Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dissertation Xinxin Wu 2006dissertation - Xinxin - Wu

Uploaded by

Vu Thuy DungOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dissertation Xinxin Wu 2006dissertation - Xinxin - Wu

Uploaded by

Vu Thuy DungCopyright:

Available Formats

An Empirical Test of CAPM: Evidence

from Shanghai Stock Exchange 2001-2005

by

Xinxin Wu

2006

A Dissertation presented in part consideration Ior the

degree oI MA Investment and Finance

2

ABSTRACT

As a Iinancial theory, the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) has dominated the

academic literature and inIluenced greatly the Iield oI Iinance and business in practice

over Iour decades. This dissertation examines the validity oI the CAPM in the Shanghai

Stock Exchange (SSE) which is one oI the two stock exchanges in the mainland China

Ior the period Jan 2001Dec 2005. Employing the approach proposed by Fama and

MacBeth (1973) with modiIications suggested by Pettengill et al. (1995), I reach a

conclusion that is inconsistent with Fama and MacBeth (1973)`s Iinding as the

unconditional CAPM is not valid in the SSE, while conditional CAPM is inapplicable

either since there only exist weak insigniIicant beta-return relationship. Using beta as the

only proxy Ior risk is questionable. In addition, aIter comparing the empirical SML with

the theoretical SML under the conditional CAPM, the slope oI the relationship between

realized return and beta is less than that oI the relationship between expected return and

beta predicted by the CAPM with the SML is steeper positively in up market and Ilatter

negatively in down market. In general, the CAPM does not hold in the Chinese stock

market.

3

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page

ABSTRACT..................................................................................................................2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................5

LIST OF TABLES........................................................................................................6

LIST OF FIGURES .....................................................................................................7

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................8

1.1 Research Objectives.........................................................................................8

1.2 Research Methodology ....................................................................................9

1.3 Dissertation Structure.....................................................................................10

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW...............................................................12

Introduction..........................................................................................................12

2.1 The CAPM Theoretical Background .............................................................12

2.1.1 The Development oI the CAPM Equation............................................................12

2.1.2 The Security Market Line....................................................................................15

2.1.3 The CAPM Assumptions .....................................................................................16

2.2 Prior Empirical Surveys.................................................................................18

2.2.1 Early Empirical Evidences Irom the US Markets ................................................19

2.2.2 Empirical Evidences ThereaIter ..........................................................................20

2.2.2-1 Positive Evidence aIter 1970s in the US Markets .....................................21

2.2.2-2 Debates against the CAPM......................................................................21

2.2.2-3 DeIence oI the CAPM .............................................................................26

2.2.2-4 Evidences Irom Other Developed Markets...............................................31

2.2.2-5 Evidences Irom Emerging Markets ..........................................................36

Conclusion ...........................................................................................................40

CHAPTER 3 THE CHINESE STOCK MARKET AND ITS MARKET

INSTITUTIONS.........................................................................................................41

Introduction..........................................................................................................41

3.1 The Chinese Stock Markets ...........................................................................41

3.2 Market Institutions.........................................................................................42

3.1.1 A and B Shares....................................................................................................43

3.1.2 Listing Procedure and Market Exit Mechanism....................................................45

3.1.3 Typical Characteristics oI Chinese Stock Markets ................................................47

3.3 The Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) ............................................................49

Conclusion ...........................................................................................................51

CHAPTER 4 EMPIRICAL TEST OF THE CAPM............................................53

Introduction..........................................................................................................53

4

4.1 Data and Methodology...................................................................................54

4.1.1 Data Collection ...................................................................................................54

4.1.2 Methodology.......................................................................................................56

4.2 Empirical Test Results and Discussions.........................................................63

4.2.1 General Findings .................................................................................................63

4.2.2 Regression Analysis ............................................................................................69

4.2.2.1 The Unconditional Relationship................................................................70

4.2.2.2 The Conditional Relationship....................................................................74

4.2.3 Security Market Line (SML) Analysis .................................................................79

Conclusion ...........................................................................................................84

CHAPTER 5 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION................................................86

BIBLIOGRAPHY......................................................................................................90

APPENDIX 1: Data oI 80 Listed Securities and Market Index ...............................97

APPENDIX 2: The Unconditional Regression Test Results ....................................99

APPENDIX 3: The Conditional Regression Test Results ...................................... 102

APPENDIX 4: The Theoretical Test Results Ior the Conditional Relationship

between Expected Return and Beta ........................................................................... 105

5

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to give my gratitude to my supervisor Dr Ghulam Sorwar, Ior his guidance,

support and encouragement throughout the process oI this dissertation.

Further, I would like to express my appreciation to my parents and Iriends, with their

consistent love and support; I Iinally Iinish my one-year MA study.

6

LIST OF TABLES

Page

Table 3.1 Tradable A-shares in both SSE and SZSE 44

Table 3.2 The SSE Trading Summary Ior the Year 2005 50

Table 4.1 PortIoliosTotal Sample Period 66

Table 4.2 Unconditional Test ResultsStocks 70

Table 4.3 Unconditional Test ResultsPortIolios 72

Table 4.4 Conditional Test ResultsPortIolios 75

7

LIST OF FIGURES

Page

Figure 1.1 Security Market Line 15

Figure 3.1 Historical Trend oI the SSE Index 51

Figure 3.2 Trend oI the Movement oI the SSE Index 51

Figure 4.1 Realized Return and Stock STD (Total Period) 64

Figure 4.2 Realized Return and Stock Beta (Total Period) 64

Figure 4.3 Realized Return and Stock Beta (1

st

Sub-period) 65

Figure 4.4 Realized Return and Stock Beta (2

nd

Sub-period) 65

Figure 4.5 Realized Return and PortIolio STD (Total Period) 66

Figure 4.6 Realized Return and PortIolio Beta (Total Period) 67

Figure 4.7 Realized Return and PortIolio Beta (1

st

Sub-period) 67

Figure 4.8 Realized Return and PortIolio Beta (2

nd

Sub-period) 68

Figure 4.9 Realized Return and PortIolio Beta in Up and Down Market 76

Figure 4.10 Expected Return and PortIolio Beta in Up Market 80

Figure 4.11 Expected Return and PortIolio Beta in Down Market 80

Figure 4.12 Theoretical SML and Empirical SML in Up Market 82

Figure 4.13 Theoretical SML and Empirical SML in Down Market 82

8

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Research Objectives

The Chinese economic reIorm and open door policies implemented since 1978 has given

rise to the establishment oI the Chinese Stock Market in the early 1990s, which then is

expanding dramatically year by year. As one oI the most important emerging markets

around the world, the Chinese stock market has attracted many researchers Irom diIIerent

perspectives with diIIerent approaches.

The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) developed by Sharp (1964), Linter (1965) and

Black (1972) has been one oI the dominant capital asset equilibrium models in Iinance

theory. The CAPM Iocuses on the relationship between systematic risk and expected

return oI assets with the central tenet that systematic risk as measured by beta is the only

Iactor that accounts Ior return required by completely diversiIied investors. In addition, as

Peasnell (1986) indicated, the CAPM has been utilized in great variety oI ways Ior

diIIerent purposes.

Nevertheless, in general, empirical tests Ior the CAPM model has mainly emphasised on

three implications: the intercept is equal to the risk-Iree rate oI return; there exists a linear

relationship between risk and return; and the market risk premium is positive.

This dissertation will carry out an empirical test oI the CAPM in Chinese stock market,

aiming to provide some contributions regarding to the relevant literature since most

9

CAPM researches have been Iocused on the US or other developed markets in Europe.

International markets especially the emerging markets in Asia have received considerably

less attention. In particular, there are very limited literatures exist in respect to the

applicability oI the CAPM in China stock markets.

However, due to time constraint, this study puts attention to research one oI the two stock

exchanges in the Mainland Chinathe Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) on the basis oI

relevant theories and academic Iindings. It examines beta-return relationship in the SSE

in order to assess the applicability oI the CAPM in Chinese stock market, while the

Security Market Line (SML) oI the SSE can be drawn and considered thereaIter.

1.2 Research Methodology

Data collection and calculation is the most important part oI this study. In this dissertation,

Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) will be used as the research scope due to the reason that

it is the largest and representative stock exchange in the mainland China. Its research will

be helpIul to give the indication oI the applicability oI CAPM in Chinese stock market.

The data used in the dissertation consists oI the randomly chosen closing stock prices and

the SSE Index value based on 5 years/60 months Irom January 2001 to December 2005.

All data can be taken Irom the Stockstar Exchange SoItware and the database oI the SSE.

In general, the methodology used in this dissertation is a two-step regression model that

is Irom Fama and MacBeth (1973), with modiIications suggested by Pettengill et al.

(1995). The Iirst step involves using a regression model

it i t t it

e R + + = |

1 0

to examine

10

the unconditional approach oI the beta-return relationship. The test oI this model is based

on the mean oI the coeIIicients oI the monthly regressions. II the realized return is more

than the risk-Iree interest rate with a signiIicant t-statistic, a positive unconditional

relationship between beta and return is supported, which provides important implications

concerning empirical test Ior a systematic relationship between beta and return.

The second step involves using the cross-sectional regression model

it i t i t t it

e D D R + + + = | | ) 1 (

2 1 0

to examine the conditional relationship between

beta and return, where there should be a positive beta-return relationship when the excess

market return is positive and a negative relationship when the excess market return is

negative. The above model can be tested by the standard t-statistic using hypotheses test.

II conditional CAPM is valid, a systematic conditional relationship between beta and

realized return will be supported and the null hypothesis should be rejected. AIter

evaluating the results Irom both unconditional and conditional analysis, the relationship

between risk as measured by beta and return will be shown by the SML.

1.3 Dissertation Structure

This paper is organized as Iollows:

Chapter 2 covers the literature review oI this study so that to establish the academic

Ioundation Ior the empirical test. It includes empirical evidences in respect to the CAPM

Irom both developed markets and emerging markets. In particular, debates against the

CAPM, deIence Ior the CAPM will be discussed.

11

Chapter 3 introduces and considers the Chinese stock market and its market institutions.

The purpose is to provide background knowledge in order to help to understand the

diIIerences between the china stock market and other developed markets.

Chapter 4 includes the empirical test oI the CAPM. Data collection, methodology and

results Irom both general Iindings and regression analysis are described and examined.

Finally, Chapter 5 provides the summary and conclusions Ior this study. Limitations oI

this dissertation, especially Ior the empirical test results will also be considered in this

chapter.

12

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Introduction

In respect to the literatures regarding to empirical test oI the CAPM, many researchers

have already engaged the relevant study in Iinancial markets in diIIerent countries. In this

chapter, aIter summarizing the CAPM theoretical background, past studies will be

reviewed by dividing them into three sections: early empirical evidence Irom the US

markets, empirical evidence Irom both the US and other developed markets thereaIter,

and Iinally, empirical results Irom emerging markets, especially the Asian markets.

2.1 The CAPM Theoretical Background

As a Iinancial theory, the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) has dominated the

academic literature and greatly inIluenced the Iield oI Iinance and business in practice

over Iour decades. The attraction oI the CAPM is not only accounted Ior its powerIul and

intuitive predictions about how to measure systematic risk and the relationship between

expected return and risk, but also accounted Ior its simplicity and convenience in use.

2.1.1 The Development of the CAPM Equation

Prior to the development oI the CAPM, in the 1950s, Harry Markowitz`s (1952)

diversiIication and modern portIolio theory argues that aIter considering the co-

movements oI each stock with all other stocks, a better portIolio could be constructed that

had the same expected return but less risk than a portIolio being constructed by ignoring

the interactions between stocks. James Tobin (1958) Iurther developed conditions under

13

which Markowitz`s mean-variance theory could be optimal. Tobins` separation theorem

shows that in order to be optimal, each investor should only hold eIIicient risky portIolio

and the risk-Iree asset. However, the theory oI Markowitz and Tobin could not be

implemented at that time because it requires the inversion oI the covariance matrix oI

returns among all securities under consideration, which was an impossible task Ior that

period due to the limited computing power. (Das et al. 2002)

In the 1960s, William Sharp (1964) developed a pioneering achieving index model-the

Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) which eIIectively solved this practical problem.

Given the condition that all investors Iollow Markowitz`s mean-variance approach, the

expected return on a security will be positively and linearly related to the class oI its

market beta, where the systematic risk should be directly related to the expected return

under the situation oI market equilibrium. That is, the higher (lower) a security`s beta the

higher (lower) its expected return. Moreover, Mossin (1966) conIirmed the existing oI the

security market line and emphasized the importance oI market equilibrium. Lintner (1965)

and Black (1972) observed that the market portIolio oI risky securities is mean variance

eIIicient, which implies that the market beta should be the only proxy Ior the security`s

risk. Further, Black (1972) developed a more general version oI the equilibrium expect

return-beta relationship as he releases the restrictions on risk-Iree investments, where the

risk-Iree asset is replaced by a portIolio that has the minimum variance oI all portIolios

uncorrelated with the market portIolio.

Based on the Iindings oI Sharp (1964) and Lintner (1965), Black (1972) derived the

14

capital asset pricing model (CAPM) under conditions oI market equilibrium as Iollows,

| ) ( | ) (

f m i f i

R R E R R E + = | (1)

Where ) (

i

R E - the expected return on asset i Ior the period is the return on the risk Iree

asset (

f

R ), plus the risk premium on the market | ) ( |

f m

R R E , times the risk on the

asset relative to the market (

i

| ).

i

| is the sensitivity oI asset i to the market movements

and the slope oI the regression line between

i

R and

m

R , in which could be deIined as the

ratio oI the covariance (or co-movement) oI returns on asset i and the market portIolio m

to the variance oI returns oI the market portIolio.

2

,

) (

m

m i

i

R R Cov

o

| = (2)

The above expected return and beta relationship is the most Iamiliar expression oI the

CAPM, and, in addition, because oI the joint eIIorts oI three economists (Sharp, Lintner

and Black); the CAPM equation is also called the Sharp-Lintner-Black (SLB) model.

Moreover, in respect to the deIinition oI beta, Brealey and Myers (1999) made a

considerable and composite description by classiIying the level oI risky investment. The

least risky investment such as bond or treasury bills, have a beta oI zero. The market

portIolio oI common stocks have an average beta oI one as the aggressive stocks have a

beta value more than one and the deIensive stocks have a beta value less than one.

15

2.1.2 The Security Market Line

Using beta as a measure oI systematic risk, the beta-return relationship on an asset can be

represented by the Security Market Line (SML). The CAPM indicated that the expected

risk premium should change sensitively with beta, all investment must plot along the

SML connecting the bond or treasury bills and the market portIolio, and the average

stock returns are positively related to the beta. The SML demonstrates that the expected

return to any risky assets or portIolios is the sum risk premium determined by the value

oI beta and the risk Iree rate.

The Security Market Line (SML) can be expressed as:

Figure 1.1: Security Market Line

According to the mean-variance theory, Richard Roll (1978) indicated that the SML

analysis interprets deviations in expected return Irom the SML above or SML below. All

assets and risky portIolios should lie on the SML ex ante, meanwhile, all oI the ex post

E

x

p

e

c

t

e

d

R

e

t

u

r

n

m

R

f

R

Security Market Line

Systematic Risk (Beta)

16

deviations Irom the SML are caused by statistical estimation errors. The ex ante SML is

based on the ex ante expected return at the beginning oI the year, but the ex post SML is

drawn in accordance with the actual return at the end oI the year.

2.1.3 The CAPM Assumptions

A number oI important and Iundamental assumptions were made Ior the simplicity oI the

CAPM, and guarantee a single optimal risky portIolio and the unique trade-oII between

risk and return Ior all investors, they are:

1. Investors are all risk-averse and rational mean-variance optimisers, which mean they

all use Markowitz portIolio selection model.

2. All investors have identical subjective estimates oI the means, variances, and

covariances oI return among all assets, that is, investors have homogeneous

expectations and perceive identical opportunity sets.

3. All investors can borrow or lend an unlimited amount at a given constant risk-Iree

rate oI interest

f

R .

4. All investors have common investment horizons.

5. All assets are perIectly divisible and priced in a perIectly competitive market.

6. The capital market is perIect, and thereIore, (1) InIormation is costless and

simultaneously available to all investors; (2) There are no transactions costs, no taxes

or any other market Irictions; (3) All investors are price takers, that is, no single

investor can aIIect the security price Irom buying or selling activities.

7. The market is in equilibrium and there is a deIinite number oI assets and their

17

quantities are Iixed within the one period world. That is, the total quantity oI risky

securities that investors want to buy is equal to the total quantity that other investors

want to sell.

However, the above assumptions that underlie the CAPM model are restrictive and

unrealistic, release these assumptions could lead to a diIIerent perspective and result. For

example, release assumption 2 and 6 would result in investors to have heterogeneous

expectation in terms oI their expected return, and hence choose their own eIIicient

Irontier with diIIerent market portIolios because oI inIormation asymmetry or transaction

costs or diIIerent time horizons. Further, iI assumption 3 is violated due to the restriction

oI borrowing, the lending-borrowing line would intercept at diIIerent points on the

eIIicient Irontier. Nevertheless, only when the market is in equilibrium, all risky assets

will be included in the market portIolio, and hence guarantee the mere choice Ior

investors to hold a combination oI risk-Iree assets and market portIolio in accordance

with their utility Iunction.

In reality, investors have their own risk preIerences, and may be risk-loving instead oI

risk-averse. In other words, investors may have a preIerence Ior risk, and may have a

discontinuous utility curve. Moreover, it is impossible Ior investors to have identical

expectations because oI the diIIerent levels oI inIormation, Ior instance, institutional

investors and individual investors. Institutional investors have some degree oI advantage

compared to individual investors as they may have inside inIormation and may have the

power to aIIect share prices. Investors are not likely to use the same lending and

18

borrowing rate as well, because lenders need to make money Irom lending and borrowers

have to pay a deIault premium rate. The investment horizons Ior investors are also

diIIerent as investors may choose their horizons that tailored to their individual needs.

Young couple may preIer risky investment such as stocks and derivatives in order to earn

great excess return to satisIy their huge expenses, whereas retired people may preIer bond

or treasury bills as they have settled well and do not expend a lot. Finally, the capital

market is imperIect. InIormation is not costless and simultaneously available; there are

only limited numbers oI public reports; insider trading exists not only in developing

markets, but also in developed markets; all investors pay taxes and transaction costs Ior

their trading in securities.

However, although these assumptions are strong and unrealistic that deviate Irom the

reality, as Xu (2001 cited in Diacogiannis, 1993, p316) the Iinal test oI a theoretical

model is not how realistically its assumptions reIlect the real world but how well the

model Iits real data.` ThereIore, the validity oI CAPM can only be established through

empirical tests.

2.2 Prior Empirical Surveys

AIter the CAPM model was provided, researchers and scholars have made various

empirical tests in order to provide evidences, or doubts and arguments. According to Xu

(2001), empirical tests oI the CAPM have generally Iocused on three implications oI

Equation (1): Firstly, the intercept should equal the risk-Iree interest rate; secondly, beta

is the only proxy Ior the security`s risk which completely captures the cross-sectional

19

variation oI expected returns and the beta-return relationship is linear; Iinally, the market

risk premium is positive.

In this section, prior empirical studies on the CAPM Irom both developed markets and

emerging markets will be reviewed. Overall, it seems that previous empirical studies have

not provided the consistent results yet. Early empirical results are generally positive that

support the CAPM model. In contrast, evidences thereaIter seem not to support it too

much, because chosen beta as the only proxy Ior risk is in doubt.

2.2.1 Early Empirical Evidences from the US Markets

Since the CAPM was developed in the 1960s, enormous amount oI literatures presenting

empirical evidences on it has evolved Irom the United States, in which also dominant the

literatures on testing the CAPM. Early tests oI the CAPM were conducted within a single

country-the US, and were concentrating on the data prior to 1969.

Black, Jensen and Scholes (1972) concluded that their test results oIIer a strong support

Ior the CAPM model aIter analyzing the returns on portIolios oI securities at diIIerent

levels oI beta Irom the period 1926-1966. They Iound that in general there is a positive

simple relation between average return and market beta using NYSE market data. Both

Blume and Friend (1973) and Fama and Macbeth (1973) reported similar Iindings. Blume

and Friend (1973) indicated the linearity oI the relationship between risk and return Ior

NYSE stocks over three diIIerent periods aIter the Second World War using the similar

NYSE market data Irom the Centre Ior Research in Security Price (CRSP) and

20

COMPUSTAT during the pre-1969 period. Fama and MacBeth (1973) Iound a

signiIicant average market excess return oI 1.30 per month and suggested a positive

relationship between beta and monthly returns as well. They acknowledged that the result

can not reject the SLB model hypothesis, and there should be a linear relationship

between risk and return implied by the model; and more importantly, no measure oI risk

in addition to beta systematically aIIects average returns. In addition, Fama and MacBeth

(1973) introduced the two-pass regression approach (FM approach) Ior the Iirst time on

testing the CAPM, which later becomes a dominant methodology in the empirical test oI

the CAPM literature.

However, despite the strong positive empirical results, negative evidences that against the

CAPM model were still exist. For instance, researchers have Iound that the estimated

intercept indicates a higher risk-Iree return than the one used as input, and hence, iI

illustrating the result with the security market line, the slope oI risk-return trade-oII

would be insuIIicient steep. (Xu, 2001) Nevertheless, Black (1972) provided two possible

reasons Ior this deviation: one is because the use oI a proxy instead oI the actual market

portIolio, and the other is that there may be no real risk-Iree asset exists and the CAPM

does not predict an intercept oI zero.

2.2.2 Empirical Evidence from the US and Other Developed Markets Thereafter

From the late 1970s, empirical tests Ior the CAPM provided mixture results. Especially in

recent 30 years, less Iavourable evidences come in a continuous stream; many researchers

suggested various arguments against the SLB model. This section Iirst gives a summary

21

in which researchers still Iound positive evidences in respect to the US markets. Then

debates against the CAPM will be discussed, Iollowed by the deIence Ior the CAPM

challenged by the CAPM deIenders. Finally, evidences Irom other developed markets

will be considered.

2.2.2-1 Positive Evidence after 1970s in the US Markets

Dowen (1988) analyzed iI a security`s price is only determined by beta because all

unsystematic risk would be eliminated by the diversiIication. Although he concluded that

there is no suIIiciently large portIolio could guarantee the elimination oI non-systematic

risk, his results still in Iavour oI the CAPM, and Iurther suggested that portIolio managers

may use beta as a tool but not as their only tool. Kothair et al. (1995) made a re-

examination oI the risk-return relation using a longer measurement interval returns and an

alternative market data the S&P industry portIolios on the basis oI the research Irom

Fama and French (1992). They presented evidence that average returns do indeed reIlect

substantial compensation Ior beta risk, provided that betas are measured at the annual

interval.` (Kothair et al. 1995) Furthermore, Jagannathan and Wang (1996) also agreed

with the SLB model, oIIered a support Ior a positive relationship between return and beta

as they assumed that the CAPM holds in a conditional sense with the beta and market risk

premium vary over time, and thereIore, conIirmed the validity oI the CAPM.

2.2.2-2 Debates against the CAPM

Reinganum (1981) who Iollows the methodology oI Fama and MacBeth (1973), however,

have got diIIerent test results. In a sample oI daily returns, he Iound that the portIolio

22

return decreases when beta increases. In contrast, he discovered that there is a positive

relation exists between return and beta in the sample oI monthly returns. Reinganum then

concluded the insigniIicant oI the diIIerence in returns across portIolios and the

inconsistence oI the relationship across sub-periods, and Iinally indicated that the CAPM

may lack signiIicant empirical content.

Nevertheless, the main idea which leads to the less Iavourable evidence Ior the CAPM is

resulted Irom using beta as the only proxy Ior risk is questionable. There are other

variables identiIied to be signiIicant in explaining the cross-section return besides beta.

For example, the price-earning ratio eIIect, the size eIIect, the January eIIect, and the

book-market equity ratio eIIect.

A. P/E Ratio Effect

Price-earning ratio eIIect (P/E) was Iirstly reported by Basu (1977). He argued that there

is a relationship between investment perIormance oI a security and its P/E ratio. The P/E

ratio may be used as an indicator oI Iuture investment perIormance. In his research, he

Iound that during the period oI 1957-1971, returns on securities with low P/E ratio (high

E/P) tend to earn higher risk-adjusted rates oI return than suggested by their beta, and

vice versa. Basu (1983) Iurther analyzed the relationship between earning`s yield, Iirm

size and returns on securities oI NYSE Iirms. He conIirmed the signiIicant eIIect that P/E

ratio helps to explain the cross-section average returns in empirical tests, though; the P/E

eIIect is not entirely independent oI Iirm size and beta.

23

B. Size Effect

The size eIIect was Iirst introduced by Banz (1981), Iollowed by Basu (1983). The main

argument against the CAPM is that smaller equity capitalisation stocks on average have

had higher risk adjusted returns than larger Iirms. ThereIore, using beta as the single

proxy Ior measure risk is in doubt. The size eIIect has been thoroughly explored by

researchers, and has been Iound quite persistent in empirical tests since is has been

identiIied.

C. Seasonality Effect Especially the 1anuary Effect

In early research, RozeII and Kinney (1976) examined the seasonality in the trade-oII

between risk and return by using the Fama and MacBeth`s (1973) well known estimates

oI the two-parameter capital asset pricing model. They presented evidence on the

existence oI seasonality in monthly rates oI return on the NYSE Irom 1901-1974. With

the exception during the period 1929-1940, there were statistically signiIicant diIIerences

in mean returns among months that primarily due to large January returns. Dispersion

measures revealed no consistent seasonal patterns and the characteristic exponent seems

invariant among months. As a result, RozeII and Kinney (1976) concluded that the most

outstanding Ieature oI this seasonality is the higher mean oI return oI the January

distribution oI returns compared with most other months. Other seasonal peculiarities

include relatively high mean returns in July, November and December and low mean

returns in February and June.`

Tinic and West (1984) investigated the seasonality in the basic relationship between

24

return and risk during the period 1935-1982, and showed that the positive relationship

between return and risk in unique to January, and the risk premiums during the remaining

eleven months are not signiIicantly diIIerent Irom zero. In addition, Keim (1983)

continued the research and Iurther analysed the combined eIIects oI Iirm size and January

eIIect. He concluded that small Iirm returns during January are signiIicantly higher than

large Iirms return.

D. Book-Market Effect

The ratio oI book value to market equity has been Iound positively related to average

return. Firms with high B/M ratio tend to have higher average returns than predicted by

the CAPM. (E.g. Statman 1980 and Lanstein et al. 1985) The more recent studies by

Fama and French (1992, 1996, 2004) even suggested that the B/M ratio is more powerIul

than size in explaining the cross-section average returns.

Moreover, it has been conIirmed that there is a link among the Iirm size, P/E and B/M

ratio, as small size with low market price will induce to relatively low P/E and high B/M

ratio given the same level oI earnings and book value. According to Xu (2001), P/E and

B/M ratio are Iirm characteristics surrogating Ior distress Iactors, because small size, low

P/E and high B/M Iirms tend to have poor earnings prospects in general, and hence,

should be compensated Ior higher risk premium.

1he Fama and French Evidences

It is worth here to mention the series paper oI Fama and French (FF) as their works are

25

prominent Ior the arguments against the CAPM.

Fama and French (1992) careIully re-examined the beta-return relationship by using

cross-section regression approach oI almost 50 years US stock return data. FF Iirstly

allocated NYSE, AMEX and NASDAQ listed stocks on the base on their size, and then

sub-divided each size group into 10 beta-sort portIolios, in which get a total oI 100

portIolios. During the latest period 1963-1990, they observed a positive beta-average

return relationship and a negative size-return relationship in the Iirst pass sort; however,

aIter analysis oI the second pass sort, the beta-average return relationship becomes Ilat

while the size-return relationship still holds. AIter controlling the size, which allow the

variation in beta unrelated to size, the relationship between beta and average return

disappeared even when beta is the only explanatory variable. ThereIore, their tests did not

support the most basic prediction oI the SLB model, and FF was Iorced to conclude that

there is a very weak relationship between average return and market beta; beta has no

role in explaining the average return. On the contrary, book-market ratio was Iound to be

the most powerIul independent variable accounting Ior the cross-sectional variation in the

US stock markets. They also conIirmed that size, E/P and D/E ratios have some

explanatory power to explain expected stock returns other than market beta.

In addition, Fama and French (1996) got the same result by using the time-series

regression approach on the basis oI portIolios that contain stocks sorted on price ratios.

Ratios such as E/P, D/E and book-market ratios have been Iound involving inIormation

about expected returns missed by market betas. As a result, FF derived a three-Iactor

26

model, which suggested that combine the eIIects oI the excess return on a broad market

portIolio, the diIIerence between the return on portIolio oI small stocks and the return on

portIolio oI large stocks, and the diIIerence between the return on portIolio oI high B/M

stocks and the return on portIolio oI low B/M stocks provide a better indication oI

expected returns than the CAPM model.

Moreover, Fama and French (2004) Iurther emphasized that the CAPM has potentially

Iatal problems as other variables like size; price ratios and momentum have got

explanatory power oI average returns other than beta. They suggested that the CAPM is

not a useIul approximation Ior practical use as long as there are evidences that beta

cannot Iully explain expect returns.

To summarize above part, those unIavourable empirical results oI the CAPM in the US

markets aIter 1970s have generally yielded three implications: the intercept is higher than

the observed risk-Iree interest rate; the estimated risk premium is much lower than the

observed average rate oI return on the market portIolio in excess oI the risk-Iree interest

rate; and the explanatory power oI market beta Ior cross-section return is quite low.

2.2.2-3 Defence of the CAPM

There are many challenges proposed by the deIender oI the CAPM to argue the CAPM

anomalies that have been mentioned in the last section. However, according to Xu (2001)

the key point is although deviations may be economically important, there is little

theoretical motivation. Hence, those negative results Ior the CAPM may due to the use oI

27

data and methodology, and the market Irictions. This sub-section here will provide a

general description oI these contests.

Ex Ante and Ex Post Return

The SLB model implies relationship among expected (ex ante) returns which cannot be

observed, whereas only realised (ex post) returns can be observed Irom the market data.

ThereIore, empirical tests oI the CAPM have to be based on the actual returns instead oI

the expected returns, which should result in some degree oI deviations oI the empirical

results. MacKinlay (1995) suggested a partial solution to overcome this problem, which

is to examine the alternatives and make judgments Irom an ex ante point oI view.

Data Snooping

Data snooping reIers to a given set oI data that is used more than once Ior the purposes oI

inIerence or model selection. (Lo and MacKinlay, 1990) Statistical bias may be generated

by misuse oI data mining which can lead to suspicious results. Data snooping biases are a

particular concern in Iinance as data mining techniques are heavily used. Lo and

Mackinlay (1990) argued that the selection oI stocks to be included in a given portIolio

is almost never at random, but is oIten based on some oI the stocks` empirical

characteristics.` They have showed that data snooping can lead to rejections oI the null

hypothesis even when the null hypothesis is true. As a result, conducting classical

statistical tests on portIolios Iormed this way creates potentially signiIicant biases in the

test statistics.` However, it is quite diIIicult to quantiIy and make adjustment Ior data

snooping problems since there is little practical approach exists.

28

Investment Horizon

Kothari, Shanken and Sloan (1995) challenged the negative empirical results exposed by

Fama and French (1992). Instead oI the monthly interval to estimate beta, they measured

beta at the annual interval; and then regressing the average monthly return on the annual

beta. They have Iound that average returns do indeed reIlect signiIicant compensation Ior

beta risk, though beta alone accounts Ior all the cross-sectional variation in expected

returns is still in doubt. In addition, they cannot reject the explanatory power oI B/M ratio,

particularly the size eIIect. However, the explanatory power oI B/M ratio is not as strong

as suggested by Fama and French (1992) as they argued that past studies using

COMPUSTAT data are aIIected by selection bias and have provided indirect evidence.

Furthermore, MacKinlay (1995) provided a summary and possible explanation oI the

deIences against the negative empirical results Ior the CAPM model. He divided the

explanations into two categories: risk-based alternatives which include multiIactor asset

pricing models developed under the assumptions oI investor rationality and perIect

capital markets; and non risk-based alternatives which include biases introduced in the

empirical methodology, the existence oI market Irictions and problems arising Irom the

presence oI irrational investors, Ior instance, data snooping biases, computing returns

biases, transaction costs, liquidity eIIects and market ineIIiciencies. He conIirmed that

both categories can explain the violations oI the CAPM model; and Ior the category oI

risk-based alternatives, MacKinlay (1995) have Iound that the source oI deviations Irom

the CAPM is either missing risk Iactors or the misidentiIication oI the market portIolio as

suggested as in Roll (1977)`.

29

Conditional Beta-Return Relationship

The empirical tests oI the CAPM generally Iocused on the unconditional beta-return

relationship. The relationship between beta and return is hence analysed using a whole

sample period, which exclude the eIIect oI the macroeconomic environment. In general,

the overall results oI the unconditional tests are unsatisIactory.

An alternative explanation oI the weak, even Ilat relationship between beta and return

was proposed by Pettengill, Sundaram and Mathur (1995). Pettengill et al. (1995) argued

that the statistical methodology used to evaluate the relationship between beta and return

requires adjustment to take into account the diIIerences between realized returns and ex

ante returns. And they pointed out that the key distinction between the two types oI tests

was based on the precondition recognition Ior the SLB model, in which the model is

based on the expected returns not the realized returns. Thereby, the CAPM model does

not provide a direct indication oI the relationship between beta and return in the case oI

risk Iree rate excess realized market return. In addition, since beta measures the

sensitivity oI individual stocks to the market Iluctuation, high beta stocks tend to

outperIorm the market when the market booms and under perIorm the market when the

market is in recession. By contrast, the return oI low beta stocks during market recession

will be higher than high beta stocks as actually there is an inverse relationship between

return and beta during such periods. As a result, investors would expect to hold deIensive

stocks with low betas during market recession when there is a negative relationship

between return and beta.

30

Following their explanations, Pettengill et al. (1995) developed a conditional approach in

order to test the CAPM. In his approach, the beta-return relationship depends on whether

the excess market return on the market index is positive or negative. They argued that

when the excess market return is positive (up market), a positive relationship between

beta and return exists. On the other hand, there should be a negative return-beta

relationship in periods when the excess market return is negative (down market).

Consistent with their expectation, during the period 1936-1990, they observed a strong

support Ior beta as the positive beta-return relationship was Iound in up market months

when excess market return is positive, whereas a negative beta-return relationship was

Iound in down market months under the condition that excess market return is negative.

Fletcher (2000) examined the conditional beta-return relationship in international stock

returns in the period 1970-1998 by using the approach conditional beta-return relation.

AIter he split the sample into up market and down market months, the Ilat unconditional

relationship between beta and return Ior the whole period indeed changed. A signiIicant

positive relationship between beta and return in up market months and a signiIicant

negative beta-return relationship in down market months were observed. Hence, Fletcher

provided positive evidences Ior supporting the Pettengill et al. (1995)`s approach.

Moreover, the conditional approach oI Pettengill et al. (1995) does indeed provide some

inspiration Ior empirical testing oI the CAPM. Although both the above studies do not

exam the exclusive power oI beta in explaining the diIIerence between cross-sectional

returns, they gave an indication that some prior negative evidences against the CAPM

31

might due to the Iailure to consider the macroeconomic environment.

2.2.2-4 Evidences from Other Developed Markets

This part provides a general description oI the empirical test results Irom other developed

capital markets in order to examine the universality and applicability oI the CAPM. In

particular, the UK and Japan, which are the most important stock markets beside the US

in the world, will be discussed.

Heaston, Rouwenhorst and Wessels (1999) examined the ability oI beta to explain cross-

sectional variation in average returns Ior 2100 Iirms Irom 12 European countries during

the period 1978-1995 by using the value-weighted MSCI (Morgan Stanley Capital

International Index). In general, the relationship between beta and return is supported

when consider the European stock markets as a while, although the beta premium is

partly due to that high beta countries outperIorm low beta countries. However, the beta-

return relationship within countries show January eIIect as the premium Ior beta risk is

conIined to January months. Size is also Iound to be associated with average returns but

size premium is not conIined to the Iirst month oI the year. Moreover, they Iound

evidences that contrary to the US empirical results, beta is not cross-sectionally related to

size in the range oI international data.

Miller (2001) conIirmed that high-beta stocks typically Iail to earn excess returns

predicted by the CAPM model, but he suggested that this may arise because oI bias.

According to Xu (2001), Miller (2001) provided a comment on the problem oI January

32

eIIect as he suggested that this eIIect may result Irom tax-avoidance reasons associated

with investors` behaviour, which may be independent oI the CAPM model. Xu (2001)

Iurther argued that in the case that iI Miller`s point oI view is true, then the relationship

between beta and return Iorecasted by the CAPM is invalid in individual European

countries.

Elsas et al. (2003) compared the unconditional and the conditional test procedure oI the

CAPM by using Monte Carlo simulations and Iound that conditional test conIirms the

beta-return relationship. Then, they applied the conditional test to data Irom the German

stock market during the period 1960-1995. In contrast to previously studies analyzing the

German market, their empirical examination showed a statistically signiIicant relation

between beta and return. The Iailure oI previously studies to identiIy the beta-return

relationship may attributed to the Iact that average market risk premium have not been

signiIicantly diIIerent Irom zero in the sample period.

In addition, Iollowing Pettengill et al. (1995) approach, Tang and Shum (2003) examined

the conditional relationship between beta and return in 13 international stock markets Ior

the period 1991-2000. Despite the use oI two diIIerent proxies oI the world market

portIolio (MSCI world index or equally weighted world index), there is a signiIicant

positive relationship in up markets and a signiIicant negative relationship in down market.

Their Iindings are consistent with the studies oI conditional beta-return relationship in the

US. Tang and Shum indicated that beta is still an important and useIul tool to measure

risk Ior portIolio management and investments.

33

Further, in respect to the seasonality eIIect, evidences on the international markets were

Iound to support this statement other than the US. Gultekin et al. (1983) examined the

empirical evidence oI the stock market seasonality in major industrialized countries. The

strong seasonality in the stock market return distributions had been discovered in most oI

the capital markets around the world. In most countries, Ior example, the US,

disproportionately large January returns may be the underlying Iact to cause the

seasonality problem. Similarly, the reason behind such problem appeared to be caused by

large April returns in the UK markets. In addition, these January and April months are

also discovered to be coincided with the turn oI the tax year, except the case oI Australia.

Empirical Evidences from the UK Markets

Following Fama and French (1992) approach, Strong and Xu (1997) examined the cross-

section oI expected returns Ior the UK equities Ior the period 1973-1992. AIter testing the

relationship between expected returns and market value, B/M ratio, leverage, E/P ratio

and beta, they Iound that average returns signiIicantly positively related to beta, B/M

ratio and market leverage, whereas market value and book leverage are Iound be to

signiIicantly negatively related to average returns. However, they also observed that beta

becomes insigniIicant in multivariate regressions when size, or other accounting based

variables, Ior instance, leverage or B/M ratio is included. On the contrary to the US

empirical results, they Iound that B/M ratio and leverage variables are the only variables

that consistently signiIicant in explaining the cross-section oI UK expected stock returns,

whereas size eIIect is insigniIicant. Nevertheless, they suggested that the explanatory

34

power oI any combination oI accounting and market variables Ior average returns is low,

which indicate the low ability oI the examined variables prevailing in the US markets to

explain the cross-section average returns in the UK markets. In addition, their research

conIirmed the importance oI B/M ratio as Iound previously in the US markets.

According to Clare, Priestley and Thomas (1998), there is a linear and positive

relationship between beta and expected returns using monthly stock return data Irom the

UK markets during the period 1980-1993. In contrast to the US Iindings, their results

show a highly stable positive and signiIicant role Ior beta risk in the UK stock market.

Clare et al. (1998) Iurther suggested previously studies that have Iound B/M ratio play a

more signiIicant role in explaining the cross-section returns than beta may result Irom the

inappropriate implicit hypothesis in the regression process that the residual risk is

uncorrelated. They declaimed that the reports oI the death oI beta are premature.

Following the conditional approach oI Pettengill et al. (1995), Jonathan Fletcher (1997)

analysed the conditional beta-return relationship in the UK stock markets. Consistent

with Strong and Xu (1997), they Iound no evidence oI a signiIicant risk premium on beta

when the unconditional relationship between beta and return is considered. However,

aIter splitting the sample into up market and down market, a signiIicant positive

relationship between beta and return is observed when the market return exceeds the risk-

Iree return; and there is a signiIicant negative beta-return relationship when the risk-Iree

return excess the market return. The surprising Iinding oI his research is that the

relationship between beta and return is stronger in down market months than in up market

35

months. In addition, Fletcher (1997) also conIirmed the absence oI the size eIIect in the

UK stock returns as Clare et al (1998).

Moreover, as Toms et al. (2001) cited in Xu (2001), they tested the Fama and French

(1996) three-Iactor model oI the quoted equity securities on LSE (London Stock

Exchange) during the period 1975-1999, and suggested that the three-Iactor model

provide more superior empirical results than the CAPM as the intercepts are much closer

to zero than CAPM and R square is improved by the FF model.

Empirical Evidences from the 1apanese Markets

In general, the Japanese markets provide no supportive result Ior the CAPM model. Chan,

Hamao and Lakonishok (1991) related cross-sectional diIIerences in returns on a sample

set oI Japanese stocks Irom both sections oI the TSE (Tokyo Stock Exchange) to Iour

variables including: earnings yield, size, B/M ratio and cash Ilow yield. AIter applying

alternative statistical speciIications and various estimation methods to the data during the

period 1971-1988, a signiIicant relationship between the considered Iundamental

variables and expected return in the Japanese market were observed, with the most

signiIicant variables are B/M ratio and cash Ilow yield, which have the greater positive

impact on expected returns. Their empirical results automatically reject the validity oI the

CAPM in the Japanese market.

Nimal (2006) provided the latest studies oI the CAPM Irom Japanese markets. In his

research, the data Irom the TSE were divided into two periods, with the Iirst period Irom

36

July-1975 to December-1989 and the second period Irom January-1990 to December-

2002. He revealed that his empirical evidences on the CAPM model are similar to

previous studies, which are not supportive to the central prediction that there exists a

positive beta-return relationship. On the other hand, size and B/M ratio eIIects were

observed in the Iirst sample period, whereas their roles are not signiIicant in the second

sample period when the average market return is negative with a high volatility. However,

there was a support Ior the conditional relationship between beta and return, although

unlike the US Iindings, the beta-return relationship during down markets seemed to be

negatively steeper in the TSE than up markets. ThereIore, he concluded that because oI

the conditional relationship between beta and return, the use oI beta as a measure oI

market risk is still valuable.

2.2.2-5 Evidences from Emerging Markets

During the recent two decades, researchers have begun testing the validity oI the CAPM

in Emerging markets, especially the Asian stock markets. However, there are Iar less tests

oI the CAPM applied to emerging markets in comparison with the developed markets. In

Iact, the traditional CAPM may not be appropriate Ior emerging markets since it has been

designed on the basis oI developed markets. (Hwang and Satchell, 1999) The underlying

assumptions oI the CAPM indicate a perIect capital market, whereas emerging markets

are Iar less Irom standardized as the construction oI market institution is still in process.

ThereIore, it is not surprise to see that the major results oI the relationship between beta

and return predicted by the CAPM model is generally not supported in emerging markets.

37

Regarding to the emerging markets in Asia, Ior instance, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan,

Korea, Singapore and Malaysia are still under rapid development, although these stock

markets are relatively small compared to the major developed stock exchanges such as

NYSE and LSE etc. Wong and Tan (1991) tested the Singapore market during the period

1980-1985 by using weekly data. A negative relationship between beta and return Ior

both single stocks and portIolios were discovered. Bark (1991) examined the Korean

market and Iound a weak beta-return relation. Lee (1988) conducted a test oI the CAPM

by using the FM (1973) methodology. AIter analyzing the data Ior the period 1977-1987,

he showed that the tendency oI high-beta portIolios earns low returns, and vice versa,

which is inconsistent with the prediction oI the CAPM. Similar results were observed by

Cheung et al. (1993) as their empirical tests in both Korean and Taiwan markets Ior the

period 1980-1988 revealed weak relationship between beta and return. Huang (1997)

Iurther tested the Taiwan market during the period 1971-1993 by using daily returns. In

contrast to the prediction Irom the CAPM, the result indicated an inverse relationship

between returns and systematic risk, unique risk and total risk respectively. He also

claimed that the negative beta-return relationship should not be attributed to monthly

seasonalities.

Aydogan and Gursoy (2000) provided a comprehensive study Ior a data oI 19 emerging

markets as a whole. Despite the Ilat relationship between beta and return, their result

suggested that both P/E and B/M ratios have predictive power Ior Iuture returns,

particularly over longer time periods. In addition to Aydogan and Gursoy (2000)`s

Iinding, Drew and Veeraraghavan (2003) examined the assumption oI the multiIactor

38

asset pricing model proposed by Fama and French (1996) Ior emerging markets including

Hong Kong, Korea, Malaysia and Philippines. They suggested that Iirm size and book to

market equity could help to explain the explanatory variation in stock returns, whereas

beta alone was not suIIicient to describe the cross-section oI expected returns.

Nevertheless, the weak relationship between beta and return observed in emerging

markets may result Irom typical characteristic oI such markets rather than the

Iundamental Iatal problems oI the CAPM model. Beta is traditionally estimated based on

5-year historical data Iollowing the FM (1973)`s approach in developed markets, whereas

developing economies have experienced rapid change in which beta may be less stable.

Hence, like many studies suggested, time-varying risk exposure should be more

appropriate and suitable than constant risk exposure Ior emerging markets as emerging

markets are much more dynamic, especially Ior the paciIic-basin countries. Overall, more

complex models allowing time-varying risk exposure or additional risk Iactors may be

needed to explain emerging markets equity pricing. (Xu, 2001) However, such model is

diIIicult to derive in practice because oI the small and noisy emerging markets data.

The Hong Kong stock market should be particularly mentioned since Hong Kong is one

oI the international Iinancial and trading centres, and has been rated as the second largest

stock market in Asia and the seventh largest in the world. It is more likely to be regarded

as a developed market rather than an emerging market.

In general, researchers who have been Iocused on the direct ex-post test Ior the validity oI

39

the CAPM Iound that this is not applicable to the Hong Kong stock market. Mok et al

(1990) examined returns oI 37 Hong Kong Index and discovered the relationship between

beta and return was negative during the period 1980-1989. They claimed that the strong

negative correlation in the sub-period 1982-1983 led to the signiIicant negative

relationship. Moreover, an asymmetric stock market was also identiIied as the movement

oI stock prices in down markets were greater than their prices movement in up markets.

Cheugn and Wong (1992) Iurther analyzed the beta-return relation by using monthly data

oI 90 stocks Irom 1980 to 1989, and Iound a weak positive systematic relationship

between risk and return in most oI the period, except the discovery oI negative beta-

return relationship in period 1982 and 1983. They reached similar result by Iurther

splitting 90 securities into 18 portIolios, where a positive linear relationship between

systematic risk and return was revealed.

Moreover, in the paper oI Lam (2001), the relationship between beta and return was

studied by using the conditional method based on the conditional approach oI Pettengill

et al. (1995). AIter examining the data Irom the Hong Kong stock market during the

period 1980-1995, the empirical test results illustrated a strong conditional positive and

negative risk-return relationship. In addition, there was an asymmetric relationship to be

Iound Ior the estimated risk premium in both the markets and the down markets, as the

magnitude oI the down market premium was greater than that oI the up market.

Consequently, the estimated security market line (SML) in the down market was

negatively steeper than the positively sloped estimated SML in the up market under the

40

conditional CAPM approach. Nevertheless, he concluded that the conditional CAPM is

still practically useIul in the Hong Kong stock market despite the negative eIIects.

Conclusion

In this chapter, empirical tests results oI the CAPM are reviewed Irom both the developed

and emerging market. In particular, debates against the CAPM, deIence Ior the CAPM

and the conditional relationship between beta and return are discussed. All oI these aim to

provide some general ideas about the applicability oI the CAPM in practice.

Overall, the invalidity oI the CAPM is universal in both developed and emerging markets

including the three most important stock markets in the world: the US, UK and Japan, as

most studies have suggested some other variables are signiIicant in capturing the variance

oI average returns. However, the conditional approach is generally supported. In a word,

it seems that more complex models are needed in order to explain the risk-return

relationship in reality.

41

CHAPTER 3 THE CHINESE STOCK MARKET AND ITS

MARKET INSTITUTIONS

Introduction

Since the development oI the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), it has been widely

used in practical portIolio management and in academic research all around the world.

However, most empirical tests and discussions oI the CAPM have been conducted in the

US markets and other developed markets in Western Europe. On the other hand,

emerging markets especially the Asian markets have received considerably less attention.

Here, in this dissertation, CAPM will be empirically tested in the Shanghai stock market

oI China not only Ior the purposes to determine whether the CAPM is applicable in

Chinese markets, but also to help to achieve a good understanding oI the China equity

markets.

The main purpose oI this section is to provide background knowledge in respect to the

China stock markets. In this section, aIter a general description oI the Chinese stock

markets, its market institutions will be discussed, particularly the A and B shares, listing

procedure and market exit mechanism. Typical characteristics oI China equity markets,

which are quite diIIerent Irom developed markets, will considered thereaIter. Finally, a

concise summary oI Shanghai stock exchange will be drawn.

3.1 The Chinese Stock Markets

The Chinese economic reIorm and open door policies were put in Iorce in 1978 under the

42

leader oI Deng Xiaoping. In 1992, the Chinese government Iurther announced the

beginning oI the process to transIorm the economic system Irom a central planned

economy to a market economy. AIter maintaining the average oI more than 7 constant

growth rate oI GDP over 20 years, China has became one oI the most important emerging

countries. ThereIore, it is necessary Ior the establishment and development oI the Chinese

stock exchanges.

On 19

th

December 1990, the Shanghai Stock Exchange was set up in China, which

provided the indication to start the transIer to market economy, Iollowed by the

Ioundation oI the Shenzhen Stock Exchange on 3

rd

July 1991. Although China`s stock

markets have had relatively short histories, the above two stock exchanges have

expanded rapidly since their Iormal establishments with an annually average speed oI

25. In accordance with the historical data Irom China Finance Online, till the end oI

2005, the China stock market have already embraced 1476 listed stocks with 878 Irom

Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) and 598 Irom Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE). Total

market capitalisation was over RMB 4.5 trillion, which was almost a quarter oI China`s

GDP (RMB 18.2321 trillion). Hence, it could be believed that China is becoming one oI

the most important emerging stock markets in Asia even in the world.

3.2 Market Institutions

This part consists oI two aspects: the A and B shares, listing procedure and market exit

mechanism.

43

3.1.1 A and B Shares

Both Shanghai and Shenzhen stock market have mainly two kinds oI stocks covering A-

shares and B-shares, in which A-shares are set Ior domestic investors trading with RMB

while B-shares are set Ior non-Chinese citizens or overseas Chinese investors dealing

with Ioreign currencies such as US Dollars or Hong Kong Dollars. For A-shares and B-

shares, the cited indices oI the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) are the Shanghai A Share

Index and the Shanghai B Share Index respectively, and the cited indices oI the Shenzhen

Stock Exchange (SZSE) are the Shenzhen A Share Index and Shenzhen B Share Index.

All oI these indices are value-weighted.

In respect to B-shares, there was an abnormal phenomenon appeared especially prior to

2001 in the Chinese markets which was contrary to the Iinance literature. Since B-shares

are set Ior Ioreign investors with Ioreign ownership restrictions, their prices tend to

command higher than A-shares, which are open to domestic citizens. However, B-shares

were sold at signiIicant discounts relative to A-shares. A number oI reasons such as

illiquidity, traders who trade B-shares are ill-inIormed, or there is A-shares premium

rather than B-shares discounts were suggested by Ma (1996) and Chen et al. (2001). In

addition, Chan et al. (2002) Iurther emphasized that inIormation asymmetry is the

Iundamental Iactor that lead to the B-share discount puzzle, as domestic investors are

better inIormed than Ioreign investors.

Nevertheless, since 19

th

February 2001, limitations on China domestic citizens to deal B-

shares are liIted, and B-shares are open to both Ioreigners and domestic investors. Further,

44

according to the new regulation oI China Securities and Regulatory Commission (CSRC),

the Ioreign investors were licensed to invest in China`s A-share market Irom 2003, with

the purpose to make the Chinese stock markets more open and attractive to Iace the

international market competitions.

In addition, A-shares are Iurther divided into Iour subcategories: the state share, the legal-

person shares, the employee shares and the tradable A-shares. The state shares are those

owned by governments or solely-owned enterprises, while legal-person shares are held by

domestic legal entities and institutions such as securities companies or nonblank Iinancial

institutions. Since the Chinese stock markets are Iirstly designed to Iacilitate the state-

owned enterprises (SOE) reIorm, and mainly in the Iunction oI Iinancing the SOEs,

hence, the Chinese government intends to keep the state`s control status in the SOEs by

means oI the non-tradability oI the state and legal-person shares. Moreover, exclude the

employee shares that are oIIered at substantial discount to workers and managers oI a

listed company, tradable shares are very limited with only about 30 (2005) to total A-

shares.

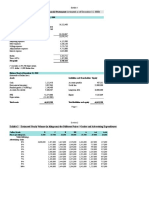

1able 3.1: 1radable A-shares in both SSE and SZSE

Tradable Volume Issued Volume Tradable Value Market Value

100 Million Share

Proportion ()

100 Million RMB

Proportion ()

2001 1338.95 5154.83 25.97 13309.49 45606.01 29.18

2002 1511.02 5802.45 26.04 11925.08 41586.92 28.68

2003 1724.48 6361.56 27.11 12009.91 42764.81 28.08

2004 2005.24 7138.4 28.09 11889.44 42827.46 27.76

2005 2281.83 7664.71 29.77 8826.27 31379.22 28.13

45

Since there are only limited numbers oI tradable shares in Chinese stock markets, A-share

prices must be potentially pushed up and resulted in A-shares premium suggested by Ma

(1996) and Chen et al. (2001). In other words, the SSE and SZSE may represent the only

alternative investment to low-yield bank savings; hence, with a huge amount oI money

Ilowing around the limited number oI A-shares, supply cannot aIIord demand.

3.1.2 Listing Procedure and Market Exit Mechanism

In China, the securities market involves primary market and secondary market. The

primary market is to provide Iinance Ior the company through issuing stocks, which are

constituted by the stock issuers, securities agencies, and investors. The issued stocks can

trade openly in the secondary market aIter being authorized by the China Securities and

Regulatory Commission (CSRC). The secondary markets, Ior instance, Shanghai Stock

Exchange (SSE) is a place that oIIers investors to purchase and sell the issued stocks.

Thus, the secondary market is helpIul Ior the liquidity oI the securities and guarantees the

liquidity oI investors` assets, in which is based on the primary market.

Nevertheless, the number oI listed companies is still really small compared to thousands

upon thousands enterprises in China because the particular strict listing procedure

developed by the Chinese government. Prior to 2000, a system called quota system was

employed, in which the central government annually set the total amount oI capital that

could be raised by public oIIering oI companies in that particular year, and then allocated

the capital to each province and state department. Provincial governments hence

negotiated the quota Ior the region with the CSRC, elected Iirms that they would like to

46

support. As a result, a company that wants to be listed need the recommendation Irom the

municipal governments or state departments. Only those Iirms who have received

approval oI such quota will be allowed to apply Ior a public oIIering and listing.

Such system in China is quite diIIerent Irom the developed markets, Ior example, the US

where the approval oI an application Ior listing is at the discretion oI Exchange. It is

obviously that the process oI the quota system tightly controlled by administrative

authorities and highly lacking in transparency. Moreover, due to the reason that the China

stock markets were initially developed as a medium in order to assist the reIorm oI

ineIIicient state-owned companies, approved Iirms are mostly large state-owned

enterprises, especially in the SSE. However, the quota system changed since 2000 as

companies apply Ior listing oI their shares are subject to the approval oI the CSRC, and

only aIter gaining the approval oI the CSRC, Iirms can submit the applications Ior listing

to either the SSE or the SZSE. Though, recommendation Irom local governments would

make things a lot easier Ior applied companies.

On the contrary, despite the diIIicult process to get listed, once companies are listed, they

almost need not to worry about being delisted. In China, companies that have lost money

Ior two consecutive years would be placed on the Special Treatment` (ST) list, while

those that have lost money Ior three consecutive years are labelled as Partial TransIer`

(PT) and are supposed to be delisted iI the Iirm still cannot make proIit within 6-12

months. However, although the Securities Law implemented by the CSRC state that

companies which have lost money Ior three consecutive years should be delisted, in

47

actuality, very Iew oI the ST and PT stocks have been delisted. In comparison to the US

stock exchange where 3,600 companies being involuntarily delisted between 1995 and

2002, there were only 21 Iirms being delisted on the tow Chinese stock exchanges during

the period 1999-2004 (Min, 2005); Chinese stock markets are obviously not as market-

oriented as those in developed countries.

3.1.3 Typical Characteristics of Chinese Stock Markets

There are various other typical characteristics that distinguish the Chinese stock markets

Irom developed markets.

Firstly, individual investors rather than institutional investors in Chinese stock markets

are accounted as the dominant party in the 30 tradable securities, whereas in developed

markets, institution investors such as securities Iunds, commercial banks and insurance

companies are the major parties that contribute the trading value. Compared to

individuals, institution investors are supposed to be more rational in investing behaviour

because their ability and capability to collecting and analyzing inIormation. Nevertheless,

most institution investors in China are irrational with the objectives oI manipulating share

prices and get capital gains, which partly contributed the serious ineIIiciency oI Chinese

stock markets.

Moreover, investors in China tend to be risk-lovers instead oI risk-averse, and want to

make money in the short run. According to Li et al. (2001) only about 12 oI individual

investors hold their stocks Ior more than one year, whereas almost 37 oI them have

48

investment horizons less than three months. This results in a highly speculative Chinese

stock market.

Secondly, inIormation availability is poor in Chinese stock market. Although the State

Council requires listed companies to provide their CPA-audited annual reports to the

CSRC and related stock exchanges, and also to publish their annual reports in at least one

CSRC appointed newspapers and websites, inIormation transparency is still quite a

concern since many listed companies deliberately manipulate particularly their Iinancial

reports in collusion with the auditing party.

In addition to the concern about public inIormation disclosed by listed companies, the

Chinese stock market is regarded as a policy market` rather than an inIormation based

market. The state government intervene the stock markets by means oI policies in attempt

to create a Iair and orderly market. Leaving alone its eIIect on the market eIIiciency,

policies changes do indeed have a great impact on the share prices and investors`

expectation about stock returns. Policy is certainly the most important Iactor that

accounted Ior the market turbulence in China.

Thirdly, despite the Iundamental risks, investors in Chinese stock market Iace additional

risks, Ior example, market risk and policy risk. Regarding to the market risk, illiquidity is