Professional Documents

Culture Documents

EX LIBRIS: Commonplace Books

Uploaded by

Toronto123Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

EX LIBRIS: Commonplace Books

Uploaded by

Toronto123Copyright:

Available Formats

EX LIBRIS

A curatorial- editorial experiment by Anna-Sophie Springer The imaginary is not formed in opposition to reality as its denial or compensation; it grows among signs, from book to book, in the interstice of repetitions and commentaries; it is born and takes shape in the interval between books. It is a phenomenon of the library. ~ Michel Foucault

Ex LIBRIS

Assembled by appropriating a variety of display means found on-site, a temporary set of constellations, clusters, and visual narratives play with the book in its multidimensional role as aesthetic object and medium for the representation of information. Through ephemeral connections of image, text, and materiality, the arrangements reect the character, history, and function of these collections while relating to the surrounding architectures that house each of them. Reecting on the process and drawing comparisons between the dierent sites, EX LIBRIS culminates in a library catalogue that archives and presents the curated selections as well as the display strategies. Documentation is created with the available on-site means of reproduction (the photocopier, scanner, reproduction photography, screen grab). While some of the libraries themselves are not open to the public, this exhibition in book form offers glimpses into these cumulative structureshowever, again, only from within the tension of the private.

COMMONPLACE BOOKS

GRR.AAAAARG.ORG

http://grr.aaaaarg.org/txt/collection/detail.php?id=52333d4d307888cb75000006

Partials that can circulate

Sean dockray, Founder of aaarg.org interviewed by charles stankievech

a creative ction that worked in the world, in unpredictable ways experimenting with other forms of living and making things. This research ran in parallel to some infrastructures for groups that I built (a software implementation of anarchist consensus decision-making for non-local, non-synchronous meetings; collaborative writing and drawing tools; some publication platforms; and later things like a library and a school). In this way, I dont think Id separate the formal experiment from the practical infrastructure. CS: At the present, how many documents are served by the Arg.org community? SD: Cant say for sure. After some legal problems a couple of years ago, the site went down, but the library quickly appeared again on another server. I am happy that happened because people put a lot of time and labor into creating that collection and it would be horrible if it were annihilated by lawyers and accountants. But I dont run the site now. And I dont need to, since there are many people who are invested in the sustainability of the library and community. CS: The popularity and the geographic diversity of the users is immense at this point and only going to continue to grow. In what direction do you see Arg.org moving in? SD: Well, the obvious thing would be that it becomes quasiinstitutional, part of the fabric of how things workand that this has happened over the past decade, during which time so much has changed in publishing and education due to the internet, and the internets role in extending the prot imperative to these areas. So this mutual evolution sets up entirely new questions and contradictions for the library (I should note that, for me, library is composed of collection, community and technical infrastructure). And as youve said, the geographic diversity has grown and will continue to grow. On the one hand, arg has extended access to the global South, but also to those in the US who are outside of institutions and paywalls; on the other hand, what happens to those forms of writing, knowledge and theory that is already existing in these situations? Does it become a part of the library and discourse or does aarg simply export the Western canon, overwriting these forms in the process? How the library deals with language, translation, and how it relates to social movements are all part of these questions.

CS: I think one could compare Arg.org with more legal repositories like the Library of Congress, Archive.org or Google Books, but also more independent gestures like the hacking of Aaron Schwartz. From another perspective, one could say, parallel to the history of Arg.org there are the lesharing platforms and protocols like Napster, thepiratebay, megashare, etc., as well as the history of information leaking by whistleblowers such as Wikileaks, Manning, Snowden, etc. Do you see Arg.org connected to either of these types of phenomena? SD: On the one hand, yes, as long as I have been using the internet Ive been excited about these things because they seemed to be making the promise of the internet real, so there is a connection. I can still remember seeing UbuWeb for the rst time, or texts.com. But aarg was not a political statement at the beginning, or a performance of an ideological position, the same way these other things were. That said, each example youve mentioned has in its own way only further demonstrated how destructive and unacceptable private property is, especially in matters of knowledge. I think each instance you have mentioned takes some kind of initiative about what is possible to do within the context of digital networksinitiatives in the spirit of the Library of Alexandria or HG Wellss World Brainand each has a messy confrontation with legality, often changing those very legal structures in the process. In other words, I wouldnt divide them into two phenomena, but rather see them taking many dierent positions across a common eld. But to respond more specically: the Library of Congress, Archive. org, and Google Books each aspire to a kind of completion or totality, which is totally foreign to aarg. The same can be said for Napster, the megas, and The Pirate Bay. And while Wikileaks is involved in a redistribution of knowledge, it is in the service of revelation, of spreading the truth about power, a power that comes in part from keeping those truths secret. aaarg doesnt reveal anything, even though it might undermine a certain form of power through a similar distributive process. The deepest sympathies are probably with Aaron Swartz, whose attention to knowledge and access to resources was combined with a keen sense of global justice. CS: I originally felt while studying in the 1990s, research was changing with the power of search engines available at the time within word processors. One was no longer required to carefully catalogue notes on index cards but could collect all of the quotes and notes in one meta-document and internally search it. Over a decade later, operating systems have built-in search engines

15 September 2013 and ongoing

EX LIBRIS departs from investigating the inside of the book as a potential curatorial space. Initiated in six specic libraries, EX LIBRIS comprises a series of book displays developed within these collections, each of which creates a separate constellation of meanings through the careful organization of selected books. Situated between the exhibition and the editorial process, and using the library both as a resource for curatorial connections from book to book and as a direct platform, EX LIBRIS expands the curator Anna-Sophie Springers original research interest in the book-as-exhibition to include the relationship between the book and its context. If the book traditionally is seen as the strategy for private consumption and research, and the gallery as the space for public exhibition and performance, the libraryas the public place of readingthus becomes the hybrid site for performing the book. The selected libraries range from personal and nonaccessible libraries such as those of artist Nina Canell and book designer Robin Watkins, a private art collector, through the bookshop of gallerists/ publishers Barbara Wien and Wilma Lukatsch to the state-funded, public collections of the Academy of Visual Arts, Leipzig and the Art Library of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Pointing to contemporary transformations in print culture, the digital pirate archive GRR.AAAAARG.ORG is also probed, engaging the particularity of seeking unrestricted accessibility through private efforts. Together, these collections reect an exemplary publicprivate spectrum.

A PDF has been created from excerpted and copied passages of thematically relevant publications available in digital form in the Arg library. It has been uploaded back onto the platform and a link will appear in the New Texts section on http://grr.aaaaarg.org making it available to all network users.

At that same time, I had been doing research into autonomous art and architecture groups, mainly through surveys and interviews, to understand how they materially survived, how they made decisions, how they distributed power, and how they safeguarded their autonomy. It appeared to me that although each group made projects, the group itself was the most interesting projectit was

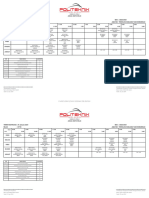

Exlibris-ARG-A3-layoutDemo-Tab-7Col-Front-ENG.indd 1

2013-09-15 3:13 AM

commonplace books

Dating back to antiquity and with particular popularity in the Renaissance period, commonplace books are a type of scholarly notebook containing a collection of excerpted and copied passages that a person compiled and stored for future purposes such as reference and quotation. How to actually keep and organize a commonplace book was a small science in itself. John Lockes text A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books (1706) suggested some techniquesone of which is a system of classifying and coding entries into a growing subject index, ones personal potential encyclopedia. While physical notebooks remain a treasure to keep and even if we do not yet live in a truly paperless age, our commonplace of today is that we access and store a huge amount of information digitally. By engaging an online pirate library, specically the Arg library, Commonplace Books seeks to address shifts in how we approach notions such as the common or the public more openly and actively than ever.

Charles Stankievech: Lets start at an imagined beginning. Why did you start Arg.org: was it a solitary venture in the form of an experiment or connected to something else which required the infrastructure? Sean Dockray: An imagined beginning! I like that, because there is no beginning (like there will never be an end) but rather a coherent form that emerges for a period of time, out of many people, ideas, and circumstances, before it disperses again into bits and memory and new forms. I can say that it wasnt an experiment in making information free in the abstract. Rather I was involved in several small collaborations, private remote correspondences, and semipublic debates, all of which were directly or indirectly trying to come to an understanding of, or invent a vocabulary for the contemporary political and economic realities of the time, around 2003. George Bush was the President of the US, which was itself expanding its permanent war on terror, and there seemed to be no ght or theory coming from the left. In that context, aaarg was just an infrastructure for these fragmented discussions and projects to share theoretical resources, reading material.

IMPRESSUM

and Google is synonymous with the web, making the collection and nding of information take a methodological quantum leap. Of course, academic search engines pregured such a phenomenon for the researcher, but the ease and ubiquity of the search engine seems to change the way people research and possibly connect and present information. Do you think there is a fundamental shift occurring with digital media and repositories of information when it comes to learning and writing? SD: Although there have been fundamental changes in the archives and especially the tools with which we can browse, sort, and search these archives, I am not sure that there has been a corresponding shift in our sensibilities and in our reading and writing practices. Across the computers that maintain the search indexes you are talking about, all of the texts are decomposed and recombined with one another into structures completely alien to their writing. Only when re-presented to us in search results do they return to their familiar form of an authored volume. Our solitary reading and writing practices havent made the same radical jump and it might be interesting to see ways in which readership and authorship could be decomposed and collectivized, not just as wordplay but embodied formal experiments. CS: Perhaps something like EX LIBRIS plays exactly with this formal experiment you are referring to, for it seems like something regarding the project has changed with the shift to the digital archive. For example, the history of the Cut-Up technique I feel attempts to deal with an explosion of media information, by turning a random/intuitive assemblage of information into a statement of meaning. Do you not feel that something like Aaargs scanned documents pushes research and writing in this direction? You have mentioned insightfully elsewhere both the prevalence of the cut & paste options today as well as the scanned page existing as an excerpt or a subjective partial. A library of partials I imagine would shape research and writing uniquely, and I do feel though that something like AAaarg creates the ability to collect information across a broad landscape of data and rapidly juxtapose these texts, which results in something dierent than the more traditional linear reading. SD: I am curious to nd out what eect the library has had on peoples writing. For me, the partials are important not because they can be easily recombinedthink of a musical sample library, for instancebut because those subjective partials are so invested with somebodys attention, an attention thats only magnied by the work of making notes and scanning. Broken out of their contexts (book, discipline, copyright regime, etc.) I think the partials can circulate

A curatorial-editorial experiment by Anna-Sophie Springer Miniature publication produced for the third iteration of a six-part project called EX LIBRIS: Commonplace Books GRR.AAAAARG.ORG 15 September 2013 and ongoing

to new readers and be activated in new ways, yes, often in relation to texts to which they may not have typically been exposed. You nd that the site is used in many reading groups outside of ocial academic classes and institutions, or for self-education, and the purpose it seems to me is less about mastery of a discipline than it is about identifying the tools to make meaning out of where we nd ourselves, and learning to use them. But back to writing, I think that AAaarg could go much further: for example, the discussion around a text could happen within the text; readings could layer on top of readings such that when you read a text you read its past readings as well; you might read one text in the library within the margin of another text, and so on. I also have thought recently that video lectures should be considered texts, especially since most of the time the person is reading a text which may or may not ever be published in written form. These videos travel in parallel to written texts now. How do they live in the library in a meaningful way without being marginalized into the video library? How do these videos become incorporated into new writing projects? CS: Would you at least agree research has reached a terminal velocity in the indexeither with every word in a text searchable in formats like epubs or OCR pdfs, or simply the democratic access to meta-indexes, and that this possibly has in turn an inuence in research and writing? SD: Absolutely, I agree with you that the full-text indexing of so many books is remarkable and qualitatively dierent from historical cataloguing projects. And as we know, the search algorithms are still under active developmentso perhaps we havent reached the limits youre implying, but we will nd new peaks revealing themselves to us from this new perspective. But reading and writing do adapt to the particularities of the searchable libraryin fact, we could say that searching itself becomes a mode of reading (similar to how skimming or reading out loud in a group are each dierent from a close reading). When we search we read from the middle outwards, from the relevant passage into the rest of the text, as far as we choose to go. Its just one way that these dierent modes transition into one another. Although I think there is a lot of possibility in these indexes and in libraries that try and explore the creative potential of the indexed archiveexperimenting with dierent searching and ltering algorithms, or dierent compositional tools beyond the word processorits really only possible if the indexes and the archives

that they index are actually available. This is one of the damaging inuences of copyright and rent-seeking on knowledge. There are many possible archives that are never built, or actual common archives that have been run underground or destroyed such that there isnt the time or space to develop these projects. The platforms are often too precarious, they are under attack; and the corporate versions under-develop the resources in order to manage access and establish payment rituals, which in turn retards research and writing. This is why I think that radical software development and a conception of the digital commons shouldnt be separated from one another. This interview took place via email in July / August 2013.

BIBLIOGRAphy

FHistory, (New York and London: Routledge, 2005), PDF, 1; 88.

inkelstein, David and Alistair McCleery, An Introduction to Book

Nodier, Charles, Story of the Bibliomaniac (Cleveland: Rowfantia, 1900), PDF, 2.

A154; PDF, 20.

mazing Archigram: A Supplement, Perspecta, Vol. 11, 1967, 131

Foster, Hal, An Archival Impulse, October 110, Fall 2004, 322; PDF, 9. Foucault, Michel, What is an Author? (1969), James L. Marsh, John D. Caputo, and Merold Westphal (eds.), Modernity and its Discontents (New York: Fordham University Press, 1992), 299314; PDF, 16. Friedberg, Anne, The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2006), PDF, 16. Friedman, Ken, Owen Smith and Lauren Sawchyn (eds.), The Fluxus Performance Workbook (Performance Research e-pub, 2002); PDF, 47.

Pand Bonnie G. Smith, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1993), PDF, 35. 2011), PDF, 1; 44; 45.

roudhon, Pierre-Joseph, What is Property?, ed. by Donald R. Kelley

Antfarm, Inatocookbook, second edition, San Francisco 1973; PDF, 5.

B5 February 2010.

alkoski, Katherine, Cease and Desist, Columbia University Press,

R(Urbana, Chicago and Springeld: University of Illinois Press,

amsay, Stephen, Reading Machines: Toward an Algorithmic Criticism Raven, James (ed.), Lost Libraries: The Destruction of Great Book Collections Since Antiquity (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), PDF, 6; 18; 24. Ronney, Ellen, A Semiprivate Room, dierences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, Vol. 13, No. 1, Spring 2002, 128156; PDF, 14.

Barthes, Roland, La mort de lauteur (1968), ibid., Essais critiques, IV: Le bruissement de la langue (Paris: Seuil, 1984), 6167; PDF, 1. Boon, Marcus, In Praise of Copying (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010), PDF, 4. Buchloh, Benjamin, Three Conversations in 1985: Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, Robert Morris, October 70, Fall 1994, 3354; PDF, 48. Burroughs, Willam S. and Brion Gysin, The Third Mind (New York: The Viking Press, 1978); PDF, 20. Butler, Cornelia and others (eds.), From Conceptualism to Feminism: Lucy Lippards Number Shows 196974 (London: Afterall, 2012), PDF, 54; 70; 87.

GBedford Press, 2010), PDF, 3; 19. all, Gary, Digitize This Book! The Politics of New Media, or Why We HNeed Open Access Now (Minneapolis and London: University of

rigely, Joseph, Exhibition Prosthetics, ed. by Zak Kyes (London: Minnesota Press, 2008), PDF, 7; 28.

SDolphin Enterprise, Inc., 1982), PDF, 95.

croggy, David (ed.), Blade Runner Sketchbook (San Diego: Blue

Design: Charles Stankievech With special thanks to Prof. Dr. Beatrice von Bismarck, Dr. Joachim Brand, Nina Canell, Claudia Darmer, Sean Dockray, Judith Krakowski, Dr. Michael Lailach, Wilma Lukatsch, Dr. Benjamin Meyer-Krahmer, Christian Philipp Mller, Leah Whitman-Salkin, Willy + Monika Springer, Charles Stankievech, ve K. Tremblay, Robin Watkins, Prof. Thomas Weski, Barbara Wien, Edda Wilde and all the sta of the Leipzig Academy Library. Published by: K. Verlag | Press Karl-Marx-Platz 3 D-12043, Berlin www.k-verlag.com ISBN:978-0-9877949-6-3

JPDF, 3; 51; 204; 205.

ones, Owen, The Grammar of Ornament (London: Day and Son, 1856), ocke, John, A New Method of Making Common-Place Books (London: J.

Sebald, W.G., The Rings of Saturn (London: Vintage Books, 2002), epub, 369.7. Siegelaub, Seth and John Wendler (eds.), The Xerox Book (New York, 1968), PDF, 9; 14; 16; 23. Simanowski, Roberto, Digital Art and Meaning: Reading Kinetic Poetry, Text Machines, Mapping Art, and Interactive Installations, (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), PDF, 54. Staniszewski, Mary Anne, The Power of Display: A History of Exhibition Installations at the Museum of Modern Art (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1998), PDF, 42. Starr, Kevin, Great cities need great libraries, The Press Enterprise, 12 March 1995, A-13. Szirmai, J.A., The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding (Brookeld, Vt.: Ashgate, 1999), PDF, 12; 13; 77; 124; 147; 190; 231.

CLanguage, 4.1, January 1970.

rouwel, Wim, Type Design for the Computer Age (1969), Visible

LGreenwood, 1706), front + back cover; title page.

Venice (Tempe, Az: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance D Studies, 1999), PDF, 32. avies, Martin, Aldus Manutius: Printer and Publisher of Renaissance Derrida, Jacques, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), PDF, 58. Didi-Huberman, Georges, Confronting Images: Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art (University Park, Pa: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005), PDF, 3; 4. Dworkin, Craig and Kenneth Goldsmith, Against Expression: An Anthology if Conceptual Writing (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2011), PDF, 1.

Ludovico, Alessandro, Post-Digital Printing: The Mutation of Publishing Since 1894 (Eindhoven: Onomatopee, 2012), PDF, 161163.

MDigital Age (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2009), PDF,

ayer-Schnberger, Viktor, Delete: The Virtue of Forgetting in the 2; 143. McMillan, John, Smoking Typewriters: The Sixties Underground Press and the Rise of Alternative Media in America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), PDF, 134; 139.

NUniversity Press, 2008), PDF, 3642.

etanel Weinstock, Neil, Copyrights Paradox (Oxford: Oxford

W11 December 2009.

ilson, Rowan, ATTENTION AAAARG.ORG ADMINISTRATOR,

Exlibris-ARG-A3-layoutDemo-Tab-7Col-Front-ENG.indd 2

2013-09-15 3:13 AM

You might also like

- Think, Feel, Touch, Do: Zines in The Archive of The "Living" DeadDocument51 pagesThink, Feel, Touch, Do: Zines in The Archive of The "Living" DeadHeath Ray DavisNo ratings yet

- Unfeigned.'": On Listening To Lectures, IDocument8 pagesUnfeigned.'": On Listening To Lectures, Ipeteatkinson@gmail.comNo ratings yet

- Phenomenal Reading: Essays on Modern and Contemporary PoeticsFrom EverandPhenomenal Reading: Essays on Modern and Contemporary PoeticsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Under the Covers and between the Sheets: Facts and Trivia about the World's Greatest BooksFrom EverandUnder the Covers and between the Sheets: Facts and Trivia about the World's Greatest BooksRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (19)

- Homemade Biography: How to Collect, Record, and Tell the Life Story of Someone You LoveFrom EverandHomemade Biography: How to Collect, Record, and Tell the Life Story of Someone You LoveRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1)

- Reading and Not Reading The Faerie Queene: Spenser and the Making of Literary CriticismFrom EverandReading and Not Reading The Faerie Queene: Spenser and the Making of Literary CriticismNo ratings yet

- The Improbability of Othello: Rhetorical Anthropology and Shakespearean SelfhoodFrom EverandThe Improbability of Othello: Rhetorical Anthropology and Shakespearean SelfhoodNo ratings yet

- A Short History of English Printing, 1476-1898From EverandA Short History of English Printing, 1476-1898Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Behind the Shadows of Romeo : A William Shakespeare Biography Book for Kids | Children's Biography BooksFrom EverandBehind the Shadows of Romeo : A William Shakespeare Biography Book for Kids | Children's Biography BooksNo ratings yet

- The Matter of Capital: Poetry and Crisis in the American CenturyFrom EverandThe Matter of Capital: Poetry and Crisis in the American CenturyNo ratings yet

- Coyotes Go to Heaven: A Biographical Account of F. Robert Henderson and Karen Lee Henderson 1933 – 2016From EverandCoyotes Go to Heaven: A Biographical Account of F. Robert Henderson and Karen Lee Henderson 1933 – 2016No ratings yet

- 30 Poems in 30 Days: Poetry Prompts Inspired by Trio House Press PoetsFrom Everand30 Poems in 30 Days: Poetry Prompts Inspired by Trio House Press PoetsKris BigalkNo ratings yet

- Dear Poet: Notes to a Young Writer: A Poetic Journey into the Creative Process for Readers, Writers, Artists, & DreamersFrom EverandDear Poet: Notes to a Young Writer: A Poetic Journey into the Creative Process for Readers, Writers, Artists, & DreamersRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Spirits of Birds, Bears, Butterflies and All Those Other Wild CreaturesFrom EverandThe Spirits of Birds, Bears, Butterflies and All Those Other Wild CreaturesRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Narrative and Its Nonevents: The Unwritten Plots That Shaped Victorian RealismFrom EverandNarrative and Its Nonevents: The Unwritten Plots That Shaped Victorian RealismNo ratings yet

- The Dead Queen of Bohemia: New & Collected PoemsFrom EverandThe Dead Queen of Bohemia: New & Collected PoemsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Multiple Choice Quiz Chapter 5Document4 pagesMultiple Choice Quiz Chapter 5gottwins05No ratings yet

- MAPEH - 10 Semi Final EXAMDocument2 pagesMAPEH - 10 Semi Final EXAMGlendle OtiongNo ratings yet

- Example 1: Analytical Exposition TextDocument1 pageExample 1: Analytical Exposition Textlenni marianaNo ratings yet

- Dangerous Prohibited Goods Packaging Post GuideDocument66 pagesDangerous Prohibited Goods Packaging Post Guidetonyd3No ratings yet

- Manual Placa Mãe X10SLL-F Super Micro PDFDocument111 pagesManual Placa Mãe X10SLL-F Super Micro PDFMarceloNo ratings yet

- Review Test: Unit 1: Focus On Grammar 5E Level 4Document10 pagesReview Test: Unit 1: Focus On Grammar 5E Level 4Alina LiakhovychNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document43 pagesChapter 1arun neupaneNo ratings yet

- Bill FileDocument4 pagesBill FilericardoNo ratings yet

- Leijiverse Integrated Timeline - Harlock Galaxy Express Star Blazers YamatoDocument149 pagesLeijiverse Integrated Timeline - Harlock Galaxy Express Star Blazers Yamatokcykim4100% (3)

- Swconfig System BasicsDocument484 pagesSwconfig System BasicsLeonardo HutapeaNo ratings yet

- GSM500BT Bluetooth Barcode Scanner User Manual GENERALSCAN ELECTRONICS LIMITEDDocument14 pagesGSM500BT Bluetooth Barcode Scanner User Manual GENERALSCAN ELECTRONICS LIMITEDipinpersib ipinNo ratings yet

- Corona vs. United Harbor Pilots Association of The Phils.Document10 pagesCorona vs. United Harbor Pilots Association of The Phils.Angelie MercadoNo ratings yet

- NC 700 Errores Cambio SecuencialDocument112 pagesNC 700 Errores Cambio SecuencialMotos AlfaNo ratings yet

- CS310 Dec 2021 - KCCDocument18 pagesCS310 Dec 2021 - KCCLAWRENCE ADU K. DANSONo ratings yet

- Manual de Operación Terrometro de GanchoDocument19 pagesManual de Operación Terrometro de GanchoIsrael SanchezNo ratings yet

- 9bWJ4riXFBGGECh12 AutocorrelationDocument17 pages9bWJ4riXFBGGECh12 AutocorrelationRohan Deepika RawalNo ratings yet

- Reactivation+KYC 230328 184201Document4 pagesReactivation+KYC 230328 184201Vivek NesaNo ratings yet

- Columna de Concreto 1 DanielDocument3 pagesColumna de Concreto 1 Danielpradeepjoshi007No ratings yet

- Nervous System IIDocument33 pagesNervous System IIGeorgette TouzetNo ratings yet

- 3 HACCP Overview Training DemoDocument17 pages3 HACCP Overview Training Demoammy_75No ratings yet

- Advances in Energy Research, Vol. 1: Suneet Singh Venkatasailanathan Ramadesigan EditorsDocument734 pagesAdvances in Energy Research, Vol. 1: Suneet Singh Venkatasailanathan Ramadesigan EditorsVishnuShantanNo ratings yet

- BJT SummaryDocument4 pagesBJT SummaryPatricia Rossellinni GuintoNo ratings yet

- 1998 USC Trojans Baseball Team - WikipediaDocument7 pages1998 USC Trojans Baseball Team - WikipediaPauloHenriqueRibeiro100% (1)

- Pre Basic and Basic TestDocument9 pagesPre Basic and Basic TestkacelyNo ratings yet

- Breast UltrasoundDocument57 pagesBreast UltrasoundYoungFanjiensNo ratings yet

- Chapter6-Sedimentary RocksDocument6 pagesChapter6-Sedimentary Rockssanaiikhan2020No ratings yet

- Oracle9i Database - Advanced Backup and Recovery Using RMAN - Student GuideDocument328 pagesOracle9i Database - Advanced Backup and Recovery Using RMAN - Student Guideacsabo_14521769No ratings yet

- Basic Marketing Research 4th Edition Ebook PDFDocument61 pagesBasic Marketing Research 4th Edition Ebook PDFrita.ayers590100% (44)

- Dell OptiPlex 3020 Owners Manual MT PDFDocument63 pagesDell OptiPlex 3020 Owners Manual MT PDFGelu UrdaNo ratings yet

- JTMK JW Kelas Kuatkuasa 29jan2024Document20 pagesJTMK JW Kelas Kuatkuasa 29jan2024KHUESHALL A/L SRI SHANKAR LINGAMNo ratings yet