Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Marxism and Religion

Uploaded by

ernestobulOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Marxism and Religion

Uploaded by

ernestobulCopyright:

Available Formats

Marxism and Religion Monday 6 June 2005, by Michael Lwy The Marxist view of religion has been greatly

over-simplified, typically identif ied with the well-worn refrain that it s the "opiate of the people." Michael Lwy ch allenges this misconception, and presents us with a much more nuanced view of Ma rxism and religion. Is religion still, as Marx and Engels saw it in the nineteenth century, a bulwar k of reaction, obscurantism and conservatism? To a large extent, the answer is y es. Their view still applies to many Catholic institutions, to the fundamentalis t currents of the main confessions (Christian, Jewish or Muslim), to most evange lical groups (and their expression in the so-called Electronic Church ) and to the majority of the new religious sects -some of which, such as the notorious Moon C hurch, are nothing but a skilful combination of financial manipulations, obscura ntist brain-washing and fanatical anti-communism. Liberation Theology However, the emergence of revolutionary Christianity and Liberation Theology in Latin America (and elsewhere) opens a new historical chapter and raises exciting new questions which cannot be answered without a renewal of the Marxist analysi s of religion, the subject of this article. The well-known phrase that religion is the "opiate of the people" is considered as the quintessence of the Marxist conception of the religious phenomenon by mos t of its supporters and its opponents. How far is this an accurate viewpoint? JPEG - 17.3 kb First of all, one should emphasize that this statement is not at all specificall y Marxist. The same phrase can be found, in various contexts, in the writings of German philosophers Kant, Herder, Feuerbach, Bruno Bauer, Moses Hess and Heinri ch Heine. For instance, in his essay on Ludwig Brne (1840), Heine already uses it -in a rather positive (although ironical) way: "Welcome be a religion that pours into the bitter chalice of the suffering human species some sweet, soporific dr ops of spiritual opium, some drops of love, hope and faith." Moses Hess, in his essays published in Switzerland in 1843, takes a more critica l (but still ambiguous) stand: "Religion can make bearable...the unhappy conscio usness of serfdom...in the same way as opium is of good help in painful diseases ." Hegel The expression appeared shortly afterwards in Marx s article on the German philoso pher Hegel s Philosophy of Right (1844). An attentive reading of the paragraph whe re this phrase appears, reveals that it is more qualified and less one-sided tha n usually believed. Although obviously critical of religion, Marx takes into acc ount the dual character of the phenomenon: "Religious distress is at the same ti me the expression of real distress and the protest against real distress. Religi on is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, just a s it is the spirit of an unspiritual situation. It is the opiate of the people." If one reads the whole essay, it appears clearly that Marx s viewpoint owes more t o left neo-Hegelianism, which saw religion as the alienation of the human essenc e, than to Enlightenment philosophy, which simply denounced it as a clerical con spiracy. In fact when Marx wrote the above passage he was still a disciple of Fe uerbach, and a neo-Hegelian. His analysis of religion was therefore "pre-Marxist ," without any class reference, and rather ahistorical. But it had a dialectical

quality, grasping the contradictory character of the religious "distress": both a legitimation of existing conditions and a protest against it. It was only later, particularly in The German Ideology (1846), that the proper M arxist study of religion as a social and historical reality began. The key eleme nt of this new method for the analysis of religion is to approach it as one of t he many forms of ideology - i.e. of the spiritual production of a people, of the production of ideas, representations and consciousness, necessarily conditioned by material production and the corresponding social relations. Although he uses from time to time the concept of "reflection" - which will lead several generations of Marxists into a sterile side-track - the key idea of the book is the need to explain the genesis and development of the various forms of consciousness (religion, ethics, philosophy, etc) by the social relations, "by which means, of course, the whole thing can be depicted in its totality (and the refore, too, the reciprocal action of these various sides on one another)." After writing, with Engels, The German Ideology, Marx paid very little attention to religion as such, i.e. as a specific cultural/ideological universe of meanin g. One can find, however, in the first volume of Capital, some interesting metho dological remarks; for instance, the well-known footnote where he answers to the argument according to which the importance of politics in the Ancient times, an d of religion in the Middle-Age reveal the inadequacy of the materialist interpr etation of history: "Neither could the Middle-Age live from Catholicism, nor Ant iquity from politics. The respective economic conditions explain, in fact, why C atholicism there and politics here played the dominant role." Marx will never bother to provide the economic reasons for the importance of med ieval religion, but this passage is quite important, because it acknowledges tha t, under certain historical circumstances, religion can indeed play a decisive r ole in the life of a society. In spite of his general lack of interest in religion, Marx paid attention to the relationship between Protestantism and capitalism. Several passages in Capital make reference to the contribution of Protestantism to the early emergence of ca pitalism-for instance by stimulating the expropriation of Church property and co mmunal pastures. Protestantism In the Grundrisse he makes - half a century before German sociologist Max Weber s famous essay The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism the following ill uminating comment on the intimate association between Protestantism and capitali sm: "The cult of money has its asceticism, its self-denial, its self-sacrifice-e conomy and frugality, contempt for mundane, temporal and fleeting pleasures; the chase after the eternal treasure. Hence the connection between English Puritani sm or Dutch Protestantism and money-making." The parallel (but not identity!) wi th Weber s thesis is astonishing - the more so since Weber could not have read thi s passage (the Grundrisse was published for the first time in 1940). On the other hand, Marx often referred to capitalism as a "religion of daily lif e" based on the fetishism of commodities. He described capital as "a Moloch that requires the whole world as a due sacrifice," and capitalist progress as a "mon strous pagan god, that only wanted to drink nectar in the skulls of the dead." His critique of political economy is peppered with frequent references to idolat ry: Baal, Moloch, Mammon, the Golden Calf and, of course, the concept of "fetish " itself. But this language has rather a metaphorical than a substantial meaning in terms of the sociology of religion.

Engels Engels displayed a much greater interest than Marx in religious phenomena and th eir historic role. Engels main contribution to the Marxist study of religions is his analysis of the relationship of religious representations to class struggle. Over and beyond the philosophical polemic of "materialism against idealism" he was interested in understanding and explaining concrete social and historical fo rms of religion. Christianity no longer appeared (like in Feuerbach) as a timele ss "essence", but as a cultural system undergoing transformations in different h istorical periods: first as a religion of the slaves, later as the state ideolog y of the Roman Empire, then tailored to feudal hierarchy and finally adapted to bourgeois society. It thus appears as a symbolic space fought over by antagonist ic social forces-for instance, in the sixteenth century, feudal theology, bourge ois Protestantism and plebeian heresies. Occasionally his analysis slips towards a narrowly utilitarian, instrumental int erpretation of religious movements: "each of the different classes uses its own appropriate religion... and it makes little difference whether these gentlemen b elieve in their respective religions or not." JPEG - 12.5 kb Salvadorean marchers carry banner of Archbishop Oscar Romero, assassinated by th e death squads, San Salvador 1980 Engels seems to find nothing but the religious disguise of class interests in the different forms of belief. However, thanks to his class-struggle method, he real ized-unlike the Enlightenment philosophers - that the clergy was not a socially homogeneous body: in certain historical conjunctures, it divided itself accordin g to its class composition. Thus during the Reformation, we have on the one side the high clergy, the feudal summit of the hierarchy, and on the other, the lowe r clergy, which supplied the ideologues of the Reformation and of the revolution ary peasant movement. While being a materialist, an atheist and an irreconcilable enemy of religion, E ngels nevertheless grasped, like the young Marx, the dual character of the pheno menon: its role in legitimating established order, but also, according to social circumstances, its critical, protesting and even revolutionary role. Furthermor e, most of the concrete studies he wrote concerned the rebellious forms of relig ion. Primitive Christianity First of all he was interested in primitive Christianity, which he defined as th e religion of the poor, the banished, the damned, the persecuted and oppressed. The first Christians came from the lowest levels of society: slaves, free people who had been deprived of their rights and small peasants who were crippled by d ebts. He even went so far as to draw an astonishing parallel between this primitive Ch ristianity and modern socialism: a) the two great movements are not the creation of leaders and prophets-although prophets are never in short supply in either o f them-but are mass movements; b) both are movements of the oppressed, suffering persecution, their members are proscribed and hunted down by the ruling authori ties; c) both preach an imminent liberation from slavery and misery. To embellish his comparison Engels, somewhat provocatively, quoted a saying of t he French historian Renan: "If you want to get an idea of what the first Christi an communities where like, take a look at a local branch of the International Wo rkingmen s Association" (the multi-national network of working-class organizations formed in 1864, also known as the First International).

According to Engels, the parallel between socialism and early Christianity is pr esent in all movements that dream, throughout the centuries, to restore the prim itive Christian religion-from the Taborites of John Zizka and the anabaptists of Thomas Mnzer to (after 1830) the French revolutionary com-munists and the partis ans of the German utopian com-munist Wilhelm Weitling. There remains, however, i n the eyes of Engels, an essential difference between the two movements: the pri mitive Christians transposed deliverance to the hereafter whereas socialism plac es it in this world. Thomas Mnzer But is this difference as clear-cut as it appears at first sight? In his study o f the great peasant wars in Germany it seems to become blurred: Thomas Mnzer, the theologian and leader of the revolutionary peasants and heretic (anabaptist) pl ebeians of the 16th century, wanted the immediate establishment on earth of the Kingdom of God, the millenarian Kingdom of the prophets. According to Engels, th e Kingdom of God for Mnzer was a society without class differences, private prope rty and state authority independent of, or foreign to, the members of that socie ty. However, Engels was still tempted to reduce religion to a stratagem: he spok e of Mnzer s Christian "phraseology" and his biblical "cloak". The specifically rel igious dimension of Mnzerian millenarianism, its spiritual and moral force, its a uthentically experienced mystical depth, seem to have eluded him. Engels does not hide his admiration for the German Chiliastic prophet, whose ide as he describes as "quasi-communist" and "religious revolutionary": they were le ss a synthesis of the plebeian demands from those times than "a brilliant antici pation" of future proletarian emancipatory aims. This anticipatory and utopian d imension of religion-not to be explained in terms of the "reflection theory" -is not further explored by Engels but is intensely and richly worked out (as we sh all see later) by Ernst Bloch. The last revolutionary movement that was waged under the banner of religion was, according to Engels, the English Puritan movement of the 17th century. If relig ion, and not materialism, furnished the ideology of this revolution, it is becau se of the politically reactionary nature of this philosophy in England, represen ted by Hobbes and other partisans of royal absolutism. In contrast to this conse rvative materialism and deism, the Protestant sects gave to the war against the Stuart royalty its religious banner and its fighters. This analysis is quite interesting: breaking with the linear vision of history i nherited from the Enlighten-ment, Engels acknowledges that the struggle between materialism and religion does not necessarily correspond to the war between revo lution and counter-revolution, progress and regression, liberty and despotism, o ppressed and ruling classes. In this precise case, the relation is exactly the o pposite one: revolutionary religion against absolutist materialism. European Labour Movement Engels was convinced that since the French Revolution, religion could no more fu nction as a revolutionary ideology, and he was surprised when French and German communists such as Cabet or Weitling would claim that "Christianity is Communism ." He could not predict liberation theology, but, thanks to his analysis of reli gious phenomena from the viewpoint of class struggle, he brought out the protest potential of religion and opened the way for a new approach-distinct both from Enlightenment philosophy (religion as a clerical conspiracy) and from German neo -Hegelianism (religion as alienated human essence)-to the relationship between r eligion and society. Many Marxists in the European labour movement were radically hostile to religion but believed that the atheistic battle against religious ideology must be subor

dinated to the concrete necessities of the class struggle, which demands unity b etween workers who believe in God and those who do not. Lenin himself, who very often denounced religion as a "mystical fog", insisted in his article Socialism and Religion (1905) that atheism should not be part of the party s programme becau se "unity in the really revolutionary struggle of the oppressed class for creati on of a paradise on earth is more important to us than unity of proletarian opin ion on paradise in heaven." Rosa Luxemburg shared this strategy, but she developed a different and original approach. Although a staunch atheist herself, she attacked in her writings less religion as such than the reactionary policy of the Church in the name of its ow n tradition. In an essay written in 1905 ( Church and Socialism ) she claimed that m odern socialists are more faithful to the original principles of Christianity th an the conservative clergy of today. Since the socialists struggle for a social order of equality, freedom and fraternity, the priests, if they honestly wanted to implement in the life of humanity the Christian principle "love thy neighbour as thyself", should welcome the socialist movement. When the clergy support the rich, and those who exploit and oppress the poor, they are in explicit contradi ction with Christian teachings: they do serve not Christ but the Golden Calf. The first apostles of Christianity were passionate communists and the Fathers of the Church (like Basil the Great and John Chrysostom) denounced social injustic e. Today this cause is taken up by the socialist movement which brings to the po or the Gospel of fraternity and equality, and calls on the people to establish o n earth the Kingdom of freedom and neighbour-love. Instead of waging a philosoph ical battle in the name of materialism, Rosa Luxemburg tried to rescue the socia l dimension of the Christian tradition for the labour movement. Ernst Bloch Ernst Bloch is the first Marxist author who radically changed the theoretical fr amework - without abandoning the Marxist and revolutionary perspective. In a sim ilar way to Engels, he distinguished two socially opposed currents: on one side the theocratic religion of the official churches, the opiate of the people, a my stifying apparatus at the service of the powerful; on the other the underground, subversive and heretical religion of the Albigensians, the Hussites, Joachim de Flore, Thomas Mnzer, Franz von Baader, Wilhelm Weitling and Leo Tolstoy. However , unlike Engels, Bloch refused to see religion uniquely as a "cloak" of class in terests: he explicitly criticized this conception. In its protest and rebellious forms religion is one of the most significant forms of utopian consciousness, o ne of the richest expressions of the Principle of Hope. Basing himself on these philosophical presuppositions, Bloch develops a heterodo x and iconoclastic interpretation of the Bible-both the Old and the New Testamen ts-drawing out the Biblia pauperum (bible of the poor) which denounces the Phara ohs and calls on each and everyone to choose either Caesar or Christ. A religious atheist-according to him only an atheist can be a good Christian and vice-versa-and a theologian of the revolution, Bloch not only produced a Marxis t reading of millenarianism (following Engels) but also-and this was new-a mille narian interpretation of Marxism, through which the socialist struggle for the K ingdom of Freedom is perceived as the direct heir of the eschatological and coll ectivist heresies of the past. Of course Bloch, like the young Marx of the famous 1844 quotation, recognized th e dual character of the religious phenomenon, its oppressive aspect as well as i ts potential for revolt. The first requires the use of what he calls the cold str eam of Marxism : the relentless materialist analysis of ideologies, idols and idol atries. The second one however requires the warm stream of Marxism, seeking to res cue religion s utopian cultural surplus, its critical and anticipatory force. Beyo

nd any dialogue, Bloch dreamt of an authentic union between Christianity and revol ution, like the one which came into being during the Peasant Wars of the 16th ce ntury. Frankfurt School Bloch s views were to a certain extent shared by members of the German radical sch olars known as the Frankfurt School. Max Horkheimer considered that "religion is the record of the wishes, nostalgias and indictments of countless generations." Erich Fromm, in his book The Dogma of Christ (1930), used Marxism and psychoana lysis to illuminate the Messianic, plebeian, egalitarian and anti-authoritarian essence of primitive Christianity. And the writer Walter Benjamin tried to combi ne, in a unique and original synthesis, theology and Marxism, Jewish Messianism and historical materialism, class struggle and redemption. Lucien Goldmann s work The Hidden God (1955) is another path-breaking attempt at r enewing the Marxist study of religion. Although of a very different inspiration than Bloch, he was also interested in redeeming the moral and human value of rel igious tradition. The most surprising and original part of his book is the attem pt to compare-without assimilating one to another-religious faith and Marxist fa ith: both have in common the refusal of pure individualism (rationalist or empir icist) and the belief in trans-individual values: God for religion, the human co mmunity for socialism. In both cases the faith is based on a wager - the wager on the existence of God and the Marxist wager on the liberation of humanity-that presupposes risk, the d anger of failure and the hope of success. Both imply some fundamental belief whi ch is not demonstrable on the exclusive level of factual judgements. What separates them is of course the suprahistorical character of religious tran scendence: "The Marxist faith is a faith in the historical future that human bei ngs themselves make, or rather that we must make by our activity, a wager in the s uccess of our actions; the transcendence that is the object of this faith is nei ther supernatural nor transhistorical, but supra-individual, nothing more but al so nothing less." Without wanting in any way to "Christianize Marxism" Lucien Go ldmann introduced, thanks to the concept of faith, a new way of looking at the c onflictual relationship between religious belief and Marxist atheism. Marx and Engels thought religion s subversive role was a thing of the past, which no longer had any significance in the epoch of modern class struggle. This forec ast was more or less historically confirmed for a century - with a few important exceptions (particularly in France): the Christian socialists of the 1930s, the worker priests of the 1940s, the left-wing of the Christian unions in the 1950s , etc. But to understand what has been happening for the last thirty years in Latin Ame rica (and to a lesser extent also in other continents) around the issue of Liber ation Theology we need to integrate into our analysis the insights of Bloch and Goldmann on the utopian potential of the Judeo-Christian tradition. Oppression of women and religious doctrine What is sorely lacking in these "classical" Marxist discussions on religion is a discussion of the implications of religious doctrines and practices for women. Patriarchy, unequal treatment of women, and the denial of reproductive rights pr evail among the main religious denominations - particularly Judaism, Christianit y and Islam - and take extremely oppressive forms among fundamentalist currents. In fact, one of the key criteria for judging the progressive or regressive chara cter of religious movements is their attitude towards women, and particularly on

their right to control their own bodies: divorce, contraception, abortion. A re newal of Marxist reflection on religion in the twenty-first century requires us to put the issue of women s rights at the center of the argument.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Report of SWP's Disputes CommitteeDocument22 pagesReport of SWP's Disputes CommitteeernestobulNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Genocide in The Sculpture Garden and Talking Back To Settler ColonialismDocument27 pagesGenocide in The Sculpture Garden and Talking Back To Settler ColonialismKelly YoungNo ratings yet

- Lars Lih and Lenin's April ThesesDocument4 pagesLars Lih and Lenin's April ThesesernestobulNo ratings yet

- Capitalism and The StateDocument4 pagesCapitalism and The StateernestobulNo ratings yet

- What Popular Unity Can DoDocument2 pagesWhat Popular Unity Can DoernestobulNo ratings yet

- JappeDocument7 pagesJappeernestobulNo ratings yet

- Kuhn Henryk Grossman and The Recovery of Marxism HM 13-3-2005Document44 pagesKuhn Henryk Grossman and The Recovery of Marxism HM 13-3-2005ernestobul100% (1)

- The Us Rate of ProfitDocument5 pagesThe Us Rate of ProfiternestobulNo ratings yet

- New Age MarxismDocument10 pagesNew Age MarxismernestobulNo ratings yet

- Tapering and The Emerging MarketsDocument2 pagesTapering and The Emerging MarketsernestobulNo ratings yet

- A Response To Andrew KlimanDocument7 pagesA Response To Andrew KlimanernestobulNo ratings yet

- The Current Financial CrisisDocument6 pagesThe Current Financial CrisisernestobulNo ratings yet

- Chronological TableDocument4 pagesChronological TableernestobulNo ratings yet

- Smith, Hegel, Economics, and Marxs CapitalDocument12 pagesSmith, Hegel, Economics, and Marxs CapitalernestobulNo ratings yet

- Why Are Bankers Killing ThemselvesDocument2 pagesWhy Are Bankers Killing ThemselvesernestobulNo ratings yet

- Tapering and The Emerging MarketsDocument2 pagesTapering and The Emerging MarketsernestobulNo ratings yet

- The Current Financial CrisisDocument6 pagesThe Current Financial CrisisernestobulNo ratings yet

- Desarrollo y ambivalencias de la teoría económica de MarxDocument16 pagesDesarrollo y ambivalencias de la teoría económica de MarxPino AlessandriNo ratings yet

- Who Is John GaltDocument2 pagesWho Is John GalternestobulNo ratings yet

- Barrett BrownDocument14 pagesBarrett BrownernestobulNo ratings yet

- Process Physics: From Information Theory to Quantum Space and MatterDocument110 pagesProcess Physics: From Information Theory to Quantum Space and Matterernestobul100% (1)

- Interview With Jasmine CurcioDocument6 pagesInterview With Jasmine CurcioernestobulNo ratings yet

- China's New MilitancyDocument34 pagesChina's New MilitancyernestobulNo ratings yet

- The Real of ViolenceDocument5 pagesThe Real of ViolenceernestobulNo ratings yet

- The Real of ViolenceDocument5 pagesThe Real of ViolenceernestobulNo ratings yet

- The Dialectics of Secularization: Habermas and Ratzinger Debate Religious and Secular ReasonDocument3 pagesThe Dialectics of Secularization: Habermas and Ratzinger Debate Religious and Secular ReasonernestobulNo ratings yet

- Gov't Knows BestDocument3 pagesGov't Knows BesternestobulNo ratings yet

- Left Melancholy and Whitlam's GhostsDocument4 pagesLeft Melancholy and Whitlam's GhostsernestobulNo ratings yet

- Jodi DeanDocument7 pagesJodi DeanernestobulNo ratings yet

- Communism and Left MelancholyDocument2 pagesCommunism and Left MelancholyernestobulNo ratings yet

- (Advances in Political Science) David M. Olson, Michael L. Mezey - Legislatures in The Policy Process - The Dilemmas of Economic Policy - Cambridge University Press (1991)Document244 pages(Advances in Political Science) David M. Olson, Michael L. Mezey - Legislatures in The Policy Process - The Dilemmas of Economic Policy - Cambridge University Press (1991)Hendix GorrixeNo ratings yet

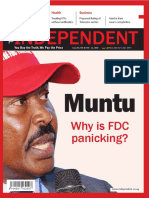

- THE INDEPENDENT Issue 541Document44 pagesTHE INDEPENDENT Issue 541The Independent MagazineNo ratings yet

- Assignment - Professional EthicsDocument5 pagesAssignment - Professional EthicsAboubakr SoultanNo ratings yet

- Writing BillsDocument2 pagesWriting BillsKye GarciaNo ratings yet

- dhML4HRSEei8FQ6TnIKJEA C1-Assessment-WorkbookDocument207 pagesdhML4HRSEei8FQ6TnIKJEA C1-Assessment-WorkbookThalia RamirezNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Contract LawDocument6 pagesIntroduction To Contract LawTsholofeloNo ratings yet

- Masturbation Atonal World ZizekDocument7 pagesMasturbation Atonal World ZizekSoren EvinsonNo ratings yet

- Why Firefighters Die - 2011 September - City Limits MagazineDocument33 pagesWhy Firefighters Die - 2011 September - City Limits MagazineCity Limits (New York)100% (1)

- Macaulay's linguistic imperialism lives onDocument16 pagesMacaulay's linguistic imperialism lives onsreenathpnrNo ratings yet

- Multilateralism Vs RegionalismDocument24 pagesMultilateralism Vs RegionalismRon MadrigalNo ratings yet

- West Philippine SeaDocument14 pagesWest Philippine Seaviva_33100% (2)

- Kenya Law Internal Launch: Issue 22, July - September 2013Document248 pagesKenya Law Internal Launch: Issue 22, July - September 2013ohmslaw_Arigi100% (1)

- 10 Barnachea vs. CADocument2 pages10 Barnachea vs. CAElieNo ratings yet

- Providing Culturally Appropriate Care: A Literature ReviewDocument9 pagesProviding Culturally Appropriate Care: A Literature ReviewLynette Pearce100% (1)

- Module 2. Gender & Society) - Elec 212Document6 pagesModule 2. Gender & Society) - Elec 212Maritoni MedallaNo ratings yet

- 13 - Wwii 1937-1945Document34 pages13 - Wwii 1937-1945airfix1999100% (1)

- Sept 8Document8 pagesSept 8thestudentageNo ratings yet

- Jerome PPT Revamp MabiniDocument48 pagesJerome PPT Revamp Mabinijeromealteche07No ratings yet

- Mil Reflection PaperDocument2 pagesMil Reflection PaperCamelo Plaza PalingNo ratings yet

- Sociology ProjectDocument20 pagesSociology ProjectBhanupratap Singh Shekhawat0% (1)

- XAT Essay Writing TipsDocument17 pagesXAT Essay Writing TipsShameer PhyNo ratings yet

- 1 QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQDocument8 pages1 QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQJeremy TatskiNo ratings yet

- Quilt of A Country Worksheet-QuestionsDocument2 pagesQuilt of A Country Worksheet-QuestionsPanther / بانثرNo ratings yet

- Presidential Democracy in America Toward The Homogenized RegimeDocument16 pagesPresidential Democracy in America Toward The Homogenized RegimeAndreea PopescuNo ratings yet

- 80-Madeleine HandajiDocument85 pages80-Madeleine Handajimohamed hamdanNo ratings yet

- PIL NotesDocument19 pagesPIL NotesGoldie-goldAyomaNo ratings yet

- SGLGB Form 1 Barangay ProfileDocument3 pagesSGLGB Form 1 Barangay ProfileDhariust Jacob Adriano CoronelNo ratings yet

- LANGUAGE, AGE, GENDER AND ETHNICITYDocument16 pagesLANGUAGE, AGE, GENDER AND ETHNICITYBI2-0620 Nur Nabilah Husna binti Mohd AsriNo ratings yet

- WTO PresentationDocument22 pagesWTO PresentationNaveen Kumar JvvNo ratings yet