Professional Documents

Culture Documents

GPR 410 Dissertation Ombaka 2012

Uploaded by

Kclf- Kenya Christian LawyersOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

GPR 410 Dissertation Ombaka 2012

Uploaded by

Kclf- Kenya Christian LawyersCopyright:

Available Formats

UNIVERISTY OF NAIROBI SCHOOL OF LAW

GPR 410: RESEARCH PAPER TWO DESSERTATION G34/2600/2008

6/12/2012

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

THE INSURANCE (MOTOR VEHICLE THIRD PARTY RISKS (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2010 : ITS EFFICACY IN REMEDYING THE STRUCTURAL PROBLEMS IN AWARD OF ACCIDENT COMPENSATION CLAIMS IN THE PUBLIC SERVICE VEHICLES (PSVS) UNDERWRITING INDUSTRY IN KENYA.

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF STATUTES ..................................................................................................................5 PARLIAMENTARY BILLS ..............................................................................................................5 TABLE OF CASES .........................................................................................................................5

CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY AND METHODOLOGY 1.1 BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................................7 1.2 STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM ........................................................................................9 1.3 RESEARCH QUESTIONS .................................................................................................... 10 1.4 HYPOTHESES ....................................................................................................................... 11 1.5 JUSTIFICATION .................................................................................................................... 11 1.6 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK ............................................................................................ 12 1.7 LITERATURE REVIEW ........................................................................................................ 15 1.8 METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................................. 18 1.9 CHAPTER BREAKDOWN .................................................................................................... 19

CHAPTER 2: ANALYSIS OF THE PROPOSED STRUCTURED LIABILITY SCHEDULE AND POSSIBLE IMPACT IN THE PSV UNDEWRITING SECTOR 2.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 20 2.2 THE PROPOSED STRUCTURED LIABILITY SCHEDULE ............................................. 21 2.3 THE HANCOX COMMISISON REPORT ............................................................................ 23 2.3 COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE BILL AND THE HANCOX COMMISSION RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................................... 30 2.4 CONCLUSION ....................................................................................................................... 32

CHAPTER 3: ANALYSIS OF COURTS CURRENT PRACTICE IN THE AWARD OF COMPENSATION 3.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 33 3.2 PRINCIPLES GOVERNING THIRD PARTY CLAIMS UNDER THE INSURANCE (MOTOR VEHICLES THIRD PARTY RISKS) ACT, CHAPTER 405 ....................................... 34 3.3 GENERAL PRINCIPLES GOVERNING AWARD OF COMPENSATION IN KENYAN COURTS ........................................................................................................................................ 36

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

3.4 CASE DIGEST ON CLAIMS MADE BY THIRD PARTY LITIGANTS AND AWARDS BY COURTS ........................................................................................................................................ 38 3.5 CONCLUSION ....................................................................................................................... 46 ........................................................................................................................................................... CHAPTER 4: CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 4.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 49 4.2 MERITS OF THE PROPOSED STRUCTURAL LIABILITY SCHEDULE AND RELEVANT AMENDMENTS....................................................................................................... 50 4.3 PITFALLS OF THE BILL: CONTEST OF INTERESTS ..................................................... 51 4.5 WAY FORWARD ................................................................................................................. 54 4.6 CONCLUSION ....................................................................................................................... 56 REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................. 57 APPENDIX I .57

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

TABLE OF STATUTES 1. The Insurance (Motor Vehicle Third Party Risks) Act Chapter 405 Of The Laws Of Kenya. 2. The Constitution of Kenya 2010. 3. Work Injury Benefits Act, 2007 (Act No. 13 of 2007). 4. TheLaw Reform Act Chapter 26 of the Laws of Kenya. 5. The Fatal Accidents Act, Chapter 32 of the Laws of Kenya.

PARLIAMENTARY BILLS 1. The Insurance (Motor Vehicle Third Party Risks(Amendment)Bill2010, Kenya Gazette Supplement No.37 (Bills No. 10) Of 2010 2. The Marriage Bill 2007

TABLE OF CASES 1. A.A.M v Justus Gisairo Ndarera & Another [2010]Eklr 2. Ajwang v The British India General Insurance Company Ltd [1967] E.A. 437- 443 3. Baker v Jason [1868] LR 3 CP. 4. Butt V Khan[1981] KLR 349 5. Daniel Lingete V Constatino Thomas H.C.C. 4084/83 6. Dr. Paul Macharia Ndirangu v V.K. Pattni & Another [2010] eKLR 7. Elock v Thomson [1949] 2 KB 755. 8. Eastern Bus Company v Bibi [1971] EA 370 at 373- 374 9. Feise v Aquillar [1811] Taunt 506. 10. 11. 12. Geraldine Tucker v Josephine Mary Leger HCCC No. 589 of 1971 Gianni De Caprio v Argo Films (EA) Ltd. and Another [1971]ea 438 Haigh v De La Cour [1812] 3 Camp 319.

5

(unreported) at 485

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

13. 14. eKLR 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 90 25. 26. 27. 28.

Hardy v Motor Insurers Bureau [1964] 2 All E.R. 746 Joash Nyabicha v Kenya Development Authority & 2 Others [2010] Joseph Otiende v Hayer Bistiany Nrb H.C.C. 972/92 Law Society of Kenya v Attorney-General [2008] eKLR Lewis v Rucker [1761] 2 Barr 1167. Llim Poo Choo v Camden and Islington Area Health Authority Mariga V Musila [1984] KLR 251 Mary Pamela Oyioma v Yess Holdings Limited [2011] eKLR Mondo v Jessa[1969] EA 156 Muko Tirikol Muiko Vs Attorney General H.C.C.C. 2045/96 Paul Kiviu Nzuma & Another v Jackson Mwilu [2006] Eklr Rahina Tayah & Another Vs. Anna Mary Kinaru [1987-88] 1KAR Steamship Balmoral v Maton [1902] AC 511 The New Great Insurance Company Of India Ltd. V Lillian Evelyn Wainaina v A.G. NRB H.C.C.C. 3473/91 Yorkshire Water v Sun Alliance and London Insurance [1917] 2

[1979] All ER 910

Cross and Another [1965] E.A 91 - 109

Lloyds Rep. 21.

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY AND METHODOLOGY

1.1 BACKGROUND PSV underwriting firms in Kenya are and have faced an increasing challenge with regard to solvency issues. Reports indicate that in the past decade over ten PSV underwriting firms have either been wound up or placed under statutory management.1A number of PSV underwriting firms have since closed shop, this list includes: the state-owned Kenya National Assurance Company Limited (1996), next was Access Insurance Company Limited, followed by Stallion Insurance Company Limited, Liberty Insurance Company Limited, Lakestar Insurance Company Limited, United Insurance Company Limited, Invesco Insurance Company Limited and Standard Assurance Kenya Limited followed in that order2. Media reports have indicated that at present one of the key players in the industry Blue Shield Insurance Company Limited. has been placed under statutory management. Blue Shield Insurance Company Ltd. is reported to have insured about fifty per cent of PSV motor vehicles and motor cycles by the time of its being taken over by the regulator3. Media reports also indicate that two other PSV major operators Direct Line Insurance Company Limited and Invesco Assurance Company Limited are in court seeking protection from settling claims worth 1 billion4.

allAfrica.com: Kenya: Crisis Looms in Plan to Deny Matatu Operators Insurance. *Online+. Available: http://allafrica.com/stories/201109220205.html. [Accessed: 11-Nov-2011]. ; allAfrica.com: Kenya: Regulator Takes Over Management of Blue Shield. *Online+. Available: http://allafrica.com/stories/201109190009.html. [Accessed: 11-Nov-2011].; The Standard Online | printer friendly version. *Online+. Available: http://www.standardmedia.co.ke/archives/print.php?id=1144016440&cid=159. [Accessed: 11-Nov-2011]. ; Reprieve for Blue shield PSV Policy Holders | Bizrika.com.*Online+. Available: http://www.bizrika.com/bankingand-finance/reprieve-for-blue-shield-psv-policy-holders.html. [Accessed: 08-Mar-2012]. 2 Ibid 3 Crisis Looms in Plan to Deny Matatu Operators Insurance Steve Mbogo, 22 September 2011 Nation Media 4 PSV underwriting now a mine field of fraud By Peter Thatiah , The East African Standard

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

One of the main issues cited in the media reports as contributing to the crisis in the sector is the lack of a systematic structure which courts can rely on when awarding claims5. It is stated in these reports that the lack of a structured system for award of compensations has led to discrepancies in the manner in which awards have been granted by the courts. This has led to a scenario where lawyers claim and are awarded huge amounts in compensation claims, that are sometimes fraudulently computed (Njenga 2011) . Insurance firms bear the brunt of settling such claims, and the weight is felt most by PSV underwriters due to multiple third party claims in accidents involving PSVs. The Industry players have thus been calling for the establishment of structured payments of claims system6. The government, through the office of the Deputy Prime Minister and the Ministry of Finance, has proposed an amendment bill7 that will introduce structured payment of claims. This amendment bill seeks to basically introduce a schedule for the structured payments of claims. In this schedule, the maximum awardable compensation claim is three million8- which is only awarded in the event of death. Injuries not resulting in death are awarded a compensation calculated as a percentage of the maximum award. A cause however related to the upsurge in claims is also the fact of the indiscipline witnessed in the PSV industry. This indiscipline has resulted into low or pathetic industry standards leading to numerous accidents. PSV operators are famed for punitive disregard of traffic rules. In 2004 the PSV sector was reported to have caused nineteen percent of the road accidents in the country (Chiteere and Kibua: 2004, quoting from Gachuki: 2004).This aspect, as a contribution to the bedeviling of the PSV insurance sector, may

5 6

allAfrica.com: Kenya: Crisis Looms in Plan to Deny Matatu Operators Insurance. supra supra 7 This amendment Bill seeks to amend sections 3 and 10 of the Insurance (Motor Vehicle Third Party Risks) Act Chapter 405 of the laws of Kenya. The Bill is titled The Insurance (Motor Vehicle Third Party Risks(Amendment)Bill, 2010 and was published as Kenya Gazette Supplement no.37 (Bills No. 10) of 2010 8 This maximum award is provided for under section 5 (b) of the Act. Chapter 405 supra.

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

however not be remedied by the insurance industry and is probably better handled by administrative law structures. The issue of This research therefore seeks to analyze the brunt of the proposed structured payments of claims on the PSV underwriting industry, whether it will contribute remedying the state of decline.

1.2 STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM PSV underwriting firms in Kenya have been facing grave structural challenges in their operation. At present there are only two PSV underwriting firms that are operating in the country. A number of PSV underwriting firms have in the recent past been unable to settle claims from third parties and as a result have been either been wound up or paled under statutory control. The voluminous claims are as a result of numerous accidents involving PSVs and high awards of claims by courts, which in some instances are made even to non existent claimants9, thus the issue of fraud. The lack of a structured system for the award of claims by the courts has allegedly exposed the PSV underwriting industry to fraudulent award of claims due to the unethical practices already stated. With the current challenges in the PSV underwriting industry, there is a risk that all the persons involved in the industry would have their interests prejudiced: whether it is loss of income from collapse in the industry which cannot operate in the absence of proper insurance institutions; or victims of accidents who will have to go uncompensated in the long term. The PSV sector is a key industry in the country. As of 2004 the sector offered direct employment to 80,000 persons and indirectly employed 80,000 more people. In the same year the industry paid 1.3 billion to the government in taxes. The people who use the PSV services range in the millions and are

9

Supra note 6

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

exposed to the risk of accidents thus the need for third party insurance, which can only be guaranteed if the PSV underwriting industry is robust. The immediate effect of this crisis is that there is bound to be loss of premiums when PSV underwriting firms are wound up. Investors in the transport sector are also bound to bear the weight of third parties who are injured while using their vehicles; such instances are already occurring10Investors will also be discouraged from investing in the PSV insurance industry and the PSV transport sector, impacting the countrys economy negatively. The proposed amendment to The Insurance (Motor Vehicle Third Party Risks) Act seeks to introduce structured compensation liability scheduleprobably in an attempt to curb the element of fraud and regularize the award of claims. This amendment may be a solution to the PSV underwriting firms problems. There is therefore a need that the practicality this amendment be analyzed in the light of the institutional capacity of the insurance industry and possible ramifications of the same.

1.3 RESEARCH QUESTIONS This research seeks to address the following questions: 1. Will the proposed structured payment of claims lead to better administration in the award of claims by the courts thus minimizing the claimed irregularity in the administration of insurance claims and fraud? 2. Will the structured payment of claims remedy the problem of unjustifiably exorbitant awards to accident victims? 3. Is there an adequate institutional structure in place to shoulder the proposed structured settlement scheme?

10

Supra

10

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

1.4 HYPOTHESES This research is based on the following assumptions: 1. That the amendment of The Insurance (Motor Vehicle Third Party Risks) Act Chapter 405 of the Laws of Kenya to introduce a structured compensation liability schedule will streamline the award of claims to third parties by the courts. 2. The streamlining of claims will minimize the element of exorbitant compensation awards and fraudin the making of claims by victims of accidents; PSV underwriting firms will thus only settle legitimate claims and thus avoid solvency crises.

1.5 JUSTIFICATION The justification for this study is primarily the fact that the PSV underwriting industry is facing an imminent collapse and there is thus a need for immediate strategies to remedy the sector. Fraud in relation to claims awarded by the courts has been cited as a major cause of the current crisis, PSV underwriters allegedly settling dishonest claims. The use of structured payments has been proposed as a remedy to the irregularity experienced in the award of claims. This proposal is contained in an amendmentbill that is in Parliament. This study would provide valuable insight on the need or otherwise for such an amendment as the Bill is being discussed in parliament,. Also, in the event that the Bill becomes law, a study of the efficacy of this proposal in remedying the crisis in the PSV underwriting industry would be essential in pointing out of such reforms would be of a great impact or conclusive ; or if there will be need for further extensive reforms. This study also does a comparative study of the administration of such structured compensation schemes in other jurisdictions. This analysis will

11

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

point out the structural capacity of the Kenya with regard to implementing proposals in the Bill.

1.6 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK This research is premised on two main broad concepts as follows: 1.6.1 Law and economics The theory of law and economics movement is also referred to as the economic analysis of law. The relevance of this theory to this research is the concept of law being used as a tool for facilitating wealth maximization. This theory is thus important in analyzing whether the proposed amendment would address the structural problems in the PSV underwriting industry. This theory is also relevant in considering probable responses of the Insurance and transport industry to certain factors when their economic interests with regard to these factors are affected by the enactment of laws. Richard Posner identifies the key tenet of this theory as the law being an instrument of wealth maximization. He describes a societys wealth as being the sum of all tangible and intangible goods and services weighted by prices of two sorts: offer prices i.e. what people are willing pay, and demand prices i.e. what price people demand to give up what they own. Hepoints out that the justice of economics is based on the idea of wealth maximization and holds that: a transaction or other change in the use of ownership of resources is good if it increases the wealth of the society. This theory is premised on the assumption that people are rationally maximizes their satisfaction even in making non-market decisions. Rules of law operate to impose prices on (or sometimes subsidize) these non-market activities thereby altering the amount or character of the activity. He thus concludes that common law rules are often best explained as efforts, whether or not conscious, to bring about either Pareto efficient outcomes.

12

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

Brian Bix (2006) describes Pareto transactions as those which leave two parties in contending sides both better off11. He points out thatnormally a problem arises since in most, if not all, transactions since one party has been left better off than the other party. To resolve this dispute a Kaldor - Hicks analysis is adopted12. The same is also referred to as a potential Pareto Superior. The gist of the Kaldor-Hicks analysis is that despite there being a loser in a transaction; the winner can opt to compensate the losses of the loser without prejudicing his position. Francesco Parisi (2000), incontributing to the law and economics school of thought points out that: The simple logic (behind the economic analysis of law) is that if humans are rational maximizers of their wealth or self interest in all their activities, they will respond to changes in exogenous constraints; such as laws and sanctions in a way that can be measured or predicted. He further posits that a change in legal rules, just like a change in relative prices, will affect human behavior; and that economic theory can assist judges and legislative bodies when facing difficulties in finding remedies for undesirable behavior. He again states that if people were to act rationally in maximizing non market contexts; rules of law can alter the amount or the character of non market activities by imposing a price on them. He also point out that this theory has been criticized with regard to its transactional competence i.e. it is not guaranteed that human beings are rational. This theory has also been criticized on the basis that maximization of wealth is dependent on its initial distribution. Finally this theory has been

11

The hypothetical circumstance relied on here-describing the Pareto principle- is one where two parties are contending over the entitlement to a given thing. The result of a determination on who deserves the entitlement will leave one party better than the other in a winner takes it all situations. This theory thus tries to posit a balance that may result in a possibility of a win-win situation. All parties are therefore satisfied. 12 Named after Nicholas Kaldor and JR Hicks, who came up with this proposition.

13

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

criticized due to its inapplicability with regards to inalienable rights, which preclude inhumane choices for instance the choice to commit suicide. 1.6.2 Economic analysis of accident law This theory more or less resonates with the economic analysis school of thought, though it is specific to accident law. Steven Shavell (1987) describes this concept as an analysis of the law determining compensation of accident victims using simple models to predict behavioral outcomes. He posits that the socially ideal solution with regard to accident insurance is that there be an optimal award for compensation that satisfies the need to award victim appropriately, and at the same time create appropriate incentives for injurers to reduce risk. This compromise is however hard to reach. On the issue of a no fault compensation system, he posits that if injurers are not liable for accident losses, they generally will not reduce risk appropriately. They may engage in risky activities to an excessive extent and will have no motive to take care. They will engage in risky activities provided they can derive any benefit. He further points out that where liability insurers cannot determine the injurers levels of care; injurers will prefer insurance policies that do not offer full cover since then they will have incentives to reduce the risk of liability. Thus there will be low premium rates, than if the rates were to be in place for full coverage. On the issue of negligence he submits that full cover of liability will negate the injurers requirement to take due care and will consequently in very high premiums, which is undesirable. This is where there is an uncertainty over the determination of negligence. He further sates that liability insurance would be desirable in the case of uncertainty of negligence. This is because the protection offered by liability insurance will not be so broad as to induce injurers to act negligently. Healso considers the operation of a pure accident insurance scheme. He posits that such a scheme would save on administrative

14

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

costs, as neither the insurers nor the victims would have to expend resources in trying to prove liability. He however cautions that such a scheme may have the effect of not providing injurers with incentives to avoid doing harm. Where the victims cannot influence the risk it becomes useful since the victims interest is most likely limited to the loss suffered and not the particulars of the damage. Hefurther posits that where the injurers are able to influence the risk; it is recommended that the victim receives a partial coverage in respect of the risk. This thus provides an incentive for the injurer to proactively avoid eminent risks.

1.7 LITERATURE REVIEW Onduso B. N. (2003)13 has written an assessment of the impact of the Insurance (Motor Vehicle Third Party Risks) Act Chapter 405 of the laws of Kenya on the insurance industry. She details the particulars of what constitutes liability and the contractual aspects of the compulsory motor insurance regime. She further details the interpretations given by the court on the contractual aspects of the third party compulsory motor insurance. She also details a comparative study of other regimes. The only subject that she touches on which relates to this research is a comment on the award of claims by the High Court. She points out, in passing, the unachievable desire by the Association of Kenyan Insurers (AKI) to have award of claims regulated by statute. She notes that it is impossible to conjure a law that can envisage all manner of injuries resulting from motor vehicle road accidents, but provision of general guidelines is tenable. Further,sherecommends that there should be established a no fault scheme. She further fronts for the provision of pauper briefs to help victims of accidents

13

University of Nairobi ,The motor insurance contract viz a viz the mandatory third party insurance Act |Cap 405 of the laws of Kenya. The impact of the provisions of the Act on the insurance industry . A dissertation handed in towards the partial fulfillment of an LL.B degree. (2003)

15

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

who cannot afford representation. She also fronts for sealing of loopholes, though no specific detail is provided, in the Insurance (Motor Vehicle Third Party Risks) Act. Herstudy is thus targeted at the compulsory third party motor vehicle insurance as whole and general recommendations for reform. She does not have a particular emphasis with regard to the PSV underwriting industry, which the focus of this study. Further the proposed structured settlement scheme is not the focus of her writings, probably because it had not come into existence at the time of her writing. Mwangi N. W. (2003)14 has written on the administration of compensation of victims of accidents under the Insurance (Motor Vehicle Third Party Risks) Act. The main focus of her study is to make a case for a no fault insurance scheme i.e. one in which compensation is not pegged on liability. She refers to a scheme based on the no fault principle as accident insurance, as opposed to liability insurance that has been established under the Insurance (Motor Vehicle Third Party Risks) Act. Shedoes not therefore concern herself with matters particular to the PSV underwriting industry with regard to the Insurance (Motor Vehicle Third Party Risks) Act this being the focus of this study. She also does not consider the proposed structured settlement scheme, since again it had no come into being at the time of her writing. Magambo J. Kirimi (1984)15 critiques the impact of the no liability without fault system which is the basis of the Insurance (Motor Vehicle Third Party Risks) Act. He further addresses the weaknesses witnessed in relation to this system. He opines that the fault principle should be dealt away with and that this regime should constrict itself solely to the compensation of victims of accidents.

14

University of Nairobi.The third party motor insurance, a case for reform. A dissertation handed in towards the fulfillment of an LL.B degree. (2003) 15 University of Nairobi.Compensation for Third party motor vehicle accident victims and the law .A dissertation handed in towards the partial fulfillment of an LL.B degree. (1984)

16

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

He states that the award of damages in the fault system is based on two major factors: the insistence that damages should not only be compensatory but also penal; and the issue of determining the damages for non pecuniary losses like pain and suffering. He further points out that there is no clear-cut way of measuring non-pecuniary losses. He says that even where a doctor is consulted he would only forecast the future in terms of probabilities and possibilities, and never in terms of certainty. Again, he terms the fault system as an expensive scheme since it heavily relies on investigation and involves intense litigations which introduce the encumbrance of hefty legal fees. He quotes Keeton and OConnel who opine that most of the money given in accident compensation ends up in the lawyers pockets and not the victims, thus that the fault regime is scheme that merely benefits the legal class. He points out that the law16 has set up liability insurance instead of accident insurance. This thus has the implication that the statute

17

contemplates only awarding compensation in cases which the injury

or death caused is as a result of negligent driving. He further claims, quoting from Kanywanyi, that the purpose of the fault principle was part of a capitalist mechanization to keep motor insurance fund at a minimum and therefore maximize profits. In conclusion, he proposes that the compensation of accident victims be handles by a social security scheme managed by the state. This scheme is to be financed by government taxes and contribution from main stakeholders. This scheme should be based on a no fault principle and should thus have as its primary concern the creation of a security achieving protection for individual persons against injury or death from road accidents. The implication of this proposal is the doing away with of commercial companies offering compulsory third party motor insurance. He does no thus concentrate on PSV

16 17

The Insurance (Motor Vehicle Third Party Risks) Act supra

17

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

underwriting firms in particular but analyzes the regime as a whole as covered under the Insurance (Motor Vehicle Third Party Risks) Act. This research is however constrained to PSV underwriting. He also does not cover issues regarding the proposed structured settlement scheme, which had again not come into being at the time of his writing.

1.8 METHODOLOGY This research employed both primary and secondary means of data collection. The primary data collection methods involved interviewing various persons. The key persons who should have been interviewed included personnel at the Insurance Regulatory Authority who are technical experts with regard to claims and insurance premiums. Such person(s) would be instrumental in providing information on the impact of the proposed amendment on the PSV underwriting industry. Another category earmarked for interviews were persons working at PSV underwriting firms. These interviews would provide crucial information regarding the challenge of having unstructured payments; whether or not they supported the proposed amendments; and their expectations from the same. Interviewing lawyers engaged in the relevant kind of litigation would also be useful. However these interviews were not carried out as proposed due to time constraints. All the same some of the secondary materials had the necessary information thus primary data was expendable. The secondary data collection methods employed included: studying of relevant reports, obtaining statistics on PSV underwriting firms, internet research on relevant scholarly sources on this subject area, studying case law and statutes as well as other academic materials that were relevant to this subject.

18

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

1.9 CHAPTER BREAKDOWN The chapters in this study are as follows. The first chapter is the background to the study and methodology.This chapter contains the introduction and background to the study. This chapter outlines the research methodology and the considerations that were taken into account in the study. The third chapter is the analysis of courts practice in the award of compensation. This chapter is a comparative detail of court awards of compensation. The purpose is to point out or determine the extent to which discrepancies, if any, lie in the award of compensation. This chapter thus details a summary of select cases involving motor vehicle third party compensation. The second chapter is the analysis of the proposed structured liability schedule and impact in the PSV Insurance sector. This chapter detailsthe actual structural adjustments that are proposed by the structured compensation liability schedule.In this chapter the probable legal implications of the amendments are analyzed, and a comparative study with other jurisdictions outlined. Finally, the probable effect of the amendment with regard to the structural problems in the PSV underwriting industry is analyzed. The final chapter is the conclusions and recommendations chapter.This chapter will contain the conclusions drawn from the research and the appropriate recommendations.

19

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

CHAPTER 2: ANALYSIS OF THE PROPOSED STRUCTURED LIABILITY SCHEDULE AND POSSIBLE IMPACT IN THE PSV UNDEWRITING SECTOR

2.1 INTRODUCTION A bill seeking to introduce a structured liability schedule has been introduced in parliament by the Minister of Finance. This introduction of such a schedule would lead to insurers liability being limited to an amount prescribed by the schedule in accordance with the injury incurred by the victim, once liability is proven. This schedule does away with the non pecuniary damages with regard to compensation claimable from an insurer. This may mean that the victim of an accident would be forced to pursue the owner of the vehicle for a settlement of the balance not claimable from the insurer. This can be argued to be having a positive effect on the PSV underwriting sector as it will lead to insurers settling claims for bodily injuries only. In fact when the bill was tabled in parliament a major insurance company in the company expressed interest in the PSV underwriting industry of which it does not participate in at present but later dragged its feet probably due to the alleged challenges facing the passing of the bill in parliament (Njenga 2011). The genesis of the proposed structured liability schedule, in opinion, may be linked the recommendations in the Commission on the Insurance Industry and the Limitation of Compensation for Personal Injury Chaired by Mr. Justice A. R. W. Hancox also known as the Hancox Commission Report in 1987. The memorandum to the bill has no mention to this regard; however a similar recommendation was made in the report as well as others. However, in my consideration, the Hancox Commission report is so far the document with the most detailed analysis of the status of the motor vehicle accidents compensation regime and one of the public documents that in which a

20

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

structured liability schedule for third party motor vehicle insurance is mentioned. It would therefore be prudent to compare the proposed structured liability schedule in light of the proposals of this report, which justifiably acts as a benchmark. If the structured liability schedule is perceived not be satisfying the needs of all the stakeholders especially victims of motor vehicle accidents then there is a likelihood that it would not pass in parliament and even if it does it may be challenged in court. An analysis of the bill, especially in light of the recommendations of the Hancox Commission would reveal whether the proposed amendments include the necessary systems for the operation of such a schedule. If the amendment is not well structured its operation would be hampered and it would thus be of no effect and may be challenged as unconstitutional since it would seek to oust the jurisdiction of the courts18 . Therefore even if the amendments seem favorable to the PSV underwriting sector, they would not remedy the structural problems since they would be operational.

2.2 THE PROPOSED STRUCTURED LIABILITY SCHEDULE The Bill basically introduces a structured compensation liability schedule which would guide the manner in which compensation is administered. The maximum compensation awardable is Kshs. 3,000,000 in accordance with section 5 (4) of the Act. The gist of the schedule is that the award of compensation claims arising from victims of motor vehicle accidents will be determined according to the schedule upon proof of liability. This schedule is prescribed by the Minister of Finance in consultation with the director of medical services, who would also prescribes the amount claimable for a category not included in the schedule. In the application of the schedule therefore, the court will determine the amount payable as damages to the injured victim, then the amount payable by the insurer will be determined as

18

A similar claim was brought by the Law Society of Kenya regarding the Work Injury Benefits Act, 2007 in the case of Law Society of Kenya v Attorney-General [2008] eKLR.

21

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

per the schedule. The probable effect therefore would be that the injured person would be allowed to pursue the owner of the vehicle for any balance above the amount compensated by the insurer in a case where the liability schedule prescribed a figure lower than the actual damages awarded. Operation of the liability schedule The schedule has three main categories for compensation which are: death, which attracts maximum compensation at Kshs. 3,000,000; blindness which attracts a graduated liability up to the maximum amount; and a category for general damages which entails various injuries for various body parts awarded at various scales being a fraction of the maximum amount. The schedule contains a list of 39 injuries graduated at different scales and defined in different circumstances. As already stated, any injury not in schedule is to be referred to the director of medical services for a determination of the scale under which it would fall. Therefore if for instance if a victim of an accident ends up with total blindness as a result of injuries arising from the accident, such a person may be awarded a claim of 100% of the total claimable amount which is Kshs. 3,000,000 by the insurer of the person who is liable. However if the blindness is partial then he may be entitled to receive an award of up to 75% which is Kshs. 2,225,000. Therefore even if the injury incurred would attract damages amounting to Kshs. 4,000,000 for instance, the insurer will only be liable to pay the victim up to the amount prescribed by the liability schedule. In another instance a unilateral injury of the shoulder luxation attracts a claim of up to 5% of the maximum awardable amount from the insurer while the loss of a finger attracts an amount of up to 2% of the maximum amount regardless of the amount awarded as damages by the court. There is no mention of non pecuniary damages, probably this would mean that the percentage to be awarded is either assumed to have an account of the possible non pecuniary damages, which is my opinion impossible, or that the issue of non pecuniary damages has been done away with altogether. It is in

22

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

my opinion impossible to include non pecuniary damages in affixed schedule since by their varied nature they can under be administered under a judges discretion e.g non pecuniary damages sought by a doctor would not be equivalent to those sought by a cobbler.

2.3 THE HANCOX COMMISISON REPORT This commission was set up due to the rising cost of insurance premiums as a result of the numerous compensation claims especially with regard to the introduction of matatus in the PSV sector. This commission made inquiries among various stakeholders in the motor vehicle accidents compensation regime. These stakeholders included PSV operators organization, The Public Law Institute, the Law Society of Kenya, the Association of Kenya Insurers, technical and legal experts in the regime amongst others. The main recommendations in this report, which were that Kenya should adopt a two tier system with a no fault liability system up to a given value of claims and subsequent court adjudication for higher claims never, saw the light of day (Njenga 2011). In my opinion, a structured liability schedule was part of the recommendations in the report and not the main recommendation. The Hancox commission report recommended a system that would take care of the interests of all the stakeholders in the motor vehicle accident compensation regime. I would equate the proposed structured liability schedule to a mere pull out from the many recommendations of the commission and thus falls short of the industry standards. The structured liability schedule is however a favored by most insurance industry players both those in the PSV underwriting and otherwise since it is perceived to have been crafted in their favor (Njenga 2011). The bill may thus be argued to possibly be able to remedy the structural problems faced by the PSV underwriting industry. The big question is whether it will be allowed to operate while being short of the systemic standards proposed in the Hancox Commission report, thus possibly occasioning injustice to victims of motor vehicle accidents seeking compensation.

23

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

Background to the Hancox Commission The background to the instituting of this commission was that the third party liability compensation regime19had been working well since its inception in 1946 when the Act came into operation. By the time of the Acts inception public transport was comprised of trains operated by the East African Railways and omnibuses operated by the Kenya Bus Service. Claims arising out motor vehicle accidents were manageable as the persons involved were few, probably due to the low population and minimal participation of Africans in the colonial economic space. The report points out that problems with regard to compensation of accident victims rose when the matatus were accepted as a mode of public transport. The Hancox Report cites a MAZINGIRA Report which states that matatus became formally recognized in the PSV sector after a declaration by the then President Kenyatta. Kenyatta only required the matatus, which at that time operating under no regulation and harassment from the police, to comply with the existing traffic laws. In the Hancox Report it was pointed out the matatus were a response to a transport crisis in the country. Since independence more people were involved in economic activities coupled with growth in population, thus an increase in the numbers involved in motor vehicle accident compensation. The introduction of the matatus for instance meant that the numbers for persons from a single accident would be a big figure. There was also an alarming trend pointed in the award of claims in court which was first irregular, and secondly ever increasing. The trend in the motor vehicle accident compensation regime was noted to have stemmed from the compensation as of right concept espoused by the Act20. There was thus need for reforms to be adopted since there was a looming crisis with PSV underwriters back then facing the challenge of collapse and victims of motor vehicle accidents facing the risk of not being compensated the circumstances

19 20

Established under the Motor Vehicle (Third Party Risks) Insurance Act Chapter 405 of the laws of Kenya supra

24

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

in the PSV underwriting industry, as demonstrated in the first chapter of this dissertation, have remained the same if not worse. Analysis of court awards and proposals in the report There was an alarming disparity in court awards of compensation involving motor vehicle accident victims. . A number of court awards compensation of motor vehicle accident victims from various High Courts in the country were cited in the report. These were from judgments delivered in the period of 1983 to 1985. In variation was as a result of the practice of the independence of the judiciary which, as stated in the report, Kenya was proud of. The other reason pointed out in the report as possibly contributing to the variation in court awards was the fact that damages awarded for non pecuniary losses like pain and suffering and loss of amenities of life are discretionary. The proposals settled on for deliberation was whether to adopt a pure no fault system, or a two tier no fault system with the option of court adjudication for compensation awards beyond a certain limit. A Mr. Gitao, who was at the time a reputed lawyer in this area representing about 10% of the insurance firms at the time, was opposed to a pure no fault system, but welcomed the idea of a compensation ceiling being in place in order to make the compensation system economically viable. He proposed that if a structured liability scheme was to be instituted, then all the heads that are presently considered in the determination of compensation awards should be included. A Mr. Sampson, who was at the time a commissioner of Assize21, favored a structured compensation scheme similar to the one contained in the Bill. A Mr. Robert Gumba, who was at the time the deputy chairperson of the Law Society of Kenya Western Kenya, opined that the taking away of power from the courts had always ended up in degeneration and thus such systems were ultimately challenged in court. His statement brought out the sense that court

21

He was also reputed in the report as having unmatched expertise in the area of motor vehicle accident compensation

25

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

determination of accident compensation awards had a sense of legitimacy despite the fact that they may end up being exorbitant. A Mr. Noad, who was at the time an experienced legal practitioner in this field, stated that, the no fault scheme was aa wholesale amputation of powers from the courts. He was thus opposed to it but favored the placing of a limit on the amount of compensation payable. The main contention therefore noted in the proposals given to the commission was whether the courts should be allowed to continue administering compensation for motor vehicle accident victims and that they be replaced with a no fault system; or if the courts were still to be left to administer the regime, the appropriate safeguards to be adopted. One of the issues raised with the no fault regime was that it may prove to be inadequate in the face of persons with serious injuries, though the same was stated as one of the disadvantages of the fault system. There was a clear indication from the lawyers who made presentations before the commission that a system that intended to take away the motor vehicle accident compensation regime from the courts was not desired. Comparative analysis of no fault systems A number of persons who appeared before the commission were in favor of a no fault system. A Mr. Adam Ali was the most vocal in championing for a no fault system. He opined that the current fault system did not guarantee premium stability and should thus be avoided. In his opinion, the advantages of a no fault system were that: insurance companies would be enabled to reduce high premiums while maintaining viability of the industry; high legal associated with the tort fault system costs were eliminated; settlement of claims was expeditious with time spent before compensation being awarded being at a minimum; and compensation will be paid to all injured persons regardless of who is at fault. The tort fault system was criticized as having disadvantages such as:

26

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

a) It was said to be an incomplete system in that persons with lesser injuries were overcompensated yet persons with major injuries were undercompensated; b) The fault system was said to be very slow in administering compensation, as court determination of fault and settlement could even take years before being finalized; c) The fault system was deemed to be inefficient due to high service costs, especially legal related costs. Mr. Ali estimated that about 50% of the amounts awarded went to legal costs, while Mr. Gitao estimated that the figure for legal service costs were about 30% to 40%. The commission thus had the opportunity to do a comparative study of the no fault systems in various jurisdictions including: India, New Zeland, the Michigan State of the United states of America, and the eastern province of Quebec in Canada. I have given details of a few of these suggested systems as contained in the report, which I deem relevant to the subject of this paper. The Indian no fault system was fronted for by Mr. Ali. It was described as a two tier no faulty system. In the first tier claims were awarded in lump sum regardless of fault for any injury up to a given value. In case of any claim of injustice by the victim, thus the need to seek a greater claim, appeals could be made by such persons to a tribunal set up for adjudicating such claims. The tribunals was composed of persons who were former judges or had worked in the justice system, this was so as to preserve the judicial nature of the tribunal. The award of compensation is administered by a government accident injury claims office. The purpose of the two tier system was to withdraw the motor vehicle accident regime from the mainstream court jurisdiction, but at the same time maintain the court standards in the administration of such claims. The Public Law Institute represented by Dr. Ombaka and Mr. Bitonye (as they were then) however pointed out that the two tier system in India was being plagued by a phenomenon of double compensation. This was a case where victims would

27

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

claim under the first tier and then use the amount awarded to claim under the second tier. This aspect was stated to have the effect of defeating the philosophical and jurisprudential foundations of the no fault regime. The system in New Zealand was quite comprehensive, and covered injuries in a wide range of accidents and not only victims involved in motor vehicle accidents. Compensation under this system is up to a given maximum and is determined according to a persons income. Compensation for persons deceased as a result of accidents is made including an amount to cover funeral expenses. Compensation of victims is handled by the Accident Compensation Corporation which is a body corporate. The compensation system was by then being funded by levies on employers, motor vehicles and motor vehicle drivers. The Public Law Institute however submitted that the system in New Zealand was facing financial challenges especially in relation to sectors such as sports in which the revenues collected did not match the amounts awarded from the compensation of injured persons. The Quebec system was stated to be the most stable compared to the others systems then. This system was noted as not having faced any problems by then despite having awarded a number of compensation claims. Quebec was stated as being the largest easternmost province of Canada. Victims of motor vehicle accidents were entitled to compensation from the Regie De LAssurance Automobile Du Quebec as prescribed under their relevant Act, which was an equivalent of the corporation in New Zealand. Under the Quebec system, all the rights for instituting court action for motor vehicle accident related injuries are abolished. The principles observed under the Quebec compensation scheme include: a) Universality of compensation, that all Quebecers are entitled to compensation for motor vehicle related accidents regardless of whether the accident occurred within the province or not. b) Compensation is awarded regardless of fault, even if the fault lies with the victim;

28

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

c) Compensations include pecuniary losses and non pecuniary losses such as income lost as a result of the injuries, as well as compensation where the injured person dies; d) Compensation is determined according to the price consumer index22, in order to ensure the appropriateness of the award; e) The compensation scheme is funded by incomes arising from motor vehicle levies. Recommendations of the commission The options tabled before the commission were: to propose a pure no fault system like the one in New Zealand and Quebec; propose a two tier system like the one in India; or maintain the system as was then, which is predominantly how the system still is. Having a ceiling for the maximum compensation awardable under the act was recommended. This recommendation was applied under an amendment to section 5 of the act which limited the maximum amount that can be compensated under the Act at Kshs. 3,000,000. Justice Hancox pointed out that the tort fault system could not be regarded as a total failure, as opined by Mr. Ali, since it had worked well prior to the surge in numbers in the transport sector. This statement is however disputable considering the number of progressive jurisdictions that have abandoned the fault system and adopted the no fault system. A better position would probably be to state that the torts fault system, though it had been previously efficient when numbers involved in transport were relatively small, faces grave challenges in the onset of a growing transport sector.

22

Consumer Price Index is defined as a measure of the weighted aggregate change in retail prices paid by consumers for a given basket of goods and services. Price changes are measured by re-pricing the same basket of goods and services at regular intervals, and comparing aggregate costs with the costs of the same basket in a selected base period Price data for constructing the indices are collected by Kenya National Bureau of Statistics through a survey of retail prices for consumption goods and services. The percentage change of the CPI over a oneyear period is what is usually referred to as inflation. Source : http://www.knbs.or.ke/consumerpriceindex.php

29

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

The commission proposed the adoption of a two tier system akin to the one in India working within the system of the privately owned motor vehicle insurance regime. This would be a system in which compensation is guaranteed up to a given limit under the first compensation tier. The second tire would involve persons who deem compensation under the first tier as being inadequate and therefore wanting to seek a court determination so as to be granted further compensation. The commission however noted that such a system should be adapted to the Kenyan circumstances. It was stated that a wholesome importation of the Indian system into Kenya would be disastrous since in Kenya the Insurance industry is private as opposed to the one in India relating to the compensation of motor vehicle accident injuries that is publicly controlled. There was also need to put in place safeguard systems that would guard against double compensation as was allegedly happening in India. Such safeguards would include limiting the right of accessing the second tier to very serious cases. Another safeguard proposed was that of claims awarded under the first tier being considered when awarding claims under the second tier. Compensation was also to be under a structured compensation liability schedule. Other ancillary recommendation related to putting in place stringent motor vehicle inspection regulations and the requirements of safety belts and installation of speed governors for PSVs. The latter recommendations were for a while enforced under the Michuki Rules mention in the first chapter but later collapsed due to administrative incompetence in the traffic law enforcement mechanism.

2.3 COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE BILL AND THE HANCOX COMMISSION RECOMMENDATIONS I do not think that a conclusion that the structured liability schedule is a concept borrowed from the recommendations of the Hancox Commission Report. Therefore an analysis of whether the amendment meets the structural requirements outlined in the Hancox Commission report. My conclusion is that

30

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

the bill falls short of the structural and systemic requirements proposed in the Hancox report and amounts to a proposal favoring only one of the many stake holders the insurance underwriters. Though the proposals may in theory be deemed to solve the structural problems in the PSV underwriting industry since it would limit the amounts claimable from insurers, the operation of the schedule would be challenged by other stakeholders who would be disadvantaged i.e. PSV operators, victims of accidents and probably lawyers who according to a lawyer in Njengas book (2011) would be facing the risk of being flushed out of the regime. First, the bill makes no mention of the institution that will be in charge of determining the level of injuries in accordance with the schedule. There is even no mention of such powers to determine the body responsible for administration of the schedule being given to the minister. This is bound to bring about confusion. Secondly the fact that non pecuniary damages which form the bulk of damages awarded are not awardable would mean that PSV operators are left with the burden of bearing the non pecuniary damages and thus the PSV underwriting sector may be bound to lose since the PSV who are supposed to pay premiums to support the industry will be engaged in settling court claims. The problem would thus have been shifted to another player in the industry but still in within the same industry. That is probably why the Hancox Commission Report recommended a two tier system, taking into cognizance the fact that a single tier would occasion injustices. Thirdly, the amendment will face stiff opposition within parliament, or without because it will be perceived to be acting to disadvantage victims of motor vehicle accidents and may be bound to face court challenges especially in this current era of liberal constitution that grants courts the power to develop rights23 and thus such an amendment would have a high likelihood of attracting judicial activism.

23

Article 20 of the Constitution of Kenya 2010

31

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

2.4 CONCLUSION The proposed structured compensation liability schedule is prima facie a solution to the problems in the PSV underwriting industry since it would lead to payment of lesser claims by the insurers. However the bill falls short of the recommendation in the Hancox Commission Report and therefore works to the disadvantage of various stakeholders and more so the victims of motor vehicle accidents. The proposed structure therefore falls short of appreciating the various interests that have led to the present structural crisis in the PSV underwriting sector and may thus be bound to face a stiff challenge whether in parliament or outside. The current constitutional dispensation also opens doors for judicial activism and such an amendment that may be viewed to working to disadvantage of motor vehicle accident victims would be a definite target. The structured compensation liability schedule as proposed in the bill also lacks certain basic structural and systemic components and would thus be bound to bring confusion in its application and be challenged by lawyers as was the Work Injury Benefits Act, 2007 (Act No. 13 of 2007). The application of the amendments may thus be rendered inoperative by the various stakeholders who will be disadvantaged, thus its benefits to the PSV underwriting sector will not be taken advantage of.

32

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

CHAPTER 3: ANALYSIS OF COURTS CURRENT PRACTICE IN THE AWARD OF COMPENSATION

3.1 INTRODUCTION This chapter details a comparative analysis of court awards of compensation with regard to third party motor insurance. The purpose would be to point out or determine the extent to which discrepancies, if any, lie in the award of compensation. This chapter also analyzes the amounts claimed by litigants in these cases and how that impacts This chapter will thus detail a summary of select cases involving motor vehicle third party compensation. A person seeking compensation in a motor vehicle accident case is supposed to issue notice to the defendants insurer within fourteen days of instituting the proceedings against the insured defendant24The insurer thus awaits the outcome of the suit brought against the insured and settles the claim if the plaintiff succeeds. The law stipulates that the insurer is supposed to settle the claim, including any costs incidental to the suit, even when entitled to avoid the policy25. Compensation claims for fatal accidents are brought under the Law Reform Act and the Fatal Accidents Act upon proof of the defendants negligence. Njenga (2011)26 argues that the entry of lawyers into the PSV insurance sector was the beginning of all the problems that now face the PSV underwriting industry. He claims that it is lawyers who are responsible for the award of inflated compensation to motor vehicle accident victims, and that the PSV underwriting industry has become the lawyers source of bread and butter. The damaging effect on the insurance industry of awarding exorbitant compensation claims for accident victim was noted by Hancox J in Mariga V

24 25

Section 10 (2) The Insurance (Motor Vehicles Third Party Risks) Act, Chapter 405 Section 10(1) Supra 26 Njega G. (2011) Thriving On Borrowed Time. Hope Centre International. Nairobi

33

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

Musila27 where he cautioned that an unduly emotive stance should be avoided with regard to compensation. He went on to say that if [the damages awarded] get too large then we are in danger of injuring the body politic as large sums are awarded so premiums for insurance rise higher and higher28. A look into the practice in award of compensation claims by courts resulting from motor vehicle accidents would thus be important to this study, especially in determining any existing irregularities thus substantiating the need for a review of established practice.

3.2 PRINCIPLES GOVERNING THIRD PARTY CLAIMS UNDER THE INSURANCE (MOTOR VEHICLES THIRD PARTY RISKS) ACT, CHAPTER 405 The purpose of the legislature in enacting the Insurance (Motor Vehicles Third Party Risks) Act, Chapter 405 was described by Crabbe J.A. In the land mark29 case of TheNew Great Insurance Company Of India Ltd. V Lillian EvelynCross and Another30as being, to ensure that any damages that are recovered by an injured third party will be paid by an insurance company. Newbold V-P, in the above mentioned case, gave a ruling to the effect that by virtue of section 8 of the act31the insurer had a statutory duty imposed upon him to settle any liabilities that would arise upon the insured owner of a vehicle with respect to third parties. He retreated that the third party cover must be against any liability which may be incurred, and that the cover is on the vehicle whether being used by the owner who took out the policy or not. Crabbe J.A. went on to state that all that an injured third party had to prove was that the injury had been caused by use of the car on the road; that

27 28

[1984] KLR 251 Mariga vs. Musila[1984] KLR 251(1982-88) 1 KAR 507 29 Newbold, VP his ruling commented that this case was of considerable importance to insurance companies and the general public. Sir Clemens De Lestang J.A also stated that this was the first time that such a matter, which primarily dealt with whether an insurer can avoid a third party policy by means of exclusion terms in the policy of insurance, was appearing before the court. 30 [1965] E.A 91 - 109 31 Supra

34

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

judgment had been obtained against the owner of the vehicle; and that a valid policy in accordance with the act was in force at the material time. Only Sir Clement De Lestang dissented in his judgment. He argued that if the rules of construction were to be relied upon, only the conditions stipulated in section 16 of the act

32

bar the insurer from excluding liability33

thus the insurers

exclusion in this case was not valid. The ruling in The New Great Insurance Company of India case in effect gave a blank check to an injured third party in motor vehicle accident to recover from the insurance company, regardless of the terms of the policy or conduct of the insured. Crabbe J.A went on to quote Lord Denning M. R34 who stated that, [the policy] must be wide enough to cover, in general terms, any use by [the insured owner] of the vehicle, be it an innocent use or a criminal use of the vehicle, a position that was shared by Pearson L.J in the same case. Pearson L.J. held that section 10 of the Act35 granted an injured third party a right to be compensated by the insurer. In essence therefore, once the liability of an owner of a vehicle has been proved, and there exists a valid policy the insurer is bound to settle the claim. This position was followed by Phadke Ag. J in the case of Ajwang v The British India General Insurance Company Ltd36. In this case the defendants sought to avoid the policy arguing that the vehicle, at the time of the accident, was not being used for the purposes for which it had been insured. The insurance policy read that the car was to be used for social and domestic

32 33

Supra Section 16 enumerates matters which if relied upon in a third policy by an insurer to exclude liability would be of no effect. Sir Clements argument was that section 16 has the effect of limiting section 8 which is construed broadly. He argued that the rule of construction was that where two provisions in the same act are repugnant the latter prevails. In this case the exclusion being relied on by the insurers to avoid liability was not included in section 16, sir Clement thus held that the exclusion was valid. Newbold however stated that the rules of construction were merely a means to an end and thus chose not to be bound by them. He also pointed out that the circumstances in East Africa favored a permissive interpretation of section 8 of the Act. 34 Hardy v Motor Insurers Bureau [1964] 2 All E.R. 746 35 Supra 36 [1967] E.A. 437- 443

35

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

pleasure purpose but was at the time of the accident being used for ferrying fare paying passengers. The insurance policy thus sought to claim that there was no valid policy in force as a result of the vehicles use contrary to the insurance policy. Phadke Ag. ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, holding that section 10 grants right of compensation to an injured third party, and liability can therefore not be avoided by virtue of an insured breaching the terms of the policy.

3.3 GENERAL PRINCIPLES GOVERNING AWARD OF COMPENSATION IN KENYAN COURTS The Kenyan system of compensation for injuries arising from motor vehicle accidents is governed by the principles of damages in tort law. In particular the principle of compensation expressed in Latin as restitution in integrumis relied upon in assessing the quantum of damages (Kuloba 2006)37. The principle of compensation denotes that that which is lost as a result of an actionable harm should be compensated in as far as monetary terms can suffice, and this compensation should be adequate (supra). Damages awarded in accident claims normally fall under two heads: special damages and general damages (supra). Special damages are damages that are alleged to have been sustained in the circumstances of a particular wrong, and must be specifically claimed and proved38. Genera damages are those damages that the law presumes follow from the type of wrong incurred39. General damages are both pecuniary and non-pecuniary. Pecuniary losses are those that can be quantified in monetary terms. Items that would fall under this category include: future losses such as lost income due to incapacitation and consequential losses such as loss of learning capacity and lost opportunities to earn an income (Kuloba, supra). Non pecuniary losses would include items such as pain and suffering. In most

37

Kuloba R. (2006) Measure Of Damages For Bodily Injuries. Law Africa. Nairobi Blacks Law Dictionary(2004), 8 Edition. Thomson West. Texas. Supra.

th

38 39

36

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

cases general damages are the subject of contention since first they are largely discretionary and in most cases no concrete evidence40 is presented to the court but rather claims are made with a view of swaying the courts mind in the litigants favor. Claims for persons who die as a result of motor vehicle accidents are brought under the Fatal Accidents Act41 and the Law Reform Act42. The once and for all rule is also applied with regard to the assessment of damages. A litigant must therefore sue for all damages- past, present and future- since once a determination is made the court cannot make a subsequent determination to review the award for compensation based on the same fact (supra). A litigant cannot for instance maintain an action for a broken arm and subsequently for a fractured rib, though he was unaware at the commencement of the first action43. The fact of damages being discretionary coupled with the need to cover all damages past, present and future has probably led to what I would term a casino like approach being adopted by litigants seeking compensation, especially in motor vehicle insurance third party claims. Litigants seek to place the highest bet and the court is left to tone down high awards44. A look through a number of cases brought before Kenyan courts shows that most litigants, through their lawyers, seek any imaginative avenue to get the most from the insurer. This approach could be predicated on the fact that the claims made against the owner of a vehicle who is found liable will be settled by an insurance company as already noted above. This therefore leaves an avenue for the possibility of collusion between lawyers and doctors to come up with fraudulent claims. So far, the

40

See for instance the Case of Eastern Province v Bibi [1971] EA 370 at 373- 374, where the Lutta J.A. noted that the evidence concerning pain and suffering was scanty and there was no evidence of his family background. 41 Chapter 32 of the Laws of Kenya 42 Chapter 26 of the Laws of Kenya 43 Wicks J (as he then was)in Gianni De Caprio v Argo Films (EA) Ltd. and Another [1971]ea 438 at 485 44 More on this aspect is covered in the case digest later on in this chapter.

37

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

highest awards for compensation are given in cases where the victim suffers paralysis as a result of the accident45. In practice, as noted by Lutta J.A. in Eastern Bus Company v Bibi46, appellate courts are reluctant to interfere with the exercise of the discretion of a trial court in regard of an award of damages unless [the appellate court] is satisfied that the reward is wrong or is predicated on wrong principles. Hancox J.A in Mariga v Musila47 also repatriated this position that appellate courts are entitled to disturb an award of damages only if it is as high or low as to represent an entirely erroneous estimate. It must be shown that the judge proceeded on wrong principles, or that he misapprehended the evidence in some material respect and so arrived at a figure which was either inordinately high or low48. It is therefore rare for an appellate court to radically reduce the amount of damages awarded, and of course such reduction of awards may possibly prejudice litigants rights. The fact of the award of damages being discretionary also means that the court relies heavily on precedents, so any increase in damages awarded in any case sets pace in raising the bar for claims.

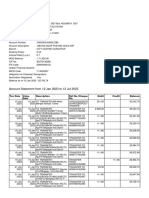

3.4 CASE DIGEST ON CLAIMS MADE BY THIRD PARTY LITIGANTS AND AWARDS BY COURTS The cases analyzed below are sampled from various High Courts across the country. In all these cases, the assessment of the quantum of damages was an issue. All the cases arise from motor vehicle accidents causes, though not particularly ones involving PSVs. There is a lot of reference to Kenyan case law in these cases, thus I am convinced that this case digest is genuinely representative of courts practice in the award of damages.

45

Llim Poo Choo v Camden and Islington Area Health Authority [1979] All ER 910; Geraldine Tucker v Josephine Mary Leger HCCC No. 589 of 1971 (unreported);Mondo v Jessa[1969] EA 156 46 Supra at pp 372 47 Supra 48 Quoting from Law J.A. in Butt V Khan[1981] KLR 349

38

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

3.4.1A.A.M V JUSTUS GISAIRO NDARERA & ANOTHER [2010]EKLR This case the first defendant who was the driver of a van knocked down the plaintiff who was walking beside the highway. This case was heard by J.M. Khamoni at the High Court in Nairobi over a period of seven years. The first defendant was in the course of his employment thus making the second defendant who was his employer vicariously liable. The trial proceeded on consent from both parties that there was a 10% contribution of the plaintiff in the accident. The plaintiff was injured extensively and even had to be referred to Dubai for treatment by his neurosurgeon. However he did not suffer paralysis as was noted by the court. Te doctor testifying for the plaintiff claimed that the accident had reduced the plaintiff to a cabbage and a great liability and would thus not be able to do meaningful work all his life. The plaintiff argued that that before the accident, which occurred when he was in form two, the plaintiff was a B student, but ended up with a C- thus curtailing his dream of becoming a lawyer. The advocate for the plaintiff then computed a figure of Kshs. 150,000 per annum for a period of 30 years being a figure for loss of earnings now that the accident clearly hindered him from achieving his dream of becoming a lawyer. The court took cognizance of the fact that the veracity of the medical evidence tendered for the plaintiff was questionable. For instance the claim that the plaintiff had become a cabbage was clearly false as noted by his conduct in court- especially the fact that he was able to follow proceedings and respond accordingly. As doctor had also claimed that the plaintiffs right hand had become useless, but on cross examination the plaintiff testified that it was merely weak. The court also pointed out that no evidence was tendered to support the view that the plaintiff had actually aspired to become a lawyer, and that the matter of determining how much he would earn was quite speculative. No evidence was tendered to show that the plaintiffs performance declined as a result of the accident. The defendants argued that the sum being sought was

39

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

astronomical. The ultimate breakdown of the plaintiffs claim, amounting to Kshs. 78,268984/75 for compensation was as follows: Total special Damages. 4,268,984/75 Add General Damages for loss of earning For the rest of his life Kshs.

Kshs.54,000,000/= Add General Damages for loss of use of his limbs, Hand and brain

Kshs.20,000,000/= Grand Kshs.78,268,984/75 The court finally awarded a figure of Kshs. 4,545,450, broken down as follows: Pain and .Kshs.2,500,000/= Loss of Future Suffering Total

EarningKshs.1,000,000/= Special DamagesKshs.1,550,500/= TotalKshs.5,050,50 0/= Less 505,050/= 10% Contribution..Kshs.

40

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

TOTAL DUEKshs.4,545,450/= The court did manage to tone down the award, but the mischief in the plaintiffs advocate making such a huge claim is evident. The re is also the reality that in awarding compensation the court had to come up with a bargained sum. The high claim made may thus have had some impact on the judgment. 3.4.2DR. PAUL MACHARIA NDIRANGU v V.K. PATTNI & another [2010] eKLR This matter appeared before R. N. Sitati, sitting at the High Court in Nairobi. In this case the plaintiff, a medical doctor, alleged that he was walking along Ronald Ngala Street in Nairobi when he was hit by a vehicle belonging to the 1st defendant but driven by the second defendant. The court apportioned liability as 30% on the plaintiff and 70 % on the defendant. The plaintiff claimed that as a result of the accident he sustained fractures on his knee which he claims caused to undergo a knee surgery, and brought expert medical evidence claiming that he would need to undergo further surgery in the future. The plaintiff also claimed that he suffered high blood pressure as a result of the accident. He alleged that he was forced to close down his clinic because of the fractured knee and thus his earnings were affected. A breakdown of the compensation claimed, which amounted to Kshs. 18,000,940 by the plaintiff is as follows: General damages for pain, suffering and Loss of amenities .. Kshs. 1,000,000.00

Loss of earnings Kshs. 825,000.00 General damages for loss of future earnings Kshs.14,222,720.00

41

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012

Cost of future medical care Kshs. 766,500.00 Special damages . Kshs. 1,186,720.00 Total 18,000,940.00 The defense in this case brought expert medical evidence that challenged the veracity of the expert medical evidence tendered by the plaintiffs. The defense counsel also argued that the plaintiffs testimony was not true as the latter alleged that he became unconscious upon impact, yet the second defendant recalled that he was conscious and the medical report had no such indications of the plaintiff having been unconscious. The defense expert medical witness also contested that the plaintiff underwent surgery probably due to a complication that he already had and not only as a result of the accident. The courts final determination on the amount to award the plaintiff wasKshs.2,152,936.40, broken down as follows: General damages for pain, suffering and Suffering and loss of amenitiesKshs. 500,000.00 General damages for diminuted Diminished earning capacity..Kshs.2,000,000.00 Loss of earnings.Kshs. Special damages .Kshs. Cost of future medical care ....Kshs. 223,623.40 202,000.00 150,000.00 . Kshs.

Kshs.3,075,623.40 Less 922,687.02

42

30%

contribution

...........Kshs.

G34/2600/2008

GPR 410

2011/2012