Professional Documents

Culture Documents

G

Uploaded by

Zie BeaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

G

Uploaded by

Zie BeaCopyright:

Available Formats

G.R. No.

57092 January 21, 1993 EDGARDO DE JESUS, REMEDIOS DE JESUS, JUANITO DE JESUS, JULIANA DE JESUS, JOSE DE JESUS, FLORDELIZA DE JESUS, REYNALDO DE JESUS, ERNESTO DE JESUS, PRISCILO DE JESUS, CORAZON DE JESUS, Petitioners, vs. COURT OF APPEALS and PRIMITIVA FELIPE DE JESUS, Respondents. FACTS: The property in dispute is a parcel of residential land situated in Bulacan, in the name of Victoriano Felipe. Private respondent executed a sworn statement declaring herself the only heir of the deceased Victoriano Felipe and adjudicating to herself the ownership of the land. Petitioners herein filed in the Court of First Instance of Bulacan, an action for recovery of ownership and possession and quieting of title to the land covered by a Tax Declaration, alleging that their grandfather, Santiago de Jesus during his lifetime owned the residential lot; and when he died, the land was succeeded by the petitioners. The trial court, in its judgment, declared petitioners as having the better right to ownership and possession of the land. However, the Court of Appeals set aside such decision. Hence, the instant petition for review. ISSUE: WON the petitioners have the right to the ownership and possession of the land by virtue of hereditary succession, or private respondent who claims ownership through purchase of the property by her parents. HELD: The court held that petitioners the right to the ownership and possession of the land in question. In the case, it appears that Victoriano Felipe was residing in the house of Santiago de Jesus simply because of his spouse. In effect, their possession of the contested lot was neither exclusive nor in the concept of owner. Possession, to constitute the foundation of a prescriptive right, must be possession under a claim of title or it must be adverse or in the concept of owner or concepto de dueo. Victoriano Felipe and his family were residing in the land by mere tolerance. Moreover, the "Kasulatang-Biling-Mabibiling-Muli" was not even given to private respondent by her parents; she admitted having found it in the house although they mentioned its existence to her when they were still alive. Petitioners presented as evidence, a certified true copy of Tax Declarations of the land. On the other hand, private respondent could not present such document which shattered the presumption of validity of the contract of sale with right to repurchase. G.R. No. L-29838. March 18, 1983.] FERMIN BOBIS and EMILIA GUADALUPE, Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. THE PROVINCIAL SHERIFF OF CAMARINES NORTE and ZOSIMO RIVERA, Defendants-Appellees. FACTS: Rufina Camino and Pastor Eco were the registered owners of a parcel of land, covered which was cultivated by the spouses Fermin Bobis and Emilia Guadalupe. Alfonso Ortega filed a complaint against Rufina Camino, Pastor Eco, Emilia Guadalupe, and Fermin Bobis with the Court of First Instance of Camarines Norte, for the recovery of possession of one-half (1/2) of the land. In view of this, the parties executed a compromise agreement whereby they agreed to pay the plaintiff the sum of P140.00, as full payment for all the improvements in the land in question, payable on February 28, 1951. The defendants Rufina Camino and Pastor Eco, however, only paid the amount of P50.00 to Alfonso Ortega when the obligation became due on February 28, 1951. As a result, a writ of execution was issued, commanding the Provincial Sheriff of Camarines Norte that the goods and chattels of the defendants Rufina Camino, Pastor Eco, Emilia Guadalupe, and Fermin Bobis be caused to be made the sum of P140.00. Upon learning of the levy on execution, Emilia Guadalupe and Fermin Bobis filed a motion seeking the modification of the writ of execution to exclude them therefrom because under the judgment sought to be executed only the defendants Rufina Camino and Pastor Eco were obligated to pay the plaintiff Alfonso Ortega. But, the trial court denied the motion. ISSUE: WON the writ of execution is null and void with respect to its effect to the spouses petitioners. HELD: YES. The writ of execution is null and void and of no legal effect with respect to the spouses petitioners. In the case, only Rufina Camino and Pastor Eco were adjudged to pay Alfonso Ortega the amount of P140.00 on February 28, 1951. Although petitioners were included as party defendants, they were not ordered to pay Alfonso Ortega. Obviously, they were absolved from liability. Accordingly, as to them, there was nothing to execute since they have been absolved from liability.

In the Rules of Court, the writ of execution must conform to the judgment which is to be executed, as it may not vary the terms of the judgment it seeks to enforce; nor may it go beyond the terms of the judgment sought to be executed. Where the execution is not in harmony with the judgment which gives it life and exceeds it, it has pro tanto no validity. To maintain otherwise would be to ignore the constitutional provision against depriving a person of his property without due process of law. G.R. No. L-48747 September 30, 1982 ANGEL JEREOS, petitioner, vs. HON. COURT OF APPEALS, SOLEDAD RODRIGUEZ, FELICIA R. REYES, JOSE RODRIGUEZ, JESUS RODRIGUEZ, Jr., ROBERTO RODRIGUEZ, FRANCISCO RODRIGUEZ, TERESITA RODRIGUEZ, MANUEL RODRIGUEZ, ANTONIO RODRIGUEZ, DOMINGO PARDORLA, Jr., and NARCISO JARAVILLA, respondents. FACTS: Private respondent, Domingo Pardorla, Jr. is the holder of a certificate of public convenience for the operation of a jeepney line in Iloilo City. One of his jeepneys, driven by Narciso Jaravilla, hit Judge Jesus S. Rodriguez and his wife, Soledad, causing injuries to them, which resulted in the death of Judge Rodriguez. Thereafter, Soledad Rodriguez and her children filed with the Court of First Instance of Iloilo an action for damages against Narciso Jaravilla, Domingo Pardorla, Jr., and Angel Jereos, the actual owner of the jeepney. Angel Jereos denied ownership of the jeepney in question and claimed that the plaintiffs have no cause of action against him. After appropriate proceedings, the Court of First Instance of Iloilo rendered judgment ordering Narciso Jaravilla and Doming Pardorla, Jr. to pay, jointly and severally, damages to the plaintiffs. Angel Jereos was exonerated for the reason that the Court found no credible evidence to support plaintiffs' as well as defendant Pardorla's contention that defendant Jereos was the operator of the passenger jeepney in question at the time of the accident happened. Both plaintiffs and the defendants Narciso Jaravilla and Domingo Pardorla, Jr., appealed to the Court of Appeals. The plaintiffs contended that the trial court erred in not finding the defendant Angel Jereos jointly and severally liable with the their defendants for the damages incurred by them. The Court of Appeals rendered a decision, modifying the decision of the trial court, and holding that Angel Jereos is jointly and severally liable with the other defendants for the damages awarded by the trial court to the plaintiffs. Hence, petitioner appealed from the decision. ISSUE: WON the petitioner is jointly and severally liable with the defendants for damages to plaintiffs. HELD: YES. The petitioner is jointly and severally liable with the defendants for awarding damages to plaintiffs. While the Court therein ruled that the registered owner or operator of a passenger vehicle is jointly and severally liable with the driver of the said vehicle for damages incurred by passengers or third persons as a consequence of injuries or death sustained in the operation of the said vehicle, the Court did so to correct the erroneous findings of the Court of Appeals that the liability of the registered owner or operator of a passenger vehicle is merely subsidiary, as contemplated in Art. 103 of the Revised Penal Code. In no case did the Court exempt the actual owner of the passenger vehicle from liability. Among others, that the registered owner or operator has the right to be indemnified by the real or actual owner of the amount that he may be required to pay as damage for the injury caused. The right to be indemnified being recognized, recovery by the registered owner or operator may be made in any form-either by a cross-claim, third-party complaint, or an independent action. G.R. No. 158131 August 8, 2007

SOCIAL SECURITY SYSTEM, petitioner, vs. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, JOSE V. MARTEL, OLGA S. MARTEL, and SYSTEMS AND ENCODING CORPORATION, respondents. FACTS: Petitioner is a government-owned and controlled corporation mandated by its charter, RA 1161, to provide financial benefits to private sector employees. SENCOR is covered by RA 1161, as amended by RA 8282, Section 22 of which requires employers like SENCOR to remit monthly contributions to petitioner representing the share of the employer and its employees.

Petitioner filed with the Pasay City Prosecutors Office a complaint against respondent Martels and their five co-accused for SENCORs nonpayment of contributions. To pay this amount, respondent Martels offered to assign to petitioner a parcel of land in Tagaytay City. Petitioner accepted the offer subject to the condition that respondent Martels will settle their obligation either by way of dacion en pago or through cash settlement within a reasonable time. Thus, petitioner withdrew its complaint from the Pasay City Prosecutors Office but reserved its right to revive the same in the event that no settlement is arrived at. Respondent Martel wrote petitioner offering, in lieu of the Tagaytay City property, computer-related services. Petitioner then filed with the Pasay City Prosecutors Office another complaint against respondent Martels and their five co-accused for SENCORs non-remittance of contributions. In their counter-affidavit, respondent Martels and their co-accused alleged that petitioner is estopped from holding them criminally liable since petitioner had accepted their offer to assign the Tagaytay City property as payment of SENCORs liability. Thus, according to the accused, the relationship between SENCOR and petitioner was converted into an ordinary debtor-creditor relationship through novation. Prosecutor Artemio Puti found probable cause to indict respondent Martels for violation of Section 22(a) and (b) in relation to Section 28(e) of RA 1161, as amended by RA 8282 and rejected their claim of negation of criminal liability by novation, holding that (1) SENCORs criminal liability was already consummated before respondent Martels offered to pay SENCORs liability and (2) the dacion en pago involving the Tagaytay City property did not materialize. Respondent Martels appealed to the DOJ. The DOJ granted respondent Martels appeal and found that respondent and petitioner entered into a compromise agreement before the filing of the Information in Criminal Case and such negated any criminal liability on the part of the respondents. ISSUE: WON the concept of novation serves to abate the prosecution of respondent s for violation of Section 22(a) and (b) in relation to Section 28(e) of RA 1161, as amended. HELD: NO. The concept of novation finds no application in the case at bar. Novation, a civil law concept relating to the modification of obligations, takes place when the parties to an existing contract execute a new contract which either changes the object or principal condition of the original contract, substitutes the person of the debtor, or subrogates a third person in the rights of the creditor. The effect is either to modify or extinguish the original contract. In its extinctive form, the new obligation replaces the original, extinguishing the obligors obligations under the old contract. In the case, between SENCOR and petitioner, no original contract that can be replaced by a new contract changing the object or principal condition of the original contract, substituting the person of the debtor, or subrogating a third person in the rights of the creditor. The original relationship between SENCOR and petitioner is defined by law RA 1161, as amended which requires employers like SENCOR to make periodic contributions to petitioner under pain of criminal prosecution. Unless Congress enacts a law further amending RA 1161 to give employers a chance to settle their overdue contributions to prevent prosecution, no amount of agreements between petitioner and SENCOR can change the nature of their relationship and the consequence of SENCORs non-payment of contributions. The novation theory may perhaps apply prior to the filing of the criminal information in court by the state prosecutors because up to that time the original trust relation may be converted by the parties into an ordinary creditor-debtor situation, thereby placing the complainant in estoppel to insist on the original trust. But after the justice authorities have taken cognizance of the crime and instituted action in court, the offended party may no longer divest the prosecution of its power to exact the criminal liability, as distinguished from the civil. The crime being an offense against the state, only the latter can renounce it. It may be observed in this regard that novation is not one of the means recognized by the Penal Code whereby criminal liability can be extinguished; hence, the role of novation may be to prevent the rise of criminal liability . Moreover, there should a prior contractual relation G.R. No. 123793. June 29, 1998 ASSOCIATED BANK, petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS and LORENZO SARMIENTO JR., respondents. FACTS: The Associated Banking Corporation and Citizens Bank and Trust Company merged to form just one banking corporation known as Associated Citizens Bank, the surviving bank. The Associated Citizens Bank changed its corporate name to Associated Bank by virtue of the Amended Articles of Incorporation. The defendant executed in favor of Associated Bank a promissory note whereby the former undertook to pay the latter on or before March 6, 1978. However, despite repeated demands the defendant failed to pay the amount due. He then denied all the pertinent allegations in the complaint.

Based on the evidence presented by petitioner, the trial court ordered Respondent Sarmiento to pay the bank his remaining balance plus interests and attorneys fees. ISSUE: WON Associated Bank, the surviving corporation, may enforce the promissory note made by private respondent in favor of CBTC, the absorbed company, after the merger agreement had been signed. HELD: The Associated Bank assumedall rights of CBTC. Ordinarily, in the merger of two or more existing corporations, one of the combining corporations survives and continues the combined business, while the rest are dissolved and all their rights, properties and liabilities are acquired by the surviving corporation. Although there is a dissolution of the absorbed corporations, there is no winding up of their affairs or liquidation of their assets, because the surviving corporation automatically acquires all their rights, privileges and powers, as well as their liabilities. The merger, however, does not become effective upon the mere agreement of the constituent corporations. The procedure to be followed is prescribed under the Corporation Code. Section 79 of said Code requires the approval by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) of the articles of merger which, in turn, must have been duly approved by a majority of the respective stockholders of the constituent corporations. The records do not show when the SEC approved the merger. Private respondents theory is that it took effect on the date of the execution of the agreement itself, which was September 16, 1975. Private respondent contends that, since he issued the promissory note to CBTC on September 7, 1977 -- two years after the merger agreement had been executed -- CBTC could not have conveyed or transferred to petitioner its interest in the said note, which was not yet in existence at the time of the merger. Therefore, petitioner, the surviving bank, has no right to enforce the promissory note on private respondent; such right properly pertains only to CBTC. Assuming that the effectivity date of the merger was the date of its execution, we still cannot agree that petitioner no longer has any interest in the promissory note. Thus, the fact that the promissory note was executed after the effectivity date of the merger does not militate against petitioner. The agreement itself clearly provides that allcontracts -- irrespective of the date of execution -- entered into in the name of CBTC shall be understood as pertaining to the surviving bank, herein petitioner. Since, in contrast to the earlier aforequoted provision, the latter clause no longer specifically refers only to contracts existing at the time of the merger, no distinction should be made. The clause must have been deliberately included in the agreement in order to protect the interests of the combining banks; specifically, to avoid giving the merger agreement a farcical interpretation aimed at evading fulfillment of a due obligation. Thus, although the subject promissory note names CBTC as the payee, the reference to CBTC in the note shall be construed, under the very provisions of the merger agreement, as a reference to petitioner bank, as if such reference *was a+ direct reference to the latter for all intents and purposes. In light of the foregoing, the Court holds that petitioner has a valid cause of action against private respondent. Clearly, the failure of private respondent to honor his obligation under the promissory note constitutes a violation of petitioners right to collect the pro ceeds of the loan it extended to the former. No Contract Pour Autrui Private respondent, while not denying that he executed the promissory note in the amount of P2,500,000 in favor of CBTC, offers the alternative defense that said note was a contract pour autrui. A stipulation pour autrui is one in favor of a third person who may demand its fulfillment, provided he communicated his acceptance to the obligor before its revocation. An incidental benefit or interest, which another person gains, is not sufficient. The contracting parties must have clearly and deliberately conferred a favor upon a third person. The requisites for such contract: (1) the stipulation in favor of a third person must be a part of the contract, and not the contract itself; (2) the favorable stipulation should not be conditioned or compensated by any kind of obligation; and (3) neither of the contracting parties bears the legal representation or authorization of the third party. The fairest test in determining whether the third persons inter est in a contract is a stipulation pour autrui or merely an incidental interest is to examine the intention of the parties as disclosed by their contract. We carefully and thoroughly perused the promissory note, but found no stipulation at all that would even resemble a provision in consideration of a third person. The instrument itself does not disclose the purpose of the loan contract. It merely lays down the terms of payment and the penalties incurred for failure to pay upon maturity. It is patently devoid of any indication that a benefit or interest was thereby created in favor of a person other than the contracting parties. In fact, in no part of the instrument is there any mention of a third party at all. Except for his

barefaced statement, no evidence was proffered by private respondent to support his argument. Accordingly, his contention cannot be sustained. At any rate, if indeed the loan actually benefited a third person who undertook to repay the bank, private respondent could have availed himself of the legal remedy of a third-party complaint. That he made no effort to implead such third person proves the hollowness of his arguments. G.R. No. L-55739 June 22, 1984 CARLO LEZAMA BUNDALIAN and JOSE R. BUNDALIAN, petitioners, vs. THE HON. COURT OF APPEALS, JUANITO LITTAWA and EDNA CAMCAM, respondents. FACTS: The petitioners purchased from the Estate of the Deceased Agapita Sarao Vda. de Virata parcels of land. The following day, the petitioners, in a contract denominated as Deed of Sale with Right to Repurchase, sold to the private respondents the land under specified terms and conditions. One of the terms and conditions was that the repurchase price would escalate month after month, depending on when repurchase would be effected. It was also stipulated in the same contract that the vendor shall have the right to possess, use, and build on, the property during the period pending redemption. The petitioners filed a petition for declaratory relief and/or reformation of instrument before the Court of First Instance of Rizal to declare the Deed of Sale with Right to Repurchase an equitable mortgage and the entire portion of the same deed referring to the accelerating repurchase price null and void for being usurious. The private respondents, in turn, filed a petition for the consolidation of ownership on the ground that more than a year has elapsed since the execution of the Deed of Sale with Right to Repurchase by the vendor. The private respondents contended that notwithstanding which the vendor has failed to avail of its rights under the provisions of Article 1607 in relation to Article 1616 of the New Civil Code, the vendor has lost all his rights to avail himself of the right to consolidate ownership of the property subject of the Deed of Sale. ISSUE: RESPONDENT COURT OF APPEALS ERRED GRAVELY TO THE EXTENT OF GRVE ABUSE OF DISCREATION, IN NOT REVERSING THE APPEALED JUDGMENT AND GRANTING THE PRAYERS OF PETITIONERS-APPELLANTS, FOREMOST OF WHICH IS TO DECLARE THE DEED OF SALE WITH RIGHT TO REPURCHASE TO BE AN EQUITABLE MORTGAGE. Tell issue is this case is whether or not the deed of sale with right to repurchase should be declared as an equitable mortgage. We find meritorious the petitioners' contention that under Article 1602 of the Civil Code the deed of sale with right to repurchase should be presumed to be an equitable mortgage due to the following reasons. (1) The contracts involving the subject properties came one after another in the space of two (2) days. The Deed of Absolute Sale between petitioner Jose R. Bundalian as vendee and Romeo S. Geluz, in his capacity as Administratorf of the Estate of the deceased Agapita Sarao Vda. de Virata, as vendor, was executed on July 1, 1975 (pp. 19-26, Annex "A"). The purported Deed of Sale with Right to Repurchase between petitioner, Jose R. Bundalian as vendor and respondents Juanito Littawa and Edna Camcam as vendees was executed on July 2, 1975 (pp. 2632, Annex "A").lwphl@it This already indicates, at a very early stage, that the two transactions must be intimately related. (2) Such intimate relation between the aforementioned Deed of Absolute Sale and Deed of Sale with Right to Repurchase is already clear in the statement in the latter instrument that the subject property had just been purchased by Jose R. Bundalian from the estate of the deceased Agapita Sarao Vda. de Virata, 'with funds loaned to him by the herein VENDEES' the latter being no other than respondents Littawa and Camcam (p. 28, Annex "A"). Patently, petitioner Jose R. Bundalian was funded by private respondents to enable him to purchase the property from the said estate. (3) Having just purchased the property from the estate by way of Deed of Absolute Sale on July 1, 1975, for which he had just paid P499,200.00 as purchase price, it would have been utterly senseless for petitioner Jose R. Bundalian to sell the same property to private respondents the very next day, July 2, 1975, with or without the right of repurchase. No other conclusion is possible except that the Deed of Sale with Right to Repurchase is precisely the security the equitable mortgage to petitioner Jose R. Bundalian to enable the latter to purchase the property from the aforementioned estate. (4) It would have been more senseless for petitioner Jose R. Bundalian to sell the property to private respondents at the same price of P499,200.00 he had paid the estate of the deceased Agapita Sarao Vda. de Virata, without profit and at a sure loss. By the terms of the Deed of Sale with Right to Repurchase he would have to repurchase the property at a continually increasing price, from Pl 50.00 per square meter to P190.00 per square meter, that is, up to P133,120.00 over and above the original price of P499,200.00, in only four (4) months. Again, no other conclusion is possible but that the contract is an equitable mortgage, not a sale.

(5) It is provided in the Deed of Sale with Right to Repurchase that 'It is agreed that the vendor (Jose R. Bundalian) shall have the right to possess, use, and build on, the property during the period of redemption' (p. 30, Annex "A"). It has been held that there is a 'loan with security' rather than a pacto de retro sale where by agreement the vendor was to remain in possession of the lands (Escoto vs. Arcilla, 89 Phil. 199, 204). Where there was an acknowledgment of the vendor's right to retain possession of the property, as in the case at bar, the contract was one of "loan guaranteed by a mortgage" rather than a conditional sale (Macoy vs. Trinidad, 95 Phil. 192, 202). Indeed, there can be no question that petitioner Jose R. Bundalian remained legally in possession of the subject property. Again, the conclusion is ineluctable that the Deed of Sale with Right to Repurchase was executed as security for the loan extended by private respondents to petitioner Jose R. Bundalian, i.e., as equitable mortgage. (6) The increase per month in the alleged redemption price is very compatible with the Idea that the transaction was really intended by the parties to be a mortgage. It bears emphasis, at this juncture, that the supposed repurchase price is in the same amount as the original "price" of P499,200.00 should "repurchase" be effected during the first month from and after the date of the instrument; P532,480.00 computed at P160.00 per square meter should "repurchase" be effected after the first month; P565,760.00 computed at P170.00 per square meter should "repurchase" be after the second month; P599,040.00 computed at P180.00 per square meter should "repurchase" be after the third month; or P632,320.00 computed at P190.00 per square meter should "repurchase" be effected even "after the fourth month" (pp. 29-30, Annex "A"). The monthly increases in the alleged "redemption price"clearly represent nothing but interest. It is well-settled that provision for interest payments is a clear indication that the supposed sale is actually an equitable mortgage (Macoy vs. Trinidad, 95 Phil. 192, 202; Escoto vs. Arcilla, 89 Phil. 199, 204). This would fall under the legal situation "where it may be fairly inferred that the real intention of the parties is that the transaction shall secure the payment of a debt or the performance of any other obligation" (No. 6), Art. 1062, Civil Code). To make matters worse, the monthly increase in the supposed "redemption price", meaning the interest of course, are clearly usurious, precisely one of the evils sought to be negated by the provisions of Articles 1602, 1603 and 1604 of the Civil Code, as noted previously herein. (7) While the Deed of Sale with Right to Repurchase supposedly provided for a "redemption" period of "four (4) months from and after the date of this instrument" (p. 29, Annex "A"), it later necessarily provided for a built-in extension of the period of 'redemption' by providing for payment of the amount of P632,320.00 computed at P190.00 per square meter should "repurchase" be effected "after the fourth month" (p. 30, Annex "A"). In other words, it was implicitly agreed that the period of 'repurchase' was not limited to 4 months from and after the date of execution of the instrument, in as much as said "repurchase" could be effected even "after the fourth month". It is well settled that extension of the period of "redemption" is indicative of equitable mortgage (Nos.(3) and (6), Art. 1602, Civil Code; Reyes vs. De Leon, 20 SCRA 369, 370). (8) It may be argued, as private respondents have argued, that normally a loan does not exceed 60% of the price of the land given as security, so that private respondents could not have loaned P499,200.00 on the land the value of which was claimed to be also P499,200.00. However, such reasoning is clearly unsound. It loses sight of the fact that private respondents precisely funded or financed petitioner Jose R. Bundalian's acquisition of the property from the estate of the deceased Agapita Sarao Vda. de Virata. In other words, petitioner Jose R. Bundalian could not have acquired the land to serve as security for the repayment of the loan unless private respondents had extended the loan in the first place. Surely, private respondents stood to benefit enormously from such financing transaction in view of the patently usurious monthly interests transparently disguised as the accelerating or increasing monthly 'repurchase' price. At any rate, in the event that petitioner Jose R. Bundalian ultimately failed to pay the loan, the rapid increase in the price of the land, which was estimated to be worth at least P632,320.00 after 4 months (from the initial P499,200.00), practically guaranteed a very good return on the money investment of private respondents as moneylenders. (9) It cannot be questioned that petitioner Jose R. Bundalian paid taxes on the land, even after the supposed 4 month period of "redemption". Payment of taxes after expiration of the supposed "redemption" period has been considered as indicative of equitable mortgage (Escoto vs. Arcilla,supra). (10) It is an admitted fact that private respondents took some time before filing their petition for consolidation of ownership. Private respondents admitted in said petition that "more than a year has elapsed since the execution of the Deed of Sale with Right to Repurchase" (p. 34, par. 3, Annex "A"). Reckoning 4 months from July 2, 1975, it would appear that the "repurchase" period expired supposedly on November 2, 1975. As private respondents filed their petition for consolidation on August 27, 1976, it is clear that they delayed filing said petition by more than 9 months. A similar delay in the filing of the supposed "vendee's" petition for consolidation was considered as indicative of equitable mortgage (Reyes vs. de Leon, 20 SCRA 369, 378). (11) If the Deed of Sale with Right to Repurchase would not be considered as an equitable mortgage, it would result that there was actually no security for the loan of P499,200.00 extended by private respondents to petitioners Jose R. Bundalian, which would make no sense at all considering the enormity of the loan. There was, to be sure, a security for said loan, none other than the equitable mortgage tainted with usury and disguised as the Deed of Sale with Right to Repurchase. The private respondents argued that the petitioners' contention is true only in cases where the contract or instrument is not reflective of the true intentions of the contracting parties as would warrant reformation of the same. They stated that if the intention of the parties is to execute a deed of sale with pacto de retro, the contract should be held as such. The petitioners were allegedly fully aware that the deed of sale with pacto de retro is what it purports to be and nothing else. Furthermore, the petitioners waited for the period of redemption to expire before availing of the relief granted by the Civil Code of reformation of contracts. We find the stand of the private respondents without merit. The intent of the parties to circumvent the provision discouraging pacto de retro transactions is very apparent from the records. Article 1602 of the Civil Code states:

Article 1602. The contract shall be presumed to be an equitable mortgage, in any of the following cases: (1) When the price of a sale with right to repurchase is unusually inadequate; (2) When the vendor remains in possession as lessee or otherwise; (3) When upon or after the expiration of the right to repurchase another instrument extending the period of redemption or granting a new period is executed; (4) When the purchaser retains for himself a part of the purchase price; (5) When the vendor binds himself to pay the taxes on the thing sold; (6) In any other eases where it may be fairly inferred that the real intention of the parties is that the transaction shall secure the payment of a debt or performance of any other obligation. In any of the foregoing cases, any money, fruits, or other benefit to be received by the vendee as rent or otherwise shall be considered as interest which shall be subject to the usury laws. Significantly, a portion of the document in question reads: (The vendor) having just purchased the same from the Intestate estate of the deceased Agapita Sarao Vda. de Virata (Special Proceedings No. B-710 of the Court of First Instance of Cavite), with funds loaned to him by the herein VENDEES. (Emphasis supplied). This statement appearing in the supposed pacto de retro sale confirms the real intention of the parties to secure the payment of the loan acquired by the petitioners from the private respondents. The sale with the right to repurchase of the three parcels of land was for P499,200.00, which was exactly the same amount paid to the estate of the deceased Agapita Sarao Vda. de Virata- After having purchased the three lots for P499,200.00, the vendors should at least have earned a little profit or interest if they really intended to resell the lots the following day. Instead, they suffered a loss of P25,000.00 because the amount borrowed, and we find grounds to believe their statement of having advanced P25,000.00 of their own funds as earnest money, was actually only P474,000.00. The petitioners also bound themselves to pay exceedingly stiff prices for the privilege of repurchase. The intent of the parties is further shown by the fact that the Bundalians P500,000.00 collectibles due from the government for completed construction contracts could not be collected on time to pay for the lots advertised for sale in Bulletin Today. The petitioners had to run to the private respondents who had money to lend. The Bundalians received the accounts due from the government only in 1977 after the proceedings in the trial court were well underway. The stipulation in the contract sharply escalating the repurchase price every month enhances the presumption that the transaction is an equitable mortgage. Its purpose is to secure the return of the money invested with substantial profit or interest, a common characteristic of loans. The private respondents try to capitalize on an admission by Mrs. Bundalian that she "accepted" the transaction knowing it to be a contract of sale with right of repurchase. The reliance is grounded on shaky foundations. The Bundalians were in the construction business and knew quite well what they were signing. But vendors covered by Article 1602 of the Civil Code are usually in no position to bargain with the vendees and will sign onerous contracts to get the money they need. It is precisely this evil which the Civil Code guards against. It is not the knowledge of the vendors that they are executing a contract of sale pacto de retro which is the issue but whether or not the real contract was one of sale or a loan disguised as a pacto de retro sale. The contract also provides that "it is agreed that the vendor shall have the right to possess, use, and build on, the property during the period of redemption." When the vendee acknowledged the right of the vendor to retain possession of the property the contract is one of loan guaranteed by mortgage, not a conditional sale or an option to repurchase. (Macoy vs. Trinidad, et al., 95 Phil. 192). The respondents' contention that the right to possess, use, or build on the lots embodied in the contract was a mere "right" and not actual possession appears to be sophistry. The records show that the Bundalians construction equipment such as tractors, payloaders, and bulldozers were on the lots. A shop was built on the premises. Mr. Bundalian testified that from the time he purchased the property from the estate of Mrs. Virata up to the "minute" he testified, he never lost possession. The Bundalians paid the real estate taxes on the lots. As against the express provision of the contract and the actual possession by the petitioners, the private respondents come up with a far fetched argument that since the titles to the lots were in their hands, they were the ones in legal possession. Parenthetically, the titles in their hands were still in the name of the estate of Agapita Sarao Vda. de Virata, the original vendor-owner. The deed of sale with right to repurchase is declared as an equitable mortgage. The petitioners are ordered to pay their debt to the private respondents with legal rate of interest from the time they acquired the loan until it is fully paid. G.R. No. 122053. May 15, 1998 RUPERTO PUREZA, petitioner, vs. THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS, ASIA TRUST DEVELOPMENT BANK and SPOUSES BONIFACIO AND CRISANTA ALEJANDRO, respondents.

FACTS: Respondent spouses Bonifacio and Crisanta Alejandro are building contractors conducting business under the name of Boncris Trading and Builders. Petitioner Ruperto Pureza sought their services in the construction of a two-story houseTo facilitate this project, he applied for a PagIbig Housing Loan with the Asia Trust Development Bank. This arrangement was embodied in a Construction Agreement entered into by the parties, with the net proceeds of the loan. The construction of the house was commenced but not terminated. Before the completion of the project, the spouses Alejandro informed petitioner that certain finishing works must be cancelled to reduce costs. Petitioner acceded with certain conditions, one of which was the signing of an Order of Payment specifying therein the staggered amounts of the loan to be released by the Bank to the spouses. Petitioner (as plaintiff) filed an action for Specific Performance and damages before the Regional Trial Court of Makati, to prevent respondent (defendant therein) Asia Trust Development Bank from collecting the loan or foreclosing the mortgage on plaintiff's house and lot. He claimed that although the construction was only seventy percent (70%) finished, the Bank had released to the spouses ninety percent (90%) of the proceeds of the loan. In their answer, the defendant spouses alleged that the plaintiff and his wife Myrna authorized the release of the proceeds of the loan on a staggered basis, in accordance with the Order of Payment. They further state that, the plaintiff having signed a Certificate of House Completion/Acceptance, the Bank was likewise authorized to turn the loan over to the Pag-Ibig Housing as creditor. The lower court rendered a decision in favor of plaintiff, ordering defendant Bank to pay 28% of the net proceeds of the loan which it was found to have negligently delivered to defendant spouses. The spouses were, in turn, ordered to reimburse the Bank the said amount. Petitioner asserts that the Court of Appeals erred in finding that the respondent Bank was neither negligent nor careless in releasing the proceeds of the loan to the spouses, in accordance with the Order of Payment. He relies on the findings of the lower court, as evidenced by the ocular inspection, that the construction of the house had not yet been completed nor was it executed in accordance with his wishes. This being so, he claims that respondent Bank and respondent spouses are jointly and severally liable for the costs of repair, moral and exemplary damages, attorney's fees and the costs of suit. ISSUE: WON HELD: This petition holds no scintilla of merit. A study of respondent court's decision shows that while it gave credence to the ocular inspection, it also took into consideration the other evidence presented by respondents, which petitioner neither denied nor disputed. In fact, petitioner explicitly admitted the genuineness and due execution of the Order of Payment in the proceedings before the lower court. Having found that petitioner willingly and voluntarily signed the Order[12] and the Certificate of House Completion/Acceptance,[13] it ruled correctly in holding that the release of funds to respondent spouses in staggered amounts was done according to the instructions of petitioner and in compliance with the said Certificate. No further conditions were imposed by him to restrict the authority granted to the Bank insofar as the discharge of funds is concerned. Clearly, an attempt is made by petitioner to escape his pecuniary obligations by subsequently repudiating documents he had earlier executed, if only to avoid or delay payment of his monthly amortizations. The application of the principle of estoppel is proper and timely in heading off petitioner's shrewd efforts at renouncing his previous acts to the prejudice of parties who had dealt with him honestly and in good faith. A principle of equity and natural justice, this is expressly adopted under Article 1431 of the Civil Code, and pronounced as one of the conclusive presumptions under Rule 131, Section 3(a) of the Rules of Court, as follows: "Whenever a party has, by his own declaration, act or omission, intentionally and deliberately led another to believe a particular thing to be true, and to act upon such a belief he cannot, in any litigation arising out of such declaration, act or omission, be permitted to falsify it."[14] Petitioner, having performed affirmative acts upon which the respondents based their subsequent actions, cannot thereafter refute his acts or renege on the effects of the same, to the prejudice of the latter. To allow him to do so would be tantamount to conferring upon him the liberty to limit his liability at his whim and caprice, which is against the very principles of equity and natural justice as abovestated. Respondent Bank and respondent spouses cannot be held jointly and solidarily liable for the costs of repair, moral and exemplary damages, attorney's fees and the costs of suit. The findings of the lower court that respondent Bank recklessly and negligently released the proceeds of the loan to the spouses were not supported by evidence. The Bank did nothing but fulfill its undertakings under the loan agreement in accordance with petitioner's instructions. It cannot be charged for any damage caused upon the house of petitioner even if such damage may be attributable to the spouses. If, indeed, repairs were necessary to improve the physical condition of the house, respondent Bank not being the contractor thereof, cannot be held jointly and severally liable with the spouses.

You might also like

- GSIS Vs Court of AppealsDocument1 pageGSIS Vs Court of AppealsJanice M. PolinarNo ratings yet

- Alvarez v. IACDocument3 pagesAlvarez v. IACJustin MoretoNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Rodolfo Crisostomo v. Rudex Intl Development Corporation G.R. No. 176129Document10 pagesHeirs of Rodolfo Crisostomo v. Rudex Intl Development Corporation G.R. No. 176129nette PagulayanNo ratings yet

- Heirs of T. de Leon Vda de Roxas v. CADocument3 pagesHeirs of T. de Leon Vda de Roxas v. CALeo TumaganNo ratings yet

- Flores vs. Mallare-PhillippsDocument8 pagesFlores vs. Mallare-PhillippsJo Marie SantosNo ratings yet

- Alvarado vs. Gaviola Jr.Document8 pagesAlvarado vs. Gaviola Jr.Dexter CircaNo ratings yet

- 2018 Specpro CasesDocument6 pages2018 Specpro CasesKen AliudinNo ratings yet

- Alvarez vs. IacDocument1 pageAlvarez vs. IacAlljun SerenadoNo ratings yet

- Makati Leasing and Finance Corp. vs. Wearever Textile Mills, Inc. 122 Scra 296Document5 pagesMakati Leasing and Finance Corp. vs. Wearever Textile Mills, Inc. 122 Scra 296Apple Ke-eNo ratings yet

- Agrarian CasesDocument42 pagesAgrarian CasesKnarf MidsNo ratings yet

- Olizon vs. CA GR 107075 Sept. 1, 1994 Case DigestDocument2 pagesOlizon vs. CA GR 107075 Sept. 1, 1994 Case Digestbeingme2No ratings yet

- 06 Hernaez v. HernaezDocument1 page06 Hernaez v. HernaezKenny EspiNo ratings yet

- Dais V GardunoDocument2 pagesDais V GardunoamberspanktowerNo ratings yet

- Bautista vs. BautistaDocument7 pagesBautista vs. BautistaSarahNo ratings yet

- TSN EstateDocument19 pagesTSN EstateGrace EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Director of Lands V CADocument3 pagesDirector of Lands V CAMicah Clark-MalinaoNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Restar v. Heirs of Cichon, 475 SCRA 731Document4 pagesHeirs of Restar v. Heirs of Cichon, 475 SCRA 731Angelette BulacanNo ratings yet

- GR 204926 Dec 4 2014Document10 pagesGR 204926 Dec 4 2014Frederick EboñaNo ratings yet

- 01 CD Special ProceedingsDocument7 pages01 CD Special ProceedingsRmLyn MclnaoNo ratings yet

- Civpro CasesDocument147 pagesCivpro CasesRose Ann CalanglangNo ratings yet

- Balus V BalusDocument2 pagesBalus V BalusLuis PerezNo ratings yet

- Virgilio B. Aguilar v. CA & Senen B. Aguilar FactsDocument2 pagesVirgilio B. Aguilar v. CA & Senen B. Aguilar FactsSocNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Guido Vs Del RosarioDocument1 pageHeirs of Guido Vs Del Rosariocarol anneNo ratings yet

- 44 Vda de Quirino Vs PalarcaDocument1 page44 Vda de Quirino Vs PalarcaRyanMacadangdangNo ratings yet

- Lacson Vs Executive Secretary - BanicoDocument2 pagesLacson Vs Executive Secretary - BanicoWendy PeñafielNo ratings yet

- Merida V People DigestDocument5 pagesMerida V People DigestJoshua LanzonNo ratings yet

- Felipe vs. Heirs of AldonDocument1 pageFelipe vs. Heirs of AldonJesse Dela Cruz LunzagaNo ratings yet

- Romualdez Et. Al. v. Tiglao Et. Al. 105 SCRA 762 (1981)Document45 pagesRomualdez Et. Al. v. Tiglao Et. Al. 105 SCRA 762 (1981)Janz SerranoNo ratings yet

- in Re Estate of The Deceased Gregorio Tolentino - WillsDocument2 pagesin Re Estate of The Deceased Gregorio Tolentino - WillsAndrea TiuNo ratings yet

- Balus vs. BalusDocument3 pagesBalus vs. BalusprincessF0717No ratings yet

- Union Bank Vs Edmund SantibanezDocument3 pagesUnion Bank Vs Edmund SantibanezReycy Ruth TrivinoNo ratings yet

- Del Rosario v. Lucena GR NO. L-3546 Sep 13, 1907 PDFDocument5 pagesDel Rosario v. Lucena GR NO. L-3546 Sep 13, 1907 PDFShane FulguerasNo ratings yet

- DOCTRINE: Unlike Holographic Wills, Ordinary Wills May Be ProvedDocument2 pagesDOCTRINE: Unlike Holographic Wills, Ordinary Wills May Be ProvedMaveeNo ratings yet

- Republic Vs IACDocument3 pagesRepublic Vs IACcarloNo ratings yet

- 269-Republic v. Patanao G.R. No. L-22356 July 21, 1967Document3 pages269-Republic v. Patanao G.R. No. L-22356 July 21, 1967Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Leandro Natividad v. Mauricio-NatividadDocument10 pagesHeirs of Leandro Natividad v. Mauricio-NatividadPhulagyn CañedoNo ratings yet

- Mun Tangkal CaseDocument3 pagesMun Tangkal CaseAngelo John M. ValienteNo ratings yet

- Rioferio Vs CADocument3 pagesRioferio Vs CAKenmar NoganNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Malabanan V Republic PropertyDocument8 pagesHeirs of Malabanan V Republic Propertyᜉᜂᜎᜊᜒᜀᜃ ᜎᜓᜌᜓᜎNo ratings yet

- Fenequito Vs Vergara, Jr. G.R. No. 172829, July 8, 2012 FactsDocument4 pagesFenequito Vs Vergara, Jr. G.R. No. 172829, July 8, 2012 FactsLoveAnneNo ratings yet

- Estacion Vs BernardoDocument20 pagesEstacion Vs BernardoMelissa AdajarNo ratings yet

- De Leon Vs CA-1Document1 pageDe Leon Vs CA-1Mc BagualNo ratings yet

- Digest Cases Settlement of EstateDocument4 pagesDigest Cases Settlement of EstateTerry FordNo ratings yet

- GR No 155733Document1 pageGR No 155733Robin Cunanan100% (1)

- Bacaling V Laguna GR No. L-26694Document5 pagesBacaling V Laguna GR No. L-26694dynsimonetteNo ratings yet

- Imperial vs. ArmesDocument17 pagesImperial vs. ArmesWorstWitch Tala0% (1)

- Digests AgainDocument5 pagesDigests AgainGieldan BulalacaoNo ratings yet

- Co-v.-Rosario-et.-al.-576-Phil.-223-2008Document2 pagesCo-v.-Rosario-et.-al.-576-Phil.-223-2008Jemson Ivan WalcienNo ratings yet

- EvidenceDocument156 pagesEvidenceJade Palace TribezNo ratings yet

- Air France v. CarrascosoDocument21 pagesAir France v. CarrascosoNadine Reyna CantosNo ratings yet

- Yujuico Vs United ResourcesDocument3 pagesYujuico Vs United ResourcesGeorginaNo ratings yet

- Samson v. Quintin, G.R. No. 19142, (March 5, 1923), 44 PHIL 573-576)Document3 pagesSamson v. Quintin, G.R. No. 19142, (March 5, 1923), 44 PHIL 573-576)yasuren2No ratings yet

- Admin Recit 2Document2 pagesAdmin Recit 2Bazel GueseNo ratings yet

- Unisource Commercial and Development Corp. Vs Joseph Chung, Et. Al. - GR No. 173252 - July 17, 2009Document3 pagesUnisource Commercial and Development Corp. Vs Joseph Chung, Et. Al. - GR No. 173252 - July 17, 2009BerniceAnneAseñas-ElmacoNo ratings yet

- Victory Liner Vs GammadDocument5 pagesVictory Liner Vs GammadCherry BepitelNo ratings yet

- Anderson Vs PerkinsDocument5 pagesAnderson Vs Perkinsdiamajolu gaygonsNo ratings yet

- Dalay vs. Aquiatin, Credit TransactionsDocument2 pagesDalay vs. Aquiatin, Credit TransactionsGemma F. TiamaNo ratings yet

- Delos Reyes Vs SolidumDocument2 pagesDelos Reyes Vs SolidumElyn ApiadoNo ratings yet

- 089 Ramnani VsDocument2 pages089 Ramnani VsJacob DalisayNo ratings yet

- ATP No. 86-92 Case DigestsDocument9 pagesATP No. 86-92 Case DigestsKenneth AvalonNo ratings yet

- Craft Stitches Needle Thread Textile Arts Paleolithic Spinning Weaving Fabric Archaeologists Europe Fur Skin Clothing Bone Antler Ivory Sinew Catgut VeinsDocument2 pagesCraft Stitches Needle Thread Textile Arts Paleolithic Spinning Weaving Fabric Archaeologists Europe Fur Skin Clothing Bone Antler Ivory Sinew Catgut VeinsZie BeaNo ratings yet

- Corruption in The GovernmentDocument2 pagesCorruption in The GovernmentZie BeaNo ratings yet

- Building Block Model From Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia: Dual-Purpose BreedDocument3 pagesBuilding Block Model From Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia: Dual-Purpose BreedZie BeaNo ratings yet

- What Is CyberbullyingDocument3 pagesWhat Is CyberbullyingZie BeaNo ratings yet

- MahabharataDocument3 pagesMahabharataZie BeaNo ratings yet

- Mga Ahensya Sa Ilalim NG Sangay Na TagapagpaganapDocument5 pagesMga Ahensya Sa Ilalim NG Sangay Na TagapagpaganapZie Bea100% (1)

- PhysicsDocument6 pagesPhysicsZie BeaNo ratings yet

- How To Introduce YourselfDocument5 pagesHow To Introduce YourselfZie BeaNo ratings yet

- Joyster Manpower Services IncDocument1 pageJoyster Manpower Services IncZie BeaNo ratings yet

- Baked Cheesy Eggplant Recipe: IngredieDocument2 pagesBaked Cheesy Eggplant Recipe: IngredieZie BeaNo ratings yet

- Coron Festival: Lubid Festival in Malilipot, AlbayDocument1 pageCoron Festival: Lubid Festival in Malilipot, AlbayZie BeaNo ratings yet

- Pears: Planting in ContainersDocument3 pagesPears: Planting in ContainersZie BeaNo ratings yet

- IrregularDocument1 pageIrregularZie BeaNo ratings yet

- EmmanDocument4 pagesEmmanZie BeaNo ratings yet

- Cha Cha: 2. FoxtrotDocument2 pagesCha Cha: 2. FoxtrotZie BeaNo ratings yet

- Planting LakatanDocument5 pagesPlanting LakatanZie Bea100% (2)

- Pears: Planting in ContainersDocument3 pagesPears: Planting in ContainersZie BeaNo ratings yet

- Tabak Festival in Tabaco CityDocument2 pagesTabak Festival in Tabaco CityZie BeaNo ratings yet

- Solar System PlanetsDocument1 pageSolar System PlanetsZie BeaNo ratings yet

- Scientific Names. 1.: SpeedDocument3 pagesScientific Names. 1.: SpeedZie BeaNo ratings yet

- Career Objectives:: Alden B. BermasDocument2 pagesCareer Objectives:: Alden B. BermasZie BeaNo ratings yet

- JoyceDocument1 pageJoyceZie BeaNo ratings yet

- PP ArrrrDocument5 pagesPP ArrrrZie BeaNo ratings yet

- PPPPPPPPPPDocument12 pagesPPPPPPPPPPZie BeaNo ratings yet

- Va)Document4 pagesVa)Zie BeaNo ratings yet

- March 28, 2015: Administrative and Supervisory StaffDocument9 pagesMarch 28, 2015: Administrative and Supervisory StaffZie BeaNo ratings yet

- Lion Man of Hohlenstein StadelDocument3 pagesLion Man of Hohlenstein StadelZie BeaNo ratings yet

- SCHOOL AGE (6-11 Years Old)Document12 pagesSCHOOL AGE (6-11 Years Old)Zie BeaNo ratings yet

- Human Development Prenatal StageDocument2 pagesHuman Development Prenatal StageZie BeaNo ratings yet

- Wage Theory, Portion of Economic Theory That Attempts To Explain The Determination ofDocument1 pageWage Theory, Portion of Economic Theory That Attempts To Explain The Determination ofZie BeaNo ratings yet

- Montgomery V Etreppid # 1086 - Montgomery DeclarationDocument6 pagesMontgomery V Etreppid # 1086 - Montgomery DeclarationJack RyanNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Financial Management: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinDocument22 pagesIntroduction To Financial Management: Mcgraw-Hill/Irwinsenthilkumar99No ratings yet

- Magdalena Estates Inc Vs RodriguezDocument1 pageMagdalena Estates Inc Vs RodriguezCass ParkNo ratings yet

- Letter of AuthorizationDocument1 pageLetter of AuthorizationGabriel de VeraNo ratings yet

- Bank Branch Audit ManualDocument55 pagesBank Branch Audit ManualNeeraj Goyal100% (1)

- Lakshwiz Bazaar - Marketing Case Study Challenge.Document3 pagesLakshwiz Bazaar - Marketing Case Study Challenge.Dushyant Singh SolankiNo ratings yet

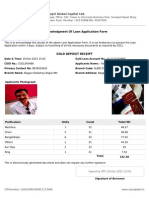

- Acknowledgment of Loan Application Form: Capri Global Capital LTDDocument9 pagesAcknowledgment of Loan Application Form: Capri Global Capital LTDRahul MahankalNo ratings yet

- Import Export ManagementDocument130 pagesImport Export ManagementNishita ShahNo ratings yet

- Pocket Money: Name: Jaime Loh Jie Yu I/C Number: 000528-06-0408 Name of Group Members: 1. Jacelyn Chong Jia ErnDocument18 pagesPocket Money: Name: Jaime Loh Jie Yu I/C Number: 000528-06-0408 Name of Group Members: 1. Jacelyn Chong Jia Ernwey weyNo ratings yet

- Contributions Payment Form: Social Security SystemDocument6 pagesContributions Payment Form: Social Security SystemAttyGalva22No ratings yet

- Falin-Math of Finance and Investment 3 PDFDocument97 pagesFalin-Math of Finance and Investment 3 PDFAlfred alegadoNo ratings yet

- Housing by People, Towards Autonomy in Building Environments - John F. C. Turner PDFDocument205 pagesHousing by People, Towards Autonomy in Building Environments - John F. C. Turner PDFffarq90No ratings yet

- Home Loan AllDocument3 pagesHome Loan Allsumanpal78No ratings yet

- Cashflow STMT of Honda MotorsDocument22 pagesCashflow STMT of Honda Motorsmir musaweer aliNo ratings yet

- Personal Loan Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesPersonal Loan Literature Reviewc5qx9hq5100% (2)

- Beverly Complaint - Bank of AmericaDocument158 pagesBeverly Complaint - Bank of Americajmaglich1No ratings yet

- Money Matters VocabularyDocument16 pagesMoney Matters VocabularySvetlana TselishchevaNo ratings yet

- CF AssignmentDocument112 pagesCF AssignmentAbhijit DileepNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment in Bop ProjectsDocument22 pagesRisk Assessment in Bop ProjectsHarishNo ratings yet

- Kisala - The Effect of Credit Risk Management Practices On Loan Performance in Microfinance InstitutionsDocument69 pagesKisala - The Effect of Credit Risk Management Practices On Loan Performance in Microfinance Institutionsjhomar jadulan100% (3)

- RCBC V Arro To PBTC v. TambutingDocument5 pagesRCBC V Arro To PBTC v. TambutingPeng ManiegoNo ratings yet

- Funds Flow AnalysisDocument38 pagesFunds Flow AnalysisAditya KiranNo ratings yet

- BillDocument10 pagesBillAlok TiwariNo ratings yet

- Loan Amortization Schedule1Document9 pagesLoan Amortization Schedule1api-354658624No ratings yet

- Law Act 4 Employees Social Security Act 1969Document140 pagesLaw Act 4 Employees Social Security Act 1969epeguamNo ratings yet

- TR 256 - Top Income Shares in GreeceDocument28 pagesTR 256 - Top Income Shares in GreeceKOSTAS CHRISSISNo ratings yet

- Banco Filipino Savings and Mortgage Bank Vs The Monetary BoardDocument3 pagesBanco Filipino Savings and Mortgage Bank Vs The Monetary BoardRonald LasinNo ratings yet

- Subiect: of WithDocument3 pagesSubiect: of WithCarlos JesenaNo ratings yet

- Venture CapitalDocument84 pagesVenture CapitalAshar RazaNo ratings yet

- Sap Down Payment ProcessingDocument4 pagesSap Down Payment Processinglukesh_sap100% (1)