Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Two Truths

Uploaded by

Ericson ChewCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Two Truths

Uploaded by

Ericson ChewCopyright:

Available Formats

The Two Truths

Please prepare this session by generating a mind of enlightenment, bodhicitta, to benefit the limitless number of sentient beings. I rejoice to have the opportunity to come here and teach the holy teaching of the Lord Buddha. Most of the participants in this audience now me, and this gives me an especially good feeling. !n important term in Tibetan Buddhism is nang, which means "inner# or "interior.# $appiness and misery shall not be understood with regard to e%ternal objects, and to attain ultimate and unchanging happiness, one needs to reali&e one's innermost being. (ne must strive to study the wor ings of the mind. )hen we reali&e our innermost being, we will reali&e the meaning of life and the meaning of the happiness that we e%perience in our life. In Buddhist teachings, the term "happiness# refers to authentic happiness. In the beginning is it important to study the teachings of the Buddha. The ancient Indian master, called *igniga, said, "Initially one should e%ert oneself in studying, followed by a phase of reflection, which should be followed a phase of meditation practice.# By engaging oneself in the study of the Buddha's teachings, one will achieve peace of mind. By gleaning wisdom from listening and studying, one can cut through the doubt and hesitation with regard to the ultimate truth and ac+uire a very determined mind. )hen one has gained certainty of the ultimate truth through listening and studying, as well as reflection and contemplation, one needs to implement this certainty by uniting it with the phase of meditation. By relying on the wisdom that comes from meditation, one will be able to uproot the disturbing emotions. The ,yingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism places a great deal of emphasis on analytical contemplation, which is the initial process of listening and studying. If one initially does not ac+uire the wisdom that comes from profound analysis, it is impossible to ac+uire wisdom from meditation. If concentrative meditation is not united with the analytical contemplation, by for e%ample only favoring analytical meditation, the Tibetan e%pression "idiot meditator# may be applicable. ,o benefit will come from such meditation. -o, one should unite analytical contemplation with concentrative meditation. Then, one should only do

concentrative meditation. I brought up this in order to underline the importance of the processes of listening, contemplating and meditating. I studied the teaching of the Buddha for ten years, and then meditation came +uite easily. !s sentient beings, we are e%troverted. )e tend to perceive e%ternal objective phenomena through our senses. Therefore, we are not able to turn our mind inwards and loo at ourselves. It is easy for you to see the stain on somebody else's face, but it ta es effort to see the stain on one's own. The same goes for the sense of hearing. (ur bodies ma e numerous sounds that we seldom hear, although we easily hear sounds from outside. Because of the function of the five senses of sentient beings, we are capable of developing a lot of discursive thoughts. The mind that is occupied with discursive thoughts is a deluded mind that tries to establish what is pure and what is impure, what is right and what is wrong, what is deluded and what is not deluded, what is true and what is untrue. The deluded mind tries to decide what we see and hear by using our senses. But the mind of the Buddha perceives e%ternal phenomena in a completely different way. as lac ing true e%istence and characteristics. Phenomena that have no characteristics do not e%ist. To +uote the heart sutra. "The 'I' does not have any true characteristics/ the ear does not have any true characteristics/ the tongue does have any true characteristics.# This can be applied to all sensory organs, to the sensory consciousnesses, and to the mind 0 they all lac true e%istence. If all these things lac true e%istence, then what is the truth1 !ccording to the teaching of the Buddha, there are two levels of truth. The first truth is relative truth/ the second truth is absolute truth. The Tibetan word for relative truth implies "all# and "without essence.# !ll samsaric phenomena are impermanent. -uch phenomena can be very deceptive. It is easy to observe that all phenomena are impermanent/ one can see an infant born and gradually grow into a toddler, adolescent, and adult. !lso, our e feelings change. -ometimes we e%perience joy/ sometimes misery. Impermanence applies e+ually to the e%ternal element of nature. It is difficult to find ultimate fulfillment. (ne can aspire to become wealthy, and thin that one will be happy by the time one has a certain amount of money in the ban . $owever, as soon as this happens, one wants to have even more. It is

therefore difficult for a samsaric being to attain ultimate fulfillment. The Buddha said that lac ing something is an illusion, and so is not lac ing something. )hen we lac something that we want we are miserable. This situation changes when we obtain something that we want, but cannot guarantee our happiness because new miseries will accompany the possession of new things. !ll discursive thoughts can be traced to the three disturbing emotions. attachment, anger and ignorance. The presence of discursive thoughts in a mind that is filled with these emotions ma es it very difficult for us to attain the omniscient state of the Buddha. To reali&e relative truth, one must understand impermanence. Impermanence should be understood in terms of birth. Birth is followed by destruction. If you, as a meditator, reali&e the meaning of the relative truth in this way, you will receive immense benefit even if you lac the reali&ation of the ultimate truth. $owever, if you believe in the permanence of the relative truth with regard to your beloved, with regard to your spouse, with regard to your friends and family, or material objects, you will suffer. But again, if you reali&e the impermanence of relative truth with regards to all those things, you will be at peace. If one observes the physical e%istence of Buddha -ha yamuni, one would see the nature of impermanence affecting his body, but the mind of Buddha -ha yamuni, is enlightened and don't now the miseries of birth, old age, sic ness and death. The view that holds onto the permanence, the true e%istence, and the singularity of the e%ternal phenomena, is a perverted view. In contrast, if you reali&e the impermanent, selfless, empty, and suffering nature of the e%ternal phenomena, particularly with regard to your physical e%istence, your mind will not be perverted. To understand the meaning of relative truth, it is essential to reali&e the meaning of impermanence. Instead of trusting the objective phenomena, one should reali&e that the e%ternal phenomena do not hold absolute happiness. They are tainted by misery and suffering. If we reali&e the impermanent nature of the objective reality of the objective phenomena, such a reali&ation corresponds to the universal truth. If this understanding develops into the reali&ation of the

emptiness of the true e%istence of objective phenomena, this is the reali&ation of emptiness, the absolute truth. The ultimate truth lies beyond the domain of e%pression and description. !bsolute truth cannot be e%pressed because our mind is powerless to do so. (ur mind nows only two things. the e%treme of e%istence and the e%treme of non2 e%istence. (ur mind cannot go beyond these two e%tremes. 3or e%ample, if you cannot see something, you will not believe that it e%ists. The same applies to our sense organs. 3or e%ample, the ear is rather small, with a small hole, and there is an infinite number of sounds that we cannot hear. )e believe the sounds we can hear, we do not believe the sounds we cannot hear. The same applies to the nose, tongue, and the s in/ their capacity to discern is very wea . Because of this, we are not able to understand all phenomena. 4arlier I said that the sense organs lac characteristics. Because of this, our sense organs are incapable of perceiving the whole spectrum of reality. This is why the Buddha said that the sense organs lac characteristics, or true e%istence. (ne of the Tibetan scholars said that if our eyes were placed in a different position, for e%ample vertical, then our reality would be completely changed. )hen the Buddha said that the three realms are only in the mind, it means that the actual determining factor is one's own mind. The phenomena are not determined by the objective reality. They are determined by how our minds perceive them. If we close our eyes and prevent our sense organs from being distracted, this is a ind of meditation. In the sutra the Buddha tal s about the threefold meditation or samadhi meditation 5-ans rit. to ma e firm, one2pointed concentration6. The Buddha tal s about the samadhi that is associated with the three gates of the body, speech and mind. 3or e%ample, if you open the gates of your mind or sense organs, then many discursive thoughts will come through. But if you shut the gates, then the discursive thought will be bloc ed from your mind. The Buddha gave instruction on how to practice closing the gates of one's body, speech and mind. $e said that one should sit still, remain silent, and concentrate. If you could practice this simple meditation techni+ue of in a +uiet place for seven days, then you will certainly be able to suppress your conflicting emotions, at least while you are meditating. If you cannot do this for one wee , then you probably will not be able to gain control over your disturbing emotions.

(ur many past lives have made us very familiar with our disturbing emotions. Therefore, it is crucial for the meditator to use mindfulness to loo within his or her mind. This is meditation. In this way, one can practice meditation in formal sessions and implement whatever meditative e%perience one has gained in the informal period, into one's daily life. )hen the formal meditation session is supplemented with post meditation practice, then one is not only able to suppress and gain control over one's disturbing emotions, but one will be capable of eradicating the root of the disturbing thoughts and emotions. It is therefore important to combine the actual meditation session with the post meditation session. This has been a very brief presentation of the relative truth and the ultimate truth. *o you have +uestions1 7uestion. Is analytical meditation an absolute necessity for a real meditation e%perience1 The Buddha teaches about the emptiness of self. (ne should not accept the teaching of the Buddha at face value/ one should thoroughly analy&e the teachings. There is a reason the Buddha gave the teaching on emptiness of the self, and one needs to reali&e the validity of this reason. To do this one must analy&e and use one's investigative powers. 3or e%ample, in the practice of being mindful of one's body, one should observe one's body and try to determine whether there e%ists a self within the body or not. The Indian Buddhist master 8handra irti laid out the seven2fold reasoning of no2self of the chariot. If you meditate upon this seven2fold reasoning, then you are doing analytical meditation. -ince infinite time we have accustomed to thin ing that an ego e%ists. )hatever we do is based on the true e%istence of self. )e put a tremendous amount of trust into the notion. )e trust what "I# thin is true, what "I# state is true. )hatever the self does, we thin is absolutely right. If we build the ego in this manner, then this self will become so huge that it ma es it difficult for us to see others. Because of the law of interdependence, it is impossible to e%perience happiness for oneself without e%periencing happiness for other sentient beings. This implies

that our e%perience is intimately connected with that of our fellow beings. Therefore, the Buddha claims that the e%istence of the self is responsible for suffering. The Buddha has also said that the altruistic mind brings about benefit for all living beings. In order to trust the teachings of the Buddha, one needs to study, listen, reflect and meditate. Then one can become convinced of the validity of these teachings. This is the foundation of the teaching of the Buddha. 4verybody nows this, but it bears repeating. I believe that many of you are +uite nowledgeable on this topic, and that many of you have been practicing for many years. 9ou are therefore a most receptive audience. It is crucial for a teacher to share his personal understanding with such an audience. 7uestion. But you can study for a lifetime without being finished. )hen does one now that one should stop studying and go into retreat instead1 )hen you gain a profound certainty with regard to the emptiness of self, you can drop your studies and apply this understanding to your meditation practice. But until you develop this profound certainty, you should continue your study. But if you still pursue your academic study through listening and reading after you have reali&ed the meaning of the view, this is no point, because you have found your lost elephant. *uring the time of the Buddha, the elephant was a very special and beloved animal. That is why the elephant is used as a symbol in the Buddhist te%ts. 7uestion. I am a bit confused about the term "study# in this conte%t, because the way it is being presented it seems to imply more than an intellectual understanding 0 that there is an insight as well that must be gained by meditation. 8an you e%plain a little bit more about the meaning of study in this conte%t1 If you are capable of digesting the teaching, when you hear instructions from a meditation master, this teaching will actually create peace in your mind, and this peace will permeate your body and your speech. Therefore the sign of having studied and heard teachings is the e%perience of peace. !nd the sign of whether you have meditated is the absence of discursive thoughts. By relying on the phase of study and listening you are li ely to generate the

meditative e%perience of shamatha. But such a process alone will not guarantee the reali&ation of the vipashyana, or insight meditation. :iving rise to the e%perience of shamatha meditation will bring your closer to the successive meditation e%periences that will lead you to the e%perience of the vipashyana meditation. 3or e%ample, while you are studying and listening, instead of letting your mind become distracted, focus on what you are studying and hearing/ this constitutes the practice of one2 pointed concentration. !lso, because the objective focus of your meditation is a virtuous object, because you are studying dharma, your mind will be protected from non virtuous objects, at least while you are studying. This type of practice will constitute the practice of both the *harma and meditation. Buddhist practice should not be understood only in terms of escaping to an isolated retreat and staying within a small cell. !ny practice that will lessen one's discursive thoughts or conflicting emotions constitutes Buddhist meditation practice. If the phase of study and listening allows you to e%clude discursive thoughts, then this also constitutes a practice. To use an e%ample, compounds that cure an illness are called "medicine.# But if these compounds cannot eliminate illness, you cannot call it "medicine.# If you are able to lessen or prevent your discursive thoughts from occurring, whether from listening or contemplation or meditation, then this is the practice of meditation. Before we enter into the gates of *harma, our minds entertain many polarities and e%tremes such as e%istence, non2e%istence, good and bad, and so on ad infinitum. )hen we enter the *harma, the creation of polarities stops, and one will not loo upon study and listening as not being meditation. )e often thin that one particular aspect of *harma is not meditation, whereas another is genuinely lin ed with meditation practice. This habit of creating polarities within the *harma will interfere with the practice, but if you understand the meaning of *harma though the process of study and listening, it is possible to unite all the trivial acts that one performs in one's daily life 0 such as wa ing up, wal ing around, sitting or sleeping 0 within the practice of *harma. 4veryday actions can be transformed into virtuous actions. This transformation can happen because we now how to do so. -ometimes we thin that we can only meditate by separating ourselves from

society, but it is possible to meditate within a society. (ne does not need to distance oneself from regular life. 3or e%ample, eating is an ordinary activity. The act of eating can be united with meditation, and if you are eating with your totality, with your whole being, then the act becomes whole and total. Then you now the meditative art of eating. By eating in this way, the food becomes tastier and more nutritious. 3or e%ample, if the Buddha were to eat bad food, even grass eaten by horses, he would be able to e%tract nutrition from that food as if he were eating very wholesome food. That is because his body, speech and mind are ta ing part in the process of eating. !lso, if we implement our meditation practice with wal ing, eating, sitting and so on, then our mind will calm down. 7uestion. -ometimes I feel vipashyana is li e going through lists, li e the seven fold reasoning of emptiness. In a way it becomes so familiar that the vitality is lost. The process seems to become mechanical and boring. $ow should I avoid that1 To avoid e%periencing boredom one needs to alternate analytical meditation with concentrative meditation. Most of the people of Tibet spend their lives high up in the mountains. They are eager to see these big cities, and one day maybe they find themselves in such a city, but after having been there they want to go bac to the pure mountains. It is similar to this. (ne goes in circles/ this is samsara. )hen we develop a sense of weariness with regard to the discursive mind, our mind will not be so interested in producing thoughts. Therefore, a certain amount of weariness is desirable. $owever, the conceptual mind does possess certain +ualities, and therefore one should not condemn it. The conceptual mind allows us to ma e the journey from the discursive mind to the non2discursive mind. In this way the discursive mind forms a ground. !lso, we should not condemn individuals who are entertaining discursive thoughts by thin ing that "I have fewer discursive thoughts than that person.# 8hinese Buddhists, especially mon s and nuns living in monasteries, are strictly vegetarian. )hen you meet such practitioners, some will brag about their vegetarianism and loo down upon those who are not vegetarians. If one's vegetarianism gives rise to such arrogant thoughts, then this practice has not done much good, apart for not eating flesh. These vegetarians should develop compassion towards the non2vegetarians, because of their craving for meat.

In the same way, the practice of humility with regard to all sentient beings is crucial. If I, as a Buddhist, have a philosophy that is profounder then that of others, or that my religion is more genuine than others, this will increase ego and arrogance, which will lead to the condemnation of others. If this is the case, then my engagement in Buddhist practice does not serve any real purpose. !s we practice, gradually a shift ta es place in our mind so that we are capable of generating a sense of love and compassion even towards our enemy. This shift occurs because of a transformation of attitude. !ctually, even if we thin we have has an enemy, in reality the e%ternal enemy is neither our friend nor our enemy. The actual nature of the so called enemy eludes both friend and enemy. If you study the *harma through listening and hearing, reflection and meditation, and ac+uire the corresponding wisdom, this wisdom will have the power to change your mind to perceive the reality, as it is, not in limited way. !lso, in a real sense medicine is not medicine, nor is it poison. It depends on the one ta ing the medicine. )hether you perceive the phenomenal world as pure or impure depends solely on your perceiving mind. )e cannot describe the e%ternal world as pure or impure. The e%ternal world escapes both purity and impurity, because in the final analysis the perceiving mind decides whether it is pure or impure. This world can be a paradise or a hell. !s the Buddha said, "I have showed you the path to liberation. ,ow, whether you gain the enlightenment of liberation or not is your responsibility.# This means that your attitude and perspective are the most crucial elements. !s we said earlier, the phenomenal world of the three realms is nothing more than a creation of one's mind. If one understands these teachings, then this place can be paradise wherever one actually is. If one does not reali&e this, one will go through hell on earth. If one lac s this understanding, then even if one were to meet !mitabha, the Buddha of boundless light, one will not be able to recogni&e him. But if one reali&es this meaning, then the ne%t person transfigures into the Buddha of boundless light. In the sutras, the Buddha says that the nature of all living being is sugatagarbha, Buddha2nature. In the tantric teaching, the Buddha says that all phenomenal e%perience and appearance in reality is infinite purity.

(slo, ;une <==> Translated by Lama 8hangchub at ?arma Tashi Ling Buddhist 8entre, ,orway

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Noble Wisdom of The Time of Death Sūtra and Commentaries PDFDocument98 pagesThe Noble Wisdom of The Time of Death Sūtra and Commentaries PDFRaphael Krantz100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Benefits of The Vajra Guru MantraDocument6 pagesThe Benefits of The Vajra Guru MantraDirk JohnsonNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- FourEmpowermentsChartDocument2 pagesFourEmpowermentsChartEricson ChewNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Wish Fulfilling Wheel Cherizig SadhanaDocument28 pagesWish Fulfilling Wheel Cherizig SadhanaEricson ChewNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- A Commentary On The Concise Daily Practice of PadmasambhavaDocument6 pagesA Commentary On The Concise Daily Practice of PadmasambhavaEricson Chew100% (2)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Homage and Offerings To The Sixteen Elders Lecture 1 1110Document47 pagesHomage and Offerings To The Sixteen Elders Lecture 1 1110Ericson ChewNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Chenrezig Arya Avalokiteshvara Singhanada Exalted Lions Roar c5Document12 pagesChenrezig Arya Avalokiteshvara Singhanada Exalted Lions Roar c5Ericson Chew100% (3)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Benefits of CircumambulationsDocument2 pagesThe Benefits of CircumambulationsEricson ChewNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Ganapati's Exalted Heart-DharaniDocument2 pagesGanapati's Exalted Heart-DharaniEricson Chew100% (1)

- LogyonmaDocument1 pageLogyonmaPohSiangNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Merits of Turning The Prayer WheelDocument9 pagesThe Merits of Turning The Prayer WheelShenphen OzerNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Wheel of Great Compassion WisdomDocument170 pagesThe Wheel of Great Compassion WisdomLiu Fengshui100% (2)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Melody 17 PDFDocument84 pagesMelody 17 PDFEricson ChewNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Life and Spirituality EnglishDocument438 pagesLife and Spirituality EnglishEricson ChewNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- MindfulnessDocument3 pagesMindfulnessEricson ChewNo ratings yet

- Practices To Do For SuccessDocument15 pagesPractices To Do For SuccessEricson ChewNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Lama Norlha TeachingDocument8 pagesLama Norlha TeachingEricson Chew100% (1)

- King of Samadhi SutraDocument19 pagesKing of Samadhi SutraEricson Chew100% (2)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Buddha Dhamma C AkraDocument76 pagesBuddha Dhamma C AkraEricson ChewNo ratings yet

- Karundavyuha Gunakarandavyuha SutraDocument51 pagesKarundavyuha Gunakarandavyuha Sutrataran1080No ratings yet

- Katha Bucha Nang GwakDocument1 pageKatha Bucha Nang GwakEricson ChewNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Tree of EnlightenmentDocument402 pagesThe Tree of EnlightenmentJaime GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Karundavyuha Gunakarandavyuha SutraDocument51 pagesKarundavyuha Gunakarandavyuha Sutrataran1080No ratings yet

- Buddha Pronounces The Sūtra of Neither Increase Nor DecreaseDocument6 pagesBuddha Pronounces The Sūtra of Neither Increase Nor DecreaseEricson ChewNo ratings yet

- A Heart Released Ahjaan MunDocument25 pagesA Heart Released Ahjaan MunEricson ChewNo ratings yet

- Khenpo Kunpal Bodhicaryavatara CH 1Document587 pagesKhenpo Kunpal Bodhicaryavatara CH 1shresthachamil100% (1)

- Esposito Zogchen in ChinaDocument87 pagesEsposito Zogchen in Chinapemagesar100% (1)

- The Dharani For The Fulfillment of Aspiration Prayers - 53-EnDocument3 pagesThe Dharani For The Fulfillment of Aspiration Prayers - 53-EnFairy LandNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Short Method For Reciting Samantabadra PrayerDocument1 pageA Short Method For Reciting Samantabadra PrayerEricson ChewNo ratings yet

- Bedwetting TCMDocument5 pagesBedwetting TCMRichonyouNo ratings yet

- Principles of Health Management: Mokhlis Al Adham Pharmacist, MPHDocument26 pagesPrinciples of Health Management: Mokhlis Al Adham Pharmacist, MPHYantoNo ratings yet

- Fill The Gaps With The Correct WordsDocument2 pagesFill The Gaps With The Correct WordsAlayza ChangNo ratings yet

- Finite Element Analysis Project ReportDocument22 pagesFinite Element Analysis Project ReportsaurabhNo ratings yet

- 1A Wound Care AdviceDocument2 pages1A Wound Care AdviceGrace ValenciaNo ratings yet

- How To Import Medical Devices Into The USDocument16 pagesHow To Import Medical Devices Into The USliviustitusNo ratings yet

- Neuro M Summary NotesDocument4 pagesNeuro M Summary NotesNishikaNo ratings yet

- DEIR Appendix LDocument224 pagesDEIR Appendix LL. A. PatersonNo ratings yet

- Ec Declaration of Conformity: W1/35 KEV KIRK - Protective Gloves - Cathegory IIDocument3 pagesEc Declaration of Conformity: W1/35 KEV KIRK - Protective Gloves - Cathegory IICrystal HooverNo ratings yet

- Method Statement (RC Slab)Document3 pagesMethod Statement (RC Slab)group2sd131486% (7)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- NRF Nano EthicsDocument18 pagesNRF Nano Ethicsfelipe de jesus juarez torresNo ratings yet

- CONTROLTUB - Controle de Juntas - New-Flare-Piping-Joints-ControlDocument109 pagesCONTROLTUB - Controle de Juntas - New-Flare-Piping-Joints-ControlVss SantosNo ratings yet

- METHOD STATEMENT FOR INSTALLATION OF Light FixturesDocument5 pagesMETHOD STATEMENT FOR INSTALLATION OF Light FixturesNaveenNo ratings yet

- READING 4 UNIT 8 Crime-Nurse Jorge MonarDocument3 pagesREADING 4 UNIT 8 Crime-Nurse Jorge MonarJORGE ALEXANDER MONAR BARRAGANNo ratings yet

- User ManualDocument21 pagesUser ManualKali PrasadNo ratings yet

- Goals in LifeDocument4 pagesGoals in LifeNessa Layos MorilloNo ratings yet

- Big 9 Master SoalDocument6 pagesBig 9 Master Soallilik masrukhahNo ratings yet

- Pip-Elsmt01 P66 Midstream Projects 0 1/02/18: Document Number S & B Job Number Rev Date SheetDocument11 pagesPip-Elsmt01 P66 Midstream Projects 0 1/02/18: Document Number S & B Job Number Rev Date SheetAjay BaggaNo ratings yet

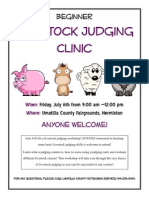

- Jun Judging ClinicDocument1 pageJun Judging Cliniccsponseller27No ratings yet

- High Speed DoorsDocument64 pagesHigh Speed DoorsVadimMedooffNo ratings yet

- ASOTDocument4 pagesASOTemperors_nestNo ratings yet

- Tamilnadu Shop and Establishment ActDocument6 pagesTamilnadu Shop and Establishment ActShiny VargheesNo ratings yet

- How McDonald'sDocument2 pagesHow McDonald'spratik khandualNo ratings yet

- Heteropolyacids FurfuralacetoneDocument12 pagesHeteropolyacids FurfuralacetonecligcodiNo ratings yet

- Heart Sounds: Presented by Group 2A & 3ADocument13 pagesHeart Sounds: Presented by Group 2A & 3AMeow Catto100% (1)

- Assignment - Lab Accidents and PrecautionsDocument6 pagesAssignment - Lab Accidents and PrecautionsAnchu AvinashNo ratings yet

- Dungeon World ConversionDocument5 pagesDungeon World ConversionJosephLouisNadeauNo ratings yet

- Task 5 Banksia-SD-SE-T1-Hazard-Report-Form-Template-V1.0-ID-200278Document5 pagesTask 5 Banksia-SD-SE-T1-Hazard-Report-Form-Template-V1.0-ID-200278Samir Mosquera-PalominoNo ratings yet

- QA-QC TPL of Ecube LabDocument1 pageQA-QC TPL of Ecube LabManash Protim GogoiNo ratings yet

- University of Puerto Rico at PonceDocument16 pagesUniversity of Puerto Rico at Ponceapi-583167359No ratings yet

- The Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthFrom EverandThe Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (179)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismFrom EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- Stoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionFrom EverandStoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (51)

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- A Short History of Modern Philosophy: From Descartes to WittgensteinFrom EverandA Short History of Modern Philosophy: From Descartes to WittgensteinRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- You Are Not Special: And Other EncouragementsFrom EverandYou Are Not Special: And Other EncouragementsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)