Professional Documents

Culture Documents

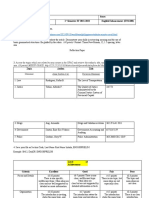

Zsiga, E (206) Assimilation PDF

Uploaded by

joagvidoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Zsiga, E (206) Assimilation PDF

Uploaded by

joagvidoCopyright:

Available Formats

Assimilation 553 Exploring the potential of an information processing approach to task design. Language Learning 51(3).

Jacoby S & Ochs E (1995). Co-construction: an introduction. Research on Language and Social Interaction 28(3), 171183. Kane M T (1992). An argument-based approach to validity. Psychological Bulletin 12, 527535. Kane M T (2001). Current concerns in validity theory. Journal of Educational Measurement 38(4), 319342. Kunnan A J (2000). Fairness and justice for all. In Kunnan A J (ed.) Fairness and validation in language assessment. Selected papers of the 19th Language Testing Research Colloquium. Orlando, FL. Cambridge, UK: UCLES & CUP. 110. Lumley T & Brown A (2005). Research methods in language testing. In McNamara T, Brown A, Grove L, Hill K & Iwashita N (eds.) Handbook of research in second language learning: Part VI. Second language testing and assessment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. 833857. McNamara T F (2000). Language testing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. McNamara T F (2001). Language assessment as social practice: challenges for research. Language Testing 18(4), 333349. McNamara T F, Hill K & May L (2002). Discourse and assessment. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 22, 221242. Messick S (1989). Validity. In Linn R L (ed.) Educational measurement, 3rd edn. New York: American Council on Education, Macmillan. 13103. Mislevy R J, Steinberg L S & Almond R G (2002). Design and analysis in task-based language assessment. Language Testing 19(4), 477496. Mislevy R J, Steinberg L S & Almond R G (2003). On the structure of assessment arguments. Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research and Perspectives 1(1), 362. OLoughlin K (2001). The equivalence of direct and semidirect speaking tests. Studies in Language Testing 13. Cambridge, UK: UCLES and Cambridge University Press. Popham W J (1997). Consequential validity: right concern wrong concept. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice 16(2), 913. Rea-Dickins P (ed.) (2004). Special issue: exploring diversity in teacher assessment. Language Testing 21(3). Shohamy E (2001). The power of tests: a critical perspective on the uses of language tests. London: Pearson. Spolsky B (1995). Measured words. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Assimilation

E Zsiga, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA

2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Definition

Assimilation is a phonological process in which two sounds that are different become more alike. (The opposite of assimilation is dissimilation, in which sounds that are alike become different.) Assimilation may be either local, in which the two sounds must be immediately adjacent, or long distance, where one sound affects another even though other segments intervene. Local assimilation is the most common type of phonological process, and it can occur along just about any phonetic dimension, including place, voicing, nasality, continuancy, rounding, and palatalization. Assimilations may be partial or total. In partial assimilation, one segment comes to match another in one or more, but not all, phonological features. In total assimilation, two segments become identical. Both partial and total assimilation can be illustrated with the English negative prefix in-. The basic form of the prefix is [in-], as in inaccurate and insecure. In impossible, the [n] undergoes partial assimilation, changing to match the place of articulation of the following stop, but maintaining its

underlying nasality. In illiterate, the assimilation is total, with the [n] becoming identical to the adjacent [1]. Assimilations may also be distinguished by the direction in which the change occurs. In a sequence AB, if A changes to become more like B, as in [np] becomes [mp], the assimilation is termed regressive (as though B were reaching back to change A) or anticipatory (A anticipates a feature of B). If B changes to become more like A, the assimilation is termed progressive (A reaches forward to affect B) or perseverative (some feature of A perseveres into B). An example of progressive assimilation is found in the English past tense and plural suffixes, which are basically voiced (as in rowed [ro-d] and toes [to-z]), but become voiceless when preceded by a voiceless segment (as in cats [kt-s] and talked [tak-t]). Assimilation is sensitive to syllabic position and to prominence. For example, segments in the syllable coda assimilate to segments in the onset far more often than reverse (Ito , 1988; Beckman, 1998). Position in the word also plays a role: medial vowels assimilate to initial vowels, and affixes assimilate to roots. Steriade (2001) defines prominence in terms of perceptual salience, arguing that segments assimilate

554 Assimilation

in contexts where contrastive features can not be clearly heard: postvocalic consonants generally assimilate to prevocalic consonants, because release into a vowel provides the most salient cues to the phonological features of a consonant.

Examples

Local Assimilation, Partial

One of the most common assimilations crosslinguistically is nasal consonants assimilating in place of articulation to a following stop. Examples include English inaccurate vs. impossible and compact vs. contact vs. co[N]gress. In Twi, the negative prefix is also a nasal: [me-m-pE] I do not like, [me-n-tO] I do not buy, [me-0-0a] I do not receive, [me-N-ka] I do not say. For Catalan (CatalanValencian-Balear), Kiparsky (1985) reported nasal assimilation to seven different places of articulation:

(1) so[n] amics so[m] pocs so[M] felicos so[n 9 ] [d 9 ]os so[0] rics so[J] [y]iures so[N] grans they are friends they are few they are happy they are two they are rich they are free they are big

consonants: [kokusai] international, [kitai] expecta tion (Tsuchida, 1996). In Ancient Greek, obstruent clusters assimilated in both voicing and aspiration (Smyth, 1920): [graph-o] I write, but [gEgrap-tai] has been written and [grab-den] writing/scraping; [trib-o] I rub, but [tetrip-tai] has been rubbed and [etriph-the:n] it was rubbed. Vowels and consonants sometimes influence one another. In many languages, coronal consonants become alveopalatals before high front vowels or glides, assimilating the higher tongue position. English has alternations such as grade/gradual ([d]/[dZ]), habit/ habitual ([t]/[ts]), press/pressure ([s]/[s]). A vowel may also impose palatalization as a secondary articulation on a consonant, adding an additional high front tongue position without changing the consonants primary place: Russian [Zen-a] wife, [Zenj-i-tj] marry. The change of a stop to a fricative between vowels, as in Spanish [bola] ball, [la bola] the ball, is sometimes considered assimilation of the feature [continuant]. Assimilation of [-continuant] may be seen in postnasal hardening: Kikuyu [bur-a] lop off-IMP, [m-bur-eete] 1SG-lop off-IMPERF (Clements, 1985).

Local Assimilation, Complete

The feature [nasal] itself may assimilate (Cohn, 1990; Piggott, 1992; Walker, 1998). Vowels often become nasal adjacent to a nasal consonant. In French, [bon] good becomes [bo ]. In Sundanese (Sunda), [natur] arrange is pronounced [na tur] (Robins, 1957). Assimilation of nasality from consonant to consonant is found in Twi, when a root-initial voiced stop follows the negative prefix: [me-gu/] I pour, [me-n-nu] I do not pour. Another common assimilation is voicing assimilation. Clusters of obstruents often assimilate in voicing, usually regressively. In Russian, for example, a string of obstruents always agrees in voicing with the final obstruent in the sequence: [od vzbu tski] from a scolding, [ot fsple ska] from a splash (Jakobson, 1978). Generally, sonorants do not participate in voicing assimilation (note that the [l] in [fsple ska] neither becomes voiceless nor causes the preceding consonants to become voiced), though there are cases of sonorantobstruent voicing assimilations. Postnasal voicing is attested in a number of languages, for example Kikuyu (Gikuyu) [tEm-a] cut-IMP, [n-dEm-EEtE] 1SG-cut-IMPERF (Clements, 1985; see also Hayes, 1999 and Pater, 1999 for further examples and discussion). Voicing assimilation from consonant to vowel is found in Japanese, where high vowels become voiceless if surrounded by voiceless

Several African languages have rules of complete vowel assimilation at word boundaries (Welmers, 1973). In Yoruba, for example, [owo] money plus [epo] oil becomes [oweepo] oil money. In Igbo, [nwoke] man plus [a] DET becomes [nwokaa] that man. Total assimilation of consonants is found in English [in-] assimilation to [l] and [r] (mentioned above) as in illegal and irreconcilable. Another example of complete assimilation involving [l] is found in Arabic: the [l] of the definite prefix [ al] assimilates completely to a following coronal consonant: [ al-kitaab] the book but [ as-sams] the sun, [ ad-daar] the house, [ an-nahr] the river (Kenstowicz, 1994).

Long-Distance Assimilation

Long-distance assimilation is known as harmony. Vowel harmony is a type of assimilation in which all vowels in a certain domain (usually the word) must agree in one or more features. Vowel harmony has been extensively discussed in the phonological literature, and harmony systems involving backness, rounding, vowel height, and advanced vs. retracted tongue root have been described: see van der Hulst and van de Weijer (1995) for an overview. In

Assimilation 555

Hungarian, for example, suffix vowels assimilate in backness to the root vowel: [ha:z-nak] to the house, [va:ros-nak] to the city, [vi:z-nek] to the water, [yrnek] to the gap (Ringen, 1988; see also Vago, 1976, Goldsmith, 1985). In Turkish, high vowels agree with a preceding vowel in both backness and rounding, while nonhigh vowels agree in backness. Some oftcited examples from Turkish (Clements and Sezer, 1982) include:

(2) genitive sg. ip-in ki $z-i $n jyz-yn pul-un genitive pl. ip-ler-in ki $z-lar-i $n jyz-ler-in pul-lar-i $n rope girl face stamp

consonants, and vice versa (though a possible counterexample is proposed by Kaisse, 1992). Nor does the feature [sonorant] assimilate, except as a byproduct of nasal assimilation or complete assimilation. The sequence [dr], for example, does not become [lr]. Stress does not assimilate. An unstressed syllable adjacent to a stressed syllable does not become stressed rather the opposite: two adjacent stressed syllables or two adjacent unstressed syllables are avoided.

Assimilation and Phonological Theory

If linguistic theory is concerned with the question of What is a possible human language? then phonological theory must be concerned with the question of What is a possible process of assimilation? The best theory would be powerful enough to encode all actually occurring assimilatory patterns, but constrained enough to rule out impossible patterns.

Feature-Changing Rules

In many West African languages, all vowels in a word must agree in the feature [advanced (or retracted) tongue root] (Welmers, 1973; Archangeli and Pulleyblank, 1989, Zsiga, 1997). In Igbo, [O-SIala] s/he has told contains only vowels from the retracted set, [o-si-ele] s/he has cooked has vowels only from the advanced set. Several Austronesian languages exhibit long-distance nasal harmony. Nasal assimilation in Sundanese (Robins, 1957; Cohn, 1990) may extend over a sequence of vowels and glides: [Ja a n] wet. Rose and Walker (2004) discuss nasal harmony from consonant to consonant in Kikongo (Kango): [m-bud-idi] I hit, [tu-kun-ini] we planted. Consonant harmony such as that seen in Kikongo is less common than vowel harmony. Attested cases involve long-distance assimilation of nasality, laryngeal features, and subsidiary place features such as [retroflex] or [anterior] (Hansson, 2001; Rose and Walker, 2004). One well-known example is anterior assimilation in Chumash (Poser, 1982): all coronal fricatives and affricates in a word must agree with the rightmost fricative or affricate in the value of [/anterior]: [k-sunon-us] I obey him, [k-sunon-s] I am obedient. Finally, tone may assimilate from vowel to vowel, or syllable to syllable. In Shona, for example, a string of suffixes following a low toned root will be low toned ([e ` re ` Ng] read, [ku ` re ` Ng-e ` s-e ` r-a ` ] to make read -e to) and a string of suffixes following a high-toned root will be high toned ([te Ng] buy, [ku Ng-e s-e r-a ] -te to sell to) (Myers, 1990; Kenstowicz, 1994). The long-distance behavior of tone was instrumental in the development of the theory of autosegmental phonology (Goldsmith, 1976, discussed below).

Some Assimilations That Do Not Occur

In the formal theory of Chomsky and Halle (1968), processes of assimilation were expressed as feature changing rules of the form A ! B/ C D (A changes to B in the context of CAD). The crucial concept of feature matching in assimilation was expressed via alpha notation. Greek letters stand for variables over and , and every instance of the variable in a rule must be filled in with the same value. Thus

(3) [-sonorant] ! [avoice]/ [-sonorant, avoice]

would be read an obstruent agrees in voicing with a following obstruent. The Catalan nasal assimilation rule in (1) above would be:

(4) [nasal] ! [a coronal]/ [b anterior] [g labial] [d back] [E high] [f distributed] [a coronal] [b anterior] [g labial] [d back] [E high] [f distributed]

Feature-changing rules, however, are both too powerful, and not powerful enough (Bach, 1968; Anderson, 1985). They are too powerful in that nothing rules out impossible rules like that in (5):

(5) [-sonorant] ! [avoice] / [-sonorant, aback]

The feature [/-consonantal] does not assimilate. Vowels adjacent to consonants do not become

In this rule, a consonants voicing value must match its feature for back, yet this impossible rule is identical in formal complexity to the common rule of obstruent voicing assimilation. Feature-changing rules are not powerful enough, however, in that the

556 Assimilation

common and straightforward process of nasal place assimilation is represented via a complicated formula.

Feature-Spreading Rules

nonrepresentational account of feature classes in assimilation.

Constraints

In the theory of autosegmental phonology, assimilation is formalized as feature spreading. A feature is linked to a segment via an association line, and features may spread (assimilate) via the addition of further associations. Obstruent voicing assimilation would be formalized as in (6).

(6)

The voicing feature begins as a property of the second consonant in the cluster (indicated by the solid line), but comes to be shared between the two (indicated by the addition of the dotted line). Thus assimilation is given a privileged status as an elementary operation, while more complicated feature switches have a correspondingly more complicated representation. Longdistance assimilation is easily handled as spreading over longer domains. The features [sonorant] and [consonantal] form the core of the segment, the root node, and do not themselves spread. Different hierarchical groupings of autosegmental features (feature geometries) have been proposed to account for the fact that certain groups of features (such as the place features in Catalan or the laryngeal features in Greek) assimilate together (Clements, 1985). If all of the place features are grouped under a single node, then place assimilation can be formalized as the addition of a single association line, the formal simplicity mirroring the rules ubiquity.

(7)

In a nonderivational constraint-based theory such as optimality theory (Prince and Smolensky, 2004), there is no reference to rules or processes of assimilation. Rather, markedness constraints, which define preferred and dispreferred linguistic structures, are argued to prefer sequences where features agree, or where features spread over a certain domain. Such constraints may be grounded in either ease of articulation (e.g., switching voicing in the middle of an obstruent cluster is hard) or ease of perception (e.g., cues to place of articulation in preconsonantal nasals are hard to hear.) Specific assimilations are seen in languages that give specific markedness constraints high priority, and are not seen in languages that give higher priority to maintaining underlying specifications. Kaun (1995), Beckman (1998), and Bakovic (2000) provide constraint-based accounts of vowel harmony. Lombardi (1999) discusses voicing assimilation, and Padgett (1995) provides an account of nasal place assimilation. McCarthy (2004) provides a critical review of ALIGN and SPREAD constraints, and proposes an alternative analysis.

Assimilation vs. Co-articulation

Phonological assimilation can be distinguished from phonetic co-articulation. Daniel Jones, in his Outline of English phonetics (1940), distinguished assimilation, which he defined as a change in phonemic status, and similitude, in which two sounds become more alike but do not change their phonemic identity. In the foregoing discussion, it has been assumed that phonological assimilation results in a change in a segments phonological features (from [voice] to [voice], for example), and thus the segments phonological category. In co-articulation, there is no change in phonological category, but only in phonetic realization. Two articulatory gestures overlap in time, and thus may exert a physical influence on one another. For example, the [k] in key is pronounced further forward than the [k] in coo, because the former is overlapped in time (coarticulated) with a front vowel and the latter is coarticulated with a back vowel. In English, vowels are nasalized before a nasal consonant, because the velum begins to open before closure for the consonant is achieved (Cohn, 1990). Phonological assimilation is complete and categorical; phonetic coarticulation may be gradient and variable (Keating, 1990).

Consensus has not been reached, however, on a universal geometry that can capture all the relevant groupings needed. Harmony systems such as Turkish, where [back] and [round] (but not other vowel features) spread together, have proven problematic. Another challenge is accounting for the fact that consonants are sometimes transparent to vowel assimilations (as in vowel harmony), and sometimes participate in vowel assimilations (as in palatalization). McCarthy (1988), gave an overview of one widely accepted geometry. Hume (1992) and Clements (1993) suggested a different set of class nodes, and Padgett (1995) provided an alternative,

Assimilation 557

It may sometimes be difficult, however, to empirically distinguish the two. Browman and Goldstein (1990, 1992), in the theory of articulatory phonology, showed that overlap and blending of articulatory gestures can result in apparently complete assimilation without any change of phonological features. They argue that in phrases like hundre[b] pounds and i[m] pairs the word-final coronal is still articulatorily present, as shown by phonetic imaging techniques. Assimilation is perceived because a coronal and a labial pronounced at the same time sound like an assimilated labial. Assimilation of alveolar [n] to dental [y], as in the pronunciation of ten things in English, or in the Catalan case discussed above, can also be accounted for in terms of articulatory overlap, as two different overlapping gestures blend to an intermediate place of articulation. Articulatory phonology argues that all assimilations can be accounted for in terms of gestural overlap. Studies such as Cohn (1990) and Zsiga (1995, 1997), however, showed that categorical and gradient processes of assimilation must be distinguished. Cohn (1990) described both gradient and categorical processes of nasal assimilation. Zsiga (1995) showed that the categorical assimilation of [s] to [s] in pressure is qualitatively and quantitatively different from the partial and gradient change in the phrase press your point. Zsiga (1997) examined Igbo [ATR] vowel harmony and vowel assimilation, showing that harmony is categorical and featural, while assimilation (except in some very common phrases like [nwoka-a] from [nwoke-a]) is gradient and the result of gestural overlap. It is argued that phonological features may be mapped into articulatory gestures, but that the phonological and phonetic modules should remain separate.

apparent action-at-a-distance can be reanalyzed, and all assimilation be constrained to be strictly local.

Conclusion

Assimilation is the most common of all phonological processes, and thus has played an important role in phonological theory. Phonological theories have sought to capture what sorts of assimilation can and cannot occur, what groups of features assimilate together, and why certain segments participate in assimilations while others do not. Current work on assimilation is teasing apart the contributions of articulatory coarticulation and phonological feature switch, and continues to examine the proper formalization of local and long-distance assimilations.

See also: Dissimilation; Harmony; Hungarian: Phonology; Phonology: Optimality Theory.

Bibliography

Anderson S (1985). Phonology in the twentieth century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Archangeli D & Pulleyblank D (1989). Yoruba vowel harmony. Linguistic Inquiry 20, 173217. Bach E (1968). Two proposals concerning the simplicity metric in phonology. Glossa 2, 128149. Bakovic E (2000). Harmony, dominance, and control. Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers University. Beckman J (1998). Positional faithfulness. Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Browman C & Goldstein L (1990). Tiers in articulatory phonology, with some implications for casual speech. In Kingston J & Beckman M (eds.) Between the grammar and physics of speech. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 341376. Browman C & Goldstein L (1992). Articulatory phonology: an overview. Phonetics 49, 155180. Chomsky N & Halle M (1968). The sound pattern of English. New York: Harper & Row. Clements G N (1985). The geometry of phonological features. Phonology Yearbook 2, 225252. Clements G N (1993). Lieu darticulation des consonnes et de des voyelles: une the orie unifie e. In Laks B & Rialland A (eds.) LArchitecture et la geometrie des repre sentations phonologiques. Paris: CNRS. Clements G N & Sezer E (1982). Vowel and consonant disharmony in Turkish. In van der Hulst & Smith (eds.). 213255. Cohn A (1990). Phonetic and phonological rules of nasalization. Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles. Gafos A (1999). The articulatory basis of locality in phonology. New York: Garland. Goldsmith J (1976). Autosegmental phonology. Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Is All Assimilation Local Assimilation?

Articulatory phonology has been extended to account for vowel harmony and other long-distance assimilations. Gafos (1999) proposed that harmonizing features should be understood as a single underlying gesture that persists throughout a word. Consonants do not break up sequences of harmonizing vowels, for example, but are overlaid on contiguous vowel gestures. From this point of view, all assimilation is local assimilation. Transparent segments (vowels and consonants that intervene in a harmony domain but that apparently do not share the harmonizing feature) are obviously a problem for this approach. N Chiosa in and Padgett (2001) and Rose and Walker (2004) suggested various means by which such

558 Assimilation Goldsmith J (1985). Vowel harmony in Khalka Mongolian, Yaka, Finnish, and Hungarian. Phonology 2, 253275. Hansson G (2001). Theoretical and typological issues in consonant harmony. Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Berkeley. Hayes B (1999). Phonetically-driven phonology: the role of optimality theory and inductive grounding. In Darnell M, Moravscik E, Noonan M, Newmeyer R & Wheatley K (eds.) Functionalism and formalism in phonology 1: General papers. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 243285. Hume E (1992). Front vowels, coronal consonants, and their interaction in nonlinear phonology. Doctoral dissertation, Cornell University. Ito J (1998). Syllable theory in prosodic phonology. New York: Garland. Jakobson R (1978). Mutual assimilation of Russian voiced and voiceless consonants. Studia Linguistica 32, 107110. Jones D (1940). An outline of English phonetics. New York: Dutton. Kaisse E (1992). Can [consonantal] spread? Language 68, 313332. Kaun A (1995). The typology of rounding harmony: an optimality theoretic approach. Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles. Keating P (1990). Phonetic representation in a generative grammar. Journal of Phonetics 18, 321334. Kenstowicz M (1994). Phonology in generative grammar. Oxford: Blackwell. Kiparsky P (1985). Some consequences of lexical phonology. Phonology Yearbook 2, 83138. Lombardi L (1999). Positional faithfulness and voicing assimilation in optimality theory. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 17, 267302. McCarthy J (1988). Feature geometry and dependency: a review. Phonetica 43, 84108. McCarthy J (2004). Headed spans and autosegmental spreading. MS., University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Myers S (1990). Tone and the structure of words in Shona. New York: Garland. N Chiosa in M & Padgett J (2001). Markedness, segment realization, and locality in spreading. In Lombardi L (ed.) Segmental phonology in optimality theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Padgett J (1995). Partial class behavior and nasal place assimilation. In Proceedings of the 1995 Southwestern Workshop on Optimality Theory. Tucson: University of Arizona. Pater J (1999). Austronesian nasal substitution and other NC effects. In Kager R, van der Hulst H & Zonneveld W (eds.) The prosodymorphology interface. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 310343. Piggott G (1992). Variability in feature dependency: the case of nasality. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 10, 3378. Poser W (1982). Phonological representations and action at a distance. In van der Hulst & Smith (eds.). 121158. Prince A & Smolensky P (2004). Optimality theory: constraint interaction in generative grammar. Oxford: Blackwell. Ringen C (1988). Transparency in Hungarian vowel harmony. Phonology 5, 327342. Robins R H (1957). Vowel nasality in Sundanese: a phonological and grammatical study. In Studies in Linguistic Analysis. Oxford: Blackwell. 87103. Rose S & Walker R (2004). A typology of consonant agreement as correspondence. Language 80(3), 475531. Smyth H W (1920). Greek grammar. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Steriade D (2001). Directional asymmetries in place assimilation: a perceptual account. In Hume B & Johnson K (eds.) The role of speech perception in phonology. New York: Academic Press. 219250. Tsuchida A (1996). Phonetic and phonological vowel devoicing in Japanese. Doctoral dissertation, Cornell University. Vago R (1976). Theoretical implications of Hungarian vowel harmony. Linguistic Inquiry 7, 243263. van der Hulst H & Smith N (eds.) (1982). The structure of phonological representations. Dordrecht: Foris. van der Hulst H & van de Weijer J (1995). Vowel harmony. In Goldsmith J (ed.) The handbook of phonological theory. Oxford: Blackwell. 495534. Walker R (1998). Nasalization, neutral segments, and opacity effects. Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Santa Cruz. Welmers W (1973). African language structures. Berkeley: University of California Press. Zsiga E (1995). An acoustic and electropalatographic study of lexical and post-lexical palatalization in American English. In Connell B & Arvaniti A (eds.) Phonology and phonetic evidence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 282302. Zsiga E (1997). Features, gestures, and Igbo vowels: An approach to the phonologyphonetics interface. Language 73(2), 227274.

You might also like

- PhoneticsDocument68 pagesPhoneticsClaudita Mosquera75% (4)

- Phonemes and Allophones - Minimal PairsDocument5 pagesPhonemes and Allophones - Minimal PairsVictor Rafael Mejía Zepeda EDUCNo ratings yet

- Tpcastt TemplateDocument3 pagesTpcastt TemplateHunte AcademyNo ratings yet

- Reverse Sanskrit DictionaryDocument551 pagesReverse Sanskrit Dictionarysktkoshas100% (1)

- Anejom Grammar SketchDocument62 pagesAnejom Grammar Sketchalexandreq100% (1)

- Learn Greek (3 of 7) - Greek Phonology, Part IDocument20 pagesLearn Greek (3 of 7) - Greek Phonology, Part IBot Psalmerna100% (2)

- English GlobalizationDocument7 pagesEnglish Globalizationdautgh0% (1)

- Understanding diphthongs and triphthongs in English phonologyDocument5 pagesUnderstanding diphthongs and triphthongs in English phonologyHaniza AnyssNo ratings yet

- Correction Symbols GuideDocument1 pageCorrection Symbols GuideGerwilmotNo ratings yet

- A Phoneme As A Unit of PhonologyDocument10 pagesA Phoneme As A Unit of PhonologyqajjajNo ratings yet

- A System For Typesetting Mathematics - Brian W. Kernighan and Lorinda L. CherryDocument7 pagesA System For Typesetting Mathematics - Brian W. Kernighan and Lorinda L. CherrysungodukNo ratings yet

- Communicative ApproachDocument9 pagesCommunicative ApproachAmal OmarNo ratings yet

- Non-Equivalence at Word Level Problems and StrategiesDocument175 pagesNon-Equivalence at Word Level Problems and Strategiesbuzzcockscrass75% (4)

- Pages From FlyHigh - 4 - Fun - Grammar PDFDocument4 pagesPages From FlyHigh - 4 - Fun - Grammar PDFPaul JonesNo ratings yet

- University of California, Berkeley University of Lancaster: The Word in LugandaDocument19 pagesUniversity of California, Berkeley University of Lancaster: The Word in LugandaFrancisco José Da SilvaNo ratings yet

- SUBJECT and OBJECT QUESTIONSDocument4 pagesSUBJECT and OBJECT QUESTIONSBosiljka NovakovicNo ratings yet

- Local Assimilation: Dissimilation Harmony CoalescenceDocument30 pagesLocal Assimilation: Dissimilation Harmony CoalescenceMd SyNo ratings yet

- Assimilation and Some Implications To English Teaching in Faculty of English - HNUEDocument14 pagesAssimilation and Some Implications To English Teaching in Faculty of English - HNUETuan PhamNo ratings yet

- In PhonologyDocument5 pagesIn Phonologyسہۣۗيزار سہۣۗيزارNo ratings yet

- Assimilation of Consonants in English and Assimilation of The Definite Article in ArabicDocument7 pagesAssimilation of Consonants in English and Assimilation of The Definite Article in Arabicابو محمدNo ratings yet

- Iw7xw 9zfzgDocument7 pagesIw7xw 9zfzgicha novita sariNo ratings yet

- Phonology-Distinctive Sound - HandoutDocument4 pagesPhonology-Distinctive Sound - HandoutGusti PutuNo ratings yet

- LING1000 Intro to Language Assignment 1Document5 pagesLING1000 Intro to Language Assignment 1Xiaoyu LiuNo ratings yet

- Terry Crowley: Chapter 2: 2.1 Lenition and FortitionDocument28 pagesTerry Crowley: Chapter 2: 2.1 Lenition and FortitionNazwa MustikaNo ratings yet

- English Phonemes and English AlphabetsDocument8 pagesEnglish Phonemes and English AlphabetsGigih Aji PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- The System of The English PhonemesDocument25 pagesThe System of The English PhonemesАлександра КулиничNo ratings yet

- Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis: Insight Into Pronunciation Errors of Igala Learners of EnglishDocument10 pagesContrastive Analysis Hypothesis: Insight Into Pronunciation Errors of Igala Learners of EnglishTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- English Phonological Problems Encountered by Buginese Learners Gusri Emiyati Ali, S.PD., M.PDDocument8 pagesEnglish Phonological Problems Encountered by Buginese Learners Gusri Emiyati Ali, S.PD., M.PDrafika nur dzakiraNo ratings yet

- Linguistics: Introduction To Phonetics and PhonologyDocument10 pagesLinguistics: Introduction To Phonetics and PhonologyShweta kashyapNo ratings yet

- Linguistics: Introduction To Phonetics and PhonologyDocument10 pagesLinguistics: Introduction To Phonetics and PhonologySwagata RayNo ratings yet

- Distributions - Group 2 PhonologyDocument19 pagesDistributions - Group 2 PhonologyWindy Astuti Ika SariNo ratings yet

- Sound Change Includes Any Processes of Language Change That Affect PronunciationDocument8 pagesSound Change Includes Any Processes of Language Change That Affect PronunciationGede Agus ArtasthanaNo ratings yet

- Dr Eman Alhusaiyan's English Phonology Course (NGL 422Document18 pagesDr Eman Alhusaiyan's English Phonology Course (NGL 422Dr.Eman LinguisticsNo ratings yet

- Phonology: The Sound Patterns of Language: Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) A High School StudentDocument57 pagesPhonology: The Sound Patterns of Language: Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) A High School StudentAnonymous i437GuqkT4No ratings yet

- Oral English As An Aid To Learning in Higher Institutions in NigeriaDocument7 pagesOral English As An Aid To Learning in Higher Institutions in NigeriaOFONDU MATTHEWNo ratings yet

- English Grammar and WritingDocument35 pagesEnglish Grammar and WritingDhivyaNo ratings yet

- AshbyspokenDocument7 pagesAshbyspokenNafiseh Sadat MirfattahNo ratings yet

- A Handbook On English Grammar and WritingDocument36 pagesA Handbook On English Grammar and WritingSagar KathiriyaNo ratings yet

- 2 PhonologyDocument10 pages2 PhonologyNaoufal FouadNo ratings yet

- WORKSHEET 3 Sound Change WorkedDocument6 pagesWORKSHEET 3 Sound Change WorkedNicolás CaresaniNo ratings yet

- The SyllableDocument10 pagesThe Syllableسہۣۗيزار سہۣۗيزارNo ratings yet

- Фонетика сессияDocument8 pagesФонетика сессияAluaNo ratings yet

- Chp.2 Introducing PhonologyDocument8 pagesChp.2 Introducing PhonologySaif Ur RahmanNo ratings yet

- CONSONANTSDocument6 pagesCONSONANTSnadia nur ainiNo ratings yet

- End-Of-Term Assignment: Cognitive LinguisticsDocument12 pagesEnd-Of-Term Assignment: Cognitive LinguisticsLoc NguyenNo ratings yet

- 6 ФОНЕТИКАDocument7 pages6 ФОНЕТИКАВиктория ДмитренкоNo ratings yet

- Meeting 2 - Language and SoundsDocument37 pagesMeeting 2 - Language and SoundsSommerled100% (1)

- Teaching Vowels PhysicallyDocument11 pagesTeaching Vowels PhysicallyMuhammad WaqasNo ratings yet

- Linguistics Reading 2Document11 pagesLinguistics Reading 2AlexahaleNo ratings yet

- 3 - M28 - S5P2, Phonetics & Phonology, Last Courses, Pr. TounsiDocument18 pages3 - M28 - S5P2, Phonetics & Phonology, Last Courses, Pr. TounsiCHARROU Mohamed AminENo ratings yet

- Cardinal Vowels 1Document2 pagesCardinal Vowels 1Anam AkramNo ratings yet

- 1 Vowels - Yule, 2010Document2 pages1 Vowels - Yule, 2010Roberto Carlos Sosa BadilloNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7-The Phoneme Feb 08Document19 pagesChapter 7-The Phoneme Feb 08Aci Sulthanal KhairatiNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Tongue Slips and The Field of Linguistics Zaynab Abbudi Ali (M. A)Document11 pagesThe Relationship Between Tongue Slips and The Field of Linguistics Zaynab Abbudi Ali (M. A)محمد ناصر عليويNo ratings yet

- Articulatory and Functional Aspects of English Speech Sounds (39Document8 pagesArticulatory and Functional Aspects of English Speech Sounds (39Вика СелюкNo ratings yet

- Megyesi Hungarian PDFDocument14 pagesMegyesi Hungarian PDFOreg NeneNo ratings yet

- Study of Language AssignmentDocument6 pagesStudy of Language Assignmentankit dubeyNo ratings yet

- 2nd AssignmentDocument4 pages2nd AssignmentFlorencia GossioNo ratings yet

- English Plosives and AssimilationDocument2 pagesEnglish Plosives and AssimilationRekar FazilNo ratings yet

- AEN2121 NOTE2- PHONOLOGY (Autosaved)Document53 pagesAEN2121 NOTE2- PHONOLOGY (Autosaved)mutheukaren4No ratings yet

- Articulators Above The LarynxDocument23 pagesArticulators Above The LarynxHilmiNo ratings yet

- Chp.10 Syllable Complexity (M Naveed)Document7 pagesChp.10 Syllable Complexity (M Naveed)Saif Ur RahmanNo ratings yet

- English Phonology M2Document10 pagesEnglish Phonology M2wanda wulanNo ratings yet

- Examples and Observations: EtymologyDocument8 pagesExamples and Observations: EtymologyDessy FitriyaniNo ratings yet

- The Etymology and Syntax of the English Language: Explained and IllustratedFrom EverandThe Etymology and Syntax of the English Language: Explained and IllustratedNo ratings yet

- Brain damage leads to sign language disordersDocument4 pagesBrain damage leads to sign language disordersjoagvidoNo ratings yet

- Language - The Language Barrier - Nature News"Document9 pagesLanguage - The Language Barrier - Nature News"joagvidoNo ratings yet

- Il 01Document12 pagesIl 01joagvidoNo ratings yet

- Sonority Constraints On Onset-Rime Cohesion - Evidence From Native and Bilingual Filipino Readers of English Alonzo Taft 2002Document16 pagesSonority Constraints On Onset-Rime Cohesion - Evidence From Native and Bilingual Filipino Readers of English Alonzo Taft 2002joagvidoNo ratings yet

- LSA Frequency of Consonant ClustersDocument7 pagesLSA Frequency of Consonant ClustersjoagvidoNo ratings yet

- Cultural Cognition Programs Fit Human BrainDocument17 pagesCultural Cognition Programs Fit Human BrainCarolina ChabelaNo ratings yet

- Perilus XIII Phonetics Engstrand Et Al 1991Document172 pagesPerilus XIII Phonetics Engstrand Et Al 1991joagvidoNo ratings yet

- Google Wave - Tutorial: Vogella - deDocument9 pagesGoogle Wave - Tutorial: Vogella - dejoagvidoNo ratings yet

- Short Reflection Papers RubricDocument2 pagesShort Reflection Papers RubricMylleNo ratings yet

- Speech RubricsDocument1 pageSpeech RubricsMae ZenNo ratings yet

- CEFR LevelsDocument2 pagesCEFR LevelsLiterature92No ratings yet

- Problems of Education in The 21st Century, Vol. 27, 2011Document125 pagesProblems of Education in The 21st Century, Vol. 27, 2011Scientia Socialis, Ltd.No ratings yet

- The Internet TESL JournalDocument4 pagesThe Internet TESL JournalWilson NavaNo ratings yet

- Score: Preliminary Examination 1 Semester SY 2021-2022 English Enhancement (ENG100)Document3 pagesScore: Preliminary Examination 1 Semester SY 2021-2022 English Enhancement (ENG100)Argus MagalingNo ratings yet

- Grammar Book - Intro To Biblical Greek (Unicode)Document91 pagesGrammar Book - Intro To Biblical Greek (Unicode)Rica MhonttNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1-Types of Islamic Texts and Their Characteristics-Translation of Proper NamesDocument11 pagesLecture 1-Types of Islamic Texts and Their Characteristics-Translation of Proper Namesyoshi hiNo ratings yet

- Demo PrintDocument18 pagesDemo PrintHazel L. ansulaNo ratings yet

- 76 - Interviewing For A Job - Low Int - CanDocument11 pages76 - Interviewing For A Job - Low Int - CanGiancarlo PereiraNo ratings yet

- Demo Grade 34 Word Work Worksheets Ontario Curriculum 5696988Document9 pagesDemo Grade 34 Word Work Worksheets Ontario Curriculum 5696988Jay BlackwoodNo ratings yet

- RolltheDice Racing VocabularyDocument5 pagesRolltheDice Racing VocabularyRosa VuNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1Document5 pagesLesson 1Omar ShahidNo ratings yet

- Q2 English DLL Day Week 8Document5 pagesQ2 English DLL Day Week 8Mafey DadivasNo ratings yet

- Matching Headings Questions Strategy PracticeDocument5 pagesMatching Headings Questions Strategy PracticeSabzali NavruzovNo ratings yet

- Katrenalen K. Homonyms LPDocument4 pagesKatrenalen K. Homonyms LPPrincess Mikee JamasaliNo ratings yet

- Social Contexts of SLADocument26 pagesSocial Contexts of SLAMesa BONo ratings yet

- Cravings EssayDocument2 pagesCravings EssayLex PendletonNo ratings yet

- Grammar Section - Past SimpleDocument1 pageGrammar Section - Past SimpleFrancisco José Valero FernándezNo ratings yet

- Affixation AnalysisDocument13 pagesAffixation AnalysisMoh'd Kalis KapinaNo ratings yet

- Formal Languages and Their Relation To AutomataDocument262 pagesFormal Languages and Their Relation To AutomataAashaya MysuruNo ratings yet