Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Knowledge Management Document

Uploaded by

rajiv2karna100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

409 views0 pagesCDC BITS Pilan MS Course

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCDC BITS Pilan MS Course

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

409 views0 pagesKnowledge Management Document

Uploaded by

rajiv2karnaCDC BITS Pilan MS Course

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 0

(For Internal Circulation)

Distance Learning Programme

M M S S P PR RO OG GR RA AM MM ME E I IN N C CO ON NS SU UL LT TE EN NC CY Y M MA AN NA AG GE EM ME EN NT T

India Habitat Centre

Core - IV B, 2nd Floor, Lodhi Road

New Delhi 110003

November, 2008

1

KNOWLEDGE

MANAGEMENT

2

Contents

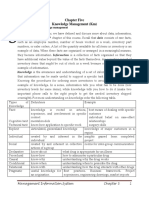

S.NO INDEX PARTICULARS

1. Chapter 1A Introduction to Knowledge Management

2. Chapter 1B Knowledge Cycle: An Overview

3. Chapter 2 Data Information Knowledge

4. Chapter 3 Strategic dimensions of KM; Impact of Business Strategy

5. Chapter 4 Knowledge Management Process

6. Chapter 5 Discussion on Knowledge Use Process: Tacit / Explicit

Knowledge

7. Chapter 6 Introduction to Knowledge Sharing Tools & Techniques

8. Chapter 7

Assignment

9. Chapter 8 Overview of Other KM Tools & Techniques

10.

Chapter 9

Role of it in Knowledge Management

11. Chapter 10 Communities of Practice

12. Chapter 11 Practices of Knowledge Management in Modern Global

Organisations

13. Chapter 12 Measurement Systems for KM

14. Chapter 13 Barriers To Success for KM

15. Chapter 14 Building a Knowledge Management Capability

Framework

16. Chapter 15 Developing a Knowledge Organization

17. References

3

Chapter1A

Introduction to Knowledge Management

Knowledge Capitalism

Wealth and power had traditionally been equated with ownership of physical resources.

Material, labour and money,- the traditional factors of production are physical in nature.

The role of knowledge has been rather limited. The industrial revolution some two and a

half centuries ago was largely facilitated by money capital, labour and steam power.

In contrast, increasingly, wealth and power is being derived mainly from intangible,

intellectual assets knowledge capital.

This transformation from a world largely dominated by physical resources to a world

dominated by knowledge has enormous implication for all of us in this planet. We can

see economic power being shifted from nations with huge physical resources to nations

that largely use knowledge as a factor of production. India and China are being

frequently quoted as examples.

We are as yet in the early stages of knowledge revolution. But the impact is already

becoming apparent all around. The extreme volatility of markets, uncertainty over future

direction within governments and businesses, and the increased insecurity of career and

job prospects are just some examples.

This new economic paradigm has enormous implication on work, jobs, employers, and

employees. In order to comprehend this we need to appreciate how the new economic

paradigm is changing the traditional inputs to wealth creation: materials, labour, and

money.

GOODS AND SERVICES : ROLE OF KNOWLEDGE

Economists and thinkers have been talking of post-industrial society for over a quarter of

a century now. According to the theory of post-industrial society, production of goods

would decline in favour of services. And knowledge would become the basis of economic

growth and productivity, - and occupational growth would largely happen in white-collar

managerial and professional jobs. Data shows that actual trends in economic growth and

employment is quite consistent with these predictions. Employment in agricultural sector

has shown a steady decline in favour of manufacturing and services, in all major

economies Further, between 1970 and 1990, manufacturing employment itself declined in

all G-7 countries : USA, J apan, Germany, UK, France, Canada and Italy.

What is a good and what is a service has not been easy to define. When I buy a CD

with Satyajit Rays immortal film Aparajita - thats a good. But if NDTV 24X7

broadcasts it its a service. Increasingly services sector contributes a larger proportion

4

of GDP. The strong growth of services sector in recent years is linked to the

connection between services and goods-producing sectors. With increased competition,

manufacturers are outsourcing non-core functions to specialist service organizations.

This has seen a decline in employment in manufacturing and a rise in employment in

services.

What is a Service anyway ? Service has been defined as an activity where the output is

characteristically consumed at the same time as it is produced,- having a hair-cut or

riding a cab, for example. But not all services are consumed as they are produced.

Defining service as anything sold in trade that could not be dropped on your foot is as

good as any other definition. When Dell makes a PC as per your specification and

delivers to your home, that is as much a service as a product. When you feel hungry and

order a Pizza with Dominoes, with guaranteed delivery in half an hour, there is a lot of

service built into the product,- pizza.

In fact, as goods and services become more knowledge and information intensive, it

becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish the two. Attempting to distinguish is also

becoming less relevant. Knowledge is the defining characteristic of economic activities,-

rather than either good or service. However we still do not have the tools to measure this

important activity.

KNOWLEDGE: A FACTOR OF PRODUCTION

Knowledge is transforming the nature of production and thus work, jobs, the firm, the

market and every aspect of economy. However, in spite of this, knowledge is as yet a

poorly understood and thus undervalued economic resource. We need to wear different

set of glasses to view the emerging knowledge economy. Older ways of looking at things

is no longer applicable. We need different and new models to predict and plan the future

strategies,- national, corporate or personal whatever. In order to be able to do this, we

first need to understand knowledge and its role as an input to production.

KNOWLEDGE DEFINED

Everyday words like data, information, and knowledge are often used loosely to

describe the same phenomenon. It is good to clear the confusion,- or at least attempt to do

so, as early as possible. Data can be defined as any signals which can be sent from an

originator to a recipient. Information is data which are intelligible to the recipient. And,

finally, knowledge is the cumulative stock of information, and skills derived from use of

information by the recipient. The and which joins the two parts of the previous sentence

has a huge role in clarifying what knowledge is. Knowledge isnt just a stock of

information. It includes skills derived from use of information. Well, we will go deeper

as we move later in this study material. We wanted to have the big picture.

5

Knowledge Characteristics

As this point we are only trying to understand the role of knowledge in economic

activities. However it is good to remember some important characteristics of knowledge.

For one, we must distinguish between knowledge about something, and knowledge about

how to do something what is called know-how.

We could also classify knowledge according to whether it can be made explicit, or

whether it remains implicit or tacit.

It is easy to codify, store, transfer, and share if it is explicit. Not so easy with tacit

knowledge.

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AS AN ENABLER

The change from a physical to an increasingly non-physical information and knowledge-

based economy has been mainly achieved through commercial application of Information

technology. As such, it is good to understand how IT industry has evolved over the

years,- and how it is likely to affect the knowledge economy in future.

Continuously declining cost coupled with improved performance, has meant that

information technology has had a pervasive impact on the overall economy. Information

Systems uses systems analysis and design tools to represent the real world,- trying to be

as accurate and complete in representation as possible. It is thus possible to represent a

complex process, which perhaps describes some knowledge of an individual, through

information systems. It thus enables knowledge to be fragmented into pieces of

information which can be accessed, and if needed, reassembled at low cost. Other

components of information systems would enable this to store , access and transfer the

knowledge models.

It is this ability which enables us to evaluate and use the information, thereby creating

new information. IT therefore plays an important enabling role in creation and transfer of

knowledge. It is in early days, and we will have enough time to spend on these issues

later.

THE CHANGING ROLE OF IT

What we now discuss has an important bearing on the role and importance of knowledge

management. Between the mid-1950s and mid-1980s, as compared to cost of

processing information manually, cost of computing power fell by 8,000 per cent.

In 1900, less than 18% of the total workforce in the USA were engaged in data and

information handling tasks. It had risen to over 50% by 1980. Lets pause for a while. We

said, by around 1980, half of the total work force in USA were in information handling

tasks. If we dissect these information handling workforce, 19% were associated with R &

D, education and training, and design and similar work. Lets remember, these are the

work that can be classified as adding to the long-term knowledge-stock of business. The

6

rest 81% were associated with transient data and information related to day-to-day

operations.

Lets see the trend now. By 2020,- we are now in 2008, it isnt far over 80% of the

work force are likely to be associated with information- handling tasks. Compared to

now, a far higher proportion of these people will be engaged in knowledge building and

decision making tasks. Later in this chapter, we discuss these issues how todays

products and services, because of their complexity, has a much larger knowledge content.

Routine day to day management of information, because of its very nature, and the

capabilities of information technology, will be automated. This factor is pregnant with the

possibility of large scale reduction in work force. Those who remain, need to be much

smarter,- and managing knowledge will be their key focus.

If we follow IT applications in the business area from around early 1960s to date, we

find a clear trend,- the focus of IT has shifted from data processing, to information

management, and further onto knowledge management. During the 60s and 70s main

focus of business was control and standardization through the use of IT. What was

specific to some became general,- tacit knowledge became explicit. 1990s saw massive

spread of networking, linking different functions in an organization first, and then beyond

the organizational borders to customers, suppliers, collaborators etc, and eventually with

internet, networking across the world. This capability dramatically improved access to,

and sharing of information among the various stakeholders which in turn helped to create

a platform for decision support, organizational learning, and knowledge sharing. Routine

functions meanwhile continued to be automated.

Organizations switching to standardized software like SAP R/3 had the effect of leveling.

Viewed from the knowledge perspective, one of the striking features of these

comprehensive and sophisticated commercial application packages, is the extent to

which it provides very comprehensive standards for financial, logistical, and human

resources system, in widely different industrial settings. In one go, with such a system

installed, the organization gets the benefit of a set of best practices for operating many of

the routine functions. While the initial expenses are high, such a system results in lower

operating cost, lower inventory, faster cycle time and so on. Using standardized software,

rather than trying to make one, gives the benefit of knowledge of best practices. There is

a risk though,- the organization may lose firm-specific or tacit knowledge embedded in

the internal processes. However the benefit of the knowledge of the best practices may

far outweigh the loss of such firm specific knowledge.

THE WORLD OF BUSINESS IN AN ECONOMY DRIVEN BY KNOWLEDGE

As we moved into 21

st

century, the world seems to be moving faster and faster. As the

clich goes Change is the only constant. In the rapidly changing business environment,

survival itself is a challenge. There are innumerable areas where this change is visible.

ONE: Larger varieties of products and services. Choices are almost limitless. If your

purse allows, you could have almost anything. Gone are the days of Henry Ford and his

Model T. Though there is some disagreement, most people attribute to Henry Ford the

7

famous words You could have any colour as long as it is black. Trying to make a car

which is affordable at $300 price range, Ford did everything possible to cut down the

cost. This gave birth to the concept of Assembly Line. Ford even restricted his model T

to one colour, that too black,- because it dries up faster and keeps the cost down. Ever

since Maruti Suzuki landed in our country in the early 80s , we have seen a flood of cars

of different makes, sizes, colours and so on.

The picture is same no matter what product or service we are talking about,- Washing

machine, Refrigerator, TV, Insurance cover, Airlines seat, Banking services and so on

and on.

So what can we expect because of this ? Scientists say human behaviour has remained

largely the same. The more you give, more she wants. This leads us to the next factor.

TWO: Demanding customer. With innumerable choices available, each marketer trying

grab your attention you do tend to become choosy. Bargaining is inevitable. Worse, you

look for higher and higher quality as you keep bargaining for lower and lower prices.

Well, thats a pretty good life when we go shopping. But, perhaps life isnt as rosy on the

other side of the table.

THREE: Shorter product life cycle. And we are not talking of microprocessor chips.

Almost any product,- not just TVs, Computers , Music Systems and other electronic

products. With higher disposable income people are looking for newer and newer

products. And whats making all these possible ? That brings us to next point.

FOUR: Rapidly changing technology. Increasingly technology is becoming more and

more powerful,- making it possible to bring out newer products faster and faster at lower

and lower prices. Better and lower cost technology is also making another contribution.

That brings us to next point.

FIVE: Products are becoming increasingly complex. In the mid-70s a washing machine

would have a price of around Rs 600. But what exactly was the washing machine ? A

vertical steel drum with an agitator at the bottom powered by a motor below. All that it

could do is just churn the clothes. We have moved a world from this. Todays washing

machine is a complex one but makes users life easier. With a fuzzy logic and all that it

has a microprocessor inside, build-in intelligence, hardware, software and so on.

Probably 40% ( or more ), of the value of the latest BMW would comprise of

electronics,- hardware, software and so on. So what does it mean for the manufacturer

and marketer ? Expertise in multiple areas. That means more collaboration among

different people.

Fortunately, information technology makes that possible.

SIX: Globalization: Thats the buzz word. Companies have manufacturing facilities

spread around the world, components coming from around the world, markets beyond the

borders, money flowing in the shape of FDI, expertise coming from around the world,

and so on. As Thomas Friedman rightly said,- the world is indeed flat. ( I am referring to

the book The World is Flat by Thomas Friedman, New York Times correspondent. )

8

As one could move beyond borders for market, the same border allows others to come

in. And that makes things difficult for the manufacturer / marketer. That brings us to

competition.

SEVEN: Competition. Increased competition keeps the manufacturer / marketer on their

toes. Trying to survive in this highly competitive world, he needs to bring out newer and

newer products of higher quality at realistic prices. As Akio Morita, President SONY

said If you dont make your own products obsolete, the competition will do it for you.

SPEED IS THE ESSENCE

So what does all these mean to us ? It simply means anything we do, we have less time to

do today than we had yesterday. With the world moving faster, we have less time to

respond. It means faster decision making , faster access to information, increased

collaboration among employees, suppliers, customers etc. With heightened competition,

our researchers must come out with newer designs faster, with better quality. No wonder,

this sweeping changes made Bill Gates title his 1999 book Business @ The Speed Of

Thought . In fact Bill Gates perhaps sums it up in the very first sentence of this famous

1999 book this way: Business is going to change more in the next ten years than it has

in the last fifty. Continuing,- Gates writes later If the 1980s were about quality and

the 1990s were about reengineering, then 2000s will be about velocity. As we see the

business world now in 2008, it is indeed pretty different ,- one might even call it an

impatient, intolerant world. If we have to innovate, come out with newer designs faster,

it does mean there is absolutely no scope for making the same mistake again. If an

engineer in Chicago has struggled for five hours to diagnose and fix a problem, it makes

no sense for his colleague to spend another five hours diagnosing the same problem in

Kolkata. Doing this made no sense ever in history, but today its simply suicidal for any

business organization.

Technology has enabled us to put any kind of information numbers, text, sound, video

to be put in digital form enabling a computer to store, process, and forward it. Handheld

computers ( PDAs ), Cellular phones and of course Internet technology has enabled us to

access information anytime, anywhere.

SERVICE ORIENTED PRODUCT COMPANY OR OTHER WAY AROUND ?

Lets see the impact of heightened speed of activity of business. With an intolerant

customer, business has little time to react. When a manufacturer ( or, for that matter a

retailer ) has to respond to market changes in a matter of hours, rather than days or weeks

available earlier, is he a Product company with service attached to it, or, a Service

company that has a product to offer ? Or, for that matter, when Dell allows a customer

to design his PC as per his needs, and then makes the PC and ships to his customer,-

does it look like just a product or far more ? These are indeed serious thoughts that

come to mind when we look at business today. Things look topsy-turvy.

9

HIGHER CONTENT OF KNOWLEDGE

It had always been true that in a typical business organisaion the middle and higher level

executives had been largely involved in processing information. These were typically

operational information like sales data, inventory status, production data, costs and so on.

Typically the products too were far less complex. This essentially meant that the

knowledge content in employees work were limited. However, increasingly things

seemed to be changing rapidly. The complexity of the environment in terms of

globalization, competition, intolerant customer, rapid change in technology particularly

after the advent of internet, global connectivity, low cost of computation, powerful

software tools for analysis, software for collaboration etc. has completely changed the

character of business,- the very way business is done. This has meant a shift in the nature

of work a typical employee does. The fact that products have higher technology input

itself means that you need people who are smarter, can handle complex products,

complex situations and all ,- in short he has to handle situations that are just not routine.

Increased competition means faster response to market signals, customer feed back,

technology changes etc. This again raises the level of work to more thinking type.

Intolerant customer means faster action which in todays world may mean more group

work.

In this changing scenario, economic activity is shifting from physical goods to

information-based products. For instance, increasingly we need to carry less and less of

currency and coins for any purchasing done. This is done through credit / debit / (smart

cards where the information regarding the money available is stored ).

For employees at the shop floor too, it is no longer the dull repetitive activity that was

best represented by Henry Fords Assembly line. Today the work is far more process

oriented, that requires action from multiple persons.

Lets take the case of DELL when they changed the process of manufacturing. In the

typical assembly line situation, there were 22 people through whom raw material and

intermediate products were moved before it came out as a final product. The new process

at DELL made it possible to manufacture a PC as per customers specification, and

assembled by just two persons sitting in front of terminal, guided by software.- a PC with

all software installed and fully tested. This job is far more enriching than the assembly

line case of each person fixing just one component. In turn , this job requires people who

are more educated, better trained and so on.

I had mentioned the case of a washing machine. As an appliance, - this product today

has a lot of technology built into it to make it an user friendly. A lot of money, research

effort etc has gone before building this product. Actual manufacturing cost may not be

high.

Or, take the case of an air-conditioner. Early model air conditioners had an on-off switch,

a rotating knob for lower or higher cooling, and another to control air speed.

10

As I write this material, Delhi city is flooded with advertisements of a new Hitachi air

conditioner. Hitachi Home and Life Solutions ( India ) Ltd at their website www.hitachi-

hli.com announces the new air-conditioner with the following :

Presenting for the first time ever, an air-conditioner that relieves you from

uncomfortable sweat.

HITACHI ACE WITH AUTO HUMID CONTROL

Air-conditioning is not just about cooling, it's more about comfort. An average human

being feels comfortable with the right blend of temperature, air-flow & humidity control.

Conventional air-conditioners may provide the requisite temperature & air-flow but fails

to control the rising humidity levels alongside. Thereby with your conventional air-

conditioner, you struggle to find the desired comfort level and despair with the rising

heat and sweat.

Lets look at it again: Air-conditioning is not just about cooling, it's more about

comfort.

Here is an AC that not only cools ( that was the primary reason so to say ), and controls

air-flow, but manages the humidity as well. In order to build more and more intelligence

into our products we spend more on design aspects. While from user point of view it is

easy, product itself is complex. What it all means is that of the total product cost, the

proportion of raw material and manufacturing cost is lower these days. Much of the

expenses have been incurred before. Whether you are a research engineer or a repair

mechanic, knowledge content is higher.

Another trend,- products customized to individual needs,- is increasingly visible. This is

to satisfy customers,- who seem to be asking for more and more all the time. DELL did it

Levi Strauss does it and a lot more,- Nike at one end,- BMW at the other. When we

move from mass produced to mass- customized products we can easily see the higher

knowledge content in the product. We talked of DELL earlier.

With increased competition, manufacturers and producers of goods and services have

realized that latching on to an existing customer, and giving and satisfying him with

value-added products with higher margins is a better proposition than offering mass-

produced goods to one and all. This necessarily requires the company to know his

customer profile better which needs use of lot of analytical tools, and thus much

knowledge-based.

As contribution of knowledge towards production of economic wealth increases,

economies that were largely natural physical resource-based,- for instance Australia,

seem to be slipping in the table of nations with highest per capita income. It is perhaps

no charity that such nations,- Australia, Canada and many other countries, have easier

immigration laws for people with higher skills. Much advertised, discussed, and debated,-

United Kingdoms Highly Skilled Migration Programme (HSMP) is one such.

11

To survive in this highly technology oriented, innovation focused economy,- even USA is

encouraging easier immigration for people with better education and research skills.

Microsofts Bill Gates was one among the many top CEOs to plead with Clinton

government to increase H1B visa.

KNOWLEDGE SHARING

With little time to react, organizations are compelled to rediscover that it makes

enormous sense to share what employees know, and thereby increasing what Bill Gates

term Organisational IQ. If we share what we know with our colleagues the total of what

the organization knows is much more than what an individual does. For instance, if what

I know is X and what you know is Y , and if you share with me what you know then I

will know X+Y which is more than X. Similarly if I share with you what I know, you

would know Y+X which is more than Y.

This seems pretty different ball game all together. If two brothers divide their ancestoral

land of 5 bighas, each will have 2.5 bighas. If I have thousand rupees, and give you two

hundred, I am left with eight hundred only. So unlike other factors of production like

land, labour, capital where sharing results in reduction , or depletion, sharing of what I

know results in increment of what you know.

Now, whats the best way to describe what I know ? Assume I know the following ( Its

all in my head ):

a) Name of the worlds highest mountain peak

b) How to fix Windows booting problem

c) Name of the largest circulated English daily in India

d) How to eat with my hand

e) How to make a Chapatti or a Romali roti.

f) What is Knowledge Management

g) The Sun rises in the east.

h) How to eat fish without the bones getting stuck in the throat.

i) How to ride a bicycle

This is what we could call Knowledge. The more one knows such things the more

Knowledgeable he is.

This is apparent that sharing some of this knowledge is easy,- namely which is the largest

circulated English daily in India. However it wont be that easy to share the knowledge

how to make a romali roti. Or, what is knowledge management But more on this later.

Lets pause for a while and try to figure out what that illusive term knowledge means.

Without becoming bookish, one could attempt to define Knowledge as a mix of

accumulated experience, values, contextual information, insight and intuition that enables

one to evaluate new experiences and information. It originates and is applied in the minds

of knower. In an organizational context, knowledge often becomes embedded not only in

documents or repositories but also in organizational systems and procedures.

12

Now, let us get back to what I know or my knowledge.

Name of the worlds highest mountain peak,- Mount Everest , Largest Circulated English

daily in India The Times of India ( an on date of writing this material ), The Sun rises in

the east these are all facts. This is what is called explicit knowledge or formal

knowledge. We could easily write it on a piece of paper or store in a computer.

Now, let us look at some other knowledge. How to eat fish without the bones getting

stuck in throat is something that even a ten year old Bengali boy ( or girl for that matter !!

) knows. But is that something that one could describe in a piece of paper ? Or, take the

example how to ride a bicycle. No matter how much we might try, it is impossible to

write a one page, easily understood document that would teach a young child and help

him or her understand how to ride a bicycle. It would be hard to transcribe into a

document feelings such as confidence and balance. This is what is called embodied

knowledge, or informal or tacit knowledge.

The key distinction is we could store explicit knowledge or formal knowledge in a piece

of paper or computer storage. Implicit or embodied knowledge is personal. Its all in the

head !!

As I was writing this material, I saw an interview on NDTV 24X7 with the rather

controversial British Author J effrey Archer who has sold millions of copies of his books.

Someone in the audience asks How do you write ? referring to the beautiful

expressions in his books. And what do you think was J effrey Archers answer ? I dont

know I wish I knew he says. Elaborating further he says,- If you asked Sachin

Tendulkar,- one the greatest batsman on planet according to his admission- how he

manages to bat so well, - could he explain? Perhaps no. This is simply God-gifted. So,

there it is. Some knowledge is simply not describable.

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

It follows from whatever we discussed so far that indeed it makes sense to collect the

knowledge and expertise available with people in the organization, store it and share

with people who need them to enhance the overall competence level of the organization

which is a necessity in todays competitive world. This is what knowledge management

is all about. There are a lot of technical tools available to assist in this tapping, coding,

storing and sharing efforts. A lot of people tend to equate KM with these technical tools.

But in reality, while these tools are a necessary ingredient of KM, KM is far more. We

will delve into these deeper as we move along.

Back

13

Chapter 1B

KNOWLEDGE CYCLE: AN OVERVIEW

Knowledge management ( KM ) is a process that helps organizations to identify, select,

organize, disseminate and transfer important information and expertise that are part of the

organisations memory.

In simplest terms knowledge cycle refers to the repetitive process of gathering knowledge,

organize it by codifying, indexing etc, and finally sharing or making it available for use by

employees. Fundamental point to realize is that its a virtuous circle increasingly refined

and of higher value to the organization.

KNOWLEDGE CYCLE: DEFINITION

A quick recap of what knowledge is. Knowledge is the cumulative stock of information,

and skills derived from use of information by the recipient. While data refers to

individual, unconnected facts,- information is data organized in a specific way for a

definite purpose, knowledge is information in action in the context of personal

experience.

Information could reside anywhere,-paper, computer storage and of course in the mind.

Knowledge is based on information, but primarily consists of continually evolving skills

and experiences of an individual or a group.

Knowledge Management System Cycle

A functioning knowledge management system follows six steps in a cycle. The reason

why it is a cycle is simple. Knowledge is never static. It continually gets refined and

upgraded. In a good knowledge management system knowledge is never finished because

the environment changes over time, and knowledge must be updated to reflect these

changes. The cycle works as follows:

1. CREATE KNOWLEDGE : Knowledge is created as people find new ways of

doing things. Often external knowledge is brought in,- some of these could be

best practices.

2. CAPTURE KNOWLEDGE: New knowledge must be identified as valuable and

be represented appropriately.

3. REFINE KNOWLEDGE: New knowledge must be placed in context so that it is

actionable. This is where insight ( tacit knowledge ) must be captured along with

explicit knowledge.

14

4. STORE KNOWLEDGE: Useful knowledge is stored in a format in a knowledge

repository so that other people in the organization could access it.

5. MANAGE KNOWLEDGE: J ust as a library must be must be kept current,

knowledge must be continually reviewed to see that it is current, relevant, and

accurate.

6. DISSEMINATE KNOWLEDGE: Make the knowledge available to anyone who

needs it.

With proper dissemination of knowledge, individuals develop, create and identify new

knowledge or update old knowledge which they replenish into the system.

It must be noted that knowledge as a resource is never consumed when used, though it

can age. Knowledge must be updated. Knowledge grows with time.

MYTHS ABOUT KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

Like the learned Professor of Economics who got completely bewildered with the term

Knowledge Management, there are others who perhaps have a narrower view of KM. Like

as we said a little while before: KM is just Technology.

While in the early 1990s the whole business world were talking about Reengineering, a

few years later when KM came, people wrongly assumed it as reengineering by another

name. Reengineering is about dismantling and making it over again with new thinking. It is

all about changing the process to make it simpler, enabled by information technology.

Moreover, with reengineering it is a one-shot affair. In contrast KM is an ongoing

continuing thing.

15

Its a new concept- some would think,- which it is not. Organisations have used it for long,

except that newer technologies have enabled it on a scale and at a level that was simply not

possible earlier. IBM for instance, - a company that was known for its service, had a system

where customer engineers would report difficult problems, their diagnosis, and solutions.

Collected from around the world, experiences like this would be circulated all over the

world for sharing by other customer engineers. Only thing, this was in paper form, of

course. Incidentally, IBMs customer focus,- a much talked about topic today was visible

even from the designation it gave to its engineers Customer engineer. They were not

designated Service engineer or something similar.

KM is just data warehouse a place where lot of business data is stored ,- thats another

incorrect impression. As we will see in later chapters, todays technology tools provide

extremely complex analytical ability to know about a problem, to know the customer, his

likes dislikes etc. much better. These are fairly recent developments.

IMPORTANCE OF KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

As early as September 1943 in a speech delivered at Harvard University Sir Winston

Churchill said -- The empires of the future are the empires of the mind. Remember

1943, peak of world war II,- its the time when manufacturing drew all the attention.

And, - the sun never sets in British empire, -thats what was a popular saying.

Much before the term Knowledge Management gained currency, noted industrialist

Andrew Carnegie said,- The only irreplaceable capital an organization possesses is the

knowledge and ability of its people. The productivity of that capital depends on how

effectively people share their competence with those who can use it. Late Peter Drucker

who needs no introduction, wrote The basic economic resourcethe means of

productionis no longer capital, nor natural resources, nor labor. It is and will be

knowledge.

Knowledge as a resource has always been valued. It is only that changes in business

environment and technology has made it inseparable from survival. Even Charles Darwin

wrote:

In the struggle for survival, the fittest win out at the expense of their rivals because they

succeed in adapting themselves best to their environment.

In recent times authors after author have emphasized on KM. One of the best known

authority has to say the following:

In the rapidly changing social, political and economic environment,-disruptive change,-

as it is often referred to , survival depends on Knowledge, or to be more specific

application of knowledge. ( Yogesh Malhotra )

16

In the path-breaking article The Knowledge-Creating Company ( HBR ) Ikujiro Nonaka

writes:

In an economy where the only certainty is uncertainty, the one sure source of lasting

competitive advantage is knowledge.

Today, the ability of an organization to stay current and stay relevant requires a core

competence in Knowledge Management. Organisations need to respond to social and

economic trends. Three major drivers of change are: globalization, ubiquitous computing,

and the knowledge-centric view of the firm.

Perhaps the biggest factor is globalization. The complexity and volume of global trade

today is unprecedented; the number of global players, products, and distribution channels is

much greater than ever before.

Information technology has speeded up all the elements of global trade. This, coupled with

the decline of centralized economies have created an almost frenetic atmosphere within

firms, which feels compelled to bring new products and services,- catering to a wider

market - much faster than ever before. The combinations of global reach and speed has

compelled the organizations to ask themselves what is it that we know, who knows it, and

what is it that we dont know but we should know.

To sum it up knowledge, and its management is important today more than ever before

because:

Globalization leading to extreme competition , outsourcing products & services beyond the

core competence, mergers & acquisitions, never ending drive to accelerate product

development, - all these factors forces organizations today to tap into resident knowledge

more urgently than ever before.

Technological tools are available today to:

1. Facilitate knowledge sharing through centralized depositories of information

2. Enable real-time collaboration through electronic workplace

3. Help identify experts and expertise with intranet-based location systems

Need for Knowledge Managements: Some Specifics

If we look around, we can see a number of common situations that seem to be immensely

benefiting from knowledge management approaches. While it is obvious that these are

not the only issues that can be tackled with KM techniques, it is useful to explore a

number of these situations. This would provide us a context for the development of a

KM strategy. Beyond these typical situations, each organisation will have unique issues

and problems to be overcome.

17

Call Centres

Pressures of competition have forced organizations to open Call centres that have

increasingly become the main 'public face' for many organisations. Heightened customer

expectation to get response to their queries has made the role of Call Centres much more

challenging.

Other challenges confront call centres, including

high-pressure, closely-monitored environment

high staff turnover

costly and lengthy training for new staff

In this environment, the need for knowledge management is clear and immediate. Failure

to address these issues impacts upon sales, public reputation or legal exposure.

Front-line Staff

Many organisations have a wide range of front-line staff who interact with customers or

members of the public on a regular basis. They may operate in the field, such as sales

staff or maintenance crews; or be located at branches or behind front-desks.

In large organisations, these front-line staff are often very dispersed geographically, with

limited communication channels to head office. Typically, there are also few mechanisms

for sharing information between staff working in the same business area but different

locations.

The challenge in the front-line environment is to ensure consistency, accuracy and

repeatability.

Business Managers

Todays managers are flooded with information. The volume of information available

has increased greatly. Faced with 'information overload' or 'info-glut', the challenge is

now to filter out the key information needed to support business decisions.

The pace of organisational change is also rapidly increasing, as are the demands on the

'people skills' of management staff. In this environment, there is a need for sound

decision making. These decisions are enabled by accurate, complete and relevant

information.

Knowledge management can play a key role in supporting the information needs of

management staff. It can also assist with the mentoring and coaching skills needed by

modern managers.

18

Aging Workforce

Many public sector organizations are particularly confronted by the impacts of an aging

workforce. Private sector organisations are also recognising that this issue needs to be

addressed if the continuity of business operations are to be maintained.

People who have been long in the organization have a depth of knowledge that is relied

upon by other staff. This is particularly so in environments where little effort has been

put into capturing or managing knowledge at an organisational level. In such a situation,

the loss of these key staff can have a major impact upon the functioning of the

organisation.

Knowledge management can assist by putting in place a structured mechanism for

capturing or transferring this knowledge when staff retire.

Supporting Innovation

Faced with extreme competitive environment, many organisations have now recognised

the importance of innovation in ensuring long-term growth, or even survival. This is

particularly true in knowledge-intensive sectors such as IT, consulting,

telecommunications and pharmaceuticals.

Traditionally, most organisations, however, are constructed to ensure consistency,

repeatability and efficiency of current processes and products. Innovation is not in their

focus. As such, organisations need to look to unfamiliar techniques to encourage and

drive innovation. Knowledge management can significantly contribute to process of

innovation.

Challenges:

There are challenges to implementation of KM systems. One, employees need to

acknowledge that what is in their head is valuable. Two, and more importantly,

management has to convince employees that the best way to develop that value is to share

what they know among others.

More on this later, towards the end of this study material,- under title Barriers to success

for KM.

READINGS SOURCE:

http://www.fujitsu.com/za/services/consulting/knowledge/mobilising/

Accessed 16.06.2008

Mobilising Knowledge Explained

There are two basic forms of knowledge:

That which resides in our heads which we call Tacit Knowledge

19

That which is written down and stored in forms that are accessible, which we call

Explicit Knowledge

Research over the past few years have concluded that something between 50% and 85%

of the knowledge in an organisation is tacit, i.e. only available through people. Other

research has also shown that much of the explicit knowledge is inaccessible - locked in

systems that people cannot readily get at it.

The Value of Different Forms of Knowledge

The text below shows some of the differences in value associated with these two forms of

knowledge

Tacit Knowledge

Ability to adapt

o to deal with new and exceptional situations

o expertise

Ability to collaborate

o to share a vision

o to transmit a culture

o to coach

Explicit Knowledge

Ability to disseminate

o to reproduce

o to access and re-apply

o to teach

Ability to systemise

o to articulate a vision and translate it into operations

o to integrate into products, services and processes

Given these two forms of knowledge, then there are four associated transformations. We

can transfer knowledge between us across the table, in meetings, around the coffee

machine, etc. This is defined under the heading of Socialisation and has many

advantages, primarily that it is personal and can be adapted to suit the circumstances and

the understanding and responses of those listening. However, outside of the exchange,

nobody else gets to know anything.

So we can capture the knowledge so that it can be made available to a much wider

audience. This is known as Externalisation. Whilst this enlarges the recipient knowledge

base, the downside is that the lack of personal interaction may lead to misunderstandings

and misinterpretations.

20

Once knowledge is captured, there is an opportunity to classify it and combine it with

other knowledge. The trend in the sales figures can now both be seen and associated with

other factors, such as sales resources, seasonal buying peaks and troughs, etc. It is often

in the process of Combination, that we truly extract knowledge from what was previously

really just information.

But the truth is that we don't ever really use explicit knowledge directly. In order to use

knowledge we have to internalise it. For instance, if you are driving along the motorway

and someone pulls out in front of you, it's no good having to look in the glove

compartment for the manual (explicit knowledge) on how to avoid an accident - you must

have that knowledge internalised.

Knowledge is typically fed around the loop through further tacit to tacit exchanges in a

continual spiral of evolving knowledge. The model is shown diagrammatically below

The Four Knowledge Transformations

Based on: The Knowledge-Creating Company, Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995.

In mobilising knowledge, one has to consider a holistic view taking account of four

important dimensions:

1. People: This needs to address such aspects as personal motivation, a possible

recognition programme and incentives for knowledge sharing

21

2. Processes: This should address such issues as Knowledge capture,

validation/approval of content and removal of out of date content

3. Organisation: The overall organisation associated with any programme for

mobilising knowledge will be a critical aspect in achieving success. Specific roles

and policies are required

4. Technology: Technology underpins the programme and helps deliver knowledge

to those who (re-)use it

In mobilising knowledge it is also critically important to understand the knowledge cycle.

The diagram below shows key elements of the knowledge cycle but it is very important

to read it the correct way. Start on the left at Use and work your way back anti-clockwise

to the top. Too many people start by trying to identify, capture and create knowledge so it

can be stored for re-use. This is a recipe for failure. One must start by asking what

knowledge is likely to be useful and then implement solutions that help to capture and

store that knowledge for sharing. Otherwise, you are likely to end up with a store of

knowledge that no-one uses.

The Knowledge Cycle

The focus of mobilising knowledge is always around the value that can be achieved.

Consequently, it is key to deliver the knowledge at the 'Point of Performance'. The

picture below highlights this crucial point by placing the user in the centre of our

consideration and the shows the types of knowledge that user may find of value in their

business of employee roles in respect of the processes they undertake.

22

Delivering Knowledge at the Point of Performance

In summary, to mobilise knowledge effectively one must:

address the management of the four types of knowledge transformation, cover the

four dimensions and service the full knowledge cycle

focus on the value to be delivered by concentrating on delivering knowledge at

the 'Point of Performance

in addition, one must build on, and incorporate associated domains of activity:

o Content Management (CM), historically a system used to manage the

content of a Web site, with a focus on the managing for presentation but

now more about managing and providing access to relevant content across

the Enterprise - Enterprise Content Management (ECM)

o Document Management (DM), which helps manage the entire life cycle

of a document, from creation, through multiple revisions to final version

o Records Management (RM) which covers the creation and

implementation of systematic controls for records from their creation or

receipt through to final disposal or archive.

Back

23

Chapter 2

DATA INFORMATION KNOWLEDGE

Data Information Knowledge,- very common terms indeed. We use them everyday in

our conversations. But do we really understand the meaning of each, and how they differ

from each other? Between Data and Information there is often a bit of confusion,- in fact

we tend to use one for the other sometimes. As regards Knowledge, well we understand it

is something with much deeper, much wider meaning. But if we are asked to define

Knowledge most of us would fumble looking for words to express it. But I suppose

we can forgive each other for not being able to do so,- simply because there isnt an

agreed definition. Indeed the word Knowledge seems a bit hazy. But trying to

understand what Knowledge management means, and how it could be useful in

organizations, we do need to clear the haze,- first things first.

Lets make an attempt. Commonsense suggests that we begin with a more familiar

territory, - DATA.

As we all know, data is a collection of discrete objects, facts or events,- but has no

context. Data is represented in the form of a text, numbers, audio, video, images, or any

combination of these. We could collect data in many ways. For instance, surveys,

interviews, the use of sensors and so on. The blood pressure instrument the doctor uses

thats a way to collect data regarding a persons blood pressure. ECG

(electrocardiogram) is a test that measures the electrical activity of the heart. In an ECG

test, the electrical impulses made while the heart is beating are recorded and usually

shown on a piece of paper. This is known as an electrocardiogram. By itself it has no

meaning. This is data.

Or, let us say, when we buy something from the store, as we check out the transaction

gets recorded. That is Data. When an organization buys something, sells something,

produces something,- it all gets recorded. Someone is present or absent from office, that

gets recorded. Thats all data. But by itself it doesnt mean anything. Rainfall data for all

365 days of year for the last 50 years for Delhi city, available with the met department,-

again thats data. Primarily, it doesnt carry any meaning no matter how large the

quantity of data is.

In order to get a meaning, we need to process the data. When we process the rainfall data

we may find that long-term average rainfall in Delhi in the month of May is 17.5 mm.

Now thats something useful to us. We call it Information. Basically Information is

processed data. For instance, the recorded sales data of the store, when processed

appropriately gives product wise, category wise daily sales. Thats meaningful to the

store owner for decision making,- for instance whether to reorder the items sold. We need

to categorise and summarise the data. In order to convert data into information the

following steps are involved:

24

- Collect data

- Classify

- Sort / merge

- Summarise

- Store

- Retrieve

- Disseminate

Depending on what we want to do, some or all of the above steps may be required to

convert data to information.

In the early days of computing, if we recollect, we used to call this process Electronic

Data Processing ( EDP ). The emphasis was on quantity of data. In the enthusiasm of

processing the data and distributing the reports, the bigger picture often got lost. Those

tons of paper got distributed to any number of managers in the organization. Trying to

process huge data through not so fast and convenient computing devices, the word

relevance was in the back seat. Often the report would be so delayed that from

managerial point of view it would lose relevance. A marketing manager could hardly

react if the sales figure is four months old.

We have moved a world from this picture. Todays computing devices are enormously

fast, and collecting data has become extremely easy. For instance, going back to grocery

store example, as the sales assistant flashes the bar code scanner on the Universal Product

Code stuck on the packet, the store collects a huge lot of information like whats the

product, its price, quantity, the time this transaction was done and so on. But the point is

no matter how voluminous the collected data is, it has little value to the store owner

unless he has the bigger picture,- the context.

Lets see if we can make some sense out of it. By processing the data, the store can figure

out the number of transaction carried out during different time periods of the day, week

etc. The store owner can now use this information to decide how many counters for check

out should be kept open during what time period. He could optimize the customer queue

to increase customer satisfaction, and yet save on salaries to sales assistants.

I believe we now realize that while raw data is necessary and important, in order to be

useful to us we need to convert it to information by putting appropriate context to it.

Whats Information for one is sheer garbage for another.

I had often seen my daughter play what she calls music while studying seriously for her

exam. To me its sheer noise. I would often ask her to reduce the volume at least, if she

wouldnt stop that music all together. To me,- I would much like to play a Tagore song

( Rabindra sangeet ). Thats something I enjoy. But to my daughter, being born and

brought up at Delhi those Tagore songs are too slow kind of stuff. So it is,- what is

information to one could very well be sheer garbage , noise to others. That piece of

recordings of Tagore or, whoever, is Data. No argument on that. But is that relevant,

25

does it have a purpose ? As I and my daughter raise this question the answer isnt same.

As Drucker rightly said information is data endowed with relevance and purpose.

In our journey from a familiar ground of data to information to a rather cloudy area of

Knowledge, we are now around half way. I am saying almost half way because the travel

from data to Information is comparatively easier task,- not so as we approach

Knowledge.

KNOWLEDGE

Unsure of what it means I did what anyone else would do. I opened the dictionary, -

Oxford dictionary for that matter. This is what it has to say against Knowledge: 1.

Knowing, familiarity gained by experience 2. Persons range of information 3. theoretical

or practical understanding ( of a subject, language etc.)

In an age of web I wanted to explore how others look at the word knowledge. Following

is only a sample:

Knowledge is part of the hierarchy made up of data, information and knowledge. Data

are raw facts. Information is data with context and perspective. Knowledge is

information with guidance for action based upon insight and experience.

Lets pause for a while. Knowledge is part of the hierarchy made up of data, information

and knowledge.

This view looks at it as a continuum from data to information to knowledge.

Next sentence says:

Data are raw facts. Information is data with context and perspective.

As we said, information has a context, a perspective. Thats how it becomes meaningful.

And we can see, knowledge has something to do with experience, insight. Information

backed with experience and insight becomes knowledge. Even the Oxford dictionary

refers to knowledge as familiarity gained from experience.

Important point is knowledge needs interaction with the world,- and we dont intend to

get philosophical -thats how experience is gained. That learning from experience is what

is stored in the mind, and is called knowledge. At the organisatioal level, knowledge is

stored in the minds of employees. Knowledge can also be stored in diagrams, blueprints,

books and such physical media.

We could define knowledge as a mix of experience, values, contextual information, and

expert insight that provides a framework for evaluating and incorporating new

experiences and information. This definition suggests that knowledge is something that

grows with time.

26

A distinguishing factor between information and knowledge is that knowledge has a

connotation of action. While information by itself does not lead to action, knowledge

does. In the context of an organization, knowledge is what employees know about their

customers, about their products, processes, the mistakes they made, as also the success

stories.

An interesting thing about knowledge assets is that while conventional material assets

decrease as they are used, knowledge assets increase with use. When you share your

knowledge with somebody, you dont lose anything while the receiver is enriched. Ideas

breed new ideas in a spiraling fashion.

CHARACTERISTICS OF KNOWLEDGE

1. Extraordinary leverage and increasing returns:

Knowledge is not subject to diminishing returns. When it used, it is not consumed. It

doesnt get reduced. Users of Knowledge can add to it thereby increasing its value.

2. Need to refresh :

Knowledge is dynamic, it is information in action. As environment keeps changing,

some knowledge gets obsolete while we add new knowledge and skills. Thus

organizations must continually refresh its knowledge base to be able to use as a

competitive advantage.

3. Uncertain value:

This is very peculiar about knowledge. It is difficult to estimate its value. While a

particular knowledge is extremely useful to company A , it could be totally useless to

company B. This characteristic is so different from other material assets. A piece of

furniture would have a price that wouldnt vary too much.

To give an example, while companies hire people, those who dont get selected often get

a letter like this : We regret we do not have a vacancy suitable to your qualification and

experience . The same applicant gets an offer from another company perhaps at a

multiple salary of the previous one. It all depends on how your knowledge is valued by

the company.

Till a few years back students with Statistics background,- very bright minds indeed,

werent valued much by corporate world. Today Google would hire these bright students

at fabulous salaries simply because their knowledge of Statistics is of enormous value to

Googles search efforts.

4. Knowledge has context

5. Knowledge resides in knower

27

Dimensions of knowledge

A key distinction made by the majority of knowledge management practitioners is

distinction between tacit and explicit knowledge. Tacit knowledge is often

subconscious, internalized. The individual may or may not even be aware of what he or

she knows and how he or she accomplishes particular results. At the other end of the

spectrum is conscious or explicit knowledge -- knowledge that the individual holds

explicitly and consciously in mental focus, and may communicate to others. To a layman,

tacit knowledge is what is in our heads, and explicit knowledge is what we have codified.

Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) argued that a successful KM program needs, on the one

hand, to convert internalized tacit knowledge into explicit codified knowledge in order to

share it, but, on the other hand, it also must permit individuals and groups to internalize

and make personally meaningful codified knowledge they have retrieved from the KM

system.

The focus upon codification and management of explicit knowledge has allowed some

knowledge management practitioners to appropriate prior work in information

management. This has led to the frequent accusation that knowledge management is

simply a repackaged form of information management.

Critics have argued that Nonaka and Takeuchi's distinction between tacit and explicit

knowledge is oversimplified and that the notion of explicit knowledge is self-

contradictory. Specifically, for knowledge to be made explicit, it must be translated into

information (i.e., symbols outside of our heads).

Another common framework for categorizing the dimensions of knowledge discriminates

between embedded knowledge as knowledge which has been incorporated into an artifact

of some type (for example an information system may have knowledge embedded into its

design); and embodied knowledge as representing knowledge as a learned capability of

the bodys nervous, chemical, and sensory systems. These two dimensions, while

frequently used, are not universally accepted.

It is also common to distinguish between the creation of "new knowledge" (i.e.,

innovation) vs. the transfer of "established knowledge" within a group, organization, or

community. Collaborative environments such as communities of practice or the use of

social computing tools can be used for both creation and transfer.

TYPES OF KNOWLEDGE

Knowledge is of two kinds Explicit and Implicit. While we try to distinguish between

them, we need to remember that the distinction is a bit blurred. We will soon see how.

Explicit knowledge: It is the visible knowledge available in the form of letters, reports,

memos, literatures, etc. It can be easily explained and stored in computer databases.

Explicit knowledge can also be embedded in objects, rules, systems, methods etc.

28

Tacit knowledge: Tacit knowledge is confined in the mind of a person, and hence is

highly invisible . It is hard to capture and therefore, difficult to communicate to others.

Lets take an example. A master craftsman after years of experience develops a wealth of

expertise. As we often say Its all in his finger tips. But would he be able to articulate

the scientific or technical principle behind what he knows? Perhaps no. Transforming

knowledge from tacit to explicit form makes it visible and usable. However, capturing the

experts tacit knowledge that resides within him in the form of know-how and insights is

indeed a very difficult and challenging task. Roomali roti how to make,- only the man

who makes it knows. Can he describe in detail? Perhaps no. Or, lets go back to fish.

How does one eat fish without the bones getting stuck in throat ? Trust me even asking

a Bengali wont help. He eats it everyday morning and evening,- but he just cant

explain.

As I said earlier, clearing the hills of Data and Information is easier. But it is very

cloudy and hazy when we reach Knowledge. We have dissected knowledge into explicit

and tacit. But is the dividing line clear ? We said explicit knowledge is something that

could be put on a piece of paper and therefore easily transferable. How about process

diagram of an oil refinery ? Or, the logic diagram of a computer ? To understand

completely such a written document, which we said is explicit knowledge, it often

requires a significant amount of experience i.e. tacit knowledge. It needs a background in

engineering.

Knowledge Creation Process - SECI Model

According to Professor Ikujiro Nonaka, knowledge creation is a spiraling process of

interactions between explicit and tacit knowledge. The interactions between the explicit

and tacit knowledge lead to the creation of new knowledge. The combination of the two

categories makes it possible to conceptualize four conversion patterns.

Knowledge created in an organization through the process of interaction of tacit and

explicit knowledge. It can't be just one way or the other. The knowledge creation happens

by different linking processes of these two types of knowledge in the organization. The

process of knowledge creation is a continuous one. As knowledge is created between

individuals, or between individuals and the environment, individuals transcends the

boundary between self and others. As per Ikujiro Nonaka there are four types of

knowledge creating process.

1. Socialisation

2. Externalisation

3. Combination

4. Internalisation

29

SECI MODEL

Socialization

New knowledge is created through the process of interactions, observation, discussion,

and so on. Basically, this mode enables the conversion of tacit knowledge through

interaction between individuals. One important point to note here is that an individual can

acquire tacit knowledge without language. It happens by analyzing what is observed.

Apprentices work with their mentors and learn craftsmanship not through language but

by observation, imitation and practice. It is like in traditional environments where son

learns the technique of wood craft from his father by working with him and not from

reading books or manuals. By the way, in the Indian context, much of the traditional art

and craft are dying simply because the traditional family no longer exists In a business

setting, on job training (OJ T) uses the same principle. The key to acquiring tacit

knowledge is experience. Without some form of shared experience, it is extremely

difficult for people to share each other thinking process.

The tacit knowledge is exchanged through joint activities such as being together,

spending time, living in the same environment rather than through written or verbal

instructions.

In practice, socialization involves capturing knowledge through physical proximity. The

process of acquiring knowledge is largely supported through direct interaction with

people.

Externalization

Externalization requires the expression of tacit knowledge and its translation into

comprehensible forms that can be understood by others. In a way the individual

transcends the boundaries of the self. During the externalization stage of the knowledge-

creation process the individual commits to the group and thus becomes one with the

group. Knowledge gets crystallized through this process . The sum of the individuals'

intentions and ideas fuse and become integrated with the group's mental world. An

example would be quality circles formed in manufacturing sectors where workmen put

their learning and experience they have to improve or solve the process related problems.

30

In practice, externalization is supported by two key factors.

First, the articulation of tacit knowledgethat is, the conversion of tacit into

explicit knowledge involves techniques that help to express ones ideas or

images as words, concepts, figurative language (such as metaphors, analogies or

narratives) and visuals. Dialogues, "listening and contributing to the benefit of all

participants," strongly support externalization.

The second factor involves translating the tacit knowledge of people into readily

understandable forms. This may require deductive/inductive reasoning or creative

inference.

Combination

Combination involves the conversion of explicit knowledge into more complex sets of

explicit knowledge. In this stage, the key issues are communication and diffusion

processes and the systemization of knowledge.

The finance department collects all financial reports from each departments and

publishes a consolidated annual financial performance report. Creative use of database to

get business report, sorting, adding , categorizing are some examples of combination

process

In practice, the combination phase relies on three processes.

Capturing and integrating new explicit knowledge is essential. This might involve

collecting knowledge in the public domain from either inside or outside the

organisation and the combining such data.

Second, the dissemination of explicit knowledge is based on the process of

transferring this form of knowledge directly by using presentations or meeting.

Here new knowledge is spread among the organizational members.

Third, the editing or processing of explicit knowledge makes it more usable (e.g.

documents such as plans, report, market data).

The knowledge conversion involves the process of social processes to combine different

bodies of explicit knowledge held by individuals. The reconfiguring of existing

information through the sorting, adding, recategorizing and recontextualizing of explicit

knowledge can lead to new knowledge. This process of creating explicit knowledge from

explicit knowledge is referred to as combination.

31

Internalization

The internalization of newly created knowledge is the conversion of explicit knowledge

into the organization's tacit knowledge. This requires the individual to identify the

knowledge relevant for ones self within the organizational knowledge. That again

requires finding ones self in a larger entity. Learning by doing, training and exercises

allow the individual to access the knowledge realm of the group and the entire

organization.

In practice, internalization relies on two dimensions:

First, explicit knowledge has to be embodied in action and practice. Thus, the

process of internalizing explicit knowledge actualizes concepts or methods about

strategy, tactics, innovation or improvement. For example, training programs in

larger organizations help the trainees to understand the organization and

themselves in the whole.

Second, there is a process of embodying the explicit knowledge by using

simulations or experiments to trigger learning by doing processes. New concepts

or methods can thus be learned in virtual situation.

Back

32

Chapter 3

Strategic dimensions of KM; Impact of Business

Strategy

Introduction :

To understand strategic dimensions of KM, it is imperative to know the meaning and

implications of Business Strategy, its dimensions of KM & overall impact.

(A) Business Strategy:

In business parlance, Strategy implies differentiation.

In order to comprehend the overtone of this statement, the onus of any business is to

address 3 (three) issues:-

1. How any business creates value for money?

2. How does it make profit?

3. How the business differentiate from others?

The answer to these vital questions is to decide and devise the following:

Business Model identifies customers and describes how the business will profitably

address the customers needs and addresses to the first two questions.

Business Strategy is about differentiating how the business satisfies the customers and

is addressed to the third question.

Competitive strategy is about being different. It means deliberately choosing a different

set of activities to deliver a unique mix of value.

----- Michael Porter

Business Strategy is a plan to differentiate the enterprise and give it a competitive edge.

Definition:

Strategy is the patterns of decisions that shape the ventures internal resource

configuration and deployment and alignment with the environment.

33

Steps for Formulating Strategy:

1. Look outside to identify threats & Opportunity

At the highest level, strategy is to be devised to analyze outside environment. There are

threats new entrants, demographic changes, suppliers, product substitute etc.

2. Look inside at Resources, Capabilities,& Practices

A strategy can succeed only if it has the backing of right set of people and other

commensurate resources.

3. Consider strategies for addressing Threats & Opportunity

A) Create many alternatives

B) Check all facts and question all assumptions

C) Get the missing information

D) Vet the leading strategy with wisest men you know

4. Build a good Fit among Strategy- Supporting Activities

Strategy is not merely a blueprint for winning customers. It is about COMBINING

activities into a chain whose links are mutually supportive.

5. Create Alignment

Development of a strategy is half the work done. The other half is to create alignment

between people and activities.

Business Strategy, therefore, basically means differentiation with the competitors. This

differentiation can be any or all of these:-

a) Product / Services

b) Technology

c) Management style & practices ( HRD, Financial Management etc.)

d) Marketing

(B) Knowledge Management (KM):

To quote T S Eliot

Where is wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

Where is the life we have lost in living?

34

However, knowledge in KM does not necessarily mean the understanding of any

particular knowledge OR the depth of that knowledge - in any subject/topic/arena.

Knowledge in KM signifies any activity in the business which adds value to the

product/services.

To clarify it could be the methods / applications in any business primary/secondary or

even rudimentary whatsoever its degree may be.

Technology, or any aspect of value addition devices which may be any typically efficient,

Management system - adopted and practiced by the company could as well be the

distinguishing factors. These enable it to be different and hence makes it apart from its

competitors.

To illustrate from a common activity in any established business - the way how an

attendant serves tea / coffee to the employees / executives during tea/coffee break is also

a Knowledge. Because - in absence of that knowledgeable person, or in the eventuality of

a replacement serving tea/coffee from the same resources does not always meet the

requirement / expectation. The replacement, lacking the expertise, does not know the

choices/tastes of the beneficiaries. Consequently un-satisfactory serving may cause less

or no satisfaction thereby reducing the efficiency of the concerned employees

affecting their performances.

Knowledge is power.

We are living in a knowledge age. Present world economy is rightly termed as

Knowledge Economy. Knowledge is the edge by which a business organization can

sustain and thereby flourish.

India the new paradigm is rapidly ascending the knowledge chain. India is on the