Professional Documents

Culture Documents

CFD Assignment Final

Uploaded by

djtj89Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

CFD Assignment Final

Uploaded by

djtj89Copyright:

Available Formats

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

CFD ASSIGNMENT

NUMERICAL SIMULATION OF FLUID FLOW AND HEAT TRANSFER

MIHIR MEETARBHAN

0922031

08/12/11

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

PROBLEM UNDER INVESTIGATION

The problem being investigated is the steady flow of air, which is viscous and incompressible (i.e., constant density), through a duct which has a heated plate midway through its lower part. The duct also has an elbow which is at 35 just after the hot flat plate. The study is being carried out in order to investigate the formation of boundary layers at the wall of the duct and the heat transfer taking place between the hot plate and the working fluid. When air enters the duct, it comes into contact with the walls of the duct. As the walls are not smooth, there is friction between the air flow and the walls. Hence this causes the particles of air close to the wall to slow down. As this occurs, the faster layer of air above collides with the slower particles and form a boundary layer. This is a slow moving layer of air where the velocity is zero close to the wall. The following are the operating conditions of the fluid flow in the duct: U (m/s) = Air velocity T (C) = Air temperature Tw (C) = Flat plate wall temperature L1 (m) = Length of duct bend (lower wall) L2 (m) = Length of flat plate L3 (m) = Length of duct before bend L4 (m) = Length of duct after bend H1 (m) = Duct height H2 (m) = Distance between the flat plate and lower duct wall () = Bend sudtended angle The problem was investigated using the Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) approach. The RANS equations are used to describe turbulent flows. These equations can be used with approximations based on knowledge of the properties of flow turbulence to give approximate time-averaged solutions. The assumption (known as the Reynolds decomposition) behind the RANS equations is that the time-dependent turbulent (chaotic) velocity fluctuations can be separated from the mean flow velocity. This transform then introduces a set of unknowns called the Reynolds stresses, which are functions of the velocity fluctuations, and which require a turbulence model (e.g., the two-equation k-epsilon model) to produce a closed system of solvable equations. The reduced computational requirements for the RANS equations, while still significant, are orders of magnitude less than that required for the original Navier-Stokes equations. Another advantage of using the RANS equations for steady fluid flow simulation is that the mean flow velocity is calculated as a direct result without the need to average the instantaneous velocity over a series of time steps. The CFD model, as shown in figure , was created using the software GAMBIT. The model was divided into 12 different faces. This was done in order to ensure that the meshing of each part of the model was done accurately. The faces numbers (before and after plate) had 30 meshes vertically and 40 meshes horizontally with a ratio of 1.2. This ensured that the mesh was fine enough at the walls in order to obtain an simulation of the boundary layers near the walls of the duct. Faces numbers (just on plate) had 15 meshes vertically and 40 meshes horizontally with a double sided ratio of 1.2. This was done so as to obtain fine meshes near the walls of the duct and near the flat plate so that boundary layers could be analysed accurately and accurate y+ values could be obtained. 2

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

BOUNDARY CONDITIONS 1. Inlet At the inlet, a velocity inlet boundary condition was applied and the velocity components were also specified x = 9 m/s. The temperature of the air was also set to 29C (302K). Turbulence intensity and hydraulic diameter were set to 1% and 0.5m respectively. As the flow being investigated is a flow in a pipe with low Reynolds number, the turbulence intensity is set to a relatively low value as there will be a medium of turbulence in the flow. Hydraulic diameter was used as the flow is a fully developed wall bounded flow. Hence the real diameter of the duct was used for the hydraulic diameter.

2. Wall At the wall, a wall boundary condition was set. This was set in order for the flow to be a wall bounded flow. This would then enable the boundary layers close to the wall to be studied. The wall has a roughness constant of 0.5 and a temperature of 300 k. 3. Outlet At the outlet, an outflow boundary condition was applied. 4. Flat Plate The flat plate had the boundary condition of a wall. Its temperature was set to 45 C (318 K) and the material used was aluminium. This boundary condition was set in order to analyse the heat transfer between the plate and the air flowing over it. Moreover, boundary layers forming on it can be studied.

TURBULENCE MODEL For the purpose of this study, the standard k- turbulence model was used where k is the turbulent kinetic energy and is the dissipation rate of the turbulent energy. is the variable that determines the scale of the turbulence, whereas the first variable, k, determines the energy in the turbulence. The use of this turbulence model is to predict the effect of turbulence on the mean flow. This model is a two-equation model meaning that it has two extra equations to represent the turbulent properties of the flow. Hence, this allows the model to account for effects like convection and diffusion of turbulent energy.

DISCRETISATION SCHEMES To account for transient effects, the governing equations must be discretised in time. Transient effects are usually dealt with by using a time stepping procedure, with an initial condition provided. The time dimension is divided into a set of discrete time steps, each of size t. The discretisation schemes used in solving this problem were: 3

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

Pressure standard Momentum second order upwind Turbulent k.e second order upwind Turbulent Dissipation Rate second order upwind Energy second order upwind The second order upwind discretisation scheme was used as this will yield an implicit system of second order accuracy with the extra storage of one additional time step meaning that the solution will be more accurate as compared to that of a first order upwind.

GRID DETAILS The grid used to solve this problem was structured grid. Structured grids have a considerable advantage over other grid methods in that they allow the user a high degree of control. It means that it enables the user to easily identify and efficiently access any point on the grid which allows for faster CFD codes. These types of grids utilize quadrilateral elements in 2D in a computationally rectangular array. Hence this enables the user to concentrate grid lines in regions where boundary layers and vortices are likely to occur and reduce the number of grid lines in regions where no major change in flow pattern take place. CONVERGENCE CRITERIA The convergence process is an iterative process which means that values are changing from one iteration to the next. As all numerical solutions contain errors, in order to minimize those errors, residual values are changed. Solver residuals represent the absolute error in the solution of a particular variable. Hence reducing their value give better convergence which in turn give better results. For this problem, the calculation was first performed with normalised residuals and was allowed to converge after 93 iterations. Following that, the residuals were reduced to 10 e-10 and the further iterations were performed in order to allow the solution to converge at 682 iterations, hence obtaining more accurate results.

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

Boundary layer profiles

The Navier-Stokes equation deals with fluid flow which are viscous, compressible and heat conducting. The layer of fluid in which the effects of viscosity and thermal conductivity are important is known as the boundary layer. The law of the wall states that the average velocity of a turbulent flow at a certain point is proportional to the logarithm of the distance from that point to the wall, or the boundary of the fluid region. This law applies particularly to parts of the flow that are very close to the wall. Those are the regions where boundary layers are more likely to be produced. The log law states that: where

Figures show the lines set at different locations in the duct in order to analyse the boundary layer formations taking place on the lower wall of the duct according to the law of the wall. Figure shows the u+ vs y+ boundary layer profiles for the three lines placed before the plate. From figure , we can see that for Y+ values less than 10^3, the profiles follow the log law for a range of Y+ values. As the log law only applies to parts of the flow that are very close to the wall, i.e. 20% of the height of the flow, after Y+ values greater than 10^3, the profiles tend to deviate away from the log law as the ducts centerline is approached. This is so because close to the wall of the duct, the velocity tends to zero due to boundary layer formation. Hence, while approaching the ducts centerline, the log law no longer applies as the height of the flow is above 20% at the ducts centerline, the average velocity increases, thus giving rise to the divergence in the u+ v/s y+ plots. Figure show the u+ vs y+ boundary layer profiles for three lines placed at the bend. For these plots, the profiles tend to follow the log law for greater values of y+. This is so because at the 5

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

bend, the boundary layer is a lot thicker than before the bend. Hence there is a greater y-distance from the wall where the velocity is relatively low. After that region, where the log law no longer applies, the velocity increases as the duct centerline is approached. At that point, the u+ vs y+ profiles deviates slightly from the log law. Vector plot of the velocity field Figure show the vector plot of the velocity field on the plate. The vector plot is colour coded according to the velocity magnitude. From the plot we can see that close to the wall, the velocity tends to be zero due to the no slip boundary condition at the wall. The no slip condition for viscous flow states that at a solid boundary, the fluid will have zero velocity relative to the boundary. This is so because at the wall, the particles of the fluid tend to stick to the wall, hence creating a boundary layer. According to boundary layer equations, the flow velocity then increases rapidly within the boundary layer as shown in figure . Downstream of the leading edge of the plate, the flow is uniform and has no vorticity except in a narrow region adjacent to the plate. This narrow region containing vorticity is the viscous boundary layer. The thickness of the boundary layer increases along the length of the plate. Fluid deceleration is transferred successively from one fluid layer to the next by viscous shear stresses acting in the layers. Figure , compares the velocity profiles upstream and downstream along the plate. The velocity gradient at the wall is less downstream than upstream, indicating that the wall shear stress decreases along the plate. Temperature and Turbulence Kinetic Energy Figure , shows the variation of temperature with the distance normal to the lower wall of the duct at several locations downstream of the plate trailing edge. The graph shows that the temperature throughout the duct tends to remain constant except in the region downstream of the plate trailing edge. The highest temperature is found closer to the plate and as we move downstream, the temperature gets dissipated. This is because the highest amount of heat transfer takes place in the region close to the plate. Figure , shows the variation of turbulence k.e with the distance normal to the lower wall of the duct at several locations downstream of the plate trailing edge. The largest amount of turbulence k.e occurs at the trailing edge of the flat plate. As the boundary layer develops over the plate, the flow slowly turns turbulent. This is called boundary layer transition. Variation of friction coefficient on lower wall

Rate of Heat Transfer from the Flat Plate As air flows over the flat plate, thermal energy is transferred to the air by means of convection. As the plate is hotter than the air, a temperature gradient is formed between the two media. This gives rise to heat transfer between the air and the plate. From the temperature plot (figure), we can see that more heat transfer takes place above the flat 6

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

plate than below it. This is because the velocity of the air above the plate is higher than that below it. This is the case as The heat transfer from a hot plate to a laminar air stream is calculated by FLUENT using Newtons law:

Where

is the rate of heat transfer,

is the convection heat transfer coefficient, is the air temperature.

is the

area of the plate,

is the wall temperature and

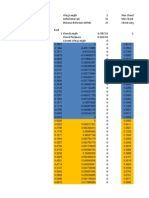

Total Heat Transfer Rate (W) -------------------------------- -------------------Heated plate 323.95258 Heated plate shadow 301.66336 ---------------- -------------------Net 625.61594 The heat transfer data from FLUENT shows that the plate transfers 625.62 W of heat to the air flowing over it. Pressure loss between Inlet and Outlet The total pressure data between the inlet and the outlet by FLUENT: Total Pressure (pascal)(m2) -------------------------------- -------------------Inlet 25.310217 Outlet 22.634186 ---------------- -------------------Net 47.944405 FLUENT calculates the pressure drop by taking into consideration Reynolds number, pipe relative roughness, flow velocity, density of fluid and the dynamic viscosity of the fluid. For the flow in a pipe, Reynolds number: Re = v where v is the mean velocity of the object relative to the fluid, DH is the hydraulic diameter of the pipe and v is the kinematic viscosity. This states that there is a pressure drop of 2.676 Pa between the inlet and the outlet. The pressure drop in the pipe is a result of frictional forces acting on the fluid as it flows through the duct. The frictional forces are caused by a resistance to flow due to the fluid viscosity. Pressure drop is proportional to the frictional shear forces in the duct. Hence, the higher the wall roughness in the duct, the higher the pressure drop. 7

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

Pressure drop also occurs due to change in height of the duct and parasitic drag. Parasitic drag consists of form drag and skin friction drag. Those are the two types of drag that arise in the duct. Skin friction drag takes place as the wall has a certain roughness and is caused by the actual contact of the air particles against the walls of the duct. Pressure drag arises because of the shape of the object. As the duct has a flat plate midway through it and also as it has a 35 bend, those are contributing factors to the form drag. As air flows over the plate, a boundary layer is formed. Eventually the air tends to separate thus creating a wake hence opposing forward flow motion which in turn causes drag. Parasite Drag = Form Drag + Skin Friction Drag The two types of drag mentioned above follow the drag equation:

Where fluid,

is the force of drag, is the fluid density, v is the speed of the object relative to the is the drag coefficient and A is the reference area.

Frictional Drag on the flat plate

Reynolds number = Coefficient of drag ( Reference area = 1 Hence the frictional drag of the flat plate = ) = 0.001

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

APPENDIX

CFD model

Figure 1. CFD model with dimensions Duct with Investigation lines

Figure 2. Duct with lines to investigate several parameters a) b) c) d) e) f) g) h) i) j) k) Line 1 bottom Line 2 bottom Line 3 bottom Line before plate Midway plate End of plate Midway curve End of curve Line 1 top Line 2 top Line 3 top

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

Mesh From GAMBIT (Numbered faces)

Figure 3. Mesh from GAMBIT showing face numbers Turbulence Profile

Figure 4. Contours plot showing turbulence

10

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

Boundary layer profiles

Line 1 Bottom U+ vs Y+

3.00E+01 2.50E+01 2.00E+01 U+ 1.50E+01 1.00E+01 5.00E+00 0.00E+00 1.00E+00 U+ U+ theoretical

1.00E+01

1.00E+02 Y+

1.00E+03

1.00E+04

Line 2 Bottom U+ vs Y+

3.00E+01 2.50E+01 2.00E+01 U+ 1.50E+01 1.00E+01 5.00E+00 0.00E+00 1.00E+00 U+ U+ Theoretical

1.00E+01

1.00E+02 Y+

1.00E+03

1.00E+04

11

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

Line 3 Bottom U+ vs Y+

3.00E+01 2.50E+01 2.00E+01 U+ 1.50E+01 1.00E+01 5.00E+00 0.00E+00 1.00E+00 U+ U+ theoretical

1.00E+01

1.00E+02 Y+

1.00E+03

1.00E+04

Line before plate U+ vs Y+

3.00E+01 2.50E+01 2.00E+01 U+ 1.50E+01 1.00E+01 5.00E+00 0.00E+00 1.00E+00

U+ U+ theoretical

1.00E+01

1.00E+02 Y+

1.00E+03

1.00E+04

12

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

Midway Plate U+ vs Y+

3.00E+01 2.50E+01 2.00E+01 U+ 1.50E+01 1.00E+01 5.00E+00 0.00E+00 1.00E+00 U+ U+ theoretical

1.00E+01

1.00E+02 Y+

1.00E+03

1.00E+04

End of Plate U+ vs Y+

3.00E+01 2.50E+01 2.00E+01 U+ 1.50E+01 1.00E+01 5.00E+00 0.00E+00 1.00E+00 U+ U+ thoretical

1.00E+01

1.00E+02 Y+

1.00E+03

1.00E+04

13

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

Midway curve U+ vs Magnitude Y+

3.00E+01 2.50E+01 2.00E+01 1.50E+01 1.00E+01 5.00E+00 0.00E+00 1.00E+00 U+ U+ theoretical

Axis Title

1.00E+01

1.00E+02

1.00E+03

1.00E+04

Magnitude Y+

End of Curve U+ vs Magnitude Y+

3.00E+01 2.50E+01 2.00E+01 Axis Title 1.50E+01 1.00E+01 5.00E+00 0.00E+00 1.00E+00

U+ U+ theoretical

1.00E+01

1.00E+02

1.00E+03

1.00E+04

Magnitude Y+

14

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

Line 1 Top U+ vs Magnitude Y+

3.00E+01 2.50E+01 Axis Title 2.00E+01 1.50E+01 1.00E+01 5.00E+00 0.00E+00 1.00E+00 U+ U+ theoretical

1.00E+01

1.00E+02

1.00E+03

1.00E+04

Magnitude Y+

Line 2 Top U+ vs Magnitude Y+

3.00E+01 2.50E+01 2.00E+01 Axis Title 1.50E+01 1.00E+01 5.00E+00 0.00E+00 1.00E+00

U+ U+ theoretical

1.00E+01

1.00E+02

1.00E+03

1.00E+04

Magnitude Y+

15

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

Line 3 Top U+ vs Magnitude Y+

3.00E+01 2.50E+01 2.00E+01 Axis Title 1.50E+01 1.00E+01 5.00E+00 0.00E+00 1.00E+00 U+ U+ theoretical

1.00E+01

1.00E+02

1.00E+03

1.00E+04

Magnitude Y+

Line plots of Temperature

Temperature v/s Distance magnitude

3.20E+02 3.18E+02 3.16E+02 3.14E+02 Temperature 3.12E+02 3.10E+02 3.08E+02 3.06E+02 3.04E+02 3.02E+02 3.00E+02 0.00E+00 1.00E-01 2.00E-01 3.00E-01 4.00E-01 Distance Magnitude 5.00E-01 Before end of curve Temp Before midway curve temp End of curve temp End of plate temp Midway curve temp

6.00E-01

Figure 16. Plots showing difference in temperature at different locations in the duct

16

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

Line plots of turbulence kinetic energy

Turbulence K.E v/s Distance magnitude

8.00E-01 7.00E-01 6.00E-01 Turbulence k.e 5.00E-01 4.00E-01 3.00E-01 2.00E-01 1.00E-01 0.00E+00 0.00E+00 1.00E-01 Before end of curve turbulence Before midway curve turbulence End of curve turbulence End of plate turbulence Midway curve turbulence

2.00E-01 3.00E-01 4.00E-01 Distance Magnitude

5.00E-01

6.00E-01

Figure 17. Plots showing variation of turbulence k.e at different locations in the duct Skin Friction coefficient on lower wall

Figure 18. Line plot showing variation in skin friction coefficient along the lower wall of the duct

17

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

Convergence Plots

Figure 19. Plots showing initial convergence with no change in residuals

Figure 20. Diagram showing turbulence plot after initial convergence

18

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

Figure 21. Plots showing second convergence with change in residuals

Figure 22. Diagram showing turbulence plot after initial convergence

Velocity Profile

19

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

Figure 23. Velocity profile of duct

Vector plot of Velocity field

Figure 24. vector plot of velocity field

20

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

Figure 25. Vector plot of velocity field on lower wall of duct before bend

Figure 26. Vector plot of velocity field on plate

21

Mihir Meetarbhan

0922031

Figure 27. Vector plot of velocity field on bend

22

You might also like

- CFD Analysis of Flow Separation on a NACA 0012 FoilDocument4 pagesCFD Analysis of Flow Separation on a NACA 0012 FoilTom FallonNo ratings yet

- CFD Analysis and Optimization of Geometrical Modifications of Ahmed BodyDocument13 pagesCFD Analysis and Optimization of Geometrical Modifications of Ahmed BodyIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Mesh CFDDocument65 pagesMesh CFDPankaj GuptaNo ratings yet

- Serba Dinamik Capabilities in Power PlantDocument11 pagesSerba Dinamik Capabilities in Power PlantThiruvengadamNo ratings yet

- Automotive Aerodynamics Mini-Project On "Aerodynamic Study of A Simplified Light Commercial Vehicle (LCV) With A Modified Trailer Design. "Document12 pagesAutomotive Aerodynamics Mini-Project On "Aerodynamic Study of A Simplified Light Commercial Vehicle (LCV) With A Modified Trailer Design. "Saketh Pemmasani0% (1)

- Progression February March April May Week 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 Preparation and PlanningDocument2 pagesProgression February March April May Week 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 Preparation and PlanningmanorajNo ratings yet

- Proceedings of 2006 WSEAS Conference on Heat and Mass TransferDocument7 pagesProceedings of 2006 WSEAS Conference on Heat and Mass TransferAnonymous knICaxNo ratings yet

- Assignment: CE-203 Fluid MechanicsDocument9 pagesAssignment: CE-203 Fluid MechanicsPawan Niranjan100% (1)

- CEB2063 - Drying of Process Materials - Lecture 1 (Group 1)Document31 pagesCEB2063 - Drying of Process Materials - Lecture 1 (Group 1)Scorpion RoyalNo ratings yet

- Why Do My Recordings Sound Like ASSDocument36 pagesWhy Do My Recordings Sound Like ASSJoilson MoreiraNo ratings yet

- CMMS Report Week#18 Activity MaintenanceDocument6 pagesCMMS Report Week#18 Activity MaintenanceAntoni GultomNo ratings yet

- C.R. Siqueira - 3d Transient Simulation of An Intake Manifold CFD - SAE 2006-01-2633Document7 pagesC.R. Siqueira - 3d Transient Simulation of An Intake Manifold CFD - SAE 2006-01-2633Thomas MouraNo ratings yet

- CFD External Flow Validation For AirfoilDocument14 pagesCFD External Flow Validation For AirfoilertugrulbasesmeNo ratings yet

- Fluid Flow Measurements by Means of Vibration MonitoringDocument12 pagesFluid Flow Measurements by Means of Vibration MonitoringthiagofbbentoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To CF D ModuleDocument46 pagesIntroduction To CF D ModuleResul SahinNo ratings yet

- CAETraining (Fluid)Document129 pagesCAETraining (Fluid)andysarmientoNo ratings yet

- Axial Fan NotchDocument3 pagesAxial Fan NotchhahasiriusNo ratings yet

- Exp 7 - Cavitation (Conclusion)Document1 pageExp 7 - Cavitation (Conclusion)Muhammad FawwazNo ratings yet

- CMMS Implementation RoadmapDocument1 pageCMMS Implementation RoadmapambuenaflorNo ratings yet

- Optimization of Turbo Machinery Validation Against Experimental ResultsDocument13 pagesOptimization of Turbo Machinery Validation Against Experimental ResultsSrinivasNo ratings yet

- Lid Driven Cavity Flow OK Final EldwinDocument33 pagesLid Driven Cavity Flow OK Final Eldwineldwin_dj7216No ratings yet

- Flow Visualization Optical TechniquesDocument21 pagesFlow Visualization Optical TechniquesmgskumarNo ratings yet

- Analysis of A Compessor Rotor Using Finite Element AnalysisDocument21 pagesAnalysis of A Compessor Rotor Using Finite Element Analysisinam vfNo ratings yet

- Lid Driven FlowDocument8 pagesLid Driven Flowmanoj0071991No ratings yet

- Gas Dynamics and Jet PropulsionDocument317 pagesGas Dynamics and Jet PropulsionVinoth RajaguruNo ratings yet

- APD Dynamic StressesDocument11 pagesAPD Dynamic StressesadehriyaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Turbulence ModellingDocument16 pagesIntroduction To Turbulence Modellingknowme73No ratings yet

- CFX-Intro 14.5 WS01 Mixing-TeeDocument48 pagesCFX-Intro 14.5 WS01 Mixing-TeeShaheen S. RatnaniNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 - FEMDocument34 pagesChapter 7 - FEMpaivensolidsnake100% (1)

- IMPACT OF JOB STRESS ON TELECOM EMPLOYEE JOB SATISFACTIONDocument43 pagesIMPACT OF JOB STRESS ON TELECOM EMPLOYEE JOB SATISFACTIONPratya MishraNo ratings yet

- CFD NotesDocument115 pagesCFD NotesKarthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- Ansys Fluent Tutorials - ListDocument12 pagesAnsys Fluent Tutorials - ListAhsan0% (1)

- CFD Manual FluentDocument82 pagesCFD Manual FluenttfemilianNo ratings yet

- Determing Heat Transfer of CansDocument7 pagesDeterming Heat Transfer of CanslongNo ratings yet

- Calculation of Atmosferic Dispersion From StackDocument28 pagesCalculation of Atmosferic Dispersion From Stackgeorge cabreraNo ratings yet

- Create and Customize Your Physical ModelsDocument30 pagesCreate and Customize Your Physical Modelsraul19rsNo ratings yet

- 04 TurbulenceDocument37 pages04 TurbulenceYaroslavBerezhkoNo ratings yet

- Design and CFD Analysis of A Centrifugal Pump: CH .Yadagiri, P.VijayanandDocument15 pagesDesign and CFD Analysis of A Centrifugal Pump: CH .Yadagiri, P.VijayanandFarshidNo ratings yet

- Analysis of A Failed Pipe Elbow in Geothermal Production Facility PDFDocument7 pagesAnalysis of A Failed Pipe Elbow in Geothermal Production Facility PDFAz ArNo ratings yet

- CFD NotesDocument155 pagesCFD NotesAjit ChandranNo ratings yet

- 05-PT11-Cascade Aerodynamics (Compatibility Mode)Document45 pages05-PT11-Cascade Aerodynamics (Compatibility Mode)Venkat Pavan100% (1)

- CFD Numerical 2007 IntermediateDocument40 pagesCFD Numerical 2007 Intermediatehlkatk100% (1)

- Modeling and FE Analysis OverallDocument54 pagesModeling and FE Analysis OverallBunny Goud PerumandlaNo ratings yet

- 13 - Chapter 5 CFD Modeling and Simulation - 2Document28 pages13 - Chapter 5 CFD Modeling and Simulation - 2Zahid MaqboolNo ratings yet

- I. Principles of Wind EnergyDocument3 pagesI. Principles of Wind EnergyJohn TauloNo ratings yet

- Conical Solar StillDocument27 pagesConical Solar StillAbhijeet EkhandeNo ratings yet

- Protecting Environment Through EngineeringDocument19 pagesProtecting Environment Through EngineeringAce HombrebuenoNo ratings yet

- Ehlen Fluent DeutschlandDocument43 pagesEhlen Fluent DeutschlandAhmed AhmedovNo ratings yet

- SPE 89334 Analysis of The Effects of Major Drilling Parameters On Cuttings Transport Efficiency For High-Angle Wells in Coiled Tubing Drilling OperationsDocument8 pagesSPE 89334 Analysis of The Effects of Major Drilling Parameters On Cuttings Transport Efficiency For High-Angle Wells in Coiled Tubing Drilling OperationsmsmsoftNo ratings yet

- Coupled Scheme CFDDocument3 pagesCoupled Scheme CFDJorge Cruz CidNo ratings yet

- Differential Transformation Method for Mechanical Engineering ProblemsFrom EverandDifferential Transformation Method for Mechanical Engineering ProblemsNo ratings yet

- A Three-Dimensional Simulation of Mine Ventilation Using Computational Fluid DynamicsDocument3 pagesA Three-Dimensional Simulation of Mine Ventilation Using Computational Fluid DynamicsTariq FerozeNo ratings yet

- Heat Transfer Coefficient PDFDocument57 pagesHeat Transfer Coefficient PDFAnmol Preet SinghNo ratings yet

- 10-1108 Eum0000000004086Document17 pages10-1108 Eum0000000004086Yasser AlrifaiNo ratings yet

- A Project Report On Turbulent FlowsDocument14 pagesA Project Report On Turbulent FlowsNishant KumarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 ConvectionDocument123 pagesChapter 3 ConvectionPHƯƠNG ĐẶNG YẾNNo ratings yet

- 3-D Numerical simulation of swirling flow and convective heat transferDocument24 pages3-D Numerical simulation of swirling flow and convective heat transferVenkat Rajesh AnapuNo ratings yet

- CFD FinalDocument17 pagesCFD FinalSameer NasirNo ratings yet

- Quasi-Two-Dimensional MHD Duct Flow Around A 180-Degree Sharp Bend in A Strong Magnetic FieldDocument4 pagesQuasi-Two-Dimensional MHD Duct Flow Around A 180-Degree Sharp Bend in A Strong Magnetic Fieldkoushikthephoenix1No ratings yet

- Computational Wind Engineering 1: Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium on Computational Wind Engineering (CWE 92) Tokyo, Japan, August 21-23, 1992From EverandComputational Wind Engineering 1: Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium on Computational Wind Engineering (CWE 92) Tokyo, Japan, August 21-23, 1992S. MurakamiNo ratings yet

- Topology Optimization of A Wing Box RibDocument131 pagesTopology Optimization of A Wing Box Ribdjtj89100% (1)

- ME3601 Prof Eng PracticeDocument3 pagesME3601 Prof Eng Practicedjtj89No ratings yet

- Stress Concentration PDFDocument8 pagesStress Concentration PDFkanak kalitaNo ratings yet

- Statistics SummaryDocument9 pagesStatistics Summarydjtj89No ratings yet

- Contents Aircraft Landing GearDocument1 pageContents Aircraft Landing Geardjtj89No ratings yet

- Term 1Document2 pagesTerm 1djtj89No ratings yet

- Critical ReviewDocument1 pageCritical Reviewdjtj89No ratings yet

- Aircraft Design AnalysisDocument9 pagesAircraft Design Analysisdjtj89100% (1)

- CFD Simulation IntroductionDocument30 pagesCFD Simulation Introductiondjtj89No ratings yet

- NACA 23014 (Mod) - 416Document406 pagesNACA 23014 (Mod) - 416djtj89No ratings yet

- UAV Drone ComparisonDocument14 pagesUAV Drone Comparisondjtj89No ratings yet

- Environmental Law Final-2013Document71 pagesEnvironmental Law Final-2013djtj89No ratings yet

- Airfoil Geometry DataDocument26 pagesAirfoil Geometry Datadjtj89No ratings yet

- Topology Optimization of Aircraft Wing Box RibsDocument3 pagesTopology Optimization of Aircraft Wing Box Ribsdjtj89No ratings yet

- Excel To CATIADocument6 pagesExcel To CATIAdjtj89No ratings yet

- Siemens NX - GuidanceDocument8 pagesSiemens NX - Guidancedjtj89100% (1)

- Agusta WestlandDocument7 pagesAgusta Westlanddjtj89No ratings yet

- ME3608 Aeroelasticity #1Document31 pagesME3608 Aeroelasticity #1djtj89No ratings yet

- Thermofluids ME2301Document1 pageThermofluids ME2301djtj89No ratings yet

- Literature Review PlanDocument1 pageLiterature Review Plandjtj89No ratings yet

- A History of Canadian Naval Aviation 1918-1963Document169 pagesA History of Canadian Naval Aviation 1918-1963djtj89100% (3)

- Sections and Threads PDFDocument1 pageSections and Threads PDFdjtj89No ratings yet

- Environmental Law Final-2013Document71 pagesEnvironmental Law Final-2013djtj89No ratings yet

- Seminar19 PDFDocument4 pagesSeminar19 PDFdjtj89No ratings yet

- ME3602 - ME3692 FEA Assignment 2013 - 2014: K A P KDocument3 pagesME3602 - ME3692 FEA Assignment 2013 - 2014: K A P Kdjtj89No ratings yet

- ME3608 Aeroelasticity #1Document31 pagesME3608 Aeroelasticity #1djtj89No ratings yet

- Tut - Basic RefrigerationDocument3 pagesTut - Basic Refrigerationdjtj89No ratings yet

- Technical Drawing Intro PDFDocument1 pageTechnical Drawing Intro PDFdjtj89No ratings yet

- TOOLKIT For MPDS-August12 PDFDocument13 pagesTOOLKIT For MPDS-August12 PDFdjtj89No ratings yet

- Naming TutorialDocument32 pagesNaming TutorialLÂM VŨ THÙYNo ratings yet

- BEHAVIOR OF STRUCTURES UNDER BLAST LOADINGDocument32 pagesBEHAVIOR OF STRUCTURES UNDER BLAST LOADINGramyashri inalaNo ratings yet

- Zeu 1223 Proficiency English 2 Topic: Greenhouse EffectDocument22 pagesZeu 1223 Proficiency English 2 Topic: Greenhouse EffectJuni CellaNo ratings yet

- BL ExoticaDocument91 pagesBL ExoticaFREDDYMENANo ratings yet

- In Vitro Evaluation of Glimepiride Solid Dispersions for Dissolution Rate EnhancementDocument12 pagesIn Vitro Evaluation of Glimepiride Solid Dispersions for Dissolution Rate Enhancementmanvitha varmaNo ratings yet

- Reduction of Phenylalanine To AmphetamineDocument2 pagesReduction of Phenylalanine To AmphetamineFlorian FischerNo ratings yet

- Astm D512 - 12 - Cloruros en AguaDocument9 pagesAstm D512 - 12 - Cloruros en AguaEliasNo ratings yet

- Chemical Bath Deposition: Mark - Deguire@case - EduDocument21 pagesChemical Bath Deposition: Mark - Deguire@case - EduH Cuarto PeñaNo ratings yet

- Proposal FormatDocument21 pagesProposal Formatግሩም ግብርከNo ratings yet

- catalogue-BW SeriesDocument2 pagescatalogue-BW SeriessugiantoNo ratings yet

- Thermochemistry: Nature of EnergyDocument5 pagesThermochemistry: Nature of EnergyChristina RañaNo ratings yet

- Cems A 9Document20 pagesCems A 9Engenharia APedroNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Introduction To Management Accounting 15th Edition Horngren Solutions Manual PDFDocument36 pagesDwnload Full Introduction To Management Accounting 15th Edition Horngren Solutions Manual PDFcalymene.perdurel7my100% (11)

- The Pure Substance:: A Pure Substance Is One That Has A Homogeneous and Invariable Chemical CompositionDocument113 pagesThe Pure Substance:: A Pure Substance Is One That Has A Homogeneous and Invariable Chemical CompositionHrishikesh ReddyNo ratings yet

- Graham Cracker ExperimentDocument12 pagesGraham Cracker Experimentapi-2961255610% (1)

- IRRIGATION SYSTEMS DESIGN NOTES - MR Mpala LSUDocument163 pagesIRRIGATION SYSTEMS DESIGN NOTES - MR Mpala LSUPanashe GoraNo ratings yet

- Jantzen Brix P. Caliwliw ME-1 A42 Chapter 2: Atoms, Molecules, and IonsDocument2 pagesJantzen Brix P. Caliwliw ME-1 A42 Chapter 2: Atoms, Molecules, and IonsJantzenCaliwliwNo ratings yet

- Determination of The Diffraction Intensity at Slit and Double Slit SystemsDocument5 pagesDetermination of The Diffraction Intensity at Slit and Double Slit SystemsJose Galvan100% (1)

- 1.5 LipidsDocument19 pages1.5 Lipidsasifh76543No ratings yet

- Fundamentals of ChemistryDocument385 pagesFundamentals of Chemistryalexmulengamusonda214No ratings yet

- Testing and inspection of weld joints guideDocument64 pagesTesting and inspection of weld joints guideyashNo ratings yet

- Bruker 820 Ms Brochure CompressedDocument10 pagesBruker 820 Ms Brochure Compresseddayse marquesNo ratings yet

- Concrete ADM STD Specifications For K-140 SRC & K-250 SRC ROAD WorksDocument22 pagesConcrete ADM STD Specifications For K-140 SRC & K-250 SRC ROAD WorksMubashar Islam JadoonNo ratings yet

- Coal - Cargoes - IMSBC Code PDFDocument7 pagesCoal - Cargoes - IMSBC Code PDFRadhakrishnan DNo ratings yet

- MODULE 3 - Earth Sci: Earth Science Grade Level/Section: Subject TeacherDocument5 pagesMODULE 3 - Earth Sci: Earth Science Grade Level/Section: Subject Teacheryhajj jamesNo ratings yet

- Asignment - Chapter 1 PDFDocument3 pagesAsignment - Chapter 1 PDFDo Cong Minh100% (1)

- LG SW 440 GRDocument1 pageLG SW 440 GRkylealamangoNo ratings yet

- Earth Science ActivitiesDocument10 pagesEarth Science ActivitiescykenNo ratings yet

- Electrochemistry Past Papers 2022-14Document4 pagesElectrochemistry Past Papers 2022-1410 A Pratyush Dubey0% (1)