverandNeighbours and strangers: Local societies in early medieval EuropeNo ratings yet

- Scandal: The Sexual Politics of the British ConstitutionFrom EverandScandal: The Sexual Politics of the British ConstitutionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Regulating homosexuality in Soviet Russia, 1956–91: A different historyFrom EverandRegulating homosexuality in Soviet Russia, 1956–91: A different historyNo ratings yet

- Heathcliff As FemaleDocument1 pageHeathcliff As FemaleSteely92No ratings yet

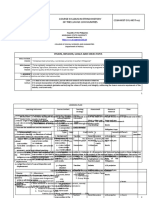

- IAE Assessment SheetsDocument5 pagesIAE Assessment SheetsSaneil Rite-off CamoNo ratings yet

- Lev Vygotsky: Vygotsky's Theory Differs From That of Piaget in A Number of Important WaysDocument9 pagesLev Vygotsky: Vygotsky's Theory Differs From That of Piaget in A Number of Important WaysDiana Diana100% (1)

- Foundation Myths in Ancient Societies: Dialogues and DiscoursesFrom EverandFoundation Myths in Ancient Societies: Dialogues and DiscoursesNo ratings yet

- Secrets & Scandals in Regency Britain: Sex, Drugs & Proxy RuleFrom EverandSecrets & Scandals in Regency Britain: Sex, Drugs & Proxy RuleRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Nikolaus Dumba (1830-1900): A Dazzling Figure in Imperial ViennaFrom EverandNikolaus Dumba (1830-1900): A Dazzling Figure in Imperial ViennaNo ratings yet

- “My World My Work My Woman All My Own” Reading Dante Gabriel Rossetti in His Visual and Textual NarrativesFrom Everand“My World My Work My Woman All My Own” Reading Dante Gabriel Rossetti in His Visual and Textual NarrativesNo ratings yet

- Genre Structure and Poetics in The Byzantine Vernacular Romances of Love. The Symbolae Osloenses DebateDocument96 pagesGenre Structure and Poetics in The Byzantine Vernacular Romances of Love. The Symbolae Osloenses DebateByzantine Philology100% (1)

- Microhistory and The Histories of Everyday Life: Cultural and Social HistoryDocument24 pagesMicrohistory and The Histories of Everyday Life: Cultural and Social HistoryfiraNo ratings yet

- Leadbeater Behrendt Series Posted June 08 Final FinalDocument15 pagesLeadbeater Behrendt Series Posted June 08 Final Finalmulvihill3100% (1)

- NHD The English Alewives A Triumph in Trade Bred Tragic DownfallDocument23 pagesNHD The English Alewives A Triumph in Trade Bred Tragic Downfallapi-540435180No ratings yet

- Affective medievalism: Love, abjection and discontentFrom EverandAffective medievalism: Love, abjection and discontentNo ratings yet

- Rebel Without Borders: Frontline Missions in Africa and the GulfFrom EverandRebel Without Borders: Frontline Missions in Africa and the GulfRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1)

- The Life of a Medical Officer in WWI: The Experiences of Captain Harry Gordon ParkerFrom EverandThe Life of a Medical Officer in WWI: The Experiences of Captain Harry Gordon ParkerNo ratings yet

- Struggle and Suffrage in Southend-on-Sea: Women's Lives and the Fight for EqualityFrom EverandStruggle and Suffrage in Southend-on-Sea: Women's Lives and the Fight for EqualityNo ratings yet

- Matthäus SchwarzDocument23 pagesMatthäus SchwarzBia EleonoraNo ratings yet

- On Lesbian and Gay - Queer Medieval Studies PDFDocument4 pagesOn Lesbian and Gay - Queer Medieval Studies PDFPilar Espitia DuránNo ratings yet

- Palaces of Revolution: Life, Death and Art at the Stuart CourtFrom EverandPalaces of Revolution: Life, Death and Art at the Stuart CourtNo ratings yet

- The Writing Public: Participatory Knowledge Production in Enlightenment and Revolutionary FranceFrom EverandThe Writing Public: Participatory Knowledge Production in Enlightenment and Revolutionary FranceNo ratings yet

- Voices of the Georgian Age: 100 Remarkable Years, In Their Own WordsFrom EverandVoices of the Georgian Age: 100 Remarkable Years, In Their Own WordsNo ratings yet

- England's Social Upheaval After the Black DeathDocument34 pagesEngland's Social Upheaval After the Black DeathJoel HarrisonNo ratings yet

- Victorian Sensation: The Extraordinary Publication, Reception, and Secret Authorship of Vestiges of the Natural History of CreationFrom EverandVictorian Sensation: The Extraordinary Publication, Reception, and Secret Authorship of Vestiges of the Natural History of CreationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- The Virtues of Economy: Governance, Power, and Piety in Late Medieval RomeFrom EverandThe Virtues of Economy: Governance, Power, and Piety in Late Medieval RomeNo ratings yet

- Whose Wales?: The battle for Welsh devolution and nationhood, 1880-2020From EverandWhose Wales?: The battle for Welsh devolution and nationhood, 1880-2020No ratings yet

- A Tour of Two Cities: 18th Century London and Paris ComparedFrom EverandA Tour of Two Cities: 18th Century London and Paris ComparedNo ratings yet

- The "Ladies of Llangollen" as Sketched by Many Hands; with Notices of Other Objects of Interest in "That Sweetest of Vales"From EverandThe "Ladies of Llangollen" as Sketched by Many Hands; with Notices of Other Objects of Interest in "That Sweetest of Vales"No ratings yet

- Clarissa's Ciphers: Meaning and Disruption in Richardson's ClarissaFrom EverandClarissa's Ciphers: Meaning and Disruption in Richardson's ClarissaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Introduction To The New Man, Masculinity and Marriage in The Victorian NovelDocument23 pagesIntroduction To The New Man, Masculinity and Marriage in The Victorian NovelPickering and Chatto100% (1)

- Struggle and Suffrage in Windsor: Women's Lives and the Fight for EqualityFrom EverandStruggle and Suffrage in Windsor: Women's Lives and the Fight for EqualityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Pursuit of HappinessDocument4 pagesThe Pursuit of HappinessAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Promise by C. Wright MillsDocument4 pagesThe Promise by C. Wright MillsAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Origin of My NameDocument4 pagesThe Origin of My NameAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Old Testament Law and Its Fulfillment in ChristDocument7 pagesThe Old Testament Law and Its Fulfillment in ChristAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Principal-Agent ProblemDocument9 pagesThe Principal-Agent ProblemAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Most Dangerous Moment Comes With VictoryDocument3 pagesThe Most Dangerous Moment Comes With VictoryAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Polygraph and Lie DetectionDocument4 pagesThe Polygraph and Lie DetectionAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Problem of Consequences and ForgivenessDocument4 pagesThe Problem of Consequences and ForgivenessAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Principle of AutonomyDocument2 pagesThe Principle of AutonomyAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Place of Endangered Languages in A Global SocietyDocument3 pagesThe Place of Endangered Languages in A Global SocietyAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The One Minute ManagerDocument2 pagesThe One Minute ManagerAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Opinion Essay On The Short Story "Seventh Grade" by Gary SotoDocument2 pagesThe Opinion Essay On The Short Story "Seventh Grade" by Gary SotoAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Models of Church "As A Communion" and "As A Political Society" TheDocument7 pagesThe Models of Church "As A Communion" and "As A Political Society" TheAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Obscurities of Blue Collar Jobs and Sociological Factors Affecting Blue CollarDocument7 pagesThe Obscurities of Blue Collar Jobs and Sociological Factors Affecting Blue CollarAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The MetamorphosisDocument4 pagesThe MetamorphosisAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Microsoft CaseDocument3 pagesThe Microsoft CaseAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Merchant of VeniceDocument5 pagesThe Merchant of VeniceAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Mini Mental Status ExaminationDocument4 pagesThe Mini Mental Status ExaminationAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Media and The GovernmentDocument4 pagesThe Media and The GovernmentAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Marketing Mix 2 Promotion and Price CS3Document5 pagesThe Marketing Mix 2 Promotion and Price CS3AssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Issues Surrounding The Coding of SoftwareDocument10 pagesThe Issues Surrounding The Coding of SoftwareAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Lorax On Easter IslandDocument4 pagesThe Lorax On Easter IslandAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Impact of The Depression of The 1890s On Political Tensions of The TimeDocument3 pagesThe Impact of The Depression of The 1890s On Political Tensions of The TimeAssignmentLab.com100% (1)

- The Life StyleDocument3 pagesThe Life StyleAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Families On Children's SchoolDocument8 pagesThe Influence of Families On Children's SchoolAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Human Hand in Global WarmingDocument10 pagesThe Human Hand in Global WarmingAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The LawDocument4 pagesThe LawAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Implications On Mobile Commerce in The International Marketing CommunicationDocument2 pagesThe Implications On Mobile Commerce in The International Marketing CommunicationAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Media On Illicit Drug UseDocument6 pagesThe Impact of Media On Illicit Drug UseAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- The Identity of Christianity Given by Early ArtDocument6 pagesThe Identity of Christianity Given by Early ArtAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- Teaching Students With Fetal Alcohol Spectrum DisorderDocument182 pagesTeaching Students With Fetal Alcohol Spectrum DisorderJChesedNo ratings yet

- King Lear Story of An AlbionDocument21 pagesKing Lear Story of An Albiontaib1No ratings yet

- General Assembly Narrative ReportDocument4 pagesGeneral Assembly Narrative Reportritz manzanoNo ratings yet

- Developing reading skills in a competence-based curriculumDocument6 pagesDeveloping reading skills in a competence-based curriculumAna Marie Bayabay SeniningNo ratings yet

- EquusDocument4 pagesEquusapi-269228441No ratings yet

- Grammar+HW-parallelism ADocument2 pagesGrammar+HW-parallelism Avijayendra koritalaNo ratings yet

- Understanding the Causes and Risk Factors of Child DefilementDocument6 pagesUnderstanding the Causes and Risk Factors of Child Defilementcrutagonya391No ratings yet

- The Influence of Christianity on SocietyDocument4 pagesThe Influence of Christianity on Societyikkiboy21No ratings yet

- REFORMS Zulfiqar AliDocument3 pagesREFORMS Zulfiqar AliHealth ClubNo ratings yet

- Governing The Female Body - Gender - Health - and Networks of Power PDFDocument323 pagesGoverning The Female Body - Gender - Health - and Networks of Power PDFMarian Siciliano0% (1)

- Importance of Economics in School CurriculumDocument11 pagesImportance of Economics in School CurriculumJayeeta Adhya100% (2)

- Types of GovernmentDocument7 pagesTypes of GovernmentJscovitchNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Template: GCU College of EducationDocument5 pagesLesson Plan Template: GCU College of Educationapi-434634172No ratings yet

- Compound Interest CalculatorDocument4 pagesCompound Interest CalculatorYvonne Alonzo De BelenNo ratings yet

- Problems Related To Global Media CulturesDocument3 pagesProblems Related To Global Media CulturesJacque Landrito ZurbitoNo ratings yet

- Note: "Sign" Means Word + Concept Wedded Together.Document2 pagesNote: "Sign" Means Word + Concept Wedded Together.Oscar HuachoArroyoNo ratings yet

- Learn To Speak Spanish - Learn Spanish - Rocket Spanish!Document22 pagesLearn To Speak Spanish - Learn Spanish - Rocket Spanish!Philippe PopulaireNo ratings yet

- 5 LANGAUGES in CONTEMPORARY WORLDDocument69 pages5 LANGAUGES in CONTEMPORARY WORLDPatrickXavierNo ratings yet

- Spatial Locations: Carol DelaneyDocument17 pagesSpatial Locations: Carol DelaneySNo ratings yet

- Definition of EI PDFDocument13 pagesDefinition of EI PDFPhani KumarNo ratings yet

- Class Struggle and Womens Liberation PDFDocument305 pagesClass Struggle and Womens Liberation PDFAsklepios AesculapiusNo ratings yet

- The Last Lesson by Alphonse DaudetDocument11 pagesThe Last Lesson by Alphonse DaudetalishaNo ratings yet

- The Use of Pixar Animated Movies To Improve The Speaking Skill in The EFL ClassroomDocument9 pagesThe Use of Pixar Animated Movies To Improve The Speaking Skill in The EFL ClassroomjohnaconchaNo ratings yet

- Philosophy ReviewerChapter 3 and 5Document9 pagesPhilosophy ReviewerChapter 3 and 5Kise RyotaNo ratings yet

- 12 Angry MenDocument20 pages12 Angry MenKetoki MazumdarNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Hist. 107 StudentDocument6 pagesSyllabus Hist. 107 StudentloidaNo ratings yet

- AFRICANS IN ARABIA FELIX: AKSUMITE RELATIONS WITH ḤIMYAR IN THE SIXTH CENTURY C.E. Vol. I George Hatke PHDDocument463 pagesAFRICANS IN ARABIA FELIX: AKSUMITE RELATIONS WITH ḤIMYAR IN THE SIXTH CENTURY C.E. Vol. I George Hatke PHDAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-Misri100% (2)

- ICSI CSR Brochure PDFDocument4 pagesICSI CSR Brochure PDFratnaNo ratings yet