Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pakisatn Beyond Crsis

Uploaded by

Canna IqbalOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pakisatn Beyond Crsis

Uploaded by

Canna IqbalCopyright:

Available Formats

Pakistaniaat : A Journal of Pakistan Studies Vol. 3, No.

3 (2011)

Pakistan: Beyond the Crisis State Reviewed by David Waterman

Pakistan: Beyond the Crisis State. Maleeha Lodhi, ed. London: Hurst and Company, 2011. 391 pages. ISBN-13: 978-1-84904-135-5. Maleeha Lodhi, as the editor of Pakistan: Beyond the Crisis State, has managed to assemble some of Pakistans most influential academics, writers, economists and policymakers in one volume, designed to give an insiders perspective on Pakistans crisis from diverse angles, and more importantly, to suggest solutions regarding Pakistans obvious potential for a better future. The book is not a collection of conference proceedings, but rather the product of a virtual conference in cyberspace, discussing themes of governance, security, economic and human development and foreign policy [] what binds all the distinguished contributors is their belief that Pakistans challenges are surmountable and the impetus for change and renewal can only come from within, through bold reforms that are identified in the chapters that follow (3). The first few chapters concentrate on Pakistans history and the sense of a Pakistani identity, now that the country has existed in very concrete terms for sixty-five years or so. Ayesha Jalal suggests that Pakistans path toward a national identity for its heterogeneous people has been interrupted, as its history has been co-opted for political and ideological reasons (11). Pakistans position vis--vis India, militant Islam and 9/11 are all important factors in the equation as well. Akbar Ahmed recalls Jinnahs role not only in the founding of the nation, but his continuing legacy in terms of an equilibrium between Islam and the State; Jinnahs thoughts are in large part gleaned from his speeches and letters, as he left no monograph before his death (23). Mohsin Hamid, author of Moth Smoke and The Reluctant Fundamentalist (filming for the movie has apparently begun), assumes his mantle of engaged journalist in an essay entitled Why Pakistan will Survive. His argument is best summed up as follows: we are not as poor as we like to think (41), highlighting Pakistans strength in diversity, and in economic terms, Hamid suggests that something as simple as a coherent, fair tax code could allow the nation to concentrate on schools and healthcare, while cutting the strings of American aid and its corresponding intervention in Pakistans affairs. Maleeha Lodhis own chapter is a detailed overview of contemporary history, calling attention to political asymmetry, clientelist politics and borrowed growth

David Waterman as well as security concerns and regional pressures on national unity; ultimately she calls for a new politics that connects governance to public purpose (78). The essays then move into more political themes, and the first among them discusses the army as a central element of Pakistani political, and indeed corporate, life. Shuja Nawaz argues that while the army has historically been a significant power broker, the generation of commanders from the Zia and Musharraf eras is about to retire, thus promising the possibility of change, including the realization that counterinsurgency operations are 90 per cent political and economic and only 10 per cent military (93). Saeed Shafqat also discusses the political role of the military, saying that while elections are of course essential to democracy, more attention needs to be paid to the rule of law and the incorporation of cultural pluralism (95), never forgetting the role of various elites within the process; he suggests that the emergence of coalition politics is a hopeful sign. Islams role in politics is the focus of Ziad Haiders essay, tracing its evolution from Jinnahs comments through the Munir report, Islamization under Zia and Talibanization to the This is Not Us movement (129) and the hope that moderate Islam represents the future of Pakistan. A chapter entitled Battling Militancy, by Zahid Hussain, continues the discussion, tracing the development of jihadist politics given the situation in Afghanistan. The focus then shifts to economic policy, beginning with Ishrat Husains insistence that economic policies cannot remain sound without solid institutions behind them; he cites the long-term nature of economic progress, while successive governments seem interested only in short-term horizons (149-150). Meekal Ahmed follows the Pakistani economy from the early sixties and periods of relative health, through Ayub Khans era, also a time of economic stability, which changes under Bhutto and his nationalization programs, and since then has gone from crisis to crisis, both the government and poor IMF oversight bearing a share of the blame. Competitiveness is the key concept for Muddassar Mazhar Malik, who reminds us that Pakistan is open for business despite many challenges to overcome, citing economic potential, natural resources and strategic location as strong points (201). Ziad Alahdad then shifts the focus to energy, a sector in crisis which then has an enormous impact on Pakistans economy, all of this in a country with abundant natural energy resources; a more coherent exploitation of Integrated Energy Planning would be part of an overall solution (240). Strategic issues then occupy several chapters, beginning interestingly with education as part of the formula, as advanced by Shanza Khan and Moeed Yusuf, who suggest that politically-neutral education is the foundation not only of

Pakistaniaat : A Journal of Pakistan Studies Vol. 3, No. 3 (2011) economic development but also the means to resist violent extremism by building expectations and supplying hope, especially for the young. Pakistan of course possesses nuclear weapons, and Feroz Hassan Khan asks the question, wondering if its nuclear capability has allowed Pakistan to focus itself on other priorities, in other words averting wars rather than fighting them, to paraphrase Bernard Brodie, cited in Khans essay (268). Munir Akrams essay, Reversing Strategic Shrinkage, highlights Pakistans current challenges: the Pakistani Talibans attacks in KP and large cities; Pakistans involvement in Afghanistan; Balochi alienation; economic stagnation; energy crises; growing poverty, all of which have contributed to a dangerous mood of national pessimism, according to Akram (284). Afghanistan occupies Ahmed Rashids attention, as it has for over thirty years now; he critiques strategic claims that have become worn with time, such as the need for strategic depth for Pakistan (although the notion of strategic depth changes when a country becomes a nuclear power), or Indias desire (among other countries) to gain influence in Kabul (314-315). The final essay, The India Factor, culminates the volume by tracing the tumultuous relations between the two nuclear-armed neighbors, the bumpy road to peace, the effect of the 2008 Mumbai attacks, all within the context of peoples who have not forgotten the trauma of Partition and the secession of East Pakistan. In spite of the obstacles, Syed Rifaat Hussain lists many of the promising agreements that have been reached or are in progress, an encouraging sign and a reminder that good relations are beneficial to both nations. Human development, Maleeha Lodhi remarks in a concluding note, must be Pakistans priority, and is within reach, as all of the contributors to the volume insist. Lodhi summarizes thus: Electoral and political reforms that foster greater and more active participation by Pakistans growing educated middle class will open up possibilities for the transformation of an increasingly dysfunctional, patronage-dominated polity into one that is able to tap the resilience of the people and meet their needs (350). Pakistan: Beyond the Crisis State is a fine piece of work, written by specialists for an audience of intelligent non-specialists, and achieves its objective admirably. Maleeha Lodhi has succeeded remarkably in her edition of this gathering of clear-sighted experts, who never lose sight of Pakistans potential beyond its current challenges.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Volvo FM/FH with Volvo Compact Retarder VR 3250 Technical DataDocument2 pagesVolvo FM/FH with Volvo Compact Retarder VR 3250 Technical Dataaquilescachoyo50% (2)

- 1803 Hector Berlioz - Compositions - AllMusicDocument6 pages1803 Hector Berlioz - Compositions - AllMusicYannisVarthisNo ratings yet

- Harmonizing A MelodyDocument6 pagesHarmonizing A MelodyJane100% (1)

- Mikhail NaemiDocument331 pagesMikhail NaemiCanna IqbalNo ratings yet

- (Evolutionary Psychology) Virgil Zeigler-Hill, Lisa L. M. Welling, Todd K. Shackelford - Evolutionary Perspectives On Social Psychology (2015, Springer) PDFDocument488 pages(Evolutionary Psychology) Virgil Zeigler-Hill, Lisa L. M. Welling, Todd K. Shackelford - Evolutionary Perspectives On Social Psychology (2015, Springer) PDFVinicius Francisco ApolinarioNo ratings yet

- SCIENCE 5 PPT Q3 W6 - Parts of An Electric CircuitDocument24 pagesSCIENCE 5 PPT Q3 W6 - Parts of An Electric CircuitDexter Sagarino100% (1)

- ! Sco Global Impex 25.06.20Document7 pages! Sco Global Impex 25.06.20Houssam Eddine MimouneNo ratings yet

- Form 16 PDFDocument3 pagesForm 16 PDFkk_mishaNo ratings yet

- Cook Pp265-290 StearnsDocument26 pagesCook Pp265-290 StearnsCanna IqbalNo ratings yet

- PCD Jan2011Document2,380 pagesPCD Jan2011Canna IqbalNo ratings yet

- China Has New Political LeadershipDocument6 pagesChina Has New Political LeadershipCanna IqbalNo ratings yet

- Islami Aqeeda-Quran o Hadees Ki Roshni MeDocument71 pagesIslami Aqeeda-Quran o Hadees Ki Roshni MeCanna IqbalNo ratings yet

- The Image of Woman in Pre-Islamic QasidaDocument91 pagesThe Image of Woman in Pre-Islamic QasidaNefzawi99No ratings yet

- Pak Affairs Guess 2013Document2 pagesPak Affairs Guess 2013Canna IqbalNo ratings yet

- 1647 Css NotesDocument262 pages1647 Css NotesCanna IqbalNo ratings yet

- 22 Reasons Why Starting World War 3 in The Middle East Is A Really Bad IdeaDocument5 pages22 Reasons Why Starting World War 3 in The Middle East Is A Really Bad IdeaCanna IqbalNo ratings yet

- E HepC Handbuch Def Kapitel IDocument28 pagesE HepC Handbuch Def Kapitel ICanna IqbalNo ratings yet

- What Is SomatizationDocument3 pagesWhat Is SomatizationCanna IqbalNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Affairs SyllabusDocument1 pagePakistan Affairs SyllabusCanna IqbalNo ratings yet

- Abbas Insists Mideast Peace Deal Must Be - Permanent - (27th Sept 2013)Document2 pagesAbbas Insists Mideast Peace Deal Must Be - Permanent - (27th Sept 2013)Ayma AwaisNo ratings yet

- World Powers, Iran Agree To Resume Nuclear Talks (26th Sept 2013)Document3 pagesWorld Powers, Iran Agree To Resume Nuclear Talks (26th Sept 2013)Canna IqbalNo ratings yet

- Civil Society and Social Change in PakistanDocument43 pagesCivil Society and Social Change in PakistanCanna IqbalNo ratings yet

- World Powers, Iran Agree To Resume Nuclear Talks (26th Sept 2013)Document3 pagesWorld Powers, Iran Agree To Resume Nuclear Talks (26th Sept 2013)Canna IqbalNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Growth and DevelopmentDocument8 pagesAdolescent Growth and DevelopmentMilas Urs TrulyNo ratings yet

- TerrorismDocument4 pagesTerrorismCanna IqbalNo ratings yet

- US Prevented Disclosure of Pakistan - S Rights Abuses - Report (3rd Sept 2013)Document2 pagesUS Prevented Disclosure of Pakistan - S Rights Abuses - Report (3rd Sept 2013)Canna IqbalNo ratings yet

- Waiting For The Tomahawks (5th Sept 2013)Document3 pagesWaiting For The Tomahawks (5th Sept 2013)Canna IqbalNo ratings yet

- War of Attrition As Forces Disappear From Afghanistan (5th Sept 2013)Document3 pagesWar of Attrition As Forces Disappear From Afghanistan (5th Sept 2013)Canna IqbalNo ratings yet

- Pa06 PrenatalDocument32 pagesPa06 PrenatalCanna IqbalNo ratings yet

- 2 Eng KhalilDocument23 pages2 Eng KhalilCanna IqbalNo ratings yet

- US, Iran Talk Nicely, But Nuke Progress Uncertain (20th Sept 2013)Document3 pagesUS, Iran Talk Nicely, But Nuke Progress Uncertain (20th Sept 2013)Canna IqbalNo ratings yet

- US Prevented Disclosure of Pakistan - S Rights Abuses - Report (3rd Sept 2013)Document2 pagesUS Prevented Disclosure of Pakistan - S Rights Abuses - Report (3rd Sept 2013)Canna IqbalNo ratings yet

- Blasphemy - According To Islam and Other ReligionsDocument5 pagesBlasphemy - According To Islam and Other ReligionsCanna IqbalNo ratings yet

- China To Help Deal With Syria - S Chemical Weapons (24th Sept 2013)Document3 pagesChina To Help Deal With Syria - S Chemical Weapons (24th Sept 2013)Canna IqbalNo ratings yet

- The US Is Destabilizing The RegionDocument3 pagesThe US Is Destabilizing The RegionCanna IqbalNo ratings yet

- Morsi's Ouster Shakes Egypt and The Region: Middle East in FocusDocument2 pagesMorsi's Ouster Shakes Egypt and The Region: Middle East in FocusCanna IqbalNo ratings yet

- Discover books online with Google Book SearchDocument278 pagesDiscover books online with Google Book Searchazizan4545No ratings yet

- Network Profiling Using FlowDocument75 pagesNetwork Profiling Using FlowSoftware Engineering Institute PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Adam Smith Abso Theory - PDF Swati AgarwalDocument3 pagesAdam Smith Abso Theory - PDF Swati AgarwalSagarNo ratings yet

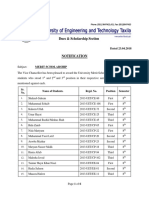

- Dues & Scholarship Section: NotificationDocument6 pagesDues & Scholarship Section: NotificationMUNEEB WAHEEDNo ratings yet

- IC 4060 Design NoteDocument2 pagesIC 4060 Design Notemano012No ratings yet

- Vol 013Document470 pagesVol 013Ajay YadavNo ratings yet

- Henry VII Student NotesDocument26 pagesHenry VII Student Notesapi-286559228No ratings yet

- Bioethics: Bachelor of Science in NursingDocument6 pagesBioethics: Bachelor of Science in NursingSherinne Jane Cariazo0% (1)

- 2-Library - IJLSR - Information - SumanDocument10 pages2-Library - IJLSR - Information - SumanTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Senarai Syarikat Berdaftar MidesDocument6 pagesSenarai Syarikat Berdaftar Midesmohd zulhazreen bin mohd nasirNo ratings yet

- Theories of LeadershipDocument24 pagesTheories of Leadershipsija-ekNo ratings yet

- MCI FMGE Previous Year Solved Question Paper 2003Document0 pagesMCI FMGE Previous Year Solved Question Paper 2003Sharat Chandra100% (1)

- Government of Telangana Office of The Director of Public Health and Family WelfareDocument14 pagesGovernment of Telangana Office of The Director of Public Health and Family WelfareSidhu SidhNo ratings yet

- COVID 19 Private Hospitals in Bagalkot DistrictDocument30 pagesCOVID 19 Private Hospitals in Bagalkot DistrictNaveen TextilesNo ratings yet

- Bhikkhuni Patimokkha Fourth Edition - Pali and English - UTBSI Ordination Bodhgaya Nov 2022 (E-Book Version)Document154 pagesBhikkhuni Patimokkha Fourth Edition - Pali and English - UTBSI Ordination Bodhgaya Nov 2022 (E-Book Version)Ven. Tathālokā TherīNo ratings yet

- Study Habits Guide for Busy StudentsDocument18 pagesStudy Habits Guide for Busy StudentsJoel Alejandro Castro CasaresNo ratings yet

- Surrender Deed FormDocument2 pagesSurrender Deed FormADVOCATE SHIVAM GARGNo ratings yet

- Algebra Extra Credit Worksheet - Rotations and TransformationsDocument8 pagesAlgebra Extra Credit Worksheet - Rotations and TransformationsGambit KingNo ratings yet

- Experiment No. 11 Fabricating Concrete Specimen For Tests: Referenced StandardDocument5 pagesExperiment No. 11 Fabricating Concrete Specimen For Tests: Referenced StandardRenNo ratings yet

- Walter Horatio Pater (4 August 1839 - 30 July 1894) Was An English EssayistDocument4 pagesWalter Horatio Pater (4 August 1839 - 30 July 1894) Was An English EssayistwiweksharmaNo ratings yet

- M Information Systems 6Th Edition Full ChapterDocument41 pagesM Information Systems 6Th Edition Full Chapterkathy.morrow289100% (24)

- Virtuoso 2011Document424 pagesVirtuoso 2011rraaccNo ratings yet

- De Minimis and Fringe BenefitsDocument14 pagesDe Minimis and Fringe BenefitsCza PeñaNo ratings yet