Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Why Music Piracy Should Be Legal

Uploaded by

Matt RosenthalOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Why Music Piracy Should Be Legal

Uploaded by

Matt RosenthalCopyright:

Available Formats

Matthew Rosenthal December 11, 2013 English 1010 Honors Music Piracy Didnt Kill the Recording Artist

Since the invention of the Internet, an enormous amount of information and media has been made available to the general public. In their lawsuit against Napster, Metallica complained, It is sickening to know that our art is being traded like a commodity rather than the art that it is.1 However, record companies tried to fight rather than to adapt to the quickly changing situation: music was being shared by thousands of people on a daily basis. Since then, many arguments have been made against music downloading. The most common of which is that stealing is stealing; it is simply not right to take someone elses work without paying for it. A less moralistic but more misguided has been put forth by Rick Carnes in his article Has Music Piracy Killed the Recording Artist. Carnes argues that the real recording artists are gone because of music downloading. However, he is wrong in equating less attention paid to record sales is with less attention paid to recording. Even with music downloading, recording still holds a necessity in the careers and development of artists. Rick Carnes believes that the true recording artists are a dying breed. A recording artist is a musical person or group that focuses on recording and selling records, rather than touring. Carnes believes that music piracy is to blame for the

1

The Trouble With Napster, Richard Kwon. October, 2000. http://www.layouth.com/the-trouble-with-napster/

loss of recording artists. His logic: by taking away the monetary incentive to record an album, music pirates have forced artists to focus on the performance aspect of their musicthe showrather than the music itself. As a result, many musicians focus less on writing and recording the music and instead focus on developing hit videos. Carnes quotes Damian Kulash of the group OK Go to argue his point about the dismal future of recording. Kulash brings up an interesting point: when artists spend so much time, effort, and money on their music videos, why would they spend time on the musical aspect? Carnes also draws an analogy to this contemporary problem to a phenomenon in the 19th century. European composers were not protected by American copyright law, so their music was pirated and available cheaply for American consumers. Carnes ignores the point that the same technology that has enabled Internet music piracy has also given artists unprecedented access and ability to record their music and distribute it to wide audiences. With the technology to support highfidelity sound cards, Digital Audio Workstations (DAW), and industry standard recording equipment at affordable prices, recording artists have actually been on the rise. From the late 1990s until now, we have seen the growth of do-it-yourself music groups such as: The White Stripes, Radiohead, Oasis, and Periphery, who have used computer technology to record albums. Unknown artists, such as Keith Merrow and Tosin Abasi, have used downloading and streaming technology to reach a wider audience than would have ever been possible before the advent of broadband Internet and sophisticated home recording software.

Without a doubt, Internet music piracy has led to huge declines in record sales for artists. However, according to Timothy B. Lee, in his article, Think piracy is killing the music industry? This chart suggests otherwise, this might not be such a bad thing. Lee cites a study that suggests that although record sales have gone down since 1998, the total revenue from concerts, publishing, and mobile phone/internet music sales has increased tremendously.2 Still, Carnes believes that album sales are an afterthought. Despite artists not being able to make as much money selling their albums, recording music has remained a necessary part to promoting musicians. Indeed, it is still the best medium for artists constrained by time and space to reach a mass audience. Carnes makes a false distinction between the true recording artists and a lesser form of recording artist, which he defines vaguely as relying on home recording equipment. He writes, the studio musicians who were able to devote their lives to improving their sound and their technique are a dying breed, replaced by home recording studios and sample-looping software (Carnes 6). These home recording artists are studio musicians. As the president of the Songwriters Guild of America, Carnes should be more familiar with the quality of modern home recording technology. He should know that artists are now able to make records at home that rival any big studios quality with the added advantage that they are not physically and financially bound to a studio. In addition to this, the home recording trend is

Timothy B. Lee, Think Piracy is killing the music industry? This chart suggests otherwise. October 7, 2013. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/the-switch/wp/2013/10/07/think-piracy-is-killing-themusic-industry-this-chart-suggests-otherwise/

creating multi-talented musicians: those who can write and produce music, cutting out the middleman, the corporate record labels, engineers, and producers, and making it easier to create music. Carnes also argues that because music sales have declined, the focus for artists has shifted from creating good music to creating good music videos. This argument is not new. Alarmists have warned about the dangers of music videos since before Buggles debuted Video Killed the Radio star on MTV thirty years ago. The focus has not shifted from making music to making music videos. Yes, the music has changed, for better or for worse, from Duran Durans Hungry Like the Wolf in the 1980s to Miley Cyruss new release, Wrecking Ball. But the music still precedes the video. Even artists like OK Go who are cited by Carnes as representing this supposed shift, and who are arguably known better for their YouTube videos than for their music, cannot gain fame without the catchy songs that accompany their videos. Carnes makes a mistake similar to other doomsayers of music piracy; that is, he equates a change in production and distribution of music to the end of it. To this end, he recalls a phenomenon in the 19th century in which US songwriters had to compete with free music coming from European composers. As a result, Carnes says songwriters could make their money only through performance instead of publishing. He writes, The traveling minstrel show was the only place that Foster could eke out a few dollars (Carnes 10). Despite Fosters continued association with 19th century minstrelsy, he still managed to write some of the most lasting songs in American popular music. Artists in any medium always have to balance their needs

to grow their artistry and to make a living. Whatever Carnes wants us to think, recorded music isnt going anywhere. Just as the advent of recorded music did not destroy the live music industry, we cannot expect an increased focus on performance to destroy recording. Carnes doesnt mention record labels. However, his argument is an implicit defense of the studio system in which A&R representatives and executives picked the winners and losers in the music industry. And while this system did foster great talent, its artists perpetually sought greater freedom to create. In 1968 The Beatles created the Apple Records label to free them to produce music without corporate influence. In a similar vein, Jimi Hendrix built the Electric Lady studio. In more recent memory, artists as diverse as Pearl Jam and Lauryn Hill have complained of record labels more interested in their bottom line and stock prices than in fostering artistry. The real problem with arguments like Carness is that they rely on a myth that never really existed. Even indisputably true recording artists like Brian Wilson, The Beatles, and Bob Dylan, made their names first as performers. Its possible that home recording, digital downloads, and social media have reversed the old order from one in which performers became recording artists to one in which artists use recording to promote a performing career. So while music piracy represents a change, even a revolution, in recorded music, it is not the end of anything. As a lobbyist for the Songwriters Guild of America, Carnes represents a status quo that for many years kept new artists from achieving success and restricted the creative potential of the chosen few.

Works Cited Carnes, Rick. "Has Music Piracy Killed the 'Recording Artist'?." The Huffington Post. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/rick-carnes/has-music-piracy-killedt_b_803596.html>. Kwon, Richard. "The trouble with Napster." LA Youth RSS. <http://www.layouth.com/the-trouble-with-napster/>. Lee, Timothy. "Think piracy is killing the music industry? This chart suggests otherwise." TheHuffingtonPost. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/the-switch/wp/2013/10/07/thinkpiracy-is-killing-the-music-industry-this-chart-suggests-otherwise/>.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- G. Bomhof - Solo Pieces For TimpaniDocument23 pagesG. Bomhof - Solo Pieces For TimpaniAnita Primorac100% (2)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Infinite GuitarDocument266 pagesThe Infinite GuitarBruno Sant Anna100% (12)

- Bach BWV 847 BassvideoslessonDocument4 pagesBach BWV 847 BassvideoslessonBass Videos LessonNo ratings yet

- TagbanuaDocument4 pagesTagbanuaPatrisha Banico Diaz0% (1)

- Manuel de Falla AnalysisDocument3 pagesManuel de Falla AnalysisMatt Rosenthal100% (1)

- Saxophone TechniqueDocument0 pagesSaxophone TechniqueMagdalena Majkowska40% (5)

- Eng Proj 4 Chapters 11-21cycleDocument3 pagesEng Proj 4 Chapters 11-21cycleMatt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Bread Givers Assimilatino EssayDocument5 pagesBread Givers Assimilatino EssayMatt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Matt BrancoDocument1 pageMatt BrancoMatt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Editorial DRAFT 1Document2 pagesEditorial DRAFT 1Matt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Aurora BorealisDocument5 pagesAurora BorealisMatt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Matt R Course PlanDocument2 pagesMatt R Course PlanMatt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Yugioh Beatdown DeckDocument3 pagesYugioh Beatdown DeckMatt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Hamlet Journal Entry 4Document1 pageHamlet Journal Entry 4Matt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- AP HW4 AppeasementDocument3 pagesAP HW4 AppeasementMatt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- YesDocument9 pagesYesMatt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Hamlet Journal Entry 5Document3 pagesHamlet Journal Entry 5Matt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Economics HW 2Document2 pagesEconomics HW 2Matt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- PoemDocument5 pagesPoemMatt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Idea 11 (Proggy, Pretty, Original Mighty Mallots)Document5 pagesIdea 11 (Proggy, Pretty, Original Mighty Mallots)Matt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Economics HW 15Document2 pagesEconomics HW 15Matt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Hamlet Journal Entry 4 Part 2Document1 pageHamlet Journal Entry 4 Part 2Matt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Emoticox 2.0Document4 pagesEmoticox 2.0Matt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- A Tale of Two Cities EssayDocument3 pagesA Tale of Two Cities EssayMatt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Music History Journal 1Document2 pagesMusic History Journal 1Matt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Economics HW 2Document2 pagesEconomics HW 2Matt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Fugue, Part 1Document8 pagesFugue, Part 1Matt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Idea 48 (Polytime)Document10 pagesIdea 48 (Polytime)Matt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Quote 11.7.13Document1 pageQuote 11.7.13Matt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Prompt 11.26.13Document1 pagePrompt 11.26.13Matt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- MoMA Project ReportDocument2 pagesMoMA Project ReportMatt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Ap HW17Document2 pagesAp HW17Matt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- Joan Baez - Life Of...Document1 pageJoan Baez - Life Of...Matt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- 52 LyricsDocument1 page52 LyricsMatt RosenthalNo ratings yet

- The Content of Music ClassesDocument43 pagesThe Content of Music Classesniese kaye bronzalNo ratings yet

- Blue Öyster Cult BiographyDocument7 pagesBlue Öyster Cult BiographyfffffffffffffffrffffNo ratings yet

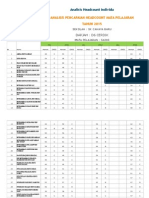

- Analisis Pencapaian Headcount Mata Pelajaran TAHUN 2015Document12 pagesAnalisis Pencapaian Headcount Mata Pelajaran TAHUN 2015Pauzan Abu BakarNo ratings yet

- Interviews Extra: Pre-Intermediate Unit 3Document3 pagesInterviews Extra: Pre-Intermediate Unit 3Max KorablevNo ratings yet

- Código Orgánico de TribunalesDocument345 pagesCódigo Orgánico de TribunalesconstanzalarenasNo ratings yet

- 2018 English Grade 11 Oral Comm Final Exam 2nd QTDocument5 pages2018 English Grade 11 Oral Comm Final Exam 2nd QTValdez FeYnNo ratings yet

- Week 10Document5 pagesWeek 10Evan Maagad LutchaNo ratings yet

- Butch 4 Butch - Rio Romeo Sheet Music For Piano (Solo) Musescore - Com 4Document1 pageButch 4 Butch - Rio Romeo Sheet Music For Piano (Solo) Musescore - Com 4Neptune AxolotlNo ratings yet

- Piano Sonata No. 11 K. 331 3rd Movement, "Rondo Alla Turca" Sheet Music For Piano (Solo)Document1 pagePiano Sonata No. 11 K. 331 3rd Movement, "Rondo Alla Turca" Sheet Music For Piano (Solo)maximoNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Aspects of Verbal Humor VerlagsversionDocument464 pagesLinguistic Aspects of Verbal Humor VerlagsversionSilvia Bogdan50% (4)

- Timberkits Accordion Instructions 4 2014Document24 pagesTimberkits Accordion Instructions 4 2014gregorio mendozaNo ratings yet

- Ilaw Sa Daan - IV of Spades (Bass Guitar)Document5 pagesIlaw Sa Daan - IV of Spades (Bass Guitar)VinSongTabs100% (2)

- British Goblins PDFDocument227 pagesBritish Goblins PDFWiam NajjarNo ratings yet

- Chopin Waltz E MinorDocument4 pagesChopin Waltz E MinorDIỆU THƯ NGUYỄN LÊNo ratings yet

- Pas de DeuxDocument17 pagesPas de DeuxVictor FloresNo ratings yet

- Pink Sweat$ - at My Worst (Easy Version)Document6 pagesPink Sweat$ - at My Worst (Easy Version)2B30 Zhang Baoxu 張宝旭 (22-23)No ratings yet

- Metodo de Violino - Sevcik - School of Violin Technic Exercises in 1st PositionDocument42 pagesMetodo de Violino - Sevcik - School of Violin Technic Exercises in 1st PositionMarco TorresNo ratings yet

- Gretsch Pricelist 2015Document28 pagesGretsch Pricelist 2015paulmarangoni100% (1)

- Por Amor - Thalia - SCOREDocument107 pagesPor Amor - Thalia - SCOREdanielNo ratings yet

- Naquela MesaDocument28 pagesNaquela MesaGustavo SampaioNo ratings yet

- SwingDocument20 pagesSwingXyrra LahipNo ratings yet

- THP CLP Project Proposal April CLP 1Document8 pagesTHP CLP Project Proposal April CLP 1Chrizel Iana MadlangbayanNo ratings yet

- Living Mice MinecraftDocument2 pagesLiving Mice MinecraftIrenitemi AgbejuleNo ratings yet

- National Artists and Their Contributions To Contemporary Arts (Music)Document15 pagesNational Artists and Their Contributions To Contemporary Arts (Music)Noel50% (4)

- BAKAS NG KAHAPON-OctavinaDocument2 pagesBAKAS NG KAHAPON-OctavinaGeod CadionNo ratings yet