Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Anil-The Effect of Word of Mouth Communication On Academicianspurchasing Decision and The Factors Related To Word of PDF

Uploaded by

danikapanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Anil-The Effect of Word of Mouth Communication On Academicianspurchasing Decision and The Factors Related To Word of PDF

Uploaded by

danikapanCopyright:

Available Formats

THE EFFECT OF WORD OF MOUTH COMMUNICATION ON ACADEMICIANS PURCHASING DECISION AND THE FACTORS RELATED TO WORD OF MOUTH: A SAMPLE

OF KIRKLARELI UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT Assist. Prof. Dr. Nihat Kamil ANIL Kirklareli University/Vize Vocational School Vize MYO Vize / Kirklareli-TURKIYE Phone: +90-288-318-3444 E-mail: nihatanil@yahoo.com Assist. Prof. Dr. Kamil MALKOLU Kirklareli University / Institute of Social Sciences Kirklareli University Institute of Social Sciences Kirklareli-TURKIYE Phone: +90-288-212-9687 E-mail: kamilmalkoclu@hotmail.com Instr. Aye ANIL Kirklareli University/Vize Vocational School Vize MYO Vize / Kirklareli-TURKIYE Phone: +90-288-318-3444 E-mail: bayrakayse@yahoo.com Key words: Word-of-mouth, Kirklareli University, WOM among academicians Consumers are affected by several informational sources in todays globalized environment such as word of mouth (WOM) communication. WOM can be defined as the act of consumers providing positive or negative information to other consumers. The marketing literature abounds with the claim that WOM communication has a substantial influence on consumer purchase decisions. Especially, increased importance of consumer satisfaction makes WOM communication one of the key factors in purchasing decision. Like repeat purchases, the spread of WOM is largely driven by the customer's satisfaction with the product (Anderson 1998) and hence WOM (whether positive or negative) can be seen as an integral part of the value that the firm should associate with its customers (Hogan et al., 2004). For this reason, it should be important to determine the factors related to WOM communication not only for researchers but also especially for the practitioners. The aim of this study is to determine the effect of word of mouth communication on academicians purchasing decisions and the factors related to word of mouth. In this sense it has examined the effect of senders and receivers expertise about the product, tie strength between sender and receiver, the receivers perceived risk on the influence of word of mouth. In the study, survey method has been employed. A structured questionnaire has been addressed to full-time academicians at Kirklareli University. Correlation and ANOVA have been used to analyze data by SPSS. JEL Classification: M31, M39

1. INTRODUCTION Word of Mouth (WOM) is thousands of times more powerful than conventional marketing [.] because it is the most powerful way to make the decision easier and accelerate your prospects decision process. As stated above by Silverman (2001: 21-22) the marketing literature has many claims that WOM communication has a substantial influence on consumer purchase decision. Increased importance of consumer satisfaction makes WOM communication one of the key factors. Therefore, it should be important to determine the factors related to WOM communication. In this sense, the definition, the importance of WOM, and its types have been given in the first section. The next section examines elements of WOM such as the effect of senders and receivers expertise about the product, tie strength between sender and receiver, the receivers perceived risks on the influence of WOM. The third section is the empirical research on academicians at Kirklareli University. The study ends with the conclusion and limitations and further research section. 1.1. The Meaning of Word of Mouth The term word-of-mouth (WOM) was originally coined by William H. Whyte, Jr. in his article The Web of Word of Mouth, published in Fortune magazine in 1954 (Sormunen, 2009). As one of the earliest definition, Arndt (1967: 5) defined WOM as oral, personto-person communication between a perceived non-commercial communicator and a receiver concerning a brand, a product, or a service offered for sale. Buttle (1998) included organizations to Arndts brand, product or service component and identified electronic bulletin boards as a medium used for WOM communication. Brown et al., (2005: 125) give a broader definition: WOM is that information about products, services, stores, companies, and so on can spread from one consumer to another. In its broadest sense, WOM communication includes any information about a target object (e.g., company, brand) transferred from one individual to another either in person or via some communication medium while East et al. (2008: 215) defines WOM shortly as informal advice passed between consumers. 1.2. The Importance of WOM Pruden & Vavras (2004: 26-27) research shows that the value of word of mouth has three stages of the process: awareness, information gathering, and decision-making. Except for the awareness stage, where personal media cant touch the reach of the mass media (almost 80%), word of mouth is the source most relied on by consumers to get information by more than 60% and make decision by more than 65%.

For individuals, Rogers (1983) states that WOM helps to reduce risks at time of purchase. Furthermore, Bristor (1990) WOM enables consumers to make comparisons between or among service alternatives, or to increase understanding prior to delivery and consumption of the service. Lastly, Zeithaml et al.(1993) informs that WOM provides vital information about a firm to consumers that often times help consumers decide whether or not to patronize a firm (Dumas, 2010: 1). On product level, WOM communications often have a strong impact on product judgments because information received in a face-to-face manner is more accessible than information presented in a less vivid manner (Herr et al. 1991: 460). On firm level, WOM is viewed as being part of firm loyalty (Zeithaml & Parasuraman, 1996: 34). As noted by Aker (1991), the real value of those customers most loyal to a firm (customer loyalty), is not so much the business that they personally generate but rather their impact on others in the marketplace. Evaluations of consumption experiences are apparently affected by previously received WOM, despite ones own experience with a product or service provider (Wangenheim & Bayon, 2003: 219). Understanding WOM is becoming more important because, traditional forms of communication appear to be losing effectiveness. For example, one survey shows that consumer attitudes toward advertising decreased between September 2002 and June 2004. (Trusov et al., 2009: 90). Moreover, by internet, the growing popularity of social network sites and blogs expands the availability of WOM in the marketplace (Brown et al., 2005: 124; Dumas, 2010: 1). It is also worthful to mention that over 40% of American consumers actively seek the advice of family and friends when shopping for services such as doctors, lawyers, and auto mechanics (Hogan et al., 2004: 3). Shalback (2005: 6), states that WOM influences consumers grocery, apparel, electronics, and home improvement products shopping decisions by 31%, 26%, 35%, and 26% respectively. Lastly, Allsop et al. (2007: 398) find that, in 2006, U.S. consumers were asked which information sources they find useful when deciding which products to buy in four common product categories. WOM and "recommendations from friends / family /people at work /school" were by far the most influential sources for fast food, cold medicine, and breakfast cereal. For personal computers, a highly technical category, we saw a strong reliance on expert advice in the form of product reviews and websites, followed by WOM as the next most useful. 1.3. Types of WOM 1.3.1. Positive WOM (PWOM) Marketers are naturally interested in promoting positive WOM (PWOM), such as recommendations to others. PWOM might include making others aware that one does business with a company or store, making positive recommendations to others about a company, extolling a company's quality orientation, and so on (Brown et al., 2005: 125).

PWOM that is spread by loyal customers increases customers profitability, because PWOM attracts new customers. Positive WOM not only reduces the need for marketing expenditures but might also increase revenue if new customers are attracted. Companies that have a successful pool of PWOM have to make less effort in marketing. For instance, Starbucks, Cheesecake Factory, Jet Blue, Chick-fil-A and Harley-Davidson are assisted by delighted customers to the point that they can spend very little on advertising. These firms let their customers do their selling for them, making their brand marketing challenge easier overall (Goodman, 2005) which was confirmed by US Office of Consumer Affairs that, on average, satisfied customers relate their story to an average of five other people (Mangold, 1999: 73) 1.3.2. Negative WOM (NWOM) Negative WOM can be considered to be one of the forms of customer complaining behavior (Derbaix & Vanhamme, 2003: 100). When a consumer suffers dissatisfaction and is not consoled by the offending organization, he/she is motivated to initiate negative word of mouth as a form of retribution. An opposite, pleasant experience is enjoyable on its own and probably doesnt prompt the same level of activity. Conventional wisdom would lead us to conclude that negative word of mouth probably exceeds positive word of mouth (Pruden & Vavra, 2004: 26). Although there is little evidence, it appears that marketers believe that NWOM has more impact than PWOM. For example, Assael (2004, cited by East et al, 2008) states, Negative word of mouth is more influential than positive word of mouth (though this claim may conflate relative incidence and relative impact). Conventions in media publicity also support the idea that negative information is more potent. According to the Kroloff (1988, cited by East et al, 2008) principle, negative copy is four times as persuasive as positive copy. US Office of Consumer Affairs noted that one dissatisfied customer could be expected to tell nine other people about the experiences that resulted in the dissatisfaction (Mangold, 1999: 73). Gelb & Johnson (1995: 55) state that consumers of medical care are more likely to engage in negative word of mouth than they are to complain to their health care provider. NWOM has been shown to reduce the credibility of a companys advertising (Derbaix & Vanhamme, 2003: 100). Moreover, Arndt (1967: 292) concluded that persons receiving NWOM comments about a product were 24% less likely to purchase the product than other individuals. In consumer settings, negative information tends to be more diagnostic or informative than positive or neutral information. Negative attributes strongly imply membership in one category (i.e., low quality) to the exclusion of others, whereas positive or neutral attributes are more ambiguous with respect to category membership. Positive and neutral features are associated with many high, medium, and low-quality products. Negative features, on the other hand, have stronger implications for categorization. Even when

many positive features are exhibited (e.g., the soup has fresh meat, fresh Grade-A potatoes, and fresh vitamin-rich vegetables), a single extremely negative feature (e.g., the broth is rancid) can be highly informative. Consequently, negative-attribute information is weighted heavily in judgement (Herr et al., 1991: 460).

2. ELEMENTS of WOM 2.1. The effect of senders expertise about the product Expertise can be defined as the extend to which the source is perceived as being capable of providing correct information, and expertise is expected to induce persuasion because receivers have little motivation to check the veracity of the sources assertions by retrieving and rehearsing their own thoughts. Specifically, if the senders expertise is high, the receiver, in attempting to attain information via WOM, will more actively seek the information from a sender who is perceived as having a high level of expertise. Conversely, it can also be purported that if the senders level of expertise is perceived as low, the receiver would be less inclined to seek information from him or her (Bansal & Voyer, 2000: 169). Mei-zhi Zhang (2006: 43) investigates on the positive word of mouth that came from the sender who holds high expertise will have the effect on the receivers behavior in hair salon industry, in Thailand and Taiwan than the one who did not hold these characteristics. The analysis results show positive relationship therefore, the researcher concludes that if word of mouth sender who the receiver perceive as holding high expertise tell them about the good thing about another hair salon shop, in Thailand and Taiwan, this information would effect on their decision to switch to that service provider. Wangenheim & Bayon (2004: 1180) indicate that as perceived source expertise increases, the influence of a WOM switching referral increases. 2.2. The effect of receivers expertise about the product Bansal &Voyer (2000: 175) states that receivers expertise is found to be a significant indicator of the amount of risk that he/she will perceive. They conclude that the higher the expertise, the lower the risk. The more someone is knowledgeable or possesses experience, the less risky will be perceived by him/her. In addition, the greater the perceived risk, the more active the search for WOM information. The seeker's expertise appears to have a direct negative effect on the seeker's preference for WOM information when consumer durables are involved. it appears that seeker

expertise does not lessen the influence of a source when non-durables and services are included in the analysis. This finding supports the idea that lower financial risk for purchasing many of these non-durable products may lead to more variety seeking, which increases source influence, even when the seeker possesses expertise. (Gilly et al., 1998: 93) Mei-zhi Zhang (2006: 44) states that receivers expertise and the influence of the sender word of mouth have no relationship in hair salon industry (for both Thailand and Taiwan respondents). 2.3. Tie strength between sender and receiver The tie strength of a relationship is defined as strong if the sources of someone who knows the decision maker personally (Duhan et al., 1997: 284). Tie strength is a multidimensional construct that represents the strength of the dyadic interpersonal relationships in the context of social networks (Money et al., 1998: 79). Tie strength has been found to be one of the most significant factors explaining the influence of WOM communications (De Bruyn & Lilien, 2008: 153). It is indicated by several variables such as the importance attached to the social relation, frequency of social contact, and type of social relation, e.g., close friend, acquaintance (Brown & Reingen, 1987: 351). The research of Brown & Reingen (1987) indicates that strong ties bear greater influence on the receivers behavior than weaker ties. Bansal & Voyer (2000: 174) concludes that the greater the strength of the tie between the sender and the receiver, the greater the influence of the senders WOM on the receivers purchase decision. Mei-zhi Zhang (2006: 44-45) investigates that when the WOM sender who has the strong tie with the receiver, provide the positive information about the hair salon shop, this information may lead to the result in receivers switch to new service provider. This strong tie relationship could lead to friends and relative, marketer could learn to use this tie in developing market strategies. De Bruyn & Lilien, (2008: 159-160) find that characteristics of the social tie influences recipients' behaviors, but have different effects at different stages (stages are awareness, interest, and final decision): tie strength facilitates awareness, perceptual affinity triggers recipients' interest, and demographic similarity has a negative influence on each stage of the decision-making process. Tie Strength significantly influences the decision of the recipient to open the e-mail he or she received, hence facilitating awareness. 2.4. The receivers perceived risk on the influence of WOM Perceived risk is defined as the degree of uncertainty perceived by the consumer as to the outcome of a specific purchase decision. Perceived risk types are composed of 6 risks:

functional, financial, physical, psychological, social, and time (Brugess, 2003: 261; Kilicer, 2006:57; Wangenheim & Bayon, 2004: 1176). According to Bansal & Voyer (2000), some service bear higher levels of perceived risk. For example, medical care would likely have higher risk than the selection of a restaurant. Likewise, Zeithaml & Bitner (1990), emphasize the role of risk in the service encounter. They indicate that there is a higher level of risk associated with the purchase of services, primarily because services are intangible, nonstandardized and usually sold without guarantiees and warranties (Bansal & Voyer, 2000: 168-169). For consumer durables, which tend to involve the greatest financial and functional risks and increased length of purchase cycle, Seeker expertise lessened the ability to be influenced. It appears that Seeker expertise does not lessen the influence of a Source when non-durables and services are included in the analysis. This finding supports the idea that lower financial risk for purchasing many of these non-durable products may lead to more variety seeking, which increases Source influence, even when the Seeker possesses expertise. (Gilly et al., 1998: 93). 3. RESEARCH and FINDINGS 3.1. The research, the model, and the sample size It is important to note that this research takes Kilicer (2006)s masters thesis research, done on academicians at Anadolu University, as the reference. We aim to explore Kirklareli Universitys academicians purchasing decisions, the factors related to WOM, the effect of senders and receivers expertise about the product/service, tie strength between sender and receiver, the receivers perceived risk on the influence of WOM, and the identification of information sources which affect academicians buying decision, apart from WOM by redoing Kilicers (2006) research and also we want to compare the findings with the original study. As Kilicer (2006) have done, in this research the authors have used descriptive and associative research model. Kirklareli University was established in 2007 in Kirklareli City/Turkey. It has 4 faculties, a college, and 7 vocational schools. The university has 250 academicians. The authors wanted to reach at least half of them but only 90 academicians answered the survey- 36% return rate. SPSS 11,5 was used to analyze the data. 3.1.1. Questionnaire The questionnaire, composed of 28 questions, was taken from Kilicers thesis. Questions 1-3 were related with the purchased product influenced by WOM, whether the information about the product was demanded by the receiver or not, and tie strength.

Questions dealt with tie strength originally taken from Frenzen & Davis (1990). Senders expertise was from Frenzen & Nakamoto (1993). Receivers expertise and perceived risk were taken from Bansal & Voyer (2000). The level of effect was from Bansal & Voyer (2000), Ocass & Grace (2004), and Gilly et al. (1998) . For these 19 statements 5-point Likert Scale was used.1: the lowest and 5: the highest response. Last 4 question were related with the demographical characteristics of the academicians. 3.2. Findings Due to the fact that the full paper must be maximum 15 pages, the authors decided to give tables, figures, or graphics in lesser extent. 3.2.1. Demographical Characteristics The gender of the surveyors was composed of 42,2% female and 57,8% male. The age profile was young. 5,6% was below 24 years. The highest percentage belonged to age interval of 25-34 with 58,9%. The second highest ratio was 26,7% which is the interval of 35-44 years old.The least one was higher than 55 years old academicians with 3,3%. 52,2% of the participants was married while 47,8% was single. Lastly, none of the professors partipated the survey. Only 1 associate profesor (1,1%) , 8 assistant professors (8,9%), 60 instructors (66,7%), 15 assistants (16,7%), and 6 lecturers (6,7%) returned the questionaire. 3.2.2. WOM Information demanded by respondents 79% of the respondents demand WOM information while 21% do not. The results are similar to Kilicers findings which are 80% and 20%. 3.2.3. Closeness between the receiver and the sender The first place belongs to friends by 58%. Different from Kilicer (colleagues 23% as the second), relatives come as the second by 12%. Colleagues, other, anyone, parents, spouse, neighbor follow the relatives by 11%, 6%, 4%, 3%, 3%, and 2% respectively. It can be inferred that respondents use WOM communication with their friends and relatives. It is interesting that anyone meet coincidently has higher rank than parents or spouse. 3.2.4. Tie strength The answers are similar to Kilicers findings except spending time. The level of sharing the secret and help requested if needed and the level of spending time between receiver and sender have high level.

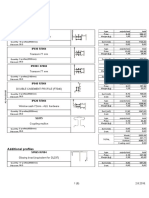

Table 3. 1 . Tie Strength

Tie Strength between Receiver &Sender Sharing his/her secret Spending time with him/her Help request if needed Very High Frequency Percentage/K% 21 23,3/21.2 16 17,8/12,9 High Frequency Percentage/K% 24 26,7/26.7 20 22,2/25,5 Normal Frequency Percentage/K% 15 16,7/25,9 19 21,1/34,5 Low Frequency Percentage/K% 13 14,4/26.7 14 15,6/15,7 Very Low Frequency Percentage/K% 17 18,9/21,2 21 23,3/11,4

19 21,1/27,5

26 28,9/31

20 22,2/17,6

12 13,3/12,9

13 14,4/11

n:90; K%: % that Kilicer found in the original study 3.2.5. The senders expertise The results are similar to Kilicers findings except the level of senders education/expertise about the product. The levels of senders knowledge about the product, senders education/expertise about the product, and senders experience with the product as a user have high level. Table 3.2. The senders expertise

The senders expertise Very High Frequency Percentage/ K% 35 38,9/32 19 21,1/19 38 42,2/37 High Frequency Percentage/ K% 36 40/46 26 28,9/24 40 44,4/45 Normal Frequency Percentage/ K% 15 16,7/20 20 22,2/30 9 10/13 Low Frequency Percentage/ K% 4 4,4/2 12 13,3/14 1 1,1/2 Very Low Frequency Percentage/ K% 0 0/0 13 14,4/13 2 2,2/4

Senders knowledge about the product Senders education/expertise about the product Senders experience with the product as a user

n:90; K%: % that Kilicer found in the original study 3.2.6. The receivers expertise In Table 3.3., the level of receivers expertise on the product is given. Each level has normal level like the original study.

Table 3.3. The Receivers expertise

The Receivers expertise Very High Frequency Percentage/ K% 5 5,6/9 8 8,9/3 6 6,7/8 High Frequency Percentage/ K% 35 38,9/37 27 30/15 15 16,7/30 Normal Frequency Percentage/ K% 38 42,2/41 27 30/38 27 30/37 Low Frequency Percentage/ K% 10 11,1/11 25 27,8/26 25 27,8/16 Very Low Frequency Percentage/ K% 2 2,2/3 3 3,3/17 17 18,9/9

Receivers knowledge level Receivers education/expertise about the product Receivers experience with the product as a user

n:90; K%: % that Kilicer found in the original study 3.2.7. Perceived risks Perceived risks levels are given in Table 3.4. According to the results, financial and performance risks perceived have normal level, but the other risks have very low level. The results are consistent with the Kilicers findings. Table 3.4. Perceived risks

Perceived risks Very High Frequency Percentage/ K% 15 16,7/8 19 21,1/8 6 6,7/4 6 6,7/1 9 10/3 8 8,9/4 High Frequency Percentage/ K% 14 15,6/34 15 16,7/28 13 14,4/11 6 6,7/5 15 16,7/10 12 13,3/10 Normal Frequency Percentage/ K% 41 45,6/35 30 33,3/31 14 15,6/21 15 16,7/9 24 26,7/24 18 20/22 Low Frequency Percentage/ K% 13 14,4/18 17 18,9/28 28 31,1/33 12 13,3/24 17 18,9/29 18 20/32 Very Low Frequency Percentage/ K% 7 7,8/4 9 10/6 29 32,2/31 51 56,7/62 25 27,8/34 34 37,8/33

Financial Risk Performance Risk Physical Risk Social Risk Psychological Risk Technical Risk

n:90; K%: % that Kilicer found in the original study 3.2.8. The effect of WOM Like the Kilicers findings, the results show that WOM has high level of influence. Table 3.5. The Effect of WOM

The effect of WOM Very High High Normal Low Very Low

10

Level of information obtained from the sender Level of identification not considered before Level of help obtained by Sender to purchase The effect of Sender on Purchase Decision

Frequency Percentage/ K% 18 20/19 18 20/17 29 32,2/27 25 27,8/31

Frequency Percentage/ K% 42 46,7/53 35 38,9/41 36 40/48 39 43,3/44

Frequency Percentage/ K% 25 27,8/25 21 23,3/28 18 20/20 20 22,2/19

Frequency Percentage/ K% 4 4,4/3 13 14,4/11 5 5,6/3 3 3,3/4

Frequency Percentage/ K% 1 1,1/1 3 3,3/3 2 2,2/2 3 3,3/2

n:90; K%: % that Kilicer found in the original study 3.2.9. The correlation between tie strength and effect of WOM and senders expertise and effect of WOM Correlation analysis shows positive, significant, and medium level relationship (r=0,359, r2=0.129, p<.01) between tie strength and effect of WOM. According to the result,13% of the effect of WOM is caused by tie strength between the receiver and the sender while it was 3% in Kilicers study. Correlation analysis (Pearson correlation) indicates positive, significant, and medium level relationship (r=0,463, r2=0.215, p<.01) between senders expertise and effect of WOM. According to the result, 22% of the effect of WOM is caused by senders expertise While it was 24% in Kilicers study. 3.2.10. The correlation between receivers expertise and effect of WOM and perceived risks and effect of WOM Correlation analysis does not indicate any significant relationships (r=0,018, p>.05) between receivers expertise and effect of WOM and between perceived risks and effect of WOM (r=0,006, p>.05). 3.2.11. Information sources apart from WOM As consistent with Kilicer, the internet has the highest percentage of 67%, followed by other sources 9%, salesman 8%, catalog 7%, press-news-comments 6%, and advertisement 4%. 3.2.12. The most influential information source Like Kilicers findings, the most influential information source is WOM (56%) followed by internet (27%).These findings show the importance of WOM and internet as information source which affect purchasing decision of academicians at Kirklareli University. Less than 10% sources are other 8%, press, news and comments 4%, salesman 3%, advertisement and catalog 1,1%

11

3.2.13. ANOVA for determining any differences depending on demographics ANOVA (Tukey HSD) has been used to determine any difference depending on demographical characteristics. ANOVA shows only differences between perceived risk level and age. It means that there is no difference among tie strength, senders or receivers expertise, effect of WOM and age, marital status, gender, and title. Differences shown are between the age and social, psychological, and technical risks. 3.2.13.1. Social and psychological risks and age The differences are between 25-34 and 45-54 and between 35-44 and 45-54. Therefore, not being as linear, the level of social psychological, and technical risks belong to age between 45-54 has the highest level (mean: 3,4; 4,2) followed by age between 25-34 (mean: 1,8; 2,5) and 35-44 (mean: 1,6; 2,3) 3.2.13.2. Technical risk and age The differences are between 25-34 and 45-54. Therefore, not being as linear, the level of technical risk belongs to age between 45-54 has the highest level (mean: 4,0) followed by age between 25-34 (mean: 2,2). 4. CONCLUSION, LIMITATIONS, and FURTHER RESEARCH In this study, the definition, the importance of WOM, and its types, elements of WOM such as the effect of senders and receivers expertise about the product, tie strength between sender and receiver, the receivers perceived risk on the influence of WOM, and the findings, compared with the Kilicers study, were examined on academicians at Kirklareli University. Findings and implications for managers can be summarized as follows: 79% of the respondents demanded WOM information. It is clear to say that WOM communication to purchase a product started with the receivers demand. Friends were chosen (58%) as WOM communicators. Tie strength between receiver and sender was high. They shared their secrets, spent time together, and requested help each others highly. Correlation analysis showed positive, significant, and medium level relationship between tie strength and effect of WOM. The levels of senders knowledge about the product, senders education/expertise about the product, and senders experience with the product as a user have high level. Moreover, correlation analysis indicated positive, significant, and medium

12

level relationship between senders expertise and effect of WOM. It could be inferred that respondents asked their friends who were more experienced/knowledgeable about the product they interested in. Therefore, it would be a good idea for marketing managers who might reach opinion leaders. Preparing parties, seminars, delivering trial products for opinion leaders would be a way to reach opinion leaders. As receivers expertise, each statement and so the condition had normal level and no correlation was found between receivers expertise and effect of WOM. Financial and performance risks perceived had normal level, but the other risks had very low level. Moreover, correlation analysis indicated no significant relationship between perceived risks and effect of WOM Therefore, perceived risks did not play important role. The results showed that WOM had high level of influence. The internet had the highest percentage of 67%, apart from WOM, as an information source. As stated in Kilicers study, customers get information about the product by using internet in two basic ways: The first way is to visit producers website to learn/check product features, prices, paying conditions etc. The second way is to surf in the internet to get information about products by visiting blogs, forums, complaint sites etc. which can be called as e-WOM. Therefore, firms should check and control these platforms. Even they establish blogs for their products including advantages or disadvantage of the products given by users. We supported Kilicers study that most influential information source was WOM (56%) followed by internet (27%). Unlike Kilicers study (not reported in the study), ANOVA showed us that there were differences between perceived risk level and age. The differences shown were between the age and social, psychological, and technical risks. Not being as linear, the levels of social, psychological, and technical risks belonged to age between 45-54 had the highest level.

There are some limitations associated with this study. Most of them were stated in the original study. First is related with the sample. The sample is composed of academicians working at Kirklareli University that is an important obstacle to generalize the findings. But our findings are consistent with and do support the findings by Kilicer related with high level educated peoples WOM communication. Second, none of the professors responded. Third, other influential factors related with WOM such as personal characteristics of sender and receiver, similarities between sender and receiver were not examined in this study. Fourth, the effect of internet or web based blogs, forums were not covered. We suggest researchers to consider these limitations and offer to find out generalizable results.

13

REFERENCES Allsop, D., Basset, B.R. & Hoskins, J.A. (2007), Word-of-Mouth Research: Principles and Applications, Journal Of Advertising Research, December, pp.398-411 Arndt, J. (1967), Role of Product-Related Conversations in the Diffusion of a New Product, Journal of Marketing Research (JMR), 4(3), 291-295. Bansal, H. S. & Voyer, P.A. (2000), Word-of-Mouth Processes within a Services Purchase Decision Context, Journal of Service Research, 3(2), 166. Brown, T., Barry, T., Dacin, P., & Gunst, R. (2005). Spreading the word: investigating antecedents of consumers positive word-of-mouth intentions and behaviors in a retailing context. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , 33 (2), 123-138. Brown, J. J. & Reingen, P.H. (1987), "Social Ties and Word-of-Mouth Referral Behavior," Journal of Consumer Research, 14 (3), 350-62. Brugess, B. (2003). A Comparison of TV Home Shoppers Based on Risk Perception, Journal of Fasion Marketing and Management, Vol.7, No.3, pp.259-271 Buttle, Francis A.(1998) 'Word of mouth: understanding and managing referral marketing', Journal of Strategic Marketing, 6: 3, 241 254 De Bruyn, Arnaud and Lilien, G.L. (2008), A Multi-Stage Model of Word of Mouth Through Viral Marketing, International Journal of Research in Marketing, 25 (3), 143 225. Derbaix, C. & Vanhamme, J.(2003). Inducing word-of-mouth by eliciting surprise a pilot investigation, Journal of Economic Psychology, 24, pp. 99116 Duhan, D. F., S. D. Johnson, J. B. Wilcox and G. D. Harrell (1997), Influences on Consumer Use of Word of Mouth Recommendation Sources, Journal of the academy of Marketing Science, 25(4), 283-295. Dumas, L.V. (2010), The effect of Received Word-of-Mouth on Given Word-of-Mouth: Cross level effects of Firm and Product Received Word-of-Mouth, TUE. Series Master Theses Innovation Management, nr.1. Department Industrial Engineering & Innovation Sciences, Eindhoven East, R., Hammond, K., & Lomax, W. (2008). Measuring the Impact of Positive and Negative Word of Mouth on Brand Purchase Probability. International Journal of Research in marketing , 25, 215-224. Erez, T., Moldovan, S. & Solomon, S. (2005). Social Anti-Percolation and Negative Word of Mouth, http://arxiv.org/abs/cond-mat/0406695v2 (05-29-2010) Frenzen, Jonhatan K. and Harry L. Davis (1990), "Purchasing Behavior in Embedded Markets," Journal of Consumer Research, 17. Gelb, B. & Johnson, M. (1995). Word of Mouth Communication: Causes and Consequences. Marketing Review. Vol.15, No.3. Goodman, J. (2005). Top of Mind: Treat Your Customers As Prime Media Reps http://www.brandweek.com/bw/esearch/article_display.jsp? vnu_ content_id= 1001096163 (05-27-2010)

14

Harrison-Walker, L. (2001). The measurement of word-of-mouth communication and an investigation of service quality and customer commitment as potential antecedents. Journal of Service Research , 4 (1), 60-75. Herr, P., Kardes, F., & Kim, J. (1991). Effects of word-of-mouth and product attribute information on persuasion: an accessibility-diagnosticity perspective. Journal of Consumer Research , 17, 454-462. Kler, T. (2006). Tketicilerin Satnalma Kararlarnda Azdan Aza letiimin Etkisi: Anadolu niversitesi retim Elemanlar zerinde Bir Aratrma, Yaynlanmam Master Tezi, Anadolu niversitesi, Eskiehir. Mangold, W. G., Miller, F., and Brockway, G.R. (1999). Word of Mouth Communication in the Service Marketplace. Journal of Services Marketing. Vol.13, No.1, s.73-89. Mazzarol, T., Sweeney, J., & Soutar, G. (2007). Conceptualizing word-of-mouth activity, triggers and conditions: an exploratory study. European Journal of Marketing , 41 (11/12), 1475-1494. Mei-zhi Zhang, Khemjira Apiraknukornchai (2006). The effect of Positive Word of Mouth on consumer Switching Behavior: a Double Research Study in Thailand and Taiwan Hair Salon Service, etd-0505106-165603.pdf (05-20-2010) Money, R. B., Mary C. Gilly and John L. Graham (1998), Explorations of National Culture and Word of Mouth Referral Behavior in the Purchase of Industrial Services in the United States and Japan, Journal of Marketing, 62(4), 76-87. Pruden, D. & Vavra, T.G. (2004). Controlling the Grapevine. Marketing Management. Vol. 13, Issue 4, July-August. Shalback, Linda. Majority Rules. Marketing Management. Vol.14, Issue 2, MarchApril, 2005 Silverman, G.(2001). The Secrets of Word of Mouth Marketing. New York: American Management Association Sormunen, V. (2009). International Viral Marketing Campaign Planning and Evaluation, Department of Marketing and Management, Helsinki School Of Economics Trusov, M., Bucklin, R., & Pauwels, K. (2009). Effects of word-of-mouth versus traditional marketing: findings from an internet social networking site. Journal of Marketing , 73 , 90-102. Wangenheim, F. V. & Bayon, T. (2003). Satisfaction, loyalty and word of mouth within the customer base of a utility provider: Differences between stayers, switchers and referral switchers, Journal of Consumer Behavior Vol. 3, 1, 211220 Wangenheim, F. V. & Bayon, T. (2004). The Effect of Word of Mouth on Services Switching: Measurement and Moderating Variables. European Journal of Marketing. Vol.38, Issue 9/10. Zeithaml, V., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing , 60 (2), 31-46.

15

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Sem13 PDFDocument132 pagesSem13 PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Positive vs. Negative Online Buzz On Retail PricesDocument36 pagesThe Impact of Positive vs. Negative Online Buzz On Retail PricesdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Springer81 PDFDocument11 pagesSpringer81 PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Sem20 PDFDocument123 pagesSem20 PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Sem21 PDFDocument107 pagesSem21 PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Shin2011-Impact of Positive vs. Negative E-Sentiment On Daily Market Value of High-Tech Products PDFDocument38 pagesShin2011-Impact of Positive vs. Negative E-Sentiment On Daily Market Value of High-Tech Products PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Sem19 PDFDocument21 pagesSem19 PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Investigating The Impact of C2C Electronic Marketplace Quality On TrustDocument69 pagesInvestigating The Impact of C2C Electronic Marketplace Quality On TrustdanikapanNo ratings yet

- SEM16Document134 pagesSEM16danikapanNo ratings yet

- Newarticle18socialaug12 PDFDocument12 pagesNewarticle18socialaug12 PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- E-Voicing An Opinion On A Brand: Marc - Filser@Document22 pagesE-Voicing An Opinion On A Brand: Marc - Filser@danikapanNo ratings yet

- Online Influencers in Long Tail MarketsDocument51 pagesOnline Influencers in Long Tail MarketsdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Sem12 PDFDocument25 pagesSem12 PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Sem1 PDFDocument35 pagesSem1 PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Semantic Web On Decision Making of Customers in Tourism IndustryDocument22 pagesThe Influence of Semantic Web On Decision Making of Customers in Tourism IndustrydanikapanNo ratings yet

- Sem6 PDFDocument23 pagesSem6 PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of The Effect of Online Consumer Trust On Expectation, Satisfaction, and Post-ExpectationDocument22 pagesAn Investigation of The Effect of Online Consumer Trust On Expectation, Satisfaction, and Post-ExpectationdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Research On Facebook Etc PDFDocument20 pagesResearch On Facebook Etc PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Mining Messages: Exploring Consumer Response To Consumer-Vs. Firm-Generated AdsDocument9 pagesMining Messages: Exploring Consumer Response To Consumer-Vs. Firm-Generated AdsdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Sem7 PDFDocument28 pagesSem7 PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Gina A. Tran David Strutton David G. Taylor: Title: Author(s)Document18 pagesGina A. Tran David Strutton David G. Taylor: Title: Author(s)danikapanNo ratings yet

- Newarticle20socialaug12 PDFDocument10 pagesNewarticle20socialaug12 PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Pang2009-Consumer Response To Marketing Communications PDFDocument89 pagesPang2009-Consumer Response To Marketing Communications PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Forward or Delete: What Drives Peer-To-Peer Message Propagation Across Social Networks?Document8 pagesForward or Delete: What Drives Peer-To-Peer Message Propagation Across Social Networks?danikapanNo ratings yet

- Kim2009-Impacts of Blogging Motivation and Flow On Blogging Behavior PDFDocument107 pagesKim2009-Impacts of Blogging Motivation and Flow On Blogging Behavior PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Forward or Delete: What Drives Peer-To-Peer Message Propagation Across Social Networks?Document8 pagesForward or Delete: What Drives Peer-To-Peer Message Propagation Across Social Networks?danikapanNo ratings yet

- Participatory Communication With Social Media: CuratorDocument11 pagesParticipatory Communication With Social Media: CuratordanikapanNo ratings yet

- Newarticle19socialaug12 PDFDocument9 pagesNewarticle19socialaug12 PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Newarticle13socialaug12 PDFDocument9 pagesNewarticle13socialaug12 PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- In Search of The "Meta-Maven": An Examination of Market Maven Behavior Across Real-Life, Web, and Virtual World Marketing ChannelsDocument19 pagesIn Search of The "Meta-Maven": An Examination of Market Maven Behavior Across Real-Life, Web, and Virtual World Marketing ChannelsdanikapanNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 2 Islm WBDocument6 pages2 Islm WBALDIRSNo ratings yet

- Amy Kelaidis Resume Indigeous Education 2015 FinalDocument3 pagesAmy Kelaidis Resume Indigeous Education 2015 Finalapi-292414807No ratings yet

- Final Draft Investment Proposal For ReviewDocument7 pagesFinal Draft Investment Proposal For ReviewMerwinNo ratings yet

- Lista Materijala WordDocument8 pagesLista Materijala WordAdis MacanovicNo ratings yet

- By Nur Fatin Najihah Binti NoruddinDocument7 pagesBy Nur Fatin Najihah Binti NoruddinNajihah NoruddinNo ratings yet

- Case Digest Labor DisputeDocument5 pagesCase Digest Labor DisputeMysh PDNo ratings yet

- Mock Exam 2Document18 pagesMock Exam 2Anna StacyNo ratings yet

- Caucasus University Caucasus Doctoral School SyllabusDocument8 pagesCaucasus University Caucasus Doctoral School SyllabusSimonNo ratings yet

- BA BBA Law of Crimes II CRPC SEM IV - 11Document6 pagesBA BBA Law of Crimes II CRPC SEM IV - 11krish bhatia100% (1)

- Adventure Shorts Volume 1 (5e)Document20 pagesAdventure Shorts Volume 1 (5e)admiralpumpkin100% (5)

- Reflection IntouchablesDocument2 pagesReflection IntouchablesVictoria ElazarNo ratings yet

- Incremental Analysis 2Document12 pagesIncremental Analysis 2enter_sas100% (1)

- Equilibrium of Firm Under Perfect Competition: Presented by Piyush Kumar 2010EEE023Document18 pagesEquilibrium of Firm Under Perfect Competition: Presented by Piyush Kumar 2010EEE023a0mittal7No ratings yet

- Experiment No 5 ZenerDocument3 pagesExperiment No 5 ZenerEugene Christina EuniceNo ratings yet

- Parathyroid Agents PDFDocument32 pagesParathyroid Agents PDFRhodee Kristine DoñaNo ratings yet

- Schedule Risk AnalysisDocument14 pagesSchedule Risk AnalysisPatricio Alejandro Vargas FuenzalidaNo ratings yet

- Food Corporation of India Zonal Office (N) A-2A, 2B, SECTOR-24, NOIDADocument34 pagesFood Corporation of India Zonal Office (N) A-2A, 2B, SECTOR-24, NOIDAEpaper awaazNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia Considerations in Microlaryngoscopy or Direct LaryngosDocument6 pagesAnesthesia Considerations in Microlaryngoscopy or Direct LaryngosRubén Darío HerediaNo ratings yet

- Projectile Motion PhysicsDocument3 pagesProjectile Motion Physicsapi-325274340No ratings yet

- Problem-Solution Essay Final DraftDocument4 pagesProblem-Solution Essay Final Draftapi-490864786No ratings yet

- Book - IMO Model Course 7.04 - IMO - 2012Document228 pagesBook - IMO Model Course 7.04 - IMO - 2012Singgih Satrio Wibowo100% (4)

- A Social Movement, Based On Evidence, To Reduce Inequalities in Health Michael Marmot, Jessica Allen, Peter GoldblattDocument5 pagesA Social Movement, Based On Evidence, To Reduce Inequalities in Health Michael Marmot, Jessica Allen, Peter GoldblattAmory JimenezNo ratings yet

- DIALOGUE Samples B2 JUNE EXAMDocument4 pagesDIALOGUE Samples B2 JUNE EXAMIsabel María Hernandez RuizNo ratings yet

- AUTONICSDocument344 pagesAUTONICSjunaedi franceNo ratings yet

- GCF and LCMDocument34 pagesGCF and LCMНикому Не Известный ЧеловекNo ratings yet

- Last Speech of Shri Raghavendra SwamyDocument5 pagesLast Speech of Shri Raghavendra SwamyRavindran RaghavanNo ratings yet

- Donchian 4 W PDFDocument33 pagesDonchian 4 W PDFTheodoros Maragakis100% (2)

- Ethiopia FormularyDocument543 pagesEthiopia Formularyabrham100% (1)

- Part 4 Basic ConsolidationDocument3 pagesPart 4 Basic Consolidationtαtmαn dє grєαtNo ratings yet

- GMAT2111 General Mathematics Long Quiz 2Document2 pagesGMAT2111 General Mathematics Long Quiz 2Mike Danielle AdaureNo ratings yet