Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Assessment

Uploaded by

may monCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Assessment

Uploaded by

may monCopyright:

Available Formats

Creating possibilities through research

ARTICLE INFO Article history Received January 14, 2010 Accepted February 9, 2010 Refereed anonymously

HongKongprincipalsperceptionsonchangesin evaluationandassessmentpolicies: Theyrenotforlearning

Ming Yan Ngan1, John Chi-Kin Lee2, Gavin T. L. Brown1

1

The Hong Kong Institute of Education 2 Chinese University of Hong Kong

ABSTRACT. Hong Kong has introduced new school evaluation and assessment policies since 1997 which need to be implemented by school leaders. This context creates the possibility that policy intentions are not understood, accepted, or implemented. Using discrepancy evaluation analysis, this study reports interviews from 23 Hong Kong school principals about their perceptions and experiences of new policies to do with school evaluation and assessment for learning. The discrepancies fell into five major categories: one size does not fit all; a matter of school survival; workload for teachers; time pressures on those who manage and teach; and learning environment at the schools. The school principals were not convinced that the intended outcomes of helping schools to improve learning were achieved, rather they believed the policies were being implemented to control and close schools unfairly.

Keywords: evaluation and assessment policy, principal, discrepancy, qualitative research.

INTRODUCTION

*Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Ming Yan Ngan . Electronic mail may be sent via internet to myngan@ied.edu.hk

In Hong Kong, many educational changes and innovations have been initiated in the last decade related to school quality (Education Commission, 1997), curriculum (details see Ngan & Lee, 2008; Lee, Yin, & Zhou, 2008), teaching (details see Li & Ngan, 2009), school system (Education Commission, 2000), and school evaluation and student assessment (details see Pang, 2000, 2005; Wu & Tang, 2004; Wu, 2001, 2002). In this paper, we focus on recent changes to policies on school evaluation and student assessment as perceived by school principals. Hong Kong School Evaluation Policy Changes The Hong Kong Education Commission (1997) shifted responsibility for school quality policy from central authorities to schools, by promoting internal quality assurance through school-based management, participation of parents and teachers, and school self-evaluation. This devolution of responsibility, part of Asian region trend (Kennedy & Lee,

36

Copyright 2010 Philippine Society for Educational Research and Evaluation

Asian Journal of Educational Research and Synergy 2(1) , May 2010

HONG KONG PRINCIPALS PERCEPTIONS ON CHANGES IN EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT POLICIES

2010; Lee, Ding, & Song, 2008; Peng & Lee, 2009), have made school leaders responsible for school-based improvements. The Hong Kong Education Bureau (EDB) is responsible for the school assurance policy and for validation of the School Self-Assessment (SSA). The EDB conducts an External School Review (ESR) to validate the school-based evaluation (Lee, 2009). Before conducting SSA and ESR, schools produce their own school plans and school report for their stakeholders. The plans include school-based statement of aims and developmental focus objectives. School self-assessments are pursued and carried out every three to five years in accordance with the EDB quality assurance framework, performance indicators, and school selfevaluation tools. Thus, school leaders are now responsible for tasks previously carried out by external education inspectors or education department bureaucrats. Even though the SSA is not every year, the process appears to require a substantial by the school leaders and teachers. Hong Kong Student Evaluation Policy Changes Further devolution of responsibility to schools can be seen in the Hong Kong policy changes around student assessment. The EDB has introduced, consistent with global trends (Newton, 2000), an assessment for learning (AfL) policy to mitigate the negative effects of over-reliance on public examinations. AfL requires schools to implement a much more labour intensive set of assessment practices (e.g., give constructive feedback, share learning objectives, and assess higherorder thinking skills) oriented towards improved classroom teaching and learning. Chan, Kennedy, Yu & Fok (2006, p.6) have argued that the shift of the new assessment reform is dramatic in terms of goals, content, method and the type of feedback for students. Thus, school leaders are responsible for a much

Asian Journal of Educational Research and Synergy 2(1) , May 2010

more complex school-based assessment practice rather than simply relying on in-house or public end-of-year examinations to determine what students have learned. Impact on School Leadership The evaluation and assessment policy changes made in Hong Kong have been introduced in the hope of improving school effectiveness (Creemers, 2002). However, it should be clear that the assessment and school evaluation reforms require a significantly different approach to teaching, learning, and school leadership. Hong Kong school leaders now play a key role in implementing assessment and evaluation policies and in facilitating professional development opportunities for their teachers. The introduction of these policies has been predicated on the assumption that school leaders are able to cope with these devolved and increased responsibilities. The goal of this study is to examine how these challenges have been handled by school principals and to identify any discrepancies or gaps between policy intention and principals perceptions and understandings of the policy implementation. The research question for this study was what discrepancy, if any, is there between the EDB policies on school selfassessment and assessment for learning and implementation in Hong Kong schools?

METHODOLOGY

This study uses the discrepancy evaluation model (Steinmetz, 2000) to examine discrepancies between what should be according to the government policies for school self-evaluation and assessment for learning and how those policies are actually achieved. The model then requires an evaluative judgment about the worth or adequacy of the policies based on the discrepancy information.

37

MING YAN NGAN, JOHN CHI-KIN LEE and GAVIN T. L. BROWN

Discrepancy evaluation requires that the informants be expert in the provision of information about how the object being evaluated should be implemented and how it is actually being implemented. In this case, a sample of Hong Kong school principals are used as expert sources because they know what the policies intended and how they were actually being implemented in their own schools. Prior to the field research, the EDB policy documents (assessment for learning in CDC, 2001, 2002 and school evaluation in Education Commission, 1997) were studied to ensure that the intended goals were accurately understood and to draft questions for the principal interviews. The school principals interviewed in this study were purposefully selected. A list of 18 potential interviewees was drawn systematically from principals who had participated in Bryant et al. (2003) study. Stratification was used to ensure that the list had schools from all 18 districts of Hong Kongs school system, came from all academic performance bands, and that the principal was sufficiently experienced to be considered expert about these policies. All 18 invitees agreed to participate and using snow ball strategies an additional five principals were added to the sample. More than half of the principals had actively participated in various EDB committees which had contributed to the formulation of educational policies. Hence, a total of 23 of principals (14 primary, 9 secondary) participated in the interviews which were conducted in Cantonese and taperecorded. Interviews lasted between 45 minutes and two hours. Hoffman (1995, p.143) identified in-depth interviewing as being particularly appropriate for policy research, commenting that qualitative interviews served to uncover and understand as far as possible the specific

rationality and the self view of the actors involved. Open-ended interviewing has been shown to be particularly successful with pertinent people (Kennedy & OConnor, 1999). Following Morrissey (1970, p.111), the interviewer let the respondents talk.let him run with the ball. A semi-structured question schedule was used to facilitate the interviews. The questions were: 1) What is the discrepancy (if any) between the EDB school evaluation and assessment policies and your school? 2) Some academics have suggested that there is a gap between policy reformers and those that actually implementing the change. Has this problem materialized at your school? How and why? 3) Did you consider the pros and cons of the school-based assessment policies in light of the new school evaluation and assessment polices, and if so how and what are your conclusions? More than half of the principals chose to validate the transcriptions of their interviews. The policy documents and interviews were analysed using NVivo 7 (2006). Coding categories and themes were based on the key aspects of the relevant EDB policy documents. An inductive analysis approach was employed to categorize the principal interview data (Patton, 1990). The data was also analyzed to identify key issues and problems generated by the policies. Special attention was paid to: a) principal perceptions and beliefs; b) principal interpretations of the policies; c) any policy adoption or adaptation at the school-level; and d) the discrepancy between the school and the system policy identified by the principals. Direct quotations from the principal interviews, shown in italics, are referenced according to research question, category code and sub-code, principal identification, and section identification. Hence, code Q4_1.1_S3c means

Asian Journal of Educational Research and Synergy 2(1) , May 2010

38

HONG KONG PRINCIPALS PERCEPTIONS ON CHANGES IN EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT POLICIES

research question 4, code 1, sub-code 1, secondary principal #3, section #3 for this principal. Note that all analysis was done on the Chinese transcripts and translations for this manuscript were carried out by the first author.

RESULTS

all did not start from the same starting point. Nevertheless, only one ruler now measures us. How could the result be measured Q4_1.1_S3c.

Five major categories were used to make sense of the discrepancies principals reported between the intended outcomes of the policies and the actualities they experienced in their schools. These were, in descending order of importance: one size does not fit all; a matter of school survival; unbearable workload for teachers; from joyful learning to drilling; and limited time and space to cater for diversity. One size does not fit all In this study, most of the principals had negative views about the school quality assurance policy and processes. They perceived that EDB strived for school accountability via the application of the School Self Evaluation (SSE) and External School Review (ESR) policy processes. Seventeen of the principals perceived that the SSE and ESR did not provide a fair and accurate assessment of school accountability. The key reason for this perception lay in the narrow and limited set of criteria used to evaluate schools and which were considered not to be sensitive to the unique features and characteristics of each school in relation to its teachers, students, and their ecological contexts. The majority of respondents believed the SSE & ESR policies did not consider school contexts and the change processes in each school. One principal said:

Schools have their own unique historical backgrounds, are able to react and respond to change more rapidly than others. Some may run first, and some may run slow, but we

He further claimed, Why cant each school have its own agenda, culture, characteristics? Why is it necessary to follow the only one method? (Q4_1.1_S2c). Another principal stated, the student intake quality is ignored. They would not care if you are cooking a fresh or a dead fish; they just examine what you have cooked (Q4_1.1_S10g). He went on with the dead fish metaphor: No matter how well you can cook, dead fish smells bad (Q4_1.1_S10f). The principals perceived the quality assurance mechanism was unfair to schools as the governments mechanism was a one-size-fitsall criterion. It was result-oriented, it ignored the student intake quality, the school background, and the significant variations in student capabilities (academic banding); thus, forcing schools to abandon their normal ways of operation. Some schools had no choice and could only follow the official requirements. The principals felt extreme stress with respect to the SSE and ESR results. For most of the principals, the education reform was full of contradictions. On the one hand, school-based management was promoted, but on the other hand, school administration was strictly controlled by the EDB. As one principal reflected:

In fact, we are very proactive in developing our school, and we are now having some positive outcomes. All of a sudden, we are told to stop what we are developing, and we are required to develop what has been planned for us. Q4_1.2_S5a

He went onto state: We have to give up our harvest, and use the instruments provided by EMB [now EDB]. We are not ready to accept the change (Q4_1.2_S5b). Thus, we conclude that instead of empowering schools, the EDB

39

Asian Journal of Educational Research and Synergy 2(1) , May 2010

MING YAN NGAN, JOHN CHI-KIN LEE and GAVIN T. L. BROWN

policy on SSA and ESR is insensitive to the complex variation in school needs and issues which affect improvement and effectiveness. A Matter of School Survival A common concern expressed by the principals focused not so much on their schools ability to implement the policies, but rather on the ultimate survival of their school. In Hong Kong, school evaluation is equated with the perceived quality of education a school offers. The current EDB policy of funding schools only considers schools that can attract at least 23 Primary 1 (Grade One) pupils. If any school fails to enrol at least 23 Primary 1 pupils for three years in a row, the government will close the school. Competition for school applicants was becoming more intense as the school-age population declined. The interviewed principals were worried about their schools being assessed as under-performing or performing unsatisfactorily which could lead to a drop in enrolment and ultimately closure. The principals felt that the threat of school closure was being packaged in the name of educational quality enhancement. One principal expressed this concern: I am afraid that if all schools in Hong Kong are doing the marketing and promotion in order to survive, then educational quality will be damaged (Q4_2.3_P11c). Another principal endorsed that comment: If a school performs poorly, then student intake, teachers and parents would also be influenced detrimentally (Q4_1.2_S10a). It would appear that, instead of helping schools improve, the SSA and ESR policies, at a time of falling school-age populations, was seen as a back-door attempt to cut costs and reduce the number of schools in the system. Hence, there is a considerable discrepancy between intended and implemented consequences for the school self-assessment policy.

Unbearable Workload for Teachers The principals indicated they had to use energy and time to deal with excessive accountability and intense competition. Since the SSA and ESR reviews focused on teaching and learning, school management and leadership, implementation of systemic assessment policy was also part of the process. Most Hong Kong schools tended to over-document their school reports and organize school promotional activities. Even more of concern to the principals were the implications for their staff. More than half (61%) of the principals pointed out that their teachers were under pressure with respect to workloads. The principals indicated that many teachers were on the verge of psychological and emotional crisis because of dealing with the new assessment policy and other associated initiatives. This perception echoed Chengs (2004) report that Hong Kong teachers were working about 67 hours per week, far more than other Chinese cities. Despite the new policys emphasis on mutual trust and collaboration among teachers, professional autonomy, gaining confidence through rapport, and avoiding fragmentation and overloading, the principals suggested that these practices ultimately created excessive workload and unnecessary stress for both teachers and students. In addition to teaching, teachers had to be involved in school administrative work, participate in ongoing education courses for upgrading their qualifications, as well as organizing extra-curricular activities after normal teaching working hours. The teachers belonged to numerous committees and groups within their school, each with its own set of responsibilities, thus adding to their workload. In responding to the systems new assessment policies, there were additional requirements with regard to more collaborative teamwork

40

Asian Journal of Educational Research and Synergy 2(1) , May 2010

HONG KONG PRINCIPALS PERCEPTIONS ON CHANGES IN EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT POLICIES

both in and out of classrooms and an increase in the number of staff meetings. The role of teachers in change and reform processes is an important priority of these new policies and is also advocated by most change analysts (e.g., Cheng, 2004; Fullan 1992, 2000; Fullan & Hargreaves, 1992). During the implementation of the new assessment policy, all Hong Kong English language teachers had to also meet new benchmark language standards mandated by the EDB in the name of school quality. As one principal said, I think teachers are all hard-working. The sequel of continuing this reform is that all of us will burn out! (Q3_D2_S9b). The same principal also expressed concerns about non-teaching work and its impact on his schools survival:

In fact we understand clearly that we are not engaging in our honest work, its ridiculous. Teaching is work, which a teacher should devote oneself to as it influences students directly. But we have to handle a lot of administration work and many superficial documents. Why should we hang a banner? For advertising? We might feel suffocated because of excessive reforms. How much time then could be left for teaching preparations? (Q3_D2_P7a)

effective, creative and committed learning. Joyful learning has become a core value:

The reason for the emphasis on learnerfocused and joyful learning is that only when students enjoy learning, and are motivated by their own initiatives, can their potential be fully developed (Law, 2004).

The new systemic evaluation and assessment policies did not recommend rote learning or drilling. However, 28% of participating primary school principals indicated that their schools used drill exercises to help their students achieve better assessment results. Some principals were unwilling to abandon drilling as their response to examinations because they considered drilling as means of fulfilling their responsibility to students and as a of personal job survival. A principal stated,

I think it is necessary to prepare the students for the test. For example, we [have the students] practice what have to be learnt with some writing exercises, so that they can get familiar with the format of the test (Q4_7.0_P7a).

In many public speeches, EDB officials responded that the reforms were not intended to increase workload (see Lai, 2005). Unfortunately, the principals were seriously concerned about the workload implications of the new assessment policy. The principals considered that the evaluation and assessment policies did not offer alternative workload adjustment schemes in devolving massive responsibilities to the school level. From Joyful Learning to Drilling One of the goals of the education reform agenda in Hong Kong was to promote joyful,

Asian Journal of Educational Research and Synergy 2(1) , May 2010

Another principal endorsed this: We are in a hurry to re-arrange the time-table; we hold the normal lessons and only concentrate on drilling, like visual and audio practice and oral discussions (Q4_7.0_P5a). One principal expressed some regret for this emphasis on test preparation: I feel sorry for the students that I was too late to prepare them for the test format. I have had to arrange a month for the drillings (Q4_7.0_P5b). Another principal accepted the need to prepare his students,

We have spent more time on adapting to the writing test, explaining it to the teachers, analyzing the topics, and thus relatively less time is spent on everyday teaching, and our students also think that this arrangement is no good (Q4_7.0_P7d).

41

MING YAN NGAN, JOHN CHI-KIN LEE and GAVIN T. L. BROWN

The EDB policy about new formative assessments (i.e., Basic Competence Assessment) and the new school evaluation tests (i.e., Territory-wide School AssessmentTSA) is that they are low stakes designed to help teachers and schools improve student learning. The TSA is administered in Grades 3, 6, and 9 across all Hong Kong schools to identify schools requiring assistance to raise student performance in English, Chinese, and mathematics. A goal of the new assessments was to reduce drilling and memorizing strategies that prevalent in Hong Kong schools. However, some principals indicated that they had introduced after-school tutorials for Grade 2 pupils to support their preparation for the TSA in Grade 3, and intensive training programs for Grade 6 students. Furthermore, the principals perceived that the TSA school evaluation assessments were highstakes rather than low-stakes. They believed that the TSA results would be one factor in determining their schools survival. They believed EDB would use the system level assessment data to punish rather than assist schools that had unsatisfactory results. Almost all participating principals believed EDB would not make use of the results for schools improvement purposes. While EDB has advocated joyful learning, the principals were aware that EDB was still using School Self Review, External School Evaluation, Quality Assurance Report, and Student Assessment Public Examination results to monitor school quality. Our principals believed the outcomes of the new assessment policy were being used by EDB as high-stakes indicators for schools. While the EDB policy is to evaluate and assist weak schools, Madaus (1988) reminds us that as long as individuals believe that assessments are important, then it does not matter what the official purpose is. Where school principals believe outcomes of school assessments

Asian Journal of Educational Research and Synergy 2(1) , May 2010

determine the continuing existence of their schools, a siege mentality may develop and undermine innovative pedagogy. The assessment policy initiated by the Hong Kong government, as perceived by these principals, does not exhibit or support joyful learning, and as Madaus (1988) pointed out such nonalignment would ultimately restore a culture of excessive and mechanical drills. One principal commented that he refused to return to drilling even though many schools had done so, I am not sure if it is caused by school closures, but many schools are so frightened that they have restored drillings for learning on the part of the students (Q4_7.0_P10a). These drilling approaches would seem to be incompatible with the concept of joyful learning. Catering for Student Diversity One of the reasons the EDB wanted schools to implement the AfL policy was to support formative assessment for a diverse student body. Whereas, only 5% of Hong Kong students are not ethnic Chinese, there is a great diversity of academic ability that has to be addressed in schools, despite the academic banding system. One principal believed that the tight schedules to finish subject syllabi, regular tests and examinations, more than 30 students in a class, and short lesson times (i.e., 40 minutes) meant there was little time and room to cope with student diversity. Thus, some schools were providing after-school tutorials for all students regardless of ability, meaning that less individualised help was being provided to exceptional children. This problem was especially difficult in primary schools which only operated for half-days (approximately 510% of schools at the time of this study); one principal commented because we are morning classes, time is even more limited (Q4_4.0_P14b). He further claimed, we have no rooms, the afternoon classes have to take up all the rooms (Q4_4.1-P14g) therefore we have

42

HONG KONG PRINCIPALS PERCEPTIONS ON CHANGES IN EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT POLICIES

refitted a pantry to be an after-school tutorial room (Q4_4.1_P14d). These responses are indicative of the principals difficulties in getting enough resources to deal with student diversity as per the policy objectives. Our respondents plainly viewed catering for learner differences was merely a luxury in the new terrain of assessment policies.

DISCUSSION

in an education system like Hong Kong, accountability and performance are highlighted, which may induce stress to teachers and school resistance to the adoption of evaluation measures. Also, the cultural heritage emphasizing academic excellence in Hong Kong may exacerbate competitiveness among students, teachers and schools, defeating the good intentions of evaluation (such as in the case of TSA and school self-evaluation) in providing feedback for improvement. (Lee, 2009, p. 68)

This study used interviews to collect principal perceptions of the Hong Kong school evaluation and assessment for learning policy initiatives. Discrepancy evaluation analysis was conducted to analyze the differences between intended and implemented outcomes of these major policy initiatives. Out analysis shows that principals perceived the policies as instruments of control and criteria leading to possible closure of their schools. They believed the EDB is promoting a one-size-fit-all policy, which was unfair to the complexity of school contexts and which appeared to be a mechanism by which schools could be closed. Principals perceived their teachers as facing an unbearable workload in coping with the new policies and, regretfully, were resorting to drilling methods to meet competitive pressures to maximize student scores. Not only was joyful learning being squeezed out, but principals indicated that schools did not have space and time to meet the needs of created by student diversity or meet learner differences. We conclude that our respondents felt oppressed by policies which, in reality, differed greatly from their intended goals. The policies were not seen as enhancing learning, but rather as creating even greater concerns about the survival needs of schools. These findings echo Lees observation that,

The principals qualms about the policies reflect a serious problem in Hong Kong. Mutual trust between EDB and schools seems to be tremendously undermined. In the absence of mutual trust between these parties, it is difficult to see any good emanating from the implementation of such well-intended evaluation and assessment policies. Unfortunately, the principals perceived that school quality assurance and improvement mechanism was one of the dominant factors in determining school survival and recruitment of new students. The respondent principals knew they must work hard in dealing with the quality assurance process; however, they saw this as survival not improvement. Despite consultative processes used in Hong Kong to develop new policies, this study suggests that school principals had the impression that the policies had been dreamed up in a locked room filled only with bureaucrats. This sense of disempowerment and detachment from the policy is of great concern in achieving schooling improvement. What may be needed is not so much new rounds of consultation, but rather a much slower pace of reform that disentangles issues arising from the current decreasing school age population. A renewed working relationship between EDB officials and school leaders seems to be needed if education reforms are to succeed.

Asian Journal of Educational Research and Synergy 2(1) , May 2010

43

MING YAN NGAN, JOHN CHI-KIN LEE and GAVIN T. L. BROWN

This study indicates further research is needed to better understand conditions under which educational reforms to do with assessment can be implemented in a more constructive fashion. The New Zealand experience with introducing a new electronic assessment system similar to the Basic Competency Assessment system clearly showed the importance of involving teachers and taking an evolutionary developmental process rather than a rapid topdown approach (Hattie & Brown, 2008). Research into teacher and school leader beliefs about the nature and purpose of school assessment and evaluation may assist in understanding the context better in which EDB policies have to be implemented. Recent research has indicated that Hong Kong teachers are strongly committed to using assessment for improvement but this belief was opposed to using assessment to demonstrate school quality (Brown, Kennedy, Fok, Chan, & Yu, 2009). A richer understanding of how teachers and school leaders conceive of assessment may lead to better policy design and implementation. As long as governments depend on school leaders and teachers to implement policies that potentially have negative consequences for schools or which are perceived as having negative consequences, the understandings of principals and teachers will matter. This study contributes to identifying serious policy implementation problems in introducing school evaluation and assessment policies. More importantly, the study points out possible solution paths for the discrepancies provided both policy makers and policy implementers are involved.

REFERENCES

Brown, G., Kennedy, K., Fok, P., Chan, J. & Yu, W. (2009). Assessment for improvement: Understanding Hong

Asian Journal of Educational Research and Synergy 2(1) , May 2010

Kong teachers conceptions and practices of assessment. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 16(3), 347-363. Bryant, S., Timmis, A., Fok, P., Berry, S. & Ngan, M. (2003). Assessment for Learning: Formative Assessment Strategies Used in the Classroom of Hong Kong (Improving Assessment by Transforming Assessment). (unpublished report) Hong Kong: HKIEd Internal Research Grant, 2003-2004. Chan, K., Kennedy, K., Yu, W. & Fok, P. (2006). Technical Paper No.2, Assessment policy in Hong Kong: Implementation issues for new forms of assessment. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Institute of Education & Quality Education Fund. Cheng, Y. C. (2004). The school system reform: Success or failure conditions. Unpublished manuscript, Asia Pacific Educational Leadership and School Quality Centre, Hong Kong Institute of Education. Creemers, B. (2002). From school effectiveness and school improvement to effective school improvement: Background, theoretical analysis, and outline of the empirical study, Educational Research and Evaluation, 8(4), 343 362. UK: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. Curriculum Development Council. (2001). Learning to Learn: The Way Forward in Curriculum Development Hong Kong: Curriculum Development Council. Curriculum Development Council. (2002). Basic Education Curriculum Guide: Building on Strengths. Hong Kong: Curriculum Development Council. Education Commission. (1997). Education Commission Report No. 7. Hong Kong Government Printer. Education Commission. (2000). Review of

44

HONG KONG PRINCIPALS PERCEPTIONS ON CHANGES IN EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT POLICIES

Education System: Consultation on Proposals for Education Reform. Hong Kong, China: Author. Fullan, M. (1992). Successful school improvement: the implementation perspectives and beyond. U.K.: Open University Press. Fullan, M. (2000). Change forces. Keynote speech in the International Congress for School Effectiveness and Improvement, 4-8 January 2000, Hong Kong: The Hong Kong Institute of Education. Fullan, M. & Hargreaves, A. (1992). Teacher development and education. London; Washington, D.C.: Falmer Press. Hattie, J. & Brown, G. (2008). Technology for school-based assessment and assessment for learning: Development principles from New Zealand. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 36 (2), 189-201. Hoffman, J. (1995). Implicit theories in policy discourse: An inquiry into the interpretations of reality in German technology policy. Policy Sciences, 28, 127-148. Kennedy, K. & Lee, J. (2010). The changing role of Schools in Asian societies: Schools for the knowledge society (paperback version). New York/ London: Routledge, Kennedy. K. & OConnor, D. (1999). The role of elite policy makers in the construction of civics education in Australia: Methodological issues in sampling, identification and selection. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Australian Association for Research in Education, Melbourne, November 29, 1999. Lai, K. (2005), Sorting priorities for education reforms to avoid adding pressure on teachers, Hong Kong Economic Times. Law, F. (2004). The opening speech in the

Presentation Ceremony of Hang Lung Mathematic Scholarship. (In Chinese) Retrieved July 01, 2005, from http:// www.emb.gov.hk/index.aspx? langno=2&nodeid=134&uid=101355 Lee, J. (2009). Educational evaluation in Hong Kong: Status and challenges. In S.S. Peng and J.C.K. Lee (Eds.), Educational evaluation in East Asia: Emerging issues and challenges (pp.61 -71). New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Lee, J., Yin, H. & Zhou, X. (2008). Facilitating teacher professional development through 4-P Model: Experiences from Hong Kongs Partnership for Improvement of Learning and Teaching (PILT) Project. Journal of Educational Research and Development, 4(2), 17-48. Taiwan: Preparatory Office, National Academy for Educational Research. (In Chinese) Lee, J., Ding, D. & Song, H. (2008). School supervision and evaluation in China: The Shanghai perspective. Quality Assurance in Education, 16(2), 148163. Li, K. & Ngan, M. (2009). Learning to Teach with Information and Communication Technology in a Teacher Induction Program. International Journal of Technology in Teaching and Learning, 5(1), 4961. Madaus, G. (1988). The distortion of teaching and testing: High-stakes testing and instruction. peabody Journal of Education, 65(3), 29-46. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Morrissey, C. (1970). On oral history interviewing. In L. Dexter (Ed). Elite and Specialised Interviewing . Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 109-130 Newton, J. (2000). Feeding the Beast or Improving Quality?: Academics'

Asian Journal of Educational Research and Synergy 2(1) , May 2010

45

MING YAN NGAN, JOHN CHI-KIN LEE and GAVIN T. L. BROWN

perceptions of quality assurance and quality monitoring. Quality in Higher Education, 6(2), 153 163. UK: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. Ngan, M. & Lee, J. (2008). Multiple Perspectives Review: The Hong Kong Curriculum Reform since 1997. Hong Kong Teachers Centre Journal, 7, 118. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Teacher Centre. NVivo (Version 7). (2006). [Computer software]. Doncaster, Vic, Aus.: QSR International. Pang, N. (2000). Performance Indicators and Quality Assurance, Education Journal, 28(2), 137-155. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Institute of Educational Research and the Faculty of Education, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. (Article written in Chinese) Pang, N. (2005). Review on the Development of the Quality Assurance Framework for Hong Kong Schools, Education Journal, 33(1-2), 89-107. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Institute of Educational Research and the Faculty of Education, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. (Article written in Chinese) Patton, M. (1990). Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Peng, S. & Lee, J. (2009). Introduction. In S.S. Peng and J.C.K. Lee (Eds.), Educational evaluation in East Asia: Emerging issues and challenges (pp.122). New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Steinmetz, A. (2000). The discrepancy evaluation model. In D. L. Stuflebeam, G. F.Madus, & T. Kellaghan (Eds.), Evaluation models: Viewpoints on educational and human services evaluation (2nd ed.). Boston: Kluwer. Wu, S. & Tang, S. (2004). Experience on School-based Self-evaluation of

Primary School in Hong Kong, New Horizons in Education, 49, 57-61. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Teachers' Association. (Article written in Chinese) Wu, S. (2001). The development of the Hong Kong Quality Assurance and Scchoolbased Assessment. Paper presented in CESHK Annual Conference 2001, Hong Kong: HKIEd. (Article written in Chinese) Wu, S. (2002). The Development of Schoolbased Evaluation in Hong Kong. New Horizons in Education, 46, 33-37. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Teachers' Association. (Article written in Chinese)

Asian Journal of Educational Research and Synergy 2(1) , May 2010

46

You might also like

- School Climate2 0Document28 pagesSchool Climate2 0John TomsettNo ratings yet

- U.S. Principals Interpretation and Implementation of Teacher EvaDocument16 pagesU.S. Principals Interpretation and Implementation of Teacher EvaRaúl CartagenaNo ratings yet

- Ronnie BagoDocument43 pagesRonnie BagoChristian Paul ChuaNo ratings yet

- Wang Xu Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesWang Xu Literature ReviewIzyan HazwaniNo ratings yet

- Centre For Understanding Behaviour Change: What Influences Teachers To Change Their Practice? A Rapid Research ReviewDocument24 pagesCentre For Understanding Behaviour Change: What Influences Teachers To Change Their Practice? A Rapid Research ReviewlianNo ratings yet

- ED704&705 - Concept PaperDocument3 pagesED704&705 - Concept PaperANGELO UNAYNo ratings yet

- Teachers Perceptions On Factors Influence AdoptioDocument13 pagesTeachers Perceptions On Factors Influence AdoptioMarysia JasiorowskaNo ratings yet

- 2 Caldero DONEDocument13 pages2 Caldero DONEwiolliamkritsonisNo ratings yet

- Teacher-Student Relationships Impact Student SuccessDocument3 pagesTeacher-Student Relationships Impact Student Successana macatangayNo ratings yet

- The Effects of School-Based Management in The Philippines: Policy Research Working Paper 5248Document29 pagesThe Effects of School-Based Management in The Philippines: Policy Research Working Paper 5248Ced HernandezNo ratings yet

- Teacher's Beliefs About Educational QualityDocument38 pagesTeacher's Beliefs About Educational QualityFrancisco OlivosNo ratings yet

- 'School Administrators' and Stakeholders' Attitudes Toward, and Perspectives On, School Improvement PlanningDocument20 pages'School Administrators' and Stakeholders' Attitudes Toward, and Perspectives On, School Improvement PlanningBilal RazaNo ratings yet

- An Evaluation of The Effectiveness of Co-Curricular Policy in Developing TalentDocument5 pagesAn Evaluation of The Effectiveness of Co-Curricular Policy in Developing TalentAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Guidelines in Writing The ResearchDocument62 pagesGuidelines in Writing The ResearchKaren GayNo ratings yet

- Traditional Teaching Strategies Versus Cooperative Teaching Strategies: Which Can Improve Achievement Scores in Chinese Middle Schools?Document10 pagesTraditional Teaching Strategies Versus Cooperative Teaching Strategies: Which Can Improve Achievement Scores in Chinese Middle Schools?إسراء الصاويNo ratings yet

- Heafner 2017Document9 pagesHeafner 2017Jonalyn JumadilNo ratings yet

- EJ1244634Document15 pagesEJ1244634Yoel Agung budiartoNo ratings yet

- CORRELATES OF PERFORMANCEDocument10 pagesCORRELATES OF PERFORMANCEBelikat UsangNo ratings yet

- Abstract:: Key Words: Student Discipline and Behavior Dimension, Instructional Staff DimensionDocument30 pagesAbstract:: Key Words: Student Discipline and Behavior Dimension, Instructional Staff DimensionJudeza PuseNo ratings yet

- Literature Review-Standards Based GradingDocument17 pagesLiterature Review-Standards Based Gradingapi-286450231100% (1)

- EJ1111078Document9 pagesEJ1111078Crispearl Tapao BatacanduloNo ratings yet

- WP x'16 Helal and CoelliDocument47 pagesWP x'16 Helal and CoelliCraig Butt100% (1)

- RTL Assessment TwoDocument11 pagesRTL Assessment Twoapi-331867409No ratings yet

- International Journals Call For Paper HTTP://WWW - Iiste.org/journalsDocument5 pagesInternational Journals Call For Paper HTTP://WWW - Iiste.org/journalsAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Applied ResearchDocument24 pagesApplied ResearchJay Freey GaliciaNo ratings yet

- 11.. Principals' and Teachers' Perceptions On Factors Affecting Quality Education at The Selected Basic Education High Schools in SagaingDocument11 pages11.. Principals' and Teachers' Perceptions On Factors Affecting Quality Education at The Selected Basic Education High Schools in SagaingToe ToeNo ratings yet

- Stakeholders' Role in School Improvement PlansDocument28 pagesStakeholders' Role in School Improvement PlansReciept MakerNo ratings yet

- Assessment and EvaluationDocument38 pagesAssessment and EvaluationJefcy NievaNo ratings yet

- AhmadJohariSihes2015 PerceptionsPracticesandProblemsofSchool-BasedAssessmentDocument13 pagesAhmadJohariSihes2015 PerceptionsPracticesandProblemsofSchool-BasedAssessmentHema RamachandranNo ratings yet

- A Contextual Analysis of Factors Tend To Be Effective School System in TurkeyDocument5 pagesA Contextual Analysis of Factors Tend To Be Effective School System in TurkeyNIK SASLIZANo ratings yet

- Helping Students ImproveDocument8 pagesHelping Students Improvecyberprime_prasetyoNo ratings yet

- School Based Management and Learning Outcomes Experimental Evidence From Colima MexicoDocument29 pagesSchool Based Management and Learning Outcomes Experimental Evidence From Colima MexicoChristy AndamNo ratings yet

- Do Extracurricular Activities Matter? Chapter 1: IntroductionDocument18 pagesDo Extracurricular Activities Matter? Chapter 1: IntroductionJason Wong100% (1)

- Webb, Brigman, and Campbell 05Document8 pagesWebb, Brigman, and Campbell 05Veronica ChiriacNo ratings yet

- Teacher Motivation and Students Academic Performance in Obio Akpor Mary Agorondu Project Work 1-5 ChaptersDocument69 pagesTeacher Motivation and Students Academic Performance in Obio Akpor Mary Agorondu Project Work 1-5 ChaptersEmmanuel prince NoryaaNo ratings yet

- Successful Leadership Practices of Head Teachers For School ImprovementDocument19 pagesSuccessful Leadership Practices of Head Teachers For School ImprovementAmbreen ZainebNo ratings yet

- Acknowledgement: Funding For This Study Was Provided by The Measuring Teachers'Document8 pagesAcknowledgement: Funding For This Study Was Provided by The Measuring Teachers'Prihan AgusNo ratings yet

- Teacher Evaluation FinalDocument27 pagesTeacher Evaluation Finalapi-310209692No ratings yet

- MBEH'S - Final - Work (1) 27Document72 pagesMBEH'S - Final - Work (1) 27Fon Palverd Brent BridenNo ratings yet

- TT279Document26 pagesTT279Fred MillerNo ratings yet

- Student Perspectives of Assessment ConsiDocument30 pagesStudent Perspectives of Assessment ConsiXhiemay ErenoNo ratings yet

- Marketing Research PROJECTDocument26 pagesMarketing Research PROJECTmanojbenNo ratings yet

- Research Paper FinalDocument22 pagesResearch Paper Finalapi-532610952100% (1)

- The Effects of Formative Assessment On Academic Achievement, Attitudes Toward The Lesson, and Self-Regulation SkillsDocument34 pagesThe Effects of Formative Assessment On Academic Achievement, Attitudes Toward The Lesson, and Self-Regulation SkillsgulNo ratings yet

- Concept PaperDocument7 pagesConcept PaperJoseph EneroNo ratings yet

- Muhammad Faizal A. Ghani Et Al (2011) - SE in Excellent Schools in Msia & BruneiDocument8 pagesMuhammad Faizal A. Ghani Et Al (2011) - SE in Excellent Schools in Msia & BruneiAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Module 6 Research PaperDocument14 pagesModule 6 Research PaperJNo ratings yet

- Supervisory RolesDocument8 pagesSupervisory RolesDeborah BandahalaNo ratings yet

- Contoh Jurnal Internasional Teflin-UmDocument15 pagesContoh Jurnal Internasional Teflin-UmKarim KurdiNo ratings yet

- Exploring the Supervoisory Needs of School Heads and Teachers in West Simunul District-1Document7 pagesExploring the Supervoisory Needs of School Heads and Teachers in West Simunul District-1Mohammad Rajih BihNo ratings yet

- Critical Article Review 2Document8 pagesCritical Article Review 2Aimi Dayana JaafarNo ratings yet

- Teachers Approaches To Classroom Assessment A Large Scale Survey PDFDocument22 pagesTeachers Approaches To Classroom Assessment A Large Scale Survey PDFhillbloomsNo ratings yet

- Ej 1233111Document12 pagesEj 1233111Josias PerezNo ratings yet

- 08+IMJRISE+-+Assessing+the+Impact+of+Principal's+Instructional+Leadership,+School+Level,+and+Effectiveness+in+Educational+Institutions (1)Document10 pages08+IMJRISE+-+Assessing+the+Impact+of+Principal's+Instructional+Leadership,+School+Level,+and+Effectiveness+in+Educational+Institutions (1)Christian LazcanoNo ratings yet

- R8 PDFDocument14 pagesR8 PDF20040279 Nguyễn Thị Hoàng DiệpNo ratings yet

- GROUP 4 MASEIS 4 Evaluation Study ProposalDocument19 pagesGROUP 4 MASEIS 4 Evaluation Study ProposalJENNY VERZOSANo ratings yet

- Examination of School-Based Management in IndonesiaDocument31 pagesExamination of School-Based Management in IndonesiaHafizah PakahNo ratings yet

- School (Self) Evaluation and Student AchievementDocument21 pagesSchool (Self) Evaluation and Student AchievementSorayuth RitticharoonrotNo ratings yet

- Effects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsFrom EverandEffects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsNo ratings yet

- Teachers’ Perceptions of Their Literacy Professional DevelopmentFrom EverandTeachers’ Perceptions of Their Literacy Professional DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Language TestingDocument3 pagesLanguage Testingmay monNo ratings yet

- Ielts Writing Task 2Document17 pagesIelts Writing Task 2may monNo ratings yet

- British Edu Influence Myanmar EduDocument204 pagesBritish Edu Influence Myanmar Edumay monNo ratings yet

- Ielts Mock TestDocument8 pagesIelts Mock Testmay monNo ratings yet

- IELTS Speaking Sample QuestionsDocument969 pagesIELTS Speaking Sample Questionsmay mon0% (1)

- Grammar Translation MethodDocument3 pagesGrammar Translation Methodmay monNo ratings yet

- French Man Lands Job with Billboard CVDocument4 pagesFrench Man Lands Job with Billboard CVMay Phoo MonNo ratings yet

- Bloom TaxonomyDocument2 pagesBloom Taxonomymay monNo ratings yet

- Argumentative Essasys TitlesDocument2 pagesArgumentative Essasys Titlesmay monNo ratings yet

- Ielts Essays TitleDocument4 pagesIelts Essays Titlemay monNo ratings yet

- Ielts Speaking ExercisesDocument21 pagesIelts Speaking Exercisesmay monNo ratings yet

- IELTS Speaking Topic 100Document61 pagesIELTS Speaking Topic 100wakeeye100% (4)

- IELTS Test in India and The UKDocument9 pagesIELTS Test in India and The UKMay Phoo MonNo ratings yet

- IELTS Speaking Part 3Document31 pagesIELTS Speaking Part 3may mon0% (2)

- Ielts Speaking ExercisesDocument21 pagesIelts Speaking Exercisesmay monNo ratings yet

- QuizDocument3 pagesQuizmalikbilalhussainNo ratings yet

- Academic Test 1 Question PaperDocument21 pagesAcademic Test 1 Question PaperPeach Peach Lynn0% (2)

- IELTS Test in Russia and Saudi ArabiaDocument4 pagesIELTS Test in Russia and Saudi Arabiamay monNo ratings yet

- Describing CharacterDocument5 pagesDescribing CharacterDick B.No ratings yet

- IELTS Speaking Test 1Document16 pagesIELTS Speaking Test 1may monNo ratings yet

- Ko PeterDocument242 pagesKo Petermay monNo ratings yet

- Marking scheme and topics for CBSE Class 12 English Core board examDocument17 pagesMarking scheme and topics for CBSE Class 12 English Core board examRonaldNo ratings yet

- Pemdas Poster RubricDocument1 pagePemdas Poster Rubricapi-366582437No ratings yet

- Aitsl Learning Intentions and Success Criteria Strategy PDFDocument1 pageAitsl Learning Intentions and Success Criteria Strategy PDFBen RobertsNo ratings yet

- Politics-IR UK 2014 WebDocument36 pagesPolitics-IR UK 2014 Webnthu55660% (1)

- TTL 2 SS Lesson 8Document29 pagesTTL 2 SS Lesson 8Hanie QsqnNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Reading Comprehension DifficultiesDocument9 pagesThesis On Reading Comprehension DifficultiesSarah Pollard100% (2)

- Mentors ListDocument5 pagesMentors ListAhnaf HamidNo ratings yet

- Social Studies Major - Set B - Part 3Document3 pagesSocial Studies Major - Set B - Part 3Jane Uranza CadagueNo ratings yet

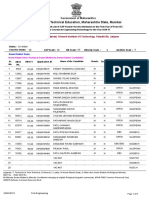

- Directorate of Technical Education, Maharashtra State, MumbaiDocument45 pagesDirectorate of Technical Education, Maharashtra State, Mumbaisanjayrsugandhi75No ratings yet

- Justice Thesis StatementsDocument5 pagesJustice Thesis StatementsLisa Garcia100% (2)

- Story ElementsDocument3 pagesStory ElementsnrblackmanNo ratings yet

- (Mathematics Education Library) Efraim Fischbein-Intuition in Science and Mathematics - An Educational Approach-D. Riedel (1987)Document17 pages(Mathematics Education Library) Efraim Fischbein-Intuition in Science and Mathematics - An Educational Approach-D. Riedel (1987)Nenden Mutiara SariNo ratings yet

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Regression AnalysisDocument9 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of Regression AnalysisAPOORVA PANDEYNo ratings yet

- Teaching English Through Songs and GamesDocument7 pagesTeaching English Through Songs and GamesOrastean Andreea Simona100% (1)

- ACT 201306 FormDocument52 pagesACT 201306 FormJJNo ratings yet

- Writing A DBA DissertationDocument5 pagesWriting A DBA DissertationHelpWritingAPaperForCollegeCanada100% (1)

- Kearns Vairani 1994 Introduction To Computational Learning Thoery Ch01Document41 pagesKearns Vairani 1994 Introduction To Computational Learning Thoery Ch01klaus peterNo ratings yet

- Family Health NursingDocument6 pagesFamily Health NursingDanna Bornilla RodriguezNo ratings yet

- I. Objectives: Mga Isyung Pangkapaligiran at Pang-EkonomiyaDocument4 pagesI. Objectives: Mga Isyung Pangkapaligiran at Pang-EkonomiyaDIANNE BORDANNo ratings yet

- Effective Leadership Strategies for Church SustainabilityDocument20 pagesEffective Leadership Strategies for Church SustainabilityUMI Pascal100% (1)

- Ui V Bonifacio DigestDocument2 pagesUi V Bonifacio DigestPamela Claudio100% (2)

- RPH PDPR 2-4 OgosDocument2 pagesRPH PDPR 2-4 OgosLAILI ATIQAH BINTI JIHAT MoeNo ratings yet

- ISTQB ATA (Advanced Test Analyst) Certification Exam Practice Questions For Testing ProcessDocument10 pagesISTQB ATA (Advanced Test Analyst) Certification Exam Practice Questions For Testing ProcessShanthi Kumar Vemulapalli100% (1)

- PT3 Listening Sample Test - Key PDFDocument2 pagesPT3 Listening Sample Test - Key PDFElaine ChiamNo ratings yet

- Ewc661 Draft ProposalDocument5 pagesEwc661 Draft ProposalAzreen IzzatyNo ratings yet

- Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research ChandigarhDocument45 pagesPostgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research ChandigarhDMnDLNo ratings yet

- Sarala Homeopathic HospitalDocument2 pagesSarala Homeopathic HospitalSmvs Byrakur KolarNo ratings yet

- Willingness To Communicate: Crossing The Psychological Rubicon From Learning To CommunicationDocument38 pagesWillingness To Communicate: Crossing The Psychological Rubicon From Learning To Communicationt3nee702No ratings yet

- MSC Projectmanagement 2022Document2 pagesMSC Projectmanagement 2022Hein HtetNo ratings yet

- Easyclass - Create Your Digital Classroom For Free...Document9 pagesEasyclass - Create Your Digital Classroom For Free...mohamad1010No ratings yet