Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dendrochronolgy: Knowledge and Understanding

Uploaded by

JDMcDougallOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dendrochronolgy: Knowledge and Understanding

Uploaded by

JDMcDougallCopyright:

Available Formats

Dendrochronolgy

Knowledge and understanding Suitability of dating techniques Case studies of application of dating techniques Skills: Presentation of dating evidence in archaeological reports Interpreting the conventions used in dating diagrams and tables.

Dendrochronology is the formal term for tree-ring dating, the archaeological dating method that uses the growth rings of long-lived trees as a calendar. Tree-ring dating was one of the first absolute dating methods. It works by comparing tree ring samples found on site with a pre-established sequence of tree rings for the period in question. In general, during the lifetimes of trees, each year the tree grows is marked by a growth ring; the tree gains a little bit of girth each year. The width of the ring added to the outside of the tree is in part dependent on the amount of moisture available to the tree--thus trees in the same area add thin rings during dry years and thick rings during wet years. If a research can obtain a string of tree samples that overlap, a precise sequence of tree rings can be derived. Dendrochronology is extremely precise, allowing archaeologists to name the specific year a tree was cut to make a wooden object.

But, in addition, the use of dendrochronolgy as a backup method to radiocarbon dating allowed scientists to recognize the regular pattern in which atmospheric conditions caused radiocarbon dates to vary. Radiocarbon dates which have been corrected-or rather, calibrated-by comparison to dendrochronological records are designated by the abbreviation cal BP, or calibrated years before the present. Over the past hundred years or so, tree ring sequences have been built all over the world, with the longest to date consisting of a 10,000 year sequence in central Europe completed on oak trees by the Hohenheim Laboratory. Case Study-The Sweet Track, Somerset See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sweet_Track

The Sweet Track (named after the man who discovered it) is the oldest prehistoric trackway or causeway found in Britain. It was constructed nearly 6000 years ago by early farmers in Somerset. The workmanship is remarkably sophisticated: woods of different qualities were chosen to make a sturdy footway over the marshy lands, known today as the 'Somerset Levels'. The Sweet Track was built in either 3807 or 3806 BC and was the oldest timber trackway discovered in Northern Europe until the 2009 discovery of a 6,000-year-old trackway in Plumstead, London. It is now known that the Sweet Track was predominantly built over the course of an earlier structure, the Post Track. Recent advances in the dating of wood by the study of tree-rings (dendrochronology) have enabled the construction to be placed in the years 3807/3806 BC. The track extended across the now largely drained marsh between what was then an island at Westhay and a ridge of high ground at Shapwick, a distance close to 2,000 metres. The track is one of a network that once crossed the Somerset Levels. Various artefacts, including a jadeitite ceremonial axe head, have been found along its length.

Cross section of construction

Preparation and construction According to pollen evidence, the whole of Britain would have been covered in forests at this time. The Neolithic peoples would have burnt and cleared the forests to have the land on which to grow their crops, mostly grains. A fair degree of organization is evident in the stockpiling of wood and construction of the tracks, and some members of the community would have had to have skills in woodworking. Using stone and flint axes, the trees for the track were cut on dry land with different cutting techniques used, depending on their age. Older oaks were cut vertically whilst younger trees tangentially. Modern research has been

carried out using replica axes and the cut marks have also been studied to establish the methods of cutting used. The planks of wood were put together in the marsh, the final construction taking about a day to complete. Long poles were driven slantwise into the ground and then planks were laid in between, held in place by vertical pegs. The planks were made of oak, ash and lime. The poles and pegs were made mainly of hazel and alder. There are also remains of another track, known as the Post Track, which dates 30 years earlier than the Sweet Track, 3838 BCE. It ran roughly parallel to the Sweet Track, possibly used by the builders of the Sweet Track as an access route. Materials The track is made of three basic components: planks made of oak, ash and lime, and rails and pegs made mainly of hazel and alder. The separate components were prepared on dry land and brought into the wet area. Long poles were laid end to end and secured by sharpened pegs driven slantwise into the ground on either side. The planks were then wedged into place between the peg-tops, parallel to the rails beneath, and held firmly in position by vertical pegs. The whole track, two kilometres in length, could have been assembled in a single day from the pre-shaped units. The track was only used for a period of around 10 years and was then abandoned, probably due to rising water levels. Following its discovery in 1970, most of the track has been left in its original location, with active conservation measures taken, including a water pumping and distribution system to maintain the wood in its damp condition. Some of the track is stored at the British Museum and a reconstruction of a section was built at the Peat Moors Centre near Glastonbury. Analysis of the Sweet Track's timbers has aided research into Neolithic Era dendrochronolgy; comparisons with wood from the River Trent enabled a fuller mapping of the rings, and their relationship with the climate of the period. The wood used to build the track is now classed as bog-wood, the name given to wood (of any source) that for long periods (sometimes hundreds of thousands of years) has been buried in peat bogs, and kept from decaying by the acidic and anaerobic bog conditions. Bog-wood is usually stained brown by tannins dissolved in the acidic water, and represents an early stage of fossilisation In 1973 a jadeitite axe head was found alongside the track; it is thought to have been placed there as an offering. [One of over 100 similar axe heads found in Britain and Ireland, its good condition and its precious material suggest that it was a symbolic axe, rather than one used to cut wood.[] Because of the difficulty of working this material, which was derived from the Alpine area of Europe, all the axe heads of this type found in Great Britain are thought to have been non-utilitarian and to have represented some form of currency or be the products of gift exchange. Radiocarbon dating of the peat in which the axe head was discovered suggests that it was deposited in about 3200 BC. Wooden artefacts found at the site include paddles, a dish, arrow shafts, parts of four hazel bows, an axe, yew pins, digging sticks, a comb, mattock, toggles and a spoon fragment. Finds made from other materials, such as flint flakes, arrowheads and a chipped flint axe (in mint condition) have also been made.[21]

A geophysical survey of the area in 2008 showed unclear magnetometer data; the wood may be influencing the peat's hydrology, causing the loss or collection of minerals within the pore water and peat matrix. In the past it has been suggested that peat deposits are too wet, too deep, too homogenous or similar to the target for traditional dry land geophysical techniques to be of any use. However, recent research demonstrates, there are detectable physical and chemical differences between the archaeological deposits and structures and the surrounding matrix. The surveys over a preserved section of the track at Shapwick all located an anomaly in the known location of the trackway. The resistivity and conductivity (EM) surveys showed a linear anomaly running north/south, 2m wide and 16m in from the western edge of the grid. They also show a gradient of increasing resistivity values from west to east across the grid. The magnetic survey showed an area of enhancement in the far south east corner of the survey and a faint linear negative anomaly about 1m wide running north-south about 14m in from the western grid edge. The GPR showed a large dendritic reflector in the south west quadrant of the grid between 10-28ns/ 0.4m deep. There is a faint linear reflector at roughly the same depth running north/south, 2m wide and about 16m in from the western grid edge. From this depth the northern edge of the grid and in particular the north-east corner shows high amplitude responses that seem to be cut at the 16m mark, in line with the previously noted anomaly. The linear north/south anomaly is interpreted as being, or being caused by the Sweet Track. The stronger dendritic anomaly in the GPR data is interpreted as being a bog oak. Trackway or Ritual Path? Discussing the discarded items, such as jadeite polished axe, pottery sherds, flint flakes, a core and a chipped flint axe Archaeologist Dr Clive Bond argues that rather than a means of travelling from A to B, this structure and landscape setting provides a glimpse into the origins of the earliest Neolithic beliefs in South-West England. The track was anchored to a particular landscape setting, the sand island at Shapwick. This was a socially constructed place, revisited over generations, drawing on a Mesolithic hunter-gatherer biography. Therefore, understanding this structure and what it meant to those who built it is pivotal to understanding the Neolithic worldview. Conservation Although the wood recovered from the levels was visually intact it was extremely degraded and very soft. Where possible, pieces of wood in good condition, or the worked ends of pegs, were taken away and conserved for later analysis. The conservation process involved keeping the wood in heated tanks in a solution of polyethylene glycol and, by a process of evaporation, gradually replacing the water in the wood with the wax over a period of about nine months. After this treatment the wood was removed from the tank and wiped clean. As the wax cooled and hardened the artifact became firm and could be handled freely.

Click here for notes on Flag Fen, which has some similarities to Sweet Track

You might also like

- Renfrew 2020 Archaeology-Páginas-48-74-Páginas-17,20,23,26-27Document5 pagesRenfrew 2020 Archaeology-Páginas-48-74-Páginas-17,20,23,26-27GIANCARLOS CASTILLO FLORESNo ratings yet

- Prehistoric Architecture and Early CivilizationsDocument368 pagesPrehistoric Architecture and Early CivilizationsNishant RajputNo ratings yet

- Lincoln University and ST CathsDocument4 pagesLincoln University and ST CathssolsecretaryNo ratings yet

- Old European Culture - Togher, Tocher - Wooden TrackwaysDocument17 pagesOld European Culture - Togher, Tocher - Wooden TrackwaysDusan_LarssonNo ratings yet

- Stonehenge Notes and TheoriesDocument7 pagesStonehenge Notes and TheoriesLily Evans0% (2)

- Stones of StennessDocument3 pagesStones of Stennesscorinne millsNo ratings yet

- Reviews: Prehistoric Coastal Communities: The Mesolithic in Western BritainDocument40 pagesReviews: Prehistoric Coastal Communities: The Mesolithic in Western BritainIsolda Alanna RlNo ratings yet

- Scotland RocksDocument4 pagesScotland RocksThe Royal Society of EdinburghNo ratings yet

- Seahenge: a quest for life and death in Bronze Age BritainFrom EverandSeahenge: a quest for life and death in Bronze Age BritainRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (19)

- Ni-Vanuatu Lapita PotteryDocument11 pagesNi-Vanuatu Lapita PotteryqjswanNo ratings yet

- Napi Angol Percek Augusztus 3Document5 pagesNapi Angol Percek Augusztus 3Zsuzsa SzékelyNo ratings yet

- Ancients TimelineDocument2 pagesAncients Timelinehadu48No ratings yet

- Tree-Rings, Kings and Old World Archaeology and Environment: Papers Presented in Honor of Peter Ian KuniholmFrom EverandTree-Rings, Kings and Old World Archaeology and Environment: Papers Presented in Honor of Peter Ian KuniholmNo ratings yet

- Occasional Caves and Temporary TentsDocument3 pagesOccasional Caves and Temporary TentsJames AsasNo ratings yet

- The Cambridge Anthropological Expedition To Torres Straits and S 1899Document6 pagesThe Cambridge Anthropological Expedition To Torres Straits and S 1899MUPyP comunidadNo ratings yet

- CBA-SW Journal No.22 - Excavations at Boden Vean, Manaccan, Cornwall, 2008 - James Gossip.Document4 pagesCBA-SW Journal No.22 - Excavations at Boden Vean, Manaccan, Cornwall, 2008 - James Gossip.CBASWNo ratings yet

- Our Fragile HeritageDocument12 pagesOur Fragile HeritageChromaticghost2No ratings yet

- A Study of Some Californian Indian Rock Art Pigments David A. Scott and William D. HyderDocument20 pagesA Study of Some Californian Indian Rock Art Pigments David A. Scott and William D. HyderAldo WatanaveNo ratings yet

- 1998 UMAU Mellor ReportDocument12 pages1998 UMAU Mellor ReportdigitalpastNo ratings yet

- GLC-01 Handout (Origins)Document11 pagesGLC-01 Handout (Origins)JanisNo ratings yet

- British Culture and CivilizationDocument218 pagesBritish Culture and Civilizationhereg daniela100% (3)

- Aditya Singh 2016130 Sofo 1st Year Assignment2Document8 pagesAditya Singh 2016130 Sofo 1st Year Assignment2Aditya SinghNo ratings yet

- Geography Hengistbury Head CourseworkDocument4 pagesGeography Hengistbury Head Courseworkbcrbcw6a100% (2)

- Walpole Landfill Site, Pawlett, Somerset The Archaeology: Project UpdateDocument5 pagesWalpole Landfill Site, Pawlett, Somerset The Archaeology: Project UpdateC & N HollinrakeNo ratings yet

- CAM 16 Test 04Document11 pagesCAM 16 Test 04Trương Khiết AnhNo ratings yet

- Mesolithic Bows From Denmark and NortherDocument8 pagesMesolithic Bows From Denmark and NortherCharles CarsonNo ratings yet

- 01 - Prehistoric PeriodDocument24 pages01 - Prehistoric PeriodPrachi Rai Khanal100% (1)

- Hengistbury Head Geography CourseworkDocument8 pagesHengistbury Head Geography Courseworkbcr1xd5a100% (2)

- Ring of BrodgarDocument5 pagesRing of Brodgarcorinne millsNo ratings yet

- GeonewsDocument4 pagesGeonewsapi-299813057No ratings yet

- SCCHC 2012 Pluckemin RPT 2 Surface CollectionDocument44 pagesSCCHC 2012 Pluckemin RPT 2 Surface Collectionjvanderveerhouse100% (1)

- Paluxy River Footprints RevisitedDocument22 pagesPaluxy River Footprints RevisitedtehsmaNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Earliest Settlements 1. The PaleolithicDocument12 pagesUnit 1 Earliest Settlements 1. The PaleolithicPablo Fernández-AriasNo ratings yet

- Stonehenge Research Paper ConclusionDocument9 pagesStonehenge Research Paper Conclusiontug0l0byh1g2100% (1)

- Ancient Woodland: History, Industry and CraftsFrom EverandAncient Woodland: History, Industry and CraftsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Prehistoric PeriodDocument4 pagesPrehistoric PeriodTihago Girbau100% (1)

- Ancient Solar Storm Pinpoints Viking Settlement in Americas Exactly 1000 Years AgoDocument5 pagesAncient Solar Storm Pinpoints Viking Settlement in Americas Exactly 1000 Years AgoJorge Vivas SantistebanNo ratings yet

- Some Recent Danish Experiments in Neolithic AgricultureDocument8 pagesSome Recent Danish Experiments in Neolithic AgricultureRob FurnaldNo ratings yet

- 1999 AA AustralianExcavationsAtMarkiDocument4 pages1999 AA AustralianExcavationsAtMarkiGeorge DemetriosNo ratings yet

- Rock Articles 10Document18 pagesRock Articles 10Kate SharpeNo ratings yet

- A Lake Dwelling in its Landscape: Iron Age settlement at Cults Loch, Castle Kennedy, Dumfries & GallowayFrom EverandA Lake Dwelling in its Landscape: Iron Age settlement at Cults Loch, Castle Kennedy, Dumfries & GallowayNo ratings yet

- Dating Techniques: How Old Is ItDocument67 pagesDating Techniques: How Old Is ItCatriona SpillaneNo ratings yet

- Summary of Michael Parker Pearson's Stonehenge - A New UnderstandingFrom EverandSummary of Michael Parker Pearson's Stonehenge - A New UnderstandingNo ratings yet

- Tools Available For Cultivation in Prehistoric Britain Davam 1Document4 pagesTools Available For Cultivation in Prehistoric Britain Davam 1alo62No ratings yet

- The Use and reuse of stone circles: Fieldwork at five Scottish monuments and its implicationsFrom EverandThe Use and reuse of stone circles: Fieldwork at five Scottish monuments and its implicationsNo ratings yet

- The Ellesmere EmbarrassmentsDocument23 pagesThe Ellesmere Embarrassmentsrkomar333No ratings yet

- Building StonehengeDocument7 pagesBuilding StonehengeShradha AroraNo ratings yet

- History of Ancient Civilization by Charles SeignobosDocument249 pagesHistory of Ancient Civilization by Charles SeignobosLuis RuizNo ratings yet

- Dinosaur Trackway SiteoxfordDocument30 pagesDinosaur Trackway SiteoxfordnomadNo ratings yet

- Prehistoric ArchitectureDocument5 pagesPrehistoric ArchitectureDino Amiel Bancaso Bongcayao0% (1)

- Prehistoric ArchitectureDocument5 pagesPrehistoric ArchitectureDino Amiel Bancaso Bongcayao100% (2)

- Ancient History Formative Exam - Cheat SheetDocument4 pagesAncient History Formative Exam - Cheat SheetSolar Bee MweeNo ratings yet

- Wind PowerDocument4 pagesWind PowerJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- As Archaeology SpecificationDocument8 pagesAs Archaeology SpecificationJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- The Educators-Summary of Radio 4 Series: Sir Ken Robinson-Schools Are A Barrier To Creativity, As He Has Argued OnDocument5 pagesThe Educators-Summary of Radio 4 Series: Sir Ken Robinson-Schools Are A Barrier To Creativity, As He Has Argued OnJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- Environmental Archaeology 2ndDocument49 pagesEnvironmental Archaeology 2ndDjumboDjett100% (1)

- Physical PpqsDocument4 pagesPhysical PpqsJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- Hurricane MitchOKrimDocument2 pagesHurricane MitchOKrimJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- Physical PpqsDocument4 pagesPhysical PpqsJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- Archaeological MethodsDocument64 pagesArchaeological MethodsJDMcDougall100% (3)

- The FarmerDocument2 pagesThe FarmerJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- Hurricane Mitch Strikes The CaribbeanDocument2 pagesHurricane Mitch Strikes The CaribbeanJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- National ParksDocument1 pageNational ParksJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- British Isles ScriptDocument5 pagesBritish Isles ScriptJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- MississippiDocument3 pagesMississippiJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- Hurricane MitchDeclanDocument2 pagesHurricane MitchDeclanJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- Hurricane Mitch Defeats Countries of Central AmericaDocument2 pagesHurricane Mitch Defeats Countries of Central AmericaJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- The Yellow RiverDocument2 pagesThe Yellow RiverJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- Hurricane MitchJaiDocument2 pagesHurricane MitchJaiJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- Dillon Geography Hurricane MitchDocument1 pageDillon Geography Hurricane MitchJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- Hurricane Mitch2Document2 pagesHurricane Mitch2JDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- Hurricane MitchDocument1 pageHurricane MitchJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- Geography River VolgaDocument3 pagesGeography River VolgaJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- Sample Answer For Ink ExerciseDocument1 pageSample Answer For Ink ExerciseJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- SectionsDocument2 pagesSectionsJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- Colorado RiverDocument2 pagesColorado RiverJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- River IndusDocument2 pagesRiver IndusJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- GlaciationDocument2 pagesGlaciationJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- Glaciation and Loch LomondDocument2 pagesGlaciation and Loch LomondJDMcDougall100% (1)

- Corries, Aretes and Pyramidal PeaksDocument4 pagesCorries, Aretes and Pyramidal PeaksJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

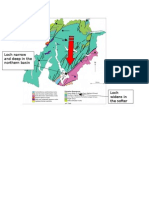

- Loch Lomond Geology MapDocument1 pageLoch Lomond Geology MapJDMcDougallNo ratings yet

- Req For Air InstallationDocument1 pageReq For Air InstallationArnold Ian Palen IINo ratings yet

- Phy 4023 Internal SyllabusDocument3 pagesPhy 4023 Internal SyllabuskasidoctorNo ratings yet

- Financial Maths Test 2020Document6 pagesFinancial Maths Test 2020Liem HuynhNo ratings yet

- Uses of Animation in MultimediaDocument14 pagesUses of Animation in MultimedianujhdfrkNo ratings yet

- Georg Lukács Selected Correspondence 1902 1920 Dialogues With Weber Simmel Buber Mannheim and OthersDocument320 pagesGeorg Lukács Selected Correspondence 1902 1920 Dialogues With Weber Simmel Buber Mannheim and OthersSofia Barelli100% (1)

- Pressure Drop CalcDocument24 pagesPressure Drop CalcKorcan ÜnalNo ratings yet

- Math5 Q3 LAS Wk3Document7 pagesMath5 Q3 LAS Wk3Chikay Ko UiNo ratings yet

- NEC SL1000 Hybrid PABX System Brochure PDFDocument2 pagesNEC SL1000 Hybrid PABX System Brochure PDFpslimps100% (1)

- FAQ OBD-SuzukiDocument3 pagesFAQ OBD-SuzukisakisNo ratings yet

- Borges - The South & The Lottery of BabylonDocument5 pagesBorges - The South & The Lottery of Babylonleprachaunpix100% (1)

- GD-ÑT Thaønh phoá Hoà Chí Minh Tröôøng THPT Bình Phuù - Quaän 6 Ñeà Thi Thöø Thí Kỳ Thi Tốt Nghiệp THPT Quốc GiaDocument4 pagesGD-ÑT Thaønh phoá Hoà Chí Minh Tröôøng THPT Bình Phuù - Quaän 6 Ñeà Thi Thöø Thí Kỳ Thi Tốt Nghiệp THPT Quốc GiaNgọc TrầnNo ratings yet

- Mona LisaDocument7 pagesMona LisaTrupa De Teatru MagneNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts of IHLDocument8 pagesBasic Concepts of IHLFrancisJosefTomotorgoGoingo100% (1)

- Uponor Push 23b Shunt Med Wilo Pumpe MANDocument20 pagesUponor Push 23b Shunt Med Wilo Pumpe MANschritte1No ratings yet

- Summary of Islamic CivilizationDocument2 pagesSummary of Islamic CivilizationKhairulAkmalNo ratings yet

- 2013 CFD BAlonsoTorres ChimiaDocument5 pages2013 CFD BAlonsoTorres ChimiaElvio JuniorNo ratings yet

- Application Letter SkillsDocument4 pagesApplication Letter SkillsAli Ma'sumNo ratings yet

- DJJ 40173 Compile Notes - Final E-BookDocument195 pagesDJJ 40173 Compile Notes - Final E-BookNbilZariefNo ratings yet

- HydPumpDocument8 pagesHydPumpmanishhydraulic100% (1)

- Assignment Corrosion RustingDocument5 pagesAssignment Corrosion RustingADEBISI JELEEL ADEKUNLE100% (1)

- b700 Boysen Clear Acrylic EmulsionDocument6 pagesb700 Boysen Clear Acrylic Emulsionraighnejames19No ratings yet

- Book Review On Nadia Hasimi A House Without Windows For RC at Cu2022Document4 pagesBook Review On Nadia Hasimi A House Without Windows For RC at Cu2022Soma RoyNo ratings yet

- CNF ReviewerDocument3 pagesCNF ReviewerRichard R. GemotaNo ratings yet

- Important Text Book Based QuestionsDocument52 pagesImportant Text Book Based QuestionsSonamm YangkiiNo ratings yet

- Soal Latihan US Bahasa InggrisDocument5 pagesSoal Latihan US Bahasa Inggrispikri18120No ratings yet

- Rse 2.3Document16 pagesRse 2.3Rudra Sai SandeepNo ratings yet

- 794 Ac m04 Steersys enDocument31 pages794 Ac m04 Steersys enDavidCPNo ratings yet

- F.O.E ProjectDocument8 pagesF.O.E ProjectHarsh GandhiNo ratings yet

- Intermittent fasting is the right way to lose weightDocument5 pagesIntermittent fasting is the right way to lose weightMUHAMMAD NABIL BIN MOHD NAZRI MoeNo ratings yet

- AURAL COMPREHENSION INSTRUCTION: Principles and Practices: Remedial Instruction in EnglishDocument10 pagesAURAL COMPREHENSION INSTRUCTION: Principles and Practices: Remedial Instruction in EnglishVandolph Acupido CorpuzNo ratings yet