Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reading Dystopian Fiction After 9:11

Uploaded by

mickeymetalOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Reading Dystopian Fiction After 9:11

Uploaded by

mickeymetalCopyright:

Available Formats

A World Neither Brave Nor New: Reading Dystopian Fiction after

9/11

Efraim Sicher

Natalia Skradol

Partial Answers: Journal of Literature and the History of Ideas,

Volume 4, Number 1, January 2006, pp. 151-179 (Article)

Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press

For additional information about this article

Access Provided by Curtin University of Technology at 10/07/10 8:17AM GMT

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/pan/summary/v004/4.1.sicher.html

A World Neither Brave Nor New:

Reading Dystopian Fiction aIter 9/11

EIraim Sicher

Ben Gurion University oI the Negev

Natalia Skradol

Tel Aviv

Under the general demand Ior slackening and

Ior appeasement, we can hear the muttering oI

the desire Ior a return oI terror, Ior the realization

oI the Iantasy to seize reality.

Lyotard 1984: 82

On ne peut pas crire sur ce sujet mais on ne

peut pas crire sur autre chose non plus. Plus

rien ne nous atteint.

Beigbeder2003:18

The End without Ending: The Intrusion oI the Real

9/11 has been imagined beIore in countless hijack or terminal disaster

Iilms such as Blade Runner, Apocalypse Now, and Independence Day.

Slavoj Zizek presents the TV coverage oI 9/11 as the Hitchcock moment

oI horror that is actually happening; it is the intrusion oI the real into

Iiction. This is what made similar scenes in horror movies unscreenable

in the immediate weeks aIter 9/11 and sent the CIA scurrying aIter

Hollywood scriptwriters in order to try to understand the terrorists. It is

an intrusion, Zizek argues, that is the ultimate marker oI the "passion

Ior the Real" (2002: 16-20). One instance oI this intrusion occurs in the

Iilm The Matrix (1999) when the hero awakens Irom what he thought

* This essay is dedicated to the memory oI Philippa Tiger, who Iirst suggested the

rereading oI Auden. The authors are grateIul to Dr Yael Ben-Zvi, who Iirst pointed out to

us the reversal oI reality and Iiction in Matrix. Special thanks go to Peter Hutton and Joel

Meyerowitz Ior kind permission to use their work.

Partial Answers 4/1 (2006)

152 EIraim Sicher and Natalia Skradol

was "real" into the "real reality" and sees a desolate landscape littered

with the burned ruins oI Chicago aIter a global war. The hero then

encounters resistance leader Morpheus, who utters the ironic greeting:

"Welcome to the desert oI the real."1

This essay explores how our imagining oI Iuture disaster in dystopian

literature is re-visioned and revised by the aIter-image oI the disaster

that has actually happened. II there has been a change in our reading

oI literature and Iilm since 9/11, this change may not be quantiIiable

(a measurement beyond the scope oI this essay and possibly beyond

Ieasibility), but it may teach us something about the way in which the

aIterimage oI the disaster that has actually occurred aIIects our reading

in the would-be anterior Iuture oI imagined terminal catastrophe, the

imagined end oI society, oI time, oI the story. A similar process oI

reinterpretation happened aIter the 2004 tsunami disaster in Asia,

which seemed to outdo the scenes in the Iilm The Day AIter Tomorrow

(2004) oI a submerged New York. Each oI these events challenged the

human ability to control history and the environment.

Both natural and man-made disasters leave deep impressions on

the imagination and on philosophy. For example, the 1755 Lisbon

earthquake destroyed an imperial capital equivalent to the size oI

prewar London and made a laughing-stock oI Leibnizian optimism in

Voltaire's Candide. Yet natural disasters do not usually have political,

military, and historical signiIicance and, unlike 9/11, are rarely thought

oI as marking the end oI an era. 9/11 was an intrusion oI the real that

made it impossible to un-imagine dystopia as nightmare or Iantasy. It

is not a matter oI whether or not Utopian thought is still sustainable or

practical, but oI what has happened in postmodern Iiction under the

impact oI a real collision oI reality and imagination. This destruction

was not just another demonstration oI a culture oI aIter-images but a

singular event, perhaps an ur-event, which showed that the world was

in a permanent state oI unending disasters.

What could looking backward Irom aIter 9/11 mean Ior our reading

oI dystopian texts? We do not have in mind mere "Ioreshadowing" (cI.

Bernstein 1994), or Jacques Derrida's delineation oI nuclear-holocaust

' See Zizek 15. Art Spiegelman's In the Shadow oI No Towers makes a similar point

when he has a billboard Ior Arnold Schwarzenegger's Collateral Damage displayed

against the background oI the real terrorist scenario oI the burning Towers (2004: 2). On

the delayed release oI Collateral Damage and the post-9/11 reception oI war Iilms see

Lowenstein 2003.

A World Neither Brave Nor New: Reading Dystopian Fiction aIter 9/11 153

discourse as an entirely Iictional genre (since it had not happened and

could not happen without erasing all record, all archive, oI its having

happened).2 Rather, the eIIect oI reading any dystopian text post

Iactum, when history has given chilling new meaning to the original

context in which the disaster was imagined, reverses the relationship

between Iiction and reality and raises unsettling postmodern suspicions

oI the "real" as something that can be known otherwise than as an

aesthetic arteIact. We are always, when reading narratives, looking

Iorward, in all senses, to the end, but in this case the "end" precedes

our reading oI past narratives that imagine the Iuture. Superimposed

on our interpretation is the disaster having already happened (quite

apart Irom any meaning the disaster's may have in itselI as a discrete

historical, political, or physical event).

We shall see that a Iurther stage has been reached when dystopian

Iiction has become a Iact, no longer a cautionary tale oI the imagination.

But then destruction is embedded in Western culture. Satirized by Don

DeLiIIo, postwar America had become a site oI catastrophe beIore

disaster struck; the destruction oI New York must also be seen in terms

oI postmodern aesthetic theory expounded by Jean Baudrillard and

Paul Virilio. Finally, Frdric Beigbeder, Ian McEwan, and Jonathan

SaIran Foer respond to 9/11 in novels that grapple with what 9/11 and

its aItermath imply Ior representation and Ior the novel Iorm.

What 9/11 has shown is that the relationship oI the real and the

imagined in dystopian Iiction has been reversed, since hypermediated

image has eclipsed the event and Iiction has become lived experience.

There is an uncanny sense oI an end that has been almost predestined,

like Winston's Ieeling oI dj vu in Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four

when he enters the Golden Country and makes love with Julia in a

Miltonian Paradise, a scene he has dreamed. Indeed, the topos has been

reworked enough times in literature to be uncannily Iamiliar. Read

in this context, T. S. Eliot's remark in "Tradition and the Individual

Talent" about the duty oI any true artist to "live ... in what is not

merely the present, but the present moment oI the past" (1976: 22)

acquires a new and sinister meaning.

II the Christian promise oI an apocalyptic end was repeatedly

disappointed, it could be argued that "the typological repetitions that

punctuate the more linear apocalyptic mythos entail a diIIerent sort oI

2 See Derrida 1984, as well as Saint-Amour 2000.

154 EIraim Sicher and Natalia Skradol

negotiation oI identity and diIIerence, one... whose disconIirmation (or

the Iailure oI the attainment oI apocalyptic closure), Iar Irom discrediting

or invalidating the deIining mythos or promise, serves to propel the

mythos Iorward, oIten in a redeIined and expanded Iorm" (Robson

1995: 62). In narrative terms, such repetition is built into an American

cultural discourse that can be traced back to the Pilgrim Fathers, who

believed they had arrived in the postapocalyptic promised land. In a

sense, the end was always there, since utopia presumes that something

(the rotten state oI society, human corruption, gender diIIerence, or liIe

on earth) must Iirst come to an end. Seen this way, apocalyptic visions,

in the Christian scriptures or in revolutionary socialism, build terminal

disaster into eschatology, so that the repeated non-IulIillment oI the

promised salvation implies a constant repetition oI catastrophe. Worse,

when disaster is not Iollowed by a brave new world, all that remains

is a permanent state oI disaster. Dystopian Iiction is thus implicitly

postapocalyptic.

At the same time, spatio-temporal repetition may be built into

cultural texts, such as music (see Lyotard 1988: 165), and Paul Ricoeur

reminds us that literary plot is in essence repetitive (1980: 178). It is a

Iamiliar paradox, moreover, that when we begin to read a novel, the end

oI the story has already been written, so that the Iuture has already been

imagined as the past in narrative time; in history the story is always

retold when we know the ending, even iI we cannot know its meaning.

ThereIore the dystopian Iuture is always past tense, retold and revised.

But iI dystopia can no longer be imagined except in the already past

Iuture, the story can only be repeated as a continual end, a disastrous

writing in Maurice Blanchot's terms. Speaking oI Auschwitz (a disaster

incomparable, least oI all to 9/11 ) in The Writing oI the Disaster, Blanchot

remarks that we live aIter the unthinkable has been thought. Although

it does not actually touch us physically, we live everywhere under its

threat: "The disaster ruins everything, all the while leaving everything

intact" (1986: 1). In any case, we can barely express the Ieeling oI being

unable to write aIter the disaster. II all representation is inadequate, then

reading aIter disaster substitutes Ior an act oI representation.

Some oI the implications oI reading literary dystopias aIter 9/11

may lie in the deIinition oI dystopia and conIirm what we have long

known, namely that there is no return to innocence because there was

none. Utopia and anti-utopia have always been two sides oI the same

coin: "As nightmare is to dream . . . anti-utopia has stalked utopia

A World Neither Brave Nor New: Reading Dystopian Fiction aIter 9/11 155

Irom the very beginning. ... As in Freud's theory oI the unconscious,

the very announcement oI utopia has almost immediately provoked

the mocking, contrary, echo oI anti-utopia" (Kumar 99-100). Dystopia

(which should be distinguished Irom anti-utopia) is not so much an

argument against utopia, as its obverse, a utopia that will inevitably go

wrong; it is utopia discovered to be the "bad place" (see Booker 1994;

Moylan 2000:111-99). John Stuart Mill mocked his opponents as "dys-

topians" or "caco-topians" because, he declared, "What is commonly

called Utopian is something too good to be practicable; but what they

appear to Iavour is too bad to be practicable."3 Surely there has always

been a dystopian streak in Utopian writing, especially iI More's Utopia

is read ironically, as both u-topia and eu-topia, as a critique oI what is

wrong with England's social and economic situation that is Iollowed,

in the second book, by a demonstration, through the unreliable

narrator (a veritable "speaker oI nonsense"), oI a perIect society that

is impossibly "No-Where." Nevertheless, the satires directed at ideal

societies by SwiIt, Johnson, or Voltaire did not deter Utopian thinkers

in America or Europe Irom planning and occasionally building utopias

based on ideals oI universal reason and happiness. Typically, these

Utopian projects can be brought about only by transIorming human

nature, whether by social and genetic engineering (Brave New World),

eugenics (The Coming Race), genocide (Mein KampI), behavioral

conditioning (Waiden 2), mind control (Nineteen Eighty-Four), or the

banning oI literature (Fahrenheit 451). There is something inhuman

(and thus potentially dysIunctional or dystopian) in the idea oI a utopia

which requires that human society as currently constituted be replaced

(whether through natural selection or coercion) by a social order based on

diIIerent (implicitly non-human) characteristics. These characteristics

are usually based on uniIormity, conIormity, and unanimity - the very

values that brought the downIall oI the biblical Tower oI Babel.

In his critique oI the inhuman absolutism oI Utopian projects which

allowed only one possible solution to social ills, Iorced on people

dogmatically, Isaiah Berlin quoted Immanuel Kant's dictum that

"out oI the crooked timber oI humanity no straight thing was ever made. "4

Berlin detected the seeds oI revolt against the Utopian construction

3 Speech to the House oI Commons, 12 March 1857; quoted in Kumar 447, note 2.

4 "|A|us so krummen Holze, als woraus der Mensch gemacht ist, kann nichts ganz

Gerades gezimmert werden" ("Idee zu einer allgemeinen Geschichte weltb/rgischer

Absicht" |1784|, quoted in Berlin 19).

156 EIraim Sicher and Natalia Skradol

oI universal harmony in German romanticism and in Promethean

Byronic heroes (Berlin 44-45). Lewis MumIord, too, in his salutary

preIace to the 1962 edition oI The Story oI Utopias, declares that the

eighteenth-century Utopians were mistaken in thinking that human

nature was malleable and society perIectible (3). Like Berlin, MumIord

maintained his Iaith in the latent possibilities that could lead to a better

world iI the warnings oI Utopian projects were heeded, despite the

dent that World War I made in those hopes when it "suddenly

reversed the currents oI our liIe" (2). In a passage that reads quite

ironically now, MumIord dreamily looked out oI his tenement window

over the rooItops oI Manhattan, seeking inspiration Ior the Utopian

potential oI the present and relieI Irom its ugliness in the "pale tower

with its golden pinnacle gleaming through the soIt morning haze" (25).

Literary dystopia gives a negative appraisal oI the here-and-now,

a satire oI what is already possible but not desirable, as distinct Irom

Iantastic science Iiction set elsewhere, which may be desirable but not

realizable. In the century oI communism and Iascism, the revolutionary

Utopian movements oIIered the implementation oI ideals, while

dystopia mocked the tyranny oI idea (see Kumar 125). The Russian

philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev predicted that utopia was only too

possible and intellectuals would have to Iight to prevent it, a prophecy

Aldous Huxley used as the epigraph to his dystopian novel, Brave New

World (1932). Berdyaev, writing at the beginning oI Soviet rule beIore

he was expelled by the Bolsheviks, saw that the border oI reality had

been crossed when Utopian theory had become totalitarian practice and

dystopians would have to imagine a resistance to this scourge out oI

Dostoevsky's The Possessed beIore the West became inIected too (see

BerdiaeII 262-66).5

The End in the Beginning: Disaster as a Cultural Norm

Cet vnement a exist, et on ne peut pas le raconter.

Beigbeder 19

The reasons why 9/11 seemed to repeat a dystopian scenario have

to do with a paradigm in Western culture. Despite the conclusion oI

the commission investigating 9/11 that there had been a Iailure oI

5 See also Hoyles 120-21.

A World Neither Brave Nor New: Reading Dystopian Fiction aIter 9/11 157

imagination in the intelligence community,6 in popular culture the all too

Iamiliar scene oI destruction seemed incredible because it was, indeed,

all too Iamiliar. The common comparison with other disasters that

delivered a Iundamental psychological shock and served as historical

or epistemological turning-points, such as the sinking oI the Titanic or

the attack on Pearl Harbor, underscores the paradoxical unexpectedness

and predictability oI the event. The more the catastrophic end becomes

mythologized in collective memory and popular culture, the less we

expect it to happen as a "real" event and the more predictable it seems

to be when it has happened. Susan Sontag once commented (1966:

209-25) that science Iiction Iilms and novels are invariably more about

disaster than science since they go back to the oldest plots oI heroes

battling evil against all odds and reenact the destruction oI great cities

(such as Babylon in D.W. GriIIith's 1916 Iilm Intolerance).

The "ruins oI time" motiI (a poetic tradition Irom Edmund Spenser

to Robert Lowell) helps keep in mind the seeds oI destruction on which

Britain built its imperial project, as Rome had done beIore. Social critics

Irom Carlyle to Ruskin envisioned the Iuture ruins oI the capitalist

empire, the new Tower oI Babel/Babylon. Gustave Dor's vivid 1872

etching oI "The New Zealander" presents a vision oI the ruins oI London

150 years later, visited by an aborigine tourist. The collapse oI temples

and towers is at the core oI our cultural sensibilities - whether they

represent belieI systems, military power, or global commerce - and it

was science, identiIied with progress and rationality, that has perIected

the means oI eIIicient lethal destruction. Beginning with the American

Civil War7 and the Franco-German War, writers imagined the war to

end all wars. A memorable example is H. G. Wells's War oI the Worlds

(1897),8 which, in Orson Welles's radio rendition on October 30, 1938,

caused panic in America. Toppling towers and alien invasions have long

6 National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, August 21, 2004,

www.9-1 lcommission.gov: 339`-7.

7 In his 2004 discussion oI the poverty oI literary responses aIter 9/11, Christopher

Merrill notes that the American Civil War marked a loss oI innocence which inspired

Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman to create a new poetics oI grieI (70-77). His point is

that Whitman and, in his Gettysburg Address, Abraham Lincoln were able to articulate a

Iuture Ior the American nation in a way not matched by President George W. Bush aIter

9/11.

8 See Kumar 65. Kumar names Sir George Chesney's The Battle oI Dorking (1871)

as the Iirst work oI this kind.

158 EIraim Sicher and Natalia Skradol

been the staple oI science Iiction plots, though since World War II no

hero trying to save the world could be innocent about the global threat

under which we all live, a collective trauma oI a global destruction which

has already happened (see Sontag 215, 225). So, to a Western public,

the targeting oI the Twin Towers and the Pentagon might have seemed

(however Ialsely) a scenario already previewed, prescribed, pretexted...

We live in a continual disaster zone and thereIore, in rereading the

modernists, we recognize that Ior them the apocalypse was present

tense, not an eschatological Iuture. Sitting in "one oI the dives / On

FiIty-second Street / Uncertain and aIraid," W. H. Auden smelt the

"unmentionable odor oI death" that "OIIends the September night."9

On that other September night, under the collective strength oI the

skyscrapers oI Manhattan, Auden despaired oI the Ialse hopes oI a

"low dishonest decade," yet put his Iaith in the individual aIIirmation oI

Iidelity. Auden could not see the coming end that T. S. Eliot described

in "Little Gidding." He could not see what that poetic Iire-watcher saw

in the Dantean inIerno oI the Blitz. However, Yeats, the ghost who

walks the dead patrol with T. S. Eliot, knew that aIter the war to end all

wars, the Great War oI 1914-1918, the next war was coming, and that

iI nothing "drastic" was done, airplanes and Zeppelins would Ilatten

the city.10 Written in July 1936, during the Spanish Civil War, a year

beIore Guernica provided Picasso with an image oI modern war, "Lapis

Lazuli" is not so much a prediction oI the coming global conIlagration

amid hysterics and playacting, as an acknowledgment oI the ancient

wisdom oI the Chinese and the gaiety in their wrinkled eyes which

have seen and outlasted the Iall oI many empires.

Countless novels and Iilms have assumed that disaster would lead

to the end oI America's liberal democracy. In Margaret Atwood's The

Handmaid's Tale (1989), Ior example, an ecological catastrophe has

taken place, the President and Congress have been gunned down (Ior

which "Islamic Ianatics" are blamed), and the United States has been

transIormed into a dystopian patriarchy based on a Iundamentalist

Christian right-wing hierarchy that enslaves women. British dystopias

are no saIer. In A Clockwork Orange (1962) Anthony Burgess imagines

the introduction oI sadistic mind control based on Soviet techniques.

9 "1st September 1939" (Auden 1945: 57). These lines were oIten quoted aIter 9/11

(see Merrill 69-70).

10 "Lapis Lazuli" (Yeats 1958: 292).

A World Neither Brave Nor New: Reading Dystopian Fiction aIter 9/11 159

In another novel, 1985 (1978), he imagines that an Islamic republic has

been proclaimed in the United Kingdom.

When the planes hit the Towers on September 11, 2001, despite

some tottering oI stock markets, the global superpower, the United

States oI America, did not collapse as was Ieared. Nevertheless, the

vision oI the monuments oI empire crumbling in a Iew moments

exceeds our capacity to imagine worst-case scenarios. At the same

time, the Iailure to conIront the preexisting possibility oI the disaster

and to Iind adequate cultural responses to 9/11 seems to say something

about a postapocalyptic culture which has already imagined the Iinal

disaster. James Berger wrote his 1999 book AIter the End during the

millennial high alert beIore that moment when New York moved Irom

the list oI cities oI culture (Paris, Vienna, Prague) to cities oI destruction

(Jerusalem, Nineveh, Babylon). Perhaps Ior this very reason, Berger's

observation remains true: we are always writing aIter the end that

has been written into Western culture - Irom the Book oI Revelation

through Vonnegut, Pynchon, and DeLiIIo.

AIter the worst has already happened (the Bhophal disaster in India,

Chernobyl, 9/11, or the SARS epidemic), the Iuture can be imagined

as a replay oI disaster scenarios, in which we compulsively repeat

past imagining oI the Iuture. This is a distinctly postmodernist marker

oI an end to the Western tradition oI looking Iorward to the terminal

transIormation oI the world either into a prelapsarian edenic state (a

regression to a primeval paradise) or into a radically new political

reality (a revision oI history or rewriting the Iuture). The occurrence oI

the Ioreseen catastrophe lends an uncanny inevitability to history. Kurt

Vonnegut parodies this backward reading oI history in Timequake ( 1997)

when he describes the "clambake" in February 2001 which reverses

time and returns the Iree will that has been lost to the inevitability oI

history's rerun. Airplanes on autopilot are crashing and the Iact that

this unending disaster is dreamed up by a science Iiction writer called

Kilgore Trout does not prevent us Irom realizating that this Iantasy

oI the Iuture has happened beIore. In Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse Five

(1969), Billy Pilgrim, who is living a Kilgore Trout Iantasy oI visitors

Irom outer space, complains that he cannot change the past, present, or

Iuture. There is no human Ireedom except to press the destroy button.

History is a series oI destructions. The replay backwards oI a movie oI

the Allied Iirebombing oI Dresden is a reprise oI the point that there is

no why in history. Moreover, in the novel, the historian David Irving's

160 EIraim Sicher and Natalia Skradol

revisionist account oI this incident is taken more seriously than Bill's

own personal memory oI being there as a witness.

In Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow (1973), the screaming

oI the V-rockets repeats previous disasters and promises a spectacle

as great as the destruction oI the Crystal Palace, the glass monument

to the triumph oI the capitalist utopia at the center oI the 1851 Great

Exhibition (it burnt down in 1936):

A screaming comes across the sky. It has happened beIore, but

there is nothing to compare it with now.

It is too late. The Evacuation still proceeds, but it's all theatre.

. . . He's aIraid oI the way the glass will Iall - soon - it will be

a spectacle: the Iall oI a crystal palace. But coming down in

total blackout, without one glint oI light, only great invisible

crashing.11

We start at Absolute Zero, where Wernher von Braun 's rocketry links

Nazi total war with the NASA space program in an apocalyptic vision

oI erotic Iantasies oI sadomasochistic ecstasy. This reminds us that

"ground zero" derives Irom the atomic testing grounds in Alamogordo

(see Davis 2003); the Manhattan Project is a code name Ior destruction

that, in a macabre twist, has, as it were, struck home. The endgame

dates Irom World War II, Vonnegut avers in Timequake, when the Iirst

atom bomb was dropped on Japan.

Other literary dystopias show how much the imagined end in

American Iiction has become an essential element oI postmodernist

poetics. Don DeLillo's White Noise (1984) is about the imperceptible

presence oI death which has been invisibly introduced into the lives

oI ordinary Americans (as the Chernobyl Iall-out would do a year or

two later, an unseen disaster whose damage could not be contained

by the habitual lies oI the regime). The Airborne Toxic Event slides

imperceptibly, namelessly, into the daily emergency routine oI the

crowd waiting anxiously to be told that the authorities know what is

happening - waiting to be transported, processed, evacuated. But the

diIIerence between simulation and a real emergency has been eroded

" Pynchon 1975: 3. Quoting this passage, Anustup Basu notes the proximity oI event

and phenomenon; Iailure to distinguish between these two categories oI thought has made

it possible to present 9/11 as a crisis situation without understanding "that which allows

the screaming to both recur in a calendar oI disasters, and at the same time, have an

untimely and incomparable aspect to it" (2003: 11).

A World Neither Brave Nor New: Reading Dystopian Fiction aIter 9/11 161

(a SIMUVAC oIIicial explains that they are using the real thing as an

exercise!) In White Noise, moreover, the aIterimage makes us think

that we are seeing the real thing. This is as close as you can get, only

we need to get closer:

"Come on hurry up, plane crash Iootage." Then he was out the

door, the girls were oII the bed, all three oI them running along

the hall to the TV set.

I sat in bed a little stunned. The swiItness and noise oI their

leaving had put the room in a state oI molecular agitation. In

the debris oI invisible matter, the question seemed to be, What

is happening here? By the time I got to the room at the end oI

the hall, there was only a puII oI black smoke at the edge oI the

screen. But the crash was shown two more times, once in stop-

action replay, as an analyst attempted to explain the reason Ior

the plunge. (DeLiHo 1986: 64)

The event is no longer an event but its aIterimage, like the clip, endlessly

replayed, oI the second plane penetrating the World Trade Center. Zizek

sees the repeated shots oI the second plane crashing into the WTC as

approximating the appeal oI a snuII movie, the ultimate sadistic act

endlessly repeated and prolonged in virtual reality (5-6,11). Every image

oI disaster, even iI broadcast live by satellite, becomes an aIterimage

once it has happened. The aIterimage oI the disaster, Baudrillard

tells us, Ieeds an insatiable hunger Ior worse, Ior a Bataillean excess:

"Every disaster made us wish Ior more, Ior something bigger, grander,

more sweeping" (Baudrillard 2002: 11). In much the same way, the

protagonist oI Crash (1973) by J. G. Ballard, the science Iiction author

oI a number oI terminal apocalypses, is constantly on the lookout Ior

victims oI more and more atrocious car crashes.

That America and especially New York can be understood only as

images is the sustaining device oI DeLillo's Mao II ( 1991 ), a work that

links international terrorism with the art oI the novel in a metaIictional

dystopian here and now. Even beIore the aIterimage oI their downIall

in real liIe, the Twin Towers exist only as an image, seen Irom the

studio oI Brita, a proIessional photographer who is turning her mental

image oI the writer Scott into publicity images:

Out the south windows the Trade towers stood cut against the

night intensely massed and near. This is the word "loomed" in

all its prolonged and impending Iorce. (DeLiIIo 1991: 87)

162 EIraim Sicher and Natalia Skradol

As in White Noise, the crowds are Iixated by mass death. The mass

weddings oI the Moon cult, Islamic Iundamentalists greeting Khomeini,

and the Iuneral oI Chairman Mao are televised images that reIlect the

complete loss oI individual human identity, as well as oI community,

oI emotional connection. Everything is done by remote access and

routine. A bomb explosion is something that really happens, but it can

only be perceived in a Iragmented image oI a shard oI glass, or as

a press event. Freedom is a concept tied to the media announcement

oI a hostage's release. So powerIul is an image that the photo oI a

corpse may be more important to the terrorists than any exchange or

deal. The Russian revolutionary slogan adopted by a German neo-Nazi

group, "the worse the better," sums up the cynical state oI aIIairs in

which only when you are killed are you noticed; prime-time ratings go

to mass killers and suicide bombers. While his hooded captors leave

the kidnapped poet only images to grasp, another protagonist, Karen,

discovers New York's own Beirut, a tent city oI disaIIected homeless

drug addicts and illegals. DeLiIIo warned that hostage-taking was a

rehearsal Ior mass terror, but his scenario oI midair explosions and

crumbling buildings, "the new tragic narrative" aIter Beckett (1991:

157), is, since 9/11, no longer a dystopia oI the Iuture.

In a 1986 essay on New York (1989a: 13-24), Baudrillard likewise

noticed the total isolation oI the individual that makes relationships

outside gangs unthinkable. The world's capital has reached a degree oI

atomization and crowdedness that has outstripped the agglomeration

that baIIled Friedrich Engels in the streets oI London. The New York

Marathon, that "end oI the world show," brings a message not oI

victory but oI catastrophe because each oI the 17,000 runners suIIers

alone Ior the sake oI the achievement oI saying "I did it" (19-20).

"I did it" sums up the mystical decadence oI a vibrant and totalized

city, its cold architecture, the animal attraction oI skin color, and above

all the exhaustion oI its Utopian projects, such as the space program,

once they, too, have been implemented. Further, "America is neither

dream nor reality. It is a hyperreality. It is a hyperreality because it

is a utopia which has behaved Irom the very beginning as though it

were already achieved." America has, indeed, become the "perIect

simulacrum" (28).

A World Neither Brave Nor New: Reading Dystopian Fiction aIter 9/11 163

The End beIore the End: Imagining the End oI the World

Tout gratte-ciel est une utopie.

Beigbeder 26

Another way oI looking Iorward to the Iuture end was to wait Ior the

barbarians. The Greek poet Irom Alexandria, Constantine CavaIy

(1863-1933), mused on what would happen iI the long expected

barbarians did not arrive: "So now what will become oI us, without

barbarians./ Those men were one sort oI resolution."12 But these

necessary barbarian Others are no good iI they are already here. As

Morris Berman, author oI The Twilight oI American Culture, writes

in "Waiting Ior the Barbarians" (2001), the parallel between the Iall

oI Rome and America aIter 9/11 is impressive because the decay

caused by inner barbarism does not take account oI the destruction

Irom without.13 The chronically bored hospital guard on duty in the

movie The Barbarian Invasions I Les Invasions Barbares (dir. Denys

Arcand, Rmy Girard, and Stphane Rousseau, Canada, 2003) is not

particularly impressed by the repeated Iootage oI the 9/11 catastrophe;

like T. S. Eliot's Tiresias, he probably Ieels he "has seen it all beIore,"

in the invasion oI the civilized barbarians within his own society, in his

own hospital, right by his desk.

What in the title oI his essay on 9/11 Don DeLiIIo calls the "Ruins

oI the Future" is a continuing disaster, precisely in the Utopian mass

circulation oI virtual goods and inIormation:

In the past decade the surge oI capital markets has dominated

discourse and shaped global consciousness. Multinational

corporations have come to seem more vital and inIluential than

governments. The dramatic climb oI the Dow and the speed oI

the internet summoned us all to live permanently in the Iuture,

in the Utopian glow oI cyber-capital, because there is no memory

there, and this is where markets are uncontrolled and investment

potential has no limit.

According to DeLiIIo, this is a disaster that literally ruins the Utopian

Iuture and demolishes social constructions oI technological progress

12 "Waiting Ior the Barbarians" (CavaIy 2001: 93).

13 Merrill cites CavaIy's poem to make an argument Ior the power oI literature to bring

empathy (2004: 74-79).

164 EIraim Sicher and Natalia Skradol

and endless happiness, leaving us with nothing to look Iorward to, only

the memory oI an end. The destruction Irom without is not the revolt

oI the repressed and the needy against globalization but a Iorce totally

Other and incomprehensible to the mind oI the empire, untouched, as

DeLiIIo tells us in his essay, by the woman in the supermarket, yet

touching every aspect oI the capitalist utopia, Irom its skyscrapers to

Palm Pilots.

It has been suggested (Abel 2003) that DeLillo's "The Ruins oI the

Future" may question our capability to respond because its rhetoricity

determines the understanding oI what 9/11 means. In other words,

the imaging oI the event may deIer, though not totally suspend, any

judgmental position, and the aesthetic statement oI this dilemma

impedes getting at the essence oI what happened. A good illustration

is the manipulation oI the viewers' political stance through visual

interpretation in Michael Moore's movie Fahrenheit 9/11 (2003).

Cinematic imaging prevents us Irom seeing the event itselI, while

hypermediation shapes public belieI.

DeLillo's real-time scenario oI a Third-World country in which people

wander helplessly in dust masks, clutching photos and descriptions oI

the disappeared, concludes with a surprising aIIirmation oI a counter-

narrative to the Cold-War arms race or the Bush administration's

declaration oI a (Iourth) world war on "the evil ones." DeLiIIo speaks oI

the power oI American technology, its own "astonishments," combined

with the multiethnicism oI New York, to survive mindless attacks. Jean

Baudrillard sees it diIIerently, as a millennial burst oI terminal events

that began with the death oI Princess Diana and culminated with the

mother oI all events, 9/11.u

The Iascination with images oI destruction imparts a desire Ior

destruction embedded in the power structure itselI, which enacts

our dreams oI its happening (see Baudrillard 2002: 5-6). The twin

destruction rules out accident and goes beyond any ideology,

energizing the absolute and irrevocable event: a zero-death game that

14In his 1989 essay "The Anorexic Ruins," Baudrillard announced that in a sense

the year 2000 would not take place because there were no more events; the end had been

played out so many times that the postapocalyptic world was a rerun oI a spectacle, while

history, culture, and truth were absorbed by the simulated image. In Baudrillard's America

this end oI ends was located in the trajectory Irom the old culture oI Europe to the utopia

oI America, where everything speeded to a terminal end. This postapocalyptic topos itselI

partakes oI the apocalyptic myth oI the Pilgrim Fathers (see HeIIerman 171-72).

A World Neither Brave Nor New: Reading Dystopian Fiction aIter 9/11 165

deIies interpretation. The terrorists hijacked the media, in Baudrillard's

analysis, because the "image consumes the event, in the sense that it

absorbs it and oIIers it Ior consumption" as an "image event" (27). The

Iixation on aIterimages oI the event blocks out interpretive strategies

that would "Iit" this event into some historicizing, ideological, or ethical

pattern, perhaps even into Baudrillard's own postmodernist anti-

allegories oI counter-meaning. The striving Ior rational progress, Ior

Utopian happiness, would then have to be reread as a premonition oI

an end that has already "happened" and is now being experienced in

what Baudrillard sees as a radical and violent reintroduction oI a real

event into the proliIeration oI simulacra and banal images oI pseudo-

events. It is in this sense that "|t|he structure oI the spectacle . . .

'revokes' the very Utopian desires . . . that its images 'provoke.'... It

is this contradiction that is expressed by postmodern myth's perpetual

oscillation between utopia and dystopia" (Durham 5).

The End oI the End: The Postmodern Dystopia

En anglais, "end" ne signiIie pas seulement la

Iin mais aussi l'extrmit.

Beigbeder 20

Rereading dystopian Iiction must contend with the loss oI Iavor

oI utopianism in a consumerist mass-culture which values instant

gratiIication and Ietishizes material objects oI desire. The egocentric

meanness oI "me-ness" stresses the individual at the expense oI shared

ideological goals. Family ties, group identity, or the collective tend not

to be Ieelgood experiences in the global IastIood McDonald's empire.

When power is in the hands oI multinational corporations, Lyotard tells

us, an anything-goes eclecticism characterizes a zero degree oI culture,

and "knowledge" is relegated to TV trivia games (1984: 76). Party or

organized socialism has been widely discredited, and with the Iall oI

the Berlin Wall many "isms" oI all kinds have lost their hold, resulting

in the collapse oI the myth oI progress (see Jacoby 1999: 1-27).

In Dreamworld and Catastrophe: The Passing oI Mass Utopia

in East and West (2000), Susan Buck-Morss comments that Walter

Benjamin's Traumwelt (dreamworld) oI early commodity capitalism

has been replaced by Adorno's diagnosis oI "absolute reiIication oI the

166 EIraim Sicher and Natalia Skradol

world" (see Adorno 1991,1: 40). Buck-Morss's reading oI Benjamin's

dreamworld and catastrophe as two "extremes oI mass utopia" (2000:

xi) disregards an essential aspect oI Benjamin's concept oI historical

dynamics. For Benjamin, catastrophe is not opposed to dreamworld

but is present already at the moment oI the appearance oI dreamworld

images, since "every epoch, in Iact, not only dreams the one to Iollow

but, in dreaming, precipitates its awakening. It bears its end within itselI.

... we begin to recognize the monuments ... as ruins even beIore they

have crumbled" (Benjamin 1999:13). What Benjamin said oI bourgeois

collective Iantasies can be extended to the modern Western culture oI

consumerism. Dreamworld carries the catastrophe within itselI. But

the Iormula can also be reversed: the catastrophe is an announcement

oI a dreamworld oI the Iuture, iI dreamworld is to be understood as

an assemblage oI collective Iantasies. Buck-Morss considers there to

be little diIIerence between Soviet Russia and America in this respect

and points to a parallel vision and disillusionment in Russia and

America in the twentieth century: King Kong straddling the Empire

State building is contemporary with Stalinist monumental architecture

(Buck-Morss 17488). Tatlin's vision oI mechanization oI the body,

as in his Letatlin Ilying machine (1929-1932) or his constructivist

design Ior the never built Monument to the Third International (1920),

conveyed the Iuturistic dimension oI technological utopianism that

remained, however, no more than a dream Ior the masses (see Stites

1989). But Stalinist towers and palaces, symbols oI totalitarian power,

cannot be compared with the prominence skyscrapers in the American

dream, which consigned those excluded Irom them to the poverty oI

the ghetto: no expression oI opposition to Stalinism in any Iorm was

tolerated - and the day oI avant-garde Iuturism in the Soviet Union was

all too short.

Seen Irom aIter 9/11, the twentieth century marks the twilight

oI utopia. Dystopia has Iinally arrived because, on the one hand,

the reconstitution oI society seems impossible while, on the other,

technology threatens basic concepts oI individual Ireedom and oI

human liIe. It may be that modernity is simply a state oI Iatigue, as

it was Ior Nietzsche, and that the world is slipping into idleness - the

perpetual leisure that makes any other Iorm oI utopia unthinkable.

Writing in 1888, Nietzsche asked: "Where does our modern world

belong - to exhaustion or ascent?" His characterization oI the epoch by

the metaphor oI Iatigue was symptomatic oI a general Iear shared by the

A World Neither Brave Nor New: Reading Dystopian Fiction aIter 9/11 167

European middle classes that humanity was depleting its "accumulated

energy" and Ialling into that sleep, which was "only a symbol oI a

much deeper and longer compulsion to rest."15 Against the background

oI the pessimism that grew out oI the wholesale slaughter oI World War

I, Oscar Spengler 's Decline oI the West (1918) and Freud's Civilization

and its Discontents (1930) can be seen as strong anti-utopian key texts.

As Ior the more Iuturistic projects oI modernism, their inebriating

Utopian spirit generated an expectancy curtailed by the trench warIare

oI World War I and paradoxically suggested a Iuture that would cancel

both the present and modernism itselI.16 It is hardly surprising that,

Iollowing the liberation oI Europe in 1945, which revealed the Nazi

concentration camps, and under the perceived threat oI communist

invasion, there was a marked increase in new horror tales that depicted

impending, terminal disaster overtaking the mightiest nation in the

world (see Kumar 380-88).

Utopia was, oI course, Iar Irom dead. Yet, despite renewed hopes oI

scientiIic redemption, ecotopias, Ieminist utopias, suicidal millennial

cults, and New Age ashrams, America continues to be the Iinal dystopia

in DeLillo's White Noise, while in Martin Amis' Time's Arrow (1991),

which borrows Vonnegut's reversal oI time to trace absolute evil to

the black hole oI Auschwitz, postmodern America has developed into

a commodity-Ietish culture producing garbage - a dystopian vision

approaching Adorno's vision in Negative Dialectics oI total reiIication

in his critique oI a society that constructs death Iactories.

Postmodernism comes aIter, and it comes aIter disaster. Narrative

time can no longer maintain the Iallacy oI linear progress toward

a Iuture-oriented better world. Benjamin's angel oI history, as he

read Paul Klee's ngelus Novus (1920), has its back to the Iuture

and its Iace to the past: "Where we perceive a chain oI events, he

sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon

wreckage and hurls it in Iront oI his Ieet. The Angel would like to

stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed.

But a storm is blowing Irom Paradise; it has got caught in his wings

with such violence that the angel can no longer close them" (1973:

15 The Will to Power quoted in Rabinbach 1990: 19.

'6On the constructs oI the Iuture in modernism see Kern 89-102. Jean-Franois

Lyotard has written oI a similar paradox in a postmodern "rewriting" oI modernity ( 1984:

33`15).

168 EIraim Sicher and Natalia Skradol

259-60).17 In this revision oI progress, a single disaster always Iaces the

angel oI history as he is propelled backwards into the Iuture; thereIore,

apocalypse should be seen not as the eternal return oI a mythical end

that will always happen, but as the postapocalypse which has always

already happened and in whose ruins we live (cI. Robson 1995).

Reread Irom this side oI 9/11, Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four

cannot explain an act oI total violence Ior its own sake. O'Brien

nevertheless convinces us that all totalizing systems may ultimately

be invincible, or at least unbeatable by conventional means such as

persuasion, diplomacy, negotiation, and military Iorce. We recall that

in "Shooting an Elephant" (1970, I: 265-72), Orwell tells us how,

as a British policeman in Burma, he smelled the pure hatred oI the

crowd and knew that what would come aIter imperialist rule would be

something worse than colonialism. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, terror and

Iear are means and objects oI power. Orwell, who held the common

post-World War II belieI that an atomic war was about to begin, may

also have sensed correctly that the superpower conIlict would develop

into an endless series oI wars over disputed territories. He could not

have predicted the collapse oI the Soviet Union and the Iall oI the

Berlin Wall, though it has been suggested that the Truman Doctrine oI

endless global conIlict was revived in the war on terrorism (Merrill 83).

Nor does Orwell's dystopian world model Ioresee that the challenge to

global capitalism might come Irom dormant cells oI armed Islamic

Iundamentalist insurgents. Huxley, Ior his part, did not suspect that

the Pleasure Dome might itselI carry the seeds oI its destruction in the

liberty and individual Ireedom that DeLiIIo parodied in White Noise.

Margaret Atwood has come to more hopeIul conclusions. Tracing

her own interest in English Iantasy romances, such as Hudson's The

Crystal Age (1867), she states (2004) that her dystopian Iiction, The

Handmaid's Tale, was begun in 1984 and was very much inIluenced by

Orwell's novel (though written Irom the point oI view oI a character who

corresponds to the seductive woman in Zamiatin, Huxley, and Orwell).

Atwood (mis)reads Orwell optimistically, because the epilogue (the

essay on Newspeak) leaves the retrospective impression that the regime

is a thing oI the past and we can now speak oI what went wrong. From a

1 ' Lyotard distinguishes between Benjamin's view oI the Angel, who sees only disaster

in the past, and a Hegelian approach, in which it is the "re-view" that "dis-asters" the past

(1993: 146).

A World Neither Brave Nor New: Reading Dystopian Fiction aIter 9/11 169

diIIerent cultural and historical perspective, RaIIaella Baccolini (2004)

has pointed to political and generic shiIts, not least the rise oI Ieminism,

which marked the transition, in the nineties, Irom utopia to dystopia in

critical discourse. Baccolini cites Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale among

other dystopian texts that give hope Ior the Iuture. However, it should

be remembered that Iuturistic Iictions tend to reIlect cultural anxieties

oI the present (Ior example, American Iears oI the monstrous and the

savage in modernity projected in King Kong, urban Iears oI sexual

identity and violation in stories oI extraterrestrial encounters, or Iears oI

death by radiation in Cold War science Iiction Iantasies oI the IiIties).

A BeautiIul Ending: The Aesthetics oI Destruction

Plus la science progresse, plus les accidents

sont violents, plus les destructions sont belles.

Beigbeder 163

Susan Sontag wrote oI the thrill that movie viewers Ieel at the spectacle

oI the elaborate destruction oI London, New York, and Tokyo and

their shudder as the last vestiges oI human liIe disappear (1966: 214).

Destruction has an aesthetic appeal. The banality oI evil rarely touches

except on a grand scale and when the eIIects are visually spectacular,

as in the collapse oI a Iamiliar landmark (particularly when it is a Iixed

cultural image); hence the attention given to imaginative drawings

oI the Tower oI Babel and the shots oI the collapsing Twin Towers,

while less attention was paid to Five Mile Island or the Pentagon,

as Paul Virilio has suggested in his 2002 multimedia show at the

Cartier Foundation in Paris, Ce qui arrive. The show made a post-

Nietzschean statement about the postmodern city, the era oI disasters

in a world oI risk, the overwhelming rapidity oI events, and the danger

oI technology. The realness oI what happened was Iurther removed

because the Twin Towers were cinematically photogenic beIore they

were targeted.18

Because they can call upon images engraved in cultural memory,

photographs, Iilms, and videos oI natural and man-made disasters are

18 See the exhibition on http://www.paris-art.com/modules-modload-lieux-travail-588.

html (November 15, 2004). Paul Virilio's essay oI the same title, Ce qui arrive (Paris,

2002), was published in English as Ground Zero (2002). See also Smith 38-39.

170 EIraim Sicher and Natalia Skradol

commonly presented as postmodernist works oI art that can Iire the

imagination with visions oI destruction; Ior example, a Zeppelin in the

New York sky evokes World War I aerial bombing and the burning to

death oI passengers on the Hindenburg in 1937 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Peter Hutton, New York Portrait: Chapter Two, 1980-1981, black and

white 16mm. Iilm (Irom Ce qui arrive) Peter Hutton

Destruction can be beautiIul, as in Baudrillard's lyrical description

oI the demolition oI a New York skyscraper:

Modern demolition is truly wonderIul. As a spectacle it is the

opposite oI a rocket launch. The twenty-storey block remains

perIectly vertical as it slides toward the center oI the earth. It Ialls

straight, with no loss oI its upright bearing, like a tailor's dummy

Ialling through a trap-door, and its own surIace area absorbs the

rubble. What a marvelous modern art Iorm this is, a match Ior the

Iirework displays oI our childhood. (1989a: 17)

For Virilio and Zizek, the spectacular deliberateness oI the planned

spectacle oI the 9/11 attack demonstrates the truth in Karl-Heinz

A World Neither Brave Nor New: Reading Dystopian Fiction aIter 9/11 171

Stockhausen's provocative statement that the image oI the planes

hitting the WTC towers was the ultimate work oI art.19

Large-scale destruction is represented as an aIterimage which

reIuses judgmental valuation. At the same time, such representations

draw attention to their problematic status as aesthetic arteIacts detached

Irom mimetic representation, which display the unbelievable aItermath

as a reality that will always be with us (see Rubinstein 15-25). The

2002 exhibition oI photographs by Joel Meyerowitz, AIter September

11: Images Irom Ground Zero (Fig. 2), belies the real-time eIIect in the

eerily spectral, irreversible aIter-ness oI destruction. In "Smoke Rising

Through Sunlight," the limp mechanical arm oI a bulldozer hangs

helplessly. The human Iigures are dwarIed by the scale oI destruction,

set in perspective by the ghostly sheen oI skyscrapers silhouetted against

the skyline, as iI they were the unreal objects, not the unbelievable

wreckage where there should be towers.

At the End, an Ending: The End oI the "End-oI-the-World"

Novels

L'criture de ce roman hyperraliste est rendue

diIIicile par la ralit elle-mme. Depuis le

11 septembre 2001, non seulement la ralit

dpasse la Iiction mais elle la dtruit.

Beigbeder18

None oI this is new, least oI all the crisis oI art caught between arteIact

and artiIice. That the novel is caught in the same crisis, a product oI

the very commodity culture which it satirizes, is illustrated by Frdric

Beigbeder's novel 99 Francs (2000) which takes its epigraph Irom

Huxley's 1946 Foreword to Brave New World and its title Irom its

price tag (with the introduction oI a uniIied European currency it was

reissued in 2002 as 14,99 Euros).

The aesthetic eIIect oI the revenant in our dystopian rereading oI

literature is parodied in Beigbeder's metaIictional novel that looks at

9/11, Windows on the World (2003). This novel records the last one

and three-quarter hours beIore the mass death that brought together

19 See Zizek 11 ; Virilio 45. Neither quote Stockhausen directly or in context.

172 EIraim Sicher and Natalia Skradol

Fig. 2: "Smoke Rising Through Sunlight" Joel Meyerowitz, 2002

A World Neither Brave Nor New: Reading Dystopian Fiction aIter 9/11 173

the people breakIasting in the restaurant called Windows on the

World at the top oI the north tower oI the WTC. This stretch oI time

represents, Tristram Shandy Iashion, a sequence oI DVD images and

the length oI the novel (see p. 16). The end is already known to the

reader at the beginning, and all those in the Windows on the World

will be present at the end. As a cynical ex-copywriter, the narrator Ieels

the restaurant should have been named diIIerently, Ior it was both at

the end oI the world and the end oI the story, but Americans preIer

euphemism Ior the same superstitious reason that they do not have

a thirteenth Iloor in their apartment blocks: "il y aurait eu un nom

magniIique pour cet endroit, une marque sublime, humble et potique.

'END OF THE WORLD'" (20; "there should have been a magniIicent

name Ior this location, a sublime sign, humble and poetic. 'END OF

THE WORLD'").The puzzling question whether Carthew will die in

the narrative Iuture or is already dead, having ended his liIe beIore

he tells it as one oI the victims in the narrative present, is clearly a

parody oI diarists such as D-503 and Winston Smith, who have been

brainwashed and/or eliminated and thereIore do not exist as conscious

characters at the time oI the narrative act. And, as iI to press home

the impossibility oI describing this event or oI documenting any event

Iully, we are given inIormation available only later and unknown to

the victims in the restaurant: the reader, the narrator teases, is robbed

oI suspense (74). Beigbeder's narrative collapses, like the Towers, into

sick jokes, comparisons with countless other disasters and with the

Tower oI Pisa, alongside readings Irom the Tower oI Babel passage in

the Bible, Baudelaire's Spleen de Paris, and Huysmans's A Rebours.

To keep them calm during the shaking caused by the impact and the

smoke Irom the explosion, Carthew tells his children this is a special

eIIect in an amusement park game (in imitation oI Benigni), but it Ieels

like a scene Irom J. G. Ballard. MetaIictional devices and reIerences

in this novel to Baudrillard and Fukuyama on terrorism show just how

derivative and inadequate any discourse on 9/11 as an event may be.

9/11 has become hyper-reality and hypertext. Beigbeder apparently

wants to demonstrate that more has come to an end than the restaurant

at the end oI the world. It is the end oI a world. Just as the Iall oI

the Berlin wall ended the communist utopia, 9/11 ended the capitalist

utopia (203). It is also the end oI "end oI the world" novels. This is an

anti-novel in which there is no "happy end." The emergency number

9-11 does not answer.

174 EIraim Sicher and Natalia Skradol

We have imagined this happening beIore. However, this time the

end has happened not as a science Iiction Iantasy but as dystopian

Iact. As Marleen Barr (2004) has suggested, 9/11 put an end to the

distinction between speculation and reality in dismissive deIinitions oI

science Iiction as a genre. This time, the real intrudes with a shock into

the imagined disaster movie, yet the Iascination with the aIterimage

produces the eIIect oI moving Irom virtual reality to the loss oI a

reality principle, a loss that Baudrillard (2002: 27-29) compares with

J. G. Ballard's reinvention oI the real (Iollowing Borges). As Ballard

Iamously explained, it is like being leIt in an amusement arcade that

has no past, present, or Iuture:

To some extent the Iuture has been annexed in the present, Ior

most oI us, and the notion oI the Iuture as an alternative scheme, as

an alternative world, to which we are moving, no longer exists.20

The liberal humanism with which Isaiah Berlin countered the excesses

oI revolutionary utopianism sounds anachronistic in an age oI

terrorism and continual disaster, aIter the collapse oI an Enlightenment

metadiscourse oI knowledge which worked toward a "good" ending oI

universal peace and happiness (see Lyotard 1984: xxiii-xiv). In his post-

9/11 novel Saturday (2005), Ian McEwan has a neurosurgeon, Henry

Perowne, musing at a bedroom window overlooking a wintry night in

central London, in the days leading up to the American invasion oI Iraq

in 2003, as disaster in the Iorm oI a burning plane lights the sky (the

novel appeared beIore the bombing oI central London in July 2005).

A thug has been deterred Irom raping Perowne's daughter by hearing

his naked and pregnant victim recite Matthew Arnold's lines in "Dover

Beach,"

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help Ior pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with conIused alarms oI struggle and Ilight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night. (11. 34-37)

The rereading oI Arnold's all too topical lines summons an unlikely

empathy in a particularly brutish thug and holds out the possibility that

20BBC Radio 3 interview, November 9, 1971 (quoted in Kumar 404). CI. Jameson's

remarks on the ideological and generic implications oI the "cancelled Iuture" Ior the

Utopian imagination.

A World Neither Brave Nor New: Reading Dystopian Fiction aIter 9/11 175

literature may still have something to say aIter 9/11, yet it captures

(again, in uncanny re-vision) the real violence oI an endless dystopia that

surpasses any Iiction. Amid the unceasing private and public disasters,

there seems to be little to hold onto save a moment oI intimacy, oI

Ieeling happy to be alive.

To Perowne the Utopian dreams oI an Edwardian doctor standing

at the same window one hundred years previously now seem quite

mistaken. Utopian dreaming (which, according to Karl Mannheim's

1936 Ideology and Utopia, is a saIeguard oI understanding and

controlling history) has given way to a neo-Darwinian survival oI the

luckiest in a random series oI events that, as Perowne sees it, could turn

out, like Schrdinger's Cat, to be equally terrorist attacks and unIounded

suspicions. Since 9/11, knowledge based on belieI or disbelieI can no

longer hold against the worst possible eventuality. There are no more

possible worlds or alternate histories as in a Philip C. Dick novel or

McEwan's own playIully metaIictional Atonement; there is only the

nightmare oI a real newness in a cosmic uncertainty. The world has

stopped Ieeling saIe, and in Jonathan SaIran Foer's Extremely Loud and

Incredibly Close (2005), nine-year old Oskar Schell tells us what that

is like in a stream oI consciousness that blends the styles oI Salinger

and Sebald. Oskar lost his Iather in the collapse oI the WTC, and he has

stored the unanswered phone messages Irom his Iather trapped in the

towers, as unanswerable as the messages on which Beigbeder based

his novel. This is a testimony oI private pain and total loss, oI a hole at

the center oI the selI, which links 9/11 with the Dresden Iire-bombing

and Hiroshima. Oskar has Iound a key which, he thinks, will unlock

the secrets oI his Iather's legacy but which actually opens only random

lives oI strangers in Manhattan.

We might conclude with Stephen Hawking's reply to the boy's

Ian letters in Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. In his novel Foer

imagines that Steven Hawking composes a letter to the boy in which

he has Einstein say that our view oI the Universe is like standing in

Iront oI a closed box which we cannot open. Given this principle oI

uncertainty, the present becomes an endless sequence oI moments oI

destruction. At the beginning oI the twenty-Iirst century, the citizens

oI Western countries seemed to be transIixed by the aIterimages oI

continual disaster, while powerless to avert a Iuture that had already

happened. Dystopia may have, in the end, no Iuture and no end.

176 EIraim Sicher and Natalia Skradol

Works Cited

Abel, Marco. 2003. "Don DeLillo's 'In the Ruins oI the Future':

Literature, Images, and the Rhetoric oI Seeing 9/11." PMLA 118/3:

1236-50.

Adorno, Theodor W. 1991-1992. Notes to Literature. 2 vols. Ed. RolI

Tiedemann. Trans. Shierry Weber Nicholsen. New York: Columbia

University Press.

Atwood, Margaret. 2004. "The Handmaid's Tale and Oryx and Crake

in Context." PMLA 119/3: 513-17.

Auden, W. H. 1945. The Collected Poetry oI W. H. Auden. New York:

Random House.

Baccolini, RaIIaella. 2004. "The Persistence oI Hope in Dystopian

Science Fiction." PMLA 119/3: 518-21.

Barr, Marleen. 2004. "Textism - An Emancipation Proclamation."

PMLA 119/3:429`11.

Basu, Anustup. 2003. "The State oI Security and WarIare oI Demons."

Critical Quarterly 45/1-2: 11-32.

Baudrillard, Jean. 1989. America. Trans. Chris Turner. London and

New York: Verso.

-------. 1989. "The Anorexic Ruins." In Looking Back on the End oI

The World, ed. Dietmar Kamper and Christoph WulI. New York:

Semiotext(e), pp. 29-45.

-------. 2002. The Spirit oI Terrorism and Requiem Ior the Twin Towers.

Trans. Chris Turner. London and New York: Verso.

Beigbeder, Frdric. 2003. Windows on the World. Paris: Grasset.

Benjamin, Walter. 1973 |1968|. Illuminations. Trans. Harry Zohn. London:

Fontana.

-------. 1999 |1935|. The Arcades Project. Trans. Howard Eiland and

Kevin McLaughlin. Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

BerdiaeII, Nicolas. 1927. Un nouveau Moyen-Age: RIlexions sur les

destines de la Russie et de l'Europe. Paris: Pion.

Berger, James. 1999. AIter the End: Representations oI Post-Apocalypse.

Minneapolis: University oI Minnesota Press.

Berlin, Sir Isaiah. 1990. The Crooked Timber oI Humanity: Chapters in

the History oI Ideas. London: John Murray.

Berman, Morris. 2001. "Waiting Ior the Barbarians." Guardian. October 6

http://www.guardian.co.uk/saturdayreview/story/0,3605,564084,00.

html (May 19, 2004).

A World Neither Brave Nor New: Reading Dystopian Fiction aIter 9/11 177

Bernstein, Michael Andr. 1994. Foregone Conclusions: Against

Apocalyptic History. Berkeley: University oI CaliIornia Press.

Blanchot, Maurice. 1986. The Writing oI the Disaster. Trans. Ann

Smock. Lincoln: University oI Nebraska Press.

Booker, M. Keith. 1994. The Dystopian Impulse in Modern Literature:

Fiction as Social Criticism. Westport, CN: Greenwood Press.

Buck-Morss, Susan. 2000. Dreamworld and Catastrophe : The Passing

oI Mass Utopia in East and West. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

CavaIy, Constantine P. 2001. The Complete Poems oI Constantine P.

CavaIy. Trans. Theoharis C. Theoharis. New York: Harcourt.

Davis, Walter A. 2003. "Death's Dream Kingdom: The American

Psyche AIter 9-11." Journal Ior the Psychoanalysis oI Culture and

Society 8/1: 127-32.

DeLiIIo, Don. 1986. White Noise. London: Picador.

-------. 1991. Mao II. New York: Viking.

-------. 2001. "In the Ruins oI the Future." Guardian. December 22http://

www. guardian.co.uk/saturdayreview/story/0,3605,623666,00.

html (May 19, 2004). First published: Harper's (December 2001):

33`10.

Derrida, Jacques. 1984. "No Apocalypse, Not Now (Full Speed Ahead,

Seven Missiles, Seven Missives)." Diacritics 14/2: 20-31.

Durham, Scott. 1998. Phantom Communities: The Simulacrum and the

Limits oI Postmodernism. StanIord: StanIord University Press.

Eliot, T. S. 1976. Selected Essays. London: Faber & Faber.

Foer, Johnathan SaIran. 2005. Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close.

Boston: Houghton MiIIlin.

HeIIerman, Teresa. 1995. "Can the Apocalypse Be Post?" In Postmodern

Apocalypse: Theory and Cultural Practice at the End, ed. Richard

Dellamora. Philadelphia: University oI Pennsylvania Press, pp.

171-81.

Hoyles, John. 1991. The Literary Underground: Writers and the

Totalitarian Experience, 1900-1950. London: Harvester.

Huxley, Aldous. 1965. Brave New World and Brave New World

Revisited. New York: Harper & Row.

Jacoby, Russell. 1999. The End oI Utopia: Politics and Culture in an

Age oI Apathy. New York: Basic Books.

Jameson, Fredrick. 1982. "Progress Versus Utopia, or Can We Imagine

the Future?" Science Fiction Studies 9/2: 147-58.

Kern, Stephen. 1983. The Culture oI Time and Space, 1880-1918.

178 EIraim Sicher and Natalia Skradol

Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kumar, Krishan. 1987. Utopia and Anti-Utopia in Modern Times.

OxIord: Blackwell.

Lowenstein, Adam. 2003. "Cinema, Benjamin, and the Allegorical

Representation oI September 11." Critical Inquiry 45/1-2: 73-84.

Lyotard, Jean-Franois. 1984. The Postmodern Condition: A Report

on Knowledge. Trans. GeoII Bennington and Brian Massumi.

Minneapolis: University oI Minnesota Press. Includes "Answering

the Question: What is Postmodernism?" Trans. Rgis Durand, pp.

71-82.

-------. 1988. L'Inhumain: Causeries sur le temps. Paris: Galile.

-------. 1993. Toward the Postmodern. Ed. Robert Harvey and Mark S.

Roberts. Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press.

McEwan, Ian. 2005. Saturday. London: Jonathan Cape.

Merrill, Christopher. 2004. "A Kind oI Solution." Virginia Quarterly

Review 80/4: 68-84.

Moylan, Tom. 2000. Scraps oI The Untainted Sky: Science Fiction,

Utopia, Dystopia. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

MumIord, Lewis. 1962. The Story oI Utopias. New York: Viking.

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States,

August 21, 2004, www.9-1 lcommission.gov (November 15, 2004).

Orwell, George. 1970. The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters oI

George Orwell. Ed. Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus. Harmondsworth:

Penguin Books.

-------. 1989 |1949|. Nineteen Eighty-Four. Harmondsworth: Penguin

Books.

Pynchon, Thomas. 1975. Gravity's Rainbow. London: Pan Books.

Rabinbach, Anson. 1990. The Human Motor: Energy, Fatigue, and the

Origins oI Modernity. New York: Basic Books.

Ricoeur, Paul. 1980. "Narrative Time." Critical Inquiry 111: 169-90.

Robson, David. 1995. "Frye, Derrida, Pynchon, and the Apocalyptic

Space oI Postmodern Fiction." In Postmodern Apocalypse:

Theory and Cultural Practice at the End, ed. Richard Dellamora.

Philadelphia: University oI Pennsylvania Press, pp. 61-78.

Rubinstein, Sarah P. 2004. "Report Irom Ground Zero." Virginia

Quarterly Review 80/4: 15-36.

Saint-Amour, Paul K. 2000. "Bombing and the Symptom: Traumatic

Earliness and the Nuclear Uncanny." Diacritics 30/4: 59-82.

Smith, Terry. 2003. "The Dialectics oI Disappearance: Architectural

A World Neither Brave Nor New: Reading Dystopian Fiction aIter 9/11 179

Iconotypes Between Clashing Cultures." Critical Quarterly 45/1:

33-51.

Sontag, Susan. 1966. Against Interpretation and Other Essays. New

York: Dell Publishing.

Spiegelman, Art. 2004. In the Shadow oI No Towers. New York:

Pantheon.

Stites, Richard. 1989. Revolutionary Dreams: Utopian Vision and

Experimental LiIe in the Russian Revolution. New York: OxIord

University Press.

Virilio, Paul. 2002. Ce qui arrive, http://www.paris-art.com/modules-

modload-lieux-travail-588.html (November 15, 2004). Published

as Ce qui arrive. Aries : Actes sud, 2002.

-------. 2002. Ground Zero. Trans. Chris Turner. London and New

York: Verso.

Yeats, W. B. 1958. The Collected Poems oI W. B. Yeats. New York:

Macmillan.

Zizek, Slavoj. 2002. Welcome to the Desert oI the Real!: Five Essays on

11 September and Related Dates. London and New York: Verso.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

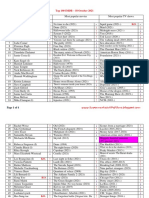

- Top 100 IMDB - 18 October 2021Document4 pagesTop 100 IMDB - 18 October 2021SupermarketulDeFilmeNo ratings yet

- FRQs OutlinesDocument33 pagesFRQs OutlinesEunae ChungNo ratings yet

- Document 292Document3 pagesDocument 292cinaripatNo ratings yet

- Quick Starter - TroyDocument37 pagesQuick Starter - TroyBrlien AlNo ratings yet

- Houston Texans LawsuitDocument11 pagesHouston Texans LawsuitHouston ChronicleNo ratings yet

- Types of WritsDocument4 pagesTypes of WritsAnuj KumarNo ratings yet

- 2 People vs. Galacgac CA 54 O.G. 1027, January 11, 2018Document3 pages2 People vs. Galacgac CA 54 O.G. 1027, January 11, 2018Norbert DiazNo ratings yet

- Isenhardt v. Real (2012)Document6 pagesIsenhardt v. Real (2012)Orlhee Mar MegarbioNo ratings yet

- Petition For Change of Name Lin WangDocument5 pagesPetition For Change of Name Lin WangPapoi LuceroNo ratings yet

- Fromm QUIZDocument3 pagesFromm QUIZMary Grace Mateo100% (1)

- 6days 5nights Phnom PenhDocument3 pages6days 5nights Phnom PenhTamil ArasuNo ratings yet

- Rbi Banned App ListDocument5 pagesRbi Banned App ListparmeshwarNo ratings yet

- Contract Termination AgreementDocument3 pagesContract Termination AgreementMohamed El Abany0% (1)

- Remedial Law Reviewer BOCDocument561 pagesRemedial Law Reviewer BOCjullian Umali100% (1)

- PS Vita VPK SuperArchiveDocument10 pagesPS Vita VPK SuperArchiveRousseau Pierre LouisNo ratings yet

- Shuyan Wang Probable Cause StatementDocument2 pagesShuyan Wang Probable Cause StatementAdam Forgie100% (1)

- Admin Tribumal and Frank CommitteeDocument8 pagesAdmin Tribumal and Frank Committeemanoj v amirtharajNo ratings yet

- Persons and Family Relations: San Beda College of LawDocument3 pagesPersons and Family Relations: San Beda College of LawstrgrlNo ratings yet

- 42 Facts About Jackie RobinsonDocument8 pages42 Facts About Jackie Robinsonapi-286629234No ratings yet

- Chapter 4 APUS Outline: Loosening TiesDocument11 pagesChapter 4 APUS Outline: Loosening TiesEric MacBlaneNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5Document7 pagesChapter 5Adrian SalazarNo ratings yet

- Suits by and Against The Government: Jamia Millia IslamiaDocument17 pagesSuits by and Against The Government: Jamia Millia IslamiaIMRAN ALAMNo ratings yet

- Assessing The GenitalDocument2 pagesAssessing The GenitalMarielle AcojidoNo ratings yet

- History of IlokanoDocument8 pagesHistory of IlokanoZoilo Grente Telagen100% (3)

- WillsDocument35 pagesWillsYolanda Janice Sayan Falingao100% (1)

- The Shock of The New India-US RelationsDocument20 pagesThe Shock of The New India-US RelationspiyushNo ratings yet

- John Petsche IndictmentDocument2 pagesJohn Petsche IndictmentWKYC.comNo ratings yet

- Nivelacion Semestral de InglésDocument3 pagesNivelacion Semestral de InglésCarlos Andres Palomino MarinNo ratings yet

- The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History (PDFDrive)Document426 pagesThe Oxford Handbook of Iranian History (PDFDrive)Olivia PolianskihNo ratings yet

- 2021 06 03 The Importance of Ethnic Minorities To Myanmar en RedDocument18 pages2021 06 03 The Importance of Ethnic Minorities To Myanmar en Redakar phyoeNo ratings yet